Abstract

Three cases of delated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with conduction defects (OMIM 115200), limb girdle muscular dystrophy 1B (OMIM 159001) and autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy 2 (OMIM 181350), all associated with different LMNA mutations are presented. Three heterozygous missense mutations were identified in unrelated patients – p.W520R (c.1558T > C), p.T528R (с.1583С > G) and p.R190P (c.569G > C). We consider these variants as pathogenic, leading to isolated DCM with conduction defects or syndromic DCM forms with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. The mutations were not detected in the ethnically matched control group and publicly available population databases. Their de novo occurrence led to the development of the disease that was not previously detected in the extended families. Mutations at the same codons associated with laminopathies have been already reported. Differences in the clinical phenotype for p.R190P and p.T528R carrier patients are shown and compared to previous reports.

Key words: dilated cardiomyopathy, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

Background

The LMNA gene (1q21-22, MIM 150330) encodes two proteins of the nuclear envelope – lamin A and C. They are intermediate filament proteins necessary for functioning and structural integrity of the nucleus. Lamins consist of an amino-terminal head domain, a coiled-coil central rod domain and a carboxy-terminal tail domain (Fig. 1A). They form dimers by rod domains and then associate in head-to-tail polymers creating complex network conjunction with other proteins located underneath the inner membrane of the nucleus. Mutations in LMNA affect lamins’ dimerization and assembly (1, 2). It apparently leads to nuclear stability loss and inability to perform functions in its entirety. The mutations in LMNA lead to at least 10 clinically distinct phenotypes, termed laminopathies, affecting different tissues including cardiac and skeletal muscle, cutaneous, nervous and adipose tissue. There is no explicit relation between syndrome development and mutation domain localization. A number of hot spots were described in LMNA, but the mutations common for laminopathies were not found. Matching definite laminopathy symptoms with LMNA mutations brings us closer to understanding the genetic basis of the disease. Linkage analyses in affected families allow for prognosis and medication steps for mutation carriers.

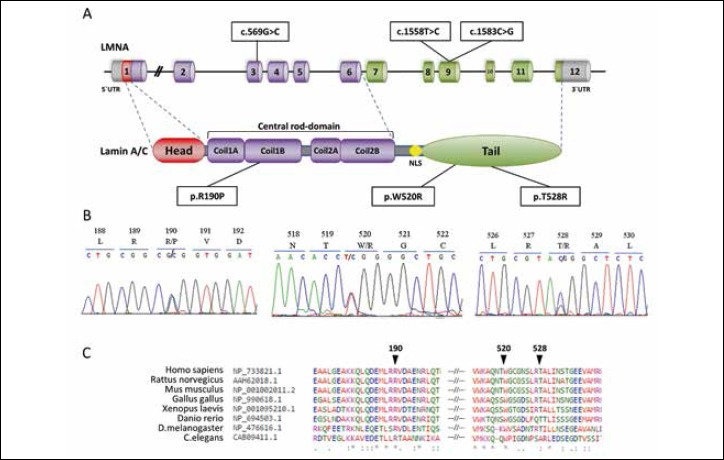

Figure 1.

LMNA mutations detected in patients. (A) Representation of mutations localization in gene and protein domains; (B) Mutation detection by DNA sequencing. Heterozygosity is revealed as two overlapping peaks; (C) Illustration of the evolutionary conservation of residues associated with identified mutations located in the coding region of LMNA by multiple alignment of various orthologous sequences.

Symbol (*) indicates identical residues in all aligned sequences, (:) - conserved substitutions, (.) - semi-conserved substitution.

This report presents three cases of laminopathy: dilatation cardiomyopathy with conduction defects (DCM, OMIM 115200), limb girdle muscular dystrophy 1B (LGMD, OMIM 159001) and autosomal-dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy 2 (EDMD, OMIM 181350) associated with the different LMNA mutations.

Methods

Patients and controls

Patients with DCM and conduction defects from the Scientific and Practical Center of Cardiology (Minsk, Belarus) were referred to Institute of Genetics and Cytology (Minsk, Belarus) for mutation analysis of the LMNA gene. The clinical diagnoses of patients included isolated DCM with conduction defects and syndromic DCM forms with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Clinical syndromes were diagnosed according to the currently established criteria (3-5).

The control group consisted of 315 ethnically matched individuals without cardiovascular diseases, physical and neurological abnormalities, a family history of DCM or sudden cardiac death. They were selected from a previously studied population cohort (6).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Clinical surveillance and genetic investigation were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the local ethics committee of the Belarusian State Medical University and the Scientific Board of the Institute of Genetics and Cytology of the National Academy of Sciences, Belarus.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was obtained from blood with phenol/chloroform extraction. Each LMNA exon and exon-intron boundaries were sequenced using the BigDye© Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit on a 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The primer sequences are available upon request.

All mutations were verified by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) in affected individuals and family members and the control group. Exons were PCR amplified and digested with endonucleases (p.R190P removes the FauI site in exon 3, p.W520R introduces the MspI site and p.T528R removes the RsaI site in exon 9).

Bioinformatics tools

Sequence variants were described according to the NCBI Reference Sequences NM_170708.3 and checked for population frequencies in Exome Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes and Genome Aggregation Database. Multiple alignment of various orthologous sequences was built with Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). To predict the effects of amino acid substitutions on motif assembly, the wild-type (GenBank: AHL67294.1) and mutated sequences of lamin A/C were analysed in the Protein secondary structure prediction server JPred4(7).

Results

LMNA exon sequencing led to the identification of different heterozygous mutations in three unrelated patients: p.R190P (c.569G > C, rs267607571), p.W520R (c.1558T > C, rs267607557) and p.T528R (с.1583С > G, rs57629361) (Fig. 1A,B). Detailed clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table I. The evolutionary conservation of residues was confirmed by multiple alignment of the region surrounding these variants against various orthologous sequences (Fig. 1C).

Table I.

Clinical characteristic of patients.

| Individual | Cardiac phenotype, (age at onset) | Systolic function, LVEF* | ECG characteristics in series | Neurological phenotype (age at onset) | Dominant muscle defeat | sCPK level, u/l (age) | PM/ICD implantation (age) | HTx (age) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | DCM (23) | 27% | SB, AVB, SSS, AF, RBBB, VES, CHB, nsVT | Subclinical (21) | Quadriceps minimal hypotrophy | 293(23) | ICD (23) | 24 |

| Patient 2 | DCM (27) | 25% | AVB, AF, LBBB, CHB, nsVT | LGMD1В (27) | The limb-girdle pattern of weakness | 784(30) | PM (27)ICD (30) | 32 |

| Patient 3 | DCM (40) | 44% | AF, AVB, CHB, sVT | AD-EDMD (5) | Proximal muscles, scapula-humeroperoneal pattern, early contractures | 471(40) | PM (40) ICD (46) |

- |

LVEF refers to the first clinical admission. AD-EDMD: autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy; AF: atrial fibrillation; AVB: atrioventricular block; CHB: complete heart block; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; ECG: electrocardiogram; HTx: heart transplantation; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LBBB: left bundle branch block; LGMD1В: limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 1B; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; nsVT: nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PM: pacemaker; RBBB: right bundle branch block; SB: sinus bradycardia; sCPK: serum creatine phosphokinase, normal level 24-190 U/L; SSS: sick sinus syndrome; sVT: sustained ventricular tachycardia; VES: ventricular extrasystoles.

Patient 1. The proband is a 24-year-old woman. The initial symptoms of DCM appeared when she was 23 (Tab. I). There was no family history of DCM or sudden cardiac death. Clinical presentation manifested in atrial fibrillation and atrial ventricular block (AVB). Complete heart block developed suddenly and quickly within three months after her first symptoms (dyspnea and weakness). No visible pathological changes of the coronary arteries were found by coronary angiography. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed dilatation of the heart chambers and systolic biventricular dysfunction. The cardioverter-defibrillator implantation and pharmacological therapy did not stop heart failure from progressing, so orthotopic heart transplantation was performed. Neurological examination showed hyperlordosis, mild quadriceps hypotrophy, hypertrophy of calf muscles without reduced limb strength. Reflexes and nerve conduction were normal. Serum creatine phosphokinase level elevated up to 293 U/L (normal range 24-190 U/L) (Tab. I).

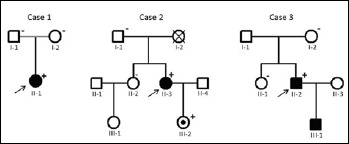

The missense p.R190P at exon 3 of the LMNA gene was identified in patient 1. First-degree relatives did not have cardiovascular disease or skeletal muscle involvement. Family genotyping showed that p.R190P occurred de novo (Fig. 2). To estimate the pathogenicity of the missense variant, population screening was performed. No mutation in LMNA gene was detected in the control group consisting of 315 adult subjects.

Figure 2.

Pedigrees of patient’s families. Squares indicate males, circles – females, open symbols – unaffected members, solid symbol – clinically affected subjects, slanted bars – deceased individuals, the black filled dot within symbol – mutation carrier. The arrow denotes the proband. Symbols (+) and (-) indicate LMNA mutation carriers and non-carriers, respectively. The absence of such symbols denotes that no DNA was available for analysis.

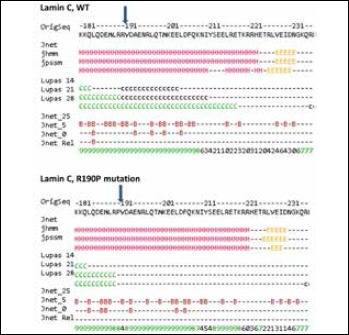

Mutation p.R190P is located in the α-helical rod domain that forms a dimeric coiled coil (CC) necessary for creating lamin network. The JPred4 server was chosen for evaluating CC formation. A low probability of regular coiled-coil assembly for P190 was shown: less than 50%. This is particularly low in comparison to R190, which has a probability of more than 90% (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Coiled coil disruption by mutation p.R190P predicted by Jpred4.

Numerous ‘H’ denote extended alpha-helical secondary structure, ‘C’- coiled coil formation with different probability for capital and small letter. Arrow indicates the position 190 and interruption of coiled coil structure due to p.R190P.

Number shows amino acid position in protein;

OrigSeq – protein sequence (GenBank: AHL67294.1);

Jnet – final secondary structure prediction for query: extended (E), helical (H) and other (-) types of secondary structure;

jhmm – Jnet HMM (hidden Markov models) profile prediction;

jpssm – Jnet PSIBLAST PSSM (Position-Specific Scoring Matrix) profile prediction.

Lupas – coiled-coil prediction for the sequence (binary predictions for each location): C = greater than 90% probability, c = 50-90% probability, (-) = less than 50% probability.

Jnet_25 – Jnet prediction of burial, less than 25% solvent accessibility;

Jnet_5 – Jnet prediction of burial, less than 5% exposure;

Jnet_0 – Jnet prediction of burial, 0% exposure, B = buried, (-) = exposed. JnetRel – Jnet reliability of prediction accuracy, ranges from 0 to 9 (bigger is better).

Patient 2. The proband is a 34-year-old woman. The first symptoms of AVB appeared when she was 27. At this period, no signs of heart dilatation were observed. During the next 3 years, heart failure symptoms progressed rapidly. Negative myocardial remodeling and progressive heart failure were observed despite the biventricular resynchronization therapy with optimal medical management and prescribed heart transplantation. The proband suffered from slight limb muscle weakness since childhood. Progressive skeletal muscle pain and weak, lower-limb muscle hypotrophy developed simultaneously with heart failure symptoms. LGMD was diagnosed when limb-girdle wasting with symmetric weakness predominantly affecting the proximal legs and arms distinctly manifested.

Patient 2 is a carrier of the p.W520R mutation. Family genotyping did not detect p.W520R in the patient’s father or sister. The mother’s death was not associated with cardiac diseases. There was no family history of DCM, skeletal muscle involvement or sudden cardiac death. The mutation was inherited by a daughter (Fig. 2), still asymptomatic except for a high serum CPK level.

Patient 3. This case is characterised by atypical clinical presentations of EDMD. Very severe muscular dystrophy and mild DCM were observed in the proband, a 47-year-old man. Wasting and weakness of the upper- and lower-limb muscles were slowly progressing from the age of 5. During adolescence, EDMD manifested through contractures of the elbows and the Achilles’ tendons; muscular dystrophy affected the arms, legs, spine, face, and neck. On the third decade of his life, a progressive proximal muscular atrophy with multiple contractures has developed. No heart disorder presented in the patient before the age of 40. The first cardiac sign was syncope caused by a complete heart block. Echocardiography showed DCM: mild left ventricular dilatation with a decrease of ejection fraction. A permanent pacemaker was implanted.

The mutation p.Т528R at exon 9 of the LMNA gene was identified in patient 3. Genetic testing of his first-degree relatives confirmed a de novo origin of the mutation. The proband has an affected child, a son diagnosed with a severe form of EDMD. Informed consent was not obtained from the son, so LMNA analysis was not performed.

Discussion

The p.R190P carrier is unique. Its detailed clinical manifestation was reported before (8). In this article, we presented data supporting its pathogenicity. We consider the variant p.R190P as pathogenic, leading to delated cardiomyopathy and conduction defects. Its de novo occurrence led to the disease development that was not previously detected in the proband family. The mutation alters an amino acid residue in the highly conserved position where another missense changes have been determined as ‘pathogenic’ before. The mutation was not detected in the control group consisting of 315 adult subjects and was absent in publicly available population databases.

Codon 190 is one of the most prevalent LMNA mutation hot spots that provoke DCM in Europe. Other amino acid replacements, p.R190Q and p.R190W, were identified in patients from several European countries, as well as South Korea and China (9-11). All of the missense mutation carriers showed nearly the same cardiac involvement, namely conduction abnormalities and/or arrhythmias, and thus the necessity of heart transplantation. We note that this case is characterised by relatively early DCM manifestation, in comparison with carriers of other amino acid substitutions in codon 190. The p.R190Q carriers were asymptomatic under 40 years of age, according to case reports described (9, 10). The p.R190W mutation manifested in a broad age range (30-58 years) or was hidden during the entire life (12, 13).

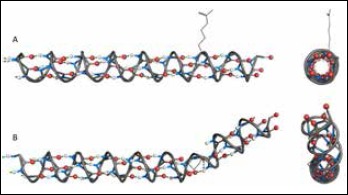

Codon 190 is located in the protein α-helical rod domain that forms a simple dimeric left-handed coiled coil (CC), which is the building block of higher-order lamin structures. The studies of LMNA mutations in the rod domain confirmed their impact on protein dimerization and assembly both in vitro and in vivo (14). In general, proline is not typical for CC and is known as the ‘helix breaker.’ We suppose its intercalation in position 190 of lamins could critically destabilize the CC structure and abolish the assembly of the normal nuclear lamina (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Representation of lamin α-helix model and simulation of amino acid substitution. The model was built with PyMol software: O atoms in red, N atoms in blue, H atoms in white and hydrogen bonds as green dotted lines. The residue side chains are not shown, except R190 and P190. (A) The α-helix of 168-199 amino acid residues: QVAKLEAALGEAKKQLQDEMLRRVDAENRLQT and side view. (B) The same α-helix with p.R190P mutation and side view. Proline curves α-helix away from the coiled coil axis: it disrupts the helical H-bond network and its side chain interferes sterically with the backbone of preceding turn.

The genetic testing allowed specifying the diagnosis of patient 2 to LGMD type 1B. This pathology form is accompanied by severe cardiomyopathy and potentially life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias presented from the first to the fourth decade of life. Our patient with LGMD predominantly suffered from cardiomyopathy with slight skeletal muscle involvement. These features became the basis for the search for LMNA mutation. We suppose the substitution of aromatic tryptophan to arginine residue, p.W520R, was crucial in LGMD development in patient 2. Codon 520 can be rightfully considered as the hot spot of LMNA gene. Several case reports associated with EDMD or LGMD have described other substitutions in this position: p.W520S (15) and p.W520G (16).

The mutation p.Т528R caused severe muscular dystrophy without heart disease manifestation for an extended period in our patient 3. The laminopathy was suspected only at age of 40 when the specific cardiac pathology manifested. The genetic investigation verified the diagnosis of autosomal-dominant EDMD type 2. We note that cardiomyopathy in other described cases of EDMD associated with p.Т528R was manifested before the age of 30. The early symptoms of heart failure were shortness of breath, atrial fibrillation and sinus tachycardia at the age of 12-23 years (17-20). Zhang et al. (2015) observed this variant in two patients with EDMD and showed positive segregation in their families, supporting pathogenicity for p.Т528R (20).

Residue W520 and T528 are composed of the lamin C-terminal domain with an immunoglobulin-like fold (Ig-fold). The W520 is a unique hydrophobic residue, which is involved in the structuring and the positioning of the largest loop of Ig-fold. Residue T528 is composed of the β-sandwich core and stabilizes its conformation (21). Substitutions in these crucial positions will change the balance of weak and strong interactions interfere with the stability, folding and biochemical properties of Ig-domain.

In summary, this article presents the LMNA mutations identified in unrelated patients suffering from DCM with conduction defects, autosomal-dominant EDMD and LGMD type 1B. We consider the missense variants p.R190P, p.Т528R and p.W520R as pathogenic, leading to dilatation cardiomyopathy. They were not detected in the ethnically matched control group and publicly available population databases. Their de novo occurrence led to the disease development that was not previously detected in the extended family. There are well-characterised mutations at the same codons associated with laminopathies. Previously reported cases with LGMD and EDMD demonstrated positive family segregation, supporting pathogenicity for p.W520R and p.T528R. Patients with LMNA mutations have a poor prognosis, a higher risk of sudden cardiac death. There is no specific treatment for laminopathies because their mechanism in humans is still unclear. The experience one can get while matching the definite laminopathy symptoms with the mutations revealed in the patients LMNA gene, in any case, bring us closer to understanding the genetic basis of disease. Linkage analyses in affected families allow for prognosis and medication steps for mutation carriers.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the families involved in this study.

References

- 1.Ben-Harush K, Wiesel N, Frenkiel-Krispin D, et al. The supramolecular organization of the C. elegans nuclear lamin filament. J Mol Biol 2009;386:1392-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bank EM, Ben-Harush K, Wiesel-Motiuk N, et al. A laminopathic mutation disrupting lamin filament assembly causes disease-like phenotypes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell 2011;22:2716-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society Of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J 2008;29:270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emery AE. Diagnostic criteria for neuromuscular disorders. The Netherlands: European Neuromuscular Centre; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narayanaswami P, Weiss M, Selcen D, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: diagnosis and treatment of limb-girdle and distal dystrophies. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Issues Review Panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine Neurology 2014;83,1453-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivitskaya L, Kushniarevich E, Danilenko N, et al. Gene polymorphism of the renin-angiotensin system in six ethnogeographic regions of Belarus. Russ J Genet 2008;44:609-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drozdetskiy A, Cole C, Procter J, Barton GJ. JPred4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:W389-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaikhanskaya T, Sivitskaya L, Danilenko N, et al. LMNA-related dilated cardiomyopathy. Oxf Med Case Rep 2014;2014:102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks SB, Kushner JD, Nauman D, et al. Lamin A/C mutation analysis in a cohort of 324 unrelated patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 2008;156:161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perrot A, Hussein S, Ruppert V, et al. Identification of mutational hot spots in LMNA encoding lamin A/C in patients with familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol 2009;104:90-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Feng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals hot spots and doubly heterozygous mutations in chinese patients with familial cardiomyopathy. BioMed Res Int 2015;ID561819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pethig K, Genschel J, Peters T, et al. LMNA mutations in cardiac transplant recipients. Cardiology 2005;103:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SKarkkainen ER, Helio T, Kaartinen M, et al. Novel mutations in the lamin A/C gene in heart transplant recipients with end stage dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2006;92:524-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruenbaum Y, Foisner R. Lamins: nuclear intermediate filament proteins with fundamental functions in nuclear mechanics and genome regulation. Annu Rev Biochem 2015;84:131-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonne G, Mercuri E, Muchir A, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy due to mutations of the lamin A/C gene. Ann Neurol 2000;48:170-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong G, Dan Z, Limeng D, et al. First report of a novel LMNA mutation in a Chinese family with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. J Genet 2014;93:843-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanna T. Cardiac features of Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy caused by lamin A/C gene mutations. Eur Heart J 2003;24:2227-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vytopil M. Mutation analysis of the lamin A/C gene (LMNA) among patients with different cardiomuscular phenotypes. J Med Genet 2003;40:132e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maggi L, D’Amico A, Pini A, et al. LMNA-associated myopathies: the Italian experience in a large cohort of patients. Neurology 2014;83:1634-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Shen H, Zhao Z, et al. Cardiac effects of the c.1583 C→G LMNA mutation in two families with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Mol Med Rep 2015;12:5056-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krimm I, Ostlund C, Gilquin B, et al. The Ig-like structure of the C-terminal domain of lamin A/C, mutated in muscular dystrophies, cardiomyopathy, and partial lipodystrophy. Structure 2002;10:811-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]