Summary

Background

Patients with cirrhosis are at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The SEPT9 gene is a key regulator of cell division and tumor suppressor whose hypermethylation is associated with liver carcinogenesis. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of a PCR-based assay for the analysis of SEPT9 promoter methylation in circulating cell-free DNA (mSEPT9) for diagnosing HCC among cirrhotic patients.

Methods

We report two phase II biomarker studies that included cirrhotic patients with or without HCC from France (initial study) and Germany (replication study). All patients received clinical and biological evaluations, and liver imaging according to current recommendations. The primary outcome was defined as the presence of HCC according to guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed by abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan and systematically discussed in a multidisciplinary consultation meeting. HCC-free cirrhotic patients were recruited if the screening abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of HCC at the time of blood sampling for the mSEPT9 test and on the next visit six months later. The adjudicating physicians were blinded to patient results associated with the mSEPT9 test.

Findings

We included 289 patients with cirrhosis (initial: 186; replication: 103), among whom 98 had HCC (initial: 51; replication: 47). The mSEPT9 test exhibited high diagnostic accuracy for HCC diagnosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.944 (0.900–0.970, p < 0.0001) in the initial study (replication: 0.930 [0.862–0.971, p < 0.0001]; meta-analysis: AUROC = 0.940 [0.910–0.970, p < 0.0001], no heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, p = 0.67; and no publication bias). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, the number of positive mSEPT9 triplicates was the only independent variable significantly associated with HCC diagnosis (initial: OR = 6.30, for each mSEPT9 positive triplicate [2.92–13.61, p < 0.0001]; replication: OR = 6.07 [3.25–11.35, p < 0.0001]; meta-analysis: OR = 6.15 [2.93–9.38, p < 0.0001], no heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, p = 0.95; no publication bias). AUROC associated with the discrimination of the logistic regression models in initial and validation studies were 0.969 (0.930–0.989) and 0.942 (0.878–0.978), respectively, with a pooled AUROC of 0.962 ([0.937–0.987, p < 0.0001], no heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, p = 0.36; and no publication bias).

Interpretation

Among patients with cirrhosis, the mSEPT9 test constitutes a promising circulating epigenetic biomarker for HCC diagnosis at the individual patient level. Future prospective studies should assess the mSEPT9 test in the screening algorithm for cirrhotic patients to improve risk prediction and personalized therapeutic management of HCC.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Circulating cell-free DNA-based epigenetic biomarker, DNA methylation, mSEPT9

Highlights

-

•

Patients with cirrhosis are at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

-

•

Accurate tumor biomarkers for the diagnosis and early detection of HCC need to be developed.

-

•

The circulating, cell-free, epigenetic biomarker mSEPT9 is a promising biomarker for diagnosing HCC in patients with cirrhosis.

Patients with cirrhosis are at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Several circulating epigenetic markers are under evaluation in HCC, notably those identified through “omics” approaches. However, to date, no circulating epigenetic biomarker has been shown to be useful for HCC diagnosis at the individual patient level. Through initial and replication phase II biomarker studies, we showed that the circulating, cell-free, DNA-based epigenetic biomarker mSEPT9 is a promising biomarker for diagnosing HCC in patients with cirrhosis. Future prospective studies should assess the mSEPT9 test in a screening algorithm for patients with cirrhosis to improve risk prediction and the personalized therapeutic management of HCC.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary malignant tumor of the liver (El-Serag, 2011; Bruix et al., 2016; Oussalah et al., 2016). It is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women, and ranks second in annual cancer mortality rates worldwide, with liver cancer diagnosed in >700,000 people annually (El-Serag, 2011; Bruix et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2017). Major risk factors for HCC include cirrhosis, infection with hepatitis B (HBV) or C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The 5-year cumulative risk for HCC development in patients with cirrhosis ranges between 5 and 30%, depending on the cause, with the highest risk among those infected with HCV (El-Serag, 2011).

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) has been widely used as a diagnostic marker for HCC. However, according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines, AFP is insufficiently sensitive or specific for use in a screening assay (Bruix & Sherman, 2011). Moreover, according to the European Association For The Study Of The Liver-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EASL-EORTC) clinical practice guidelines on HCC management, AFP is suboptimal for routine clinical practice (J. Hepatol., 2012). Furthermore, AFP has a lower diagnostic accuracy for detecting HCC in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis (Gopal et al., 2014).

Epigenetic alterations are a common hallmark of human cancer (Moran et al., 2017; Hao et al., 2017). Several lines of evidence suggest that the septin 9 gene (SEPT9) is a key regulator of cell division and a tumor suppressor whose hypermethylation is associated with liver carcinogenesis (Scott et al., 2005; Kakehashi et al., 2011; Villanueva et al., 2015). SEPT9 expression is ubiquitous in healthy tissues but is decreased or silenced by aberrant promoter hypermethylation in liver cancer (Uhlen et al., 2015; Wasserkort et al., 2013). An epigenome-wide association study of 304 HCC tissue samples showed that SEPT9 is a significant epi-driver gene in liver carcinogenesis, via SEPT9-promoter hypermethylation (Villanueva et al., 2015).

Aberrantly methylated DNA sequences originating from tumors are detectable in the circulation of patients with cancer using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Esteller et al., 1999; Wong et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2017). Several circulating epigenetic markers are under evaluation in HCC, notably those identified using “omics” approaches (Xu et al., 2017). Nevertheless, to date, no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved circulating epigenetic biomarker has been shown to be useful to diagnose HCC at the individual patient level. Given the high incident risk of HCC in patients with cirrhosis, we conducted initial and replication studies to investigate whether measurement of SEPT9 promoter methylation in circulating cell-free DNA (mSEPT9 test) would be useful to diagnose HCC among patients with cirrhosis.

1.1. Specific Objectives

The primary aim was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test to diagnose HCC among patients with cirrhosis. The secondary aims were: 1) to identify variables that are independently associated with HCC diagnosis to account for potential confounders for the diagnostic performance of the mSEPT9 test; 2) to evaluate the accuracy of the mSEPT9 test to diagnose Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage A HCC; 3) to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test among patients with HCV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis; 4) to compare the diagnostic performance of the mSEPT9 test with that of AFP; and 5) to calculate the categorical net reclassification improvement (NRI) of a mSEPT9-based strategy to diagnose HCC compared with an AFP-based strategy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

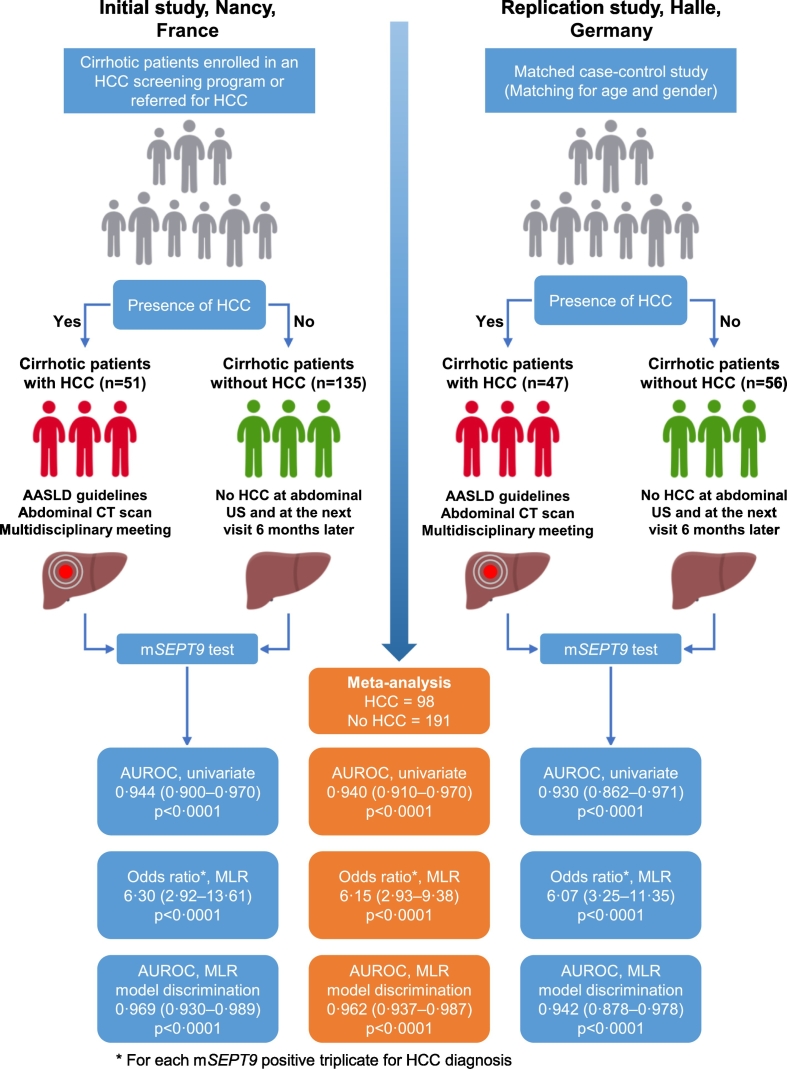

We report two phase II biomarker studies that included patients with cirrhosis with or without HCC from France (initial study: the SEPT9 study) and Germany (replication study) (Fig. 1). According to Sackett's classification, phase II biomarker studies aim to assess the magnitude of the association between the results of a biomarker and the disease status (Sackett & Haynes, 2002). Phase II biomarker studies are concerned with reproducibility and aim to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the biomarker, together with its ability to “rule out” (high sensitivity) or “rule in” (high specificity) the disease (Sackett & Haynes, 2002; Akiyama et al., 2014).

Fig. 1.

Study design and diagnostic accuracy measures obtained in the initial (Nancy, France) and replication (Halle, Germany) studies, and their meta-analysis for the assessment of the mSEPT9 test to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma. AASLD: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; AUROC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CT: computed tomography; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; MLR: multivariate logistic regression model; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; US: ultrasonography.

2.2. Initial Study: The SEPT9 Study (Nancy, France)

The SEPT9 study was a standardized observational study that recruited patients with cirrhosis with or without HCC with a high degree of ascertainment, including a multidisciplinary consultation meeting (gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons) on a weekly basis at the University Hospital of Nancy. Patients were recruited between June 2012 and April 2014. The HCC study population included: 1) patients with cirrhosis enrolled in an HCC screening program and for whom a diagnosis of HCC was made and ascertained by an abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, and 2) patients with cirrhosis who were directly referred for HCC. HCC-free patients with cirrhosis were recruited if the screening abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of HCC at the time of blood sampling for the mSEPT9 test and on the next visit six months later. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had missing clinical and/or radiological data. All patients received clinical and biological evaluations and liver imaging, according to international recommendations (Bruix & Sherman, 2011). Biochemical data were collected in an electronic database and extracted for this study using the general laboratory information management system (v8.11.6; MIPS France S.a.r.l., Paris, France). Clinical data were retrieved through electronic chart review using DxCare software (MEDASYS, Clamart, France). All patients with a diagnosis of HCC were discussed in the weekly multidisciplinary gastrointestinal oncology meeting dedicated to HCC (gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons). The clinical data and treatment decisions related to HCC were recorded in the e-RCP SOLSTIS platform (https://www.sante-lorraine.fr/), which is the official secured online service for managing and producing multidisciplinary consultation meeting reports for patients with a diagnosis of cancer. The following data were available in the electronic database: 1) demographic data, including age and gender; 2) clinical data, including the etiology of cirrhosis (alcohol, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH], HCV, HBV, autoimmunity, or hemochromatosis), and Child-Pugh score; 3) for patients with a diagnosis of HCC: the number of HCC nodules, the size of the largest HCC nodule, and the BCLC stage; and 4) blood biomarkers, including albumin, total bilirubin, and prothrombin activity (percentage). All patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Nancy approved the study. The Nancy Biochemical Database was reported to the French National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties (CNIL No. 1763197v0), which supervises the protection of individuals during the processing of personal data (Oussalah et al., 2015).

2.3. Replication Study: Halle, Germany

The replication study was a matched case-control study. Patients with cirrhosis and HCC represented the cases and were recruited between February 2013 and June 2016 at the Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Halle (Germany). HCC-free patients with cirrhosis were recruited at the same facility and were matched by age and gender. All patients with a diagnosis of HCC were discussed in multidisciplinary consultation meeting (gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons). HCC-free patients with cirrhosis were recruited if the screening abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of HCC at the time of blood sampling for the mSEPT9 test and on the next visit six months later. The following data were available through medical chart review: 1) demographic data, including age and gender; 2) clinical data, including the etiology of cirrhosis and Child-Pugh score; and 3) for patients with a diagnosis of HCC: the number of HCC nodules, the size of the largest HCC nodule, and BCLC stage. All patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Halle approved the study.

2.4. Diagnosis of HCC

All patients received clinical and biological evaluation, and liver imaging according to the AASLD guidelines (Bruix & Sherman, 2011). A diagnosis of HCC was confirmed using an abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan and systematically discussed in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. The adjudicating physicians (VL, initial study; AZ, replication study) were blinded to patients' results associated with the mSEPT9 test.

2.5. Plasma mSEPT9 Test

We collected blood samples by phlebotomy using lavender-topped EDTA Vacutainer Tubes 10 mL (BD Medical Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and prepared plasma (3.5 mL) from blood samples within 4 h of collection by centrifugation of blood tubes (1350 ± 150 rcf, 12 min), transfer to a 15-mL polypropylene centrifuge tube with a conical bottom, and recentrifugation (1350 ± 150 rcf, 12 min) as recommended by the manufacturer's protocol (http://www.epiprocolon.com/; REF M5–02-001, M5–02-002, and M5–02-003). Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis at the Department of Molecular Medicine and Personalized Therapeutics, Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, University Hospital of Nancy, in the initial study; and the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the University Hospital of Halle in the replication study. We used an Epi proColon 2.0 CE (Epigenomics AG, Berlin, Germany) qualitative test for real-time PCR detection of mSEPT9 DNA in bisulfite-converted DNA from human plasma samples according to the manufacturer's protocol. According to the FDA statement, the mSEPT9 test is a qualitative in vitro diagnostic test to detect methylated SEPT9 DNA in EDTA plasma derived from patient whole blood specimens (Epigenomics, 2016). It uses a real-time PCR with a fluorescent hydrolysis probe for the methylation specific detection of the SEPT9 DNA target (Epigenomics, 2016). The mSEPT9 assay consists of DNA extraction from plasma, bisulfite conversion of DNA, purification of bis-DNA, and real-time PCR. Real-time PCR analysis was performed on a LightCycler 480 instrument I (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland) in the initial study and an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (ABI7500; Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) in the replication study. PCR was performed in triplicate, and PCR curves for mSEPT9 were generated. According to manufacturer protocol, the validity of each sample batch was determined by SEPT9 and ACTB crossing point (CP) values for the positive and negative controls, using the following thresholds: positive control (CP_SEPT9 ≤40.6 and CP_ACTB ≤29.5, for the three PCR); negative control (no CP for SEPT9 and CP_ACTB ≤36.5, for the three PCR). Patient triplicate was considered as valid if the CP_ACTB was ≤33.1. The triplicate was considered as “SEPT9 positive” if the CP_SEPT9 was <50, and it was considered as “SEPT9 negative” if no CP_SEPT9 was reported. The median CP_SEPT9 value from both initial and replication studies was 36 (IQR, 33–39). The mSEPT9 test is designed by the manufacturer to return four possible results in increasing order of the number of positive triplicates (0/3, 1/3, 2/3, or 3/3). Importantly, these results do not correspond to the repeatability of the experiment. According to this principle, the results of the mSEPT9 test correspond to a continuous, ordinal variable that can vary between 0 and 3.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Quantitative variables are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR, 25th and 75th percentiles). Categorical variables are summarised as frequency counts and percentages. We assessed the diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test and AFP using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (DeLong et al., 1988). The classification variable used in the ROC analysis was the diagnosis of HCC. For each ROC analysis, we reported the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and the associated p-value. The exact binomial method was applied to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the AUROC. The optimal diagnostic cut-off was defined using the Youden index J. Bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa)-bootstrap interval after 10,000 iterations for the Youden index and its associated values were performed (Efron & Tibshirani, 1994). Other diagnostic accuracy measures included: sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and positive and negative predictive values. Pairwise AUROC comparison was carried out according to the procedure described by Delong et al. (DeLong et al., 1988) To derive variables that are potentially associated with HCC in univariate analysis, we performed univariate binary logistic regression using HCC diagnosis as a dependent variable. To identify variables that are independently associated with a diagnosis of HCC, all significant items resulting from the univariate analyses were integrated into a binary logistic regression model for multivariate analysis using HCC diagnosis as a dependent variable. All variables with p < 0.1 were included in the model and variables with p < 0.05 were retained in the model. The Child-Pugh score was used as a covariate instead of albumin, bilirubin, and prothrombin time, because these three variables are used to calculate the Child-Pugh score, thus avoiding collinearity issues. The results are shown as the regression coefficient, standard error (SE), odds ratios (ORs), and 95% CI for each independent predictor, and the percentage of cases correctly classified by the logistic regression model. We assessed model discrimination using ROC analysis and model calibration using the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. To estimate the pooled effect size for diagnostic accuracy measures retrieved from the initial and replication studies, we performed meta-analyses on the sensitivities, specificities, negative predictive values (NPVs), positive predictive values (PPVs), and ORs using the generic inverse variance method (Borenstein et al., 2009) under the random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird procedure) (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986). Pooled AUROC was calculated using the weighted summary AUROC method under the random-effects model (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986) as described by Zhou et al. (2009) We assessed statistical significance for heterogeneity by use of the χ2-based Q statistic and the I2 statistic for the extent of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was considered significant if p < 0.1 and I2 > 50% (Higgins et al., 2003). Considering pooled sensitivities and specificities for each threshold of the mSEPT9 test result, we used a Bayesian approach to assess the PPV and the NPV and their 95% CI according to an HCC prevalence ranging from 1 to 99%, as described by Mercaldo et al. (Mercaldo et al., 2007) We assessed the categorical NRI of the mSEPT9-based strategy (≥2 positive triplicates) in comparison with the AFP-based strategy (AFP >20 ng/mL, optimal threshold according to EASL-EORTC guidelines (2012)) for the diagnosis of HCC as a classification variable. The categorical NRI is an index that attempts to quantify how well the mSEPT9-based model reclassifies patients compared with the AFP-based model (Leening et al., 2014). The categorical NRI is reported as a percentage with 95% CI and the associated p-value (Kundu et al., 2011; Team RC, 2013). All statistical analyses, except NRI analysis, were conducted using the SAS® 9.4 platform (Cary, NC, USA), MedCalc for Windows v16.8.4 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 2.2.050; BioStat Software, Englewood, NJ, USA) on the basis of a two-sided type I error with an alpha level of 0.05. The NRI analysis was performed using the PredictABEL R package (http://www.genabel.org/packages/PredictABEL) (Kundu et al., 2011; Team RC, 2013). All statistical analyses related to secondary aims #1 and #2 were based on both the initial and replication studies. The statistical analyses related to secondary aims #3 to #5 were based on the initial study.

2.7. Study Power and Sample-size Calculation

We calculated the number of subjects required in the initial study on the basis of the primary aim. Using an alpha risk of 0.05, a study power of 95%, an expected AUROC of 0.95 that was compared with a reference AUROC of 0.75 (two-sided test), a ratio of cases:controls of 1:3, and a hypothesised rank correlation coefficient of 0.5 in both cases and controls, the required number of patients with HCC was 29, and the required number of patients without HCC was 87, for a total of 116 patients. In the replication study, using a study power of 80% instead of the highly stringent threshold of 95% used in the initial study, and a ratio of cases:controls of 1:1, the number of patients in each group was 30, for a total of 60 patients. Both the initial and replication studies were well powered for the primary outcome.

2.8. Role of the Funding Source

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

3. Results

In the initial study, a total of 191 patients were included. Among these, five had insufficient clinical and/or radiological data, leaving 186 patients for the final analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among the 186 cirrhotic patients retained in the final analysis, 51 had HCC (Table 1; Fig. 1). In the replication study, a total of 143 patients were included. Among these, 34 cirrhotic patients had insufficient clinical and/or radiological data, and six HCC patients had been previously treated with selective internal radiation therapy, leaving 103 patients for the final analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Among the 103 cirrhotic patients retained in the final analysis, 47 had HCC (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and biological variables associated with HCC diagnosis in univariate analysis.

| Initial study: Nancy (France) | Patients without HCC (n = 135) | Patients with HCC (n = 51) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | OR (95% CI) | pa |

| Age (years) | 57 (49–66) | 69 (61–75) | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | <0.0001 |

| Child-Pugh score at inclusion | 5 (5–5) | 6 (5–7) | 3.03 (1.91–4.81) | <0.0001 |

| mSEPT9, number of positive triplicates (0 to 3) | 0 (0–1) | 3 (3–3) | 9.06 (4.85–16.96) | <0.0001 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 4.6 (2.8–8.0) | 18.1 (7.1–265.1) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.004 |

| Number of HCC nodules (n) | – | 4 (1–5) | – | – |

| Size of the largest HCC nodule (mm) | – | 38 (25–74) | – | – |

| Categorical variables | Count (%) | Count (%) | OR (95% CI) | pa |

| Male gender | 89 (65.9) | 43 (84.3) | 2.78 (1.21–6.40) | 0.02 |

| Etiology of cirrhosisb | ||||

| HCV | 55 (40.7) | 15 (29.4) | 0.61 (0.30–1.21) | 0.16 |

| Alcoholic | 20 (14.8) | 30 (58.8) | 8.21 (3.95–17.09) | <0.0001 |

| NASH | 23 (17.0) | 17 (33.3) | 2.44 (1.17–5.08) | 0.02 |

| HBV | 27 (20.0) | 2 (3.9) | 0.16 (0.04–0.71) | 0.02 |

| Hemochromatosis | 9 (6.7) | 1 (2.0) | 0.28 (0.04–2.27) | 0.23 |

| Autoimmune liver diseasec | 11 (8.2) | 0 (0) | – | 0.99 |

| BCLC stage | ||||

| Stage 0-A | – | 13 (25.5) | – | – |

| Stage B | – | 20 (39.2) | – | – |

| Stage C | – | 16 (31.4) | – | – |

| Stage D | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – |

| Number of positive mSEPT9 triplicate | ||||

| Triple-negative test: 0 on 3 | 87 (64.4) | 1 (2.0) | —d | – |

| 1 on 3 | 27 (20.0) | 2 (3.9) | —d | – |

| 2 on 3 | 15 (11.1) | 8 (15.7) | —d | – |

| Triple-positive test: 3 on 3 | 6 (4.44) | 40 (78.4) | —d | – |

| Replication study: Halle (Germany) | Patients without HCC (n = 56) |

Patients with HCC (n = 47) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | OR (95% CI) | pa |

| Age (years) | 63 (60–69) | 67 (61–75) | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.03 |

| Child-Pugh score at inclusion | 6 (5–7) | 8 (6–9) | 1.29 (1.05–1.58) | 0.02 |

| mSEPT9, number of positive triplicates (0/3 to 3/3) | 0 (0–1) | 3 (3–3) | 5.81 (3.36–10.03) | <0.0001 |

| Number of HCC nodules (n) | – | 2 (1–4) | – | – |

| Size of the largest HCC nodule (mm) | – | 40 (25–70) | – | – |

| Categorical variables | Count (%) | Count (%) | OR (95% CI) | pa |

| Male gender | 45 (80.4) | 42/47 (89.4) | 2.05 (0.66–6.41) | 0.22 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis, alcoholic | 38 (67.9) | 39/47 (83.0) | 2.31 (0.90–5.94) | 0.08 |

| BCLC stage | ||||

| Stage A | – | 18 (39.1)e | – | – |

| Stage B | – | 10 (21.7)e | – | – |

| Stage C | – | 7 (15.2)e | – | – |

| Stage D | – | 11 (23.9)e | – | – |

| Number of positive mSEPT9 triplicate | ||||

| Triple-negative test: 0 on 3 | 42 (75.0) | 3 (6.4) | —d | – |

| 1 on 3 | 9 (16.1) | 4 (8.5) | —d | – |

| 2 on 3 | 3 (5.4) | 1 (2.1) | —d | – |

| Triple-positive test: 3 on 3 | 2 (3.6) | 39 (83.0) | —d | – |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IQR: interquartile range; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; mm: millimeter; BCLC: Barcelona clinic liver cancer staging classification.

Univariate logistic regression analysis.

More than one etiology of cirrhosis could be present in the same patient.

Autoimmune liver disease: autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

The odds ratio for the mSEPT9 test was reported for the continuous scale.

One patient had missing data regarding BCLC classification.

3.1. Primary Aim: Diagnostic Accuracy of the mSEPT9 Test for HCC

3.1.1. Initial Study

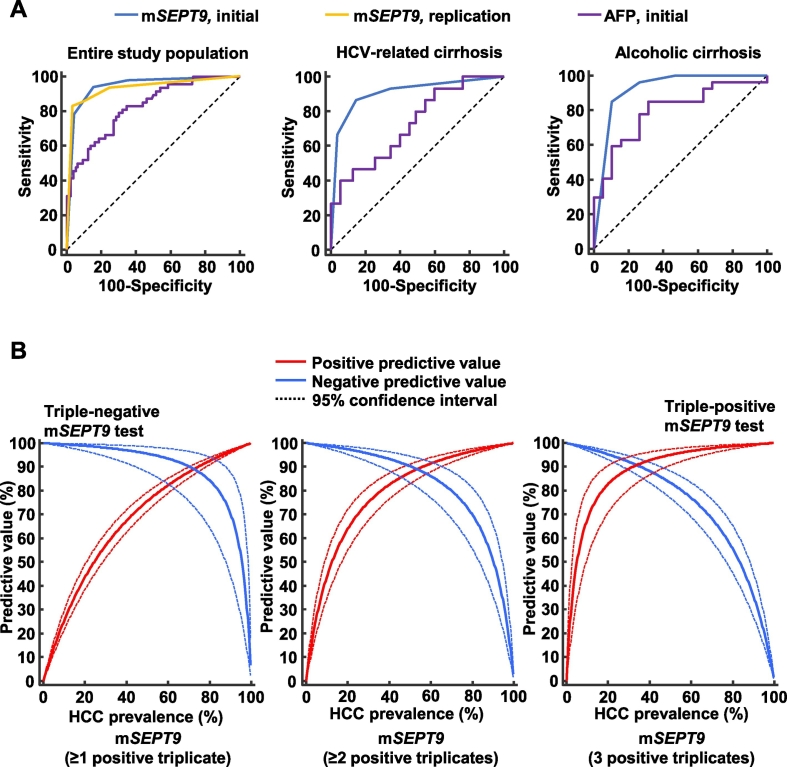

According to the ROC analysis, the mSEPT9 test exhibited high diagnostic accuracy for HCC, with an AUROC of 0.944 (95% CI, 0.900–0.970; p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 1, Fig. 2A). The optimal threshold (≥2 positive triplicates) was associated with a sensitivity of 94.1% (95% CI, 83.8–98.8) and a specificity of 84.4% (95% CI, 77.2–90.1). Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, PPVs, and NPVs for each of the mSEPT9 thresholds from the initial study are reported in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

(A) Diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis in the initial and replication studies. In the initial study, the diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test was also reported in the subgroup of patients with HCV- and alcohol-related cirrhosis. (B) Bayesian estimation of the positive and negative predictive values of the three mSEPT9 test thresholds for HCC diagnosis for varying prevalence values of hepatocellular carcinoma. Red line: positive predictive value; Blue line: negative predictive value; dashed line: 95% confidence interval.

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test for HCC diagnosis in initial and replication studies.

| Criterion | Study phase | Patients | Sensitivity (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mSEPT9 (≥1 positive triplicate) | Initial study, (Nancy) | Entire population | 98.0 (89.6–100) | 0.03 (0.004–0.20) | 98.9 (92.6–99.8) | 64.4 (55.8–72.5) | 2.76 (2.20–3.50) | 51.0 (45.3–56.7) |

| HCV-related cirrhosis | 93.3 (68.1–99.8) | 0.10 (0.02–0.70) | 97.3 (84.3–99.6) | 65.5 (51.4–77.8) | 2.70 (1.80–4.00) | 42.4 (33.3–52.1) | ||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 100 (88.4–100) | 0 (—) | 100 (—) | 50.0 (27.2–72.8) | 2.00 (1.30–3.10) | 75.0 (65.9–82.3) | ||

| Replication study, (Halle) | Entire population | 93.6 (82.5–98.7) | 0.09 (0.03–0.3) | 93.3 (82.3–97.7) | 75.0 (61.6–85.6) | 3.74 (2.4–5.9) | 75.9 (66.5–83.3) | |

| mSEPT9 (≥2 positive triplicates) | Initial study, (Nancy) | Entire population | 94.1 (83.8–98.8) | 0.07 (0.02–0.20) | 97.4 (92.7–99.1) | 84.4 (77.2–90.1) | 6.05 (4.10–9.00) | 69.6 (60.5–77.3) |

| HCV-related cirrhosis | 86.7 (59.5–98.3) | 0.16 (0.04–0.60) | 95.9 (86.6–98.8) | 85.5 (73.3–93.5) | 5.96 (3.00–11.70) | 61.9 (45.4–76.1) | ||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 96.7 (82.8–99.9) | 0.04 (0.006–0.30) | 93.7 (68.2–99.1) | 75.0 (50.9–91.3) | 3.87 (1.80–8.30) | 85.3 (73.0–92.6) | ||

| Replication study, (Halle) | Entire population | 85.1 (71.7–93.8) | 0.16 (0.08–0.3) | 87.9 (78.5–93.5) | 91.1 (80.4–97.0) | 9.53 (4.10–22.20) | 88.9 (77.5–94.9) | |

| mSEPT9 (3 positive triplicates) | Initial study, (Nancy) | Entire population | 78.4 (64.7–88.7) | 0.23 (0.10–0.40) | 92.1 (87.4–95.2) | 95.6 (90.6–98.4) | 17.65 (8.00–39.10) | 87.0 (75.1–93.7) |

| HCV-related cirrhosis | 66.7 (38.4–88.2) | 0.35 (0.20–0.70) | 91.4 (83.8–95.6) | 96.4 (87.5–99.6) | 18.33 (4.50–74.90) | 83.3 (55.0–95.3) | ||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 83.3 (65.3–94.4) | 0.19 (0.08–0.40) | 78.3 (61.5–89.0) | 90.0 (68.3–98.8) | 8.33 (2.20–31.30) | 92.6 (76.9–97.9) | ||

| Replication study, (Halle) | Entire population | 83.0 (69.2–92.4) | 0.18 (0.09–0.3) | 87.1 (78.2–92.7) | 96.4 (87.7–99.6) | 23.23 (5.90–91.20) | 95.1 (83.2–98.7) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; NLR: negative likelihood ratio; NPV: negative predictive value; PLR: positive likelihood ratio; PPV: positive predictive value.

3.1.2. Replication Study

The results from the replication study were consistent with those of the initial study with regards to all diagnostic accuracy measures (Table 2; Fig. 1). The AUROC of the mSEPT9 test to diagnose HCC was 0.930 (95% CI, 0.862–0.971; p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 1, Fig. 2A) with an optimal threshold of ≥2 positive triplicates. Based on this cut-off value, the sensitivity and the specificity were 85.1% (95% CI, 71.7–93.8) and 91.07% (95% CI, 80.4–97.0), respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, PPVs, and NPVs for each of the mSEPT9 thresholds from the replication study are reported in Table 2.

3.1.3. Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy Measures of the mSEPT9 Test for HCC

Using a random-effects meta-analysis of the results retrieved from both the initial and replication studies, we calculated the pooled effect size estimates for all diagnostic accuracy measures (Table 3). The pooled AUROC of the mSEPT9 test for HCC diagnosis was 0.940 (95% CI, 0.910–0.970; p < 0.0001) without heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; p = 0.68) or publication bias. The pooled sensitivities, specificities, PPVs, and NPVs for each of the three mSEPT9 thresholds are reported in Table 3. Considering the pooled sensitivities and specificities for each of the mSEPT9 thresholds, we used a Bayesian approach to assess the PPVs and NPVs and their 95% CIs according to an HCC prevalence ranging from 1 to 99% (Fig. 2B). A triple-negative mSEPT9 test had the highest NPV for excluding HCC, whereas a triple-positive mSEPT9 test had the highest PPV for retaining a diagnosis of HCC (Supplementary Fig. 3). A triple-positive or negative mSEPT9 test result was observed in 76% (220/289) of the patients included in the study (initial study: 134/186, 72%; replication study: 86/103, 84%).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy measures of the mSEPT9 test for HCC diagnosis based on initial and replication studies.

| Criterion | Diagnostic accuracy measure | Effect size estimation |

Heterogeneity assessment |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled effect sizea | 95% CIa | SEa | pa | Q | I2 | p | ||

| mSEPT9, (≥1 positive triplicate) | Sensitivity | 96.8 | 92.4–100 | 2.233 | <0.0001 | 0.810 | 0.00% | 0.37 |

| NPV | 97.2 | 92.1–100 | 2.585 | <0.0001 | 1.667 | 40.03% | 0.20 | |

| Specificity | 68.8 | 58.6–79.0 | 5.221 | <0.0001 | 2.020 | 50.49% | 0.16 | |

| PPV | 63.3 | 38.9–87.7 | 12.448 | <0.0001 | 23.113 | 95.67% | <0.0001 | |

| mSEPT9, (≥2 positive triplicates) | Sensitivity | 90.6 | 81.9–99.2 | 4.403 | <0.0001 | 1.749 | 42.81% | 0.19 |

| NPV | 93.3 | 84.1–100 | 4.708 | <0.0001 | 5.214 | 80.82% | 0.02 | |

| Specificity | 87.2 | 80.8–93.7 | 3.292 | <0.0001 | 1.547 | 35.35% | 0.21 | |

| PPV | 79.2 | 60.3–98.1 | 9.650 | <0.0001 | 9.784 | 89.78% | 0.002 | |

| mSEPT9, (3 positive triplicates) | Sensitivity | 80.8 | 72.4–89.1 | 4.255 | <0.0001 | 0.286 | 0.00% | 0.59 |

| NPV | 90.6 | 86.1–95.1 | 2.303 | <0.0001 | 1.417 | 29.43% | 0.23 | |

| Specificity | 95.8 | 92.6–99.1 | 1.664 | <0.0001 | 0.052 | 0.00% | 0.82 | |

| PPV | 91.5 | 83.6–99.4 | 4.028 | <0.0001 | 1.720 | 41.86% | 0.19 | |

| mSEPT9 (continuous variable) | AUROC | 0.940b | 0.910–0.970b | 0.015b | <0.0001b | 0.173 | 0.00% | 0.68 |

| Triple-negative mSEPT9 test for excluding HCC | Odds ratio | 54.66 | 18.17–164.45 | 1.754 | <0.0001 | 0.347 | 0.00% | 0.56 |

| Triple-positive mSEPT9 test for diagnosing HCC | Odds ratio | 91.53 | 37.89–221.10 | 1.568 | <0.0001 | 0.283 | 0.00% | 0.59 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; NLR: negative likelihood ratio; NPV: negative predictive value; PLR: positive likelihood ratio; PPV: positive predictive value; SE: standard error.

The pooled effect size was calculated using the generic inverse variance method according to Borenstein et al. (Borenstein et al., 2009)

The pooled effect size for AUROCS was calculated using the weighted summary area under the ROC curve under the fixed-effects model and random-effects model, as described by Zhou et al. (2009)

3.2. Secondary Aims

3.2.1. Variables Independently Associated with HCC Diagnosis

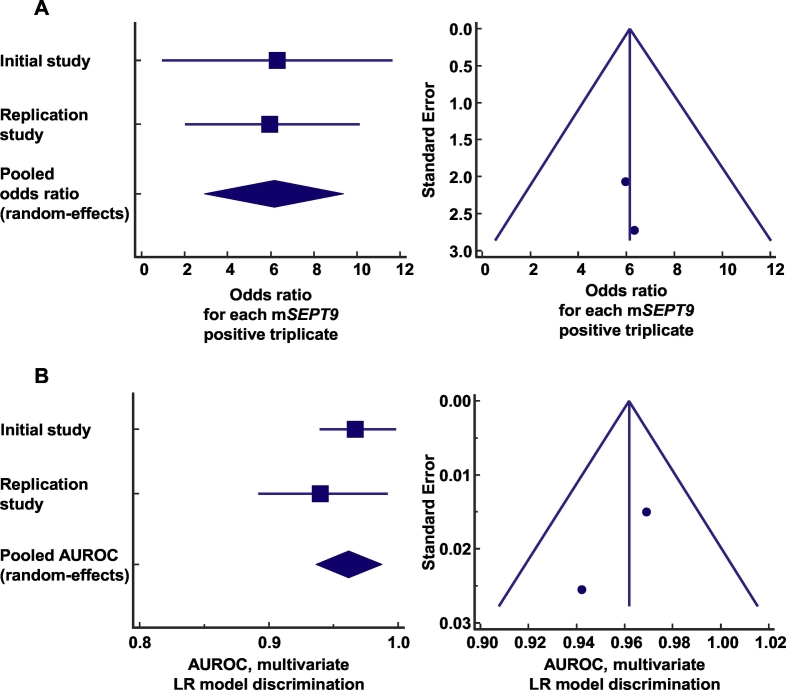

In the univariate analysis, the following variables were associated with HCC diagnosis: age, albumin, bilirubin total, prothrombin time (%), Child-Pugh score, mSEPT9, AFP, alcohol-related cirrhosis, autoimmune cirrhosis, HBV-related cirrhosis, and NASH-related cirrhosis (Table 1). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the number of positive mSEPT9 triplicates, taken as a continuous variable, was the only independent variable significantly that was associated with HCC diagnosis (OR = 6.30, for each mSEPT9 positive triplicate; 95% CI, 2.92–13.61, p < 0.0001). The multivariate logistic regression model was well calibrated with an optimal overall model fit (p < 0.0001). The AUROC associated with the discrimination of the logistic regression model in the initial study was 0.969 (95% CI, 0.930–0.989), which corroborated the results obtained from the univariate ROC analysis. Performing the same approach on the replication study, we obtained similar results, because the number of positive mSEPT9 triplicates was the only independent variable associated with the diagnosis of HCC (OR = 6.07, for each mSEPT9 positive triplicate; 95% CI, 3.25–11.35, p < 0.0001). The logistic regression model in the replication study was well calibrated with an optimal overall model fit (p < 0.0001). The model discrimination assessment in the replication study showed an AUROC of 0.942 (95% CI, 0.878–0.978). The log files of the logistic regression models are available in the Supplementary Appendix. Using a random-effects meta-analysis, the pooled odds ratio for each mSEPT9 positive triplicate was 6.15 (95% CI, 2.93–9.38, p < 0.0001, no heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, p = 0.95; and no publication bias) (Fig. 3A). Consistently, the pooled AUROC associated with the discrimination of the logistic regression models was 0.962 (95% CI, 0.937–0.987, p < 0.0001, no heterogeneity: I2 = 0%, p = 0.36; and no publication bias) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A) Meta-analysis of the odds ratios from initial and replication studies for the association between a positive mSEPT9 triplicate and the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. The calculated summary effect is denoted by the solid diamond at the bottom of the forest plots, the width of which represents the 95% confidence interval. Publication bias was estimated using a funnel plot. (B) Meta-analysis of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves associated with the discrimination of logistic regression models from initial and replication studies. The calculated summary effect is denoted by a solid diamond at the bottom of the forest plots, the width of which represents the 95% confidence interval. Publication bias was estimated using a funnel plot. AUROC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; LR: logistic regression.

3.2.2. Diagnostic Accuracy of the mSEPT9 Test for BCLC stage A HCC

Among the initial and replication studies, 33 patients had a BCLC stage A HCC and were compared with 191 HCC-free patients. To diagnose BCLC stage A HCC, the mSEPT9 test exhibited an AUROC of 0.863 (95% CI, 0.811–0.906; p < 0.0001). The sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative likelihood ratios, PPVs, and NPVs are reported in Supplementary Table 2.

3.2.3. Comparison of the Diagnostic Performance of the mSEPT9 Test with that of AFP for HCC

The mSEPT9 test exhibited significantly higher diagnostic accuracy for HCC detection compared with that of AFP (difference between AUROCs = 0.115 [95% CI, 0.042–0.187], SE = 0.04, p = 0.002). Additionally, the mSEPT9 test exhibited comparable diagnostic accuracy in the subgroup of patients with HCV- or alcohol-related cirrhosis compared with that observed in the entire patient cohort (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the mSEPT9 diagnostic accuracy was higher than that of AFP among patients with HCV-related cirrhosis (difference between AUROCs = 0.181 [95% CI, 0.029–0.334], SE = 0.08, p = 0.02) (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 2A).

3.2.4. Net Reclassification Improvement for HCC Diagnosis Using an mSEPT9-Based Strategy as Compared with an AFP-Based Strategy

We assessed the NRI of the mSEPT9-based strategy (mSEPT9 ≥ 2, the optimal ROC-defined threshold) in comparison with an AFP-based strategy (>20 ng/mL, the optimal threshold according to EASL-EORTC guidelines) and found a categorical NRI of 35.83% (95% CI, 19.06–52.61%; p < 0.0001) in favor of the mSEPT9-based strategy.

4. Discussion

The circulating cell-free DNA-based epigenetic biomarker, mSEPT9, exhibited high diagnostic accuracy for HCC, with an AUROC of 0.94, and thus could be considered a promising biomarker for diagnosing HCC among patients with cirrhosis. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, mSEPT9 was the only independent variable that was significantly associated with a diagnosis of HCC, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Our results indicated that mSEPT9 exhibited higher diagnostic accuracy compared with that using AFP, notably in HCV-related patients with cirrhosis, characterized by a lower diagnostic accuracy of AFP for HCC diagnosis (Gopal et al., 2014). Triple-positive and triple-negative mSEPT9 tests had the highest PPV and NPV for retaining or excluding a diagnosis of HCC, respectively. Patients presenting with one of these two results accounted for almost 80% (220/289) of cases and could benefit from a straightforward interpretation of their diagnostic test. Patients with two positive triplicates (15%, 42/289) were at high risk of HCC diagnosis because the specificity and the PPV corresponding to this threshold were 87.2% and 79.2%, respectively. Patients with one positive triplicate (9%, 27/289) had a moderate PPV for HCC diagnosis and could benefit from close follow-up. However, the optimal diagnostic strategy in these patients remains to be defined and should be based on prospective longitudinal studies.

Recently, a composite statistical model based on gender, age, AFP, AFP-L3, and des-γ-carboxyprothrombin (DCP) was developed for HCC diagnosis (the GALAD model) (Berhane et al., 2016). However, the diagnostic threshold of the GALAD model was not standardized and varied across cohorts, making it difficult to use at the individual patient level (Berhane et al., 2016). Notably, the EASL-EORTC guidelines do not recommend the use of AFP, AFP-L3, and DCP in routine clinical practice for HCC diagnosis (EASL-EORTC guidelines, 2012). Furthermore, based on the reported figures for the sensitivity and specificity of the GALAD model, and considering an HCC prevalence of 30%, the calculated PPVs for HCC diagnosis were 79%, 76%, and 76% in cohorts in the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan, respectively (Berhane et al., 2016). In our study, the pooled PPV for a triple-positive mSEPT9 test was 91%. Furthermore, using a Bayesian approach, PPVs for a triple-positive mSEPT9 test were > 90% over a wide range of HCC prevalence.

Septins are guanosine-5′-triphosphate-binding proteins belonging to a family of highly conserved eukaryotic proteins. They are recognized as components of the cytoskeleton, with several functions, including subcellular compartmentalization and cell division (Mostowy & Cossart, 2012; Weirich et al., 2008). Septins are implicated in the formation of filamentous complexes that are involved in various processes, including cytokinesis, vesicle trafficking, apoptosis, and maintenance of cell polarity. Disruption of SEPT9 expression resulted in incomplete cell division (Hall & Russell, 2004; Grutzmann et al., 2008). In humans, 14 septins have been described, with abnormalities in expression reported during carcinogenesis (SEPT1–7, 9, and 12) (Mostowy & Cossart, 2012). Additionally, SEPT9 acts as a tumor suppressor modulating rapid and/or uncontrolled cell division (Russell et al., 2000). Although the SEPT9 gene is expressed in tissues throughout the body, its expression is silenced or diminished by aberrant promoter methylation, which can be reactivated by treatment with azacitidine, providing evidence of potential regulation of this gene by DNA methylation (Grutzmann et al., 2008; Burrows et al., 2003). The hypomethylating agents azacitidine and decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) are currently approved for the treatment of several specific forms of myelodysplastic syndromes, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia, and are currently being investigated for use in non-hematological cancers (Kantarjian et al., 2006; Fenaux et al., 2009). Interestingly, incubation of Huh-7 HCC cells with azacitidine resulted in cell death in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Ilyas et al., 2015). These findings highlighted the role of SEPT9 as a key regulator of cell division and tumor suppression, with SEPT9 hypermethylation being associated with carcinogenesis and suggesting the potential usefulness of mSEPT9 as an HCC-related diagnostic biomarker.

Our study had several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report a promising epigenetic biomarker for HCC diagnosis in patients with cirrhosis. Second, the results from the initial and replication studies showed consistent diagnostic accuracy measures of mSEPT9. Indeed, we used a meta-analytic approach that showed no significant heterogeneity between the diagnostic accuracy measures. Importantly, the two study protocols were initiated at different time points and were independently developed by each study center. Third, we avoided misclassification bias through a robust diagnostic approach according to current guidelines for defining HCC, the use of abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan, and evidence-based care through multidisciplinary consultation meetings (Bruix & Sherman, 2011). The adjudicating physicians were blinded to the patients' results associated with the mSEPT9 test. Fourth, we used data from prospectively maintained databases, electronic health records, and the secured online platform to manage and produce multidisciplinary consultation meeting reports, thereby reducing the risk of bias. Fifth, we were able to adjust the diagnostic accuracy analysis for several potential confounders, such as age, gender, Child-Pugh score, and etiology of cirrhosis, which confirmed the mSEPT9 test as a highly accurate diagnostic biomarker of HCC. Finally, we used a second-generation, commercially-available mSEPT9 assay that requires fewer components and handling steps, and provides results within eight hours, making its use more amenable to automation for a wide range of in vitro diagnostic solutions.

Both the initial and replication studies have a phase II biomarker design with relatively small sample size and deserve to be confirmed in more extensive studies. Furthermore, the majority of patients included in the replication study had alcoholic cirrhosis. Nevertheless, we have carried out study power analysis, sensitivity analyses, and heterogeneity testing to establish the robustness and the consistency of the results obtained from both the initial and replication studies. We have initiated the SEPT9-CROSS trial (NCT03311152) to confirm the diagnostic accuracy of mSEPT9 for HCC on 440 patients with cirrhosis that were included prospectively. Although mSEPT9 showed good diagnostic accuracy for HCC detection among patients with cirrhosis, it also exhibits a cross-specificity with colorectal adenocarcinoma. Nevertheless, in patients with cirrhosis, the pre-test probability of HCC is much higher than that observed for any other type of cancer (Sorensen et al., 1998). For instance, a patient with cirrhosis is 30 times more likely to develop HCC than colorectal cancer (Sorensen et al., 1998; Komaki et al., 2017). It should be noted that when a disease has a low prevalence, the PPV can be dramatically reduced (Manrai et al., 2014). For instance, the PRESEPT trial that assessed mSEPT9 for colorectal cancer diagnosis found a very low PPV (4.82%) because of the low prevalence of the disease in the screened population (Church et al., 2014). Thus, a positive mSEPT9 test in a patient with cirrhosis should first evoke a high level of suspicion for HCC, given the high probability of HCC in this at-risk population. Surveillance cohort studies of patients with cirrhosis will allow evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of the mSEPT9 test in the screening setting.

In conclusion, mSEPT9 constitutes a promising circulating epigenetic biomarker for HCC diagnosis at the individual patient level. Future prospective studies should assess the mSEPT9 test in a screening algorithm for patients with cirrhosis to improve risk prediction and the personalized therapeutic management of HCC.

Funding Sources

University Hospital of Nancy; INSERM U1256; Wilhelm Roux Program, Medical Faculty of MLU Halle/Saale; Epigenomics AG (Berlin, Germany) kindly provided Epi proColon 2.0 CE kits. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors who have taken part in this study declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest concerning this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: AO, JLG, and JPB for the initial study and MF and AZ for the replication study; study supervision and guarantor of the article: AO and MF; data collection: AO, SR, MB, GC, PFT, AZ, and MF; mSEPT9 assay: AO, RD, DFT, TJ, and DR; methodological support: CB, AL; statistical analysis: AO, CB, AL, and PFT; data analysis and interpretation: AO, MF, JPB, and JLG; drafting the first version of the manuscript: AO, SR, MF, AZ, JPB, and JLG; report drafting, review, and approval: AO, SR, MB, GC, PFT, RD, DFT, TJ, DR, MG, AL, CB, AA, VL, MH, CR, RMRG, FN, AZ, MF, JPB, and JLG; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AO, SR, MB, GC, PFT, RD, DFT, TJ, DR, MG, AL, CB, AA, VL, MH, CR, RMRG, FN, AZ, MF, JPB, and JLG; approval of the submitted final draft: AO, SR, MB, GC, PFT, RD, DFT, TJ, DR, MG, AL, CB, AA, VL, MH, CR, RMRG, FN, AZ, MF, JPB, and JLG.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Abderrahim Oussalah had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank the patients and institutions involved in this study. We are grateful to Mrs. Sylvie Thirion for providing logistical support to the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.03.029.

Contributor Information

Abderrahim Oussalah, Email: abderrahim.oussalah@univ-lorraine.fr.

Jean-Louis Guéant, Email: jean-louis.gueant@univ-lorraine.fr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Akiyama J., Alexandre L., Baruah A. Strategy for prevention of cancers of the esophagus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014;1325:108–126. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhane S., Toyoda H., Tada T. Role of the GALAD and BALAD-2 serologic models in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and prediction of survival in patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;14:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.042. (e6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J., Rothstein H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2009. Generality of the basic inverse-variance method; pp. 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bruix J., Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruix J., Reig M., Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:835–853. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows J.F., Chanduloy S., McIlhatton M.A. Altered expression of the septin gene, SEPT9, in ovarian neoplasia. J. Pathol. 2003;201:581–588. doi: 10.1002/path.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church T.R., Wandell M., Lofton-Day C. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63:317–325. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong E.R., DeLong D.M., Clarke-Pearson D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B., Tibshirani R.J. Taylor & Francis; 1994. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag H.B. Hepatocellular carcisnoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epigenomics Epi proColon®. 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/P130001C.pdf

- Esteller M., Sanchez-Cespedes M., Rosell R., Sidransky D., Baylin S.B., Herman J.G. Detection of aberrant promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in serum DNA from non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1999;59:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenaux P., Mufti G.J., Hellstrom-Lindberg E. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal P., Yopp A.C., Waljee A.K. Factors that affect accuracy of alpha-fetoprotein test in detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutzmann R., Molnar B., Pilarsky C. Sensitive detection of colorectal cancer in peripheral blood by septin 9 DNA methylation assay. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P.A., Russell S.E. The pathobiology of the septin gene family. J. Pathol. 2004;204:489–505. doi: 10.1002/path.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X., Luo H., Krawczyk M. DNA methylation markers for diagnosis and prognosis of common cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:7414–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703577114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas A., Hashim Z., Zarina S. Effects of 5′-azacytidine and alendronate on a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line: a proteomics perspective. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015;405:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinomaJ. Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A., Ishii N., Shibata T. Mitochondrial prohibitins and septin 9 are implicated in the onset of rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;119:61–72. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H., Issa J.P.J., Rosenfeld C.S. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer. 2006;106:1794–1803. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaki Y., Komaki F., Micic D., Ido A., Sakuraba A. Risk of colorectal cancer in chronic liver diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017;86:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.009. (e5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S., Aulchenko Y.S., Van Duijn C.M., Janssens A.C.J. PredictABEL: an R package for the assessment of risk prediction models. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2011;26(4):261. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9567-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leening M.J., Vedder M.M., Witteman J.C., Pencina M.J., Steyerberg E.W. Net reclassification improvement: computation, interpretation, and controversies: a literature review and clinician's guide. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160:122–131. doi: 10.7326/M13-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrai A.K., Bhatia G., Strymish J., Kohane I.S., Jain S.H. Medicine's uncomfortable relationship with math: calculating positive predictive value. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:991–993. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercaldo N.D., Lau K.F., Zhou X.H. Confidence intervals for predictive values with an emphasis to case-control studies. Stat. Med. 2007;26:2170–2183. doi: 10.1002/sim.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran S., Martinez-Cardús A., Boussios S., Esteller M. Precision medicine based on epigenomics: the paradigm of carcinoma of unknown primary. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14(11):682–694. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostowy S., Cossart P. Septins: the fourth component of the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:183–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oussalah A., Ferrand J., Filhine-Tresarrieu P. Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin for predicting blood culture results in patients with suspected bloodstream infection: an observational study of 35,343 consecutive patients (a STROBE-compliant article) Med. (Baltimore) 2015;94 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oussalah A., Avogbe P.H., Guyot E. BRIP1 coding variants are associated with a high risk of hepatocellularcarcinoma occurrence in patients with HCV- or HBV-related liver disease. Oncotarget. 2016;8:62842–62857. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S.E., McIlhatton M.A., Burrows J.F. Isolation and mapping of a human septin gene to a region on chromosome 17q, commonly deleted in sporadic epithelial ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4729–4734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D.L., Haynes R.B. The architecture of diagnostic research. BMJ. 2002;324:539–541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7336.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M., Hyland P.L., McGregor G., Hillan K.J., Russell S.E., Hall P.A. Multimodality expression profiling shows SEPT9 to be overexpressed in a wide range of human tumours. Oncogene. 2005;24:4688–4700. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen H.T., Friis S., Olsen J.H. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998;28:921–925. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RC . 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlen M., Fagerberg L., Hallstrom B.M. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347 doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva A., Portela A., Sayols S. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61:1945–1956. doi: 10.1002/hep.27732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserkort R., Kalmar A., Valcz G. Aberrant septin 9 DNA methylation in colorectal cancer is restricted to a single CpG island. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:398. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirich C.S., Erzberger J.P., Barral Y. The septin family of GTPases: architecture and dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:478–489. doi: 10.1038/nrm2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong I.H., Lo Y.M., Zhang J. Detection of aberrant p16 methylation in the plasma and serum of liver cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1999;59:71–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Cancer Fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/

- Xu R.H., Wei W., Krawczyk M. Circulating tumour DNA methylation markers for diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Mater. 2017;16:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/nmat4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-H., DK McClish, Obuchowski N.A. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. Statistical Methods in Diagnostic Medicine. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material