Abstract

The aim of this prospective, longitudinal study was to examine the association between couples’ pre-treatment psychological characteristics (state anxiety and infertility-related stress levels of both partners) and ovarian response during assisted reproductive technology treatment in a well-controlled sample. A total of 217 heterosexual couples (434 patients), suffering from primary infertility and undergoing their first assisted reproductive technology treatment at the Reproductive Medicine Unit of ANDROS Day Surgery Clinic in Palermo (Italy), were recruited. Psychological variables were assessed using the State Scale of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) and the Fertility Problem Inventory (FPI). The number of follicles ≥ 16 mm in diameter, evaluated by transvaginal ultrasound scan on the eleventh day of the workup, was chosen as the outcome measure. No association between women’s level of anxiety and infertility-related stress, and the number of follicles ≥ 16 mm in diameter was found. Moreover, the male partner’s infertility stress and anxiety did not influence the relationship between the woman’s infertility-related stress, anxiety level and ovarian response. Fertility staff should reassure couples that the woman’s biological response to ovarian stimulation is not influenced by either partner’s level of psychological distress.

Keywords: anxiety effects, assisted reproductive technology outcome, infertility-related stress, ovarian response

Introduction

Between 9 and 15% of the childbearing population experience infertility (Boivin et al., 2007) and 55% of infertile couples request treatment using assisted reproductive technology to address the issue (Bunting and Boivin, 2007). According to Boivin et al. (2011), many couples experiencing infertility believe that stress or anxiety contribute to the outcome of fertility treatment. A considerable literature has accumulated regarding the association of psychological distress with assisted reproductive technology outcome, and several hypotheses have also been put forward to account for the reasons why psychosocial factors and an individual’s level of distress could be associated with the assisted reproductive technology treatment outcome. One hypothesis is that activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis during stress interferes with the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulse generator, the activity of which is required to cause a cascade of other hormonal events that undermine the reproductive function (Ferin, 1999, Lancastle and Boivin, 2005). Other proposals include behavioural effects, for example, that stress might trigger or be associated with behaviour or lifestyle decisions that may then compromise fertility (Boivin and Schmidt, 2005, Waylen et al., 2009).

Although much research has been conducted into the influence on outcome of psychological factors related to IVF and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), the results are still inconclusive. For example, Smeenk et al. (2001) found a significant relationship between a composite baseline score of state anxiety and depression and a woman’s chance of pregnancy in IVF/ICSI treatment (controlling for age and number of previous pregnancies). Also, Gourounti et al. (2011) found that, having controlled for biomedical factors, infertility-specific stress and anxiety were negatively associated with the chance of pregnancy after IVF in a sample of 160 infertile women. However, two recent meta-analyses do not support these findings. The first meta-analysis (Boivin et al., 2011) included 14 prospective studies, which examined the relationship between pretreatment emotional distress (evaluated through self-report measuring of anxiety, depression and psychological wellbeing) and pregnancy (operationally defined as clinical/preclinical pregnancy or live birth rate) in infertile women undergoing fertility treatment. The findings from this study supported the hypothesis that emotional distress, caused by fertility problems or other life events co-occurring with treatment, does not compromise the possibility of becoming pregnant. However, the authors affirm that definitive research on this link is still lacking. The meta-analysis by Matthiesen et al. (2011) also showed no significant association between depression and clinical pregnancy, and only a slight negative association between stress and clinical pregnancy, and between state or trait anxiety and clinical pregnancy.

The contradictory results from previous research regarding this topic may be due to several methodological shortcomings, in addition to the study design. For example, despite the majority of studies including patients who were undergoing their first IVF/ICSI treatment, as a group the participants are mostly heterogeneous in terms of causes and type of infertility.

In Boivin’s et al. meta-analysis (2011), the main methodological limitations of the studies were the use of convenience samples (non-consecutive or selected samples), failure to fully demonstrate the equivalence of pregnant and non-pregnant groups on prognostic indicators before treatment and the assessment of outcome after a single cycle of treatment with assisted reproductive technology.

It is also worth mentioning that the majority of studies regarding the association between psychological variables and the outcome of IVF/ICSI treatment used the realization of pregnancy as an outcome measure. Pregnancy after IVF/ICSI treatment is the final step in a chain of component events, such as the woman’s response to pharmacological stimulation, the number of follicles obtained, the number and quality of oocytes retrieved, the quality of the sperm, the quality of the embryos and the embryo-transfer procedure. Assessments provided by medical staff, with regard to the quality of oocytes, the development of embryos or the skill of the oocyte retrieval and embryo-transfer operators, may also impact on the ultimate outcome of IVF (Angelini et al., 2006, Karande et al., 1999).

Despite the very early phases of IVF being critical for the outcome, no meta-analyses were conducted (due to the few studies available) to investigate the impact of depression, anxiety and stress on the initial measures (e.g. the number of follicles or oocytes) related to pregnancy outcome (Matthiesen et al., 2011). Several previous studies suggested that a woman’s age, body mass index (BMI), FSH dosage, duration and cause of infertility and number/type of attempts (Broekmans et al., 2014, Rittenberg et al., 2011, Shen et al., 2003) may have an influence on the number of follicles observed during hormonal stimulation. Regarding the influence of a woman’s psychosocial state, a study by Klonoff-Cohen et al. (2001) showed that the number of oocytes retrieved and fertilized, and embryos transferred, decreased with each increase in a woman’s negative affect score on the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) and Profile of Mood States (POMS) scales. Conversely, in the study by Smeenk et al. (2001) there was no relationship between baseline state anxiety (as measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI]) and the number of follicles or oocytes in 291 women undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment. Ebbesen et al. (2009) found that negative life events experienced within the previous 12 months had a bearing on the number of oocytes obtained during oocyte retrieval, whereas there was no effect from perceived current stress, measured by the Perceived Stress Scale, in a sample of 887 Danish women undergoing their first IVF treatment cycle. Moreover, in the Nouri et al. study (2011), women’s stress as measured by saliva and by the Fertility Problem Inventory (FPI; Newton et al., 1999) was not prospectively associated with a reduced number of oocytes in a sample of 83 patients undergoing their first IVF cycle. Interestingly, Lancastle and Boivin (2005) tested a model with a latent psychological factor (whose indicators were dispositional optimism, escapist coping and trait anxiety) to predict the ovarian response dimension (women’s peak oestradiol level, number of follicles and number of oocytes) in a sample of 97 women who were about to begin IVF treatment; this provided evidence for shared variance among the three psychosocial variables and their correlation with women’s ovarian response to stimulation. Taken together, the results from these previous studies do seem inconclusive, and again, several methodological flaws, as well as the clinical heterogeneity of the samples included in these studies, could account for these inconsistent findings.

Finally, there exists a conceptual and analytical problem regarding the previous studies concerning the associations between assisted reproductive technology treatment outcome and psychological characteristics. Infertility is typically experienced by a couple and not by a woman alone. Krasikova and LeBreton’s theory (2012) would suggest that meta-analysis studies are pseudo-unilateral because the researchers do not take into account the anxiety or the infertility stress experienced by the male partner. By analysing data only regarding the woman’s anxiety or infertility stress, researchers are assuming that her partner’s anxiety or infertility stress has no effect on the process of infertility treatment.

Various studies exist highlighting the influence of both partners’ psychological variables with regard to infertility-related stress, anxiety, depression and coping, as experienced by infertile couples undergoing assisted reproductive technology treatment (Benyamini et al., 2009, Donarelli et al., 2012, Martins et al., 2014, Peterson et al., 2008, Peterson et al., 2014); however, to our knowledge, only a few studies (Boivin and Schmidt, 2005, Cooper et al., 2007, Quant et al., 2013) have investigated the impact of both partners’ psychological condition and infertility-related stress on assisted reproductive technology-specific outcomes. For example, in the study by Boivin and Schmidt (2005) higher overall infertility stress, as measured by the Fertility Problem Stress Inventory, in men and women, plus a prolonged period of several years of infertility, was associated with a poorer treatment outcome. These results are limited by the heterogeneous nature of the sample of couples who received IVF, ICSI or intrauterine insemination treatment, and by the definition of the success group (n = 488) and the non-success group (n = 330); the former included both women who were currently pregnant and who had had a live birth, and the latter women who had never been pregnant, alongside those who had reported a pregnancy failure (e.g. miscarriage). In the study by Quant and colleagues (2013) results show that a partner’s higher psychological distress, as measured by the Profile of Mood States and the Life Orientation Test, was negatively associated with the fertilization rate; furthermore, the partner’s depression score was an independent predictor of reduced likelihood of clinical pregnancy following embryo transfer in 100 consecutive couples undergoing IVF treatment.

The aims of the research were twofold: the first was to investigate the link between women’s pre-treatment state anxiety, infertility-related stress (T1 baseline) and ovarian response in their first assisted reproductive technology treatment cycle (T2 outcome). The first hypothesis of the study was that women’s higher scores in infertility-related stress and higher anxiety levels impact negatively on the outcome of ovarian stimulation, after controlling for the duration of infertility, oestradiol levels and total units of gonadotrophins administered.

The second aim was to examine the extent to which the male partner’s infertility stress and anxiety could intervene as a moderating variable in the relationship between a woman’s infertility-related stress and anxiety and her ovarian response. It was postulated that men’s low levels of anxiety and infertility-related stress could reduce the negative effect of their partners’ psychological factors with regard to ovarian stimulation.

Ethical approval

The Research Ethics Committee of the ANDROS Day Surgery Clinic approved the study protocol and all couples were recruited voluntarily; they also gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Materials and methods

Participants

As a part of a larger prospective, longitudinal study, couples had been referred to the Reproductive Medicine Unit of the ANDROS Day Surgery Clinic, Palermo (Italy) between March 2009 and December 2012 for their first assisted reproductive technology treatment. The sample was strictly selected in order to exclude other intervening variables (female cause of infertility, age, basal hormonal values, BMI, past pregnancies, previous treatments), which could affect the outcome.

The inclusion criteria were: (i) primary infertility; (ii) starting initial assisted reproductive technology treatment; (iii) women’s age < 38 years; (iv) women’s BMI ≥ 18 and < 30 kg/m2; (v) women’s FSH values < 12 mIU/ml (measured on cycle day 2-4); and (vi) male factor and unexplained infertility.

Women with female-factor infertility were excluded because their disease could influence ovarian performance. On the other hand, inclusion couples suffering from male-factor and unexplained infertility is based on the knowledge that, in these cases, an impairment of ovarian function may be excluded.

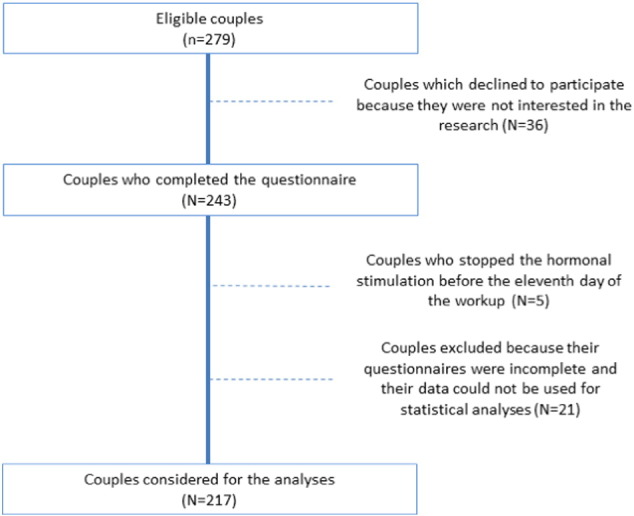

A total of 279 couples (558 subjects), suffering from primary infertility, were consecutively recruited and invited to participate in the research. Thirty-six couples declined to participate due to a lack of interest, and twenty-six couples were subsequently excluded as they had terminated hormonal stimulation prior to the eleventh day of the workup (n = 5) or due to incomplete data (n = 21). The final sample comprised both members of 217 couples, i.e. 77.8% of eligible couples (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Procedure

Participants included in the study were asked to complete questionnaires prior to commencing their initial assisted reproductive technology treatment. The envelope handed to the couples involved in the study, containing only the psychological, standardized and validated self-report measures (one for each female and male partner), was provided by the clinic’s physician. Each partner was asked to separately complete this questionnaire and return it to the physician at the following, scheduled pre-treatment appointment with programme staff (the interval between questionnaire administration and returning the questionnaire was 15-21 days (mean ± SD = 18.5 ± 2.3). The questionnaires (66 items in total) took approximately 15 min to complete.

Controlled ovarian stimulation was performed after pituitary down-regulation, with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist initiated on day 21 of the previous cycle. Multi-follicular development was achieved by daily injections of recombinant FSH, commencing at least 12 days after pituitary down-regulation. Treatment with recombinant FSH was commenced with a 5-day fixed dose regimen and thereafter adjusted, according to the response of the ovaries to stimulation, where necessary. Oestradiol values and follicle growth monitoring (undertaken with the use of transvaginal ultrasonography and measurement of serum oestradiol) were assessed on days 6, 8 and 11 to evaluate possible modifications to the recombinant FSH dosage; for those women who underwent oocyte retrieval, oocyte maturation was triggered with an injection of 10,000 IU of human chorioni gonadotrophin (HCG), after a minimum 10 days of FSH therapy.

Measurements: independent variables (IV)

Infertility-related stress

The FPI was used to measure levels of infertility-related stress. It comprises 46 items covering five domains of infertility-related stress: Social Concerns, Sexual Concerns, Relationship Concerns, Rejection of Childfree Lifestyle and Need for Parenthood. All items are scored using a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (I do not agree) to 6 (I totally agree); the overall score ranges from 46 to 276, where a higher score indicates more fertility-related stress. The FPI demonstrated reliable discriminant and convergent validity (Newton et al., 1999) and adequate psychometric properties with Italian samples (Donarelli et al., 2015). Cronbach’s alpha for the FPI overall score was 0.84 and 0.86 for women and men respectively.

State anxiety

The Italian version of State scale of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) (Pedrabissi and Santinello, 1989, Spielberger et al., 1983) was used to assess participants’ state anxiety. The STAI-S comprises 20 items and it refers to the anxiety level of an individual at a particular moment in time. The score for each item ranges from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety; thus, total scores range from 20 to 80. The STAI-S tool was previously used in infertility research and it has demonstrated a high degree of reliability and validity (e.g. Donarelli et al., 2012, Smeenk et al., 2001). In this study Chronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.83 and 0.86 for women and men respectively.

Measurements: dependent variable (DV)

The DV was the number of follicles equal to or greater than 16 mm in diameter, as evaluated by a transvaginal ultrasound scan on the eleventh day of the workup. It is widely-known that at this measure the follicle should have acquired an adequate number of LH receptors, which are necessary to consent the HCG triggering of oocyte maturation.

Statistical analysis

A preliminary analysis was conducted to verify the normality of data distribution. Cronbach α was computed for all scales in order to determine internal consistency. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation coefficients between variables were also examined.

A three-step regression analysis was performed to verify the direct effect of the women’s infertility-related stress and state anxiety on the ovarian response, and to explore the effect of the interaction between both partner’s infertility-related stress and state anxiety on the same outcome. Only control variables were entered into the model in the first step, i.e. duration of infertility, oestradiol value and total amount of gonadotrophins. Independent variables were entered in the second step: women’s infertility-related stress and state anxiety. Two interaction terms were added to the model in the third step in order to test the hypothesis that the relationship between the women’s stress or anxiety and the ovarian response could differ on the basis of the partner’s stress or anxiety level.

Analyses were performed using PASW Statistical Package software (17.0 version).

Results

Preliminary analyses

A preliminary analysis revealed no substantial violation of normality regarding data distribution (Skewness < 1, Kurtosis < 1). Descriptive analyses demonstrated that women were younger (mean = 33.07, SD = 4.73) than men (men = 36.06, SD = 5.17), and a male cause of infertility was detected in 70% of cases and unexplained factor in 30% of participants; average (± SD) women’s BMI and FSH concentrations were 22.40 (± 2.89) and 6.72 (± 1.98) respectively. Gonadotrophin stimulation was administered for an average (± SD) of 11.94 (± 2.32) days.

Given that no differences were found between partners’ anxiety and infertility-related stress and between the male factor and unexplained infertility groups (data not shown), all the analyses were conducted on the entire sample.

Table 1 shows the descriptive values and correlations for the study variables. Women reported a moderate level of infertility-related stress via the FPI, similar to that reported in previous studies with infertile samples undergoing assisted reproductive technology (Donarelli et al., 2012, Gourounti et al., 2011, Moura-Ramos et al., 2012, Newton et al., 1999). Moreover, both women and men report high levels of state anxiety as significant differences were found between their scores and those of the normative sample (Pedrabissi and Santinello, 1989) (one-sample t-test: t = 2.497, P < 0.05; t = 3.795, P < 0.001 for women and men, respectively).

Table 1.

Descriptive values and correlations of the study variables.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Duration | 3.77 | 2.54 | - | ||||||

| 2 | Oestradiol peak value | 1278.18 | 541.30 | 0.09 | - | |||||

| 3 | Units gonadotropins | 2019.19 | 1127.49 | 0.07 | − 0.10 | - | ||||

| 4 | Women’s anxiety | 41.52 | 9.36 | − 0.11 | − 0.09 | − 0.14* | - | |||

| 5 | Women’s infertility-related stress | 132.81 | 27.77 | 0.03 | 0.02 | − 0.06 | 0.38** | - | ||

| 6 | Men’s anxiety | 38.20 | 8.55 | − 0.01 | − 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.43** | 0.30** | - | |

| 7 | Men’s Infertility-related stress | 129.47 | 26.34 | 0.02 | − 0.01 | − 0.07 | 0.24** | 0.69** | 0.48** | - |

| 8 | No. of follicles > 16 mm | 6.35 | 2.47 | − 0.13 | 0.25** | − 0.22** | 0.01 | 0.02 | − 0.03 | − 0.09 |

* P < 0.05; ** P < = 0.01.

Results show that oestradiol values were positively associated with the number of follicles equal to or greater than 16 mm in diameter (P < 0.01), whereas gonadotrophin units were negatively associated with the number of follicles (P < 0.01). As expected, the women’s and their partners’ psychological variables were highly correlated (P < 0.01 for both anxiety and infertility-related stress).

Regression analysis

Regression analysis (Table 2) showed that the first model was significant (P < 0.01), and the three control variables were shown to be associated significantly with the number of follicles (P < 0.05, for duration of infertility and P < 0.01 for oestradiol and units of gonadotrophins). The second model showed the effects of the women’s infertility-related stress and state anxiety in predicting ovarian response. The results revealed that changing the model was not significant (P = 0.91) because a very low variance percentage (< 1%) was further explained by the introduction of women’s psychological factors. That is, women’s anxiety and infertility-related stress did not significantly affect prediction of the number of follicles (P = 0.68 and P = 0.76, respectively). The effect of the control variables remained unchanged when compared with the previous model.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regressions model.

| Model | R2 | R2 Change | F Change | p | Standardized coefficients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | P | ||||||

| I | 0.12 | 0.12 | 9.92 | 0.00 | ||||

| Duration | − 0.15 | − 2.29 | 0.02 | |||||

| Oestradiol peak value | 0.24 | 3.74 | 0.00 | |||||

| Units of gonadotropins (IU) | − 0.19 | − 2.91 | 0.00 | |||||

| II | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.91 | ||||

| Duration | − 0.15 | − 2.32 | 0.02 | |||||

| Oestradiol peak value | 0.24 | 3.66 | 0.00 | |||||

| Units of gonadotropins (IU) | − 0.19 | − 2.91 | 0.00 | |||||

| Women’s anxiety | − 0.03 | − 0.41 | 0.68 | |||||

| Women’s infertility-related stress | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.76 | |||||

| III | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.71 | 0.49 | ||||

| Duration | − 0.15 | − 2.27 | 0.02 | |||||

| Oestradiol peak value | 0.23 | 3.53 | 0.00 | |||||

| Units of gonadotropine (IU) | − 0.20 | − 2.96 | 0.00 | |||||

| Women’s anxiety | − 0.03 | − 0.45 | 0.65 | |||||

| Women’s infertility-related stress | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.51 | |||||

| Women × Men interaction anxiety | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.97 | |||||

| Women × Men interaction infertiltiy-related stress | − 0.08 | − 1.17 | 0.25 | |||||

The addition of the two interaction terms in the third model did not result in any significant change in the explained variance (< 1%, P = 0.49). The two interaction terms did not significantly predict ovarian response (P = 0.97 and P = 0.25, respectively for anxiety and infertility-related stress); the two main effects (women’s anxiety and infertility-related stress) remained non-significantly associated with the number of follicles. The effect of the control variables also remained unchanged when compared with the previous model.

Finally, the analyses were re-run by removing the unexplained infertility group from the dataset. The duration of infertility (b = -0.16; P < 0.05) and oestradiol peak value (b = 0.17; P < 0.05) both remained significant predictors of ovarian response in the first step. Women’s infertility-related stress (b = 0.01; P = 0.85) and anxiety (b = 0.01; P = 0.88) did not significantly predict ovarian response in the second step, nor the interaction between women’s and men’s infertility-related stress in the third step (b = -0.01; P = 0.92; b = -0.12; P = 0.16, for anxiety and stress respectively).

Discussion

This study tested different models examining: (i) the effect of women’s infertility-related stress and anxiety levels on the number of follicles ≥ 16 mm in diameter; and (ii) the potential intervening role of their partners’ psychological factors in this relationship. Contrary to our first hypothesis, no direct relationship was identified between a higher scores for women’s infertility-related stress and anxiety, and the number of follicles ≥ 16 mm in diameter.

The findings of this study are consistent with previous studies, which found no relationship between perceived stress and anxiety and ovarian response (Ebbesen et al., 2009, Nouri et al., 2011, Smeenk et al., 2001). As noted previously, numerous aspects of the study design increase confidence in the validity of the study findings. The association between a patient’s psychological variables and women’s biological response was tested using strict inclusion criteria (including women lacking an ascertained impairment of ovarian function), and an objective and precise outcome.

The current study included couples suffering from both male-factor and unexplained infertility. Some studies (Batstra et al., 2002, Wischmann, 2003) suggested that unexplained infertility may in itself be related to psychological variables or as yet unknown medical factors. However, the pattern of results from this study remained the same when the unexplained infertility sample was excluded from the analyses. Future studies should focus on psychological variables other than infertility stress and anxiety, by using strict outcome criteria.

The second aim of this study was to investigate the extent to which the male partner’s infertility stress and anxiety levels would serve as significant intervening variables in the relationship between a woman’s psychological factors and ovarian response. Contrary to our hypothesis, the males’ infertility-related stress did not impact on this relationship. A few studies have corroborated the influence of men’s psychological distress on women’s treatment outcome (Boivin and Schmidt, 2005, Quant et al., 2013), even though no firm conclusions could be drawn due to the elevated heterogeneity, among the samples, of the patient’s diagnosis. As far as is known, the present study is the first to examine the influence of a man’s distress on the relationship between his partner’s distress and her ovarian response in a sample with only male-factor infertility. However, a relationship between the male and female partner’s psychological distress was identified. This latter result is in line with previous studies exploring how each individual reaction to infertility may impact on the partner’s adjustment and infertility stress (Martins et al., 2014, Peterson et al., 2006, Peterson et al., 2011); only a few studies have explored how each partner’s reaction to infertility may impact on the other partner’s adjustment (Benyamini et al., 2009, Holter et al., 2006, Martins et al., 2014, Peterson et al., 2006, Peterson et al., 2008, Peterson et al., 2014).

This study has a number of limitations, which should be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, data were obtained from only one private Italian clinic; a broader, multi-centred study, including various clinical sites, might significantly verify the degree to which these results can be generalised. There being but a single assessment of couples’ infertility stress and anxiety at intake, further studies are required to investigate the association between patients’ psychological variables and ovarian performance at a subsequent point in time (e.g. prior to oocyte retrieval). Only FSH values and BMI were controlled in this study; other types of lifestyle behaviour were not taken into account (e.g. the effects of smoking) (Waylen et al., 2009) when exploring the associations between psychological variables and biological outcomes. Finally, only data on the follicles was reported as the assisted reproductive technology outcome. Further research is needed to explore more fully whether an individual’s psychological variables may impact on long-term adjustment to infertility for couples who remain childless. The long-term effects of a partner’s distress on an individual’s psychological adjustment following assisted reproductive technology treatment should also be further investigated.

Despite the above limitations, the authors of this research believe that this paper contributes to existing knowledge in the area of a couple’s infertility-related stress and its relationship with an assisted reproductive technology treatment outcome. Firstly, strict inclusion criteria were used in studying the ovarian response in order to exclude completely women’s biological contributions to infertility and, thereafter, it was supposed that only their psychological state could influence the outcome. Only assisted reproductive technology treatment with the same protocol was included in the study, in order to exclude any bias linked to the different protocols used, and key variables (i.e. cause of infertility, primary versus secondary infertility and initial assisted reproductive technology treatment) were controlled. Secondly, one objective and precise outcome (the mean number of follicles observed) was chosen as an outcome measure. The number of oocytes retrieved and the number of embryos transferred were not considered as outcomes because they may have been affected by too many biases (for example, embryo quality, oocyte retrieval or embryo transfer procedures). If there had been any association, the idea of modifying drug administration in function of the degree of psychological stress could have been more fully accounted for.

It is hoped that future research might take into account other psychological variables (relating to both partners), which might share various associations with ovarian response. Examples of the latter include: quality of life related to the infertility experience (via the FertiQoL tool), stable personality traits or dyadic adjustment in the couple’s relationship.

The authors of this study believe that it offers important clinical implications for both physicians and psychologists. Clinicians and psychologists will be able to reassure women that they will not compromise the outcome of ovarian stimulation because they or their partners are anxious or distressed. This encouragement may also help men to de-emphasize their psychological distress in couples suffering from male-factor infertility.

Moreover, the results of this study suggest that even though no relationship was found between pre-treatment psychological distress and response to ovarian stimulation, the levels of couples’ psychological distress were moderate to high, and strongly inter-correlated. It is widely known that the infertility experience affects both partners’ lives and the failure of this shared goal in life (i.e. becoming parents) affects the way each of them perceives himself/herself as a partner. Furthermore, the strong correlation between each partner’s scores of anxiety and infertility-related stress suggests that each partner’s distress may be affected not only by his/her own feelings regarding the infertility problem, but also by their partner’s feeling. Thus, the results of this study may support a clinician’s decision to actively involve both partners in the diagnosis and treatment process, in accordance with the ESHRE guidelines (Gameiro et al., 2015), in order to address the needs of both components in couples undergoing treatment as stressful as assisted reproductive technology.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funds provided by ANDROS Day Surgery Clinic, Reproductive Medicine Unit, Palermo, Italy.

Biography

Group analysis psychotherapist Dr. Zaira Donarelli has been a member of the clinical and scientific staff of the ANDROS Day Surgery Clinic in Palermo (Italy) since 2003. Her research and publications involved the psychological aspects of infertility, including couples’ dynamics, distress and quality of life. She is a reviewer for the following journals: Human Reproduction, Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, International Journal of Women's Health, International Journal of Fertility and Sterility, Reproductive BioMedicine Online and Sage Open.

Declaration: The authors report no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

References

- Angelini A., Brusco G., Barnocchi N., El-Danasouri I., Pacchiarotti A., Selman H. Impact of physician performing embryo transfer on pregnancy rates in an assisted reproductive program. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2006;23:329–332. doi: 10.1007/s10815-006-9032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batstra L., van de Wiel H.B.M., Schuiling G.A. Opinions about ‘unexplained subfertility’. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002;23:211–214. doi: 10.3109/01674820209074674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyamini Y., Gozlan M., Kokia E. Women’s and men’s perceptions of infertility and their associations with psychological adjustment: a dyadic approach. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009;14:1–16. doi: 10.1348/135910708X279288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Schmidt L. Infertility-related stress in men and women predicts treatment outcome 1 year later. Fertil. Steril. 2005;83:1745–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Bunting L., Collins J.A., Nygren K. An international estimate of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum. Reprod. 2007;22:1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Griffiths E., Venetis C.A. Emotional distress in infertile women and failure of assisted reproductive technologies: meta-analysis of prospective psychosocial studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans F., Verweij P., Eijkemans M., Mannaerts B., Witjes H. Prognostic models for high and low ovarian responses in controlled ovarian stimulation using a GnRH antagonist protocol. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29:1688–1697. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting L., Boivin J. Decision-making about seeking medical advice in an internet sample of women trying to get pregnant. Hum. Reprod. 2007;22:1662–1668. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B.C., Gerber J.R., McGettrick A.L., Johnson J.V. Perceived infertility-related stress correlates with in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil. Steril. 2007;88:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donarelli Z., Lo Coco G., Gullo S., Marino A., Volpes A., Allegra A. Are attachment dimensions associated with infertility-related stress in couples undergoing their first IVF treatment? A study on the individual and cross-partner effect. Hum. Reprod. 2012;27:3215–3225. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donarelli Z., Gullo S., Lo Coco G., Marino A., Scaglione P., Volpes A., Allegra A. Assessing infertility-related stress: the factor structure of the Fertility Problem Inventory in Italian couples undergoing infertility treatment. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015;36:58–65. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2015.1034268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen S.M.S., Zachariae R., Mehlsen M.Y., Thomsen D., Højgaard A., Ottosen L., Petersen T., Ingerslev H.J. Stressful life events are associated with a poor in-vitro fertilization (IVF) outcome: a prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 2009;24:2173–2182. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferin M. Clinical review 105: Stress and the reproductive cycle. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:1768–1773. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gameiro S., Boivin J., Dancet E., de Klerk C., Emery M., Lewis-Jones C., Thorn P., Van den Broeck U., Venetis C.A., Verhaak C.M., Wischmann T., Vermeulen N. ESHRE guideline: routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction–a guide for fertility staff. Hum. Reprod. 2015;30:2476–2485. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourounti K., Anagnostopoulos F., Vaslamatzis G. The relation of psychological stress to pregnancy outcome among women undergoing in-vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Women Health. 2011;51:321–339. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.574791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holter H., Anderheim L., Bergh C., Möller A. First IVF treatment-short-term impact on psychological well-being and the marital relationship. Hum. Reprod. 2006;21:3295–3302. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karande V., Morris R., Chapman C., Rinehart J., Gleicher N. Impact of the “physician factor” on pregnancy rates in a large assisted reproductive technology program: do too many coocks spoil the broth? Fertil. Steril. 1999;71:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff-Cohen H., Chu E., Natarajan L., Sieber W. A prospective study of stress among women undergoing in vitro fertilization or gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil. Steril. 2001;76:675–687. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasikova D.V., LeBreton J.M. Just Two of Us: Misalignment of Theory and Methods in Examining Dyadic Phenomena. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012;97:739–757. doi: 10.1037/a0027962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancastle D., Boivin J. Dispositional Optimism, Trait Anxiety, and Coping: unique or Shared Effects on Biological Response to Fertility Treatment? Health Psychol. 2005;24:171–178. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M.V., Peterson B.D., Almeida V., Mesquita-Guimarães J., Costa M.E. Dyadic dynamics of perceived social support in couples facing infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2014;29:83–89. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen S.M.S., Frederiksen Y., Ingerslev H.J., Zachariae R. Stress, distress and outcome of assisted reproductive technology (ART): a meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:2763–2776. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura-Ramos M., Gameiro S., Canavarro M.C., Soares I. Assessing infertility stress: re-examining the factor structure of the Fertility Problem Inventory. Hum. Reprod. 2012;27:496–505. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton C.R., Sherrard W., Glavac I. The Fertility Problem Inventory: measuring perceived infertility related stress. Fertil. Steril. 1999;72:54–62. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri K., Litschauner B., Huber J.C., Buerkle B., Tiringer D., Tempfer C.B. Saliva cortisol levels and subjective stress are not associated with number of oocytes after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2011;96:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrabissi L., Santinello M. Organizzazioni Speciali; Firenze, Italy: 1989. Nuova versione italiana dello S.T.A.I. – Forma Y. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B.D., Newton C.R., Rosen K.H., Schulman R.S. Coping Processes of Couples Experiencing Infertility. Fam. Relat. 2006;55:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B.D., Pirritano M., Christensen U., Schmidt L. The impact of partner coping in couples experiencing infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2008;23:1128–1137. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B.D., Pirritano M., Block J.M., Schmidt L. Marital benefit and coping strategies in men and women undergoing unsuccessful fertility treatments over a 5-year period. Fertil. Steril. 2011;95:1759–1763.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B.D., Sejbaek C.S., Pirritano M., Schmidt L. Are severe depressive symptoms associated with infertility-related distress in individuals and their partners? Hum. Reprod. 2014;29:76–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quant H.S., Zapantis A., Nihsen M., Bevilacqua K., Jindal S., Lubna P. Reproductive implications of psychological distress for couples undergoing IVF. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013;30:1451–1458. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenberg V., Seshadri S., Sunkara S.K., Sobaleva S., Oteng-Ntim E., El-Toukhy T. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2011;23:421–439. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Khabani A., Klein N., Battaglia D. Statistical analysis of factors affecting fertilization rates and clinical outcome associated with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil. Steril. 2003;79:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk J.M., Verhaak C.M., Eugster A., van Minnen A., Zielhuis G.A., Braat D.D. The effect of anxiety and depression on the outcome of in-vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod. 2001;16:1420–1423. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.7.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D., Gorsuch R.L., Lushene P.R., Vagg P.R., Jacobs G.A. C.A: Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto: 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) [Google Scholar]

- Waylen A.L., Metwally M., Jones G.L., Wilkinson A.J., Ledger W.L. Effects of cigarette smoking up on clinical outcomes of assisted reproduction: a metaanalysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2009;15:31–44. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischmann T.H. Psychogenic Infertility – Myths and Facts. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2003;20:485–494. doi: 10.1023/B:JARG.0000013648.74404.9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]