Abstract

Background: Graves' ophthalmopathy (GO) pathogenesis involves thyrotropin (TSH) receptor (TSHR)-stimulating autoantibodies. Whether there are autoantibodies that directly stimulate insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors (IGF-1Rs), stimulating insulin-like growth factor receptor antibodies (IGFRAbs), remains controversial. This study attempted to determine whether there are stimulating IGFRAbs in patients with GO.

Methods: Immunoglobulins (Igs) were purified from normal volunteers (NV-Igs) and patients with GO (GO-Igs). The effects of TSH, IGF-1, NV-Igs, and GO-Igs on pAKT and pERK1/2, members of pathways used by IGF-1R and TSHR, were compared in orbital fibroblasts from GO patients (GOFs) and U2OS-TSHR cells overexpressing TSHRs, and U2OS cells that express TSHRs at very low endogenous levels. U2OS-TSHR and U2OS cells were used because GOFs are not easily manipulated using molecular techniques such as transfection, and U2OS cells because they express TSHRs at levels that do not measurably stimulate signaling. Thus, comparing U2OS-TSHR and U2OS cells permits specifically distinguishing signaling mediated by the TSHR and IGF-1R.

Results: In GOFs, all GO-Igs stimulated pERK1/2 formation and 69% stimulated pAKT. In U2OS-TSHR cells, 15% of NV-IGs and 83% of GO-Igs stimulated increases in pERK1/2, whereas all NV-Igs and GO-Igs stimulated increases in pAKT. In U2OS cells, 70% of GO-Igs stimulated small increases in pAKT. Knockdown of IGF-1R caused a 65 ± 6.3% decrease in IGF-1-stimulated pAKT but had no effect on GO-Igs stimulation of pAKT. Thus, GO-Igs contain factor(s) that stimulate pAKT formation. However, this factor(s) does not directly activate IGF-1R.

Conclusions: Based on the findings analyzing these two signaling pathways, it is concluded there is no evidence of stimulating IGFRAbs in GO patients.

Keywords: : Graves' ophthalmopathy immunoglobulins, IGF-1 receptor, TSH receptor, pAKT, pERK1/2

Introduction

The pathogenesis of Graves' ophthalmopathy (GO) is under intense investigation with a goal to develop a medical therapy. Both thyrotropin (TSH) receptors (TSHRs) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptors (IGF-1Rs) appear to be involved in GO pathogenesis (1). Although a consensus has emerged that there are stimulating autoantibodies (TSAbs) that bind to and directly activate TSHRs on cells in orbital connective tissue, it remains controversial whether there are autoantibodies in GO patients that bind to and directly activate IGF-1Rs (stimulating IGFRAbs) (2,3). Another possibility for the involvement of IGF-1Rs in GO pathogenesis, which the authors favor, is that IGF-1R activation results not from IGFRAbs but from cross-talk with TSHRs activated by TSAbs (4). The authors of three previous reports came to different conclusions regarding the presence (5) or absence (4,6) of stimulating IGFRAbs in the serum of patients with GO. Of note, the primary readout for stimulating IGF-1RAb activity was the same in all three studies: namely, IGF-1R auto-phosphorylation (formation of pIGF-1R), which is a major initiator of IGF-1R signaling. In one study (5), Varewijck et al. reported that some GO serum specimens caused a small increase in pIGF-1R that was decreased after immunoglobulin depletion. These authors suggested that in “a subset of patients with GO, [immunoglobulins] may have IGF-1R stimulating activities.” In the two other studies by Minich et al. (6) and Krieger et al. (4), the authors concluded that there was no evidence for immunoglobulins in GO blood causing increases in pIGF-1R, specifically that any small increases in pIGF-1R levels caused by immunoglobulins from GO patients (GO-Igs) were the same as those found with immunoglobulin preparations from healthy volunteers (NV-Igs).

It is now appreciated that IGF-1R can activate signaling cascades in the absence of demonstrable increases in pIGF-1R (7). It was therefore thought to be important to use another readout of IGF-1R activation to determine whether IGFRAbs are present in the serum of GO patients. It was recently shown that TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk occurs at a proximal step in the TSHR signaling cascade by measuring activation/phosphorylation of mitogen-activated kinases 1 and 3 (extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2 [ERK1/2]), that is, formation of pERK1/2 (8). In contrast, IGF-1 alone causes a smaller increase in the level of pERK1/2 than activation of TSHRs but robustly stimulates activation/phosphorylation of AKT serine/threonine kinase, that is, formation of pAKT, which is a major step in signal transduction by IGF-1R in many cells/tissues (9,10). This study compared the effects of stimulation by NV-Igs and GO-Igs on pAKT and pERK1/2. These effects were studied in orbital fibroblasts from patients with severe GO (GOFs) (11), which are the putative in vivo targets of circulating autoantibodies in GO pathogenesis. U2OS-TSHR cells were also studied, a pre-osteoblastic line that was engineered to express TSHRs (12), and U2OS cells that endogenously express TSHRs at very low levels because GOF cells are not easily manipulated using molecular techniques such as transfection. Specifically, U2OS-TSHR cells were used, since they had been used previously to study TSHR signaling, and U2OS cells that express high levels of IGF-1R but functional TSHRs at very low levels such that TSH had no effect on pAKT levels. Thus, in U2OS cells, any effects of GO-Igs on pAKT formation would be mediated by a receptor(s) other than TSHR, such as IGF-1R.

No preparation of GO-Igs was found that stimulated pAKT formation in a IGF-1R-dependent manner. Therefore, based on the findings with this pathway, it is concluded there is no evidence of stimulating IGFRAbs in GO patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients and study approval

A total of 63 serum samples from patients with phenotypically overt and clinically severe and active GO, according to the joint European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves' Ophthalmopathy guidelines for the management of GO (11), were collected at the joint thyroid eye clinic of the Johannes Gutenberg University Medical Center, Mainz, Germany. The collection of patients' serum samples was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Chamber of the State Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, and by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Johannes Gutenberg University Medical Center. Written informed consent was received from all patients with GO prior to blood withdrawal. Six patients with clinically active GO (GO Bethesda [GOB]1, GOB8, GOB9, GOB10, GOB12, and GOB13) and one patient with a history of exposure keratopathy associated with lid retraction (GOB11) were identified out of a cohort of patients with GD at the Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Obesity Branch of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Blood samples from these patients (clinical trial identifier: NCT00001159) and 20 samples from healthy volunteers were obtained. Samples from euthyroid healthy volunteers (NCT00428987) were obtained under NIDDK/NIAMS IRB approved protocols after informed consent was obtained.

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 100-fold penicillin-streptomycin solution, L-glutamine, Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture, 1 M HEPES buffer, and Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) were obtained from Mediatech, Inc. (Manassas, VA). Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Bovine TSH and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Hygromycin was from purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. (Carlsbad CA). Recombinant human IGF-1 was purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Lysis Buffer 6 (catalog # 895561), Phospho-ERK1 (T202/Y204)/ERK2 (T185/Y187) DuoSet IC enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Phospho-Akt (S473) Pan Specific DuoSet IC ELISA kits, DuoSet Ancillary Reagent Kit 2 (#DY008), and Sample Diluent Concentrate 1 (DYC001) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). PhosSTOP (#04906837001) and cOmplete (04693132001) were purchased from Roche (Nutley, NJ). A Spin-X UF Concentrator with Tube-O-Dialyzer was purchased from G-Biosciences (#786-619; St. Louis, MO). ON-TARGETplus SMART pool human IGF-1R siRNA (#T-2001-03-00), ON-TARGET plus non-targeting pool siRNA (#D-001810-10), and DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (#T-2001-03) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Total rabbit anti-IGF-1 receptor beta (#3027S) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA).

Cell culture

GOFs were obtained and cultured as previously described (8). In brief, orbital connective tissue was obtained from GO patients who underwent orbital decompression surgery. Informed consent was obtained from patients prior to inclusion in these studies. Use of human tissues was approved by the Johannes Gutenberg University (JGU) Medical Center and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases IRBs. Tissue explants were minced and plated in culture dishes. Resulting monolayer outgrowths of adherent cells were serially passaged with trypsin/EDTA. Cells were maintained in a humidified 7% CO2 incubator at 37°C. All experiments were performed at passage 4 or below.

The generation of a U2OS cell line stably expressing TSHRs (U2OS-TSHR) has been described previously (10). U2OS-TSHR and U2OS cells were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 IU/mL of penicillin, and 50 μg/mL of streptomycin. U2OS-TSHR cells were maintained in medium containing 250 μg/mL of hygromycin for continued selection. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Experiments were performed in serum-free conditions: FBS was replaced with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) 24 h prior to experiments.

Knockdown of IGF-1R in U2OS cells

U2OS cells were seeded in EMEM with 10% FBS into 100 mm dishes at 1.75 × 106 cells per dish. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with ON-TARGET plus SMART pool human IGF-1R siRNA or ON-TARGET plus non-targeting pool siRNA using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were seeded into 24-well plates at 55,000 cells/cm2 and incubated for 48 h. Cells were arrested in EMEM containing 0.1% BSA overnight and then were stimulated for Akt phosphorylation at 96 h post transfection. Knockdown efficiency was assessed by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction and Western blot.

Purification of Igs from whole serum

Igs were isolated from whole serum by thiophilic affinity chromatography, as previously described (4). In brief, a 2 mL gravity flow column was packed with Thiophillic-Superflow resin and equilibrated according to the manufacturer's directions. Samples were diluted 1:10 in sample buffer (50 mM of sodium phosphate, 0.55 M of sodium sulfate, pH 7.0) and applied to the column, and unbound proteins were washed away with 50 mM of sodium phosphate, 0.5 M of sodium sulfate, pH 7.0. Igs were eluted with two to three column volumes of 20 mM sodium phosphate, 20% glycerol, pH 7.0. Eluent samples were combined and concentrated to their original volume using a Spin-X UF Concentrator, and then dialyzed with Tube-O-Dialyzer in HBSS containing 10 mM of HEPES, pH 7.4. Final protein concentration was measured with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay.

Measurement of pERK1/2 and pAKT by ELISA

GOFs were plated at 180,000 cells/cm2, stepped down in serum-free 0.1% BSA-containing DMEM for 4–24 h, and then treated with TSH (100 mIU/mL), IGF-1 (100 ng/mL), or GO-Igs (diluted 1:5) for 10 min at 37°C. Following stimulation, cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS containing 10 mM of HEPES and then lysed and assayed for pERK1/2 and pAKT by ELISA according to the manufacturer's directions.

U2OS-TSHR or U2OS cells were plated at 55,000 cells/cm2 in EMEM containing 10% FBS. Four to 24 h prior to the experiment, the media were changed to serum-free 0.1% BSA-containing EMEM. At the start of the experiment, cells were treated with TSH, IGF-1, NV-Igs, or GO-Igs as above for 5 min at 37°C in a water bath. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS/HEPES. Cell lysates were prepared with Lysis Buffer 6 containing 1 × phosSTOP and 1 × cOmplete. pERK1/2 and pAKT were assayed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Because the lysate of U2OS-TSHR cells depressed the absorbance in the pAKT assay, an equal volume of cell lysate from cells in which no pAKT was detectable was added in the pAKT standard curve. The lysate of U2OS-TSHR cells did not depress the absorbance in the pERK1/2 assay, and therefore, the standard curve was generated in buffer alone. The values are reported as pg/well or %IGF-1 stimulation to normalize for variations in the absolute levels of pAKT or pERK1/2 in different experiments.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism for Windows v7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) by t-test. p-Values <0.05 were considered significant between levels.

Results

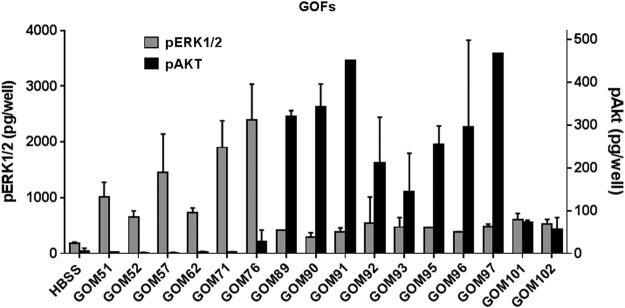

As previously published in GOFs (8,13), TSHR activation provokes a large increase in pERK1/2, whereas IGF-1R activation provokes a large increase in pAKT. Figure 1 illustrates that in GOFs, all GO-Igs stimulated increases in pERK1/2, and 69% of GO-Igs increased pAKT. There was, however, a wide variation in the levels of the increases caused by different GO-Igs, and there was no correlation in stimulation of pERK1/2 and pAKT. Moreover, some GO-Igs stimulated increases in both phosphokinases, and others stimulated an increase in one but not the other.

FIG. 1.

Graves' ophthalmopathy (GO) immunoglobulins (GO-Igs) stimulation of pERK1/2 and pAKT formation in GO orbital fibroblast (GOF) cells. GOF cells were incubated in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; Basal) or stimulated by GO-Igs (diluted 1:5), as described in Materials and Methods. GOM stands for patient samples from Mainz, Germany. pERK1/2 levels (gray bars) and pAKT levels (black bars) were plotted as pg/well (M ± SD) in two experiments.

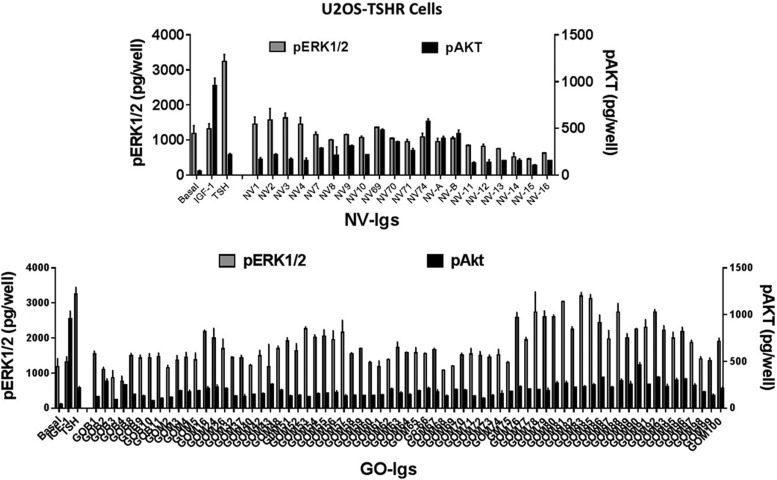

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of IGF-1, TSH, NV-Igs, and GO-Igs on pERK1/2 and pAKT formation in U2OS-TSHR cells. As expected, IGF-1 caused a small increase in pERK1/2 but stimulated a robust increase in pAKT, whereas TSH caused a robust increase in pERK1/2 but only a small increase in pAKT. NV-Igs and GO-Igs exhibited variable responses. In U2OS-TSHR cells, 15% of NV-Igs and 83% of GO-Igs stimulated increases in pERK1/2, whereas all NV-Igs and GO-Igs stimulated increases in pAKT. In fact, five of the six highest pAKT levels were observed in U2OS-TSHR cells stimulated by NV-Igs.

FIG. 2.

Effects of Igs purified from normal volunteers (NV-Igs) and GO patients (GO-Igs) on the levels of pERK1/2 and pAKT in U2OS-TSHR cells. U2OS-TSHR cells were incubated in HBSS (Basal) or stimulated by 100 ng/mL of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), 100 mIU/mL of thyrotropin (TSH), 1:5 diluted NV-Igs (NV#), or 1:5 diluted GO-Igs (GOB# or GOM#), as described in the Materials and Methods. GOB and GOM stand for patient samples from Bethesda, MD, and Mainz, Germany, respectively. pERK1/2 levels (gray bars) and pAKT levels (black bars) were plotted as pg/well (M ± SD) in three experiments.

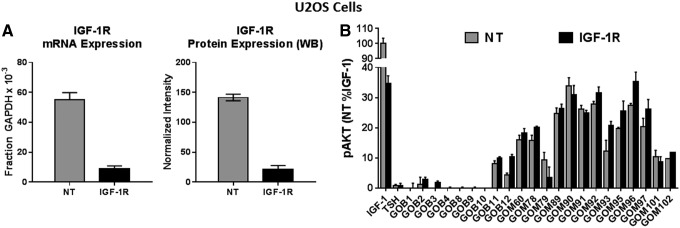

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of IGF-1 and GO-Igs on pAKT formation in U2OS cells in which functional activity of TSHR is undetectable under these conditions. IGF-1 caused a robust increase in pAKT in U2OS cells. It was possible to study some of the GO-Igs that stimulated more robust increases in pERK1/2 and pAKT in U2OS-TSHR cells. Seventy percent of GO-Igs stimulated increases in pAKT in U2OS cells.

FIG. 3.

Effects of GO-Igs on the levels of pAKT in U2OS cells. U2OS cells were incubated in HBSS or stimulated by 100 ng/mL of IGF-1 or 1:5 diluted GO-Igs (GOB# or GOM#), as described in the Materials and Methods. GOB and GOM stand for patient samples from Bethesda, MD, and Mainz, Germany, respectively. pAKT levels were plotted as %IGF-1 effect after subtracting basal pAKT (M ± SD) in five experiments.

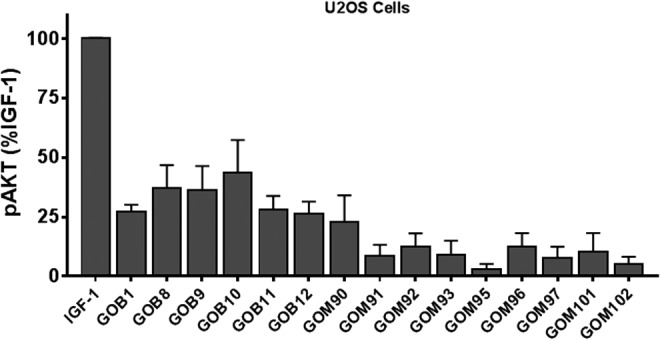

To determine definitively whether IGF-1R is activated by GO-Igs to increase pAKT, IGF-1R was knocked down. Figure 4 illustrates the effect of knocking down IGF-1Rs in U2OS cells. IGF-1R mRNA and protein levels in siRNA-treated cells were 16% of those in controls (Fig. 4A). The non-targeting (NT) controls represent cells that were transfected with NT siRNA. As expected, IGF-1 stimulated a robust increase in the level of pAKT, and that response was decreased by 65 ± 6.3% in cells transfected with IGF-1R siRNA (Fig. 4B). TSH had no effect on pAKT. Notably, IGF-1R knockdown did not decrease stimulation of pAKT formation by GO-Igs.

FIG. 4.

Effect of knockdown of IGF-1R on GO-Igs stimulation of pAKT formation in U2OS cells. siRNA was used to knockdown IGF-1R levels in U2OS cells, as described in the Materials and Methods. Control cells, transfected with non-targeting siRNA (NT), and cells in which IGF-1R was decreased by transfection with IGF-1R siRNA (IGF-1R) were incubated in HBSS or stimulated by 100 ng/mL of IGF-1, 100 mIU/mL of TSH, or 1:9 diluted GO-Igs (GOB# and GOM#), as described in Materials and Methods. GOB and GOM stand for patient samples from Bethesda, MD, and Mainz, Germany, respectively. (A) mRNA and protein levels of IGF-1R in NT (gray bars) and IGF-1R siRNA-treated cells (black bars). WB, Western blot. (B) pAKT levels in NT cells (gray bars) and pAKT levels in IGF-1R knockdown cells (black bars) were plotted as %IGF-1 effect in NT cells (M ± SD) in three experiments.

Discussion

This study used the formation of pAKT, which is a major mediator of IGF-1R signaling in many cell types (9), as the readout for IGF-1R activation and knockdown of IGF-1R by siRNA to probe whether GO-Igs directly bind and activate IGF-1Rs. Evidence was previously provided that involvement of IGF-1Rs in GO-Ig and TSH stimulation of signaling is caused by TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk, not by direct activation of IGF-1Rs (4). Here, it is shown that GO-Igs and NV-Igs stimulate pAKT formation in all three cell types studied: GOFs, U2OS-TSHR cells, and U2OS cells. However, in GOFs and U2OS-TSHR cells, this may be mediated by TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk. Thus, only in U2OS cells could TSHR-independent signaling be assessed. In U2OS cells, GO-Igs still stimulated pAKT formation (Figs. 3 and 4). Importantly, however, knocking down IGF-1Rs in U2OS cells, as expected, inhibited IGF-1 stimulation of pAKT formation but had no effect on GO-Igs stimulation of pAKT formation. Thus, GO-Igs contain a factor(s) that stimulates pAKT formation. However, this factor(s) can act independently of TSHR but does not act by directly activating IGF-1R.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, an IGFRAb, identification of which it is suggested requires studying monoclonal antibodies, not preparations of GO-Igs that contain many antibodies, has not been found in any human disease. Monoclonal anti-IGF-1R antibodies that inhibit IGF-1 binding to and IGF-1 activation of IGF-1R (14) have been generated in animals, and these antibodies have been shown to downregulate IGF-1R levels, leading to decreased IGF-1R signaling (15,16). It has been found that inhibitory anti-IGF-1R antibodies downregulate IGF-1Rs in GOFs and U2OS-TSHR cells (unpublished observations). Antibodies that bind to IGF-1R have been found in the serums of GO patients, but these appear to be inhibitory antibodies (6,17). Lastly, it is thought that a stimulatory IGFRAb would have widespread effects throughout the body, since many cells/tissues express IGF-1Rs. However, GO patients do not exhibit changes, such as tissue hypertrophy/hyperplasia or tumor formation, which would be consistent with persistent IGF-1R stimulation. Thus, taken together, these findings are consistent with the concept that there are no stimulating IGFRAbs in GO-Ig preparations.

In conclusion, no evidence was found for stimulating IGFRAbs in sera from patients with GO by monitoring the pAKT signaling pathway. Of note, the previous finding that a monoclonal TSAb is capable of stimulating TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk by binding only to TSHRs (18) shows that direct activation of IGF-1R by an antibody is not needed to explain the involvement of IGF-1R in GO pathogenesis. Therefore, it is suggested that the recent success in a clinical trial using an anti-IGF-1R antibody (19) is not because this antibody blocks direct activation of IGF-1Rs by GO-Igs, that is, by stimulating IGFRAbs, but because it can interfere with TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk initiated by GO-Igs that bind to and activate TSHRs (4).

Acknowledgments

We thank Tanja Diana, PhD, MSc, and Michael Kanitz, Thyroid Lab, JGU Medical Center, Mainz, Germany, for the preparation of the collected orbital tissue and serum samples from patients with severe and active GO. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, 1 Z01 DK011006.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Smith TJ, Janssen JA. 2016. Building the case for insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 involvement in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 7:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith TJ, Janssen JAMJL. 2017. Response to Krieger et al. re: TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk, not IGF-1R stimulating antibodies, mediates Graves' ophthalmopathy pathogenesis (Thyroid 27:746–747). Thyroid 27:1458–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann S, Gershengorn MC. 2017. Rebuttal to Smith and Janssen (Thyroid 2017; 27:1458–1459). Thyroid 27:1459–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krieger CC, Place RF, Bevilacqua C, Marcus-Samuels B, Abel BS, Skarulis MC, Kahaly GJ, Neumann S, Gershengorn MC. 2016. TSH/IGF-1 receptor cross talk in Graves' ophthalmopathy pathogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101:2340–2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varewijck AJ, Boelen A, Lamberts SW, Fliers E, Hofland LJ, Wiersinga WM, Janssen JA. 2013. Circulating IgGs may modulate IGF-I receptor stimulating activity in a subset of patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minich WB, Dehina N, Welsink T, Schwiebert C, Morgenthaler NG, Kohrle J, Eckstein A, Schomburg L. 2013. Autoantibodies to the IGF1 receptor in Graves' ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:752–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girnita L, Worrall C, Takahashi S, Seregard S, Girnita A. 2014. Something old, something new and something borrowed: emerging paradigm of insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor (IGF-1R) signaling regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:2403–2427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger CC, Perry JD, Morgan SJ, Kahaly GJ, Gershengorn MC. 2017. TSH/IGF-1 receptor cross-talk rapidly activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases in multiple cell types. Endocrinology 158:3676–3683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler AA, Yakar S, Gewolb IH, Karas M, Okubo Y, LeRoith D. 1998. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signal transduction: at the interface between physiology and cell biology. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 121:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutin A, Neumann S, Gershengorn MC. 2016. Multiple transduction pathways mediate thyrotropin receptor signaling in preosteoblast-like cells. Endocrinology 157:2173–2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Boboridis K, Eckstein A, Kahaly GJ, Marcocci C, Perros P, Salvi M, Wiersinga WM. on behalf of the European Group on Graves' Ophthalmopathy (EUGOGO) 2016. The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves' Ophthalmopathy guidelines for the management of Graves' ophthalmopathy. Eur Thyroid J 6:9–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutin A, Eliseeva E, Gershengorn MC, Neumann S. 2014. β-Arrestin-1 mediates thyrotropin-enhanced osteoblast differentiation. FASEB J 28:3446–3455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S, Nadeem S, Stan MN, Coenen M, Bahn RS. 2011. A stimulatory TSH receptor antibody enhances adipogenesis via phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation in orbital preadipocytes from patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. J Mol Endocrinol 46:155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S-L, Kato J, Paz B, Kasuya J, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y. 1993. Two new monoclonal antibodies against the human insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 196:92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hailey J, Maxwell E, Koukouras K, Bishop WR, Pachter JA, Wang Y. 2002. Neutralizing anti-insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 antibodies inhibit receptor function and induce receptor degradation in tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther 1:1349–1353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohtani M, Numazaki M, Yajima Y, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y. 2009. Mechanisms of antibody-mediated insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) down-regulation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biosci Trends 3:131–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weightman DR, Perros P, Sherif IH, Kendall-Taylor P. 1993. Autoantibodies to IGF-1 binding sites in thyroid associated opthalmopathy. Autoimmunity 16:251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger CC, Neumann S, Marcus-Samuels B, Gershengorn MC. 2017. TSHR/IGF-1R cross-talk, not IGF-1R stimulating antibodies, mediates Graves' ophthalmopathy pathogenesis. Thyroid 27:746–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith TJ, Kahaly GJ, Ezra DG, Fleming JC, Dailey RA, Tang RA, Harris GJ, Antonelli A, Salvi M, Goldberg RA, Gigantelli JW, Couch SM, Shriver EM, Hayek BR, Hink EM, Woodward RM, Gabriel K, Magni G, Douglas RS. 2017. Teprotumumab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 376:1748–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]