Abstract

Data about a muscle’s fibre pennation angle and physiological cross-sectional area are used in musculoskeletal modelling to estimate muscle forces, which are used to calculate joint contact forces. For the leg, muscle architecture data are derived from studies that measured pennation angle at the muscle surface, but not deep within it. Musculoskeletal models developed to estimate joint contact loads have usually been based on the mean values of pennation angle and physiological cross-sectional area.

Therefore, the first aim of this study was to investigate differences between superficial and deep pennation angles within each muscle acting over the ankle and predict how differences may influence muscle forces calculated in musculoskeletal modelling. The second aim was to investigate how inter-subject variability in physiological cross-sectional area and pennation angle affects calculated ankle contact forces.

Eight cadaveric legs were dissected to excise the muscles acting over the ankle. The mean surface and deep pennation angles, fibre length and physiological cross-sectional area were measured. Cluster analysis was applied to group the muscles according to their architectural characteristics. A previously validated OpenSim model was used to estimate ankle muscle forces and contact loads using architecture data from all eight limbs.

The mean surface pennation angle for soleus was significantly greater (54%) than the mean deep pennation angle. Cluster analysis revealed three groups of muscles with similar architecture and function: deep plantarflexors and peroneals, superficial plantarflexors and dorsiflexors. Peak ankle contact force was predicted to occur before toe-off, with magnitude greater than five times bodyweight. Inter-specimen variability in contact force was smallest at peak force.

These findings will help improve the development of experimental and computational musculoskeletal models by providing data to estimate force based on both surface and deep pennation angles. Inter-subject variability in muscle architecture affected ankle muscle and contact loads only slightly. The link between muscle architecture and function contributes to the understanding of the relationship between muscle structure and function.

Keywords: Ankle, muscle architecture, surface/deep pennation angle, physiological cross-sectional area, joint reaction forces

Introduction

A muscle’s architecture (particularly its physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA), fibre pennation angle (PA) and optimal fibre length) is an established predictor of its force generation and excursion,1 in both musculotendon-actuator-2,3 and electromyography (EMG)-activation-data based4 models. Some models of musculoskeletal function (both experimental5–10 and computational2,11–13) apply the aforementioned models to calculate the distribution of load between different muscles, demonstrating that reliable data about muscle architecture are important in biomechanical research and clinical practice.

Human muscle architecture has been investigated using ultrasound14–21 and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),16,22,23 but conventional machines are unable to measure individual muscle fibres. Given the limitations of current-generation medical imaging, the gold standard for obtaining muscle architecture data remains dissection of cadavers.1 Few studies have used cadaveric material to measure the architecture of the dorsiflexor, plantarflexor and peroneal muscles acting across the ankle joint;24–28 the two most cited studies24,28 investigated only two and three specimens. More recently, Ward et al.27 published a study of 21 lower limbs, which for the first time, provided data about the variation in muscle architecture. However, similar to previous studies,24,28 only surface measurements of muscle PAs were performed, despite the fact that there is evidence suggesting that there may be a difference between the PAs at the surface and the interior of a muscle,29 particularly for bi- or multi-pennate muscles with large PCSAs. Musculoskeletal models12,25 use a number of elements to simulate the forces exerted by muscles, particularly larger muscles, implying that it can be advantageous to use different architectural parameters, including PA, for each of these elements. This emphasises the potential benefit of obtaining PA data for both a muscle’s surface and its interior.

As implied above, inter-subject variability in muscle architecture is a source of uncertainty in biomechanical models involving application of simulated muscle forces. Such variability has been addressed within the framework of parametric sensitivity analyses, and its application is currently gaining popularity for use in musculoskeletal modelling.30 In view of the fact that differences in muscle architecture could affect estimates of force exerted by the muscle along its line(s) of action, which would, in turn, impact upon the outcomes of musculoskeletal modelling employing data of muscle architecture, the first aim of this study was to investigate potential differences between superficial and deep PAs within the muscles acting across the human ankle. The second aim was to investigate how inter-subject variability in muscle architecture affects ankle muscle and joint reaction forces (also referred to as talocrural contact loads) estimated through musculoskeletal modelling.

Methods

Measurements of muscle architecture

Eight formalin-embalmed cadaveric lower limbs from eight adult males (four right and four left; mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) age of donors: 80 ± 5 years; height: 173 ± 1 cm), with no known anatomical abnormalities, were investigated in this study. All cadavers were donated and the study was performed at the Human Anatomy Unit, Charing Cross Campus, Imperial College London, in compliance with the provisions of the UK Human Tissue Act (2004).

The lower limbs were dissected to excise all muscles acting across the ankle: 1) the superficial plantarflexors: gastrocnemius, soleus and plantaris; 2) the deep plantarflexors: flexor hallucis longus (FHL), flexor digitorum longus (FDL) and tibialis posterior (TP); 3) the dorsiflexors: extensor hallucis longus (EHL), extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and tibialis anterior (TA) and 4) the peroneal muscles: peroneus longus (PL) and peroneus brevis (PB). For the purposes of the current study, peroneus tertius (PT) was included as a part of EDL, because of its small size and the fact that during dissections the muscle belly was not accurately separable from that of EDL.31

Individual muscle bellies were dissected from their tendons at the musculotendinous junction. Fat, nerves, blood vessels and fascia were removed from each muscle and care was taken to avoid cutting or stretching its fibres. Muscle body volumes were then measured using water displacement (±1 mL accuracy for the smallest muscles, to ±5 mL for the largest).

Muscle length was defined as the distance from the most proximal point of the muscle to the centre of its musculotendinous junction.27,28 It was measured from an overhead digital image of the muscle together with a millimetre scale, using an image-analysis script coded in MATLAB® (version R2013a, MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

To measure surface PA, bundles of superficial muscle fibres were gently separated from each other using fine forceps and a scalpel, to allow better visualisation of their orientation. Digital images of the muscle surface were then taken from directly above using a photo-copy stand (Figure 1). The PAs of superficial muscle fibres with an approximately even distribution along the muscle length were subsequently measured using an image-analysis script coded in MATLAB and recorded to the nearest degree. The PA was defined as the angle between the line connecting the tendinous insertion and end points of the fibre, with the tangent to the tendon or aponeurosis at the fibre attachment point (Figure 1(a)).16,32

Figure 1.

Photographs of example muscles ((a and b) soleus and (c) tibialis anterior). Fibre pennation angles (PAs) were measured on the muscle surfaces (a) before they were dissected to allow a clear visualisation of the fibres deep within the muscle (b and c). The images were used to estimate PA as the angle (black arc) between the muscle fibre (blue line) and tendon/aponeurosis (dark red line). The tibialis anterior (c) is an example for a muscle with long fibres and small PA, whereas the soleus (a) is the muscle with the shortest fibres and the largest PA. The difference in architecture between the soleus surface (a) and deep within it (b) is also demonstrated.

To measure PAs deep within a muscle, it was cut lengthwise along its tendon axis into two or three pieces in such a way that the muscle fibres were visualised in the plane of the cut.33 Groups of fibres distributed approximately evenly within the muscle were gently separated from each other and digital images were taken (Figure 1(b) and (c)) to allow measurement of PAs of deep muscle fibres as described above (measurements of the deep PAs were not possible in the plantaris, because it was too small and thin to be cut as described). The mean combined PA for each individual muscle was then calculated as the average of its mean surface and deep PAs.

To determine fibre length, muscle fascicles were dissected from each muscle with an approximately even distribution along its length.24,26,28 The fascicles were immersed in 20% w/w nitric acid for 48–96 h to digest connective tissue and allow separation of approximately 0.1-mm-thick bundles (the thinnest bundles we were able to isolate intact) from the two tendinous intersections or aponeurotic fascia bands between which they extended, with the aid of a dissecting microscope.24 Fibre lengths were estimated by directly measuring bundle lengths using a millimetre scale, while holding the bundles straight without stretching. The mean normalised fibre length was calculated as the mean fibre length divided by the length of the whole muscle.24,28

The PCSA of each muscle was calculated by dividing the muscle volume by its mean fibre length as reported previously.16,24,26,34 Normalised PCSA was calculated by dividing the muscle PCSA by the sum of PCSAs of all ankle-crossing muscles of that leg; normalised PCSAs may be used to estimate absolute PCSAs based on other anthropometric characteristics and also allow consistent comparison between subjects.24,35 Reduced PCSA, indicative of the force that a muscle can apply along its line of action, was calculated as the product of its PCSA and cosine of the mean combined PA.23,27,28,36 The anatomical cross-sectional area (ACSA) of each muscle was calculated by dividing its volume by its measured length.36

Data were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction for post hoc analysis was used to explore the interaction between different muscles, the location of PA measurement (surface or deep) and the value of mean PA. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance tests were used to investigate differences in the mean fibre length, mean surface PA, mean deep PA, mean combined PA, volume and PCSA between different muscles. Mann–Whitney tests were used to identify significant differences between groups of muscles. Significance was set at P<0.05. After visually identifying three clusters of data points in a three-dimensional (3D) scatter diagram of the volumes, the mean fibre lengths and mean combined PAs of all muscles examined, the k-means clustering method37 was used to group data, with the number of clusters set to 3. All data-analysis techniques were applied using SPSS® Statistics (Version 21; IBM Corp., NY, USA) and MATLAB. The plantaris muscle was excluded from the analysis due to the difficulty of acquiring deep PA measurements, as well as its minor role in controlling ankle movement.

To determine the test–retest reliability of the mean surface and deep PA measurement method, the procedure described above was repeated five times over five consecutive days using a soleus muscle from a randomly selected cadaver. The measurements were then analysed using the Fisher original intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Analysis revealed high reliability, with a mean PA test-retest difference of less than 3° and ICCs of .91 and .80 for the surface PA and deep PA, respectively.

Musculoskeletal modelling

A previously validated musculoskeletal model implemented in OpenSim11 (Gait239238) was adapted to estimate ankle muscle forces and contact loads applying the muscle architecture data acquired as described above. The musculoskeletal model, which is based on the pioneering work by Delp et al.,2 has 23 degrees of freedom and 92 musculotendon actuators (with adjustable architectural parameters) to simulate the kinematics and dynamics of the two lower limbs, pelvis and torso. Focusing on the foot and ankle, separate segments are assigned to the following rigid bodies onto which the muscles are attached: (1) tibia and fibula, (2) talus, (3) calcaneus, navicular, cuboid, cuneiforms and metatarsals and (4) phalanges. The talocrural and subtalar joints are both modelled as frictionless revolute joints allowing only flexion and version, respectively. Muscles modelled include those dissected (apart from the plantaris): gastrocnemius (two elements), soleus, FHL, FDL, TP, EHL, EDL, PT, TA, PB and PL. Muscle paths are adjusted using via points and wrapping surfaces where such are necessary to simulate the physiological scenario and prevent muscle lines of action from passing through bone as the joint moves. The scaled version of the model used herein represents a subject that is approximately 180 cm tall and has a mass of 72.6 kg; the musculotendon architectural parameters (including PCSA, PA and optimal fibre length) are derived from two of the aforementioned studies.24,28 Muscle isometric strength is considered proportional to the PCSA,2,39 normally assuming specific tension (muscle tensile stress, which is the force exerted by the muscle per unit of PCSA) of 61 N/cm2 as described previously.2,38–40 This value falls within the range of 35–137 N/cm2 that has previously been reported41 to only marginally influence muscle and joint reaction forces predicted through musculoskeletal modelling.

The simulation was set based on the reported kinematics and ground reaction forces occurring during self-selected speed level walking of an adult healthy male;38,42 the data are downloadable as part of a tutorial package available in the SimTk Project website.43 In view of the fact that the forces generated by the muscles acting over the ankle largely determine the joint reaction force at the talocrural joint, these forces were calculated in the OpenSim environment applying the static optimisation approach described previously11,44,45 (and implemented in similar studies estimating contact forces occurring in the hip, for example13,46) and utilising the Thelen47 muscle model, while assuming that the problem was static at each frame. Model outputs were calculated utilising the model’s nominal muscle architecture values,24,28 as well as the muscle PA and PCSA data from each of the eight lower limbs investigated in this study to create subject-specific model variants; other parameters (including optimal fibre length, which was not measured in this study; see below) were not altered and kept at their nominal values. The forces generated by EDL and PT were assumed to act through the EDL for the reasons described above; accordingly, the actuator simulating the EDL was assigned PCSA representing the sum of the PCSAs of the two muscles, while that simulating the PT was disabled. Contact loads occurring in the talocrural joint were then calculated. During this procedure, kinematic data, together with all external forces and estimated muscle forces, are used by the software to calculate the resultant load at the joint through dynamic analysis.43,48

Results

Measurements of muscle architecture

The sample means and SEMs of muscle volumes, lengths, mean fibre lengths, mean normalised fibre lengths, mean fibre surface PAs, mean fibre deep PAs, mean fibre combined PAs, ACSAs, PCSAs, reduced PCSAs and normalised PCSAs are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean outcome measures (muscle volumes, lengths, mean fibre lengths, mean normalised fibre lengths, mean fibre surface PAs, mean fibre deep PAs, mean fibre combined PAs, ACSAs, PCSAs, reduced PCSAs and normalised PCSAs) for all muscles investigated. The peroneus tertius was considered a part of extensor digitorum longus. Values represent sample means ± standard errors of the mean. ACSA: anatomical cross-sectional area; N/A: not available; PA: pennation angle; PCSA: physiological cross-sectional area.

| Muscle | Volume (mL = cm3) | Length (cm) | Mean fibre length (cm) | Mean normalised fibre length (cm) | Mean fibre surface PA (°) | Mean fibre deep PA (°) | p-Value for the difference between surface and deep PAa | Mean fibre combined PA (°) | ACSA (cm2) | PCSA (cm2) | Reduced PCSA (cm2) | Normalised PCSA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial plantarflexors | ||||||||||||

| Gastrocnemius | 145 ± 18 | 25.2 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 0.16 ± 0.007 | 20 ± 4 | 18 ± 2 | 1 | 18 ± 2 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 36 ± 5 | 34 ± 4 | 17 ± 1.2 |

| Soleus | 224 ± 25 | 30.7 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.07 ± 0.005 | 40 ± 3 | 26 ± 3 | 0.006* | 32 ± 3 | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 98 ± 9 | 82 ± 8 | 47 ± 1.1 |

| Plantaris | 4 ± 1 | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 0.41 ± 0.023 | 9 ± 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Deep plantarflexors | ||||||||||||

| Flexor hallucis longus | 36 ± 3 | 22.8 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 0.15 ± 0.009 | 20 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 | 1 | 19 ± 2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 11 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 5 ± 0.5 |

| Flexor digitorum longus | 18 ± 2 | 26.0 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.002 | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 2 | 1 | 16 ± 2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.2 |

| Tibialis posterior | 56 ± 5 | 28.9 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.10 ± 0.003 | 17 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 | 1 | 17 ± 1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 20 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | 10 ± 0.9 |

| Dorsiflexors | ||||||||||||

| Extensor hallucis longus | 18 ± 2 | 26.3 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.4 | 0.28 ± 0.013 | 10 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 1 | 10 ± 1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.3 | 2 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| Extensor digitorum longus | 42 ± 5 | 35.0 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | 0.20 ± 0.011 | 12 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 0.755 | 11 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 6 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.3 |

| Tibialis anterior | 65 ± 5 | 28.2 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 0.24 ± 0.010 | 13 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 0.430 | 11 ± 1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 5 ± 0.2 |

| Peroneals | ||||||||||||

| Peroneus brevis | 22 ± 3 | 23.2 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 0.15 ± 0.011 | 18 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 0.387 | 16 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 7 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.4 |

| Peroneus longus | 44 ± 4 | 26.5 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 0.14 ± 0.008 | 19 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | 0.104 | 16 ± 2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 13 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 | 6 ± 0.5 |

After applying Bonferroni correction (multiplying the P-value by the number of comparisons, that is, 10).

There was a significant interaction between muscle type, location of PA (surface or deep) and mean PA (P = 0.009). Post hoc analysis revealed that for soleus, the mean (±SEM) surface PA was significantly greater than the mean deep PA (40° ± 3° compared with 26° ± 3°; P = 0.006 after Bonferroni correction; Table 1). There was no significant difference between the mean surface PA and mean deep PA for any of the other muscles investigated (P > 0.05 for all muscles).

There was a strong linear correlation (0.7 ≤ R2 ≤ 1) between PCSA and ACSA for gastrocnemius, FDL, TP, EHL, PB and PL, and a moderate linear correlation (0.4 ≤ R2 < 0.7) for soleus, FHL, EDL and TA (Table 2). A positive linear relationship was observed between the mean deep and surface PAs of soleus (R2 = 0.60)

Table 2.

Linear curve fitting coefficients describing the relationship between PCSA and ACSA for each muscle (PCSA = a × ACSA, where a is the coefficient). R2 values, along with ranges of ACSA and PCSA for which the relationship was derived, are also indicated. ACSA: anatomical cross-sectional area; PCSA: physiological cross-sectional area.

| Muscle | Linear curve fitting coefficient (a) | ACSA range (cm2) | PCSA range (cm2) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrocnemius | 6.3 | 3.1–9.1 | 22.0–65.5 | 0.85 |

| Soleus | 12.5 | 4.6–13.6 | 75.1–152.2 | 0.44 |

| Flexor hallucis longus | 6.6 | 1.2–2.6 | 7.3–15.7 | 0.48 |

| Flexor digitorum longus | 7.5 | 0.5–1.1 | 3.2–8.4 | 0.98 |

| Tibialis posterior | 10.3 | 1.4–2.9 | 13.1–27.4 | 0.83 |

| Extensor hallucis longus | 3.6 | 0.5–1.0 | 1.4–4.1 | 0.83 |

| Extensor digitorum longus | 5.0 | 0.8–1.8 | 4.1–8.8 | 0.53 |

| Tibialis anterior | 4.2 | 1.8–3.2 | 6.6–13.6 | 0.63 |

| Peroneus brevis | 7.6 | 0.6–1.5 | 3.9–14.0 | 0.86 |

| Peroneus longus | 8.0 | 1.2–2.4 | 9.0–22.7 | 0.70 |

where PAs and PAd are the surface and deep PAs, respectively.

Three clusters of data points were identified by analysis of a scatter diagram of the volumes, mean fibre lengths and mean combined PAs of all 80 muscles examined, utilising the k-means method (Figure 2). These clusters were (1) superficial plantarflexors (gastrocnemius, soleus), (2) dorsiflexors (EDL, EHL, TA) and (3) deep plantarflexors (FDL, FHL, TP) and peroneals (PB, PL). Only 4/80 points were assigned by the algorithm to a cluster different than that of their compartment. Significant differences in combined PA, fibre length, volume and PCSA were found between the three muscle groups (Mann–Whitney test P < 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

A scatter diagram showing volume, mean fibre length and mean PA (combined) from all 80 muscles examined in the study, with data points visually classified into three clusters (black ovals) identified as (1) superficial plantarflexors (gastrocnemius, soleus), (2) dorsiflexors (EDL – extensor digitorum longus; EHL – extensor hallucis longus; TA – tibialis anterior) and (3) deep plantarflexors (FDL – flexor digitorum longus; FHL – flexor hallucis longus; TP – tibialis posterior) and peroneals (PB – peroneus brevis; PL – peroneus longus). The grey labels indicate the outcome of a single iteration of the k-means clustering algorithm, which in this iteration was in agreement with the visual observations in 76 of 80 data points.

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plots comparing medians (red bands), means (black ‘+’ signs) and ranges (interquartile ranges, blue boxes; most extreme data points not considered outliers, black whiskers; outliers, red ‘+’ signs) of data (mean fibre length, mean combined PA, volume and PCSA) collected from all 80 muscle specimens examined in the study and classified into three clusters (deep flexors/plantarflexors + peroneals, superficial flexors/plantarflexors, and extensors/dorsiflexors, as visualised in Figure 2). Asterisks indicate significant differences between clusters according to the Mann–Whitney test (P < 0.05).

Musculoskeletal modelling

Plots of estimates of muscle forces acting during the stance phase of gait (normalised to bodyweight, BW), obtained with the OpenSim static optimisation algorithm using the PA and PCSA values acquired from the eight limbs dissected in the current study, together with those obtained using the nominal values of the OpenSim model, are given in Figure 4. Gastrocnemius and soleus were the two muscles generating the largest forces, with the peak values occurring before toe-off (~75% stance phase for gastrocnemius, ~92% stance phase for soleus), each exceeding two times BW (Figure 4(a)). The total force generated by the dorsiflexors was estimated by the model to peak just when mid-stance starts (~17% stance phase) at 0.7–0.9 BW (depending on the architectural properties applied; Figure 4(b)), with the TA accounting for at least 75% of that force. The forces exerted by the peroneals were even smaller, with peak total force equivalent to or smaller than 0.25 BW at heel strike (0% stance phase; Figure 4(c)). Differences between muscle forces calculated assuming different architectural properties were generally minor, as demonstrated in Figure 4. The smallest difference (approximately 2% at peak force) was calculated for the total force generated by the plantarflexors, which formed the muscle group predicted to exert the largest forces (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

Plots showing estimates of muscle forces (normalised according to bodyweight, BW) exerted during a single cycle of the stance phase of gait. Data were derived from the OpenSim simulation, implementing the nominal PA and PCSA values used in the OpenSim Gait2392 model (thick lines) and those obtained from dissections of eight cadaveric specimens (mean forces across all specimens: dashed lines; ±1 standard deviation: shaded area). Forces produced by the ankle (a) plantarflexors, (b) dorsiflexors and (c) peroneals are plotted separately.

EDL: extensor digitorum longus; EHL: extensor hallucis longus; FDL: flexor digitorum longus; FHL: flexor hallucis longus; PB: peroneus brevis; PL: peroneus longus; PT: peroneus tertius; TA: tibialis anterior; TP: tibialis posterior.

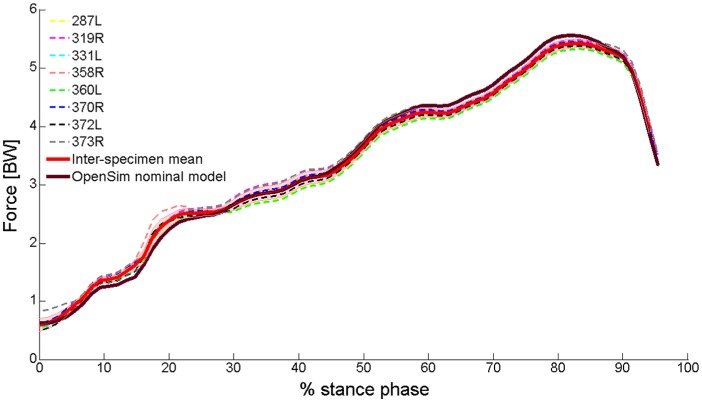

Plots of the model-predicted total reaction force acting at the talocrural joint during the stance phase (normalised according to BW) are shown in Figure 5. Differences between contact forces calculated assuming different architectural properties were minor. For all specimens, peak force occurred before toe-off (75%–83% stance phase), with a magnitude larger than five times BW (at 75% stance phase, for example, inter-specimen mean contact force: 5.0, standard deviation: 0.1, range: 4.9–5.1 BW). During the earlier stance phase, however, when predicted contact forces were smaller, differences between outputs obtained for different architectural properties were larger (e.g. an approximately 15% difference between the largest and smallest estimates at 20% stance phase).

Figure 5.

Plots showing estimates of the total contact force (normalised according to BW) acting in the talocrural joint during a single cycle of the stance phase of gait. Data were derived from the OpenSim simulation, implementing the nominal PA and PCSA values used in the OpenSim Gait2392 model (thick wine-red line) and those obtained from dissections of eight cadaveric specimens (dashed lines in various colours; the thick red line indicates the mean across all specimens, while the shaded area represents ±1 standard deviation; legend labels indicate the specimen numbers).

Discussion

Knowledge of a muscle’s architecture is important for predicting the forces that it generates, which is crucial in experimental and computational biomechanical modelling, including musculoskeletal models.27,39 This study is the first to compare surface with deep muscle fibre PAs, revealing a significant difference between those of soleus, with the mean surface PA being significantly greater (by 54%) than the mean deep PA (Table 1). This would result in a 15% underestimation of the force exerted by soleus (which is one of the strongest muscles acting over the ankle) when calculated using surface rather than deep PA measurements and assuming that the muscle force is proportional to the cosine of the PA.4

In this study, the PCSAs of the muscles acting over the ankle joint were 3.7- to 12.3-fold greater than their ACSAs (Table 2), in agreement with previous findings.23,36 The values derived for individual muscles can be useful for estimating a muscle’s PCSA from its ACSA, which can be measured easily in vivo using ultrasound or MRI.23,35,49 In order to test this claim, we used the mean muscle volume and muscle length data reported in one of these studies35 (only gastrocnemius, soleus, FHL, FDL, TP and TA, for which data were available), together with the ACSA-to-PCSA values that we derived, to estimate the muscle PCSAs; these were compared to PCSA estimates obtained through dividing the muscle-volume-to-muscle-length ratio from Handsfield et al.35 by the optimal fibre-length-to-muscle-length ratio from Ward et al.27 (as implemented in Handsfield et al.35). Estimates made according to the former approach were similar to those obtained through the latter one, though 10%–40% larger (Supplementary Table 2), which is within the range of the inter-specimen variability in muscle volume (Table 1).

There are two principal findings to the musculoskeletal modeling in the current study; the first is that a reaction force greater than five times BW was calculated for the talocrural joint between the heel rise and toe-off phases of the gait cycle (Figure 5); the second is that inter-limb variation in muscle PCSA and mean fibre PA (manifested in both variations between the cadaveric specimens used in this study and variations between these and the nominal muscle architecture values of the OpenSim model adapted in this study) only marginally affected ankle contact forces, including those acting between the heel rise and toe-off. The muscle forces that generated this joint reaction force were affected by inter-limb variation to a greater extent than the joint reaction forces. Yet, the total force generated by the plantarflexors, the muscle group exerting the largest forces acting over the ankle, demonstrated inter-subject variation of only 2% at peak force. This finding is supported by the model suggested by Zajac,3 demonstrating that the effects of fibre PA on musculotendon forces are significant only in especially large (i.e. larger than 23°) PAs (where all combined PAs measured in this study, excluding that of soleus, were smaller than 20°). This can explain the minor effect that the variation in muscle architecture had on peak contact force. To our knowledge, this is the first time that contact forces occurring in the ankle have been calculated using a contemporary musculoskeletal modelling platform (such as OpenSim, AnyBody® or LifeModeler®) while exploring the sensitivity of the model outcomes to muscle architectural characteristics of PCSA and fibre PA.

The muscle architecture data (Table 1) are generally in good agreement with those reported in similar studies available in the literature (detailed comparison with previous cadaveric studies is available in Supplementary Table 1).24–28 Specifically, trends in the current data are consistent with previous studies, showing that soleus has the largest combined PA while plantaris, followed by the dorsiflexors, has the smallest. The dorsiflexors have the longest fibres and soleus, followed by gastrocnemius, have the largest volume and PCSA. However, for all muscles investigated in this study, the mean fibre lengths and mean normalised fibre lengths were shorter than those reported previously. This difference may be due to fibre lengths being ‘normalised’ according to sarcomere lengths (to give optimal fibre lengths) in two of the previous studies.26,27 Additionally, in this study, combined PAs were consistently found to be larger than those reported in the literature, which may be linked to differences in measurement techniques (using image analysis rather than a palpator). It should further be noted that the muscle architectural characteristics directly related to the muscle size (volume, ACSA and PCSA) reported here are typically 1.5–2 times smaller than in previous studies employing MRI to explore the leg musculature in young, healthy and/or physically active subjects.23,35,49,50 This discrepancy – attributable to pre-death muscle atrophy (as a result of sarcopenia, inactivity and pathology) in the cadavers dissected in this study35– was compensated in our musculoskeletal model with using a value of muscle specific tension (61 N/cm2) higher than reported in the literature, as suggested previously.39,40

The muscle and joint reaction forces calculated in this study are largely similar to those reported in the literature,51–54 including studies implementing musculoskeletal modelling in the OpenSim environment.41,55 In particular, the current estimates of both the total and vertical components of the reaction forces acting in the talocrural joint through the stance phase of gait were consistent with those in the literature, both in trend and magnitude.41,55,51–53 Of special interest is that for nearly all studies, peak force occurred before toe-off, with magnitude above five times BW. The exception for this is the study by Procter and Paul,53 which estimated the total talocrural contact force to peak at approximately 3.5 BW. This lower finding could be due to their model disregarding the inertial contributions of the bone components to the joint reaction forces, and assuming that antagonist muscle groups do not act simultaneously, which may not be the physiological reality. The study by Hardt54 similarly predicted the total ankle contact force to peak at 3.5 BW; however, this force was calculated as the sum of muscle forces predicted utilising the optimisation-based musculoskeletal model developed by the researcher, and inertial and gravitational forces reported in another study (and not calculated by Hardt). Also, one of the assumptions of the optimisation algorithm was that only few of the muscles modelled were active at any time point, which possibly resulted in an underestimation of the calculated contact forces. A recently published OpenSim model of the lower limb by Valente et al.41 predicted the largest muscles acting over the ankle to generate forces similar to those calculated in this model (gastrocnemius and soleus generating peak forces larger than 2 BW before toe-off, and TA generating force equivalent to approximately 0.6 BW when mid-stance starts). This model also predicted peak ankle contact force to be only slightly higher than in this study (approaching 6 BW). Perturbations in model inputs aimed at investigating the sensitivity of muscle and joint-reaction forces to uncertainties in muscle specific tension and musculotendon geometry affected the calculated muscle and joint reaction forces only to a moderate extent, which is in a further agreement with the findings of this model. A very recent subject-specific OpenSim model by Prinold et al.55 predicted peak ankle reaction forces to equal 4.5 or 6 BW (depending on the subject) and to be more sensitive to perturbations in muscle attachments, but these were calculated for three adolescents suffering from juvenile idiopathic arthritis rather than healthy adults.

The OpenSim simulation conducted in this study estimated contact forces occurring in other joints, including the hip joint. The latter were in a quantitatively and qualitatively good agreement with hip contact forces calculated in a previous experimentally validated study.13,46 The current finding that muscle force estimations are considerably more sensitive to variations in muscle PCSAs than joint contact forces also concurs with the results of a previous study employing musculoskeletal modelling of the hip joint.56

A limitation of this study may be the use of formalin-fixed specimens, because embalming may have affected muscle architecture. However, Cutts57 reported that embalming caused only ~2% shrinkage of excised leg muscles, indicating that the effect of fixation on architecture is marginal. Additionally, muscle PCSA, fibre length and PA in vivo are affected by joint position and muscle activity,3,14,16,17,19 giving an inherent limitation to the use of cadaveric material. The specimens investigated in this study were from elderly donors, in whom muscle architectural characteristics (particularly those related to the muscle size, including volume, ACSA and PCSA) could be different to those in a younger population.20,34,58–60 Also, all cadavers investigated in this study were from male donors and these exhibit differences (manifested particularly in the above characteristics) compared with females.35,49,60–62 However, differences in muscle mass between males and females have been shown to be significantly smaller in the lower than in the upper limbs.61 Additionally, sarcomere lengths were not measured in this study despite the fact that they are needed to calculate the optimal fibre length – in which the muscle is assumed to produce maximum force.1,27 A muscle’s PCSA was accordingly calculated as the fracture of the muscle volume and its mean fibre length16,24,26,34– rather than optimal fibre length.25,27 However, sarcomere length data available in the literature are of high accuracy and demonstrate that they are fairly consistent for the musculature acting over the ankle (2.12–3.24 µm27 or 1.89–3.16 µm26). Yet, the modelling presented here neglected the muscles’ force–length relationship and its effect on the muscle isometric strength. Similarly, the PA used as input for the OpenSim model should be that measured at optimal fibre length, and therefore it was assumed that the cadaveric PA values applied to the model in the current study were measured at optimal fibre length. These assumptions, however, are unlikely to have had an impact on the main conclusion of this study, according to which inter-limb variation in muscle PCSA and PA affects ankle-crossing muscle forces to a small extent and talocrural contact forces only marginally; also, a previous study45 found that static-optimisation-predicted hip, knee and ankle joint contact forces were affected by force–length–velocity constraints to a marginal extent, which were also implemented in a recent study.41 Finally, the architectural properties of the tendons (e.g. slack and taut lengths and cross-sectional areas, or length of the entire musculotendon unit) and muscle moment arms were also not measured despite the fact that they can contribute to the accuracy of musculoskeletal modelling.2,39,63 However, high-fidelity datasets of tendon architecture and muscle moment arms are already available in the literature.64–67 The architectural properties of the medial and lateral heads of gastrocnemius are not reported here separately, because the border between them is difficult to distinguish in the muscle belly, and attempts to investigate the heads separately in two cadavers did not reveal any difference in mean fascicle length or fibre PA. Therefore, the same PA and PCSA values were assigned to both elements modelling this muscle in the musculoskeletal model.

The main limitations of the musculoskeletal model employed in this study are associated with the use of gait data from a single subject (although we did implement subject-specific muscle architectural properties). Also, when adjusting the model according to experimentally measured, subject-specific PCSA and PA, the model and gait data were not re-scaled. However, since one of the aims of this study was to explore the effect of the muscle architectural properties on the reaction forces in the talocrural joint, it was expedient to adjust these properties according to the experimental data we acquired, while keeping all other model inputs at their nominal values. Also, in view of the fact that the data used as inputs for the current OpenSim simulation are characteristic of normal level walking of adult healthy males,38,42 the joint reaction load estimations produced by the simulation are likely to be representative of the ‘normal’ physiological condition. Another potential limitation of the model is demonstrated in the considerable differences found between dorsiflexor and peroneal muscle activation profiles as predicted by this model and clinical EMG data available in the literature.4 Despite the fact that qualitative agreement between EMG data and muscle activation profiles has been reported in several studies,3,13,68,69 it has also been demonstrated that surface EMG is not necessarily a reliable predictor of the forces exerted by smaller and/or deeper muscles.4,68 Accordingly, differences similar to those we report here have been previously found in musculoskeletal models of the knee,48,70 for example. These differences can be attributed to EMG being unable to predict passive musculotendon forces (those applied by taut tendons), which are accounted for in the current musculoskeletal model. More importantly, it has also been demonstrated that the musculoskeletal- modelling-predicted activations of the leg musculature (including some muscles acting across the ankle) are affected by the objective function used in the static optimisation algorithm and can therefore substantially deviate from EMG profiles.13,70 A further important limitation of the current contact load estimation is the lack of experimental data to verify the outcomes obtained through computational modelling (where such data collected using instrumented joint replacements are available for the hip, knee and shoulder joints71,72 and have been used to validate model-predicted joint contact forces occurring in the hip13 and knee48,70).

Conclusion

Computational and experimental modelling are crucial research approaches in musculoskeletal research, since ethical and practical considerations limit the collection of data in vivo. The muscle-architecture data reported here may be used to estimate muscle forces through musculoskeletal modelling, which can contribute to the understanding of the roles of the leg muscles and assist in surgical decision-making (e.g. tendon transfer) and ankle prosthesis design. Additionally, this study is the first to demonstrate a difference between surface and deep PAs and provide evidence to group the muscles acting over the ankle joint according to their architecture, thus identifying links with their functional roles. The current study is also one of the first to demonstrate that joint reaction forces calculated in a musculoskeletal model are relatively insensitive to subject-specific muscle PCSA and fibre PA; however, there was a considerable variation in the soleus muscle force calculated for surface compared with deep PA.

Future investigations of muscle architecture should be expanded to include data from female and younger subjects. Also, since the muscle architectural properties assessed in this study are affected by joint position and muscle activity, measurement of muscle architecture in vivo by applying advanced imaging techniques can provide data to improve future musculoskeletal models. Future work could also include a multi-subject study in which the musculoskeletal model described herein would utilise subject-specific gait data to more accurately predict contact forces occurring in the ankle.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank staff at the Human Anatomy Unit at Imperial College London for their help. Dr J Stephen of the Biomechanics Group is thanked for giving meaningful clinical insights to interpret the results. Mr Peter Rosenfeld of the Fortius Clinic is thanked for kindly giving the first author professional guidance about the ankle anatomy.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was partly funded by the British Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (4243), the EPSRC and the Wellcome Trust (088844/Z/09/Z).

Supplementary Material: Supplementary materials are available on the journal website at http://sdj.sagepub.com/supplemental

References

- 1. Lieber RL, Friden J. Functional and clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle Nerve 2000; 23: 1647–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delp SL, Loan JP, Hoy MG, et al. An interactive graphics-based model of the lower extremity to study orthopaedic surgical procedures. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1990; 37: 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zajac FE. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 1989; 17: 359–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perry J, Burnfield JM. Gait analysis: normal and pathological function. 2nd ed.Thorofare, NJ: Slack Inc, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamel AJ, Sharkey NA, Buczek FL, et al. Relative motions of the tibia, talus, and calcaneus during the stance phase of gait: a cadaver study. Gait Posture 2004; 20: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharkey NA, Hamel AJ. A dynamic cadaver model of the stance phase of gait: performance characteristics and kinetic validation. Clin Biomech 1998; 13: 420–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim KJ, Kitaoka HB, Luo ZP, et al. In vitro simulation of the stance phase in human gait. J Muscoskel Res 2001; 5: 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hurschler C, Emmerich J, Wulker N. In vitro simulation of stance phase gait part I: model verification. Foot Ankle Int 2003; 24: 614–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whittaker EC, Aubin PM, Ledoux WR. Foot bone kinematics as measured in a cadaveric robotic gait simulator. Gait Posture 2011; 33: 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson LT, Aubin PM, Cowley MS, et al. A robotic cadaveric flatfoot analysis of stance phase. J Biomech Eng 2011; 133: 051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delp SL, Anderson FC, Arnold AS, et al. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2007; 54: 1940–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carbone V, Fluit R, Pellikaan P, et al. TLEM 2.0 – a comprehensive musculoskeletal geometry dataset for subject-specific modeling of lower extremity. J Biomech 2015; 48: 734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Modenese L, Phillips AT, Bull AM. An open source lower limb model: hip joint validation. J Biomech 2011; 44: 2185–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maganaris CN, Baltzopoulos V, Sargeant AJ. In vivo measurements of the triceps surae complex architecture in man: implications for muscle function. J Physiol 1998; 512(Pt 2): 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maganaris CN, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T. Changes in aponeurotic dimensions upon muscle shortening: in vivo observations in man. J Anat 2001; 199: 449–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Narici M. Human skeletal muscle architecture studied in vivo by non-invasive imaging techniques: functional significance and applications. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 1999; 9: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Narici MV, Binzoni T, Hiltbrand E, et al. In vivo human gastrocnemius architecture with changing joint angle at rest and during graded isometric contraction. J Physiol 1996; 496(Pt 1): 287–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manal K, Roberts DP, Buchanan TS. Optimal pennation angle of the primary ankle plantar and dorsiflexors: variations with sex, contraction intensity, and limb. J Appl Biomech 2006; 22: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawakami Y, Ichinose Y, Fukunaga T. Architectural and functional features of human triceps surae muscles during contraction. J Appl Physiol 1998; 85: 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomlinson DJ, Erskine RM, Winwood K, et al. The impact of obesity on skeletal muscle architecture in untrained young vs. old women. J Anat 2014; 225: 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lai A, Lichtwark GA, Schache AG, et al. In vivo behavior of the human soleus muscle with increasing walking and running speeds. J Appl Physiol 2015; 118: 1266–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenfeld PF, Dick J, Saxby TS. The response of the flexor digitorum longus and posterior tibial muscles to tendon transfer and calcaneal osteotomy for stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int 2005; 26: 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fukunaga T, Roy RR, Shellock FG, et al. Physiological cross-sectional area of human leg muscles based on magnetic resonance imaging. J Orthop Res 1992; 10: 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friederich JA, Brand RA. Muscle fiber architecture in the human lower limb. J Biomech 1990; 23: 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klein Horsman MD, Koopman HF, van der, Helm FC, et al. Morphological muscle and joint parameters for musculoskeletal modelling of the lower extremity. Clin Biomech 2007; 22: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spoor CW, Van Leeuwen JL, van der Meulen WJ, et al. Active force-length relationship of human lower-leg muscles estimated from morphological data: a comparison of geometric muscle models. Eur J Morphol 1991; 29: 137–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ward SR, Eng CM, Smallwood LH, et al. Are current measurements of lower extremity muscle architecture accurate? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 1074–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wickiewicz TL, Roy RR, Powell PL, et al. Muscle architecture of the human lower limb. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983; 275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Infantolino BW, Challis JH. Short communication: pennation angle variability in human muscle. J Appl Biomech 2014; 30: 663–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laz PJ, Browne M. A review of probabilistic analysis in orthopaedic biomechanics. Proc IMechE, Part H: J Engineering in Medicine 2010; 224: 927–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Standring S. Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 40th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2008, p.xxiv, 1551. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alexander RM, Vernon A. The dimensions of knee and ankle muscles and the forces they exert. J Hum Mov Stud 1975; 1: 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Farahmand F, Senavongse W, Amis AA. Quantitative study of the quadriceps muscles and trochlear groove geometry related to instability of the patellofemoral joint. J Orthop Res 1998; 16: 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thom JM, Morse CI, Birch KM, et al. Influence of muscle architecture on the torque and power-velocity characteristics of young and elderly men. Eur J Appl Physiol 2007; 100: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Handsfield GG, Meyer CH, Hart JM, et al. Relationships of 35 lower limb muscles to height and body mass quantified using MRI. J Biomech 2014; 47: 631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haxton HA. Absolute muscle force in the ankle flexors of man. J Physiol 1944; 103: 267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hartigan JA, Wong MA. Algorithm AS 136: a k-means clustering algorithm. Appl Stat 1979; 28: 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Au C, Dunne J. Gait 2392 and 2354 models. OpenSim Documentation, 2013, http://simtk-confluence.stanford.edu:8080/display/OpenSim/Gait+2392+and+2354+Models (accessed July 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arnold EM, Ward SR, Lieber RL, et al. A model of the lower limb for analysis of human movement. Ann Biomed Eng 2010; 38: 269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Delp SL. Surgery simulation: a computer graphics system to analyze and design musculoskeletal reconstructions of the lower limb. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Valente G, Pitto L, Testi D, et al. Are subject-specific musculoskeletal models robust to the uncertainties in parameter identification? PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e112625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. John CT, Anderson FC, Higginson JS, et al. Stabilisation of walking by intrinsic muscle properties revealed in a three-dimensional muscle-driven simulation. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2013; 16: 451–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. DeMers M. Webinar: estimating joint loads in OpenSim. OpenSim Community, 2011, http://opensim.stanford.edu/support/event_details.html?id=13&;title=Webinar-Estimating-Joint-Loads-in-OpenSim (accessed July 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44. Crowninshield RD, Brand RA. A physiologically based criterion of muscle force prediction in locomotion. J Biomech 1981; 14: 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anderson FC, Pandy MG. Static and dynamic optimization solutions for gait are practically equivalent. J Biomech 2001; 34: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Modenese L, Phillips AT. Prediction of hip contact forces and muscle activations during walking at different speeds. Multibody Syst Dyn 2012; 28: 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thelen DG. Adjustment of muscle mechanics model parameters to simulate dynamic contractions in older adults. J Biomech Eng 2003; 125: 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Steele KM, Demers MS, Schwartz MH, et al. Compressive tibiofemoral force during crouch gait. Gait Posture 2012; 35: 556–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lube J, Cotofana S, Bechmann I, et al. Reference data on muscle volumes of healthy human pelvis and lower extremity muscles: an in vivo magnetic resonance imaging feasibility study. Surg Radiol Anat 2016; 38: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Belavy DL, Miokovic T, Rittweger J, et al. Estimation of changes in volume of individual lower-limb muscles using magnetic resonance imaging (during bed-rest). Physiol Meas 2011; 32: 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Seireg A, Arvikar The prediction of muscular lad sharing and joint forces in the lower extremities during walking. J Biomech 1975; 8: 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stauffer RN, Chao EY, Brewster RC. Force and motion analysis of the normal, diseased, and prosthetic ankle joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977: 127: 189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Procter P, Paul JP. Ankle joint biomechanics. J Biomech 1982; 15: 627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hardt DE. Determining muscle forces in the leg during normal human walking – an application and evaluation of optimization methods. J Biomech Eng 1978; 100: 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Prinold JA, Mazza C, Di Marco R, et al. A patient-specific foot model for the estimate of ankle joint forces in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Biomed Eng 2016; 44: 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brand RA, Pedersen DR, Friederich JA. The sensitivity of muscle force predictions to changes in physiological cross-sectional area. J Biomech 1986; 19: 589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cutts A. Shrinkage of muscle fibres during the fixation of cadaveric tissue. J Anat 1988; 160: 75–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Narici MV, Maganaris CN, Reeves ND, et al. Effect of aging on human muscle architecture. J Appl Physiol 2003; 95: 2229–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morse CI, Thom JM, Birch KM, et al. Changes in triceps surae muscle architecture with sarcopenia. Acta Physiol Scand 2005; 183: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barnouin Y, Butler-Browne G, Voit T, et al. Manual segmentation of individual muscles of the quadriceps femoris using MRI: a reappraisal. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 40: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, et al. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J Appl Physiol 2000; 89: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Lutz KJ, et al. A cross-sectional study of muscle strength and mass in 45- to 78-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol 1991; 71: 644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Modenese L, Ceseracciu E, Reggiani M, et al. Estimation of musculotendon parameters for scaled and subject specific musculoskeletal models using an optimization technique. J Biomech 2016; 49: 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hoy MG, Zajac FE, Gordon ME. A musculoskeletal model of the human lower extremity: the effect of muscle, tendon, and moment arm on the moment-angle relationship of musculotendon actuators at the hip, knee, and ankle. J Biomech 1990; 23: 157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rugg SG, Gregor RJ, Mandelbaum BR, et al. In vivo moment arm calculations at the ankle using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). J Biomech 1990; 23: 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Spoor CW, Van Leeuwen JL, Meskers CG, et al. Estimation of instantaneous moment arms of lower-leg muscles. J Biomech 1990; 23: 1247–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wickiewicz TL, Roy RR, Powell PL, et al. Muscle architecture and force-velocity relationships in humans. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1984; 57: 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pedersen DR, Brand RA, Cheng C, et al. Direct comparison of muscle force predictions using linear and nonlinear programming. J Biomech Eng 1987; 109: 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Patriarco AG, Mann RW, Simon SR, et al. An evaluation of the approaches of optimization models in the prediction of muscle forces during human gait. J Biomech 1981; 14: 513–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Demers MS, Pal S, Delp SL. Changes in tibiofemoral forces due to variations in muscle activity during walking. J Orthop Res 2014; 32: 769–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bergmann G, Deuretzbacher G, Heller M, et al. Hip contact forces and gait patterns from routine activities. J Biomech 2001; 34: 859–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bergmann G. Charite Universitaetsmedizin Berlin ‘OrthoLoad’, 2008, http://www.OrthoLoad.com

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.