Abstract

Introduction

Angiopoietin-2 (ANG-2) is a new biomarker whose blood-serum values increase in sepsis and its expression is elevated in line with the severity of the degree of inflammation. The aim of this study was to identify the diagnostic role of ANG-2 in patients with non-surgical sepsis addmitted to an intensive care unit.

Material and methods

This was a prospective randomized study including 74 patients admitted in the Clinic of Intensive Care of the County Clinical Emergency Hospital Tirgu Mureș, divided into two groups: Group S: patients with sepsis (n=40, 54%) and Group C:control, without sepsis (n=34, 46%). ANG-2 levels were determined in both groups.

Results

From the Group S, 14 patients (35%) had positive haemocultures. ANG-2 values varied between 1 and 43 ng/mL, with an average of 6.0 ng/mL in patients without sepsis and 10.38 ng/mL in patients with sepsis (p=0.021). A positive correlation between ANG-2 and SAPS II, SOFA and APACHE II severity scores was demonstrated, as was a positive correlation between serum levels of ANG-2 and procalcitonine. ANG-2 had a 5.71% specificity and 74.36% sensitivity for diagnosis of sepsis.

Conclusions

ANG-2 serum levels were elevated in sepsis, being well correlated with PCT values and prognostic scores. ANG-2 should be considered as a useful biomarker for the diagnosis and the prognosis of this pathology.

Keywords: Angiopoietin-2, sepsis, infection

Introduction

Sepsis is a pathology frequent encountered in intensive care units, occuring as a major complication in the development of serious infections. Severe sepsis, defined as a sepsis associated with organ dysfunction [1] is associated with a high mortality rate [2] and is caused by an infection induced immune response [3]. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria, the principle indicator being a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), triggered by an infection [4,5]. The prognosis for these patients is dependant on the early establishment of the proper diagnosis and the quick initiation of antibiotic therapy [6]. Recently, special attention has been given to new biomarkers associated with sepsis. Some of these have proved to be effective in in the diagnosis and prognosis of this severe disease. Angiopoietin-2 (ANG-2) is one of these biomarkers, and has been intensively studied. It is produced by endothelial cells from Weibel-Palade corpusclues. ANG-2 induces inflammation of endothelial cells, as well as vessel regression and distruction. The blood-serum values of ANG-2 increase in sepsis and its expression is elevated in line with the severity of the degree of inflammation. However high expression of this biomarker is also found in other pathologies such as multiple mieloma [7], squamos cells carcinoma [8] or heart failure in patients on dialysis [9]. The mechanism of action of Angiopoietin-2 involves the tyrosine kinase receptor (TIE2) [10].

The aim of this study is to identify the diagnostic role of ANG-2 in patients with non-surgical sepsis admitted to an intensive care unit. We tested the hypothesis that ANG-2 has a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of sepsis and for the prognosis of this disease.

Objectives of the study were:

To asses the prognostic role of ANG-2 in sepsis.

To study the correlation between ANG-2 and procalcitonine (PCT).

-

To study the correlation between ANG-2 and the following score systems:

- APACHE II score (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation),

- SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment)

- SAPS II (Simplified Acute PhysiologyScore).

To study the correlation between ANG-2 and the requirements for vasoactive medication.

To study the correlation between ANG-2 and renal function.

Material and Methods

This is a prospective randomized study including 74 patients admitted in the Clinic of Intensive Care of the County Clinical Emergency Hospital Tirgu Mureș in the period of January to November 2014. The study was approved by the Ethics Commitee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tirgu Mureș and all the patients or their relatives were given a clear explanation of the study and gave their informed consent before randomization.

Inclusion criteria

All patient, of either sex, admitted to the intensive care ward, who were over the age of 18 years and had no associated pathology or had received any surgical intervention in the previous 72 hours, were admitted into the study.

Exclusion criteria

patients with cardiac arrest or associated pathologies that could cause expression of high levels of ANG-2.

On admission to the intensive care unit a medical history was taken and the following tests carried out:

record of status of vital signs

laboratory tests including cell blood count, creatinine, urea, coagulation parameters and liver transaminase

A clinical diagnosis was made at this point. Blood cultures and bacteriological determinations were used to confirm the diagnosis.

Blood samples were collected directly via vascular puncture after skin desinfection with betadine. The blood cultures were accomplished using separate vials for aerob germs (Standard SA) and anaerobs (Standard SN). Analyses of the blood cultures were processed using the BacT/Alert 3D (Biomerieux, France) automated haemoculture system.

APACHE II, SOFA and SAPS II severity scores were calculated and serum levels of PCT, C-Reactive protein (CRP) and ANG-2 were determined in the first 12 hours after admission.

The blood samples were frozen at -70°C and processed later.

ANG-2 expression was evaluated using the Enzyme- Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) test (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA).

PCT, CRP, the sepsis-related organ failure assessment was determined using the immunoturbidimetry method (Cobas 6000, Roche Diagnostics, Germany) and PromoKinekits for the detection, elimination and prevention of cell culture contamination (PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany).

Patients were divided into two groups: Group S: patients with sepsis (n=40, 54%) and Group C: control, without sepsis (n=34, 46%).

A diagnosis of sepsis to be accepted, all three of the following criterion had to be present:

Two clinical criteria for SIRS

PCT higher than 0.2 ng/mL

confirmed infection.

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Washington, USA), GraphPad (GraphPad Software, Inc., California, USA) and Med-Calc (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Analysis included specificity and sensibility of ANG-2 for diagnosis of sepsis, and correlation with the above mentioned parameters and death. Graphic representation of receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) were used, with determination of area under the curve (AUC). Quantitative variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Bartlets Test for equal variances. Where applicable the Mann-Whitney or Pearson tests were used for variable correlations. Pearson's chi2 test with Fisher or Yates correction were used for comparing distribution of nominal values. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

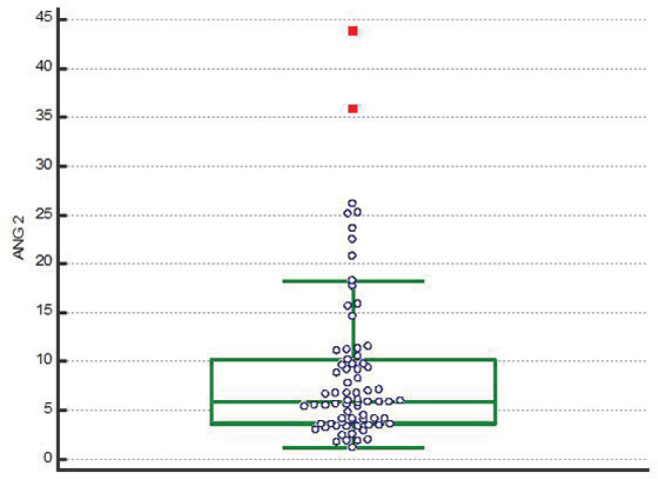

Seventy four patients were enrolled in the study, of which 40 patients (54%) fulfilled the criteria for sepsis, and 34 (46%) were included in the control group. From the Group S, 14 patients (35%) had positive haemocultures. ANG-2 values varied between 1 and 43 ng/mL, with an average of 6.0 ng/mL in patients without sepsis and 10.38 ng/mL in patients with sepsis (p=0.021) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ANG-2 values in the studied patients

Demographic and paraclinical data of the patients in the two groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and paraclinical data in the two groups of patients

| Parameter | Group -S (Patients with sepsis) (n=40, 54%) | Group- C(Control. Patients without sepsis) (n=34, 46%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, average ± SD) | 76 ± 15.87 | 68 ± 13.39 | 0.0525 |

| Gender, male (%) | 24 (60%) | 12 (35.29%) | 0.0393 |

| BMI (kg/m2, average ± SD) | 24.6 ± 8.34 | 26.9 ± 8.77 | 0.1300 |

| Days in intensive care unit TI (average ± SD) | 2 ± 4.6 | 10 ± 10.33 | < 0.0001 |

| Days under vasoactive treatment (average ± SD) | 1 ± 1.73 | 3 ± 3.35 | 0.0073 |

| Patients requiring vasoactive treatment (n, %) | 33 (82.5%) | 28 (82.23%) | 0.434 |

| Mortality (n, %) | 32 (80%) | 24 (70.59%) | 0.4197 |

| ANG-2 (ng/mL, average ± SD) | 7.37 ± 9.21 | 4.11 ± 4.34 | 0,0005 |

| PCT (ng/mL, average ± SD) | 1.525 ± 3.03 | 0.71 ± 0.75 | < 0.0001 |

| CRP (ng/mL, average± SD) | 164.4 ± 126.7 | 82.71 ± 78.98 | < 0.0001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL, average± SD) | 12.35 ± 3.09 | 11.75 ± 1.84 | 0.2762 |

| Haematocrit (%, average± SD) | 33.2 ± 8.99 | 34.05 ± 9.84 | 0.6879 |

| Leucocytes (x1000/mm3, average± SD) | 16.35 ± 12.44 | 13.95 ± 9.7 | 0.6027 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL, average± SD) | 1.84 ± 3.37 | 0.82 ± 1.88 | 0.0005 |

| Ureea (mg/dL, average± SD) | 104.9 ± 98.21 | 62.95 ± 58.68 | 0.0168 |

| APACHE II (val, average± SD) | 27 ± 8.8 | 23 ± 7.74 | 0.0152 |

| SOFA (val, average± SD) | 9 ± 3.65 | 7 ± 3.07 | 0.0616 |

| SAPS (val, average± SD) | 51.5 ± 20.18 | 42 ± 14.77 | 0.0276 |

p value calculated using Mann-Whitney test (significant for p<0,05).

A positive correlation between ANG-2 and SAPS II, SOFA and APACHE II severity scores was demonstrated, as was a positive correlation between serum levels of ANG-2 and PCT (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between ANG-2and PCT levels, severity scores, days of vasoactive medication and renal function

| Parameter | Correlation coefficient * | P value |

|---|---|---|

| PCT | -0.3049 | 0.0223 |

| APACHE II | 0.2342 | 0.0446 |

| SOFA | 0.2603 | 0.0251 |

| SAPS | 0.3321 | 0.0038 |

| Patients with vasoactive medication | 0.2353 | 0.0436 |

| Days of vasoactive medication | -0.08736 | 0.4656 |

| Creatinine | -0.256811 | 0.0560 |

| Ureea | -0.2200918 | 0.1031 |

Spearman correlation coefficient on the entire lot of patients (n=74).

The lungs were the most frequent locus of infection in the study groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Site of infection in the studied groups

| Infection localisation | Sepsis group (n=40) | No sepsis group (n=34) |

|---|---|---|

| No infection | 0 | 10 (29.41%) |

| Pulmonar Abdominal | 26 (65%) 4 (10%) | 15(44.11%) 4 (11.76%) |

| Urinar tractus Articular | 2 (5%) 0 | 2 (5.88%) 1 (2.94%) |

| Surgical wound | 0 | 1 (2.94%) |

| Central Nervous System | 0 | 1 (2.94%) |

| Cutanat | 6 (15%) | 0 |

| Undefined | 2 (5%) | 0 |

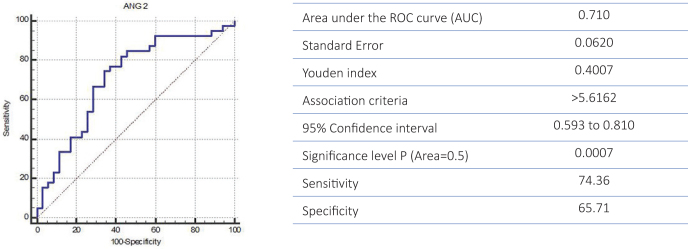

ANG-2 was both „specific” and „sensitive” in the diagnosis of sepsis: 65.71% specificity and 74.36% sensitivity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ROC curve for specificity and sensitivity of ANG 2 for diagnosis of sepsis

The cut-off value ANG-2 for diagnosis of sepsis was established at 5.61 ng/mL according to the Youden test.

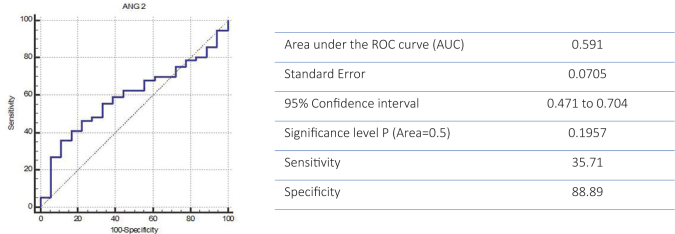

A high mortality rate of 75.67% (n=56) was recorded in those cases where ANG-2 showed a high specificity (88.89%) together with a lower sensitivity (35.71%) (p=0.195) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ROC curve for specificity and sensitivity of ANG 2 for predicting mortality rate

There was no statistically significant correlation between ANG-2 levels and the number of days on vasoactive medication (p=0.465). However, ANG-2 serum levels were correlated with the number of patients who required vasoactive treament (p=0.043). A statistically significant correlation was found between ANG-2 levels and serum levels of both creatinine and urea.

Discusions

ANG-2 and diagnosis of sepsis

This study demonstrated that ANG-2 has a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of sepsis and for the prognosis of sepsis.

ANG-2 levels obtained in this study were higher than those described by other authors. Buddingh et al [11] reported an average value of 3 ng/mL ANG-2 in healthy subjects, which increased to double values in patients with severe acute pancreatitis and severe organ dysfunction, concluding that this value was highly predictive for disease severity. In the current study, the values of ANG-2 in the control group were higher (6.0 ng/ mL), probably due to the fact that patients with infections, but without sepsis, were included in this group. Nevertheless, the statistically significant difference in ANG-2, between the two groups, proves that this biomarker can be useful for assessment of severity of infection in agreement with other stufies [12,13,14].

In the current study, a cut-off value of 5.61 ng/mL was the borderline value below which the probability of infection was very low, this being similar to previously reported value of 6.0 ng/mL, reported by Buddingh et al [11] reported as representing the cutoff point above which being indicative of patients with an infection.

Several authors reported a good correlation between ANG-2 levels and pulmonary function in patients treated with high doses of interleukine-2 [15].

ANG-2, duration of stay in ICU and the requirements for vasoactive medication

Analysis of the results of the present study showed that patients without sepsis were retained intensive care units longer that those with sepsis. This apparent anomaly may be explained by the fact that sepsis patients presented a higher mortality rate, death occuring frequently in the first days after admission. A similar trend was noticed in regards to the number of days patients were maintained on vasoactive treatment.

An increase in cardiac output, related to a descrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction and hypotension has been associated with an increase of serum levels of ANG-2 [16].

ANG-2 levels and renal function

The present study was unable to demonstrate a clinically significant correlation between ANG-2 and renal function in contradiction to the report by Tsai et al which showed ANG to be an appropriate predictor of the unfavourable development of renal failure eventhough in the current stage the exact pathophysiological mechanism for this effect has not been clearly identified [17].

ANG-2 levels and severity scores

Another objective of the study was to demonstrate the correlation between ANG-2 and the severity scores. We proved that ANG-2 values correlate very well with the APACHE II, SOFA and SAPS severity scores, used in the study. This supports the role ANG-2 as a biomarker for prognosis of severe sepsis, all be it that the sensitivity of this parameter for prediction of death is not high (35%). Again, this low value may reflect the fact that patients without sepsis have a high mortality rate (70.59%) due to other pathologies.

AGT-2 differentially regulates angiogenesis through tyrosine kinase-2 receptors (TIE2) and integrin signalling and several studies have demonstrated that not only the ANG-2 levels, but also TIE2 levels, may be usefull in determining the prognosis of patients with severe sepsis, as the vascular modelling determined by ANG-2 is well correlated with the levels of TIE2 [18].

Conclusions

ANG-2 serum levels were elevated in sepsis, being well correlated with PCT values and prognostic scores. ANG-2 is both high specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of sepsis, and should be considered as a useful biomarker for the diagnosis and the prognosis of this pathology.

Acknowledgements

This paper is supported by the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development (SOP HRD), financed from the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government under the contract number POSDRU/159/1.5/S/133377.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including The Pediatric Subgroup; Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsisand septic shock: 2012. Critical Care Care. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russel JA.. The current management of septic shock. Minerva Medica. 2008;99:431–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutschman CS, Tracey KJ.. Sepsis: Current dogma andnewperspectives. Immunity. 2014;40:463–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jui J. Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. Septic Shock; pp. 1003–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger RH, Levy MM, Rhodes A. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sisand septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Care. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bone R, Balk R, Cerra F. et al. Definitions for sepsisand organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappa CA, Tsirakis G, Samiotakis P. et al. Serum levels of angiopoietin-2 are associated with the growth of multiple myeloma. Cancer Invest. 2013;31:385–9. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2013.800093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C, Sun CJ, Fan JC. et al. “Angiopoietin-2 expression is correlated with angiogenesis and overall survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2013;30:571. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shroff RC, Price KL, Kolatsi-Joannou M. et al. Circulating angiopoietin-2 is a marker for early cardiovascular disease in children on chronic dialysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeansson M, Gawlik A, Anderson G. et al. Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. J Clin Clin. 2011;121:2278–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI46322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buddingh KT, Koudstaal LG, van Santvoort HC. et al. Early angiopoietin-2 levels after onset predict the advent of severe pancreatitis, multiple organ failure, and infectious complications in patients with acute pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang K, Bhandari V, Giuliano JS Jr O, Hern CS, Shattuck MD, Kirby M.. Angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2 and bicarbonate as diagnostic biomarkers in children with severe sepsis. PLoS One. 2014;25:e108461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mearelli F, Fiotti N, Altamura N. et al. Heterogeneous models for an early discrimination between sepsis and non-infective SIRS in medical ward patients: a pilot study. Intern Emerg Emerg. 2014;9:749–57. doi: 10.1007/s11739-013-1031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giuliano JS Jr, Tran K, Li FY, Shabanova V, Tala JA, Bhandari V.. The temporal kinetics of circulating angiopoietin levels in children with sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:e1–8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182a553bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gores KM, Delsing AS, Kraus SJ. et al. Plasma Angiopoietin-2 concentrations are related to impaired lung function and organ failure in a clinical cohort receiving high-dose interleukin 2 therapy. Shock. 2014;42:115–20. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziegler T, Horstkotte J, Schwab C. et al. Angiopoietin-2 mediates microvascular and hemodynamic alterations in sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2013;pii:66549. doi: 10.1172/JCI66549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai YC, Chiu YW, Tsai JC. et al. Association of angiopoietin-2 with renal outcome in chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2014;3(9):e108862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felt M, Luck R, Schering A. et al. Angiopoietin-2 differentially regulates angiogenesis through TIE2 and integrin signaling. J Clin Clin. 2012;122:1991–2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI58832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]