Abstract

Context

Complicated grief is a debilitating disorder associated with important negative health consequences, but the results of existing treatments for it have been disappointing.

Objective

To compare the efficacy of a novel approach, complicated grief treatment, with a standard psychotherapy (interpersonal psychotherapy).

Design

Two-cell, prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial, stratified by manner of death of loved one and treatment site.

Setting

A university-based psychiatric research clinic as well as a satellite clinic in a low-income African American community between April 2001 and April 2004.

Participants

A total of 83 women and 12 men aged 18 to 85 years recruited through professional referral, self-referral, and media announcements who met criteria for complicated grief.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to receive interpersonal psychotherapy (n= 46) or complicated grief treatment (n= 49); both were administered in 16 sessions during an average interval of 19 weeks per participant.

Main Outcome Measure

Treatment response, defined either as independent evaluator-rated Clinical Global Improvement score of 1 or 2 or as time to a 20-point or better improvement in the self-reported Inventory of Complicated Grief.

Results

Both treatments produced improvement in complicated grief symptoms. The response rate was greater for complicated grief treatment (51%) than for interpersonal psychotherapy (28%; P =.02) and time to response was faster for complicated grief treatment (P =.02). The number needed to treat was 4.3.

Conclusion

Complicated grief treatment is an improved treatment over interpersonal psychotherapy, showing higher response rates and faster time to response.

Many Physicians are Uncertain about how to identify bereaved individuals who need treatment, and what treatments work for bereavement-related mental health problems.1 Bereavement-related major depressive disorder is a well-recognized consequence of loss.2,3 Complicated grief also occurs in the aftermath of loss but needs to be differentiated from depression. Complicated grief can be reliably identified by administering the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG)4 more than 6 months after the death of a loved one. Key features of complicated grief5,6 include (1) a sense of disbelief regarding the death; (2) anger and bitterness over the death; (3) recurrent pangs of painful emotions, with intense yearning and longing for the deceased; and (4) preoccupation with thoughts of the loved one, often including distressing intrusive thoughts related to the death.

Avoidance behavior is also frequent and entails a range of situations and activities that serve as reminders of the painful loss. Studies indicate that treatments for bereavement-related depression show minimal effects on complicated grief symptoms.7,8 Complicated grief bears some resemblance to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although again, there are important differences.9 Factor analysis shows that symptoms of complicated grief load separately from both depression and anxiety.10,11 Comparisons of complicated grief, major depression, and PTSD are listed in Table 1. Co-occurrence of complicated grief with major depressive disorder and PTSD is also common. Prior studies indicate that rates of complicated grief co-occurring with major depressive disorder range from 21%5 to 54%4 and co-occurring with PTSD range from 30%12 to 50%.13

Table 1.

Similarities and Differences Between Complicated Grief and DSM-IV Disorders

| Similarities Between Complicated Grief and DSM-IV Disorders | |

| Major Depression | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| Sadness, loss of interest Loss of self-esteem Guilt |

Triggered by traumatic event Sense of shock, helplessness Intrusive images Avoidance behavior |

|

| |

| Differences Between Complicated Grief and DSM-IV Disorders | |

| Major Depression | Complicated Grief |

|

| |

| Pervasive sad mood | Sadness related to missing the deceased |

|

| |

| Loss of interest or pleasure | Interest in memories of the deceased maintained; longing and yearning for contact; pleasurable reveries |

|

| |

| Pervasive sense of guilt | Guilt focused on interactions with the deceased |

|

| |

| Rumination about past failures or misdeeds | Preoccupation with positive thoughts of the deceased |

|

| |

| Intrusive images of the person dying | |

|

| |

| Avoidance of situations and people related to reminders of the loss | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | Complicated Grief |

|

| |

| Triggered by physical threat | Triggered by loss |

|

| |

| Primary emotion is fear | Primary emotion is sadness |

|

| |

| Nightmares are very common | Nightmares are rare |

|

| |

| Painful reminders linked to the traumatic event; usually specific to the event | Painful reminders more pervasive and unexpected |

|

| |

| Yearning and longing for the person who died Pleasurable reveries |

|

Abbreviation: DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Although it is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), complicated grief is a source of significant distress and impairment and is associated with a range of negative health consequences.14–16 Prevalence rates are estimated at approximately 10% to 20% of bereaved persons.17,18 Approximately 2.5 million people die yearly in the United States.19 Estimates suggest each death leaves an average of 5 people bereaved, suggesting that more than 1 million people per year are expected to develop complicated grief in the United States.

Given observations regarding the specificity and clinical significance of complicated grief symptoms, including the lack of response to standard treatments for depression,20,21 we developed a targeted complicated grief treatment (CGT). Since complicated grief includes depressive symptoms such as sadness, guilt, and social withdrawal, we used a framework for the treatment based on previous research with interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for grief-related depression.22 In view of the presence of PTSD symptoms of disbelief, intrusive images, and avoidance behaviors, as well as unique symptoms related to the loss (eg, yearning and longing for the deceased), we modified IPT techniques to include cognitive-behavioral therapy–based techniques for addressing trauma. We used cognitive strategies for working with loss-specific distress. As suggested by results of a comparison of the 2 methods,23 we have previously found that IPT and cognitive-behavioral therapy lend themselves to integration.24,25 Following completion of an open trial of CGT,21 we report here the results of a randomized controlled trial comparing CGT with standard IPT. We hypothesized that CGT would be superior to IPT with respect to overall response rates and time to response, with CGT producing a more rapid and greater resolution of complicated grief symptoms than IPT.

METHODS

Study Design

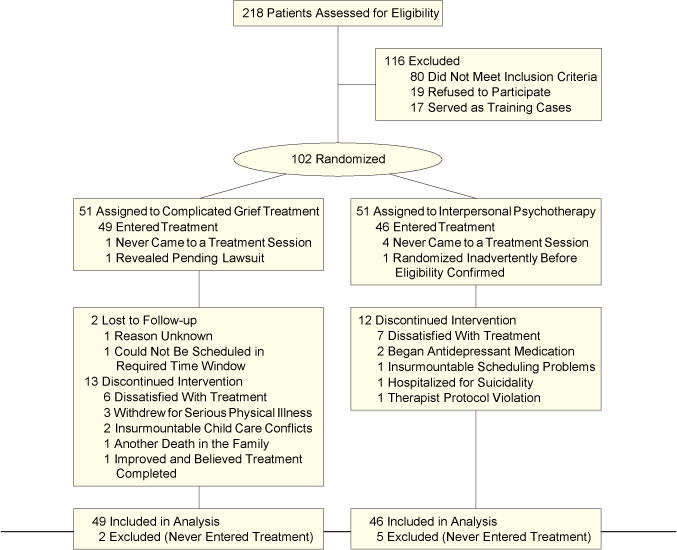

Patients who met criteria for complicated grief, defined as score on the ICG of at least 30, were recruited to a university-based clinic. To include a broad range of participants, we also enrolled study participants at a clinic attended by primarily low-income African American patients. Race was assessed by self-report. We obtained this information as part of a concerted effort to include low-income minorities in our study. The originally proposed sample size was 60. Participants were randomly assigned to receive CGT or IPT in a ratio of 1:1. Randomization was stratified by treatment site and, within site, by violent (accident, homicide, or suicide) vs nonviolent death of a loved one. A blinded randomization number was assigned using a computerized random number generator without blocking. Decisions regarding eligibility were based primarily on independent evaluator assessment and always made by the study team prior to disclosure of the treatment assignment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants Through the Trial

Treatment was provided in approximately 16 sessions over a 16- to 20- week period. Three additional sessions could be added in the event of a second death. Time could be extended if there was a serious life event (eg, hospitalization for medical illness, severe stressor.) Patients whose treatment coincided with the attacks of September 11, 2001, were offered an extra session to discuss their reaction. Treatment could be shorter if both therapist and patient agreed that the patient had successfully completed the course of treatment. Posttreatment assessment was obtained on completion of treatment by evaluators blinded to randomized treatment assignment. For early dropouts, therapists provided an estimated global improvement score and a written paragraph justifying their rating. The independent evaluator reviewed this information with all available ratings prior to finalizing the response rating. Study nonresponders were either treated openly or referred to geographically convenient or preferred outside treatment. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Participants were enrolled between April 2001 and April 2004.

Participants

Bereaved individuals recruited via professional referral, media advertisement, and self-referral gave oral informed consent for a brief screening interview by telephone (n=405) or in person (n=12). A subgroup (n=26) was recruited from the clinic with predominantly low-income African American patients. Individuals who screened positive (n=329) on the ICG and signed written informed consent (n=218) were assessed for eligibility, initial symptom ratings, and drug stabilization for patients taking antidepressant medication (n=92). Patients were permitted to take medication for depression during the study if (1) medication management was transferred to the study pharmacotherapist and (2) medication use was stable for a minimum of 3 months, with at least 6 weeks at the same dose. The study pharmacotherapist made a judgment about adequacy of pharmacotherapy and adjusted medications as necessary, prior to randomization.

Inclusion required a score of at least 30 on the ICG at least 6 months after the death of a loved one and judgment by the independent evaluator that complicated grief was the most important clinical problem. Individuals with current substance abuse or dependence (past 3 months), history of psychotic disorder or bipolar I disorder, suicidality requiring hospitalization, pending lawsuit or disability claim related to the death, or concurrent psychotherapy were excluded.

Therapists

All therapists were master’s- or doctoral- level clinicians who had at least 2 years of psychotherapy experience and who underwent extensive training and certification in either IPT or CGT. Certification entailed completion of 2 treatment cases in a manner judged competent by K.S. (for CGT) or E.F. (for IPT). Therapists received ongoing group supervision, separately for IPT and CGT, throughout the study period. Selected audiotapes or videotapes were used in supervision sessions as a part of the discussion. Therapy sessions were audiotaped for adherence and competence ratings, performed on a randomly selected subset of sessions.

Treatment Conditions

Interpersonal psychotherapy is a proven efficacious treatment, well studied for the treatment of depression.26,27 Our group has done extensive research using this treatment, and therapists in this study had a strong allegiance to IPT. Interpersonal psychotherapy was delivered as described in a published manual,28 using an introductory, middle, and termination phase. During the introductory phase, symptoms were reviewed and identified and an interpersonal inventory was completed. Interpersonal psychotherapists used a grief focus, sometimes accompanied by a secondary focus on role transition or interpersonal disputes. The relationship between symptoms and grief and other interpersonal problems was discussed. The middle phase was used to address grief and other interpersonal problems, as indicated. The IPT therapist helped patients to arrive at a more realistic assessment of the relationship with the deceased, addressing both its positive and negative aspects, and encouraged the pursuit of satisfying relationships and activities. In the termination phase, treatment gains were reviewed, plans were made for the future, and feelings about ending treatment were discussed.

Complicated grief treatment, delivered according to a manual protocol, also included an introductory, middle, and termination phase. In the introductory phase, the therapist provided information about normal and complicated grief and described the dual-process model of adaptive coping, entailing both restoration of a satisfying life and adjustment to the loss.29 This model posits that grief proceeds optimally when attention to loss and restoration alternate, while coping with both processes proceeds more or less in concert. Thus, in addition to discussion of the loss, the introductory phase of CGT included a focus on personal life goals. In the middle phase, the therapist addressed both processes in tandem. Similar to IPT, the termination phase focused on review of progress, plans for the future, and feelings about ending treatment.

In contradistinction to IPT, however, traumalike symptoms were addressed using procedures for retelling the story of the death and exercises entailing confrontation with avoided situations, modified from imaginal and in vivo exposure used for PTSD.30,31 We called the retelling procedure “revisiting.” To conduct a revisiting exercise, the therapist asked patients to close their eyes and tell the story of the death. The therapist tape-recorded the story, and periodically asked the patient to report distress levels. The patient was given the tape to listen to at home during the week. Distress related to the loss (eg, yearning and longing, reveries, fears of losing the deceased forever) was targeted using techniques to promote a sense of connection to the deceased. These included an imaginal conversation with the deceased and completion of a set of memories questionnaires, primarily focused on positive memories, though also inviting reminiscence that was negative. The imaginal conversation was conducted with the patient’s eyes closed. The patient was asked to imagine that he/she could speak to the person who died and that the person could hear and respond. The patient was invited to talk with the loved one and then to take the role of the deceased and answer. The therapist guided this “conversation” for 10 to 20 minutes. For the restoration focus, patients defined personal life goals using a technique derived from motivational enhancement therapy.32 Patients were encouraged to consider what they would like for themselves if their grief was not so intense. The therapist then helped patients identify ways to know that they were working toward their identified goals. Concrete plans were discussed and the therapist encouraged the patient to put these into action. Standard IPT procedures targeting role transition and/or interpersonal disputes were also used, as needed, to encourage patients to reengage in meaningful relationships. More detailed information describing the treatment is available from the authors.

Assessment Procedures

Independent evaluators were experienced master’s- or doctoral-level clinicians trained for reliability on rating instruments and monitored throughout the study. Evaluators were blinded to treatment assignment, and study staff closely monitored procedures to maintain the blinding. Independent evaluators conducted assessments prior to as well as after treatment. Additionally, for randomized participants who dropped out after at least 1 treatment session, a Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) Scale score was generated. To do this, therapists provided a global improvement rating and a brief narrative justifying their rating, without including information related to the treatment. The independent evaluator reviewed the rating and narrative as well as available participant self-report assessments from the final session to finalize the CGI score. The CGI Scale33 is a single Likert- type rating from 1 to 7 where 1 through 3 indicate very much, much, and minimally improved, respectively; 4 indicates no change; and 5 through 7 indicate minimally, much, and very much worse, respectively.

Pretreatment assessment included the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV,3 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,35 Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety,36 structured clinical interviews for complicated grief and for suicidality, and screening medical evaluation. We diagnosed major depression without making an effort to discriminate grief from depression. Self-reported measures included the ICG4 and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale.37 The Beck Depression38 and Anxiety39 Inventory scales as well as the ICG and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale were completed at treatment sessions. Responder status was determined in 2 different ways: independent evaluator score of 2 or lower on the CGI and self-reported improvement of at least 20 points (2 SDs above baseline mean) on the ICG.

Statistical Analyses

The study was designed to address the question of whether CGT produced better results than standard IPT for the treatment of complicated grief. To answer this question, we examined rate of response, defined using either an interviewer (CGI) or a self-reported (ICG) measure for all randomized patients who attended at least 1 treatment session (modified intention-to-treat study group, n= 95).

Data were first descriptively analyzed to check range and distribution of all variables. We further checked to ensure equivalent distribution of scores across study groups. Baseline comparisons included all demographic and clinical variables.

Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel general association analyses were used to compare CGI responder rates for IPT and CGT. Statistical significance was defined as P<.05 with a 2-tailed test. We used a survival analytic strategy to compare time to response using the ICG criterion. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to investigate time to response and proportion surviving by treatment groups. Wilcoxon x2 tests were used to assess differences in survival curves. We further calculated number needed to treat as 1 divided by the proportion responding in CGT-IPT as an estimate of the number of patients who would need to be given CGT for 1 of them to achieve a response outcome who would not have achieved it with IPT. For most efficacious treatments, the number needed to treat falls between 2 and 4.40

Continuous measures were evaluated using end-point analysis with baseline score as covariates in both modified intention-to-treat and completer analyses for the self-reported measures, ICG, Work and Social Adjustment Scale, and Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventory scales. Interview- rated Hamilton Depression and Anxiety scores were obtained only at baseline and posttreatment assessment points and so are available only for completers.

To examine the possible difference in response by baseline measures, a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, stratified by treatment, was used. To examine differential treatment response in different subgroups, a Breslow-Day test41 was used, stratifying by group. A significant result indicates that a differential treatment X group interaction exists. SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline, Site, and Stratum Analyses

There were no significant differences in demographic measures or baseline ICG scores between the 2 randomized groups (Table 2). Because no significant stratum effect for site or type of death was observed, we aggregated data across strata.

Table 2.

Pretreatment Comparison of Treatment Groups

| Complicated Grief Treatment (n = 49)* | Interpersonal Therapy (n = 46)* | Value x2 or t | df | Value P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 49.4 (13.9) | 47.3 (11.3) | 0.80 | 93 | .42 |

| Male | 6 (12) | 6 (13) | 0.01 | 1 | .91 |

| White | 36 (75) | 36 (78) | 0.14 | 1 | .71 |

| Education | |||||

| <12 y | 12 (27) | 7 (16) | 2.61 | 3 | .46 |

| Partial college | 17 (38) | 16 (36) | |||

| 4-y college | 8 (18) | 11 (25) | |||

| Postgraduate | 8 (18) | 12 (27) | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Never married | 9 (18) | 9 (20) | 3.25 | 3 | .36 |

| Married | 12 (24) | 18 (39) | |||

| Separated/divorced | 16 (33) | 9 (20) | |||

| Widowed | 12 (24) | 10 (22) | |||

| Relationship of deceased | |||||

| Spouse/partner | 17 (35) | 9 (20) | 4.44 | 3 | .22 |

| Parent | 12 (24) | 14 (30) | |||

| Child | 10 (20) | 16 (35) | |||

| Other | 10 (20) | 7 (16) | |||

| Violent death of deceased | 16 (33) | 15 (33) | 0.11 | 1 | .99 |

| Years since loss, median (range)† | 2.1 (0.5–36.6) | 2.5 (0.5–22.3) | −0.08 | 93 | .94 |

| Major depressive disorder | |||||

| Current | 22 (45) | 19 (41) | 0.13 | 1 | .72 |

| Lifetime | 33 (67) | 33 (72) | 0.22 | 1 | .64 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | |||||

| Current | 24 (49) | 21 (46) | 0.11 | 1 | .75 |

| Lifetime | 27 (55) | 24 (52) | 0.08 | 1 | .77 |

| Inventory of Complicated Grief score, mean (SD)‡ | 45.8 (8.0) | 44.2 (9.9) | 0.87 | 93 | .39 |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score, mean (SD)§ | 24.5 (9.2) | 22.3 (8.9) | 1.18 | 93 | .24 |

| Structured Interview Guide for Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety score, mean (SD)I | 19.7 (7.8) | 18.9 (7.9) | 0.49 | 93 | .63 |

Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise noted.

Natural log transformation prior to statistical comparison.

Mean (SD) scores for healthy controls are reported as 10.28 (6.6); mean (SD) score in a bereaved population is 17.74 (12.4).4

Treatment completion rates (73% for CGT and 74% for IPT) did not differ across groups. Mean number of CGT sessions for completers was 16 (range, 7-19). Mean number of IPT sessions was 16 (range, 15-16). Mean time to completion of CGT was 19.4 weeks. Mean time to completion of IPT was 18.4 weeks. Mean number of sessions prior to dropout for CGT was 5.9 (SD, 3.7; range, 1-12) and for IPT was 4.3 (SD, 2.6; range, 1-8). Three patients in CGT each had 3 additional sessions to deal with a second death and 2 had 1 additional session. Two had extra sessions to address an intercurrent medical problem (kidney stone and blepharospasm) and 1 had an extra session to discuss the September 11 attacks. Three patients ended treatment early with the agreement of their therapists. A total of 6 CGT and 3 IPT patients had treatment lasting more than 20 weeks. Twenty IPT (43%) and 23 CGT (47%) patients continued to take antidepressant medication begun prior to randomization.

Responder Analyses

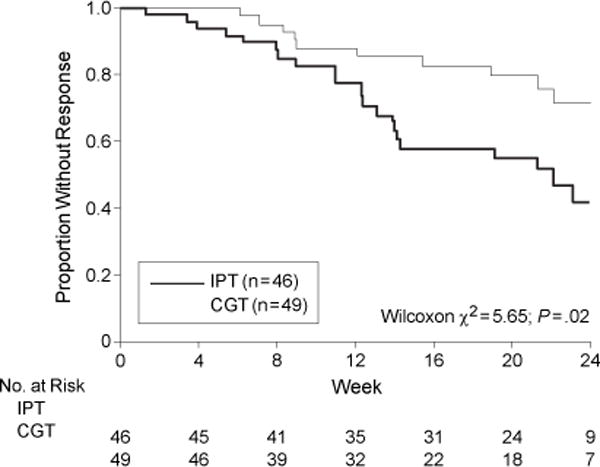

Using the independent evaluator criterion of a CGI score of 2 (much improved) or 1 (very much improved), rate of response in the modified intention-to-treat sample was greater for CGT than for IPT among all randomized participants; 51% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37%-65%) treated with CGT responded compared with 28% (95% CI, 15%-41%) treated with IPT (x2= 5.07; P =.02; cohort relative risk [RR], 1.69 [95% CI, 1.03-2.77]). Among completers, 66% (95% CI, 50%-82%) vs 32% (95% CI, 16%-48%) responded ( ; P = .006; cohort RR, 2.03 [95% CI, 1.16-3.49]). The number needed to treat was 4.3 for modified intention to treat and 2.9 for completers. Median time to response using the self-report (ICG) criterion was shorter for CGT than for IPT (Figure 2) (Wilcoxon ; P =.02).

Figure 2. Survival Analysis (Time to Response).

Response was defined as a decrease in the Inventory of Complicated Grief score of 20 points or more. CGT indicates complicated grief treatment; IPT, interpersonal psychotherapy.

Results for Continuous Measures

Table 3 shows results for the ICG, Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory, and Work and Social Adjustment Scale. In the modified intention-to-treat analysis, outcome was marginally better for CGT than for IPT. Results for completers showed significantly better outcome for CGT with medium effect size differences on the ICG, Beck Depression Inventory, and Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Table 3.

Posttreatment Scores and Group Effect From End-point Analyses With Pretreatment as a Covariate

| No. (%) | F | df | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated Grief Treatment | Interpersonal Psychotherapy | ||||

| Modified Intention to Treat | |||||

| Inventory of Complicated Grief | n = 49 | n = 46 | |||

| Pretreatment | 45.8 (8.0) | 44.2 (9.9) | |||

| Posttreatment | 28.6 (16.2) | 31.4 (12.9) | |||

| Difference | 17.2 (15.3) | 12.8 (11.9) | 1.86 | 92 | .18 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | n = 47 | n = 45 | |||

| Pretreatment | 17.5 (12.0) | 15.4 (10.2) | |||

| Posttreatment | 9.3 (10.7) | 9.4 (8.7) | |||

| Difference | 8.2 (8.7) | 6.0 (9.3) | 0.69 | 89 | .41 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | n = 47 | n = 45 | |||

| Pretreatment | 23.9 (10.3) | 22.4 (9.8) | |||

| Posttreatment | 13.4 (10.0) | 15.2 (10.8) | |||

| Difference | 10.4 (9.6) | 7.2 (7.2) | 2.70 | 89 | .10 |

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale | n = 49 | n = 46 | |||

| Pretreatment | 20.3 (10.1) | 20.5 (9.6) | |||

| Posttreatment | 12.5 (10.5) | 16.2 (11.0) | |||

| Difference | 7.8 (11.3) | 4.2 (9.5) | 3.59 | 92 | .06 |

| Treatment Completers | |||||

| Inventory of Complicated Grief | n = 35 | n = 34 | |||

| Pretreatment | 46.4 (8.4) | 43.4 (9.8) | |||

| Posttreatment | 25.8 (15.7) | 30.6 (13.8) | |||

| Difference | 20.6 (15.0) | 12.8 (10.7) | 5.18 | 66 | .03 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | n = 35 | n = 34 | |||

| Pretreatment | 17.6 (12.5) | 14.5 (9.8) | |||

| Posttreatment | 8.1 (10.4) | 8.7 (9.5) | |||

| Difference | 9.5 (7.3) | 5.8 (9.5) | 1.94 | 66 | .17 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | n = 35 | n = 34 | |||

| Pretreatment | 24.6 (10.8) | 20.9 (9.8) | |||

| Posttreatment | 11.9 (10.0) | 13.6 (11.4) | |||

| Difference | 12.7 (9.8) | 7.3 (5.6) | 5.92 | 66 | .02 |

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale | n = 35 | n = 34 | |||

| Pretreatment | 21.5 (10.9) | 20.1 (10.0) | |||

| Posttreatment | 11.0 (10.4) | 15.1 (11.1) | |||

| Difference | 10.4 (11.2) | 5.0 (9.9) | 4.47 | 66 | .04 |

Attrition

Early treatment discontinuation occurred for 13 (27%) of 49 CGT and 12 (26%) of 46 IPT participants. Reasons for discontinuation differed; 6 CGT patients (12%) considered the treatment too difficult and/or did not believe that telling the highly painful story of the death could help them. An additional 7 participants (14%) discontinued CGT for serious medical illness (n= 3; after sessions 4, 10, and 12), insurmountable child care conflicts (n= 2; after sessions 3 and 5), a death in the family (n=1; after session 6), and sufficient improvement (n=1; after session 12). Also of note, 5 CGT patients who completed the treatment refused participation in the imaginal exposure exercise because they considered it too difficult.

For IPT, 7 (15%) of 46 left treatment dissatisfied because of perceived lack of effectiveness. Five additional IPT patients (11%) discontinued treatment. Reasons included scheduling problems (n= 1; after session 8), hospitalization for active suicidal ideation (n= 1; after session 5), beginning antidepressant medication (n= 2; after sessions 10 and 12), and withdrawal because of serious protocol violation on the part of the therapist (n= 1; after session 9) related to insertion of CGT into the IPT session.

Secondary Analyses

We found no statistically significant differences in response based on race, age, sex, time since the loss, or relationship to the deceased. Patients taking antidepressant medication had marginally better response rates: for CGT, 13 of 22 (59% [95% CI, 38%-80%]) vs 11 of 26 (42% [95% CI, 23%-61%]) not taking antidepressant medication and for IPT, 8 of 20 (40% [95% CI, 19%-61%]) vs 5 of 26 (19% [95% CI, 4%-34%]) not taking antidepressant medication. Patients who lost a loved one through violent death (suicide, homicide, or accident) had a 56% (95% CI, 32%-80%) response rate with CGT and 13% (95% CI, 0%-30%) response rate with IPT, while for natural, nonaccidental death, there was a 47% (95% CI, 30%-64%) response to CGT and 35% (95% CI, 18%-52%) response to IPT. Parents who lost a child had a low response rate to CGT (17% [95% CI, 0%-52%]) compared with those who lost a spouse, parent, or other friend or relative (average, 60%), while this was not true for IPT, for which the response rate (28%) did not differ by type of loss. While provocative, none of these comparisons was statistically significant.

COMMENT

This randomized controlled trial showed better response to CGT than to IPT, with a number needed to treat of 4.3. Since this is the first such study in this chronically ill population, this result is encouraging. Nevertheless, only 51% responded to CGT, and it is clear that more work is needed. In other studies,20 antidepressant medication alone has shown small changes in complicated grief symptoms. However, patients taking antidepressant medication prior to starting this study did have a marginally better outcome than those not taking medication. Systematic study of combined medication and psychotherapy is needed.

Participants in our study spanned the adult age range and included individuals who lost parents, spouses, children, other relatives, or close friends through violent (33%) or natural (66%) deaths; 22% of participants were African American and 40% were older than 50 years. The heterogeneity of the sample provides further evidence that complicated grief, like most DSM-IV disorders, can be identified in different adult populations and in different psychosocial contexts.

This study has several important limitations. Forty-five percent of study participants were taking psychotropic medications. We considered it necessary to permit continued use of medication for co-occurring DSM-IV Axis I disorders for which CGT, and sometimes IPT, had not been studied. We believed we would unnecessarily limit the generalizability of our findings if we excluded such patients. There was no difference in the rate of medication use in CGT vs IPT. There was a marginally significant effect of medication on outcome, which was more pronounced for IPT (2.1 times the response rate of those not taking medication) than CGT (1.4 times the response of those not taking medication.) A similar proportion of patients taking concurrent antidepressant medication responded to IPT (40%) as those who responded to CGT without medication (42%).

Heterogeneity is another potential limitation. It is possible that subgroups might respond differently to different treatment approaches. We had no prior hypotheses regarding these variables; however, we had insufficient power to detect differences. For example, we observed that patients experiencing violent loss had a very low response to IPT (13%). On the other hand, parents who lost a child showed a much lower rate of response to CGT than patients with other losses (17% vs 60%). Our study was not large enough to have confidence in these observations; thus, they should be considered preliminary. Our conclusions are also limited by the 26% dropout rate from both treatments and the additional 10% who refused to undergo key CGT procedures.

Intervention studies for bereaved individuals often recruited participants without regard to symptom status and used supportive interventions.46,47 A recent meta-analysis of bereavement support interventions showed an effect size of 0.15.48 However, 2 earlier studies49,50 examined efficacy of an exposure-based treatment for individuals considered to have pathological grief and showed significant treatment effects on measures of anxiety and depression. There was no measure of complicated grief in these studies.

Our treatment is the first to target complicated grief symptoms directly. The dual-process model of coping of Stroebe and Schut29 forms the frame- work for our approach. Complicated grief treatment is implemented using loss-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques and restoration- focused IPT strategies. Cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques include repeated retelling of the story of the death and work on confronting avoided situations. Cognitive techniques include an imaginal conversation with the deceased and work on memories. Interpersonal psychotherapy techniques enhance rapport building, assistance in restoring effective interpersonal functioning, and guided treatment termination.

In summary, we conducted the first randomized controlled trial of therapy targeting symptoms of complicated grief. We found better response to CGT compared with IPT, which is a proven efficacious psychotherapy for depression. Similarity of ICG scores across age, cultural, and death-related variables supports the diagnostic validity of the syndrome. Our treatment findings suggest that complicated grief is a specific condition in need of a specific treatment. More research is needed to confirm our findings, to test potential moderators of treatment response, and to improve treatment acceptance.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals, without whose assistance this project would not have been possible: Krissa Caroff, BS (study coordinator); Jacqueline Fury, BS (study research associate); Russell Silowash, BS (data manger); Mary Herschk (study administrative assistant); Rose Zingrone, LCSW, and Randi Taylor, PhD (independent evaluators); Andrea Fagiolini, MD (study pharmacotherapist); Bonnie Gorscak, PhD (CGT backup supervisor); Allan Zuckoff, PhD (study psychotherapist and trainer in motivational enhancement therapy); Daniel Ford, MD, Wayne Katon, MD, and Sidney Zisook, MD (data and safety monitoring board consultants); and David J. Kupfer, MD, Edna Foa, PhD, Holly Prigerson, PhD, and Camille Wortman, PhD (consultants).

Financial Disclosures: Dr Shear has received financial support from Pfizer and Forest Pharmaceuticals. Dr Frank has received financial support from Pfizer, Pfizer Italia, Eli Lilly, Forest Research Institute, and the Pittsburgh Foundation.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants R01MH60783, P30MH30915, and P30MH52247 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Shear and Ms Houck had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Shear, Frank.

Acquisition of data: Shear, Frank.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Shear, Frank, Houck, Reynolds.

Drafting of the manuscript: Shear, Houck.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Shear, Frank, Reynolds.

Statistical analysis: Shear, Frank, Houck, Reynolds.

Obtained funding: Shear.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Shear, Houck.

Study supervision: Shear, Frank.

Role of the Sponsor: The NIMH had no direct input into the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prigerson HG, Jacobs SC. Caring for bereaved patients: “all the doctors just suddenly go”. JAMA. 2001;286:1369–1376. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton PJ, Halikas JA, Maurice WL. The depression of widowhood. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120:71–77. doi: 10.1192/bjp.120.554.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs SC. Measures of the psychological distress of bereavement. In: Zisook S, editor. Biopsychosocial Aspects of Bereavement. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1987. pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, et al. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horowitz MJ, Siegel B, Holen A, Bonanno GA, Milbrath C, Stinson CH. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:904–910. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, et al. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: a rationale and preliminary empirical test. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zisook S, Shuchter SR, Pedrelli P, et al. Acute, open trial of bupropion SR therapy in bereavement. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:227–230. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds CF, Miller MD, Pasternak RE, et al. Treatment of bereavement-related major depressive episodes in later life: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled study of acute and continuation treatment with nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:202–208. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs S, et al. Grief and its relation to posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Nutt D, Davidson JR, Zohar J, editors. Posttraumatic Stress Disorders: Diagnosis, Management and Treatment. New York, NY: Martin Dunitz Publishers; 2000. pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prigerson HG, Frank E, Kasl SV, et al. Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:22–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, et al. Complicated grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement- related depression and anxiety: a replication study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1484–1486. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melhem NM. Traumatic grief among adolescents exposed to their peer’s suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1411–1416. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman GK, Jacobs SC, Kasl SV, Maciejewski PK, Noaghiul FS, Prigerson HG. Quality of life impairments associated with diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Psychol Med. 2000;30:857–862. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, et al. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:616–623. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JH, Bierhals AJ, Prigerson HG, et al. Gender differences in the effects of bereavement-related psychological distress on health outcomes. Psychol Med. 1999;29:367–380. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ott CH. The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Stud. 2003;27:249–272. doi: 10.1080/07481180302887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Middleton W, Burnett P, Raphael B, Martinek N. The bereavement response: a cluster analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:167–171. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs SC. Pathologic Grief: Maladaptation to Loss. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. Births, marriages, divorces and deaths. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr52/nvsr52_22.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2005.

- 20.Zygmont M, Prigerson HG, Houck PR, et al. A post hoc comparison of paroxetine and nortriptyline for symptoms of traumatic grief. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:241–245. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shear MK, Frank E, Foa EB, et al. Traumatic grief treatment: a pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1506–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville B, Chevron ES. Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ablon JS, Jones EE. Validity of controlled clinical trials of psychotherapy: findings from the NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:775–783. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank E, Swartz HA, Kupfer DJ. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: managing the chaos of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:593–604. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cyranowski J, Frank E, Shear MK, Swartz HA, Fagiolin A, Scott J. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression with panic spectrum features (IPT-PS): a pilot study. Depress Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.20069. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank E. Interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent depression. Psychotherapy. 1991;28:259–266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Spanier CA, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy and antidepressant medication: evaluation of a sequential treatment strategy in women with recurrent major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23:197–224. doi: 10.1080/074811899201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hembree EA, Foa EB, Dorfan NM, Street GP, Kowalski J, Tu X. Do patients drop out prematurely from exposure therapy for PTSD? J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:555–562. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000004078.93012.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the Trauma of Rape: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller WR, Rollnick R. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guy W. Clinical Global Impressions: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 34.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton anxiety rating scale (SIGH-A) Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The work and social adjustment scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Revised Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, Tex: Psychological Corp; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chatellier G, Zapletal E, Lemaitre D, Menard J, DeGoulet P. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful nomogram in its proper context. BMJ. 1996;312:426–429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7028.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breslow N, Day N. Statistical methods in cancer research, volume I: the analysis of case-control studies. IARC Sci Publ. 198032:5–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yonkers KA, Samson J. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Mood disorder measures; p. 527. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kearns NP, Cruickshank CA, McGuigan KJ, Riley SA, Shaw SP, Snaith RP. A comparison of depression rating scales. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:45–49. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shear MK, Feske U, Brown C, Clark D, Mammen O, Scotti J. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Anxiety disorders measures; p. 555. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobak KA, Reynolds WM, Greist JH. Development and validation of a computer-administered version of the Hamilton Rating Scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5:487–492. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Windholz MJ, Marmar CR, Horowitz MJ. A review of the research on conjugal bereavement: impact on health and efficacy of intervention. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26:433–447. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(85)90080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marmar CR, Horowitz MJ, Weiss DS, Wilner NR, Kaltreider NB. A controlled trial of brief psychotherapy and mutual-help group treatment of conjugal bereavement. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:203–209. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jordan JR, Neimeyer RA. Does grief counseling work? Death Stud. 2003;27:765–786. doi: 10.1080/713842360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mawson D, Marks IM, Ramm L, Stern RS. Guided mourning for morbid grief: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:185–193. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramsay RW. Behavioural approaches to bereavement. Behav Res Ther. 1977;15:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(77)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]