Abstract

Developmental lead (Pb) exposure results in persistent cognitive/behavioral impairments as well as an elevated risk for developing a variety of diseases in later life. Environmental exposures during development can result in a variety of epigenetic changes, including alterations in DNA methylation, that can influence gene expression patterns and affect the function and development of the nervous system. The present promoter-based methylation microarray profiling study explored the extent to which developmental Pb exposure may modify the methylome of a brain region, hippocampus, known to be sensitive to the effects of Pb exposure. Male and female Long Evans rats were exposed to 0 ppm, 150 ppm, 375 ppm, or 750 ppm Pb through perinatal exposures (gestation through lactation), early postnatal exposures (birth through weaning), or long-term postnatal exposures (birth through postnatal day 55). Results showed a significant contribution of sex to the hippocampal methylome and effects of Pb exposure level, with nonlinear dose response effects on methylation. Surprisingly, the developmental period of exposure contributed only a small amount of variance to the overall data and gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed the largest number of overrepresented GO terms in the groups with the lowest level of exposure. The highest number of significant differentially methylated regions was found in females exposed to Pb at the lowest exposure level. Our data reinforce the significant effect that low level Pb exposure may have on gene-specific DNA methylation patterns in brain and that this occurs in a sex-dependent manner.

Keywords: lead toxicity, hippocampus, brain, DNA methylation, developmental exposure, sex, heavy metal, epigenetics

1. Introduction

Exposure to lead (Pb) during development leads to cognitive and behavioral disturbances that persist into adulthood (Canfield et al., 2003; Lanphear et al., 2005; Lidsky and Schneider, 2003; Needleman et al., 1990; Reuben et al., 2017) and is associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes later in life (Hernberg, 2000; Spivey, 2007). Recognizing the serious negative impact Pb exposure has on neurobehavioral development, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 1991, set the “level of concern” for Pb exposure in children to a blood Pb level (BLL) of 10 µg/dL (CDC, 1991). In the decades since, a large amount of data from clinical, epidemiological, and basic science studies have shown that adverse neurodevelopmental effects from exposure to Pb occur at BLLs considerably lower than 10 µg/dL. Based on the accumulation of compelling evidence showing negative cognitive, neurobehavioral, and academic achievement outcomes in children exposed to very low levels of Pb, the CDC’s Advisory Committee for Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention (ACCLPP) recommended in 2012 that the term “level of concern” be abandoned and instead, suggested that a reference value based on the 97.5th percentile of the BLL distribution among children 1–5 years old in the United States (i.e., 5 µg/dL) be used to identify children with elevated BLLs (ACCLPP, 2012). It is now generally accepted that there may be no safe level of Pb in the blood of a child (CDC, 1991; ACCLPP, 2012).

Persistent effects from developmental Pb exposure suggest an early-life basis of adult disability in which insults that occur early in life produce changes that arise from physiological reprogramming (Cottrell and Seckl, 2009). One way in which this might occur is through epigenetic modification of the genome. Epigenetics refers to molecular modifications of DNA that switch genes on and off based on molecular modifications to DNA without a change in the DNA sequence (Jirtle and Skinner, 2007). These include modifications in DNA methylation at the carbon-5 position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides and changes to the chromatin packaging of DNA by post-translational histone modifications such as acetylation and methylation (Jirtle and Skinner, 2007), as well as modifications induced by miRNA. Such epigenetic changes are a normal part of gene regulation but when aberrantly modified can incorrectly silence or activate a gene (or genes), influencing cell health and functionality. Early occurring epigenetic changes in response to certain environmental factors can even be inherited transgenerationally, potentially affecting the health of future generations (Jirtle and Skinner, 2007).

Epidemiological data have linked peripheral DNA methylation levels to markers of cumulative Pb exposure (Pilsner et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2010). These studies reported Pb-induced changes in broad genomic DNA methylation marks such as LINE-1 (long-interspersed nuclear elements-1) and Alu (the most abundant repetitive elements in the human genome: Alu elements are considered as regulators of gene expression), measured in leukocytes, as surrogate measures for estimating global DNA methylation levels. However, methylation levels of these repetitive elements may not be equivalent to global DNA methylation content and the mechanisms that control methylation of these repetitive elements may differ from those that influence the rest of the genome (Vryer and Saffery, 2017). Thus, while measuring peripheral Alu and LINE-1 methylation levels is informative, it may not necessarily provide an accurate representation of total genome-wide methylation, particularly in the brain.

Sex differences in the response to a variety of neurotoxicants is now fairly well established in basic science studies but has received comparatively little attention in epidemiological studies. In many clinical studies of the effects of Pb on the neurodevelopment of children, data from males and females have often not been analyzed separately. In those studies where sex effects were examined, results have varied depending on level of exposure, age of the children, age at testing and measures of cumulative or concurrent exposures. Yet, more often than not, negative outcomes from developmental Pb exposures have been described more frequently in males than in females (see Llop, 2013 for review). In contrast to the clinical literature, an abundance of basic science findings show clear sex-dependent effects of developmental Pb exposure on the brain and behavior (ex., Anderson et al., 2016). Recent animal studies have also suggested that sex is a factor in the epigenetic response to Pb exposure (Faulk et al., 2013; Sanchez-Martin et al., 2015; Schneider et al., 2016; Varma et al., 2017) and that effects may be different in different brain regions (Sanchez-Martin et al., 2015; Schneider et al., 2016; Varma et al., 2017).

Considering the potential impact that Pb exposure may have on epigenetic responses in the brain and on DNA methylation in particular, the present study was conducted to investigate the extent to which the factors of sex, Pb exposure level and developmental timing/duration of exposure contribute to and influence genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in the hippocampus, a brain region previously shown to be particularly sensitive to developmental Pb exposure (Liu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016).

2. Methods

2.1 Animals and experimental design

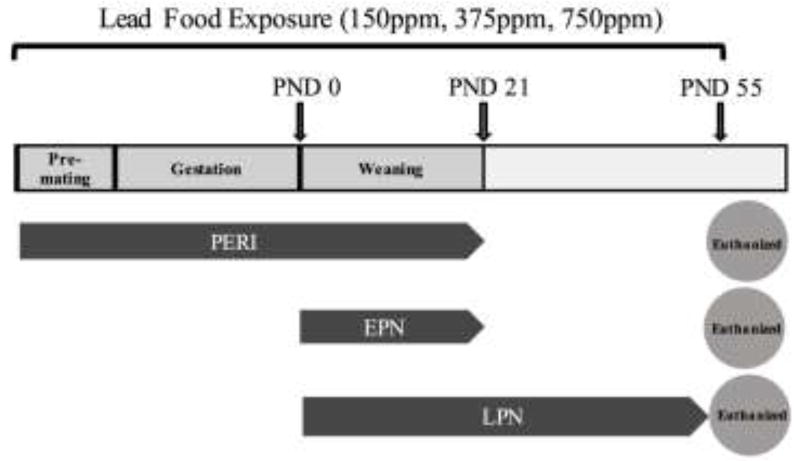

The use of animals was in compliance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the study was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Thomas Jefferson University. Male and female Long-Evans rats were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, USA) for breeding. A total of ten experimental groups of dams were generated across different Pb exposure paradigms (Figure 1). Three Pb exposure paradigms were used: perinatal (PERI), early postnatal (EPN), and long-term postnatal (LPN) exposures. In the PERI group, dams were fed chow (RMH 1000) with or without added Pb acetate (inorganic Pb) (0 ppm, 150 ppm (150mg Pb/kg chow), 375 ppm (375mg Pb/kg chow) or 750 ppm (750mg Pb/kg chow)) for ten days prior to breeding and remained on the same diet through weaning. Pups were exposed to Pb from gestation through lactation (i.e., to postnatal day 21) and at weaning, rats were housed four to a standard cage (940 cm2) with ad lib access to chow (no added Pb) and water until euthanized at postnatal day 55. For animals in the EPN group, dams were fed RMH 1000 chow with no added Pb during gestation and were fed chow with or without added Pb acetate beginning at parturition and pups continued to receive the same Pb exposure through weaning at postnatal day 21. The LPN group received Pb exposure similar to the EPN group but exposure continued to postnatal day 55. Female rats were mated with males (1:1) for 4 to 5 days to cover the duration of an estrous cycle. All litters were culled to equal numbers of pups to standardize litter size at postnatal day 7, with an aim of having eight pups per litter. No more than 1 pup/sex/dam/treatment group was used to preclude litter specific effects. All animals were exposed to a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle for the duration of the experiment. Blood samples were collected at the time of euthanasia and analyzed for Pb levels by graphite furnace atomic absorption with Zeeman background correction (ESA Labs, MA).

Figure 1. Experimental design.

Animals were exposed to 150 ppm, 375 ppm and 750 ppm lead (Pb) in food during different exposure periods: PERI (perinatal: dams exposed to Pb 10 days before breeding and continued through weaning (PND21)), EPN (early postnatal: dams were exposed to Pb at the time of parturition (PND0) and continued through weaning (PND21)), and LPN (long-term postnatal: Pb exposure started at the time of parturition (PND0) and continued through PND55). All pups were euthanized at PND55.

2.2 Tissue processing, DNA extraction, MeDIP and whole genome amplification

Animals were euthanized on postnatal day 55 by rapid decapitation and whole dorsal hippocampi were rapidly removed, flash frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until processed. Genomic DNA was extracted from tissue samples from 12 animals/group (6 male/6 female) using PureGene DNA isolation kits (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to manufacturer instructions. DNA quality was assessed using Agilent Bioanalyzer Chips (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) was performed using Diagenode IP-Star as per manufacturer instructions. qPCR was performed using spiked methylated DNA primers as well as TSH2B (genomic positive control for MeDIP) and Gapdh (genomic negative control for MeDIP) to check enriched methylated DNA. Immunoprecipitated DNA from MeDIP was amplified with a whole genome amplification (WGA) kit, (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) using one round of WGA with 18 cycles of amplification. Quality control for unbiased amplification was accomplished by qPCR using TSH2B and Gapdh primers.

2.3 DNA labeling and array hybridization

DNA labeling and hybridization were performed according to NimbleGen’s protocol with modifications. The immunoprecipitated CpG-methylated DNA (test, experimental samples) and the untreated, sonicated DNA (input DNA) were differentially labeled and hybridized to a single array as a two-color experiment (Rat DNA Methylation 3 × 720 K CpG Island Plus RefSeq Promoter Array (GPL 18610) for 20 h at 42°C, followed by washing with the Nimblegen Wash Kit. Pairs of samples intended for hybridization to the same array were labeled in parallel using Cy3 Random and Cy5 Random Nonamers from the same kit (or multiple kits from the same lot). Experimental (IP) samples were labeled with Cy5 and control (input) samples with Cy3. The promoter array had tiling of each RefSeq gene promoter starting 3.9kb upstream of the transcription start site and extending downstream 0.97kb for a total of 4.87kb of promoter coverage per gene.

2.4 Array scanning, data processing, and data analysis

Scanning was performed with 100% gain and double pass for optimal sensitivity and scanning accuracy. Raw data were extracted as pair files by NimbleScan software. The intensity ratio of immunoprecipitated to control DNA was plotted versus genomic position to identify regions where increased signal (i.e. DNA fragment enrichment) was present relative to the control sample.

The R/Bioconductor package Ringo was utilized to extract the green (Cy3, 532nm, associated to total DNA) and red (Cy5, 635nm, associated to MeDIP fraction) channels from the provided pair files. Normalization of the probe intensities was carried out by applying the Nimblegen algorithm, following the recommendation of Adriaens et al. for ChIP-on-chip and DNA methylation microarrays (Adriaens et al., 2012). Signals from the two channels were then summarized by calculating the log2 ratio of the MeDIP and input channels. Being log2-ratios, a value of 1 corresponds to a two-fold enrichment of the MeDIP signal relative to total DNA, while a value of −1 is interpreted as a MeDIP signal two times smaller than the input channel.

2.5 Differential Methylation Analysis and Gene Ontology

Probe-wise differential methylation analysis between experimental groups was performed using the Limma Bioconductor package. Specifically, a linear model using the Group variable was fit to each probe and various linear combinations of coefficients in the model were tested for statistical significance. To detect differentially methylated regions, each tiled region was tested for over-representation in the list of significant probes for a given comparison, using Fisher’s exact test as implemented in the GOseq package. The probe-level cutoff used for this analysis was P<0.01 and |FC|>1.5 at 0.25 FDR (FC=fold change and FDR=false discovery rate). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed with the hypergeometric test of the GOseq package (Geeleher et al., 2013). For each comparison group only significantly overrepresented biological functions (P< 0.05), composed of a minimum of 5 genes, were taken into account.

2.6 qPCR Analysis

RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit and reverse transcription was performed with Omniscript RT Kits (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All gene specific primer assays, validated for qPCR, were purchased from Qiagen SABioscience (Cat No.- Gapdh: PPR06557B, Trhde: PPR57413A, Fabp4: PPR43395F, Pmepa1: PPR56628B, Dync1li1: PPR42659A, Hrh4: PPR52242A, Golph3: PPR51529A, Cgref1: PPR48465A and Crabp1: PPR43001A. Quantitative real time PCR was performed on cDNA in the presence of SYBR Green reagent (Roche, Pleasanton, CA) using the Roche LightCycler 480. PCR data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method to calculate fold change of mRNA expression. Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism v7) was used to determine statistical difference between samples (Pb-exposed vs no Pb-control).

3. Results

Blood lead levels measured at PND 55 (at euthanasia) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Blood lead levels (mean ± SEM)

| Blood lead levels (µg/dl) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 150ppm | 375ppm | 750ppm | |||||||

| PERI | EPN | LPN | PERI | EPN | LPN | PERI | EPN | LPN | ||

| FEMALE | <1.00 | 1.36±0.15 | 2.11±0.39 | 4.50±0.65 | 2.13±0.13 | 2.00±0.21 | 5.75±048 | 2.08±0.14 | 3.09±0.21 | 9.58±0.62 |

| MALE | <1.00 | 1.25±0.25 | 1.64±0.25 | 2.00±0.00 | 2.42±0.38 | 1.95±0.24 | 8.00±0.00 | 2.47±0.17 | 2.83±0.21 | 7.46±0.38 |

PERI = perinatal exposure; EPN = early postnatal exposure; LPN = long-term postnatal exposure. PERI and EPN groups were exposed to Pb through postnatal day 21 while LPN Pb exposure lasted through postnatal day 55.

3.1 Redundancy Analysis: Effect of sex, exposure level and developmental timing of exposure

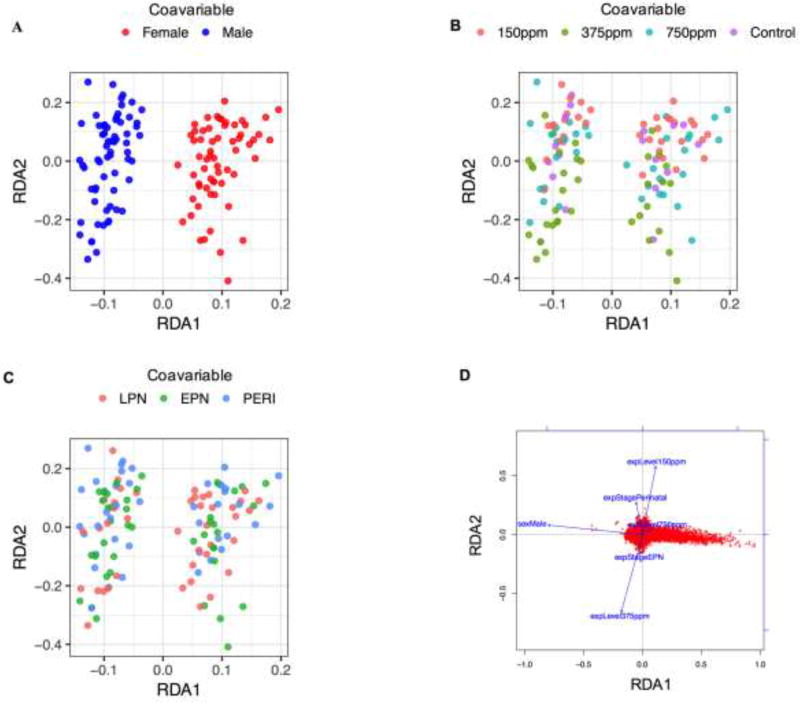

As a first step to investigate the effect of different Pb exposures and levels in males and females, redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed on the microarray data to present a global view of the hippocampal methylome in relation to the experimental conditions. RDA analysis allowed us to understand the relationships between the principal components and the experimental factors (sex, exposure level and stage) while focusing on the origin of variance. The main effect contributing to the variance in the methylation data was sex, with a stronger effect of sex on the variance of methylation data compared to exposure level or period of exposure (Fig. 2A–C). A small effect of exposure level was seen, and interestingly, 150ppm and 375ppm exposures had opposite effects on DNA methylation levels (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. RDA analysis.

(A–D) RDA plots for the covariable sex (A), Pb exposure level (B) and developmental period of exposure (C) are shown depicting a global view of the relationships between the methylation profiles and experimental conditions. Each colored dot represents a probe. RDA analysis showed that compared to exposure level and developmental period of exposure, sex was the major driver of the observed methylation changes in the hippocampus. The sex covariable is strongly associated with the RDA1 axis but exposure levels and exposure periods are not clearly associated with the RDA2 axis. In the RDA plot (D), each red dot represents a probe and the blue arrows represent covariables. This plot shows that the sex effect is associated with the RDA1 axis (sex effect) and exposure levels (150ppm and 375ppm) are associated with the RDA2 axis (exposure level effect). The two exposure levels were found to be anti-correlated (i.e., effects in opposite directions). The length of the arrow reflects the size of the effect of the covariable.

3.2 Differential methylation analysis after Pb exposure

Probe-wise differential methylation analysis between experimental groups was performed using the Limma Bioconductor package, with probe-level cutoff at p<0.01 and |FC|>1.5 at 0.25 FDR. The number of significant probes (each corresponding to a gene) identified in each experimental group compared to control group are shown in Table 2 (also see Fig.S3). In females, the highest number of significant differentially methylated genes were found in the 150ppm LPN group (1,770 genes) and in the 375ppm PERI group (255 genes), with minimal differentially methylated genes detected in the other groups. In males, the highest numbers of differentially methylated genes were found in the 150ppm and 750 ppm LPN groups, with minimal differentially methylated genes detected in the other groups. Overall, far fewer differentially methylated genes were detected in males than in females (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of genes with altered methylation states following different Pb exposures

| FEMALE | MALE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 ppm | 375 ppm | 750 ppm | 150 ppm | 375 ppm | 750 ppm | |

| PERI | 8 | 255 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 50 |

| EPN | 0 | 52 | 0 | 26 | 1 | 0 |

| LPN | 1770 | 2 | 0 | 148 | 6 | 315 |

Table shows numbers of genes with altered methylation states compared to age matched unexposed animals (p<0.01 and |FC|>1.5 at 0.25 FDR). PERI = perinatal Pb exposure; EPN = early postnatal Pb exposure; LPN = long-term postnatal Pb exposure.

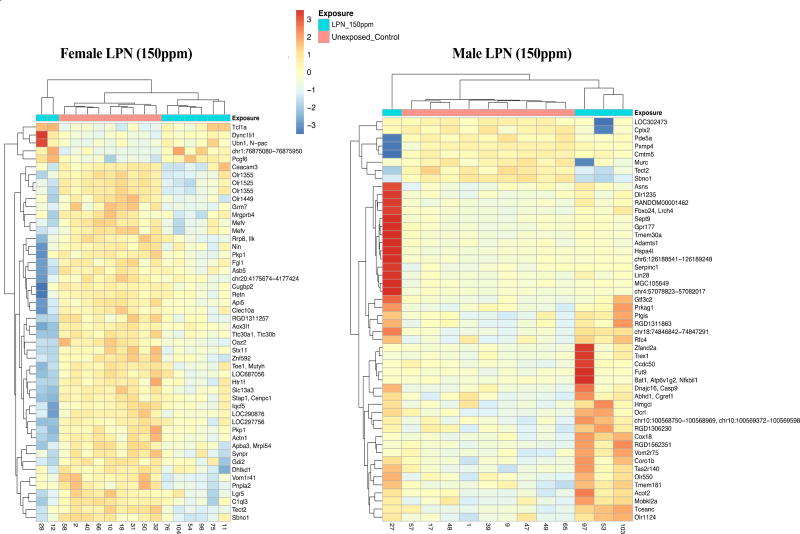

We observed a high number of differentially methylated genes in the LPN 150ppm exposure group both in males and females. Heatmaps of methylation log2 ratios for the top 50 most significant (by p-value) probes in 150 ppm LPN females and males are shown in Figure 3. The effect of Pb exposure on methylation profiles was in opposite directions in male and females at this exposure level, with the majority of differentially methylated genes hypomethylated (91%) in females and hypermethylated in males (83%), as compared to controls. The identified differentially methylated genes were distributed across all the chromosomes and were not clustered on any single chromosome (Fig.S1 and 2)

Figure 3. Representative probe heat maps for LPN 150 ppm males and females.

The heat maps show the methylation log2 ratios for the 50 top-most significant (by p-value) probes in females (left) and males (right) in the long-term postnatal (LPN), 150 ppm exposure groups (compared to untreated controls). Levels 0 to −3 indicate hypomethylation and levels 0 to 3 indicate hypermethylation. The effects in males and females are for the most part in opposite directions.

Examples of functionally relevant genes related to nervous system development and functioning that were hypermethylated in PERI males with 750 ppm exposure were Slc18a1 (synapse related) and Pcdha1 (calcium ion binding) and Ppp1cb (suppressor of learning memory) was hypomethylated. Transcription factors Alx3 and Bbx were hypomethylated in this exposure group. Several genes related to immune system functioning were also identified- Ceacam3 and Eea1 (hypomethylated), Rbpj and Usp31 (hypermethylated). Igf1, an important gene for growth and development was also hypermethylated. Among the 315 genes identified in 750 ppm LPN males, 92% of them were hypermethylated. Among these were genes involved in epigenetic processes (Mettl17a, Smyd5 and Smarcad1), CNS development (Syt2, Prkg1, Pcdhb20, Slc2a3, Klhl1 and Snap29) and transcription (Smad5, Cebpa and Cebpe). In LPN males at the 150ppm exposure level, genes involved in signal transduction Tect2 and Pde5a were hypomethylated. B3galt6, an important gene in glycosaminoglycan synthesis and transcription factor Yy1 were also hypomethylated. Genes involved in transcription regulation (Tceanc, Lin28 and Tef), cell cycle (Cdk1 and Akap8), calcium ion binding (Cgref1) and nuclear encoded mitochondrial gene (Rdh13) were hypermethylated.

In PERI females with 375ppm exposure, genes involved in innate immunity (Kif3b and Ceacam3) and signal transduction (Tect2 and Rap2a) were hypomethylated. Key hypermethylated genes related to the CNS in this exposure group were Folh1, Ppp1ca, Lif, Galnt9, Slc6a5, Gadd45g, ApoE and Fmr1. Histone methyltransferase (Setd7) and wnt signaling regulatory genes (Klh12 and Slc30a90) were hypermethylated as well. Genes associated with schizophrenia (Ntng1), transcription regulation (Tcfap2d and Phf10), and immune response (Cd3e) were hypermethylated in 375 ppm EPN females. The highest number of significant genes that were differentially methylated were identified in 150 ppm LPN females. Hypermethylated genes included those associated with epigenetic processes (Tet1, Suv39h1 and Dnmt3l), neuronal functioning (Egr2, Adam2 and Trhde), tumor suppression (Klf6 and Bmp10), signal transduction (Tect2, Grk1 and Smad3) and immunity and inflammation (Pkp1, Ceacam 1 and 3). Fkbp5, which mediates calcineurin inhibition and stress responses was also hypermethylated. Alzheimer’s disease associated genes (Tktl1 and Gsk3a) were hypomethylated. Exposure to 150 ppm and 375 ppm Pb resulted in opposite effects on DNA methylation levels, as shown in the RDA plot in Figure 2. More hypermethylated and fewer hypomethylated genes were found at the 150ppm exposure level, with fewer hypermethylated genes and more hypomethylated genes observed at the 375ppm exposure level, associated with some exposure periods. In other exposure periods, the opposite was observed, for example, more hypomethylated genes in the 150ppm exposure groups and more hypermethylation in the 375ppm groups. In some instances, the same gene showed opposite changes in methylation status at different exposure levels, while in other instances, the direction of the methylation change was consistent across exposure groups (Table 3). Differential methylation analysis also identified several genes with similar changes in methylation status across developmental exposure periods (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3.

Genes with similar and opposite methylation levels within each sex and developmental exposure stage across different Pb exposure levels

| FEMALE | MALE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERI | EPN | LPN | PERI | EPN | LPN | |||||||

| Hyper | Hypo | Hyper | Hypo | Hyper | Hypo | Hyper | Hypo | Hyper | Hypo | Hyper | Hypo | |

| 150 ppm | Myo10 | x | Rin3 Gmip | x | Golph3 Ppdp Mfrp Dync1li1 Tesp2 | Fabp4, Pmepa1 Tect2 Hrh4 | Olr136 Tmem175 Chac2 | Xrcc4 Stmn2 Dnajc10 | Pragmin Akap14 | Rrp7a Defa8p | Abhd1 Cgref1 | Crabp1 |

| 375 ppm | Myo10 | x | Gmip | Rin3 | Golph3 Fabp4 Ppdp Pmepa1 Mfrp Dync1li1 Tesp2 | Tect2 Hrh4 | Olr136 Tmem175 Chac2 | Xrcc4 Stmn2 Dnajc10 | Defa8p Akap14 | Pragmin Rrp7a | x | Abhd1 Cgref1 Crabp1 |

| 750 ppm | x | x | x | x | Golph3 Mfrp | Hrh4 | Tmem175 | x | Akap14 | x | x | x |

X denotes no result found in the indicated group.

3.3 Gene Ontology (GO) analysis

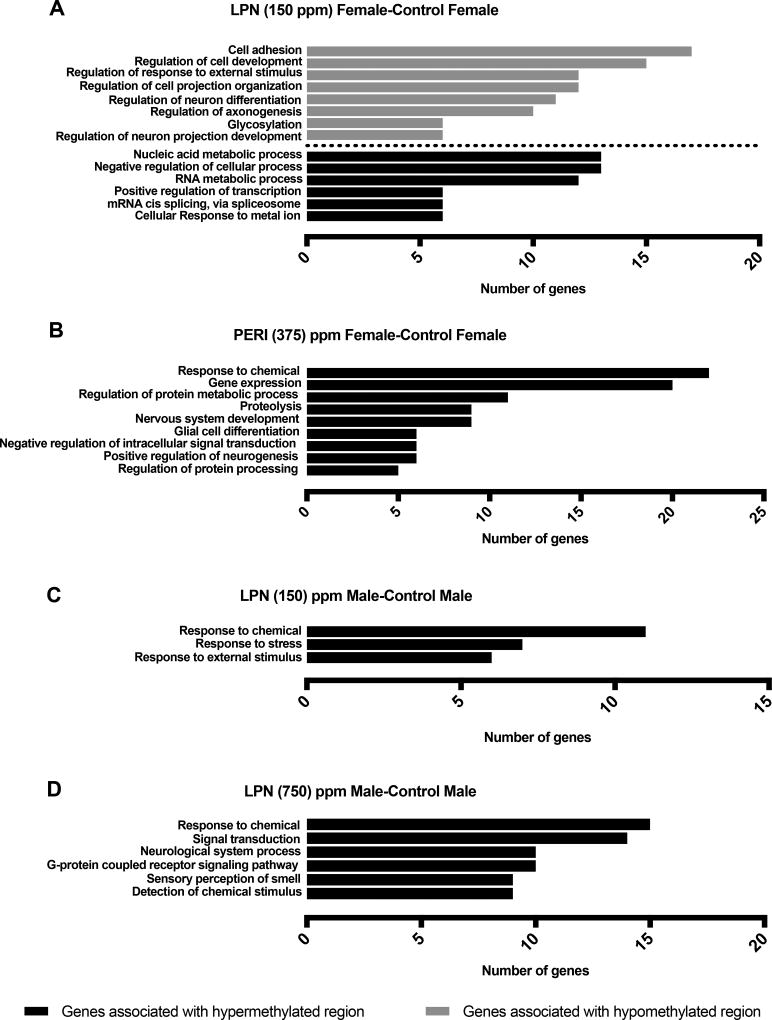

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed on all significantly differentially methylated genes to define the biological processes modulated under different Pb exposure conditions. Biological functions associated with significantly hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes are shown in Figure 4. Based on GO analysis of differentially methylated regions, significantly hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes were found to be associated with biological functions in LPN 150ppm females and males, PERI 375 females, and LPN 750 ppm males, compared to controls (Fig. 4A–D). In other exposure groups significantly over-represented biological functions meeting the selection criteria of p<0.05 with a minimum of 5 genes were not found. Within an exposure group, the functional pathways affected in males and females were different. In Pb exposed females an enrichment for neural development processes was seen along with RNA- and protein- related processes (Fig. 4A and B). In Pb exposed males, biological pathways associated with hypermethylated genes included signaling pathways, stress, and neural responses to stimuli (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis.

The most significantly enriched biological processes categories within hypermethylated genes (black bars) and hypomethylated genes (grey bars) are shown for comparison groups: LPN Female vs Control Female, 150 ppm Pb (A); PERI Female vs Control Female, 375 ppm Pb (B); LPN Male vs Control Male, 150 ppm (C); LPN Male vs Control Male, 750 ppm (D). In these groups significantly overrepresented biological functions composed of minimum of 5 genes at p<0.05 were found.

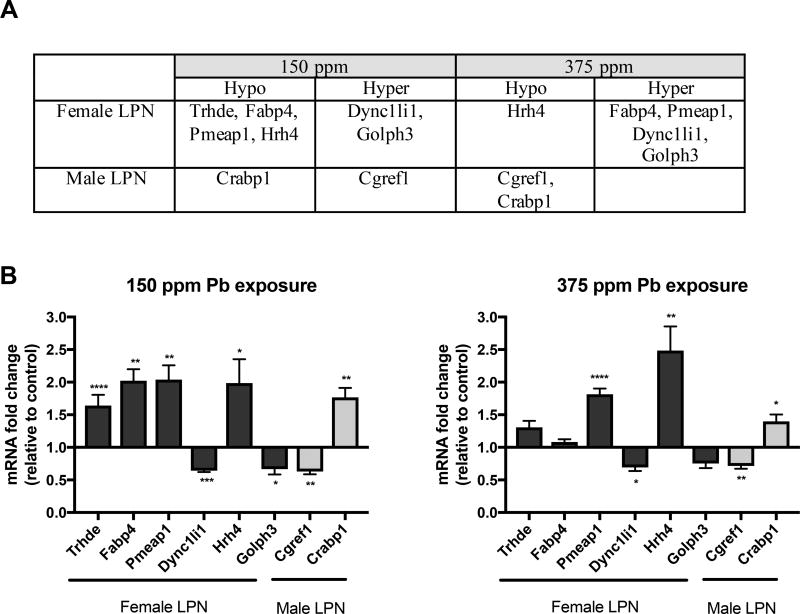

3.4 Relationship of DNA methylation to gene expression

The expression of a select group of genes with significantly altered methylation state were analyzed by qPCR (Fig. 5). In general, at the 150ppm level of exposure a decrease in gene expression was observed with increased methylation levels and an increase in gene expression was associated with hypomethylation. However, at the 375ppm exposure level, expression changes in several of the genes studied did not relate with the methylation status (Fig. 5). Hrh4 gene, hypomethylated in LPN females both at 150ppm and 375 ppm level of exposure, showed consistent significant increase in mRNA expression level as well. Similarly, Dync1li1, hypermethylated at both exposure levels in LPN females, also showed consistent significant decrease in expression at mRNA level.

Figure 5. Relative expression of genes exhibiting hypermethylation and hypomethylation at Pb exposure levels 150 ppm and 375 ppm in LPN Females and Males.

(A) The list of genes selected based on significant methylation change for expression level analysis. (B) The mRNA expression levels were normalized to Gapdh and were expressed as relative to controls (no Pb). Values represent mean ± SEM from N of 6–8; asterisks denote statistically significant change compared to control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

Dynamic changes in DNA methylation occur during brain development and play important roles in influencing the early development and maturation of brain structural and functional organization (Guo et al., 2011; Lister et al, 2013; Tognini et al., 2015). Lead is a developmental neurotoxicant and the present study assessed the potential changes in DNA methylation in the hippocampus associated with developmental Pb exposure and how these changes might be differentially influenced by sex, level of Pb exposure, and the time during development when the exposure occurred. Since promoters are among the genomic regions where the most pronounced functional effects of DNA methylation have been observed in regard to influencing the regulation of gene expression, we used promoter region-focused DNA methylation arrays for this project and identified genes with altered methylation state differentially associated with sex, Pb exposure level and developmental timing of exposure. Previous studies in humans and in animal models have reported significant associations between Pb exposure and changes in global DNA methylation in blood (Pilsner et al, 2009; Wright et al, 2010) but few studies have focused on describing gene-specific DNA methylation changes in the brain (Sanchez-Martin et al, 2015). Additionally, we observed a preponderance of DNA methylation changes in genes associated with neuronal development, synaptic plasticity, metal ion and chromatin modification/organization-related processes, suggesting potentially important functional consequences of Pb exposure on these biologically relevant pathways. Thus, the present results show that developmental Pb exposure can exert a significant influence on the hippocampal methylome.

A main finding from the current study was the sex-specific effect of Pb on DNA methylation. These data are consistent with results from a previous study in which Pb-associated methylated CpG sites were detected in higher numbers in dried peripheral blood spot samples in female children than in male children (Sen et al., 2015). Whether these DNA methylation changes are adaptive or maladaptive in nature remains to be determined. DNA methylation profiles in the brain are sexually dimorphic (Chatterjee et al., 2016; Kurian et al., 2010; McCarthy et al., 2009; Numata et al., 2012) and DNA methylation profiles can be modified by hormonal influences (Schwarz et al., 2010). Potential mechanisms contributing to sex-related differences in DNA methylation could involve sex-related differences in expression of DNA methylation writers (ex., DNA methyltransferases, Dnmt3a) and readers (ex., methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2)). The expression of the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a has been shown to be sexually dimorphic in a brain-region specific manner (Kolodkin and Auger, 2011). Sex differences in MeCP2 expression have also been described in rat amygdala and ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) during steroid sensitive periods of brain development (Kurian et al., 2008; Kurian et al., 2007). Previous work from our lab (Schneider et al., 2013) reported sex, dose (150, 375 and 750 ppm) and developmental period of exposure (PERI and EPN) -dependent changes in Dnmt3a, Dnmt1 and MeCP2 expression in hippocampus following developmental Pb exposure. Dnmt3a expression was increased in PERI males in 150 ppm and 750 ppm dose groups and in the current study, we found the majority of genes hypermethylated at these exposure levels in PERI males. Thus, Pb-induced expression changes in DNA methylation regulators could be an important mechanism underlying sex-related differences in gene specific methylation levels and subsequent gene expression regulation in males and females in response to Pb exposure. Exposure to various heavy metals other than Pb have also been reported to result in altered DNA methylation profiles in brain and other tissues (Martinez-Zamudio and Ha, 2011; Ryu et al., 2015; Tyler and Allan, 2014). For example, exposure to cadmium and arsenic also alter the expression of DNA methyltransferases and their activity (Martinez-Zamudio and Ha, 2011; Ryu et al., 2015) suggesting a general mechanism through which heavy metals may perturb the epigenome.

An interesting finding in this study was identification of changes in methylation of genes involved in neurobehavioral functions. For example, Ppp1cb, associated with suppression of learning and memory, was hypomethylated in PERI males. We have previously shown that Pb-exposed PERI male rats have memory deficits in a trace fear conditioning task but Pb-exposed PERI females are unaffected (Anderson et al., 2016). Hypomethylation of Ppp1cb in PERI males could be a mechanism at least in part contributing to the memory impairment in these animals. Lead is known to exert its neurotoxic effects by competing with calcium for calcium receptors (Flora et al., 2012) and in this study we found several genes involved in calcium binding (Pcdha1, Pcdhb20 and Cgref1) to be hypermethylated in PERI and LPN males. Ntng1, implicated in pathogenesis of schizophrenia (Wu et al., 2016) was hypermethylated in EPN females and Tktl1, a proto-oncogene, associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Coy et al., 2005) was hypomethylated in LPN females. ApoE genetic polymorphism has been associated with toxicokinetics of Pb (Stewart et al., 2002) and Alzheimer’s disease risk (Liu et al., 2013) was hypermethylated in PERI females.

Probe segregation by Pb exposure level and developmental period of exposure was not as clear as the influence of sex on the DNA methylation pattern. Interestingly, the effect of Pb exposure at 150 ppm and 375 ppm levels on DNA methylation was in opposite directions. The mechanisms underlying these types of effects of Pb exposure on DNA methylation levels are not clear but it is possible that at different levels of Pb exposure, additional epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modifications, are engaged and through their cross-talk with DNA methylation, affect methylation levels (Du et al., 2015; Hashimoto et al., 2010). Future studies of the activation/deactivation of molecular events consequent to different Pb exposures could be important for understanding the functional outcomes of Pb exposure and differentiating between toxic and compensatory responses.

Animals with low level (150ppm) LPN exposure had the greatest number of genes with altered methylation patterns in both males (148) and females (1770), suggesting that exposure to Pb over a longer period of time could lead to more pronounced epigenetic changes and may be relevant to humans in whom exposures to Pb are often not limited to a brief exposure time (CDC, 2012; Telisman et al., 2000). The rat hippocampus is still developing after birth and attains functional maturity during postnatal life (Jones et al., 2003). The longer a potent neurotoxicant like Pb is present in the system the more detrimental the effect is likely to be on the epigenome and gene expression. In further support of this premise, the groups with the lowest number of differentially methylated genes were the animals, males and females, with EPN Pb exposures: EPN exposures occurred for the shortest period of time of all the treatment groups (i.e., from birth to weaning). Although only a small number of differentially methylated genes were detected in the EPN groups, it is possible that more DNA methylation changes could be occurring but at genomic regions (enhancers and gene body) other than at promoters. It has been reported commonly in environmental epigenetics studies that the effects of exposure on DNA methylation are of smaller magnitude and are widespread (Breton et al., 2017) and identifying altered methylated regions using genomic regions specific platform might not provide overall effect of environmental exposure. Hence mapping DNA methylation using assays that provide greater resolution and more coverage of the genome than the currently used promoter arrays may reveal novel aspects of genome-wide, site-specific methylome changes.

The relationship between Pb exposure level and functional outcomes is often non-linear in nature (Lanphear et al., 2005; Lasley and Gilbert, 2002; White et al., 2007). Our results on methylation patterns across the three exposure concentrations used, also show that a non-linear dose-response relationship exists at the genomic DNA methylation level as well. The mechanisms underlying this non-linear Pb dose-response effect on DNA methylation are not clear but may involve differential regulation of DNA methylation pathways with different Pb exposures as well as potential differences in functional coupling/decoupling with other epigenetic mechanisms such as histone modifications.

One limitation of this study is our use of a promoter-based array. Gene body methylation and methylation changes even at a single CpG site have potentially strong effects on gene expression and our approach of using a only promoter-based array limited us from finding such methylation-related changes (Jones, 2012; Penner et al., 2016; Rojas, et al., 2015; Xin et al., 2011). It is possible that an association between methylation levels and gene expression was not observed in the 375ppm exposure group because genomic regions other than the promoter region may have preferentially undergone methylation changes that could not be detected with the promoter array. Additionally, the identified regions may not be solely responsible for controlling the gene expression levels. The possibility exists that mechanistic events triggered by different Pb exposures, such as context-specific DNA methylation, might be quite different. Also, gene regulation is a complex process and involves epigenetic mechanisms other than DNA methylation that were not examined in the current study but may play important roles in mediating the outcomes from Pb exposure. This may also be a reason why DNA methylation levels and gene expression changes do not always correlate (Bock et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2017). We observed an association between mRNA expression and DNA methylation in the 150ppm exposure group but not in the 375ppm exposure group except for genes Hrh4 and Dync1li1 in females. Hrh4 and Dync1li1 genes were consistently hypomethylated and hypermethylated, respectively, at both exposure levels in LPN groups. Gene expression patterns corresponding to methylation status were observed at both exposure levels. Previously, a negative correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression was observed in female but not in male mice with perinatal Pb exposure (Sanchez-Martin et al., 2015) and with exposures to other toxic metals such as arsenic (Boellmann et al., 2010; Rojas et al., 2015). DNA methylation changes at promoters following heavy metal exposure may not always be the determining factor for controlling gene expression. Changes at other genomic regions and other epigenetic mechanisms might have further functional consequences at the gene expression level. Additionally, as the methylation status of some genes (ex., Golph3, Mfrp, Hrh4 and Dync1li1 in females; Tmem175 and Akap14 in males) seemed to be affected across all exposure levels, it raises the possibility that these could potentially be sets of sex-specific Pb-responsive genes. This possibility needs to be assessed with additional studies examining the methylation status and expression levels of these genes in other brain regions and in blood.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that developmental Pb exposures result in methylation changes at gene promoter regions and effects vary depending on sex, amount of Pb exposure and developmental window and duration of Pb exposure. These results provide further evidence for the alteration of potentially important epigenetic processes that may play important roles in regulating brain development and function, as a result of exposure to Pb. Since epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation, are reversible in nature, future studies aimed at studying ways to reverse Pb-induced epigenetic alterations and their associated changes in gene expression and functional outcomes may be a fruitful approach towards remediating Pb-induced brain damage.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Pb exposure in rats altered the hippocampal methylome at the gene promoter level.

These changes are differentially associated with sex, Pb exposure level and timing.

Sex is most significantly associated with observed methylation changes.

Neural development and function genes were differentially methylated by Pb.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 ES015295.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- ACCLPP. Low level lead exposure harms children: A renewed call for primary prevention 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Adriaens ME, Jaillard M, Eijssen LM, Mayer CD, Evelo CT. An evaluation of two-channel ChIP-on-chip and DNA methylation microarray normalization strategies. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DW, Mettil W, Schneider JS. Effects of low level lead exposure on associative learning and memory in the rat: Influences of sex and developmental timing of exposure. Toxicol Lett. 2016;246:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock C, Beerman I, Lien WH, Smith ZD, Gu H, Boyle P, Gnirke A, Fuchs E, Rossi DJ, Meissner A. DNA methylation dynamics during in vivo differentiation of blood and skin stem cells. Mol Cell. 2012;47(4):633–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boellmann F, Zhang L, Clewell HJ, Schroth GP, Kenyon EM, Andersen ME, Thomas RS. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression changes in the mouse lung following subchronic arsenate exposure. Toxicol Sci. 2010;117(2):404–17. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton CV, Marsit CJ, Faustman E, Nadeau K, Goodrich JM, Dolinoy DC, Herbstman J, Holland N, LaSalle JM, Schmidt R, et al. Small-Magnitude Effect Sizes in Epigenetic End Points are Important in Children’s Environmental Health Studies: The Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center’s Epigenetics Working Group. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(4):511–526. doi: 10.1289/EHP595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield RL, Henderson CR, Jr, Cory-Slechta DA, Cox C, Jusko TA, Lanphear BP. Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 microg per deciliter. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1517–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (CDC) CfDC. Preventing lead poisioning in young children 1991 [Google Scholar]

- CDC. CDC Response to Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Recommendations in “Low Level Lead Exposure Harms Children: A Renewed Call of Primary Prevention” 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Lagisz M, Rodger EJ, Zhen L, Stockwell PA, Duncan EJ, Horsfield JA, Jeyakani J, Mathavan S, Ozaki Y, et al. Sex differences in DNA methylation and expression in zebrafish brain: a test of an extended ‘male sex drive’ hypothesis. Gene. 2016;590(2):307–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell EC, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult disease. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2009;3:19. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.019.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coy JF, Dressler D, Wilde J, Schubert P. Mutations in the transketolase-like gene TKTL1: clinical implications for neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes and cancer. Clin Lab. 2005;51(5–6):257–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Johnson LM, Jacobsen SE, Patel DJ. DNA methylation pathways and their crosstalk with histone methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(9):519–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulk C, Barks A, Liu K, Goodrich JM, Dolinoy DC. Early-life lead exposure results in dose- and sex-specific effects on weight and epigenetic gene regulation in weanling mice. Epigenomics. 2013;5(5):487–500. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora G, Gupta D, Tiwari A. Toxicity of lead: A review with recent updates. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2012;5(2):47–58. doi: 10.2478/v10102-012-0009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeleher P, Hartnett L, Egan LJ, Golden A, Raja Ali RA, Seoighe C. Geneset analysis is severely biased when applied to genome-wide methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(15):1851–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Ma DK, Mo H, Ball MP, Jang MH, Bonaguidi MA, Balazer JA, Eaves HL, Xie B, Ford E, et al. Neuronal activity modifies the DNA methylation landscape in the adult brain. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(10):1345–51. doi: 10.1038/nn.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Vertino PM, Cheng X. Molecular coupling of DNA methylation and histone methylation. Epigenomics. 2010;2(5):657–69. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernberg S. Lead Poisoning in a Historical Perspective. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2000;38:244–254. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200009)38:3<244::aid-ajim3>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(4):253–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(7):484–92. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SP, Rahimi O, O’Boyle MP, Diaz DL, Claiborne BJ. Maturation of granule cell dendrites after mossy fiber arrival in hippocampal field CA3. Hippocampus. 2003;13(3):413–27. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin MH, Auger AP. Sex difference in the expression of DNA methyltransferase 3a in the rat amygdala during development. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23(7):577–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Bychowski ME, Forbes-Lorman RM, Auger CJ, Auger AP. Mecp2 organizes juvenile social behavior in a sex-specific manner. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;9(28) doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1345-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Forbes-Lorman RM, Auger AP. Sex difference in mecp2 expression during a critical period of rat brain development. Epigenetics. 2007;2(3):173–8. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.3.4841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Olesen KM, Auger AP. Sex differences in epigenetic regulation of the estrogen receptor-alpha promoter within the developing preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2010;151(5):2297–305. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, Yolton K, Baghurst P, Bellinger DC, Canfield RL, Dietrich KN, Bornschein R, Greene T, et al. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(7):894–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasley SM, Gilbert ME. Rat hippocampal glutamate and GABA release exhibit biphasic effects as a function of chronic lead exposure level. Toxicol Sci. 2002;66(1):139–47. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/66.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidsky TI, Schneider JS. Lead neurotoxicity in children: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 1):5–19. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YC, Li J, Ni Y, Liang Q, Zhang J, Yeo GSH, Lyu J, Jin S, Ding C. A complex association between DNA methylation and gene expression in human placenta at first and third trimesters. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0181155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR, Urich M, Puddifoot CA, Johnson ND, Lucero J, Huang Y, Dwork AJ, Schultz MD, et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science. 2013;341(6146):1237905. doi: 10.1126/science.1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2013;9(2):106–18. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JT, Chen BY, Zhang JQ, Kuang F, Chen LW. Lead exposure induced microgliosis and astrogliosis in hippocampus of young mice potentially by triggering TLR4-MyD88-NFkappaB signaling cascades. Toxicol Lett. 2015;239(2):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llop S, Lopez-Espinosa MJ, Rebagliato M, Ballester F. Gender differences in the neurotoxicity of metals in children. Toxicology. 2013;311(1–2):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Zamudio R, Ha HC. Environmental epigenetics in metal exposure. Epigenetics. 2011;6(7):820–7. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Auger AP, Bale TL, De Vries GJ, Dunn GA, Forger NG, Murray EK, Nugent BM, Schwarz JM, Wilson ME. The epigenetics of sex differences in the brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29(41):12815–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3331-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman HL, Schell A, Bellinger D, Leviton A, Allred EN. The long-term effects of exposure to low doses of lead in childhood. An 11-year follow-up report. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(2):83–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numata S, Ye T, Hyde TM, Guitart-Navarro X, Tao R, Wininger M, Colantuoni C, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE, Lipska BK. DNA methylation signatures in development and aging of the human prefrontal cortex. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(2):260–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner MR, Parrish RR, Hoang LT, Roth TL, Lubin FD, Barnes CA. Age-related changes in Egr1 transcription and DNA methylation within the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2016;26(8):1008–20. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilsner JR, Hu H, Ettinger A, Sanchez BN, Wright RO, Cantonwine D, Lazarus A, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Mercado-Garcia A, Tellez-Rojo MM, et al. Influence of prenatal lead exposure on genomic methylation of cord blood DNA. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(9):1466–71. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Broadbent J, Harrington H, Sugden K, Houts RM, Ramrakha S, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Association of Childhood Blood Lead Levels With Cognitive Function and Socioeconomic Status at Age 38 Years and With IQ Change and Socioeconomic Mobility Between Childhood and Adulthood. JAMA. 2017;317(12):1244–1251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas D, Rager JE, Smeester L, Bailey KA, Drobna Z, Rubio-Andrade M, Styblo M, Garcia-Vargas G, Fry RC. Prenatal arsenic exposure and the epigenome: identifying sites of 5-methylcytosine alterations that predict functional changes in gene expression in newborn cord blood and subsequent birth outcomes. Toxicol Sci. 2015;143(1):97–106. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu HW, Lee DH, Won HR, Kim KH, Seong YJ, Kwon SH. Influence of toxicologically relevant metals on human epigenetic regulation. Toxicol Res. 2015;31(1):1–9. doi: 10.5487/TR.2015.31.1.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Martin FJ, Lindquist DM, Landero-Figueroa J, Zhang X, Chen J, Cecil KM, Medvedovic M, Puga A. Sex- and tissue-specific methylome changes in brains of mice perinatally exposed to lead. NeuroToxicol. 2015;46:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JS, Anderson DW, Kidd SK, Sobolewski M, Cory-Slechta DA. Sex-dependent effects of lead and prenatal stress on post-translational histone modifications in frontal cortex and hippocampus in the early postnatal brain. NeuroToxicol. 2016;54:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JS, Kidd SK, Anderson DW. Influence of developmental lead exposure on expression of DNA methyltransferases and methyl cytosine-binding proteins in hippocampus. Toxicol Lett. 2013;217(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Nugent BM, McCarthy MM. Developmental and hormone-induced epigenetic changes to estrogen and progesterone receptor genes in brain are dynamic across the life span. Endocrinology. 2010;151(10):4871–81. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, Heredia N, Senut MC, Hess M, Land S, Qu W, Hollacher K, Dereski MO, Ruden DM. Early life lead exposure causes gender-specific changes in the DNA methylation profile of DNA extracted from dried blood spots. Epigenomics. 2015;7(3):379–93. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivey A. The weight of lead. Effects add up in adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):A30–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.115-a30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart WF, Schwartz BS, Simon D, Kelsey K, Todd AC. ApoE genotype, past adult lead exposure, and neurobehavioral function. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(5):501–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telisman S, Cvitkovic P, Jurasovic J, Pizent A, Gavella M, Rocic B. Semen quality and reproductive endocrine function in relation to biomarkers of lead, cadmium, zinc, and copper in men. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(1):45–53. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0010845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognini P, Napoli D, Pizzorusso T. Dynamic DNA methylation in the brain: a new epigenetic mark for experience-dependent plasticity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:331. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler CR, Allan AM. The Effects of Arsenic Exposure on Neurological and Cognitive Dysfunction in Human and Rodent Studies: A Review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2014;1:132–147. doi: 10.1007/s40572-014-0012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma G, Sobolewski M, Cory-Slechta DA, Schneider JS. Sex- and brain region-specific effects of prenatal stress and lead exposure on permissive and repressive post-translational histone modifications from embryonic deveolpment through adulthood. NeuroToxicol. 2017;62:207–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vryer R, Saffery R. What’s in a name? Context-dependent significance of ‘global’ methylation measures in human health and disease. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:2. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Guan RL, Liu MC, Shen XF, Chen JY, Zhao MG, Luo WJ. Lead Exposure Impairs Hippocampus Related Learning and Memory by Altering Synaptic Plasticity and Morphology During Juvenile Period. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(6):3740–3752. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LD, Cory-Slechta DA, Gilbert ME, Tiffany-Castiglioni E, Zawia NH, Virgolini M, Rossi-George A, Lasley SM, Qian YC, Basha MR. New and evolving concepts in the neurotoxicology of lead. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;225(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RO, Schwartz J, Wright RJ, Bollati V, Tarantini L, Park SK, Hu H, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Baccarelli A. Biomarkers of lead exposure and DNA methylation within retrotransposons. Environ Health Perspect. 2010a;118(6):790–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Yao YG, Luo XJ. SZDB: A Database for Schizophrenia Genetic Research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2016;43(2):11. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y, O’Donnell AH, Ge Y, Chanrion B, Milekic M, Rosoklija G, Stankov A, Arango V, Dwork AJ, Gingrich JA, et al. Role of CpG context and content in evolutionary signatures of brain DNA methylation. Epigenetics. 2011;6(11):1308–18. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.11.17876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.