SUMMARY

The role of systemic inflammatory response as a prognostic factor has been proposed in a variety of cancers. The purpose of this study was to investigate the prognostic value of the pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in the incidence of pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) in patients who underwent total laryngectomy. We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of 141 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of larynx who underwent total laryngectomy from 2009 to 2015. The incidence of PCF was 49.6%. A higher risk of 23% was observed among patients with NLR > 2.5 for the occurrence of PCF (p = 0.007). Patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma who present elevated values in the ration > LR> (> 2.5) presented a higher risk of developing pharyngocutaneous fistula in the postoperative setting of total laryngectomy.

KEY WORDS: Laryngeal neoplasms, Squamous cell carcinoma, Postoperative complications, Cutaneous fistula

RIASSUNTO

Il ruolo della risposta infiammatoria sistemica come fattore prognostico è stato già proposto per molti tipi di tumore. Lo scopo di questo studio è stato quello di definire il valore prognostico del rapporto neutrofili-linfociti (NLR) pretrattamento come fattore di rischio per la fistola faringocutanea (PFC) in pazienti sottoposti a laringectomia totale. Abbiamo quindi analizzato retrospettivamente 141 pazienti con carcinoma squamoso della laringe trattati con laringectomia totale tra il 2009 e il 2015. L’incidenza d PCF è stata pari a 49,6%. In particolare, è stato osservato un rischio maggiore di sviluppare PFC, di circa il 23%, nei pazienti con NLR > 2,5 (p = 0,007). in conclusione, i pazienti con carcinoma squamoso della laringe con un elevato rapporto neutrofili-linfociti (> 2,5) presentano un maggiore rischio di sviluppare fistole faringocutanee nel post-operatorio della laringectomia totale.

PAROLE CHIAVE: Tumore laringeo, Carcinoma squamocellulare, Complicanze postoperatorie, Fistola cutanea

Introduction

Smoking and alcohol consumption are the most important risk factors for laryngeal cancer 1. Traditional prognostic factors, such as tumour staging, lymph node extracapsular spread and surgical margins have been commonly used to predict outcome for laryngeal cancer patients 2,3. However, those factors are often insufficient in determining prognosis, and the role of novel markers have been investigated.

It has been progressively recognised that oncological outcomes do not depend exclusively of tumour features, but also on the patient’s response, mainly regarding the immunologic condition 4. Some proinflammatory elements can strongly influence immunologic status by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting angiogenesis and DNA damage 5,6.

The role of inflammation in cancer pathogenesis has been extensively studied 5. The production of proinflammatory cytokines facilitates the proliferation and survival of tumour cells 7, whereas the increased release of these cytokines produces a systemic inflammatory response reflected in changes in circulating markers of inflammation, including white blood cells 8. Peripheral blood leukocyte count is a marker closely related to inflammation in patients. Increased leukocyte count can reflect an individual’s immune response to infection, inflammation and possibly cancer.

Counts of total white blood cells and its related components count can predict survival in a variety of malignancies, although a limited number of studies have evaluated the role of haematologic markers of inflammation as predictors of outcome in head and neck cancer patients. Recently, some studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and nasopharyngeal 9-11, oral 12-14 and laryngeal 15,16 cancer outcomes. Elevated NLR has been demonstrated to be associated with tumour progression and metastasis, with increased rates of mortality. Pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) is the most common surgical complication after total laryngectomy. It is due to a failure in the pharyngeal repair resulting in salivary leak and is associated with a higher incidence of morbidity, hospital stay and cost. Its incidence varies around 20-25%. In a recent meta-analysis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), previous haemoglobin < 12.5 g/dL, blood transfusion, previous radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, advanced primary tumour, supraglottic subsite, hypopharyngeal tumour site, positive surgical margins and the performance of neck dissection were risk factors for PCF 17. Elevated NLR was associated with tumour progression, although it has not been correlated to the rates of surgical complications.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the value of pretreatment NLR in predicting the incidence of PCF in patients who underwent total laryngectomy for larynx cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a retrospective and observational cohort study with evaluation of clinical charts among patients who underwent total laryngectomy for treatment of larynx squamous cell carcinoma at the Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo (ICESP), São Paulo, Brazil, from July 2009 to June 2015.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All consecutive patients with larynx squamous cell carcinoma and confirmed through histopathological analysis of the biopsy who underwent total laryngectomy were included. All surgical procedures had curative intent with radical resection of the tumour and without any evidence of distant metastasis or macroscopic residual lesion. Patients with comorbidities that could influence the serum levels of neutrophils, platelets and/or lymphocytes (infectious, inflammatory or autoimmune diseases) were excluded.

Data collected

A form was elaborated containing the following data collected from each chart: gender, age, tumour site (supraglottic, glottic, infraglottic or transglottic level), tumour extension (to hypopharynx), regional lymph node spread, histological differentiation (grades I, II or III), perineural and angiolymphatic invasion and preoperative serum values of neutrophils and lymphocytes at an interval of less than 1 month after surgery. The main outcome evaluated was the occurrence of PCF.

Statistical analysis

The NLR was calculated through the simple division of the absolute count of neutrophils by the absolute count of lymphocytes. The optimal cutoff value for defining a high NLR rate was established by an ROC curve (receiver operating characteristic). The cutoff value was the point closest to both maximum sensitivity and specificity for both measures. The measures of the main outcomes were expressed in absolute numbers and univariate analysis of the data was performed using a 2 x 2 table (risk difference) and compared using a chi-square test. Continuous variables were analysed considering the difference between the averages and standard deviations using a Student’s t test. A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 157 patients were eligible for the study. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 141 patients with larynx squamous cell carcinoma who underwent total laryngectomy were selected, including 117 men (83%) and an age varying from 41 to 83 years (mean 61.6 ± 9.1).

Five patients were excluded because they had been operated on another department with a lack of access to preoperative leucogram; 4 patients had a histological diagnosis different from squamous cell carcinoma; 4 patients due to the presence of macroscopic residual tumour after surgery; and 3 patients due to the presence of comorbidities that could change laboratory values.

Clinical and demographic data and the NLR values are shown in Tables I and II, respectively. In general, patients with more advanced clinical staging and worse pathological findings, representing poorer prognosis, presented higher NLR values. The overall incidence of PCF was 49.6%. Gender, age, tumour extension and neck metastasis did not influence the incidence of PCF (Table III). Patients who underwent salvage laryngectomy presented a higher risk for PCF of about 25% (70.8% x 45.3%, p = 0.02). Primary closure, flaps (supraclavicular, pectoralis major or microsurgical free flaps) and linear stapler were employed for pharyngeal closure in 52.5%, 17.7% and 29.8% of cases, respectively. Compared to primary closure, the linear stapler reduced the risk for PCF by 22% (p = 0.02), whereas there was no difference when free flaps were employed (p = 0.39).

Table. I.

Clinical and demographic data.

| Data | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 117 (82.9%) |

| Women | 24 (17.0%) |

| Age | |

| ≤ 60 | 73 (51.8%) |

| > 60 | 68 (48.2%) |

| Tumour site | |

| Glottic | 14 (9.9%) |

| Supraglottic | 9 (6.4%) |

| Glottic + supraglottic | 11 (7.8%) |

| Glottic + Subglottic | 7 (4.9%) |

| Supraglottic + hypopharynx | 13 (9.2%) |

| Transglottic | 53 (37.6%) |

| Transglottic + hypopharynx | 28 (19.9%) |

| Hypopharynx | 6 (4.3%) |

| T stage | |

| T2 | 10 (7.1%) |

| T3 | 36 (25.5%) |

| T4 | 95 (67.4%) |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 72 (51.1%) |

| N1 | 17 (12.1%) |

| N2 | 48 (34.0%) |

| N3 | 4 (2.8%) |

| Histological differentiation grade | |

| I | 24 (17.2%) |

| II | 96 (68.1%) |

| III | 21 (14.7%) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Present | 60 (42.7%) |

| Absent | 81 (57.3%) |

| Angiolymphatic invasion | |

| Present | 47 (33.3) |

| Absent | 94 (66.7%) |

Table. II.

Correlation between inflammatory markers and pathological findings.

| Data | n | Neutrophils | p | Lymphocytes | p | NLR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T stage | |||||||

| T2-T3 | 46 | 5043 ± 2466 | 0.11 | 1941 ± 687 | 0.4 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 95 | 6130 ± 3047 | 1802 ± 769 | 4.3 ± 3.6 | |||

| N stage | |||||||

| N- | 72 | 5583 ± 3104 | 0.25 | 1811 ± 608 | 0.01 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| N+ | 69 | 5985 ± 2702 | 1968 ± 820 | 3.8 ± 2.9 | |||

| N stage | |||||||

| N1 | 17 | 5696 ± 2861 | 0.68 | 2140 ± 735 | 0.55 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 0.03 |

| N2-N3 | 52 | 6079 ± 2670 | 1911 ± 845 | 4.0 ± 3.1 | |||

| Histological differentiation grade | |||||||

| I | 24 | 5446 ± 1859 | 0.23 | 2102 ± 511 | 0.26 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| II / III | 117 | 5544 ± 2304 | 1831 ± 626 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | |||

| Perineural invasion | |||||||

| Present | 60 | 5255 ± 1833 | 0.01 | 1871 ± 697 | 0.04 | 3.6 ± 2.6 | < 0.001 |

| Absent | 81 | 5739 ± 2476 | 1882 ± 547 | 3.3 ± 1.5 | |||

| Angiolymphatic invasion | |||||||

| Present | 47 | 5240 ± 1526 | < 0.001 | 1724 ± 603 | 0.96 | 3.9 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Absent | 94 | 5675 ± 2504 | 1956 ± 609 | 3.2 ± 1,5 | |||

Table. III.

Risk factors associated with PCF.

| Variables | Without PCF (n = 71) | With PCF (n = 70) | Difference of absolute risk (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 62 | 55 | 15.5% (-5.88 to 36.87%) | 0.18 |

| Women | 9 | 15 | ||

| Age | ||||

| < 60 | 31 | 32 | 2.1% (-14.52 to 18.67%) | 0.81 |

| ≥ 60 | 40 | 38 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| T2-T3 | 26 | 20 | 9.2% (-8.34 to 26.65%) | 0.31 |

| T4 | 45 | 50 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| N- | 41 | 31 | 13.5% (-2.89 to 29.82%) | 0.11 |

| N+ | 30 | 39 | ||

| Spread to hypopharynx | ||||

| Yes | 29 | 30 | 2.1% (-14.66 to 18.79%) | 0.81 |

| No | 42 | 40 | ||

| Pharynx closure | ||||

| Primary | 31 | 43 | - | - |

| Stapler | 27 | 15 | 22.4% (4.06 to 40.73%)a | 0.02a |

| Flap | 13 | 12 | 10.1% (-12.47 to 32.69%)b | 0.39b |

| Previous radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 17 | 25.5% (5.24 to 45.83%) | 0.02 |

| No | 64 | 53 | ||

| NLR | ||||

| ≤ 2.5 | 36 | 20 | 23.1% (6.77 to 39.45%) | 0.007 |

| > 2.5 | 35 | 50 | ||

a Primary x stapler

b Primary x flap.

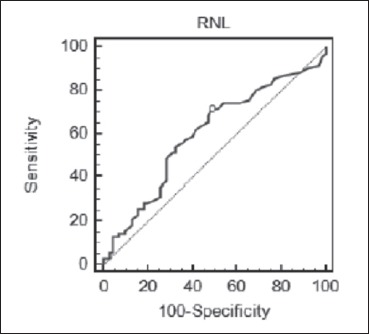

A value of 2.5 [sensitivity = 71.4%, specificity = 51.4%, area under the curve (AUC) = 0.600; Fig. 1] was established as a cutoff value for defining the NLR before surgery. Thus, patients with NLR > 2.5 presented a higher absolute risk of 23% for the occurrence of PCF compared to those with NLR ≤ 2.5 (p = 0.007). Among patients who presented PCF in the postoperative period, 48 (68.6%) had resolution in the first month under conservative measures, whereas in 11 patients (15.1%) the fistula was permanent and in 9 patients (12.8%) a surgical approach was necessary to correct the dehiscence. The mean NLR among patients who presented conservative resolution of the PCF during the first postoperative month was 3.0 ± 1.4 compared to 4.2 ± 3.3 of those who had resolution after the first month and those who continued with the PCF (p < 0.001). The variables that presented significant difference in the incidence of PCF at univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model (Table IV). NLR > 2.5 was the only risk factor associated with the incidence of PCF (OR = 2.44; 95% CI 1.18 to 5.03; p = 0.01).

Fig. 1.

ROC curve related to NLR and PCF incidence.

Table. IV.

Multivariate analysis of the risk factor for PCF.

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard error | OR | 95% CI | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous radiotherapy | 0.5186 | 0.4938 | 1.68 | 0.64 to 4.42 | 0.29 |

| RNL ≥ 2.5 | 0.8901 | 0.3700 | 2.44 | 1.18 to 5.03 | 0.01 |

OR = Odds ratio

* = logistic regression.

Discussion

The cytokine network of several tumours is rich in inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and chemokines. Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which can be produced by te tumour cells and/or tumour-associated leucocytes and platelets, may contribute directly to malignant progression. Many cytokines and chemokines are inducible by hypoxia, which is a major physiological difference between tumour and normal tissue 5. Chronic inflammation associated with infection or autoimmune disease precedes tumour development and can contribute to it through induction of oncogenic mutations, genomic instability, early tumour promotion and enhanced angiogenesis. This inflammatory response can enhance neoangiogenesis, promote tumour progression and metastatic spread, cause local immunosuppression and further augment genomic instability. Cancer-related inflammation causes suppression of antitumour immunity by recruiting regulatory T cells and activating chemokines, which results in tumour growth and metastasis. The presence of both neutrophilia and thrombocytosis tends to represent a nonspecific response to cancer-related inflammation. Cancer has been shown to produce myeloid growth factors, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6, which may influence tumour-related leukocytosis and neutrophilia 18. Cancer therapy can also trigger an inflammatory response by causing trauma, necrosis and tissue injury that stimulate tumour re-emergence and resistance to therapy. However, in some cases, therapy-induced inflammation can enhance antigen presentation, leading to immune-mediated tumour eradication 19. Chronic inflammation caused by infection, autoimmune disease and exposure to irritants as well as tumour-associated inflammation contribute to tumour promotion, progression and metastatic spread. Whereas in inflammation-associated cancer inflammation can be viewed as a causative agent affecting either tumour initiation or early promotion, tumour-elicited inflammation acts as a late tumour promoter to enhance progression and metastasis 20.

The NLR is a nonspecific marker of systemic inflammation. An elevated preoperative NLR (≥ 5) may correlate with an increased risk of recurrence and death in patients who undergo hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases and for primary hepatocellular carcinoma 21,22. Clinically, peripheral blood leukocyte count is a marker closely related to inflammation in patients. Increased leukocyte count usually reflects an individual’s immune response to infection and inflammation, and perhaps malignancies. Elevation of NLR in cancer patients indicates a decrease of antitumour activity, implying that tumour development may be related to NLR imbalance in cancer patients. Elevated NLR has been demonstrated to be associated with tumour progression and metastasis 6.

A total of 295 patients underwent oesophagectomy with 56 patients (18.9%) presenting elevated NLR preoperatively. In multivariable analysis, elevated NLR was associated with significantly poorer disease-free (hazard ratio [HR] 2.26, 95% CI 1.43-3.55) and overall survival (HR = 2.31, 95% CI 1.53-3.50). Thus, an elevated preoperative NLR was associated with a nearly 2-fold increased risk of recurrence and death, independent of other patient and tumour characteristics associated with poor outcomes. NLR reflected systemic inflammation and may serve as a composite “score” that reflects the degree of host inflammatory cell activity that promotes tumour growth and progression 23. In a series of 483 patients who underwent oesophagectomy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, high preoperative NLR (≥ 3.5 vs. < 3.5, p = 0.039) and platelet lymphocyte ratio PLR (≥ 150 vs < 150, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with poorer overall survival in multivariate analysis. In a group of patients diagnosed with locally advanced oesophageal cancer, compared with the low (< 2.0) NLR group (n = 43, 31.2%), the high (≥ 2.0) NLR group (n = 95, 68.8%) exhibited significant decreases in both progression-free and overall survival. Multivariate analysis showed similar findings 24.

One of the reasons for the differences observed in the association of NLR with survival may be due to the different methods that have been used to identify and categorise NLR cutoff values. The to methods most commonly used are receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and comparison of medians and quartiles 16.

Pretreatment NLR and percentages of lymphocyte and neutrophil were found to be independent prognostic factors and clinically useful biomarkers for survival in 1410 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma 10. Eight independent prognostic factors were identified in 3237 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma who underwent radiation therapy, including anaemia or thrombocytosis during radiotherapy, continuous reduction in haemoglobin and high NLR before radiotherapy 11.

In a retrospective study of 226 patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma, preoperative C-reactive protein CRP level ≥ 5.0 mg/L was significantly associated with NLR ≥ 2.44 (linear regression, p < 0.001). Elevated CRP and NLR were significantly associated with pathological tumour status (p < 0.001), pathologic nodal metastasis (p < 0.001), tumour depth (≥ 10 mm vs < 10 mm, p < 0.001), disease-free survival (p < 0.001) and overall survival (p < 0.001). CRP was considered an independent prognostic factor, and incorporating NLR into CRP level had significant potential as a biomarker for risk stratification of oral cancer 14. A cohort of 97 patients with locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma receiving preoperative chemoradiotherapy was retrospectively evaluated. In multivariate analysis, advanced pathologic TNM stage after neoadjuvant therapy, positive perineural invasion and high pretreatment NLR (HR = 10.37, p = 0.029) were independent factors associated with poor disease-specific survival 13. In a group of 273 retrospectively evaluated patients with head and neck cancer, higher pretreatment NLR (> 4.27) was associated with higher rates of recurrence (35% compared to 7%; p < .0001).

In addition to inflammatory cells, tumour stroma consists of new blood vessels, connective tissue and a fibrin-gel matrix. Wound healing is usually self-limiting whereas tumours secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which can lead to persistent extravasation of fibrin and fibronectin and continuous generation of extracellular matrix. Platelets in wounds are a critical source of cytokines and VEGF. Platelet release of such factors may also be important in tumour angiogenesis 25. In addition, malignant cells also secrete proinflammatory cytokines 5.

Tumours interact both directly and indirectly with host inflammatory cells. The NLR is a nonspecific marker of systemic inflammation. Regarding laryngeal tumours, the optimal cutoff values of the NLR have been reported to be 2.17 26 and 2.46 27. We found that a cutoff value of 2.5 for a higher risk of PCF as a complication. The NLR is a simple and effective marker of the patient’s inflammatory and immunity status. Patients with elevated NLR usually have relative lymphocytopenia, and this may reflect a deficient immune response to tumours 26. This is also a possible factor for increasing PCF rates.

Conclusions

Patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma who present elevated values in the NLR (> 2.5) have a higher risk of developing pharyngocutaneous fistula in the postoperative period following total laryngectomy.

References

- 1. Périé S, Meyers M, Mazzaschi O, et al. Épidémiologie et anatomie des cancers ORL. Bull Cancer 2014;101:404-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Testa D, Galli V, de Rosa G, et al. Clinical and prognostic aspects of laryngeal clear cell carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol 2005;119:991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cojocariu OM, Huguet F, Lefevre M, et al. [Prognosis and predictive factors in head-and-neck cancers]. Facteurs pronostiques et prédictifs des cancers des voies aérodigestives supérieures. Bull Cancer 2009;96:369-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. MacDonald N. Cancer cachexia and targeting chronic inflammation: a unified approach to cancer treatment and palliative/supportive care. J Support Oncol 2007:5;157-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001;357:539-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002;420:860-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 2009;30:1073-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kao SC, Pavlakis N, Harvie R, et al. High blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an indicator of poor prognosis in malignant mesothelioma patients undergoing systemic therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:5805-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. An X, Ding PR, Wang FH, et al. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2011;32:317-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He JR, Shen GP, Ren ZF, et al. Pretreatment levels of peripheral neutrophils and lymphocytes as independente prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 2012;34:1769-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang H, Gao J, Xu BQ, et al. Haemoglobin, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet count improve prognosis prediction of the TNM staging system in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: development and validation in 3237 patients form a single institution. Clin Oncol 2013;25:638-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khandavilli SD, Ceallaigh PO, Lloyd CJ, et al. Serum C-reactive protein as a prognostic indicator in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2009;45:912-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perisanidis C, Kornek G, Pöschl PW, et al. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independente marker of poor disease-specific survival in patients with oral cancer. Med Oncol 2013;30:334-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fang HY, Huang XY, Chien HT, et al. Refining the role of preoperative C-reactive protein by neutrophil/lymphocyte ration in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2013;123:2690-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tu XP, Qiu QH, Chen LS, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic marker in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2015;15:743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wong BYW, Stafford ND, Green VL, et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2016;38:E1903-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dedivitis RA, Aires FT, Cernea CR, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistula after total laryngectomy: a systematic review of risk factors. Head Neck 2015;37:1691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhatti I, Peacock O, Lloyd G, et al. Preoperative hematologic markers as independent predictors of prognosis in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet lymphocyte ratio. Am J Surg 2010;200:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010;140:883-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Inflammation and oncogenesis: a vicious connection. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2010;20:65-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Halazun KJ, Aldoori A, Malik HZ, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival following hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malik HZ, Gomez D, Wong V, et al. Predictors of early disease recurrence following hepatic resection for colorectal cancer metastasis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2007;33:1003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharaiha RZ, Halazun KJ, Mirza F, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of postoperative disease recurrence in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3362-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feng JF, Huang Y, Chen QX. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is superior to neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predictive factor in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pinedo HM, Verheul HMW, D’Amato RJ, et al. Involvement of platelets in tumour angiogenesis? Lancet 1998;352:1775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tu XP, Qiu QH, Chen LS, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic marker in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2015;15:743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong BYW, Stafford ND, Green VL, et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2016;38:E1903-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]