Abstract

Background

Interleukin(IL)-13-producing CD8+ T cells have been implicated in the pathogenesis of type-2 driven inflammatory human conditions. We have shown that CD8+IL-13+ cells play a critical role in cutaneous fibrosis, the most characteristic feature of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma; SSc). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying IL-13 and other type-2 cytokine production by CD8+ T cells remain unclear.

Objective

Establish the molecular basis of IL-13 over-production by SSc CD8+ T cells, focusing on T-bet modulation of GATA-3 activity, which we showed to underlie IL-13 over-production in SSc CD8+IL-13+ cells.

Methods

Biochemical and biophysical methods were employed to determine expression and association of T-bet, GATA-3 and regulatory factors in CD8+ T cells isolated from the blood and lesional skin of SSc patients with severe skin thickening. ChIP analysis determined GATA-3 binding to the IL-13 promoter. ImageStream analysis and confocal microscopy visualized the subcellular localization of T-bet and GATA-3. Transcript levels were decreased by small interfering RNAs.

Results

The interaction of T-bet with the adaptor protein 14-3-3z in the cytosol of SSc CD8+ T cells reduces T-bet translocation into the nucleus and its ability to associate with GATA-3, allowing more GATA-3 to bind to the IL-13 promoter and inducing IL-13 up-regulation. Strikingly, we show that this mechanism is also found during type-2 polarization of healthy donor CD8+ T cells (Tc2).

Conclusions

We identified a novel molecular mechanism underlying type-2 cytokine production by CD8+ T cells revealing a more complete picture of the complex pathway leading to SSc disease pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis is an idiopathic disorder of connective tissue characterized by vascular damage, inflammation and tissue fibrosis (1). Cutaneous fibrosis is the most characteristic feature of SSc, resulting from excessive deposition of extracellular matrix proteins by activated dermal fibroblasts (2). This activation results from immune mediators and growth factors produced by inflammatory cells in the skin of SSc patients, ultimately leading to excessive fibrosis (3).

In previous work, we have shown that severe skin thickening in SSc is linked to IL-13 over-production by CD8+ T cells (4, 5), inducing a pro-fibrotic phenotype in normal and SSc dermal fibroblasts (5, 6). In comparison, CD4+ T cells from patients produce lower and more variable levels of IL-13 (4). Furthermore, we observed high numbers of CD8+IL-13+ cells in the fibrotic skin of SSc patients, especially in early stages of disease (5, 6). In parallel, we established that blood SSc CD8+ T cells express a high level of the transcription factor GATA-3, which correlates with the levels of IL-13 production and the extent of cutaneous fibrosis (7). Moreover, siRNA silencing of GATA-3 blocks IL-13 production in SSc CD8+ T cells (7), demonstrating a causal relationship between GATA-3 and IL-13.

GATA-3 is the master regulator of T helper (Th)2 cell differentiation and regulates expression of type-2 signature cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (8, 9). GATA-3 is also involved in the development, maintenance and effector function of other CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets, as well as in the generation of iNKT and ILC2 cells (10). Expression of GATA3 is regulated by multiple factors (8, 9), including transcription factor T-bet, a key player in the commitment of Th cells to the Th1 lineage (11). T-bet induces IFNγ transcription (11–13) and simultaneously inhibits the production of Th2 cytokines, including IL-13 (11), by antagonizing GATA-3 expression and/or function (14, 15). During Th1 differentiation, the IL-2-inducible T-cell kinase (ITK) phosphorylates T-bet at Tyr525 (16). While this modification does not affect the ability of T-bet to induce IFNγ, it facilitates the association of T-bet with GATA-3 and prevents the binding of GATA-3 to the IL-4/IL-5/IL-13 cytokine locus, resulting in suppression of type-2 cytokine production (16). We found previously that skin and blood SSc CD8+ T cells co-express high levels of IL-13 and IFNγ (4, 5), suggesting that T-bet is unable to modulate GATA-3 function (7).

The aim of this study was to determine the molecular basis underlying IL-13 up-regulation by SSc CD8+ T cells. We established that the interaction of T-bet with the adaptor protein 14-3-3z in the cytosol of SSc CD8+ T cells restricts T-bet translocation into the nucleus and its ability to associate with GATA-3. Consequently, more GATA-3 bound to the IL-13 promoter and induced IL-13 expression. Interestingly, this mechanism was not found in CD8+ T cells from healthy controls or patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but was used during type-2 priming of CD8+ T cells from healthy donors. Thus, our data identify a novel molecular mechanism underlying type-2 cytokine production by CD8+ T cells and have revealed a more complete picture of the complex pathway leading to IL-13 overexpression in SSc pathogenesis.

METHODS

Blood and skin samples

Seventy-six patients were recruited from the Scleroderma Clinic of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) who fulfilled either the classification criteria for SSc proposed by the American College of Rheumatology (17) or the diagnostic criteria of Leroy and Medsger(18). Disease subtype and internal organ involvement were assessed according to established criteria (19, 20). Based on previous studies (4, 6), we selected patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) who were in an early active disease stage (duration < 3 years) (21). These have rapidly progressive wide-spread fibrosis of the skin and early fibrosis of the lung and other internal organs (18). Patients were 29–73 years with a mean±SD of 47.5±12.7. The female-to-male ratio was 4:1. We obtained 54 blood samples and 22 full-thickness skin biopsy specimens (3mm). At the time samples were collected, patients were not treated with any immunosuppressive medications or were treated with low dose prednisone (5–10 mg/day).

Control blood (n=48) and skin samples (n=5) were obtained from age and sex-matched healthy donors with no history of any connective tissue disease, recruited at the UPMC Arthritis and Autoimmunity Center. Age range was 28–68 years and the female-to-male ratio was 3:4.

Research protocols involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh. All participants gave their written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell isolation and culture

CD8+ T cells were isolated from blood as previously reported (4). Naïve CD8+ T cells were obtained using The Naïve CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi) (7). The purity of each T-cell subpopulation was >90% as determined by flow cytometry. Cells were isolated from skin using the Whole Dissociation Skin kit (Miltenyi) (5).

When indicated, cells were activated in vitro for 5 days (Th0/Tc0) or primed under type-1 (Th1/Tc1) or type-2 (Th2/Tc2) culture conditions, as previously described (7).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qPCR)

qPCR analysis was performed as previously described (7). Human GAPDH was used as endogenous control to normalize gene expression data. All reagents and primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The SDS 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems) was used for data analysis.

Western blotting and Immunoprecipitation

Standard methods for immunoblot analysis were used(22). Additional details are reported in Supplemental Figure 2.

Flow cytometry and Amnis ImageStream

GATA-3, T-bet, and IL-13 protein expression was determined by intracellular staining as previously described (4, 7). Labeled cells were analyzed on a LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

For imaging flow cytometry, samples were acquired using the ImageStream MKII cytometer (Amnis, Merck-Millipore) and data were analyzed with the IDEAS software (Amnis).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously(6). Images were obtained with an Evos FL Auto microscope (Life Technologies). Results are expressed as a percentage of positive cells out of the entire infiltrate following quantification of 20 high-power fields (×400). The number of GATA-3+ inflammatory cells infiltrating normal and SSc skin was calculated following quantification of 20 high-power fields (HPF, ×400).

Immunofluorescence staining on frozen skin samples and blood CD8+ lymphocytes was performed as previously reported (23). Confocal images were captured on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope using an oil immersion 60× objective.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Cells were subjected to ChIP based on the ChIP-IT® High Sensitivity kit protocol (Active Motif). Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-GATA-3 mAb or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz). qPCR analysis was performed to determine the relative abundance of target DNA. DNA immunoprecipitated by GATA-3 antibody was normalized to the total DNA input.

siRNA Transfection

Freshly isolated CD8+ T cells were transfected with 4mM ITK or 14-3-3z ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA or the ON-TARGETplus Non Targeting siRNA #1 (negative control) (ThermoScientific, Dharmacon) using the Amaxa Human T Cell Nucleofector kit (Lonza), as previously described (7). ITK or 14-3-3z depletion was determined 48 hours after nucleofection by WB.

Statistical analysis

We used the unpaired Student’s t test or the one-way ANOVA followed by the post-hoc Tukey-Kramer test (InStat software, GraphPad Software). We considered p<0.05 (indicated * in figures) as significant, p<0.01 (**) as very significant, and p<0.001 (***) as highly significant.

RESULTS

CD8+ T cells from the blood and lesional skin of patients with dcSSc up-regulate GATA-3 expression and co-express high levels of T-bet

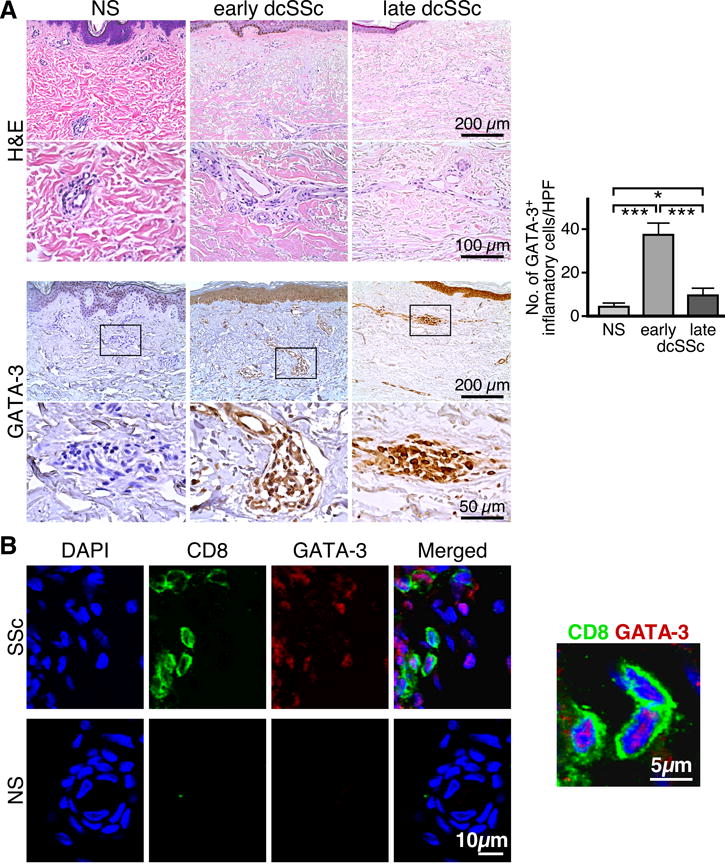

By immunohistochemical analysis, we show that high numbers of GATA-3+ cells are present in the sclerotic skin of patients (Figure 1A–B). The number of GATA-3-positive inflammatory cells is higher in the skin of patients in the early active inflammatory stage of the disease, while lower numbers are found in the skin of patients with late stage disease (Figure 1A, right panel). GATA-3-positive inflammatory infiltrates localized in the lower dermis and in the subdermal fat, while normal skin was negative for these cells. In addition to inflammatory cells, other cell types such as endothelial cells and fibroblasts express GATA-3 in SSc skin but not in normal skin (Supplemental Table I). By double-color immunofluorescence microscopy we found numerous CD8+GATA-3+ cells in the affected skin of patients with early active dcSSc (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. High numbers of CD8+GATA-3+ T cells accumulate in the sclerotic skin of patients with early dcSSc.

(A) Representative H&E stain (upper panel) and GATA-3 immunohistochemical stain (lower panel) from skin biopsies of NS (n=5), early dcSSc (n=5) or late dcSSc (n=5), each at 200× and 400×. (A, right panel). Quantification of the GATA-3-positive cellular infiltrate in tissue sections by microscopy is expressed as mean±SD of measurements from 20 HPFs. Statistics by ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test. (B) Representative examples of double color immunofluorescence staining for CD8 (surface staining) and GATA-3 (nuclear staining), 400× and 1000×. Skin samples from five early dcSSc patients were analyzed giving similar results. DAPI stains nuclei.

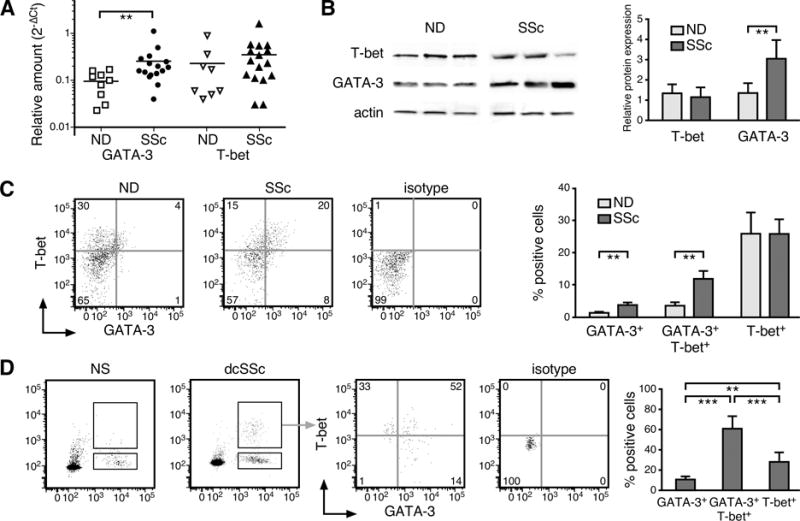

To elucidate the molecular processes associated with GATA-3 up-regulation by SSc CD8+ T cells, we analyzed T-bet modulation of GATA-3 activity. We first assessed the levels of T-bet and GATA-3 in in vitro activated naïve CD8+ T cells purified from the peripheral blood of patients with dcSSc and age-matched normal donors (NDs). The mRNA levels of T-bet and GATA-3 were determined by qPCR (Figure 2A) and the protein levels by Western blot (Figure 2B). In all experiments, we found that while the levels of GATA-3 were increased in CD8+ T cells from patients compared to controls, T-bet levels were comparable. Interestingly, by flow cytometry, we observed a statistically significant increase in the frequency of CD8+GATA-3+T-bet+ circulating lymphocytes in patient samples compared to ND CD8+ T cells (Figure 2C, P< 0.01). We next determined GATA-3 and T-bet expression by CD8+ T cells isolated from the affected skin of early dcSSc patients. Cell suspensions were prepared from 3mm skin biopsies and analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry as previously described (5). We identified CD8+ T cells from patient skin samples (Figure 2D). However, as in previous studies (5), we could not obtain sufficient CD8+ T cells from normal skin for analysis (SSc: 3.1±0.8% and ND: 0.7±0.8%). The majority of CD8+ T cells in the skin of patients co-expressed GATA-3 and T-bet, both in freshly isolated CD8+ T cells (72.3±13.8% and Figure 2D), as well as after in vitro activation (data not shown). Comparison of the frequency of CD8+T-bet+GATA-3+ T cells between blood and skin indicated that the proportion of double-positive cells was highly increased in the affected skin compared to blood (64.3±13.8% vs. 12.5±4.1%, respectively, P<0.001). Remarkably, these frequencies parallel those of CD8+IL-13+ IFNγ+ T cells found in the skin and blood of patients, respectively (5).

Figure 2. Blood and skin SSc CD8+ T cells co-express high levels of T-bet and GATA-3.

The levels of T-bet and GATA-3 were determined in naïve CD8+ T cells (CD8+CD3+CD45RA+CD27+ T cells) stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs for 5 days. (A) mRNA expression ND/SSc number (n)= 8/16 was measured by qPCR, GAPDH was used to normalize the data. Each symbol represents one patient or ND. (B) Representative Western blot for T-bet and GATA-3 protein expression (left panel) and densitometric quantification by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) (right panel, ND n=10 and SSc n=15). Actin was used as loading control. The following antibodies were used for Western blot: anti-Tbet, (Santa Cruz); anti-GATA-3, (Abcam); anti-Actin, (Sigma-Aldrich). (C–D) The percentage of T-bet+ and GATA-3+ cells measured by intracellular staining and flow cytometry in activated naïve CD8+ T cells isolated from blood (C, ND n=11, SSc n=19) or freshly isolated CD8+ T cells from skin (D, ND=5, SSc n=5) is reported. Lymphocyte population was gated according to light scatter characteristics (FSC/SSC). CD8+ T cells were identified as CD8+CD3+ cells. Representative example and quantification of frequencies of positive cells are shown. Statistics by Student’s t test in (A–C) and ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test in (D).

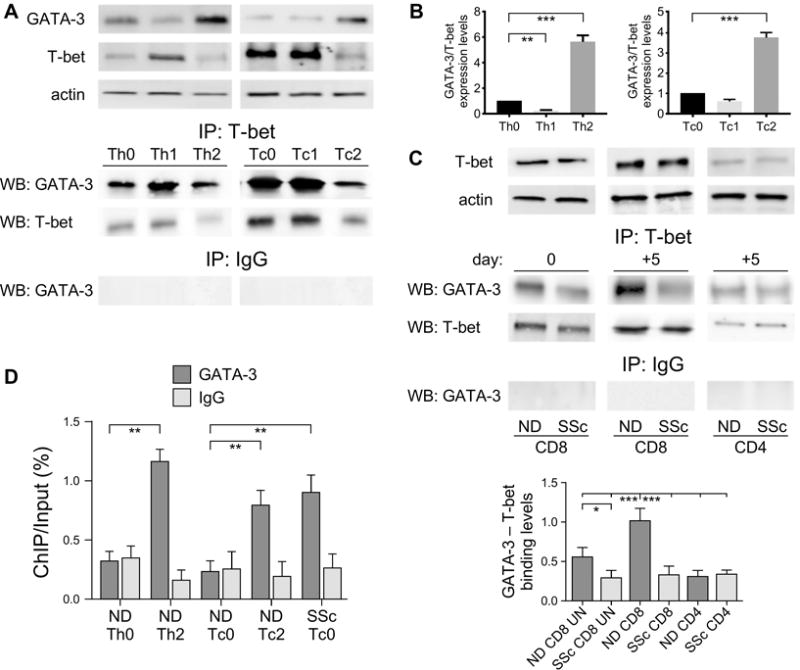

The association between T-bet and GATA-3 is reduced in SSc CD8+ lymphocytes and human Tc2 cells, allowing more GATA-3 binding to the IL-13 promoter

We purified naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from NDs and primed them in vitro in type-1 and type-2 culture conditions. After 5 days in culture, we prepared cell lysates from each cell culture to detect T-bet/GATA-3 complexes by immunoprecipitation with anti-T-bet mAb followed by immunoblotting with anti-GATA-3 mAb (Figure 3A). As observed in mouse CD4+ T cells (16), we found that the association between T-bet and GATA-3 was more pronounced in human T cells primed under type-1 culture conditions and decreased in Th2 and Tc2 cells (Figure 3A, lower panel). As expected, Th1 and Tc1 cells are characterized by low GATA-3/T-bet ratios and produced high levels of IFNγ but no IL-13, while Th2 and Tc2 cells exhibited high GATA-3/T-bet ratios and produced high levels of IL-13 and no IFNγ (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 1A–B). We next compared the interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 in CD8+ T cells isolated from a well-characterized cohort of early active dcSSc patients and age-matched NDs (Figure 3C). We found that in most of the patients analyzed the intensity of T-bet/GATA-3 association was decreased compared to NDs (Figure 3C). This was observed in freshly isolated CD8+ T cells but was more pronounced in naïve cells stimulated in vitro for 5 days (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained in activated total CD8+ T cells (data not shown). In comparison, we only detected a modest but comparable association between T-bet and GATA-3 in CD4+ T cells from SSc patients and controls, in agreement with our previous observations showing that type-2 cytokine production is more a feature of CD8 rather than CD4 T cells in SSc (4, 24) and Supplemental Figure 1C–D). Noteworthy, we observed that the interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 in CD8+ T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was similar to NDs (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3. The association between T-bet and GATA-3 is decreased in SSc CD8+ T cells compared to CD8+ T cells from healthy controls.

(A) The interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 was determined in total cell lysates prepared from ND (n=9) naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells activated in vitro (Th0, Tc0) or primed into type-1 (Th1, Tc1) or -2 (Th2, Tc2) inducing conditions. GATA-3 and T-bet expression was determined by immunoblotting (upper panel) and the ratio between GATA-3 and T-bet expression levels was assessed by densitometry (B). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-T-bet (Santa Cruz) or anti-IgG (Abcam) Abs. Immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-GATA-3 or anti-T-bet Abs. (C) Association between T-bet and GATA-3 in freshly isolated (day 0) and activated (day +5) naïve CD8+ (SSc n=25, ND n=19) and CD4+ (SSc n=8, ND n=7) T cells from dcSSc patients and age-matched NDs. Representative examples (upper panel) and densitometric quantification (lower panel) are shown. (D) ChIP analysis with anti-GATA-3 Ab (Santa Cruz) and qPCR on resulting genomic DNA were conducted on in vitro activated SSc CD8+ T cells as well as in ND Th0, Th2, Tc0, and Tc2 cells. DNA immunoprecipitated by GATA-3 Ab was normalized to the total DNA input. Negative control represents the amount of DNA immunoprecipitated by normal mouse IgG. Primers to the human IL-13 gene promoter were used for qPCR (see Methods). Error bars represent the mean±SD from 7 determinations. Statistics by ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test.

We performed ChIP analysis to determine whether the diminished interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 in SSc CD8+ T cells affected the binding of GATA-3 to the IL-13 promoter. We established that more GATA-3 bound to the IL-13 promoter of SSc CD8+ T cells compared to ND CD8+ lymphocytes but similarly to ND Tc2 and Th2 cells (Figure 3D).

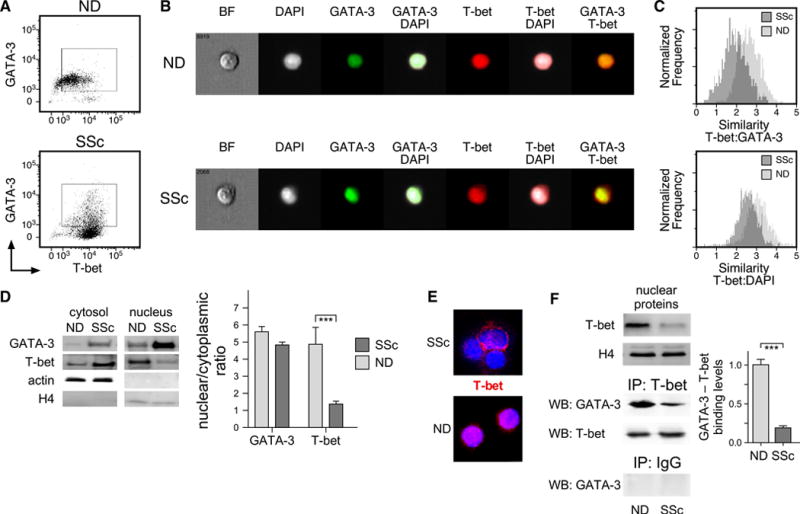

Decreased levels of nuclear T-bet correlate with a lower T-bet/GATA-3 association in dcSSc CD8+ T cells

To visualize T-bet/GATA-3 co-localization in SSc and ND CD8+ T cells on a single cell level, in vitro activated CD8+ T cells stained for T-bet and GATA-3 were analyzed with the ImageStream flow cytometer. The ImageStream technology combines flow cytometry with cell imaging to provide spatial and intensity information within individual cells (25, 26). The IDEAS software was used to calculate T-bet/GATA-3 co-localization using a Similarity Score (SS) >1, which corresponds to high correlations between T-bet and GATA-3 pixel values per cell (25, 26). Representative images of the gating strategy, histograms of Similarity Scores between a ND and an early dcSSc patient, as well as cell images from individual bins are shown in Figure 4A–C. Results highlight a diminished T-bet/GATA-3 co-localization in SSc compared to ND CD8+ T cells (ND vs. SSc T-bet+GATA-3+ SS: 2.85±0.18 vs. 2.04±0.23, respectively) and confirm the biochemical data depicted in Figure 3B. This analysis also revealed a decreased T-bet nuclear localization in SSc CD8+ T cells compared to control cells. Although T-bet exhibited a high nuclear localization in both ND and SSc CD8+ T cells, the T-bet/DAPI SS values were decreased in patient samples compared to controls (Figure 4B and 4C, lower panel; SS ND 3.18±0.17 vs. SS SSc 2.41±0.27). Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from SSc and ND CD8+ lymphocytes supported the ImageStream results (Figure 4D). The nuclear/cytoplasmic ratios of T-bet and GATA-3 levels measured in multiple samples indicated that while the GATA-3 ratios are comparable in CD8+ T cells from patients and controls, those for T-bet are greatly diminished in SSc CD8+ T cells (Figure 4D). T-bet sub-cellular localization was also evaluated by confocal microscopy. In accord with our imaging flow and cell fractionation data, we found that T-bet was almost exclusively localized in the nuclei of ND CD8+ T cells, while in SSc CD8+ T cells T-bet was detected in both nuclei and cytosol (Figure 4E). Finally, immunoprecipitation analysis of nuclear extracts from SSc and ND CD8+ cells confirmed a weaker nuclear interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 in patient CD8+ lymphocytes compared to ND cells (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Decreased levels of nuclear T-bet in SSc CD8+ T cells associated with a diminished T-bet/GATA-3 nuclear interaction.

(A–C) In vitro activated SSc (n=5) and ND (n=5) CD8+ T cells were stained for intracellular T-bet, GATA-3 and DNA (DAPI), and then analyzed by ImageStream. (A) Gating was based on single cells that were in focus and expressed T-bet and GATA-3. Representative examples are shown. (B) Brightfield (BF), T-bet (red), GATA-3 (green), DAPI (grey), and composite images for representative ND and SSc CD8+ T cells (of 6000 imaged/sample) are shown. (C) T-bet/GATA-3 co-localization (upper panel) and T-bet nuclear staining (lower panel) were analyzed in IDEAS software by comparison of T-bet staining with GATA-3 staining (upper panel) or nuclear DAPI (lower panel) in SSc and ND CD8+ T cells using the Similarity Score(25, 26). (D) T-bet and GATA-3 levels by WB in nuclear and cytosolic proteins isolated from ND (n=8) and SSc (n=11) CD8+ T cells. Actin and Histone H4 were used as loading controls. A representative example is shown (left panel). The nuclear/cytosolic ratio of all samples tested is shown (right panel). Statistics by Student’s t test. (E) Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy of CD8+ T cells fixed and stained with anti-T bet (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. (600×). (F) Nuclear proteins were isolated from CD8+ T cells of ND (n=5) and SSc (n=8) samples and immunoprecipitated with anti-T-bet or control IgG Abs. Immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-GATA-3 and anti-T-bet Abs (middle and lower panels). The expression of T-bet was evaluated by WB, H4 was used as loading control (upper panel). Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed with ImageJ (Right Panel) as described in Figure 3B.

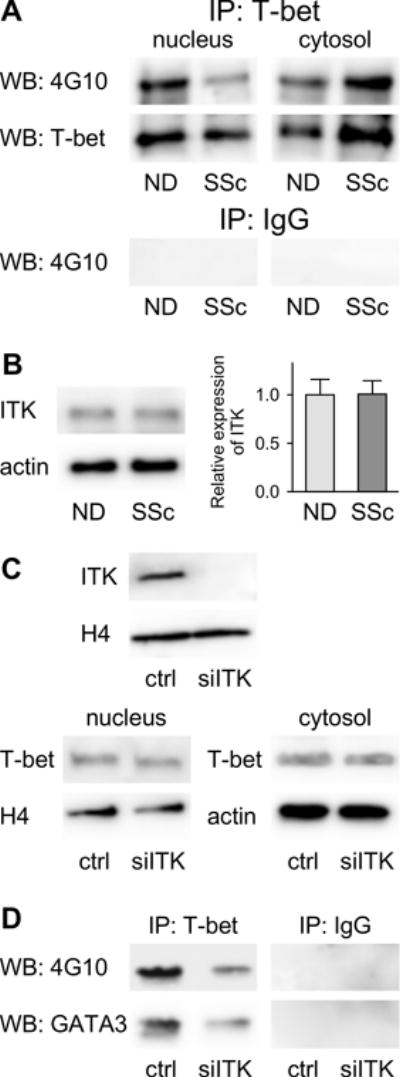

Tyrosine-phosphorylation of T-bet by ITK does not affect T-bet subcellular distribution

Tyrosine phosphorylation of T-bet protein modulates lineage commitment during T-cell differentiation (16, 27, 28). Thus, we determined the levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated T-bet in purified naïve CD8+ T cells from SSc patients and NDs after in vitro activation. Nuclear lysates obtained from cell cultures were immunoprecipitated with anti-T-bet antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-tyrosine (4G10). Levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated T-bet were found to be higher in the nucleus of ND CD8+ T cells compared to SSc samples (Figure 5A). Multiple tyrosine-phosphorylation sites have been identified on T-bet (16, 27), however T-bet phosphorylation at Tyr525 by ITK was shown to mediate the interaction between T-bet and GATA-3 (16). We established that similar levels of ITK are present in ND and SSc CD8+ T cells (Figure 5B). To determine whether ITK-dependent tyrosine-phosphorylation of T-bet affected its translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus, we determined T-bet subcellular distribution in ND CD8+ cells after ITK silencing (Figure 5C). This analysis revealed that the levels of T-bet in the nucleus and cytosol were unchanged after ITK siRNA silencing. Conversely, immunoprecipitation experiments with an anti-T-bet antibody followed by immunoblot with phospho-tyrosine or GATA-3 antibodies showed that the levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated T-bet and T-bet/GATA-3 association are both diminished after ITK siRNA (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Tyrosine-phosphorylation of T-bet by ITK regulates T-bet/GATA-3 interaction but not T-bet subcellular localization in human CD8+ T cells.

(A) Nuclear and Cytosolic proteins were extracted from CD8+ T cells (ND=5 and SSc n=8) and then immunoprecipitated with anti-T-bet or control IgG Abs. The immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with the 4G10 anti-pospho-tyrosine Ab (EMD-Millipore). (B) Representative Western blotting for ITK (anti-ITK, Abcam) protein expression in total CD8+ cell lysates. Actin was used as loading control (left panel). Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed with ImageJ (right panel, ND n= 8 and SSc n= 10). (C) ND CD8+ T cells (n=5) were transfected with siRNA for ITK or Target Control (ctrl). Expression of T-bet was analyzed by WB in nuclear and cytosolic protein extracts. Histone H4 and Actin were used as loading control. (D) Nuclear proteins isolated from ND CD8+ T cells (n=5) that were transfected with siRNA for ITK or Target Control (ctrl) were immunoprecipitated with anti-T-bet or control IgG and immunoblotted with anti-4G10 or GATA-3 antibodies (lower panel). ITK expression was analyzed by immunoblotting whereas histone H4 was used as loading control (upper panel).

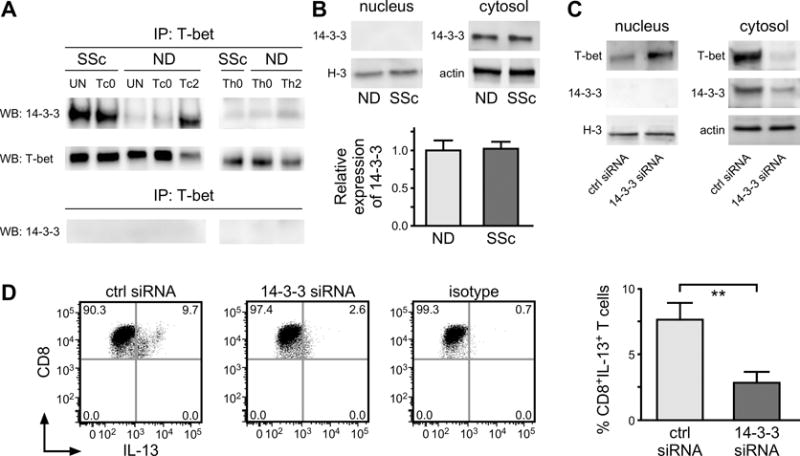

The adaptor protein 14-3-3z binds to T-bet in Tc2 and SSc CD8+ T cells and prevents its translocation to the nucleus

We performed mass spectrometry screening for T-bet immunoprecipitated proteins from patients and controls CD8+ T cells to identify potential factors that bind specifically to T-bet in SSc CD8+ lymphocytes and that might act to prevent its translocation into the nucleus. This analysis suggested that the adaptor protein 14-3-3z, which is involved in regulating subcellular localization of many transcription factors (29), interacts specifically with T-bet in CD8+ T cells from patients but not from controls (Supplemental Figure 3B).

To confirm this finding, we performed 14-3-3z immunoblot analysis of T-bet immunoprecipitated proteins from CD8+ cells from multiple patients and NDs (Figure 6A). Strikingly, we found that 14-3-3z associated with T-bet uniquely in SSc CD8+ lymphocytes but not in CD8+ cells from ND or RA patients, both in freshly isolated and in vitro activated naïve CD8+ T cells (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 2A). Importantly, we observed that 14-3-3z interacted with T-bet in ND Tc2 cells (Figure 6A). Conversely, we observed a modest and comparable interaction between 14-3-3z and T-bet in SSc and ND Th0 and Th2 cells. A preliminary test of 14-3-3z/T-bet association in CD8+ T cells compared between patients with early and late disease (defined as disease duration of less than 2 years or more than 6 years, respectively) did not reveal any significant difference (Supplemental Figure 4). 14-3-3z is only expressed in the cytosol (29, 30). By WB we demonstrated that the levels of cytosolic 14-3-3 in CD8+ T cells from patients and controls are similar (Figure 6B). To establish whether the binding of 14-3-3z to T-bet affects its sub-cellular localization, we performed 14-3-3z siRNA silencing in SSc CD8+ T cells and determined T-bet subcellular distribution by WB. After 14-3-3z down-regulation the levels of T-bet were greatly increased in the nucleus while those in the cytosol decreased (Figure 6C). Strikingly, we found that following 14-3-3z down-regulation the levels of IL-13 produced by SSc CD8+ T cells decreased as well (Figure 6D). Moreover, we observed that IL-13 production was decreased after 14-3-3 siRNA silencing in ND Tc2 cells but not in Th2 cells (Supplemental Figure 5A), which diminished their ability to induce ECM production in SSc dermal fibroblasts (Supplemental Figure 5B).

Figure 6. T-bet interaction with 14-3-3z in SSc CD8+ T cells modulates its subcellular distribution and IL-13 production.

(A) CD8+ T cell lysates prepared from SSc (n=15) and ND (n=12) patient samples were immunoprecipitated with anti-T-bet or control IgG antibodies. Immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted for anti-14-3-3 (Cell Signaling), and T-bet antibodies. (B) The expression of 14-3-3 protein was analyzed in nuclear and cytosolic lysates. Histone H3 and actin were used as loading control (left panel). Densitometric analysis of band intensity was performed with ImageJ (right panel, ND n=10, SSc n=15). (C) Nuclear and cytosolic proteins isolated from siRNA 14-3-3z or Target Control (crtl) transfected SSc CD8+ T cells were immunoblotted with anti-T bet and 14-3-3 Abs. Histone H3 and Actin were used as loading control. A representative example is shown. (D) The frequency of CD8+IL-13+ cells was determined in SSc CD8+ T cells transfected with control or 14-3-3z siRNAs. The isotype control is shown. Data from (C) and (D) are representative of seven independent experiments in 7 different individuals giving similar results. Statistics in (B) and (D) by Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

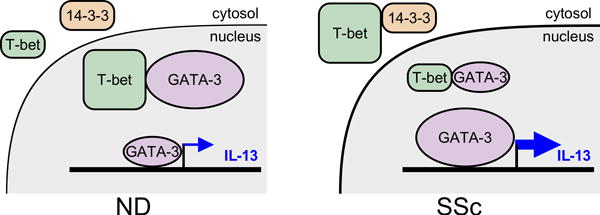

Type-2 cytokine producing CD8+ T cells (Tc2) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of several inflammatory human conditions, including asthma, COPD and atopic dermatitis (31–33). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying type-2 cytokine production by CD8+ T cells have not been elucidated. In this report, we investigated the molecular basis of IL-13 over-production by SSc CD8+ T cells, which is implicated in SSc cutaneous fibrosis. Our findings indicate that the T-bet/GATA-3 nuclear interaction is diminished in SSc CD8+ T cells compared to healthy controls, resulting in more GATA-3 becoming available to bind to the IL-13 promoter and up-regulating IL-13 expression. We show that this defect depends on the association of T-bet with the adaptor protein 14-3-3z in the cytosol of SSc CD8+ T cells, restricting T-bet translocation into the nucleus (Figure 7). Strikingly, we show that this mechanism is also found during Tc2 polarization of healthy donor CD8+ T cells, but it is not observed in CD8+ T cells from patients with RA, a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by a Th1 and Th17 phenotype (34–37). Thus, we have identified a novel molecular mechanism in the immunopathogenesis of SSc, which activates IL-13 production by CD8+ T cells. In addition, our results indicate that this mechanism likely contributes to human Tc2 cell differentiation.

Figure 7. Model for IL-13 over-production by SSc CD8+ T cells.

The schematic illustrates a mechanism through which the interaction of 14-3-3z with T-bet in the cytosol of SSc CD8+ T cells, but not of normal donors (NDs), prevents in part T-bet translocation into the nucleus and its association with GATA-3. Thus, more GATA-3 is available to bind to the IL-13 promoter and induce IL-13 expression.

SSc CD8+ T cells express higher levels of IL-13 and GATA-3 but similar levels of IFNγ and T-bet compared to NDs. Although this finding appears to contradict the traditional paradigm of Th1/Th2 cell differentiation (14, 15, 38–40), plasticity of T-cell differentiation programs has also been reported (41–47). Type I interferons induced Th2 cell reprogramming of LCMV-infected T cells (48) and enhanced IFNγ production in CD8+ lymphocytes (49). Significantly, we found an interferon signature in the affected skin (50, 51) and PBMC (52, 53) of SSc patients, which may contribute to the phenotype of SSc CD8+ lymphocytes. An additional source of IFNγ in SSc CD8+ T cells may come from the transcription factor Eomes, which has cooperative and redundant roles with T-bet in CD8 T-cell differentiation and function, including production of IFNγ (54, 55). Notably, we measured similar levels of Eomes expression by SSc and ND CD8+ T-cell subsets (data not shown), likely contributing to IFNγ expression in SSc.

An unexpected result was the finding that while the total levels of T-bet were comparable in ND and SSc CD8+ T cells, the subcellular distribution of T-bet differed. Specifically, we observed more T-bet and its active tyrosine-phosphorylated form in the nucleus of CD8+ cells from NDs compared to patients, leading to a diminished T-bet/GATA-3 interaction in the nucleus of SSc CD8+ lymphocytes. It was recently shown that subcellular distribution of T-bet and Eomes identifies functional subsets of human CD8+ T cells with increased nuclear levels in effector and effector/memory subsets and decreased levels in central memory cells (56). In our studies, we used activated total and naïve CD8+ lymphocytes as well as freshly isolated CD8+ cells, which are characterized in SSc patients by higher proportions of effector and effector/memory cells compared to controls (4, 5) and exhibit a strong cytolytic activity ex vivo (5). Yet we observed lower levels of T-bet in the nucleus of patients, suggesting that T-bet subcellular localization in SSc CD8+ T cells is likely regulated by different mechanisms.

Subcellular localization is an important mechanism controlling the effector function of many transcription factors (56–61). We analyzed whether T-bet tyrosine-phosphorylation is involved in the transport of T-bet between the cytosol and the nucleus of CD8+ T cells. In agreement with the murine model (16), we found that ITK is the kinase which is mainly responsible for tyrosine-phosphorylation of T-bet and for its interaction with GATA-3. However, our data indicate that ITK does not affect T-bet subcellular distribution. Using mass spectrometry of T-bet immunoprecipitated proteins from CD8+ T cells from dcSSc patients and controls, we showed that T-bet binds specifically to the adaptor protein 14-3-3z in the cytosol of patients but not in controls. Strikingly, we demonstrated that following silencing of 14-3-3z in SSc CD8+ T cells, more T–bet is found in the nucleus and less IL-13 is produced, demonstrating a causal relationship between 14-3-3z and IL-13 production. Remarkably, T-bet from ND Tc2 cells also appears to interact with 14-3-3z but not in CD8+ T cells purified from patients with RA. Similarly, no T-bet/14-3-3z interaction was observed in naïve and freshly isolated CD4+ T cells from SSc patients and controls as well as in ND Th2 cells, supporting our findings that this mechanism is associated with type-2 cytokine production by human Tc2 cells.

14-3-3 proteins modulate numerous cellular processes, including signal transduction, protein trafficking, cell cycle, and apoptosis, by partly affecting subcellular localization of their target proteins (29, 30, 62, 63). Here we provide the first evidence that 14-3-3z can interact with T-bet in human CD8+ T cells and this interaction restricts T-bet translocation into the nucleus and promotes type-2 cytokine production. Binding of 14-3-3 depends primarily on the phosphorylation state of its target proteins. Interestingly, multiple phosphorylation forms of T-bet have been identified, which modulate lineage commitment during T-cell differentiation (28). The predominant cytoplasmic localization of 14-3-3 proteins suggests that they might act as cytoplasmic anchors that block T-bet translocation into the nucleus. However, further studies will be necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which 14-3-3z binding to T-bet influences its subcellular localization as well as how these interactions are regulated.

In summary, we have identified a novel molecular mechanism underlying IL-13 overexpression by SSc CD8+ T cells from patients with more severe skin thickening. We also observed that CD8+ T cells from healthy controls use, at least in part, the same mechanism when primed under type-2 culture conditions, thus indicating that this mechanism is likely to be applicable to the development of Tc2 cells in other human inflammatory conditions. This more complete picture of the complex pathway leading to disease pathogenesis will aid in the development of novel markers of immune dysfunction and potential therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Lucas, BSN, MPH, for providing clinical information on the SSc patients, and Dana Ivanco, EMT-I, CCMA, CCRC, for recruiting eligible patients to this study (Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology). We also thank Mark Ross (Department of Cell Biology) for immunofluorescence confocal microscopy and Raymond K. Kong and Richard A. DeMarco (Amnis-EMD Millipore Corporation) for ImageStream analysis. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health /National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R03 AR065755, University of Pittsburgh to PF. The Scleroderma Research Fund, Taub Fund (Chicago, IL), Zale Foundation (Dallas, TX), and Shoemaker Endowment (Pittsburgh, PA) to TAM; and RiMED Foundation to SC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no competing financial interests or conflicts exist.

Author contributions

PF and SC designed experiments; TAM, RAL, and LWM provided clinical samples; PF and SC conducted experiments; PF, SC, WFH, SCW, and CM analyzed data; PF, RAL, and TAM wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(19):1989–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0806188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(3):557–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI31139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuschiotti P. Current perspectives on the immunopathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. ImmunoTargets and therapy. 2016;5:21–35. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S82037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuschiotti P, Medsger TA, Jr, Morel PA. Effector CD8+ T cells in systemic sclerosis patients produce abnormally high levels of interleukin-13 associated with increased skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(4):1119–28. doi: 10.1002/art.24432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, Larregina AT, Domsic RT, Stolz DB, Medsger TA, Jr, Lafyatis R, et al. Skin-Resident Effector Memory CD8+CD28− T Cells Exhibit a Profibrotic Phenotype in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(5):1042–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuschiotti P, Larregina AT, Ho J, Feghali-Bostwick C, Medsger TA., Jr Interleukin-13-producing CD8+ T cells mediate dermal fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):236–46. doi: 10.1002/art.37706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medsger TA, Jr, Ivanco DE, Kardava L, Morel PA, Lucas MR, Fuschiotti P. GATA-3 upregulation in CD8+ T cells is a biomarker of immune dysfunction in systemic sclerosis, resulting in excess IL-13 production. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1738–47. doi: 10.1002/art.30489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yagi R, Zhu J, Paul WE. An updated view on transcription factor GATA3-mediated regulation of Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation. Int Immunol. 2011;23(7):415–20. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tindemans I, Serafini N, Di Santo JP, Hendriks RW. GATA-3 function in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2014;41(2):191–206. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan YY. GATA3: a master of many trades in immune regulation. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(6):233–42. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100(6):655–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shnyreva M, Weaver WM, Blanchette M, Taylor SL, Tompa M, Fitzpatrick DR, et al. Evolutionarily conserved sequence elements that positively regulate IFN-gamma expression in T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(34):12622–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400849101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DU, Avni O, Chen L, Rao A. A distal enhancer in the interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) locus revealed by genome sequence comparison. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):4802–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy KM, Reiner SL. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(12):933–44. doi: 10.1038/nri954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*) Annual review of immunology. 2010;28:445–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang ES, Szabo SJ, Schwartzberg PL, Glimcher LH. T helper cell fate specified by kinase-mediated interaction of T-bet with GATA-3. Science. 2005;307(5708):430–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1103336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masi A. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(5):581–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeRoy EC, Medsger TA., Jr Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(7):1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(2):202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medsger TA, Jr, Bombardieri S, Czirjak L, Scorza R, Della Rossa A, Bencivelli W. Assessment of disease severity and prognosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(3 Suppl 29):S42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medsger TA., Jr Natural history of systemic sclerosis and the assessment of disease activity, severity, functional status, and psychologic well-being. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2003;29(2):255–73, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(03)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cascio S, Zhang L, Finn OJ. MUC1 protein expression in tumor cells regulates transcription of proinflammatory cytokines by forming a complex with nuclear factor-kappaB p65 and binding to cytokine promoters: importance of extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(49):42248–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geskin LJ, Viragova S, Stolz DB, Fuschiotti P. Interleukin-13 is overexpressed in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells and regulates their proliferation. Blood. 2015;125(18):2798–805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-590398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuschiotti P. CD8(+) T cells in systemic sclerosis. Immunol Res. 2011;50(2-3):188–94. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George TC, Fanning SL, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Medeiros RB, Highfill S, Shimizu Y, et al. Quantitative measurement of nuclear translocation events using similarity analysis of multispectral cellular images obtained in flow. J Immunol Methods. 2006;311(1-2):117–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maguire O, Collins C, O’Loughlin K, Miecznikowski J, Minderman H. Quantifying nuclear p65 as a parameter for NF-kappaB activation: Correlation between ImageStream cytometry, microscopy, and Western blot. Cytometry Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2011;79(6):461–9. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen A, Lee SM, Gao B, Shannon S, Zhu Z, Fang D. c-Abl-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of the T-bet DNA-binding domain regulates CD4+ T-cell differentiation and allergic lung inflammation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31(16):3445–56. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05383-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh S, Hwang ES. The role of protein modifications of T-bet in cytokine production and differentiation of T helper cells. Journal of immunology research. 2014;2014:589672. doi: 10.1155/2014/589672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muslin AJ, Xing H. 14-3-3 proteins: regulation of subcellular localization by molecular interference. Cellular signalling. 2000;12(11-12):703–9. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dougherty MK, Morrison DK. Unlocking the code of 14-3-3. Journal of cell science. 2004;117(Pt 10):1875–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makris D, Lazarou S, Alexandrakis M, Kourelis TV, Tzanakis N, Kyriakou D, et al. Tc2 response at the onset of COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2008;134(3):483–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betts RJ, Kemeny DM. CD8+ T cells in asthma: friend or foe? Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121(2):123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czarnowicki T, Gonzalez J, Shemer A, Malajian D, Xu H, Zheng X, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis is characterized by selective expansion of circulating TH2/TC2 and TH22/TC22, but not TH17/TC17, cells within the skin-homing T-cell population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):104–15 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nistala K, Adams S, Cambrook H, Ursu S, Olivito B, de Jager W, et al. Th17 plasticity in human autoimmune arthritis is driven by the inflammatory environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(33):14751–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003852107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada H, Nakashima Y, Okazaki K, Mawatari T, Fukushi JI, Kaibara N, et al. Th1 but not Th17 cells predominate in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(9):1299–304. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lubberts E. IL-17/Th17 targeting: on the road to prevent chronic destructive arthritis? Cytokine. 2008;41(2):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Liotta F, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Type 17 T helper cells-origins, features and possible roles in rheumatic disease. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2009;5(6):325–31. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usui T, Nishikomori R, Kitani A, Strober W. GATA-3 suppresses Th1 development by downregulation of Stat4 and not through effects on IL-12Rbeta2 chain or T-bet. Immunity. 2003;18(3):415–28. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabo SJ, Jacobson NG, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. Developmental commitment to the Th2 lineage by extinction of IL-12 signaling. Immunity. 1995;2(6):665–75. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rengarajan J, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH. Transcriptional regulation of Th1/Th2 polarization. Immunology today. 2000;21(10):479–83. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans CM, Jenner RG. Transcription factor interplay in T helper cell differentiation. Briefings in functional genomics. 2013;12(6):499–511. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinmann AS. Roles for helper T cell lineage-specifying transcription factors in cellular specialization. Advances in immunology. 2014;124:171–206. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800147-9.00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei G, Wei L, Zhu J, Zang C, Hu-Li J, Yao Z, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30(1):155–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenner RG, Townsend MJ, Jackson I, Sun K, Bouwman RD, Young RA, et al. The transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 control alternative pathways of T-cell differentiation through a shared set of target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(42):17876–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cousins DJ, Lee TH, Staynov DZ. Cytokine coexpression during human Th1/Th2 cell differentiation: direct evidence for coordinated expression of Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;169(5):2498–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Messi M, Giacchetto I, Nagata K, Lanzavecchia A, Natoli G, Sallusto F. Memory and flexibility of cytokine gene expression as separable properties of human T(H)1 and T(H)2 lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(1):78–86. doi: 10.1038/ni872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy KM, Stockinger B. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(8):674–80. doi: 10.1038/ni.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hegazy AN, Peine M, Helmstetter C, Panse I, Frohlich A, Bergthaler A, et al. Interferons direct Th2 cell reprogramming to generate a stable GATA-3(+)T-bet(+) cell subset with combined Th2 and Th1 cell functions. Immunity. 2010;32(1):116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen KB, Watford WT, Salomon R, Hofmann SR, Pien GC, Morinobu A, et al. Critical role for STAT4 activation by type 1 interferons in the interferon-gamma response to viral infection. Science. 2002;297(5589):2063–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1074900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rice LM, Stifano G, Ziemek J, Lafyatis R. Local skin gene expression reflects both local and systemic skin disease in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology. 2015 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice LM, Ziemek J, Stratton EA, McLaughlin SR, Padilla CM, Mathes AL, et al. A longitudinal biomarker for the extent of skin disease in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis & rheumatology. 2015;67(11):3004–15. doi: 10.1002/art.39287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan FK, Zhou X, Mayes MD, Gourh P, Guo X, Marcum C, et al. Signatures of differentially regulated interferon gene expression and vasculotrophism in the peripheral blood cells of systemic sclerosis patients. Rheumatology. 2006;45(6):694–702. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.York MR, Nagai T, Mangini AJ, Lemaire R, van Seventer JM, Lafyatis R. A macrophage marker, Siglec-1, is increased on circulating monocytes in patients with systemic sclerosis and induced by type I interferons and toll-like receptor agonists. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(3):1010–20. doi: 10.1002/art.22382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(12):1236–44. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearce EL, Mullen AC, Martins GA, Krawczyk CM, Hutchins AS, Zediak VP, et al. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science. 2003;302(5647):1041–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1090148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McLane LM, Banerjee PP, Cosma GL, Makedonas G, Wherry EJ, Orange JS, et al. Differential localization of T-bet and Eomes in CD8 T cell memory populations. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3207–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zabel U, Henkel T, Silva MS, Baeuerle PA. Nuclear uptake control of NF-kappa B by MAD-3, an I kappa B protein present in the nucleus. The EMBO journal. 1993;12(1):201–11. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ganchi PA, Sun SC, Greene WC, Ballard DW. I kappa B/MAD-3 masks the nuclear localization signal of NF-kappa B p65 and requires the transactivation domain to inhibit NF-kappa B p65 DNA binding. Molecular biology of the cell. 1992;3(12):1339–52. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.12.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beals CR, Clipstone NA, Ho SN, Crabtree GR. Nuclear localization of NF-ATc by a calcineurin-dependent, cyclosporin-sensitive intramolecular interaction. Genes & development. 1997;11(7):824–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu J, Shibasaki F, Price R, Guillemot JC, Yano T, Dotsch V, et al. Intramolecular masking of nuclear import signal on NF-AT4 by casein kinase I and MEKK1. Cell. 1998;93(5):851–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang JT, Ciocca ML, Kinjyo I, Palanivel VR, McClurkin CE, Dejong CS, et al. Asymmetric proteasome segregation as a mechanism for unequal partitioning of the transcription factor T-bet during T lymphocyte division. Immunity. 2011;34(4):492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chow CW, Davis RJ. Integration of calcium and cyclic AMP signaling pathways by 14-3-3. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20(2):702–12. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.702-712.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tzivion G, Shen YH, Zhu J. 14-3-3 proteins; bringing new definitions to scaffolding. Oncogene. 2001;20(44):6331–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.