Abstract

Medication adherence among youth living with HIV (28%–69%) is often insufficient for viral suppression. The psychosocial context of adherence barriers is complex. We sought to qualitatively understand adherence barriers among behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth and develop an intervention specific to their needs. We conducted in-depth interviews with 30 youth living with HIV (aged 14–24 years) and analyzed transcripts using the constant comparative method. Barriers were influenced by clinical and psychosocial factors. Perinatally infected youth barriers included reactance, complicated regimens, HIV fatigue, and difficulty transitioning to autonomous care. Behaviorally infected youth barriers included HIV-related shame and difficulty initiating medication. Both groups reported low risk perception, medication as a reminder of HIV, and nondisclosure, but described different contexts to these common barriers. Common and unique barriers emerged for behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth reflecting varying HIV experiences and psychosocial contexts. We developed a customizable intervention addressing identified barriers and their psychosocial antecedents.

Keywords: HIV, medication adherence, adolescent, young adult, antiretroviral therapy, psychosocial context, grounded theory, semi-structured interviews, New England

Introduction

Youth account for a significant number of HIV cases in the United States. An estimated 9,961 youth were diagnosed with HIV in 2013, representing 21% of the 47,352 people diagnosed that year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2015) and an estimated 10,000 perinatally infected children are aging into adolescence and young adulthood (Hazra, Siberry, & Mofenson, 2010). HIV-associated morbidity and mortality have declined significantly since the initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, only an estimated 6% of youth living with HIV have achieved the viral suppression necessary to avoid HIV-associated morbidity and mortality (Zanoni & Mayer, 2014). Recent studies suggest the adherence threshold to achieve viral suppression ranges from 80% to 85% to >95% (Bangsberg, 2006; Bezabhe, Chalmers, Bereznicki, & Peterson, 2016; Chesney, 2003; Shuter, Sarlo, Kanmaz, Rode, & Zingman, 2007; Thompson et al., 2010); however, higher levels of adherence (>95%) are associated with improved clinical and immunologic outcomes (Hart et al., 2010). Yet, ART adherence among HIV-infected youth ranges from 28% to 69% of doses prescribed (Naar-King et al., 2006; Reisner et al., 2009) and only 62.3% (95% confidence interval = [57.1, 67.6]) have optimal adherence to ART based on a meta-analysis of 50 adolescent and young adult HIV studies (Kim, Gerver, Fidler, & Ward, 2014).

Studies exploring ART adherence behavior among adolescents and young adults have identified several barriers, including high pill burden/complex or difficult medical regimen, severity of HIV disease (Chandwani et al., 2012), forgetfulness (Buchanan et al., 2012; Chandwani et al., 2012), low perceived need for medication, poor motivation (MacDonell, Naar-King, Huszti, & Belzer, 2013), lack of social support, unstructured lifestyles, access to health care (Hosek, Harper, & Domanico, 2005; Rudy, Murphy, Harris, Muenz, & Ellen, 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2013; Wiener, Kohrt, Battles, & Pao, 2011; Williams et al., 2006), mental health disturbances (Rudy et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2006), stressors related to disclosure of status (Orban et al., 2010), and medication as a reminder of HIV status (MacDonell et al., 2013). Adolescents and young adults may also have difficulty managing medication responsibilities and a chronic, stigmatizing disease in the context of developmentally appropriate behavioral experimentation, needs for autonomy, risk taking, identity formation, and evolving decisional capacity (Arnett, 2004; Battles & Wiener, 2002; DeLaMora, Aledort, & Stavola, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2013).

While these barriers to adherence have been reported in studies of both behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth, these youth may also have unique barriers based on distinct clinical needs, differences in lived experience with HIV and psychosocial contexts and differences in treatment experience and duration. Perinatally infected youth are generally heavily ART-experienced and at greater risk for drug resistance than behaviorally infected youth (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2013), leading to salvage therapy involving heavy pill burden and complex dosing instructions (Hazra et al., 2010). Rebellion against medication adherence and treatment fatigue may be more prominent among perinatally infected youth as compared with behaviorally infected youth (Merzel, Vandevanter, & Irvine, 2008; Spiegel & Futterman, 2009). Availability of social support and stress-ors related to disclosure may also vary between behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth. Although perinatally infected youth may have complex unresolved issues with caregivers related to delayed disclosure of their diagnosis (Spiegel & Futterman, 2009), they are more likely than behaviorally infected youth to have familial social support (Chandwani et al., 2012). Conversely, behaviorally infected youth may experience stigma associated with HIV-related risk behaviors and are often required, shortly after diagnosis, to make immediate decisions regarding to whom they should disclose their status and from whom they should seek social support (Spiegel & Futterman, 2009). The majority of behaviorally infected youth are also sexual minority youth, primarily young men who have sex with men (CDC, 2015), yet few qualitative papers have focused on barriers to adherence in this population. One study on HIV treatment engagement among gay and bisexual adolescent males showed that young men with more negative attitudes toward gay and bisexual persons were more likely to miss a recent HIV appointment, a finding the authors felt could be attributed to internalized homophobia (Harper, Fernandez, Bruce, Hosek, & Jacobs, 2013).

These studies suggest barriers to adherence among adolescents and young adults are multifaceted and specific to the varying experiences of behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth. Like other health behaviors, adherence is also affected by one’s social ecology where behavior is influenced at multiple levels (e.g., macro, exo, meso, micro, and the intrapersonal/individual levels; Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008). To be effective, interventions for improving adherence behavior in this population must also be multifaceted, specific to the needs of youth being targeted, and mindful of the social ecology influencing this behavior. Many interventions for youth have focused on individual barriers such as pill swallowing (Garvie, Lensing, & Rai, 2007) or forgetting doses (Dowshen, Kuhns, Johnson, Holoyda, & Garofalo, 2012) and few have focused specifically on the differences identified between behavior-ally infected and perinatally infected youth or specifically catered to the different needs of these two groups. Thurston et al. (2014) describe a multifaceted, customizable adherence intervention for adolescents and young adults based on an adult evidence-based intervention (Safren, Otto, & Worth, 1999); the present manuscript describes the semistructured qualitative interviews with behaviorally and perinatally infected youth that informed the development of that intervention.

Qualitative research methods have gained widespread interest in the movement toward patient-centered care as they elicit deeper insights into participant’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (Tong, Palmer, Craig, & Strippoli, 2014). Researchers across numerous fields have used these methods to develop clinical interventions including nursing (Miller, 2010), occupational therapy (Hammell, 2001), and school-based health (Gittelsohn et al., 2006). These methods serve as a powerful tool in the design and implementation of clinical interventions by allowing the researchers to develop a deep understanding of the psychosocial factors affecting the target population. These insights allow health professionals to better tailor interventions to enhance relevance, participant investment, and sustainability (Yardley, Morrison, Bradbury, & Muller, 2015). Qualitative methods have gained significant importance, particularly in the role of combating sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV by enabling researchers to better capture the complex dynamics of health behaviors involved in transmission and treatment (Power, 2002). Barriers to adherence are particularly complex and qualitative research offers a unique method of understanding the complex cognitive, social, cultural, and structural factors that affect adherence (Gittelsohn et al., 2006).

We sought to expand the existing research on adherence barriers among behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth by exploring the psychosocial context of these barriers through semistructured qualitative interviews and highlighting the utility of qualitative research for clinical care by using study findings to design an intervention specific to the varied needs of these youth. We felt the psychosocial context of these barriers would provide a deeper understanding of the unique challenges faced by behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth, and inform strategies to help youth address these barriers. Using qualitative inquiry, we explored narratives of experience with ART among HIV-infected youth to identify (a) common and unique barriers to medication adherence among behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth and (b) the psychosocial context of these barriers and how common barriers affected each group uniquely.

Method

Study Population and Design

Using semistructured qualitative interviews with behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth we explored, compared, and contrasted the psychosocial context of medication adherence in the two groups. We used a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) in sampling, participant interviews, and analysis of these interviews to develop a theory to understand differences in barriers to adherence between behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth.

Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

Participants were recruited during visits at a hospital-based clinic and an urban community health center in a major New England city in the fall of 2010. Clinics were selected that cared for behaviorally infected youth, perinatally infected youth, or both to ensure comparable numbers of youth from both groups were recruited. We conducted preliminary thematic analyses throughout data collection to assess new themes, nominated sampling to identify individuals representative of the range of adherence behaviors and challenges observed in these patient populations, and theoretic sampling to select participants with specific characteristics to further clarify emerging ideas. Nominated sampling is a sampling strategy that improves transferability of the findings by identifying participants that represent the phenomenon being studied (Krefting, 1991; Morse, 1990). We worked with clinicians in the abovementioned clinic settings to nominate potential participants. Theoretic sampling is an iterative sampling strategy central to grounded theory that allows investigators to select settings, people, or events that may further the development of emerging theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Sampling and data collection continued until data saturation was reached (i.e., no new themes emerged). Inclusion criteria were (a) age 13 to 24 years, (b) HIV-infected, (c) currently recommended or prescribed ART by their HIV provider, and (d) aware of HIV status. Prior to semistructured interviews, participants completed a brief questionnaire about demographic characteristics, health status, mode of HIV infection, and medication adherence. Medication adherence was measured using standard survey items assessing the percentage of doses taken in last month (Simoni et al., 2006). Participants were also administered the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). If participants screened positive for depression, they were referred to the study mental health clinician who assessed for safety and provided participants with mental health referrals, but were not excluded from the study. The qualitative interviews lasted 45 to 90 minutes and were conducted by master’s and bachelor’s–level research assistants trained in conducting semistructured research interviews. Participants received a US$30 incentive and transportation reimbursement. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by research staff.

Data collection procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Fenway Health and Boston Children’s Hospital. Eligible participants older than 18 years provided written informed consent prior to entering the study. Participants younger than 18 years provided informed assent and their parent/guardian provided written informed consent.

Qualitative Interview Protocol

The interview protocols were developed based on previously published data and investigators’ past work on barriers to HIV care (Bogart et al., 2012). The interview instrument included questions relevant to participants’ treatment adherence including their living situation, education/employment, interpersonal relationships, relationship with medical providers, experience with ART, and perceived barriers to adherence.

Qualitative Analysis

We used the constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) of grounded theory to analyze interview data. Using Atlas.ti® (Version 5.2; Berlin, Germany, Muhr & Friese, 2004), a qualitative software package, we conducted categorical analysis to explore barriers to ART adherence in each group of HIV-infected youth. We used a three-stage analytic coding strategy described by Corbin and Strauss (2015) that included open coding (examining transcripts for salient categories or codes), axial coding (identifying relationships between codes), and selective coding (identifying a core category integrating axial codes; see Table 1). Transcripts were fractured into discrete segments, which were sorted into categories and coded, thus facilitating a comparative examination across participants of adherence barriers and facilitators.

Table 1.

Selected Codes From Three-Stage Analytic Coding Process.

| Open Codes | Axial Codes (Categories) |

Selective Coding (Dimensions) |

Core Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological impact of meds/reminder of HIV status | Barriers to adherence | Proximate determinants (barriers and facilitators) of adherence | Unique and common barriers between behaviorally and perinatally infected youth had the most proximate influence on adherence behavior. Psychosocial context influenced behavior further upstream and were shaped by participants’ lived experience with HIV, which differed substantially by mode of transmission. The core category or central theme that emerged from these data is that individual adherence behavior was affected by multiple levels of influence— the psychosocial context of participants’ lived experience with HIV at the meso and micro levels of influence (e.g., family dynamics, HIV stigma, adolescent transitions and development) and, at the intrapersonal level, their reactions to that psychosocial context. |

| Complicated ART regimen | |||

| Fatigue from chronicity of HIV | |||

| Mental health | |||

| Nondisclosure/need for privacy | |||

| Substance use/abuse | |||

| Avoiding health consequences/staying healthy | Adherence strategies/motivations | ||

| Interpersonal reminders | |||

| Protecting partner/child | |||

| Finding out status/dealing with diagnosis | Living with HIV | Psychosocial (upstream) determinants of adherence | |

| Impact of parents HIV | |||

| HIV stigma | |||

| Self-blame | |||

| Stigma associated with sexuality/risk behaviors | |||

| Avoiding reprimand/message fatigue | Reactance | ||

| Challenging/thwarting authority figures | |||

| Family relations | Social support | Interventions to improve adherence in these populations must consider multiple levels of influence proximately and upstream. | |

| Support from others living with HIV | |||

| External motivations for HIV management | Locus of control for HIV adherence and management | ||

| Independent/autonomous HIV management | |||

| Transitions in responsibility for HIV management | |||

| Internal/personal responsibility for HIV management | |||

| Provider relationship and adherence | Impact of social network on adherence | ||

| Parents/family influence on adherence | |||

| Relationship with friends and adherence | |||

| Significant other/romantic relationship and adherence |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Codes related to adherence were identified through open coding and data immersion. Through axial coding, a three-tiered coding hierarchy was developed based on categories that emerged during the open coding process performed by Dr. Errol Fields. Dr. Fields then developed a codebook with codes organized according to this hierarchy and trained two members of the research staff on the completed codebook. We used stepwise replication (Guba & Lincoln, 1989; Morse, 2015) to improve the dependability of the coding process. These two coders double-coded 20% of the transcripts to establish interrater reliability based on the following axial codes/categories that emerged from the analysis: barriers, facilitators, reactance, living with HIV, impact of interpersonal relationships, locus of control for HIV adherence, social support, and disclosure. Cohen’s kappa, indicated excellent consistency (>0.80) between coders on all categories according to the conventions on the use of kappa for interrater agreement (Cohen, 1960). Differences in coding were discussed between Dr. Fields and the two additional coders until a consensus was reached. After establishing agreement, the two coders completed the remaining transcripts.

For selective coding, the final stage of coding, we focused on developing a theoretical framework through identification of a core category/theme. This was accomplished through “storytelling memos” written throughout the two prior stages of the coding process that contained emerging research questions, recurring themes, and hypotheses about reasons for variation within and across participants.

Qualitative Rigor and Trustworthiness

To ensure qualitative rigor, we used several strategies to improve the four qualitative criteria for trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. We have summarized these strategies in Supplementary Table 1. We structured the interview guide and the interview techniques to enhance credibility (Krefting, 1991). We used the nominated sample strategy to improve transferability as described above. To improve the dependability of the findings, we used stepwise replication in the coding process (described above) and peer examination (Guba & Lincoln, 1989; Krefting, 1991; Morse, 2015; by team members not directly involved in data collection or analysis of the findings) at different stages in the data collection process. Finally, to improve confirmability, we used a team of researchers familiar with qualitative methods rather than a single researcher to improve the neutrality of data and interpretational confirmability (Krefting, 1991).

Results

Participant Demographic, Medication, and Adherence Characteristics

Thirty HIV-infected youth aged 14 to 24 years (M = 20 years, SD = 2.7) participated in the study. Forty percent of these youth were behaviorally infected (N = 12) and 60% were perinatally infected (N = 18). The sample was diverse with respect to race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation (see Supplementary Table 2). Sixty-seven percent of behaviorally infected youth and 83% of perinatally infected youth were taking ART at the time of the study. Of those on medication, 50% of behaviorally infected youth and 40% of perinatally infected youth reported adherence less than 85% (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Medication and Adherence Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Perinatally Infected

|

Behaviorally Infected

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| ART | ||||

| Currently taking ART | 15 | 83 | 8 | 67 |

| Years on ART | ||||

| 0–1 | — | — | 7 | 58 |

| 1–2 | — | — | 1 | 8 |

| 2–5 | — | — | — | — |

| 5+ | 15 | 83 | — | — |

| Adherence | ||||

| >85% | 9 | 60 | 4 | 50 |

| <85% | 6 | 40 | 4 | 50 |

Qualitative Findings

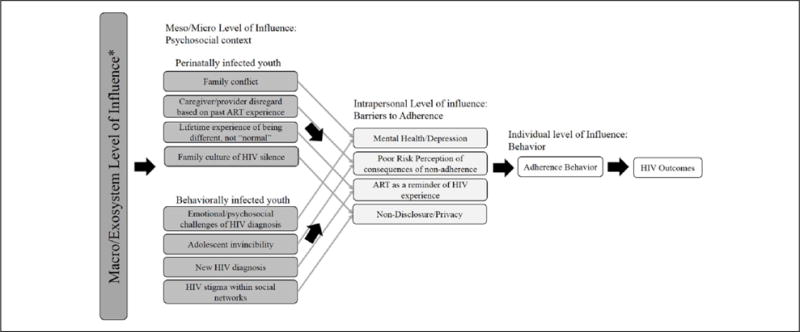

In this study, behaviorally and perinatally infected youth described unique and common barriers to adherence. These barriers had the most proximate influence on adherence behavior. Psychosocial context influenced behavior further upstream and were shaped by participants’ lived experience with HIV, which differed substantially by mode of transmission. The core category or central theme that emerged from these data is that individual adherence behavior was affected by multiple levels of influence— the psychosocial context of participants’ lived experience with HIV at the meso and micro levels of influence (e.g., family dynamics, HIV stigma, adolescent transitions, and development) and at the intrapersonal level, the barriers resulting from the influence of the psychosocial context. We developed a theoretical framework based on these findings and derived from a social ecological framework (see Figure 1; Bronfenbrenner, 1986). Psychosocial context varied between perinatally and behaviorally infected youth by nature of their different experiences with HIV such that even common barriers to adherence had very different antecedents. We used barriers common to both groups in Figure 1 as examples to illustrate the distinct psychosocial contexts influencing these barriers across groups. For example, nondisclosure of HIV status was described as an adherence barrier in both groups; however, in behaviorally infected youth, the psychosocial contextual antecedent to this barrier was HIV stigma within social networks. Among perinatally infected youth, nondisclosure was influenced by a culture of HIV silence within their families.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the psychosocial context of adherence barriers and behavior.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Barriers common to both groups

Overview

Behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth described several common barriers to medication adherence including substance use, medication side effects, and unstructured lifestyles. Behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth described the psychosocial contexts of these barriers similarly. For instance, substance use was reported as a barrier in both groups because use of substances would increase their likelihood of forgetting a dose. Aversion to or the experience of side effects led to medication avoidance in both groups. Remembering medications was difficult in both groups in the context of the unstructured lifestyles typical of adolescence and young adulthood (e.g., balancing school and work, college lifestyle, late night social outings, etc.).

Both groups also described depression and other mental health challenges, poor risk perception of consequences of nonadherence, medication as a reminder of HIV, and privacy/nondisclosure of HIV status. The psychosocial context of these barriers, however, was described differently by behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth.

Mental health

Both groups described depressed mood was a common barrier and described a similar mechanism through which depressed mood could affect medication adherence, for example, by leading to low motivation such that one does not want to “do anything … don’t want to go to work … don’t want to take my medicine” (Behaviorally infected male). Both groups also described depressed mood leading to forgetfulness and decreased attention to treatment regimens. One young man felt depression affected his “willingness to stay invested in it [treatment and ART]” but when “there’s not as much emotional turbulence, then it’s easier to stick to a schedule” (Behaviorally infected male). Both groups discussed ways depression led to apathy and fatalism. As one young woman described,

When I’m depressed, I don’t want to deal with it. I don’t want to deal with HIV. I couldn’t care less about living honestly … So, it didn’t mean anything for me to take my medications, it’s like if I, if I die, I die. (Perinatally infected female)

Although the experience of depression and its effect on adherence was similar for behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth, there were contextual differences in the source of mood disturbances. Perinatally infected youth more often described emotional disturbances within their families, including the death of a parent with HIV or poor family interactions:

My mother passed away in 2002 [from HIV] and I had never fully dealt with it … so that was a big issue … and then I was aggravated by these foster parents and my aunt who I was also living with [and] I was under the impression that everyone was trying to take my mother’s place … so I was really trying to deal with a lot of those things … so like the denialism that came along with it … just not wanting to know or care or remember … so most of the time I just didn’t take them. (Perinatally infected female)

Behaviorally infected youth more often described emotional and psychosocial challenges with adjusting to their new HIV diagnosis and its impact on their lives:

If you’re depressed, you wouldn’t want to take the med because that’s just going to make you more depressed. Like every time I take my med, I honestly feel depressed ‘cause I really forget that I have HIV for most of the day ‘til I go to take my med and then [it’s] like, yeah, reality check. (Behaviorally infected male)

I was very angry at HIV. I was very angry. Because I was missing chunks of my son’s life and other people were taking care of him and I felt burdened or I felt like I was a burden to other people that they were having to take on my job as a parent to him. And, um, my fiancé was working. So definitely, I was depressed, I was angry. If it wasn’t for the nurses handing me the medication when I was supposed to take it, I wouldn’t have taken it. (Behaviorally infected transgender male)

Risk perceptions

For both groups, poor risk perception of the long-term consequences of nonadherence manifested as inattention to these consequences and prioritizing immediate emotions or other motivations above taking medication. Perinatally infected youth risk perceptions were based on prior experience with nonadherence and the lack of any negative consequences in the short term (illness, rising viral load, etc.):

I’ve always done really well without them. So that was part of the reason why I stopped taking them … why should I if I’m doing fine without them … physically and my viral load and my CD4 count would always be pretty good. Like being on them I guess my viral load would be lower or something, but it wasn’t a great difference if I was on or off. (Perinatally infected female)

Some also described a fear of death ingrained in them as children if they did not take their medication. Realizing this was not true in the short term, bolstered these justifications for nonadherence:

I mean when you’re young I used to think if I missed two doses in a row I am just going to die … as you get older you realize the truth … you know you’re not going to like get sick or die the next day. (Perinatally infected male)

Risk perceptions of behaviorally infected youth, who were typically less treatment-experienced, were reflected in descriptions of their general invincibility as justifications for nonadherence:

Some days I get—what do you call it—Clark Kent in my head and I think I’m just Superman. And I was just like, you know, I don’t really need this. (Behaviorally infected male)

Reminder of HIV

ART was a reminder of HIV status for both groups. The differences in this barrier between behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth reflected the different role HIV status played in their lives. For perinatally infected youth, taking medication was a reminder they were different from their friends and family members. Many described it as a reminder they were “not normal.”

It’s kind of hard ‘cause every day waking up, taking medicine, it is hard. You know … every day seeing other people how they live normal lives and you want to live that normal life and you can’t. (Perinatally infected male)

For perinatally infected youth, medication had been a reminder of having always been different dating back to early childhood. One youth’s description of her daily routine of going to the school nurse’s office for her medications is an illustration of this point:

It was very different for me because I used to have a G-tube to help me take my meds. It was harder for me ‘cause I have to take my meds at school, so I would go to the nurse’s office and I would have to keep the medicines in my backpack traveling back and forth. (Perinatally infected female)

For behaviorally infected youth, starting and adhering to ART was a reminder of HIV as a new diagnosis to which many had not yet adjusted. As one young man described, before being told he needed to start medication, his HIV status had not affected him because he “wasn’t like accepting the fact that I have HIV” (Behaviorally infected male). Similarly, the prospect of taking medication, for some, also triggered the negative emotions associated with being diagnosed with HIV or becoming infected. One newly infected young transgender man initially avoided ART because he did not want to think about being HIV-positive:

I think for me it’s been more of an emotional thing. It kind of reminds you every day of something you’d like to not think about. (Behaviorally infected transgender male)

Nondisclosure/privacy

Both groups of participants also expressed discomfort with disclosing and a desire for privacy about their HIV status, which led to delaying or skipping doses so others would not see them taking or carrying medication. Both groups tried to avoid the stigma associated with HIV, but there were different dynamics in each group surrounding HIV stigma. Behaviorally infected youth described HIV stigma within their social networks and for some avoiding this stigma affected their adherence behavior:

I’ve been very fortunate in that the people that I’ve made friends with have been very caring, but I think the gay community is very judgmental and although it’s not the death sentence that it used to be, it’s still a very big stigma. (Behaviorally infected male)

In the beginning, I had a pharmacy around the corner from my mother’s house and I had it transferred there, so I could get it that same day. When I went to go pick it up I found out that my ex’s best friend was the pharmacist. So I called my um social worker and I told her I didn’t want to get it, and she switched me over here, which is still another problem because I know so many people who are here. I think keepin’ it a secret is difficult. (Behaviorally infected male)

Perinatally infected youth described similar concerns, but many also described a familial culture of silence around their HIV status that prohibited them from disclosing their status outside of their families or (for some) discussing their status among family members. One young woman had some support from her mother who was living with HIV, but her father’s silence around HIV and his insistence on secrecy limited other sources of social support for adherence:

My father didn’t want people knowing about my status, so it was better to just keep it hidden … we never really had any conversations about [HIV], not until recently, but for all the years growing up … we never talked about it. It was basically just take your medication and don’t talk about it. (Perinatally infected female)

Barriers specific to perinatally infected youth

The barriers to adherence unique to perinatally infected youth reflected their longer, often lifelong experience with ART. These barriers included reactance (i.e., opposition to authority figures), complicated ART regimens, fatigue from chro-nicity of HIV, and challenges with transitions to independent HIV care.

For many of the perinatally infected youth, taking ART was a point of conflict with their caregivers and medical providers. Perinatally infected youth often described nonadherence as a means of exerting control and independence from caregivers:

It’s like “take it, take it, take it.” And it’s like “OoooK like shut up” you just take it because someone’s telling you to take, it’s not because you want to take it’s because you want to shut them up. I think that creates a factor in people and that’s why when they grow and they become independent they’re like “Fuck this shit ain’t no one going to tell me when to take it so I am not going to take it.” (Perinatally infected female)

Many described not wanting to be told to take their medication and would respond by refusing to take them. For these participants, not taking their medication was a manner of “retaliating” against being told what to do, especially in the context of an argument:

[My aunt] was like, a main cause of me not taking my medicine. Her and her kids. They would scream at me. Like, if you scream at me that’s not gonna make anything better. It’s just gonna make it worse … And then she’s, she’s just like “no attitude” like, how do you expect me not to give attitude but you give me an attitude? Obviously I’m gonna give it back. I’m not a wall. I’m not gonna just let you throw stuff at me and not expect [me] to retaliate. (Perinatally infected female)

Participants commonly described arguing and being reprimanded by caregivers and medical providers. In this context, the perception of being “disrespected” or “annoyed” by requests to take one’s medication was often cited as the reason for participants’ refusal to take medication:

If someone is really, if someone is struggling taking their meds, annoying them is just pushing them away from taking their meds … at least with me personally. ‘Cause if someone annoy me, if someone’s watching me every 5 seconds to make sure I take my meds, I’m just not gonna to do it. I’ll tell you I’m doing it, but I’m not going to do it. (Behaviorally infected male)

Perinatally infected youth also described regimens with heavy pill burden or multiple times a day dosing as barriers:

I had 10 pills I had to take. And it was hard for me to take them. In a day I would take them and I would make myself throw it back up. Just to tell them “oh I can’t take this type of medicine. Give me something else.” (Perinatally infected male)

Many, having benefited from the recent development of once daily or one pill once daily regimens, described these as historical barriers but felt they would do poorly if they had to return to these more complicated regimens:

When I was like seven, I had to take like five or eight pills, uhh, I couldn’t do it. It was too much, and sometimes the pills are thick, uhh, I could not do it … yeah, that was bad. Yeah, it was harder to take, and some of the pills made me sick, it was too much. Now it’s better … back in the day it was terrible. (Perinatally infected male)

These more complex regimens were also taken during a time when participants were younger and their caregivers played a larger role in their medication adherence:

I’d have to take this, that, 2 white ones, a Bactrim and then like 2 more. And it was just like, a lot of pills. They were like horse pills, so I never liked those. I missed a few because they were so much. Like, it was 10 pills going in my throat. I didn’t like that. So I would take those and then my mom would like, tell me to take it again or like take it tomorrow. And if you forget, no ice cream or something. (Perinatally infected female)

In addition, complicated regimens made adherence more difficult in social settings where participants otherwise wished to keep their status undisclosed:

When I did take the 4 morning, 3 night … I would be so scared in front of [my friends]. And if we had like, a party with more than one person, then I’d feel awkward. Because I don’t feel like explaining myself to everybody. (Perinatally infected female)

Despite often having easier regimens than in early childhood, many of the perinatally infected youth discussed medication fatigue as a barrier to adherence. For some, this fatigue emerged from the physical act of taking medications daily:

It’s like, you been taking it so much that your body’s getting sick of it, but you need to. It’s like you be eatin’ the same food and you’re tired of it. That’s how your body reacts. You don’t want to do it, but you have to. It’s been too long and it’s sickening, it’s disgusting and no matter how you put it. ‘Cause, it’s just pills after pills after pills, it’s like you eatin’ like the same food every day for your whole life, you get aggravated … you get sick of it. (Perinatally infected male)

Others seem to grow tired of the prospect of daily, lifetime medication. As one young man described,

It’s kind of hard ‘cause every day waking up, taking medicine, it is hard … Sometimes I don’t know sometimes I just like … sometimes I feel like not doing none of this stuff you know. ‘Cause it’s tiring. (Perinatally infected male).

Some cited this fatigue and/or frustration as a reason for skipping a dose or being nonadherent in general:

One of the big issues that we deal with is just not wanting to, ‘cause it gets tiring having to take such big cocktails. (Perinatally infected female)

Because many of the perinatally infected youth had been on medication and in treatment their entire lives, they also faced the unique challenge of transitioning the responsibility of their care from their parents and guardians to themselves. For some of the perinatally infected youth, this transition period was marked by poor treatment engagement and medication nonadherence:

I always took them at a younger age … my grandmother would have the pills in the pill box … [and] remind me to take them. Then as it became routine, that, “no, I don’t want to take them,” or “yeah, I did [take them],” but I really didn’t take thing, that’s when I began to get like really sick and I spent like a lot of time in the hospital. (Perinatally infected female)

Some were not prepared for this responsibility and were not yet capable or willing to independently manage their care. As one young woman described,

My parents would bring them to my school and have me take them. But, one time, my parents tried to have me bring them myself. But, I was in gym class and they fell out of my pocket and sooo … yeah, [laughs] that kind of ended that. (21-year-old perinatally infected female)

Others, now tasked with making these decisions on their own, chose not to take their medications or engage in care:

Me personally, honestly, I just don’t go [to my medical appointments]. I get lazy, and it all depends, if I am not getting a ride, I am not going. (Perinatally infected male)

Barriers specific to behaviorally infected youth

The barriers for behaviorally infected youth reflected their response to being newly diagnosed with HIV and the stigma associated with HIV and transmission-related risk behaviors. Participants described self-blame (i.e., internalized stigma) for infection and the need for emotional readiness to initiate ART.

Among some of the behaviorally infected youth, the stigma associated with HIV and the behaviors that put one at risk for infection manifested as shame and personal culpability for their infection. One young man blamed himself for his HIV infection that occurred in the context of social isolation, depression, and increased sexual risk behavior:

I was pretty depressed … I was down [south] for 3 years, um going to school and I just didn’t seem to make the connections that I did while I was [home] … I didn’t have a very good group of friends … My depression kind of led me to do some things that weren’t really very safe. You know, I was looking for attention, male attention and I kinda just took it when I could get it and didn’t really ask any questions so I think that’s definitely what got me in trouble with HIV. (Behaviorally infected male)

One young transgender woman was so ashamed of her diagnosis she threw away her first bottle of pills after a friend discovered them in her home. She recognized to be adherent she would need to prioritize her treatment and be open with her medication and diagnosis, but was too embarrassed to take that step:

I’m at a place where I don’t want to take medication right now. I’m still embarrassed and ashamed … Somebody will come over and see it sitting out and it’s just like, “fuck” … if I’m gonna take it consistently, if I’m gonna stay on track with it, it needs to be front and center. Not hidden away where people can’t see. (Behaviorally infected transgender female)

Like this young woman, others also discussed delaying ART initiation until they were emotionally ready:

I actually did refuse to get on meds until [earlier] this year. I wasn’t ready to do it. There’s a huge amount of anxiety and I think there’s an element of denial that if you don’t go and get the lab tests done you just can assume that you’re fine … and wanting to sort of ignore it and not being … not ready to deal with the medical aspect of it and not wanting to feel tied to your doctor’s office. (Behaviorally infected transgender male)

While this delay provided an opportunity to address emotional and psychological barriers to treatment, it also created a potential barrier for initiating therapy when it was clinically indicated and recommended by medical providers:

I was asked about going on meds during that first year after diagnosis, during which my T-cells were dropping and they got in the 200s range, but I resisted starting medications … it was something where I started on the medications after feeling … emotionally in a place where I was like, this will be the next step. (Behaviorally infected male)

Discussion

Common and unique barriers emerged for behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth reflecting varying HIV experiences and psychosocial contexts. Barriers to adherence for perinatally infected youth included reactance, complicated ART regimens, fatigue from chronicity of HIV, and challenges with transitions to independent HIV care. Barriers specific to behaviorally infected youth were shame and self-blame about their HIV diagnosis and difficulties with initiating ART when clinically indicated. Barriers to adherence that emerged consistently across behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth were substance abuse, medication side effects, depressed mood and other mental health challenges, unstructured lifestyles, poor risk perception of consequences of nonadherence, medication as a reminder of HIV, and nondisclosure of HIV status. By examining the psychosocial context that contributed to these barriers, we developed a theoretical framework (Figure 1) where individual adherence behavior is affected by multiple levels of influence (as conceptualized in the social ecological framework; Bronfenbrenner, 1986). Psychosocial context varied between perinatally and behaviorally infected youth by nature of their different experiences with HIV such that even common barriers to adherence had very different antecedents.

Our findings of challenges to adherence that were specific to behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth and barriers common to both groups is consistent with prior quantitative research (MacDonell et al., 2013). However, our findings extend prior research by describing differences in the psychosocial context of medication adherence barriers for behaviorally infected versus perinatally infected youth and placing these contexts within a theoretical framework to explain their influence on adherence behavior. Behaviorally infected youth were facing the challenge of adjusting to a new, often highly stigmatized diagnosis while transitioning to adulthood. Perinatally infected youth were challenged with managing HIV during a critical developmental period from childhood to adolescence and into adulthood, transitions that are often disruptive to the management of chronic illness (Holmbeck, 2002). Many perinatally infected youth also had family situations and intrinsic social support that were influenced by having other HIV-infected family members. The effects of these distinct psychosocial contexts were apparent in the different barriers described by behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth and in their different experiences of common barriers. Our framework suggests that strategies to address barriers to adherence must address the psychosocial antecedents to these barriers, which may vary based on one’s lived experience with HIV.

These results illustrate the advantage of using qualitative inquiry to assess barriers to adherence. Although prior quantitative studies have listed and enumerated barriers reported by behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth (Hosek et al., 2005; Merzel et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2001; Rudy et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2006), they have been unable to describe the unique experience of these barriers. Prior qualitative work focused on caregivers and has not captured these experiences directly from HIV-infected youth (MacDonell et al., 2013). We further used the in-depth nature of our findings to inform the design of an intervention that offers unique flexibility and psychosocial insight and acknowledges that distinct psychosocial antecedents of adherence barriers require distinct strategies to intervene and surmount those barriers.

The specifics of this intervention are described in detail elsewhere (Thurston et al., 2014). Briefly, Positive Strategies to Enhance Problem Solving (STEPS), adapted from Life-Steps, an adult intervention (Safren et al., 1999), utilized principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002), and problem solving (D’Zurilla, 1986; Nezu & Perri, 1989) to address adherence barriers unique to behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth. We designed a multifaceted, customizable, five-session one-on-one intervention. The themes identified in this article were used to develop modules for addressing potential barriers with infected youth (sessions focused on barriers directly relevant to the patient’s adherence struggles). Depending on the barrier, these modules incorporated behavioral principles/tools described above to address each patient’s specific difficulty with adherence and the psychosocial context surrounding those difficulties. Findings from this study enabled us to improve customizability, understand participant values and psychosocial stressors, and develop relevant modules for an extremely diverse population.

This study has several limitations. Although the sample was fairly diverse, we were limited by its size and composition. Although our sample was large enough to compare barriers by mode of transmission, it was not large enough to compare themes across different subgroups of behaviorally infected and perinatally infected youth (e.g., younger adolescents, heterosexual or injection drug use [IDU] behaviorally infected youth, etc.). For instance, a notable barrier unique to behaviorally infected youth was shame and personal culpability for infection. Behaviorally infected youth participants attributed this shame to HIV-related risk behaviors. One of these youth, a transgender male, ascribed this shame to his IDU, while others ascribed it to their sexual behavior. The majority of behaviorally infected youth identified as gay or bisexual and there was not enough diversity in the sample nor did it emerge in the interviews whether this shame and personal culpability arose from internalized or external sources of homophobia. Focus groups of different subpopulations may have made these comparisons more readily available. However, focus groups have been described as less appropriate for soliciting personal information from participants compared with in-depth interviews (Powell & Single, 1996). Using this method may have limited the depth of the data—especially youth’s openness to provide personal psychosocial contexts (a significant strength of this study).

Despite effective HIV medication treatments, we know medications do not work unless they are taken properly. However, there are many, often intertwining, physical, emotional, and psychological barriers that are uniquely experienced based on youth’s mode of HIV infection and accordingly need to be continuously addressed by trained personnel to maintain optimal adherence over time. Qualitative research strategies allow clinicians and other public health professionals to develop a deeper understanding of these barriers and directly incorporate these findings into customizable, targeted interventions such as the Positive STEPS program developed by this author group (Thurston et al., 2014). The presence of both common and unique barriers and the distinct psychosocial context influencing these barriers among behaviorally infected versus perinatally infected youth suggest interventions and clinical management strategies are needed to address the common and the distinct barriers to HIV treatment and medication adherence, and their psychosocial antecedents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Madeline Wachman and Laurel Sticklor.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among HIV-Infected Youth Harvard University CFAR Grant (P30 AI060354) and the Center for Collaborative Community Research (NICHHD RC4 HD06690). E. L. Fields was additionally supported by Harvard Medical School, Center of Excellence in Minority Health Disparities, Health Disparities Postgraduate Fellowship, the CHB, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine MCH/HRSA LEAH T71 MC00009, the JHU Leadership Education in Adolescent Health (LEAH) Program (MCH/HRSA LEAH T71MC08054), and the JHU Adolescent Health Promotion Research Training Program (NICHD T32-HD052459). S. A. Safren was additionally supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K24-MH094214).

Biographies

Errol L. Fields is an assistant professor in the Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and is a board-certified pediatrician and adolescent medicine subspecialist. He is a physician researcher with clinical and research interests in the treatment and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in adolescent and young adult populations.

Laura M. Bogart a senior behavioral scientist at the RAND Corporation. A social psychologist specializing in community-based participatory research to understand and address health disparities, her primary interests are in the areas of stigma and medical mistrust and much of her research focuses on HIV prevention and treatment.

Idia B. Thurston is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Memphis. Her research interest include the biological, psychological, social, and cultural risk and protective factors related to healthy adolescent and young adult development.

Caroline H. Hu is candidate for the degree of medicine at University of Minnesota Medical School. She formerly worked as research assistant on studies focused on adolescent HIV adherence.

Margie R. Skeer is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at Tufts University. Her current research focuses on substance misuse and sexual risk prevention, both from an epidemiologic and intervention-development perspective.

Steven A. Safren is a professor of Psychology in the Department of Psychology at the University of Miami. His research program has focused on adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV treatment, primary and secondary behavioral HIV prevention interventions for in men who have sex with men (MSM), and antiretroviral therapy for HIV prevention.

Matthew J. Mimiaga is a professor of Behavioral and Social Sciences, professor of Epidemiology, professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, and director for the Center for Health Equity Research at Brown University. His research interests include behavioral medicine, infectious disease & psychiatric epidemiology, and global health. His program of research involves conducting longitudinal cohort studies, mixed methods (qualitative/quantitative) research, and developing and testing both behavioral and psychosocial treatment interventions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43:939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battles HB, Wiener LS. From adolescence through young adulthood: Psychosocial adjustment associated with long-term survival of HIV. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezabhe WM, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR, Peterson GM. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and virologic failure: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(15):e3361. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Chetty S, Giddy J, Sypek A, Sticklor L, Walensky RP, Bassett IV. Barriers to care among people living with HIV in South Africa: Contrasts between patient and healthcare provider perspectives. AIDS Care. 2012;25:843–853. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.729808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan AL, Montepiedra G, Sirois PA, Kammerer B, Garvie PA, Storm DS, Nichols SL. Barriers to medication adherence in HIV-infected children and youth based on self-and caregiver report. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1244–e1251. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. 2015;25 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/ [Google Scholar]

- Chandwani S, Koenig LJ, Sill AM, Abramowitz S, Conner LC, D’Angelo L. Predictors of anti-retroviral medication adherence among a diverse cohort of adolescents with HIV. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney M. Adherence to HAART regimens. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17:169–177. doi: 10.1089/108729103321619773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DeLaMora P, Aledort N, Stavola J. Caring for adolescents with HIV. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2006;3:74–78. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Kuhns ML, Johnson A, Holoyda JB, Garofalo R. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(2):e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Garvie PA, Lensing S, Rai SN. Efficacy of a pill-swallowing training intervention to improve antiretro-viral medication adherence in pediatric patients with HIV/AIDS. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e893–e899. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn J, Steckler A, Johnson CC, Pratt C, Grieser M, Pickrel J, Stone EJ, Conway T, Coombs D, Staten LK. Formative Research in School and Community-Based Health Programs and Studies: “State of the Art” and the Taag Approach. [In eng] Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(1):25–39. doi: 10.1177/1090198105282412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. London: Weidenfield & Nicolson; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hammell Karen Whalley. Using Qualitative Research to Inform the Client-Centred Evidence-Based Practice of Occupational Therapy. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;64(5):228–34. [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Fernandez IM, Bruce D, Hosek SG, Jacobs RJ. The role of multiple identities in adherence to medical appointments among gay/bisexual male adolescents living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0071-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JE, Jeon CY, Ivers LC, Behforouz HL, Caldas A, Drobac PC, Shin SS. Effect of directly observed therapy for highly active antiretroviral therapy on virologic, immunologic, and adherence outcomes: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;54:167–179. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d9a330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra R, Siberry GK, Mofenson LM. Growing up with HIV: Children, adolescents, and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Annual Review of Medicine. 2010;61:169–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.050108.151127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. A developmental perspective on adolescent health and illness: An introduction to the special issues. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:409–416. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek SG, Harper GW, Domanico R. Predictors of medication adherence among HIV-infected youth. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2005;10:166–179. doi: 10.1080/1354350042000326584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2014;28:1945–1956. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45:214–222. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzel C, Vandevanter N, Irvine M. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among older children and adolescents with HIV: A qualitative study of psychosocial contexts. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22:977–987. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Qualitative Research Findings as Evidence: Utility in Nursing Practice. [In eng] Clin Nurse Spec. 2010;24(4):191–3. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181e36087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Strategies for sampling. In: Morse JM, editor. Qualitative nursing research: A contemporary dialogue. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research. 2015;25:1212–1222. doi: 10.1177/1049732315588501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T, Friese S. User’s Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Sarr M, Durako SJ, Moscicki AB, Wilson CM, Muenz LR. Barriers to HAART adherence among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:249–255. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Wilson CM, Durako SJ, Muenz LR, Belzer M, The Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network Antiretroviral medication adherence among the REACH HIV-infected adolescent cohort in the USA. AIDS Care. 2001;13:27–40. doi: 10.1080/09540120020018161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Templin T, Wright K, Frey M, Parsons JT, Lam P. Psychosocial factors and medication adherence in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:44–47. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM, Perri MG. Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: An initial dismantling investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orban LA, Stein R, Koenig LJ, Conner LC, Rexhouse EL, Lewis JV, LaGrange R. Coping strategies of adolescents living with HIV: Disease-specific stressors and responses. AIDS Care. 2010;22:420–430. doi: 10.1080/09540120903193724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell RA, Single HM. Focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 1996;8(5):499–504. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power R. The Application of Qualitative Research Methods to the Study of Sexually Transmitted Infections. [In eng] Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(2):87–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.2.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2009;17:14–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, Muenz L, Ellen J. Prevalence and interactions of patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among perina-tally infected youth in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24:97–104. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1999;6:332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz KE, Lewis FME, Rimer BK, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th. 2008. pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Shuter J, Sarlo JA, Kanmaz TJ, Rode RA, Zingman BS. HIV-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy achieve high rates of virologic suppression despite adherence rates less than 95% JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;45:4–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni J, Kurth A, Pearson C, Pantalone D, Merrill J, Frick P. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel HM, Futterman DC. Adolescents and HIV: Prevention and clinical care. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2009;6:100–107. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, Montaner JS, Rizzardini G, Telenti A, Schooley RT. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston IB, Bogart LM, Wachman M, Closson EF, Skeer MR, Mimiaga MJ. Adaptation of an HIV medication adherence intervention for adolescents and young adults. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2014;21:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Palmer S, Craig JC, Strippoli GF. A Guide to Reading and Using Systematic Reviews of Qualitative Research. [In eng] Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;31(6):897–903. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener LS, Kohrt BA, Battles HB, Pao M. The HIV experience: Youth identified barriers for transitioning from pediatric to adult care. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36:141–154. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Kammerer B, Sirois PA, Malee K. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1745–e1757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I. The Person-Based Approach to Intervention Development: Application to Digital Health-Related Behavior Change Interventions. [In eng] J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: Exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2014;28:128–135. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.