Abstract

Objectives: There is limited research on the meaning in life among Chinese elders. This study aims to examine the association among functional disabilities, meaning in life, social network, and quality of life in community-dwelling Chinese elders with low socioeconomic status. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was used to collect data from 339 poor community-dwelling Chinese elders aged 60 and above. Results: The results showed that meaning in life and social network were significantly related to quality of life. Moreover, social network was a mediator to the relationship between functional disability and quality of life, and meaning in life was a partial mediator to the relationship between social network and quality of life. Conclusion: Workshops should be organized by the elderly service providers for Chinese elders facing deterioration in health and activity levels to learn to live intentionally and purposefully. A social network among elders should also be fostered in the community.

Keywords: meaning in life, social network, quality of life, community-dwelling, Chinese elders

Meaning in Life for the Elders

The sense of meaning and purpose in life are important components of quality of life (Sarvimäki & Stenbock-Hult, 2000). There are two main dimensions in meaning in life: the search for meaning and the presence of meaning (Thomas, Burton, Griffin, & Fitzpatrick, 2010). The former refers to the degree of a person’s engagement in searching for meaning in life while the latter refers to the degree of individual perception toward ones’ life as significant and meaningful. Individuals who have meaningful interpretations of life with the presence of life schemes and goals tend to have better well-being (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). Such people are sometimes able to see that they have grown in the face of adversity and then became associated with better mental health (Krause, 2004). Therefore, meaning in life is one of the coping resources (Krause, 2007). The above studies focused on Western societies.

Asian societies that emphasize harmony may produce different effects of meaning in life on individual well-being. One study found that searching for meaning is positively related to the presence of meaning and well-being in Japan while it is negatively related to the presence of meaning and well-being in the United States (Thomas et al., 2010). Collectivist cultures place high values on effort and the process of self-improvement that endorse high levels of the search for meaning. People who socialize in such cultures may expect that searching for and the presence of desirable outcomes will go hand-in-hand (Thomas et al., 2010). That may be the reason why both the presence of meaning and search for meaning have the same effect on individual well-being in Asian societies. Meaning in life plays an important role in enhancing the subjective well-being of community-dwelling elders in Korea (Ju, Shin, Kim, Hyun, & Park, 2013). It partially mediates the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being. A study of Chinese secondary students in Hong Kong also revealed that meaning in life is related to psychological well-being in terms of psychological disturbances, anxiety, and depression (Shek, 1992). In Chinese culture, rich meaning of life is related to a sense of self-responsibility toward ones’ well-being as well as a responsibility to serve the society and other people without any rewards (H. Zhang, Shan, & Jiang, 2014). Elders with functional disabilities may deteriorate their sense of meaning in life because of their perception that they are unable to perform their duties as usual. This study focuses upon the role of meaning in life for the community-dwelling Chinese elders with low socioeconomic status.

Previous studies suggest that meaning in life is important to elder people’s well-being. Meaning in life was found to be an important coping resource to the physical and psychological well-being of nursing home elders (Haugan, 2014). While reestablishment and the search for meaning in life is crucial for elders who are in the last stage of life, which emphasizes integrity, elders with major regrets and who fail to achieve integrity tend to fall into despair, while a strong sense of meaning can help people in late life to cope with stressful life experience, illness, and death anxiety (Dwyer, Nordenfelt, & Ternestedt, 2008; Thomas et al., 2010). The strong sense of meaning in life offsets the negative effects of lifetime trauma, such as loss of the partner, on depression among elders (Krause, 2007); and it can increase optimistic expectation of their future (Ju et al., 2013). All these show that meaning in life is vital to enhance the well-being of elders.

The role of meaning in life seems to take the same effect for Chinese elders. Holding a positive meaning of illness is consistent with the traditional Chinese values that emphasize happiness lying in contentment and letting nature take its course (H. Zhang et al., 2014). Value of life is an important predictor of the quality of life among Chinese patients with advanced cancer (Lau, Mok, Lai, & Chung, 2013). The buffering role of meaning in life is confirmed for the effect of stress from life trauma on the well-being as well as the influence of physical function on well-being. However, the above studies focused upon some specific groups of Chinese elders, such as patients, stroke survivors, or nursing home residents. Elders with middle and high socioeconomic status can employ domestic servants or professional helpers to assist them to handle the household chores. Lacking financial resource may cause those with low socioeconomic status to encounter more difficulties in their daily living. Therefore, this study aims to examine whether the positive effect of meaning in life exists for the poor community-dwelling elders in the Chinese society who face financial stress and low levels of functional status.

Functional Capacity and Quality of Life

Functional limitations are likely to be reported by individuals of old age. A 6.9% prevalence rate of functional limitations among Hong Kong community-dwelling Chinese elders aged 60 years old and above was reported (Census and Statistics Department, 2009). Functional capacity in daily activities is one of the factors that explained life satisfaction and quality of life of the elders (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008; Pan, Song, Lee, & Kwok, 2008). Declining activity level and engagement in physical activity are related to lower quality of life among elders (Brovold, Skelton, Sylliaas, Mowe, & Bergland, 2014). Decrease in activity level will decrease exercise self-efficacy and physical self-worth and, in turn, hinders life satisfaction (Phillips, Wójcicki, & McAuley, 2013). Consistent with other Western studies, functional capacities are related to quality of life and life satisfaction among Chinese elders (Chan et al., 2009; Lau et al., 2013). Chinese elders have a similar conception of the quality of life as the Westerners. Having good health and being able to interact with people outside the home, as well as participating in community activities, are considered as important to the quality of life (Li, Chi, & Xu, 2013). Those factors are associated with the functional capacities of the elders. Therefore, it is anticipated that Chinese elders who have greater functional limitations tend to have lower levels of quality of life.

Functional Abilities and Meaning in Life

The sense of meaning and purpose in life is predicted by functional capacity (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008). The level of independence in activities of daily living is positively related with meaning in life (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008). Maintaining physical function and continuing engagement in social life are important elements of successful aging (Dwyer et al., 2008). Personal suffering is one of the main determinants of the reduction of meaning in life (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008). Meaningful life can only be achieved when people can maintain a role or attain a goal in life events (Jafary, Farahbakhsh, Shafiabadi, & Delavar, 2011). Unable to execute or comply with key social role expectations erodes the sense of meaning in life (Krause, 2004). Problems in performing the role make the elders feel that their actions are unable to fit into the wider social order and forces them to view that their goals may be difficult to achieve. Functional disabilities are associated with personal dignity in Chinese culture (Lau et al., 2013). The Chinese cultural values that emphasize personal contribution to the family and strong work ethic make Chinese people unwilling to be dependent on family and become a burden (Kim, Warren, Madill, & Hadley, 1999). However, lack of functional independence hinders elders from participating in meaningful activities and leads them to question the values that they endorsed and creates a sense of suffering. This study anticipates that meaning in life mediates the effects of functional capacities on quality of life.

Social Network, Meaning in Life, and Quality of Life

Social network is important to the elders, especially for those who have chronic illnesses. Psychological support and the quality of their social network have been found to benefit the elderly patients (Ma et al., 2015). Consistent with other Western studies, social network, family support, and quality of social support are related to life satisfaction among Hong Kong Chinese elders (Sun, Liu, Webber, & Shi, 2017). The perceived support from children are predictors of the quality of life of older Chinese living alone in Hong Kong (Lee, 2005). Social network reduces the levels of loneliness, and, in turn, improves the quality of life among Chinese elders (Liu & Guo, 2007).

Social network is also related to meaning in life. One study found that meaning in life is a strong predictor and a mediator to the relationship of physical functioning and social networks with subjective well-being among Chinese elderly stroke survivors (Shao, Zhang, Lin, Shen, & Li, 2014). Maintaining social relationships generates the meaning in life, and it is a vital source of strength of life (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008). Family contacts provide meaning in life (Sarvimäki & Stenbock-Hult, 2000). The social network is a source of the sense of meaning for the patient. It helps patients with chronic illness to find new life purpose and establish their life goal (Shao et al., 2014). Having greater involvement in family, friends, and significant others strengthens the patients’ willingness to continue to live and foster their sense of purpose-in-life. The function of the social network on meaning in life can also apply to the elders. Emotional support from the social network helps the elders to restore their sense of meaning in life (Krause, 2004). Moreover, the renewal of successful role performance depends on the input and influence of significant others. Family members and close friends can remind the elder people of their past success and rebuild their sense of identity. These significant others may also help the elders to find a new sense of purpose by helping them to see that deterioration in their activities level is an inevitable part of life, and the difficulties encountered from aging are often a necessary prerequisite for personal growth (Krause, 2004). The above findings suggest that meaning in life is a mediator to the relationship between social network and quality of life.

Studies of Western and Chinese societies indicate that financial status is one of the main factors that directly influence quality of life of older people ( Y.Chen, Hicks, & While, 2013; T. Zhang et al., 2016). This study aims at exploring whether enhancing meaning in life can help such Chinese elders to improve their quality of life. Based on findings from previous studies on meaning in life, functional disability, and quality of life of the elders, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1: Functional disability, meaning in life, and social network are associated with quality of life.

Hypothesis 2: Meaning in life mediates the relationship between functional disability and quality of life; and it also mediates the relationship between social network and quality of life.

Method

Participants

Data for this study came from an original data set focused on the well-being of Chinese elders in Hong Kong. This study targets that part of the sample group who have low family income. Samples of 339 poor community-dwelling Chinese elders with a monthly family income below the 25 percentile of the nominal family income in Hong Kong (Census and Statistics Department, 2015) were used in the study. The sample consisted of 45.3% males and 54.7% females. Participants’ ages ranged from 60 to 95 years, with a mean (M) age of 76.19 and a standard deviation (SD) of 7.48. There were 40.7% of respondents aged between 60 and 74, 44.5% aged between 75 and 84, and 14.7% aged above 85 years old. The majority (72.6%) only had primary school education, and 21.4% had junior-secondary education. Most of the participants were clustered in the very low-income families, with 75.8% having a monthly family income below HKD5,000 (US$643) and 24.2% of families having a monthly income of HKD10,000 (US$1,286).

Indicators

Functional disability

The 8-item Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL; Lawton & Brody, 1969) was used to measure the functional disability of participants. The disability is defined as the loss of capability to perform at least one area of daily activity independently, such as food preparation and housekeeping. The total scores ranged from 0 to 8, with higher scores implying a higher level of functioning disability and dependence. In this study, the scale has a very good internal consistency reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of .824.

Social network

The Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS; Lubben & Gironda, 2004) was adopted to measure the social network of participants. The scale contains three subscales: family support (examples of scale items, “How many relatives do you see or hear from at least once a month?”), peer support (examples of scale items, “How many friends do you feel at ease with that you can talk about private matters?”), and support from significant others (examples of scale items, “Do you have someone available for you to talk to when you have an important decision to make?”). A higher total score indicates more social engagement. The scale has a good internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .793. The three subdomains, family support (Cronbach’s α = .752), peer support (Cronbach’s α = .852), and support from significant others (Cronbach’s α = .703) also have good internal consistency reliability.

Meaning in life

The 10-item Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger et al., 2006) was used in this study. The scale consists of 10 items with two dimensions (the presence of meaning and the search for meaning), and scores range between 10 and 70. Examples of scale items include statements such as, “I understand my life’s meaning” (the presence of meaning) and “I am searching for meaning in my life” (the search for meaning). The MLQ in this study has an excellent internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .921. The two subdomains, the presence of meaning (Cronbach’s α = .847) and the search for meaning (Cronbach’s α = .914), both have very good internal consistency reliability.

Quality of life

The quality of life was measured by three dimensions of the Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL; Bowling, 2009). The original scale has 8 dimensions and 35 items. The study used 23 items from 3 dimensions, the Life Satisfaction, Social Relationships, and Psychological and Emotional Well-Being, to reflect the quality of life of respondents. Scores range between 13 and 65. Examples of scale items include statements such as, “I enjoy my life overall,” “My family, friends or neighbours would help me if needed,” and “I take life as it comes and make the best of things.” This scale has an excellent internal consistency reliability in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .904. The three subdomains, life satisfaction (Cronbach’s α = .794), social relationships (Cronbach’s α = .840), and psychological and emotional well-being (Cronbach’s α = .744), also have good internal consistency reliability.

Procedure and Data Analysis Strategies

Data of the study came from a cross-sectional survey that was collected between February and April 2015. Ethical approval for this project was obtained from the university’s research ethics committee. Student helpers were recruited to conduct face-to-face interviews in streets near elderly centers, old urban areas, and public estates. Participants voluntarily participated in the survey with questionnaires, including the different variable indicators, and demographic information. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22, and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS), version 22, were used to analyze the data. First, ANOVA analyses were employed to compare the score of each variable among respondents from different backgrounds. Second, the associations between the key variables were reported. AMOS 22 was used to test the goodness of fit of a hypothesized structural equation model. Sobel tests were also conducted to examine the mediation effect of social network and meaning in life.

Results

The situation of the main participants of this study was compared with the group of 465 community-dwelling Chinese elders who are not from low-income families in the original data set. Results of the ANOVA analyses are in line with those of previous studies from Chinese and Western societies; that is, that people from low socioeconomic status have poor quality of life (Y. Chen et al., 2013; Lubetkin, Jia, Franks, & Gold, 2005). Chinese elders from low-income families as compared with people who are not from low-income families have a poor quality of life (M = 48.01, SD = 8.19; M = 51.05, SD = 7.51, F = 13.85, p < .001), narrower social network (M = 18.08, SD = 8.48; M = 23.14, SD = 8.71, F = 36.72, p < .001), and lower score in presence of meaning (M = 22.55, SD = 5.71; M = 24.05, SD = 6.22, F = 5.97, p = .02) and search for meaning (M = 20.19, SD = 5.84; M = 22.04, SD = 6.12, F = 8.99, p = .01).

ANOVA analyses were conducted to examine the association between background of respondents and the study variables. Table 1 indicates that older Chinese elders had a higher level of functional disability and lower score in search for meaning than the younger ones. Elders with higher educational attainment had a higher score in presence of meaning and search for meaning, a wider social network, and a higher level of quality of life than those with lower educational attainment. Moreover, females had a wider social network than male respondents.

Table 1.

Functional Disability, Presence of Meaning, Search for Meaning, Social Network, and Quality of Life Between Groups With Different Backgrounds.

| Background | Functional disability |

Presence of meaning |

Search for meaning |

Social network |

Quality of life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age | |||||

| 60-74 | 0.49 (1.37) | 23.02 (6.07) | 21.01 (5.84) | 18.58 (8.94) | 49.78 (7.62) |

| 75-84 | 0.58 (1.22) | 22.31 (5.52) | 19.96 (5.89) | 17.72 (7.97) | 47.43 (7.93) |

| 85 or above | 1.48 (2.12) | 21.91 (5.21) | 18.50 (5.36) | 17.80 (8.78) | 46.69 (10.07) |

| p < .01 | n.s. | p = .04 | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 0.77 (1.67) | 21.96 (5.63) | 19.59 (5.59) | 16.88 (8.72) | 47.30 (7.25) |

| Female | 0.59 (1.31) | 23.06 (5.76) | 20.69 (6.04) | 19.03 (8.17) | 48.60 (8.89) |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | p = .02 | n.s. | |

| Education | |||||

| Primary | 0.79 (1.56) | 21.88 (5.69) | 19.46 (5.86) | 17.06 (8.52) | 47.08 (8.02) |

| Lower Secondary | 0.46 (1.38) | 23.20 (5.46) | 21.27 (5.26) | 20.19 (8.03) | 49.85 (8.80) |

| Upper Secondary | 0.06 (0.24) | 27.09 (4.23) | 24.00 (5.52) | 22.68 (6.94) | 52.43 (5.46) |

| n.s. | p < .01 | p < .01 | p < .01 | p < .01 | |

Note. n.s. = not significant.

Table 2 presents the correlations among the study variables. As predicted, functional disability was inversely related to presence of meaning (r = –.11, p = .034), search for meaning (r = –.15, p < .01), and quality of life (r = –.19, p < .01). Quality of life was positively related to presence of meaning (r = .57, p < .001), search for meaning (r = .50, p < .001), and social network (r = .67, p < .001). Finally, social network was positively related to presence of meaning (r = .42, p < .001) and search for meaning (r = .39, p < .001).

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix for the Quality of Life and the Independent Measures (n = 366).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Quality of Life | — | 48.65 | 7.31 | ||||

| 2. Functional Disability | −.19** | — | 0.69 | 1.47 | |||

| 3. Presence of Meaning | .57*** | −.11* | — | 22.55 | 5.71 | ||

| 4. Search for Meaning | .50*** | −.15** | .72*** | — | 20.18 | 5.84 | |

| 5. Social Network | .67*** | −.25*** | .42*** | .39*** | — | 18.32 | 8.69 |

Note. Quality of Life = scores on the Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL); Functional Disability = scores on the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL); Presence of Meaning and Search for Meaning = scores on the two subdomains on Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ); Social Network = scores on the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS).

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Baron and Kenny (1986) suggested the use of a three-step procedure to test the mediating effect. In step 1, results in the correlation analysis suggest the elders’ functional disability as an independent variable was related with quality of life. In step 2, social network and meaning in life as mediators were significantly related with quality of life, as shown in Table 2.

In step 3, a structural equation model was developed to test the indirect effect of functional disability via social network and meaning in life. A path analysis was conducted to test the conceptual model. It is hypothesized that a higher functional disability level was related to a lower level of meaning in life and a lower level of quality of life. A higher level of social networks was related to a higher level of meaning in life and a higher level of quality of life. Moreover, a higher level of meaning in life was related to a higher level of quality of life.

The chi-square goodness of fit statistic, χ2(21) = 32.69, p < .001, failed to support the hypothesized model, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.11 was unacceptable. Because the conceptual model was not supported, model modifications were performed to identify a better fitting model. Utilizing the modification index, an updated model was established by removing the direct path from functional disability to meaning in life and the direct path from functional disability to quality of life, but adding a direct path from functional disability to social network. The revised model yielded a satisfied goodness of fit statistic, χ2(16) = 23.84, p = .093. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.98, the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) = 0.94, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.97, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.99 were all larger than 0.95 and close to 1, indicating that the modified model had a very good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). The RMSEA value was smaller than 0.05, which also indicated a close fit (Ho, 2006).

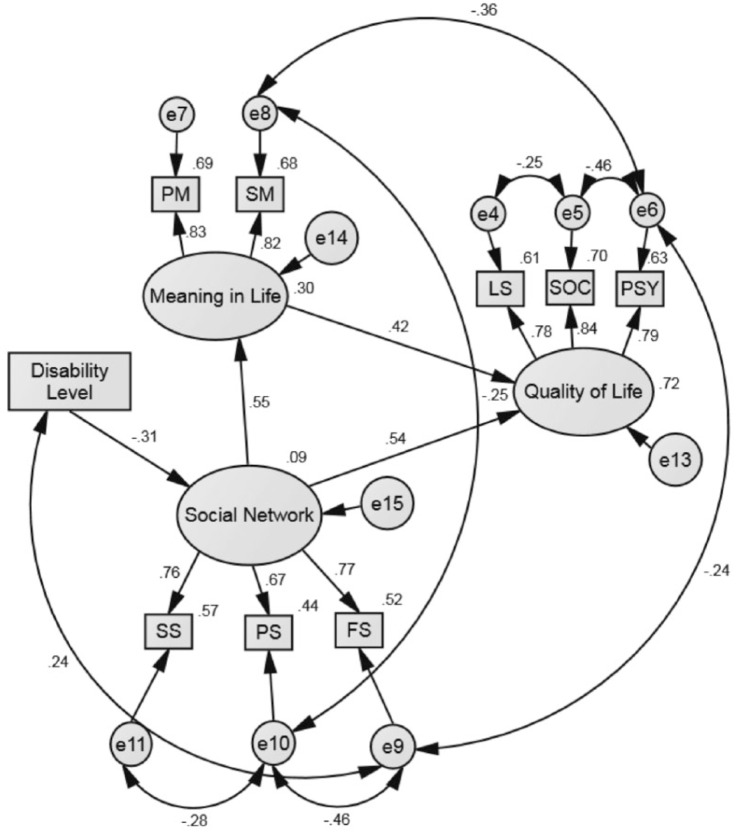

Figure 1 summarizes the path analysis results of the modified model, functional disability had a negative relationship with social network (β = –.31, p < .001). Moreover, social network had a positive relationship with meaning in life (β = .55, p < .001) and a positive relationship with quality of life (β = .54, p < .001). Finally, meaning in life had a positive relationship with quality of life (β = .42, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model of the relationship among functional disability, social network, meaning in life, and quality of life.

Note. PM = presence of meaning; SM = search for meaning; LS = life satisfaction; SOC = social relationships; PSY = psychological and emotional well-being; SS = support from significant others; PS = peer support; FS = family support.

The results of the structural equation model presented in Figure 1 show that meaning in life and social network were significantly related to quality of life, and functional disability was not directly related to it. Moreover, functional disability was not related with meaning in life directly but social network was directly related with it. These results indicate that social network was a mediator in the relationship between functional disability and quality of life, and meaning in life was a partial mediator in the relationship between social network and quality of life.

Sobel tests were used to examine the indirect effect of social network on quality of life via increasing meaning in life, and the indirect effect of functional disability on quality of life via lowering social network. Results showed that functional disability had an indirect effect on quality of life via lowering social network (t = −3.42, p < .001) and via lowering social network and decreasing meaning in life (t = 4.19, p < .001).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study confirms the relationship of quality of life with functional disabilities, social network, and meaning in life. The relationship among these variables has not been tested in previous studies in the Chinese context. Consistent with findings of previous studies, functional abilities is one of the predictors of quality of life among community-dwelling Chinese elders (Shao et al., 2014). Especially, previous studies have suggested that the disabilities in physical health have serious negative impact on the quality of life of Chinese elders with frailty and Chinese post-stroke patients (Lin et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2008). However, the effect of functional ability on quality of life is indirect. Improvement in physical conditions cannot guarantee the enhancement in subjective well-being. The study found that the quality of life fails to improve over time even though the functional status of the ex-stroke patient increases (Kim et al., 1999). Therefore, the subjective experiences rather than the objective physical conditions have more influence on the quality of life.

The research results did not support the direct association between functional capacity and meaning in life, as stated in previous studies (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008). This suggests that there are more important factors than physical disabilities associated with the meaning in life of Chinese elders. If Chinese elders can take care of themselves, without losing the ability of self-care and are being treated with dignity and receiving respect from family members and other people, they may not lose their sense of responsibility and self-maintenance. Children’s happiness, filial piety, the spirit of contentment, and endurance also help Chinese elders to maintain their meaning in life and happiness even when they experience deterioration in physical health (H. Zhang et al., 2014). Further study can be conducted to clarify the relationships among functional disabilities, sense of responsibility, traditional belief, and meaning in life in the Chinese context.

This study reveals that functional disabilities is negatively related with social network, and social network is positively related with meaning in life. In other words, declining functional abilities are associated with lower levels of social network and meaning in life. Social network fully mediates the influence of functional disabilities on quality of life. This result confirms the findings of previous studies that losing contact with family and friends may reduce the meaning in life of elders. The passing away of the spouse also creates a loss of the sense of meaning in life (Koren & Lowenstein, 2008). Hence, finding meaning in the face of declining functional abilities and maintaining social networks are important to the well-being of the Chinese elders.

Results of this study suggest that meaning in life and social network play an important role to mitigate the impact from declining functional disabilities. As meaning in life is positively related to quality of life among Chinese elders, encouraging these elders to continue to search for new meaning in life can enhance their well-being. Meaning in life seems to create the similar effects on well-being in the Chinese societies as that in Japan and Korea (Ju et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2010). Developing a sense of self-responsibility toward ones’ well-being and taking the responsibility to serve society and other people are ways to enrich the meaning in life of elders (H. Zhang et al., 2014). This sense of positive meaning toward the decline in functional abilities is consistent with traditional Chinese values.

To improve well-being, elders facing deterioration in health and activity levels can develop new sources of meaning in their life via learning to live intentionally and purposefully as well as to reevaluate what is important in their life (Park, Malone, Suresh, Bliss, & Rosen, 2008). Learning not to view decline in functional abilities as a serious loss but to live by purposively participating in health-related decisions can help elders in facing aging. Moreover, the protective role of a social network cannot be neglected. This study suggests that social networks directly enhance quality of life and indirectly enhance it via the increase in meaning in life. Formal support such as home care services can improve the Chinese elder’s quality of life (Cheung et al., 2005). Mutual social support from neighbors and friends are other sources that should be further facilitated in the community. Instrumental support received from the personal network has been found to provide more positive effects on the well-being of Chinese elders than that received from professional caregivers (Y. Y. Chen et al., 2016). However, the study revealed that Chinese elders with lower educational attainment had a lower score in presence of meaning and search for meaning, a narrower social network, and lower levels of quality of life than those with higher educational attainment. Therefore, elderly service providers should pay more attention to elders with low educational attainment. Elderly service centers in the community can serve as a hub to foster social connection among these elders (Lum et al., 2016), and to help them to search and maintain positive meaning in aging.

The present study has several limitations. The study focused only on three aspects of quality of life, which may not cover the broader dimensions. Therefore, a more comprehensive scale that considers different aspects may be more appropriate to measure quality of life of Chinese elders. The sample in this study included only 339 participants, and because non-probability sampling methods were employed, bias may emerge. A random sampling method is recommended to obtain representative findings in further study. Finally, a longitudinal study is necessary to examine the effect of change in functional disability, meaning in life, and social network on the quality of life of Chinese elders.

Despite the above limitations, this study enriches the knowledge of the factors related to quality of life among poor community-dwelling Chinese elders. The findings confirmed the role of social network and meaning in life as psychological and collective resources that can mitigate the negative effects of functional disability on the quality of life in the Chinese context. This study also revealed that Chinese elders with low educational attainment tend to have low levels of meaning in life and social network, which required more service support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Raymond Chi-Fai Chui  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6431-2511

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6431-2511

References

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. (2009). The psychometric properties of the Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire, compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2009, Article 298950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brovold T., Skelton D. A., Sylliaas H., Mowe M., Bergland A. (2014). Association between health-related quality of life, physical fitness, and physical activity in older adults recently discharged from hospital. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity, 22, 405-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M., Cudeck R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen K., Long J. (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. (2009). Thematic Household Survey report no. 40: Socio-demographic profile, health status and self-care capability of older persons. Hong Kong: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. (2015). Quarterly Report on General Household Survey: July to September 2015. Hong Kong: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S., Shoumei J., Chiu H., Wai-Tong C., Thompson D. R., Yan H., Lam L. (2009). Subjective health-related quality of life of Chinese older persons with depression in Shanghai and Hong Kong: Relationship to clinical factors, level of functioning and social support. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24, 355-362. doi: 10.1002/gps.2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Hicks A., While A. E. (2013). Quality of life of older people in China: A systematic review. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 23, 88-100. doi: 10.1017/s0959259812000184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Y., Wong G. H., Lum T. Y., Lou V. W., Ho A. H., Luo H., Tong T. L. (2016). Neighborhood support network, perceived proximity to community facilities and depressive symptoms among low socioeconomic status Chinese elders. Aging & Mental Health, 20, 423-431. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1018867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J. C. K., Kwan A. Y. H., Chan S. S. C., Ngan R. M. H., Ng S. H., Leung E. M. F., Lau A. (2005). Quality of life in older adults: Benefits from caring services in Hong Kong. In Shek D. T. L., Chan Y. K., Lee P. S. N. (Eds.), Quality-of-life research in Chinese, Western and global contexts (Vol. 25, pp. 291-334). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer L., Nordenfelt L., Ternestedt B. M. (2008). Three nursing home residents speak about meaning at the end of life. Nursing Ethics, 15, 97-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugan G. (2014). Meaning-in-life in nursing-home patients: A correlate with physical and emotional symptoms. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 1030-1043. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jafary F., Farahbakhsh K., Shafiabadi A., Delavar A. (2011). Quality of life and menopause: Developing a theoretical model based on meaning in life, self-efficacy beliefs, and body image. Aging & Mental Health, 15, 630-637. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.548056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju H., Shin J. W., Kim C. W., Hyun M. H., Park J. W. (2013). Mediational effect of meaning in life on the relationship between optimism and well-being in community elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56, 309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P., Warren S., Madill H., Hadley M. (1999). Quality of life of stroke survivors. Quality of Life Research, 8, 293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren C., Lowenstein A. (2008). Late-life widowhood and meaning in life. Ageing International, 32, 140-155. doi: 10.1007/s12126-008-9008-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. (2004). Stressors arising in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 59(5), S287-S297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. (2007). Evaluating the stress-buffering function of meaning in life among older people. Journal of Aging and Health, 19, 792-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau L. K. P., Mok E., Lai T., Chung B. (2013). Quality-of-life concerns of Chinese patients with advanced cancer. Social Work in Health Care, 52, 59-77. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.728560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M. P., Brody E. M. (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9, 179-186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J. (2005). An exploratory study on the quality of life of older Chinese people living alone in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 71, 335-361. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-8027-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Chi I., Xu L. (2013). Life satisfaction of older Chinese adults living in rural communities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 28, 153-165. doi: 10.1007/s10823-013-9189-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. C., Li C. I., Chang C. K., Liu C. S., Lin C. H., Meng N. H., Li T. C. (2011). Reduced health-related quality of life in elders with frailty: A cross-sectional study of community-dwelling elders in Taiwan. PLoS ONE, 6(7), e21841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. J., Guo Q. (2007). Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1275-1280. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubben J., Gironda M. (2004). Measuring social networks and assessing their benefits. In Phillipson C., Allan G., Morgan D. (Eds.), Social networks and social exclusion: Sociological and policy perspectives (pp. 20-34). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lubetkin E. I., Jia H., Franks P., Gold M. R. (2005). Relationship among sociodemographic factors, clinical conditions, and health-related quality of life: Examining the EQ-5D in the U.S. general population. Quality of Life Research, 14, 2187-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum T. Y. S., Lou V. W. Q., Chen Y., Wong G. H. Y., Luo H., Tong T. L. W. (2016). Neighborhood support and aging-in-place preference among low-income elderly Chinese city-dwellers. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 71, 98-105. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Li Y., Wang J., Zhu H., Yang W., Cao R., Feng M. (2015). Quality of life is related to social support in elderly osteoporosis patients in a Chinese population. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0127849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. H., Song X. Y., Lee S. Y., Kwok T. (2008). Longitudinal analysis of quality of life for stroke survivors using latent curve models. Stroke, 22, 2795-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. L., Malone M. R., Suresh D. P., Bliss D., Rosen R. I. (2008). Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research, 17, 21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S., Wójcicki T., McAuley E. (2013). Physical activity and quality of life in older adults: An 18-month panel analysis. Quality of Life Research, 22, 1647-1654. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0319-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvimäki A., Stenbock-Hult B. (2000). Quality of life in old age described as a sense of well-being, meaning and value. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 1025-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J., Zhang Q., Lin T., Shen J., Li D. (2014). Well-being of elderly stroke survivors in Chinese communities: Mediating effects of meaning in life. Aging & Mental Health, 18, 435-443. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.848836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek D. T. L. (1992). Meaning in life and psychological well-being: An empirical study using the Chinese version of the Purpose in Life questionnaire. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 153, 185-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M. F., Frazier P., Oishi S., Kaler M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80-93. [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Liu K. U. N., Webber M., Shi L. (2017). Individual social capital and health-related quality of life among older rural Chinese. Ageing & Society, 37, 221-242. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X15001099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. C., Burton M., Griffin M. T., Fitzpatrick J. J. (2010). Self-transcendence, spiritual well-being, and spiritual practices of women with breast cancer. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 28, 115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Shan W., Jiang A. (2014). The meaning of life and health experience for the Chinese elderly with chronic illness: A qualitative study from positive health philosophy. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 20, 530-539. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Shi W., Huang Z., Gao D., Guo Z., Liu J., Chongsuvivatwong V. (2016). Influence of culture, residential segregation and socioeconomic development on rural elderly health-related quality of life in Guangxi, China. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14, 98-98. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0499-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]