Abstract

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are responsible for reversing mono- and poly-ubiquitination of proteins and play essential roles in numerous cellular processes. Close to 100 human DUBs have been identified and are classified into five families, with the ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) family being the largest one (> 50 members). The binding of ubiquitin (Ub) to USP is strikingly different from that observed for the DUBs in the ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCH) and ovarian tumor domain protease (OTU) families. We generated a panel of mutant ubiquitins and used them to probe the ubiquitin’s interaction with a number of USPs. Our results revealed a remarkable divergence of USP-Ub interactions among the USP catalytic domains. Our double mutant cycle analysis targeting the ubiquitin residues located in the tip, the central body, and the tail of ubiquitin also demonstrated different crosstalk among the USP-Ub interactions. This work uncovered intriguing divergences in the ubiquitin-binding mode in the USP family DUBs and raised the possibility of targeting the ubiquitin-binding hotspots on USPs for selective inhibition of USPs by small molecule antagonists.

Keywords: deubiquitinase, ubiquitin binding, double mutant cycle analysis, synergistic interaction

Introduction

Ubiquitination is an essential posttranslational modification that regulates a wide range of cellular processes including protein degradation, cell cycle, transcription, and DNA damage response1,2. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are essential for many of the cellular processes by reversing protein mono- and poly-ubiquitination. Deregulation of DUBs have been linked to a number of human diseases including autoimmune disorders3–5, Machado-Josephine disease6–8, Parkinson’s disease9–11, prostate cancer12, and colon cancer13,14. Therefore DUBs as viable therapeutic targets have attracted great interest in recent years.

To date, several crystal structures of ubiquitin specific proteases (USPs) in the apo-form or in complex with ubiquitin (Ub) have been reported, including CYLD, USP2, USP4, USP5, USP7, USP8, USP14, USP21, and USP4615–25. A close inspection of Ub binding mode of USPs in comparison to that of the ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCH), ovarian tumor domain (OTU), Machado-Joseph domain (MJD) and Jab1/Mov34/Mpr1 (JAMM) family DUBs revealed clear distinctions. The DUBs in the UCH, OTU, MJD, and JAMM families primarily bind ubiquitin (Ub) at the S1 site through its C-terminal tail with limited contact with the body of Ub6,26–32. In contrast, USPs bind Ub mainly in three regions: 1) the Ub C-terminal tail that binds in a cleft formed by the USP thumb and palm subdomains; 2) the N-terminal region of Ub (spatially close to the N-terminus of Ub) that interacts closely with the USP finger subdomain; 3) the palm subdomain that interacts with the central region of Ub (see Figure 1A). Although this Ub binding mode is likely essential for USP catalysis and specificity based on the available structural information15,17,22, an in-depth biochemical investigation has not been reported.

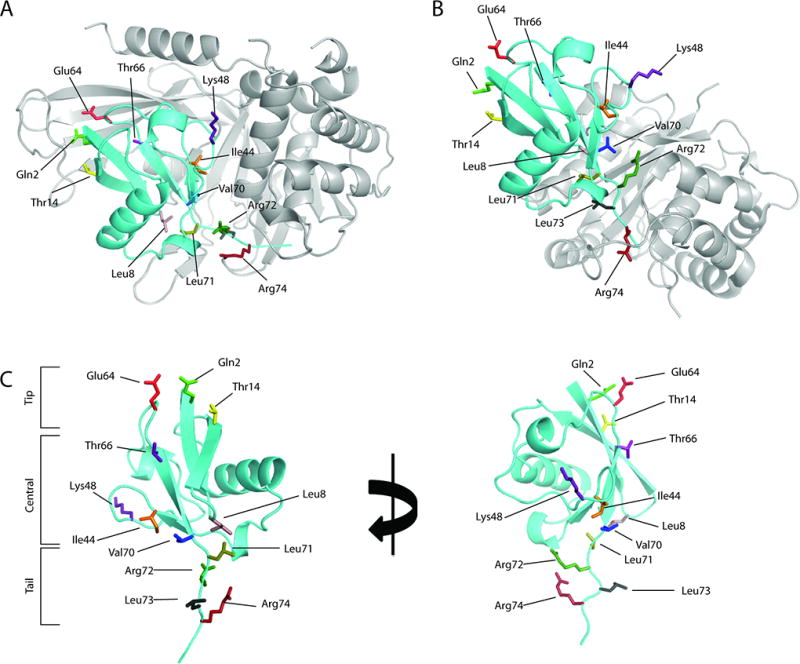

Figure 1.

Structures of ubiquitin (Ub) and DUB-Ub complexes. Structures of USP2 (A) and UCH-L1 (B) in complex with ubiquitin (PDB 2IBI and 3KW5 respectively). (C) The Ub residues that are mutated to alanine to probe Ub-USP interaction. We divide the Ub residues into three regions based on the Ub three-dimensional structure. Ub residues Gln2, Thr14 and Glu64 are identified as the “tip” region and are located close to the N-terminal region of Ub. We refer to the Ub C-terminal region as the Ub “tail” which includes residues Leu71, Arg72, Leu73 and Arg74. Residues Leu8, Ile44, Lys48, Thr66, and Val 70 which are located between the “tip” and “tail” regions are identified in the central region.

Additionally, hydrophobic interactions between Ub and Ub-binding domains and motifs are important for the recognition of Ub by ubiquitin binding proteins and the interactions are often mediated through the Ile44 patch on Ub33,34. The same Ile44 hydrophobic patch was suggested to contribute to Ub’s binding to DUBs in the UCH (Figure 1B) and MJD families31,35. However, little is known about the role of the surface hydrophobic residues on Ub in its binding to USPs. Another interesting observation of the USP-family DUBs is a zinc ribbon located at the “tip” of the finger subdomain of many but not all USPs. Notably several USPs have apparently lost the zinc-binding residues at the fingertip as exemplified by USP736. Although the precise role of the zinc ribbon in USP remains unclear, removal of the zinc ion binding in USP15 was found to reduce its activity in polyUb chain cleavage37. A recent crystal structure of USP21 in complex with linear diUb suggested that the zinc-ribbon may participate in the binding of the distal Ub22.

While available structures of USP catalytic domains revealed a conserved core domain structure15,17,20,21, it is not clear whether the binding of Ub to USPs is conserved. A sequence analysis revealed that only approximately 25% of surface residues of the USP catalytic domains are conserved38. Moreover, Ub variants were recently generated with varied binding specificity for several DUBs38,39. Thus it is possible that Ub’s binding to USPs is intrinsically diverse despite an overall structural conservation of the USP catalytic domains. This also raises the intriguing potential of developing small molecule inhibitors that target the non-conserved regions on USPs to achieve specific inhibition of this family of DUBs.

To explore the residue-specific interactions, we generated a series of Ub alanine mutants. We used available cocrystal structures to identify Ub surface residues that interact with USPs through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds or salt bridges. Our kinetics data revealed clear distinctions among USPs in the deubiquitination assay. Furthermore, our double mutant cycle analyses that targeted residues located at the Ub “tip”, the central body and the “tail” (Figure 1C) revealed different modes of interactions (synergistic, additive or antagonistic) among USPs.

Methods

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis

Human USP2 catalytic domain (USP2CD, amino acids 259—605), USP7 catalytic domain (USP7CD, amino acids 208—564) and USP7 catalytic domain with Ub-like domains 4 and 5 (USP7CD45, amino acids 208—564 and 890—1102 with a Leu and Glu linker) was cloned into pET-28a vector based on constructs previously reported except that the GST tag was not included in our construct16,40. USP8 catalytic domain (USP8CD, amino acids 734—1110) in pET-28a was generously donated by Dr. Sirano Dhe-Pagano20. USP21 catalytic domain (USP21CD, amino acids 209—562) in pET-28a was purchased from Addgene (3MTN) in expression vector. C476S/C479S USP2CD, V337C/A381C/H384C USP7CD, C985S/988S USP8CD and C437S/C440S USP21CD were constructed by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis. Yeast Ub (amino acid 1 to 75) was amplified by PCR then cloned into E. coli expression plasmid pTYB1 using NdeI and SapI restriction sites as reported40. The gene was then mutated by QuikChange protocol (residues S19P, D24E, and S28A) to express humanized Ub. Further mutagenesis through QuikChange was used to introduce point mutations Q2A, L8A, T14A, I44A, K48A, E64A, T66A, V70A, L71A, R72A, L73A, and R74A to Ub in pTYB1 vector, which allowed the expression of the humanized Ub 1—75 as an intein fusion.

Expression and purification of deubiquitinating enzymes

Wild-type and C476S/C479S USP2CD were expressed in Rosetta(DE3) cell line (Novagen). Wild-type and V337C/A381C/H384C USP7CD, USP7CD45, wild-type and C985S/C988S USP8CD, wild-type and C437S/C440S USP21CD were expressed in BL21(DE3) cell line. Cells were cultured at 37 °C until OD600 of 0.6. Cultures were then temperature was adjusted to 15 °C and induced with 0.2 mM IPTG then allowed to grown overnight. For purification of wild-type and C476S/C479S USP2CD, wild-type and V337C/A381C/H384C USP7CD, USP7CD45, wild-type and C437S/C440S USP21CD cell pellets were suspended in a lysis buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM imidazole. Wild-type and C985S/988S USP8CD was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, ad 10 mM imidazole. Cell free extract was bound to Ni NTA resin (Invitrogen) and washed with buffer containing 20 mM imidazole. Proteins were eluted in its respective lysis buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Eluted protein was concentrated and loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 (GE Life Sciences) and eluted using the buffers indicated below. For the wild-type and mutant USP2CD, a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT was used. For the wild-type and mutant USP7CD as well as USP7CD45 a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT was used. For USP8CD a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT was used. For USP21CD a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.0), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT was used. For USP21CD, following the HiLoad chromatography the pooled fractions were loaded onto a HiTrap SP column (GE Lifesciences) using a buffer containing 25 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 1 mM DTT. A salt gradient of 50 to 500 mM NaCl was used to elute USP21. Wild-type and mutant USP2CD, USP7CD, USP7CD45 and USP8CD were dialyzed against their respective HiLoad buffer with the addition of 5% glycerol. Purity of the protein was estimated to be 90% or greater by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining.

Preparation of wild-type and mutant Ub-AMC

To generate Ub-AMC, the wild-type or mutant Ub (amino acids 1—75) was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells as an intein fusion protein following a previously reported protocol40. Cells were grown at 37 °C until OD600 of 0.6. The cell culture was induced with 0.2 mM ITPG at 15 °C and grown overnight. The cells were resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM PMSF before sonication. Ub1—75-intein was bound to the chitin affinity beads (New England Biolabs) for 4 hours at 4 °C and washed with the high salt buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol], followed by a wash with the low salt buffer [20 mM MES (pH 6.5), 100 mM NaCl]. Ub1—75 was cleaved off the column by 75 mM sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (MESNA) in the low salt buffer for 9 hours at room temperature before elution. The eluted Ub1—75-MESNA was buffer exchanged with 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 6.5) and concentrated to 4 mg/mL. The concentrated protein solution was then incubated with glycine-AMC (10 mg/mL), N-hydroxysuccinimide (5 mg/mL) and collidine (20 mg/mL) in an aqueous solution containing 20% DMSO. The reaction was allowed for 40 hours at room temperature with rotation. The product was purified by HPLC using a Phenomenex Jupiter C18 column (300 Å, 10 µm, 250 × 10 mm) with an acetonitrile gradient of 10% to 35%. Both the wild-type and mutant Ub-AMC eluted at approximately 27% acetonitrile. The HPLC fractions containing pure Ub-AMC were speedvaced, resuspended in DMSO, and stored at −80 °C. Double mutant T66A/R74A Ub-AMC required a refolding step and the lyophilized protein was resuspended in 100 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, and 8 M urea then dialyzed against 20 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.4) and 100 mM NaCl. Yield varied for the wild-type and mutant Ub-AMC from approximately 50% to 70%.

Steady-State Kinetics Analysis

In vitro deubiquitinating activity was assayed using wild-type and mutated fluorogenic substrate ubiquitin 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Ub-AMC) generated as described above. Enzyme and Ub-AMC were incubated in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, and 1 mM DTT at 25 °C. Fluorescence was measured using a Fluoromax-4 fluorescence spectrometer (Horiba) with an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 440 nm. Initial rates were analyzed by fitting to the Michaelis-Menton equation using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The kcat was determined by dividing Vmax with the enzyme concentration used in the assay. USP2CD (1 to 10 nM), USP7CD45 (1 to 100 nM), USP8CD (1 to 100 nM), USP21CD (10 to 100 nM) and UCH-L1 (10 to 100 nM) were used for the wild-type and mutant Ub-AMC. The standard error of the mean (SEM) of the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) was determined by error propagation.

Double Mutant Cycle Analysis

Double mutant cycle analysis of Ub mutants was carried out as previously described41–43. ΔΔGMut was calculated using equation 1:

| (1) |

where (kcat/Km)Mut refers to single or double Ub mutants. R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin (298 K). Coupling energy (ΔGI) was determined using equation 2:

| (2) |

ΔGI was used to determine the nature of double mutant interaction, including additive, synergistic and antagonistic interactions.

Detection and quantification of zinc ion binding

Determination of zinc content was performed as previously described44. Enzymes were dialyzed into a saturation buffer [30 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, 350 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM DTT and 50 µM zinc sulfate]. A zinc depleted buffer was generated by mixing Chelex 100 resin (BioRad) with HNG buffer [30 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 10% glycerol, and 350 mM sodium chloride]. Chelex 100 was separated from the buffer. Zinc depleted HNG buffer was used to remove ambient zinc ions from enzymes in a two-step dialysis. Enzyme concentration for zinc detection assay were 5 µM for the wild-type and V337C/A381C/H384C USP7CD and 1 µM for the wild-type and C476S/C479S USP2CD. Enzymes were added to zinc depleted HNG buffer containing 0.1 mM 4-(2-pyridylazo)-resorcinol (PAR). Increasing concentrations of p-hydroxymercuribenzoic acid sodium salt (PHMB) was titrated into the mixture to release zinc ions from the proteins. Concentration of Zn2+(PAR)2 complex was calculated using absorbance at 500 nm and extinction coefficient 66,000 M−1cm−1. Zinc depleted HNG buffer was used as a control.

Results

Alanine-scanning mutation analysis of ubiquitin as a substrate of USPs

Cocrystal structures of USP2, USP7, and USP21 with Ub revealed that USPs interact with Ub at the tip, central body, and tail of Ub (Figure 1A and C). To explore the interactions between USP and Ub at the various positions, we selected Gln2, Leu8, Thr14, Ile44, Lys48, Glu64, Thr66, Val70, Leu71, Arg72, Leu73 and Arg74 on Ub for alanine-scanning mutation analysis (Figure 1A and C). Among the residues selected, Gln2, Thr14 and Glu64 are located in the tip of Ub, and interact with the finger subdomain of USP (Figure 1A and C). Thr66, Ile44, Lys48, Val70 and Leu8 are located on the β-sheet that wraps around the α-helix as found in the β-grasp fold of Ub as part of the Ub central body. Ile44, Val70 and Leu8 form the Ub hydrophobic patch that interacts with many Ub binding domains and motifs. Residues Leu8, Lys48, and Val70 are at the interface between Ub and the finger and palm subdomains on USP. Leu71, Arg72, Leu73 and Arg74 are located on the tail of Ub and likely contribute to the binding of the Ub tail peptide (LRLRGG) to the active site cleft formed by the USP palm and thumb subdomains. We generated the panel of mutant Ub-AMC including Q2A, L8A, T14A, I44A, K48A, E64A, T66A, V70A, L71A, R72A, L73A and R74A.

We first obtained kinetic data for the wild-type USP2 catalytic domain (USP2CD) using the complete panel of mutant Ub-AMC. The Ub mutants can be classified into three categories based on the catalytic efficiency of deubiquitination by USP2CD, i.e. little-to-no effect (the kcat/Km is decreased by <5 fold), modest effect (the kcat/Km is decreased by 5 to 50 fold) and severe effect (the kcat/Km is decreased by > 50 fold). We also observed a small increase in kcat/Km for several mutants, which we categorize as little-to-no effect. For USP2CD, a number of the Ub mutations had little-to-no effect on the catalytic efficiency of deubiquitination, including Q2A, T14A, K48A, E64A, V70A, L71A, and L73A (Figure 2A). In fact, L71A and L73A mutations resulted in an increase in kcat/Km (3.9 and 2.8 fold respectively). Four mutations, L8A, T66A, R72A and R74A, led to a modest decrease in catalytic efficiency (5—10 fold decrease in kcat/Km) (Figure 2A). Overall, USP2CD is insensitive to the mutations introduced to the various sites on Ub.

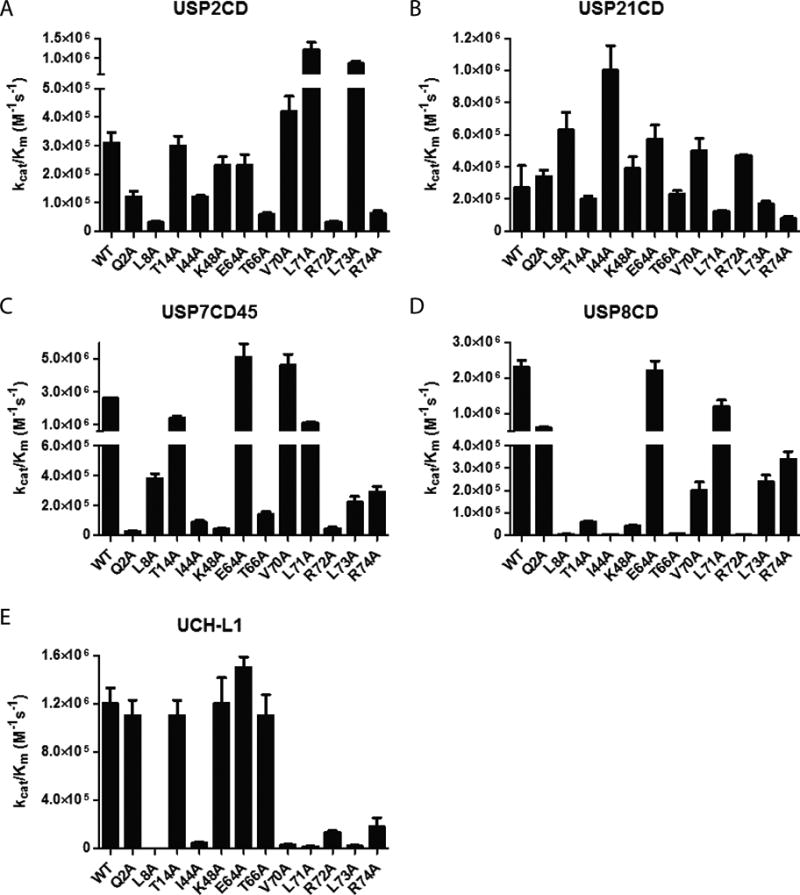

Figure 2.

The catalytic efficiency of USP2CD (A), USP21CD (B), USP7CD45 (C), USP8CD (D) and UCH-L1 (E) determined using the wild-type and mutant Ub-AMC substrates.

Similar to USP2CD, the catalytic domain of USP21 (USP21CD) was assayed using the same panel of mutant Ub substrates (Figure 2B). The only mutant that displayed a modest decrease in catalytic efficiency was R72A Ub. The rest of the Ub mutants, Q2A, L8A, T14A, I44A, K48A, E64A, T66A, V70A, L71A, L73A, and R74A showed little effect on the deubiquitination by USP21CD.

USP7 catalytic domain is intrinsically low in deubiquitination activity16. It was reported that the USP7 catalytic domain fused with the Ub-like domains 4 and 5 in USP7 (USP7CD45) possesses activity comparable to that of the full length USP7 and can be readily expressed and purified from E. coli16. We thus purified USP7CD45 and confirmed that the DUB activity of USP7CD45 was similar to that of the full length USP7 assayed using the wild-type Ub-AMC substrate16. Next we determined the catalytic efficiency of USP7CD45 in deubiquitinating the panel of Ub-AMC mutants. The Ub mutations T14A, E64A, V70A, and L71A had little effect on the USP7CD45’s catalytic activity (Figures 2C). A modest effect was observed for L8A, I44A, T66A, L73A and R74A Ub mutants. Notably Q2A, K48A and R72A mutations led to a severe reduction in catalytic efficiency of USP7CD45.

For USP8 catalytic domain (USP8CD) we observed little change in the catalytic efficiency when the Ub mutants Q2A, E64A and L71A were tested. Modest effects were observed for T14A, V70A, L73A, and R74A Ub mutants (Figures 2D). Mutation of L8A, I44A, T66A, and R72A in Ub resulted in severe decreases in catalytic activity. Particularly we observed 58-, 490- and 1000-fold decrease in the catalytic efficiency for K48A, T66A and R72A Ub-AMC respectively.

As a comparison, we also assessed UCH-L1 in deubiquitination using the same panel of mutant Ub-AMC substrates (Figure 2E). Little effect was observed for mutations Q2A, T14A, K48A, E64A, and T66A that are located in the N-terminal region and the body of Ub. A modest decrease was observed for I44A, V70A, R72A and R74A mutations in Ub. Notably L8A, L71A and L73A mutations resulted in severe reduction in the catalytic activity of UCH-L1. Our results are comparable to a previous study that investigated the effect of Ub mutations on the DUB activity of UCH-L1 and UCH-L335.

Double mutant cycle analysis

Next we carried out double mutant cycle analysis by paring Ub residues located in the tip (Q2A), the central body (T66A) and the tail (R74A) of Ub. We sought to determine whether the USP-Ub interactions at the various regions of Ub are additive, synergistic or antagonistic. The change in Gibbs free energy (ΔΔGMut) between the wild-type and mutant Ub was calculated as previously reported using equation 141–43. To determine the energetic crosstalk of the two selected mutations, the coupling free energy ΔGI was calculated by subtracting the sum of the change in Gibbs free energy of the two single mutants (ΔΔGMut1 + ΔΔGMut2) from the change in Gibbs free energy of the double mutant (ΔΔGMut1,2) (eq. 2). A ΔGI close to 0 kcal mol−1 is indicative of an additive effect where the two residues act independently. A positive ΔGI (≥0.1 kcal mol−1) indicates a synergistic effect in which the combined mutations cooperatively decrease the enzymatic activity. On the other hand, a negative ΔGI (≤ −0.1 kcal mol−1) indicates an antagonistic effect where a combination of two mutations results in a partial restoration of enzymatic activity.

The double mutant cycle analysis was first carried out for USP2CD. Interestingly, double mutation Q2A/T66A and Q2A/R74A in Ub had little effect on the catalytic efficiency of USP2 in deubiquitination despite that a modest reduction in catalytic efficiency was observed for the respective single Ub mutant T66A and R74A. The calculated ΔGI was −1.1 and −0.82 kcal mol−1 for Q2A/T66A and Q2A/R74A respectively (Table 1, Figure 3 and S1) suggesting an antagonistic effect in the two pairs of Ub mutations. In marked difference, double mutant cycle analysis of T66A/R74A Ub revealed an additive effect with ΔGI = 0.07 kcal mol−1, suggesting little functional interaction between T66 and R74 in the deubiquitination by USP2CD.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of USP2CD and USP21CD with double mutant ubiquitin.

| Enzyme | Ub-AMC | kcat/Km (M−1s−1) | ΔΔG (kcal mol−1) | ΔGI (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP2 | WT | 3.1 × 105 | 0 | |

| Q2A | 1.2 × 105 | 0.56 | ||

| T66A | 5.9 × 104 | 0.98 | ||

| R74A | 6.2 × 104 | 0.95 | ||

| Q2A/T66A | 1.4 × 105 | 0.46 | −1.1 | |

| Q2A/R74A | 9.7 × 104 | 0.69 | −0.82 | |

| T66A/R74A | 1.1 × 104 | 2.0 | 0.07 | |

| USP21 | WT | 2.7 × 105 | 0 | |

| Q2A | 3.4 × 105 | −0.14 | ||

| T66A | 2.3 × 105 | 0.094 | ||

| R74A | 7.7 × 104 | 0.74 | ||

| Q2A/T66A | 2.2 × 104 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| Q2A/R74A | 1.1 × 105 | 0.53 | −0.07 | |

| T66A/R74A | 4.2 × 104 | 1.1 | 0.27 |

Figure 3.

Heat map showing the catalytic efficiency of USP2CD, USP7CD45, USP8CD, USP21CD, and UCH-L1 hydrolyzing the wild-type and mutant Ub-AMC. Ub mutations with little decrease (<5-fold) in catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) are shown as green, modest decrease (5 to 50-fold) shown as yellow, and severe decrease (>50-fold) shown as orange. Ubiquitin mutations that resulted in a loss of detectable activity are shown as red.

The same double mutant cycle analysis was also carried out for USP21CD (Table 1, Figure 3 and S2). Notably USP21 differs from USP2 in that a synergistic effect was observed for Q2A/T66A and T66A/R74A (ΔGI = 1.5 and 0.27 kcal mol−1 respectively), and an additive effect was observed for Q2A/R74A (ΔGI of −0.07 kcal mol−1).

For USP7CD45 we were unable to detect catalytic turnover for Q2A/T66A Ub (Figure 3 and S3). Since Ub mutant Q2A resulted in a severe decrease in catalytic efficiency whereas a modest decrease was observed for T66A, it is difficult to determine the relationship between Q2A and T66A mutations as the activity is below detection limit. Nonetheless we were able to determine a synergistic relationship for Q2A/R74A (ΔGI of 0.1 kcal mol−1) and an antagonistic relationship for T66A/R74A mutations (ΔGI of −0.1 kcal mol−1).

In the case of USP8CD, we were unable to detect the activity of double mutants Q2A/T66A and T66A/R74A. The single mutant T66A resulted in a severe decrease in USP8CD’s catalytic efficiency by 920-fold. We rationalize that either an additive or synergistic relationship would reduce USP8CD’s catalytic activity beyond the detection limit. For Q2A/R74A we were able to measure the ΔGI of 1.3 kcal mol−1 indicating a synergistic relationship in USP8CD catalysis (Figure 3 and S4).

The role of zinc binding in USP catalysis

Many but not all USPs contain a zinc ribbon located at the fingertip of the USP finger subdomain. The exact role of zinc binding in USP function and catalysis is not fully understood. An inspection of the available USP7 and USP8 apo-structures revealed difference in the rigidity of the fingertip in USPs depending on whether or not a functional zinc ribbon is present in the USP structure. B-factor analysis indicated that the loops in the USP7 fingertip are highly flexible in the apo-structure as compared to other regions in USP7, (Figure S5A). In contrast the loops of the zinc ribbon in the USP8 apo-structure is more rigid (Figure S5B). Since the zinc ribbon is located at the fingertip of USP finger domain that interacts with Ub, it is possible that the restraint of the fingertip loops is beneficial to Ub binding. To determine the effect of zinc binding on the USP catalytic activity, we generated C476S/C479S USP2CD (ZnKO USP2CD), C985S/988S USP8CD (ZnKO USP8CD) and C437S/C440S USP21CD (ZnKO USP21CD) knocking out the zinc binding to the finger subdomain. The yield of ZnKO USP2CD was approximately 25% of the wild-type USP2CD. ZnKO USP8CD and ZnKO USP21CD were found to be largely insoluble, which suggests that the zinc binding may play a structural role in some USPs.

In order to confirm that ZnKO USP2 no longer possessed zinc binding capacity, we determined the zinc content of the wild-type and mutant USP2 as described in Methods. In the case of the wild-type USP2CD we determined that approximately one zinc ion was bound to USP2CD (Figure 4A). Our results were in agreement with a single zinc ion binding to the zinc ribbon in the USP2 finger subdomain as suggested by the crystal structure17. We next assayed the zinc binding of ZnKO USP2 and found no significant zinc binding (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Zinc binding and kinetic analysis of USP2CD and USP7CD. (A) Zinc binding capacity of wild-type (red) and zinc knockout (blue) USP2CD. The zinc depleted HNG buffer (black) was used as a control. Molar concentration of zinc ion was determined by Zn2+(PAR)2 complex formation and monitored at 500 nm. (B) Enzyme kinetics of 1 nM wild-type USP2CD. (C) Enzyme kinetics of 10 nM C476S/C479S USP2CD. (D) Zinc binding capacity of wild-type USP7CD (red) and zinc knock-in USP7CD (blue). The zinc depleted HNG buffer (black) was used as a control. (E) Enzyme kinetics of 100 nM wild-type USP7CD. (F) Enzyme kinetics of 100 nM V337C/A381C/H384C USP7CD.

We then compared the enzymatic activity of the ZnKO USP2CD and the wild-type USP2CD to determine the effect of zinc binding on catalysis. ZnKO USP2CD displayed reduced enzymatic activity as a result of increased Km from 1.8 µM to 26 µM (Figure 4B and C) whereas kcat was increased by only 2-fold (0.55 to 1.3 s−1). It has been previously determined that for USP2CD Km is comparable to Kd40. Our measurement suggested a reduction in ZnKO USP2CD’s Ub binding capacity. Our results support the notion that the zinc ribbon motif is required for efficient enzymatic activity of certain members of the USP family as exemplified by USP2.

After determining that USP2CD zinc knockout resulted in a clear decrease in catalytic efficiency, we asked whether introducing a zinc binding motif at the fingertip of USP structure could increase catalytic efficiency. Of the USPs tested, USP7 does not contain the zinc ribbon motif. A bioinformatics study suggested that USP7 lost its zinc binding capacity through mutation of three cysteine residues to Val337, Ala381 and His38436. We mutated USP7CD to introduce the CXXC zinc ribbon motif as found in USP2. Using a zinc binding assay, we confirmed that zinc binding was introduced to USP7CD (Figure 4D). Next we compared the catalytic activity of the wild-type USP7CD to the zinc knock-in mutant (Figure 4E and F). For the zinc ribbon knock-in the Km remained largely unchanged (1.4 versus 1.2 µM for the wild-type and mutant USP7CD respectively) whereas kcat was slightly increased from 0.007 s−1 (wild-type USP7CD) to 0.029 s−1 (mutant USP7CD). Catalytic efficiencies of zinc knock-in (2.4 × 104 M−1s−1) was increased slightly by 4.8 fold compared to the wild-type USP7CD (5.0 × 103 M−1s−1), suggesting that USP7CD does not greatly benefit from the zinc ribbon motif.

Discussion

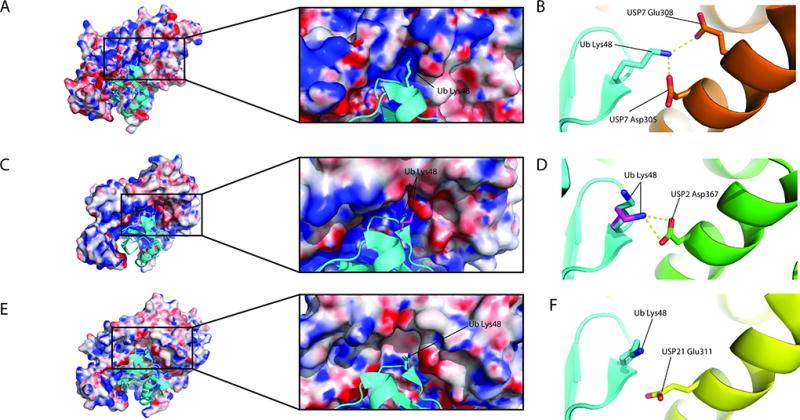

Our mutation analysis revealed that despite the conserved catalytic domain structure of USPs, many Ub residues differ substantially in contribution to Ub binding and deubiquitination among the USP family DUBs. As revealed by the heat map generated based on the catalytic efficiency of DUBs measured using a panel of mutant Ub-AMC (Figure 3), a number of Ub residues, including charged, polar and hydrophobic residues, are uniquely required for the catalysis of the tested USPs. These residues, found in the Ub tip, central body and tail, mark a number of hot spots on the interacting USP that contribute to the binding of Ub and USP catalysis. Notably, most of the hot spots on USPs are relatively flat except one that engages the Lys48 on Ub and a second one where Ub Leu73 binds. As best exemplified in the USP7CD-Ub cocrystal structure, the Ub Lys48 side chain binds to a pocket formed by Tyr348, Leu304, Asp305, Glu308 and Arg301, which we named ‘Lys48 pocket’. The side-chain amine group of Ub Lys48 forms hydrogen bond and salt bridge with the USP7 Asp305 and Glu308 in a bidentate conformation (Figure 5A and B) as identified by the program PISA45–47. This may explain the large impact on USP7CD deubiquitination when the Ub Lys48 was mutated to Ala. In contrast USP2CD and USP21CD showed little decrease in the catalytic efficiency with the K48A Ub mutant. An inspection of the position of Ub Lys48 in the two available USP2-Ub complex structures revealed two markedly different conformations (Figure 5C). In one complex structure (PDB ID 3NHE), the Lys48 side chain amine forms a hydrogen bond with the USP2 Asp367 side chain carboxylate (Figure 5D), while in the second complex structure with higher resolution (PDB ID 2HD5) the Ub Lys48 adopts a different side chain conformation without engagement in hydrogen bond or salt bridge (Figure 5D). Notably in the two available USP21-Ub complex structures (PDB ID 2Y5B and 3I3T), no hydrogen bond or salt bridge was identified between the Ub Lys48 and USP21 residues as revealed by an analysis with PISA (Figure 5E and F). In the USP2 and USP21 complex structure, the side chain of Ub Lys48 does not occupy the nearby pocket on USP (see Figure 5C and 5E). By overlaying the USP7 apo-structure and the USP7 structure in complex with Ub we found that the ‘Lys48 pocket’ exists in the USP7 apo-structure and is enlarged due to the movement of the USP7 Arg301 side chain (see Figure S6A and B). We also overlaid the USP8 apo-structure to the USP7 apo-structure and did not find an equivalent pocket in the USP8 apo-structure (Figure S6C). Since the apo-structure of USP2 and USP21 are not currently available we cannot assess the ‘Lys48 pocket’ in these two USPs in comparison to the USP7 apo-structure. However, the difference in the kinetics of deubiquitination in response to Ub K48A mutation and the difference in the Ub K48 binding to USPs in the Ub-USP complex structures suggest that a small molecule that binds to the Lys48 pocket may allow certain degree selectivity of inhibiting USP7. Future structural determination of other USPs in the apo- and complex-forms will provide a better idea of the divergence in the above described USP Lys48 pocket and allow development of selective USP inhibitors.

Figure 5.

The different interactions of Ub Lys48 side chain with USPs as revealed by the USP-Ub complex structures. Surface structures are represented by their electrostatic potential represented as red (negatively charged), white (neutral/hydrophobic), and blue (positively charged). (A) USP7 (PDB 1NBF) in complex with Ub (cyan). The zoomed-in view shows the pocket that Ub Lys48 binds to. (B) Ub Lys48 forms a bidentate interaction with USP7 Asp305 and Glu308 (orange). (C) USP2-Ub complex structures reveal two conformations of Ub Lys48. (D) Ub Lys48 (magenta) in USP2-Ub complex structure (PDB 3NHE) forms a hydrogen bond with USP2 Asp367. However, Ub Lys48 (cyan) in the USP2-Ub complex structure (PDB 2HD5) forms no hydrogen bond with USP2 residue. (E) USP21 (PDB 3I3T) in complex with ubiquitin (cyan). (F) USP21 Glu311 (yellow), which is structurally aligned to USP7 Asp305 and USP2 Asp367, does not form a hydrogen bond with Ub Lys48.

Another pocket on USP located closer to the active site was found to accommodate the Ub Leu73 residue, hence named ‘Leu73 pocket’ (Figure 6D–F). Our kinetics analysis of the L73A Ub-AMC mutant also revealed divergence in the tolerance of the USPs to the Ub C-terminal mutation. A comparison of the pockets showed that despite that they are of similar size the residues that line the pocket and the rim are divergent (Figure D–F). This suggests that small molecules that bind specifically to the USP ‘Leu73 pocket’ may be possible.

Figure 6.

Interactions of Ub Leu73 and Lys6 with USPs. Ub is colored cyan. USP surface is colored according to the type of atoms: carbon (green), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue) and sulfur (yellow). Ub Leu73 binds to a pocket in USP2 (A), USP7 (B), and USP21 (C). Ub Lys6 interacts with USP2 (D), USP7 (E), and USP21 (F) with no pocket identified.

Recently several Ub lysine residues, particularly Lys6 and Lys48, were found to be acetylated in cells48,49. Given that acetylation of Lys48 removes the positive charge on the lysine chain, we speculate that Ub Lys48 acetylation may also play a role in regulating the DUB activity of certain USPs, such as USP7, in which Lys48 engages in an interaction with the USP catalytic core domain through salt bridge and hydrogen bond. Notably, Lys6 and Lys48 acetylation on Ub was found to affect the discharge of the Ub onto target protein in several E2 proteins48. Therefore, it will be of interest to determine the effect of Ub Lys48 acetylation on the deubiquitination by the various USPs.

In addition to acetylation, Lys48 on Ub is often modified by the C-terminal carboxylate of a distal Ub to form Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chain. As a result, the positive charge of the lysine side chain is removed and a bulky Ub moiety is added, which likely affects the interaction between Ub Lys48 and the USPs as observed in the USP7 complex structure. Thus the interaction of Ub Lys48 with USP surface residues suggests a potential mechanism of chain linkage discrimination when an endocleavage is operational in the USPs. At present how USPs cleave Ub chain through either an endo- or exo-cleavage mode is not well-defined. Future investigation into this problem will help to better understand the role of the Ub Lys48 interaction in determining the chain linkage specificity.

Ub possesses a hydrophobic patch consisting of Il44, Leu8 and Leu70, that has been found to be the main interaction site with many Ub binding domains, including UIM, UBZ34. We also assessed the contribution of the hydrophobic residues on Ub to USP catalysis. Similar to the selected charged residues on Ub, clear divergence was also observed for the Ub hydrophobic residues. We attempted to rationalize the difference observed for the hydrophobic interactions using the software PISA45–47. Our analyses did not reveal large differences in the solvation energy effect of the individual Ub hydrophobic residues upon binding to the tested USPs. In most cases well-defined hydrophobic patch on USP that is close to the Ub hydrophobic residues was not obvious in an analysis using LigPlot+50,51. This is in accord with the relatively weak hydrophobic interaction as suggested by the PISA analysis (0.5— 0.7 kcal mol−1). In view of the weak hydrophobic interactions, it is possible that other factors may contribute to the divergence of the USP catalysis with the mutation of the hydrophobic residues on Ub. Indeed, one of the hydrophobic residues on Ub, Leu8, is located in the Ub β1–β2 loop. A recent study by Phillips et al. revealed a conformational dynamics of the Ub β1–β2 loop52. They found that the conformation of the Ub β1–β2 loop is important for the Ub binding to USP14. An inspection of the Ub structure in the complex with USP2CD and USP7CD, the Ub Leu8 forms a hydrophobic interaction with the Ub residues Ile36, Leu69, and Leu71 which helps to position the β1–β2 loop into a conformation that is similar to that observed in USP14-Ub structure (Figure S7). It is possible that upon mutating Leu8 to Ala in Ub, the absence of the hydrophobic interaction shifts the conformation of the β1–β2 loop in Ub and reduced its binding to USP7 and USP2. Our results support the important role of the Ub β1–β2 loop in USP catalysis. Interestingly, we did note an exception, USP21CD, that displayed a small decrease in catalytic efficiency with the Ub L8A mutation (Figure 2B and 3). This may be attributed to the intrinsic property of USP21CD binding Ub that it possesses a much lower Km with Ub-AMC substrate compared to other USPs22. Further studies will be needed for a better understanding of the molecular basis underlying the divergence of the hydrophobic interactions between Ub and USPs.

Our study also revealed interesting roles of zinc that binds to the fingertip of the USP finger subdomain in USP catalysis. First the zinc ion likely promotes and stabilizes the folding of USP. Mutating the zinc binding residues in USP8CD and USP21CD led to insoluble proteins when expressed in E. coli and also reduced yield for USP2CD. Second the zinc binding may play an indirect role in Ub binding to USPs by positioning the fingertip residues for interaction with the Ub residues particularly Gln2 (Figure 7A—C). The fact that USP7 lacks the zinc binding residues at the fingertip and a zinc-binding knock-in mutant showed only a small improvement to the USP7 catalysis argues that the USP7 sequence has been optimized through evolution to support a stable conformation of the fingertip region without the need of zinc binding. However, our observation that Ub Q2A mutation led to a severe decrease in USP7 catalysis but not the other tested USPs suggests that the interaction of the USP fingertip with the Ub residues particularly Gln2 is necessary for a functional conformation of the fingertip, but only in the absence of zinc binding. This is evident in an overlay of the USP7 apo- and complex-structures showing a clear structural rearrangement of a USP7 loop (a.a. 373LDGDNKDAGEHG385) at the fingertip upon the binding of Ub. Notably the distance between the Ub Gln2 side chain amide amino group and the USP7 Lys378 backbone carbonyl oxygen is 2.9 Å in the complex structure, while in the overlaid USP7 apo-structure the distance is 3.4 Å (Figure 7D). The shorter distance allows a bidentate interaction between Ub Gln2 and the backbone amide of USP7 Asp380 and Lys378 (Figure 7E). In addition, the Ub Thr14 also form hydrogen bonds with USP7 Asn377 (Figure 7E). Our mutational studies suggest a more important role of Ub Gln2 in interactions with USP7.

Figure 7.

Interaction of the USP fingertip region with ubiquitin. (A) An overlay of USP2 (PDB 2HD5, green) and USP7 (PDB 1NBF, orange) using the Ub (cyan) in the two USP-Ub complexes. The USP zinc ribbon is located at the “tip” of the finger subdomain (boxed in the figure). (B) USP2 zinc ribbon contains a zinc ion coordinated by four cysteines. (C) USP7 lacks zinc ribbon and contains Val337, Ala381, and His384 instead of the cysteine residues found in USP2. (D) A loop that is adjacent to the USP7 fingertip (a.a. 373LDGDNKDAGEHG385) changes its position upon Ub binding. (E) Hydrogen bonds between the USP7 fingertip region and Ub Gln2 and Thr14 in the USP7-Ub complex.

As revealed by sequence analysis, many USPs contain a full zinc-ribbon motif that is capable of binding a zinc ion. This raises an intriguing possibility of the regulation of USP catalysis by cellular redox environment. Indeed, oxidation of zinc binding cysteines, such as those found in the zinc ribbons, are known to act as a redox sensor in cells53. For example, the SP-1 family of DNA binding proteins are regulated by the oxidation of their zinc finger cysteines54. Additionally, the binding of transcription factor Egr-1 to DNA is disrupted when its zinc finger cysteines are oxidized55. Oxidative stress causes the zinc ribbon cysteines to form disulfide bonds, hence abolishing the zinc binding. Thus disruption of zinc binding might reduce Ub binding similar to what we observed with the zinc-binding knockout USP2CD mutant.

In addition to the hydrophobic residues in the Ub tail, two positively charged Arg residues, Arg72 and Arg74, were also assessed in their contribution to USP catalysis. Among the Ub residues investigated in this study, the R72A mutation was found to elicit the most pronounced effect in all four tested USPs. An inspection of the available USP7-Ub complex structure revealed an interaction between the Ub Arg72 and a conserved Glu in USPs (Figure 8A). In the USP7-Ub complex structure, Glu298 (PDB 1NBF) is located at the N-terminal end of an α-helix. Its position is shifted upon Ub binding, which in turn repositions the catalytic cysteine located on a neighboring α-helix (Figure 8B). Notably Faesen et al. identified a “switching loop” corresponding to the amino acids 285—291 in USP7 that contributes to the activation of USP7’s DUB activity through an interaction with the USP7 C-terminal Ub-like domain 4 & 5 (HUBL-45)16. The interaction between Ub Arg72 and the conserved Glu (Glu298 in USP7) that we identified may provide an allosteric path that regulates the active site conformation in USP7. And this pair of interaction between Ub Arg72 and the equivalent Glu may serve as a molecular switch of catalytic activity of some USPs. We also noticed that this interaction appears to be more crucial for the catalysis by USP7 (Glu298) and USP8 (Glu871, PDB 2GFO) compared to USP2 (Glu360, PDB 2HD5) and USP21 (Glu304, PDB 3I3T). We speculate that the reliance on the interaction between the Ub Arg72 and the conserved USP Glu residue may depend on the conformational plasticity of the USP active sites. USP7 harbors an active site that is conformationally flexible, as supported by the marked difference between the apo- and complex-structures of USP715,16. For USP2, USP8, and USP21 such a comparison is not yet possible due to the lack of either apo- or complex-structures. Notably Ye et al. reported that mutation of USP21 Glu304 to alanine resulted in a decrease in USP21’s catalytic turnover of Ub-AMC and polyubiquitin chain, supporting an important role of the conserved Ub Arg72-USP glutamate interaction in USP catalysis22. Future structural elucidation of the USP-Ub complexes will shed more light on the allosteric pathways that regulate the USP catalysis.

Figure 8.

Interaction of Ub Arg72 with USPs. (A) Ub Arg72 forms a hydrogen bond with a conserved glutamate in USP2 (PDB 2HD5, green), USP7 (PDB 1NBF, orange), USP8 (PDB 2GFO, magenta), and USP21 (PDB 3I3T, yellow) complex structures. (B) Binding of Ub Arg72 to USP7 (apo shown in grey, PDB 1NB8) may promote conformational changes that reposition the active site Cys223 to a catalytically competent conformation (orange).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yu Peng for the help of generating mutant Ub-AMC. We thank Dr. Sirano Dhe-Pagano for providing us with the USP8 expression vector. We also would like to thank Dr. Cheryl Arrowsmith for the USP21 expression vector deposited in Addgene (3MTN). We thank Christine Ott for careful reading the manuscript and the useful input.

Funding

The work was supported by a NIH grant (R01GM097468) to Z. Zhuang.

References

- 1.Chen ZJ, Sun LJ. Nonproteolytic Functions of Ubiquitin in Cell Signaling. Molecular Cell. 2009;33:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbé S. Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2009;10:550–563. doi: 10.1038/nrm2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shembade N, Harhaj E. Regulation of NF-κB signaling by the A20 deubiquitinase. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:123–130. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu H, Brittain G, Chang J-H, Puebla-Osorio N, Jin J, Zal A, Xiao Y, Cheng X, Chang M, Fu Y-X, Zal T, Zhu C, Sun S-C. OTUD7B controls non-canonical NF-κB activation through deubiquitination of TRAF3. Nature. 2013;494:371–374. doi: 10.1038/nature11831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Zhao X, Zhang M, Zhao W, Gao C. Ubiquitin-specific protease 2b negatively regulates IFN-2 production and antiviral activity by targeting TANK-binding kinase 1. Journal of immunology. 2014;193:2230–2237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satoh T, Sumiyoshi A, Yagi-Utsumi M, Sakata E, Sasakawa H, Kurimoto E, Yamaguchi Y, Li W, Joazeiro C, Hirokawa T, Kato K. Mode of substrate recognition by the Josephin domain of ataxin-3, which has an endo-type deubiquitinase activity. FEBS Letters. 2014;588:4422–4430. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raposo M, Bettencourt C, Maciel P, Gao F, Ramos A, Kazachkova N, Vasconcelos J, Kay T, Rodrigues A, Bettencourt B, Bruges Armas J, Geschwind D, Coppola G, Lima M. Novel candidate blood based transcriptional biomarkers of machado joseph disease. Movement Disorders. 2015;30:968–975. doi: 10.1002/mds.26238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao R, Liu Y, Silva-Fernandes A, Fang X, Paulucci-Holthauzen A, Chatterjee A, Zhang HL, Matsuura T, Choudhary S, Ashizawa T, Koeppen AH, Maciel P, Hazra TK, Sarkar PS. Inactivation of PNKP by Mutant ATXN3 Triggers Apoptosis by Activating the DNA Damage-Response Pathway in SCA3. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11:e1004834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bingol B, Tea JS, Phu L, Reichelt M, Bakalarski CE, Song Q, Foreman O, Kirkpatrick DS, Sheng M. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature. 2014;510:370–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelissen T, Haddad D, Wauters F, Humbeeck C, Mandemakers W, Koentjoro B, Sue C, Gevaert K, Strooper B, Verstreken P, Vandenberghe W. The deubiquitinase USP15 antagonizes Parkin-mediated mitochondrial ubiquitination and mitophagy. Human Molecular Genetics. 2014;23:5227–5242. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durcan TM, Tang MY, Pérusse JRR, Dashti EA, Aguileta MA, McLelland G-LL, Gros P, Shaler TA, Faubert D, Coulombe B, Fon EA. USP8 regulates mitophagy by removing K6-linked ubiquitin conjugates from parkin. The EMBO journal. 2014;33:2473–2491. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graner E, Tang D, Rossi S, Baron A, Migita T, Weinstein LJ, Lechpammer M, Huesken D, Zimmermann J, Signoretti S, Loda M. The isopeptidase USP2a regulates the stability of fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;5:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Zanata, Kim Peterson, Vizio D, Chirieac Pyne, Agostini Freeman, Loda The ubiquitin-specific protease USP2a prevents endocytosis-mediated EGFR degradation. Oncogene. 2012;32:1660–1669. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhi Y, ShouJun H, Yuanzhou S, Haijun L, Yume X, Kai Y, Xianwei L, Xueli Z. STAT3 repressed USP7 expression is crucial for colon cancer development. FEBS Letters. 2012;586:3013–3017. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu M, Li P, Li M, Li W, Yao T, Wu J-W, Gu W, Cohen RE, Shi Y. Crystal Structure of a UBP-Family Deubiquitinating Enzyme in Isolation and in Complex with Ubiquitin Aldehyde. Cell. 2002;111:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faesen A, Dirac A, Shanmugham A, Ovaa H, Perrakis A, Sixma T. Mechanism of USP7/HAUSP Activation by Its C-Terminal Ubiquitin-like Domain and Allosteric Regulation by GMP-Synthetase. Molecular Cell. 2011;44:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renatus M, Parrado S, D’Arcy A, Eidhoff U, Gerhartz B, Hassiepen U, Pierrat B, Riedl R, Vinzenz D, Worpenberg S, Kroemer M. Structural Basis of Ubiquitin Recognition by the Deubiquitinating Protease USP2. Structure. 2006;14:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clerici M, Luna-Vargas M, Faesen A, Sixma T. The DUSP–Ubl domain of USP4 enhances its catalytic efficiency by promoting ubiquitin exchange. Nature Communications. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avvakumov GV, Walker JR, Xue S, Allali-Hassani A, Asinas A, Nair UB, Fang X, Zuo X, Wang Y-X, Wilkinson KD, Dhe-Paganon S. Two ZnF-UBP Domains in Isopeptidase T (USP5) Biochemistry. 2012;51:1188–1198. doi: 10.1021/bi200854q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avvakumov G, Walker J, Xue S, Finerty P, Mackenzie F, Newman E, Dhe-Paganon S. Amino-terminal Dimerization, NRDP1-Rhodanese Interaction, and Inhibited Catalytic Domain Conformation of the Ubiquitin-specific Protease 8 (USP8) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:38061–38070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu M, Li P, Song L, Jeffrey P, Chernova T, Wilkinson K, Cohen R, Shi Y. Structure and mechanisms of the proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzyme USP14. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24:3747–3756. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye Y, Akutsu M, Reyes-Turcu F, Enchev RI, Wilkinson KD, Komander D. Polyubiquitin binding and cross-reactivity in the USP domain deubiquitinase USP21. EMBO reports. 2011;12:350–357. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin J, Schoeffler AJ, Wickliffe K, Newton K, Starovasnik MA, Dueber EC, Harris SF. Structural Insights into WD-Repeat 48 Activation of Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 46. Structure (London, England: 1993) 2015;3:2043–2054. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato Y, Goto E, Shibata Y, Kubota Y, Yamagata A, Goto-Ito S, Kubota K, Inoue J, Takekawa M, Tokunaga F, Fukai S. Structures of CYLD USP with Met1- or Lys63-linked diubiquitin reveal mechanisms for dual specificity. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2015;22:222–229. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komander D, Lord CJ, Scheel H, Swift S, Hofmann K, Ashworth A, Barford D. The Structure of the CYLD USP Domain Explains Its Specificity for Lys63-Linked Polyubiquitin and Reveals a B Box Module. Molecular Cell. 2007;29:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misaghi S, Galardy PJ, Meester WJ, Ovaa H, Ploegh HL, Gaudet R. Structure of the Ubiquitin Hydrolase UCH-L3 Complexed with a Suicide Substrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:1512–1520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston SC, Riddle SM, Cohen RE, Hill CP. Structural basis for the specificity of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases. The EMBO Journal. 1999;18:3877–3887. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Messick T, Russell N, Iwata A, Sarachan K, Shiekhattar R, Shanks JR, Reyes-Turcu FE, Wilkinson KD, Marmorstein R. Structural Basis for Ubiquitin Recognition by the Otu1 Ovarian Tumor Domain Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:11038–11049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704398200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies CW, Paul LN, Kim M-I, Das C. Structural and Thermodynamic Comparison of the Catalytic Domain of AMSH and AMSH-LP: Nearly Identical Fold but Different Stability. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2011;413:416–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrestha R, Ronau J, Davies C, Guenette R, Strieter E, Paul L, Das C. Insights into the Mechanism of Deubiquitination by JAMM Deubiquitinases from Cocrystal Structures of the Enzyme with the Substrate and Product. Biochemistry. 2014;53:3199–3217. doi: 10.1021/bi5003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicastro G, Masino L, Esposito V, Menon R, Simone A, Fraternali F, Pastore A. Josephin domain of ataxin-3 contains two distinct ubiquitin-binding sites. Biopolymers. 2009;91:1203–1214. doi: 10.1002/bip.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato Y, Yoshikawa A, Yamagata A, Mimura H, Yamashita M, Ookata K, Nureki O, Iwai K, Komada M, Fukai S. Structural basis for specific cleavage of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitin chains. Nature. 2008;455:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature07254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faesen AC, Luna-Vargas M, Sixma TK. The role of UBL domains in ubiquitin-specific proteases. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2012;40:539–545. doi: 10.1042/BST20120004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurley JH, Lee S, Prag G. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochemical Journal. 2006;399:361–372. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luchansky SJ, Jr, P T, Stein RL. Substrate Recognition and Catalysis by UCH-L1. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14717–14725. doi: 10.1021/bi061406c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishna SS, Grishin NV. The finger domain of the human deubiquitinating enzyme HAUSP is a zinc ribbon. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 2004;3:1046–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hetfeld B, Helfrich A, Kapelari B, Scheel H, Hofmann K, Guterman A, Glickman M, Schade R, Kloetzel P-M, Dubiel W. The Zinc Finger of the CSN-Associated Deubiquitinating Enzyme USP15 Is Essential to Rescue the E3 Ligase Rbx1. Current Biology. 2005;15:1217–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernst A, Avvakumov G, Tong J, Fan Y, Zhao Y, Alberts P, Persaud A, Walker JR, Neculai A-MM, Neculai D, Vorobyov A, Garg P, Beatty L, Chan P-KK, Juang Y-CC, Landry M-CC, Yeh C, Zeqiraj E, Karamboulas K, Allali-Hassani A, Vedadi M, Tyers M, Moffat J, Sicheri F, Pelletier L, Durocher D, Raught B, Rotin D, Yang J, Moran MF, Dhe-Paganon S, Sidhu SS. A strategy for modulation of enzymes in the ubiquitin system. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013;339:590–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1230161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Zhou L, Rouge L, Phillips A, Lam C, Liu P, Sandoval W, Helgason E, Murray J, Wertz I, Corn J. Conformational stabilization of ubiquitin yields potent and selective inhibitors of USP7. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9:51–58. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bozza WP, Liang Q, Gong P, Zhuang Z. Transient Kinetic Analysis of USP2-Catalyzed Deubiquitination Reveals a Conformational Rearrangement in the K48-Linked Diubiquitin Substrate. Biochemistry. 2012;51:10075–10086. doi: 10.1021/bi3009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mildvan A, Weber D, Kuliopulos A. Quantitative interpretations of double mutations of enzymes. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1992;294:327–340. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90692-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sohn J, Rudolph J. The Energetic Network of Hotspot Residues between Cdc25B Phosphatase and its Protein Substrate. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;362:1060–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajagopalan RP, Lutz S, Benkovic SJ. Coupling Interactions of Distal Residues Enhance Dihydrofolate Reductase Catalysis: Mutational Effects on Hydride Transfer Rates†. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12618–12628. doi: 10.1021/bi026369d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ai Y, Wang J, Johnson RE, Haracska L, Prakash L, Zhuang Z. A novel ubiquitin binding mode in the S. cerevisiae translesion synthesis DNA polymerase η. Molecular BioSystems. 2011;7:1874–1882. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00355g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krissinel E. Crystal contacts as nature’s docking solutions. Journal of computational chemistry. 2010;31:133–143. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Detection of protein assemblies in crystals. Computational Life Sciences 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. Journal of molecular biology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtake F, Saeki Y, Sakamoto K, Ohtake K, Nishikawa H, Tsuchiya H, Ohta T, Tanaka K, Kanno J. Ubiquitin acetylation inhibits polyubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO reports. 2015;16:192–201. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein engineering. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laskowski RA, Swindells MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips AH, Zhang Y, Cunningham CN, Zhou L, Forrest WF, Liu PS, Steffek M, Lee J, Tam C, Helgason E, Murray JM, Kirkpatrick DS, Fairbrother WJ, Corn JE. Conformational dynamics control ubiquitin-deubiquitinase interactions and influence in vivo signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:11379–11384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302407110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maret W. Zinc coordination environments in proteins as redox sensors and signal transducers. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2006;8:1419–1441. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu X, Bishopric NH, Discher DJ. Physical and functional sensitivity of zinc finger transcription factors to redox change. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1996;16:1035–1046. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang R, Adamson ED. Characterization of the DNA-binding properties of the early growth response-1 (Egr-1) transcription factor: evidence for modulation by a redox mechanism. DNA and cell biology. 1993;12:265–273. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.