Abstract

Purpose

To explore whether methods adapted from oncology pharmacological trials have utility in reporting adherence (tolerability) of exercise treatment in cancer.

Methods

Using a retrospective analysis of a randomized trial, 25 prostate cancer patients received an aerobic training regimen of 72 supervised treadmill walking sessions delivered thrice-weekly between 55% to 100% of exercise capacity for 24 consecutive weeks. Treatment adherence (tolerability) was assessed using conventional (lost to follow up (LTF) and attendance) and exploratory [e.g., permanent discontinuation, dose modification, relative dose intensity (RDI)] outcomes.

Results

The mean total cumulative “planned” and “completed” dose was 200.7 ± 47.6 MET.hrs and 153.8 ± 68.8 MET.hrs, respectively, equating to a mean RDI of 77% ± 24%. Two patients (8%) were LTF and mean attendance was 79%. A total of 6 (24%) of 25 patients permanently discontinued aerobic training prior to week 24. Aerobic training was interrupted (missing ≥3 consecutive sessions) or dose reduced in a total 11 (44%) and 24 (96%) patients, respectively; a total 185 of 1800 (10%) training sessions required dose reduction owing to both health-related (all non-serious) and non health-related adverse events (AEs). 18 (72%) patients required at least one session to be terminated early; a total of 59 (3%) sessions required early termination.

Conclusion

Novel methods for the conduct and reporting of exercise treatment adherence and tolerability may provide important information beyond conventional metrics in patients with cancer.

Keywords: Cancer, Prostate Cancer, Exercise Oncology, Safety, Tolerability, Training dose

INTRODUCTION

Structured exercise training (i.e., aerobic, resistance, or combination thereof) has gained increased attention following a cancer diagnosis to either off-set anticancer treatment-related acute and chronic toxicities (1–5) or as a potential anticancer therapy.(6–9) A field known as exercise-oncology. Parallel efforts by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and other organizations are encouraging health professionals to include exercise when designing treatment plans for patients with or at risk of chronic disease.(10) The foundation of these efforts is built on the rigor and quality of the conduct (methods) and reporting of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of exercise treatment in a given population. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines(11) and the elaboration for non-pharmacological trials(12) provide excellent frameworks for the general conduct and reporting of RCTs but do not provide standards and processes for aspects unique to exercise RCTs.

Arguably, the most important methodological consideration when designing an exercise RCT is consideration of the fundamental components of an exercise prescription (e.g., frequency, intensity, modality), and principles of training.(13) Unfortunately, description of these components in exercise-oncology trials is often missing or incomplete,(14, 15) seriously hindering study reproducibility, interpretation, and cross-study integration. This lack of information also precludes quantification of the “planned” exercise treatment dose. Several quantitative methods are available to determine exercise treatment dose in humans (e.g., average heart rate, rate of perceived exhaustion,(16) duration in heart rate zone,(17) training impulse) and although widely used in athletic populations, such metrics are rarely utilized in exercise-oncology RCTs.

Reporting of adherence (tolerability) to a “planned” prescription of exercise treatment is typically limited to rates of lost-to-follow-up (LTF) (e.g., number completing follow-up assessments) and attendance (e.g., the ratio of attended to planned treatments).(18–20) However, these variables may provide limited insight into the actual tolerability of exercise and do not permit accurate quantification of “completed” exercise dose. In oncology trials, drug dose quantification (e.g., total cumulative dose) and tolerability (e.g., rates of permanent treatment discontinuation, dose modification, dose interruption) are systematically monitored and reported according to standardized and widely accepted methods and definitions.(21–23) Whether these metrics have utility in exercise-oncology trials has not been investigated.

Against this background, we explored whether standard methods adapted from athletic performance and oncology drug trials have utility for reporting of the exercise treatment prescription and adherence (tolerability) in a previously reported RCT of aerobic training in patients with prostate cancer.(24)

METHODS

Patients and Eligibility

Full details regarding the study sample, recruitment and procedures have been reported previously.(24) Men with histologically confirmed localized prostate cancer following prostatectomy at Duke University Medical Center (DUMC) were eligible. Other major eligibility criteria were: (1) no absolute contraindications to a maximal cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), (2) willingness to travel to DUMC to attend supervised training sessions, and (3) a VO2peak below sex/age-matched sedentary values. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the DUMC institutional review board. All subjects signed a written consent prior to the initiation of any study-related procedures.

Study Design and Treatment

In this two-arm randomized controlled trial, eligible patients were randomized with an allocation ratio of 1:1 to: (1) aerobic training or (2) usual care for a total of 24 weeks. Patients were followed for 24 weeks or until disease progression or withdrawal of consent. Full details regarding the aerobic training therapy prescription have been reported previously.(24) In brief, patients received an aerobic training regimen of 72 supervised treadmill walking sessions delivered thrice-weekly for 24 consecutive weeks. The intensity of each session alternated between five different doses [i.e., 55% (zone 1), 65% (zone 2), 75% (zone 3), 85% (zone 4), 100% (zone 5)] of maximal metabolic (MET) expenditure (i.e., VO2peak). Zone 5 sessions consisted of acute bouts ranging from 30 secs to 2 mins in duration at peak workload followed by at least 1 min to 3 mins of active recovery for 4 to 20 intervals.

The actual intensity was individualized to each patient on the basis of workload (i.e., treadmill speed/grade) corresponding to a specific percent of VO2peak directly measured during the pre-randomization or midpoint (week 12) cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). The CPET was performed on a treadmill with expired gas analysis (ParvoMedics TrueOne 2400, Sandy, UT, USA).(25)Treatment dose was sequenced in such a fashion that exercise-induced physiological stress was continually altered in terms of intensity and duration in conjunction with appropriate rest and recovery sessions to optimize physiological adaptation across the entire intervention period (i.e., non-linear, periodized training).(13)

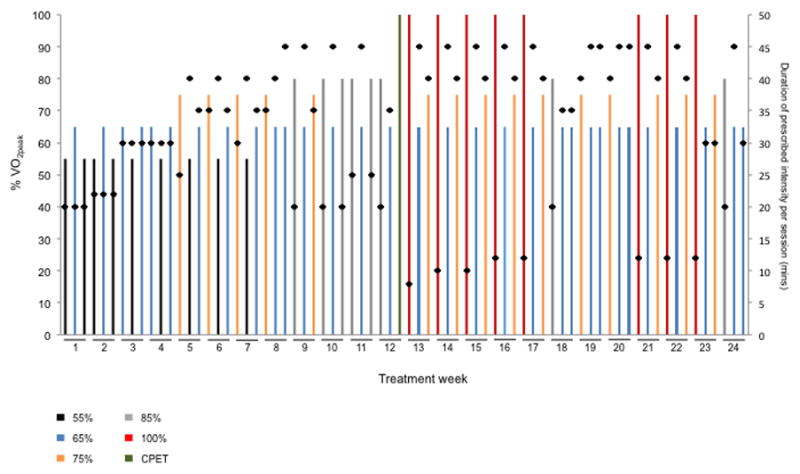

The planned intensity, duration, and sequencing of all treatment sessions are shown in Figure 1. Safety and verification of dose intensity of each session was evaluated using a combination of heart rate (continuous assessment throughout entire session), blood pressure (every 10 mins), and rate of perceived exertion (every 10 mins). Reduction in treatment dose [via intensity (treadmill speed or grade) or duration)] of any session was permitted due to health-related (e.g., elevated heart rate beyond target zone, excessive fatigue) or non health-related events (e.g., time constraints). The nature and magnitude of dose reduction was at the discretion of the exercise physiologist monitoring each session.

Fig. 1. “Planned” Aerobic Training Prescription.

Illustration of the planned, standardized aerobic training prescription template delivered to all patients allocated to the aerobic training group. The intensity and duration of each individual session (i.e., dose) as well as the sequencing of aerobic training dose across treatment weeks is presented. The intensity of each session was conducted at one of five different doses depicted by the colored bars as a percentage of VO2peak: (1) black – 55%, (2) blue – 65%, (3) orange – 75%, (4) grey – 85%, and (5) red – 100%.. Black dots depict the planned duration of each session (mins), ranging from a minimum of 20 mins/session to a maximum of 60 mins/session including warm up and cool down. At the end of Week 12, the CPET was repeated to re-prescribe exercise intensity (green bar). The prescription template depicts the planned intensity, duration, and sequencing of sessions as per protocol without any dose modification or interruption.

“Planned” dose of all sessions was quantified as METs/session. The “planned” intensity of each session was multiplied by the corresponding session target intensity duration (8–45 mins) to calculate MET/session; all sessions were summed to derive total “planned” cumulative MET-hours (MET.hrs)/patient.(26) Treatments in Weeks 1 to 12 and 13 to 24 were quantified using baseline and midpoint CPET data, respectively. Calculation of “completed” METs was quantified as the actual intensity and duration of each attended session. All sessions were summed to derive total “completed” cumulative MET-hours (MET.hrs)/patient. Relative dose intensity (RDI) was defined as the ratio of total “completed” to total “planned” cumulative dose, expressed as a percentage. A RDI of 100% indicates the aerobic training regimen was administered at the “planned” dose per protocol without any early session termination or dose modification.

Adherence (Tolerability) Outcomes

Conventional exercise trial-related tolerability variables were rates of LTF (number completing follow-up assessments), and attendance (ratio of total attended to planned treatments). Exploratory oncology drug trials-adapted adherence (tolerability) outcomes were: permanent treatment discontinuation: permanent discontinuation of aerobic training prior to week 24; treatment interruption: missing ≥3 consecutive sessions; dose modification: at least one session requiring dose reduction during training, and the total number of sessions requiring dose modification; early session termination: at least one session requiring early termination; and pre-treatment intensity modification: the intensity of at least one session required modification [e.g., planned 65% VO2peak modified to 55% VO2peak due to a pre-exercise screening indication (e.g., fatigue, time constraints)]. Rescheduling of missed sessions was permitted within the study intervention period. Safety was evaluated by the frequency of serious and non-serious events occurring during any supervised aerobic training treatment session. All events were recorded in the patients case report form by the exercise physiologist monitoring each treatment. All compliance variables are collectively counted as one entity in the same patient unless otherwise indicated.(27)

Data Analysis

Baseline medical and demographic characteristics of each group are summarized using descriptive statistics (mean/SD and frequencies). Aerobic training dose and tolerability variables are summarized by mean (SD and range, where appropriate), including all patients initially randomized to the aerobic training group (i.e., n=25). All variables are presented under the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (i.e., regardless of adherence to the aerobic training prescription).

RESULTS

Details regarding response rates, patient profile, and primary efficacy and safety data have been reported previously.(24) Characteristics of the patients assigned to aerobic training are presented in Table 1. Mean VO2peak increased +2.6 ml O2.kg−1.min−1 in the aerobic training group (p<0.001) compared to +0.4 ml O2.kg−1.min−1 in the usual care group (p=0.461).(24) For the ITT cohort, the delta percent change in VO2peak ranged from −15% to +32%. No serious (life-threatening) AEs were observed during CPET procedures or aerobic training treatment sessions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants (n=25)

| Variable | Mean/No. | SD/% |

|---|---|---|

| Age - yr | 58 | 8 |

| Weight - kg | 87.6 | 15.1 |

| Body Mass Index - kg.m−2 | 28.0 | 4.2 |

| Race – no. (%) | ||

| White | 19 | 76 |

| Black | 6 | 24 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 |

| Current smoker – no. (%) | 1 | 4 |

| Comorbid conditions – no. (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 13 | 52 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14 | 56 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 | 20 |

| CAD | 1 | 4 |

| Pulmonary disease | 9 | 36 |

| None of these comorbid conditions | 4 | 16 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||

| PSA | 5.9 | 2.6 |

| Gleason sum – no. (%) | ||

| <7 | 10 | 40 |

| ≥7 | 15 | 60 |

| Days post-surgery to randomization | 66 | 37 |

| RMR, ml O2.kg−1.min−1 | 3.9 | 0.6 |

| VO2peak, ml O2.kg−1.min−1 | 27.7 | 5.7 |

Continuous variables are reported as mean (SD) and categorical variables are reported as n (%).

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; RMR, resting metabolic rate; VO2peak, peak oxygen consumption.

Treatment Dose Quantification and Tolerability

“Planned” and “Completed” Treatment Dose

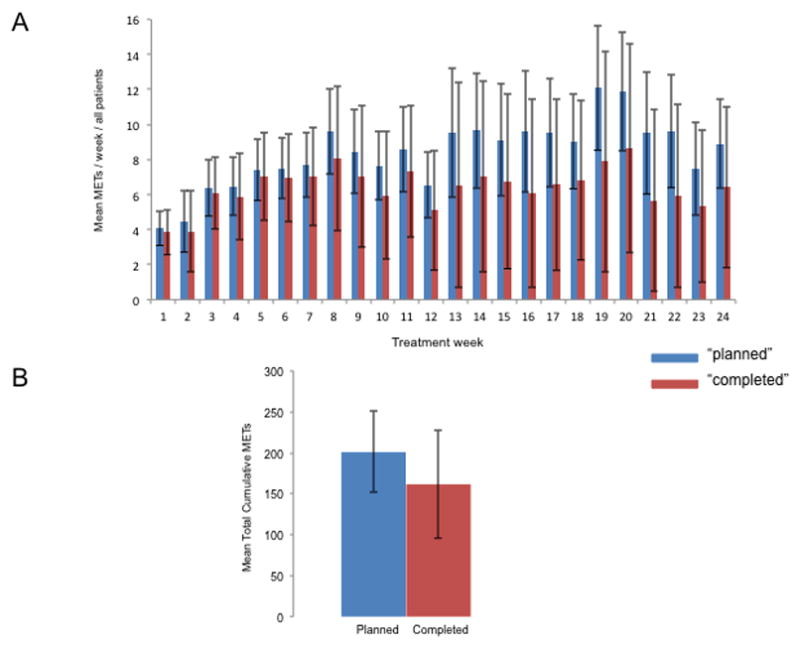

“Planned” dose of aerobic training per week was 8.4 ± 2.5 MET.hrs.wk−1 (range, 4.1 to 12.1 MET.hrs.wk−1; Fig 2A), equating to a total cumulative “planned” dose of 200.7 ± 47.6 MET.hrs (range, 123.9 to 304.6 MET.hrs; Fig. 2B). “Completed” dose per week was 6.4 ± 4.1 MET.hrs.wk−1 (range, 3.8 to 8.6 MET.hrs.wk−1; Fig 2A), equating to a total cumulative “completed” dose of 153.8 ± 68.8 MET.hrs (range, 19.7 to 291.4 MET.hrs; Fig. 2B). The mean RDI was 77% ± 25% (range, 18.4% to 100.0%; see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, Relative dose intensity calculated as total “delivered” cumulative dose divided by the total “planned” cumulative dose to derive relative dose intensity).

Fig. 2. Ratio of “planned” to “completed” aerobic training dose.

(A) Mean METs/week, and (B) total cumulative dose. Data presented for the intention to treat population including patients lost to follow up. “Planned” dose is depicted in the blue colored bars with “completed” dose depicted in the red colored bars. The average METs was assigned to sessions in which intensity was reduced (e.g., 75% reduced to 65%, imputed as 70%), whereas missed sessions were assigned zero METs.

Adherence (Tolerability)

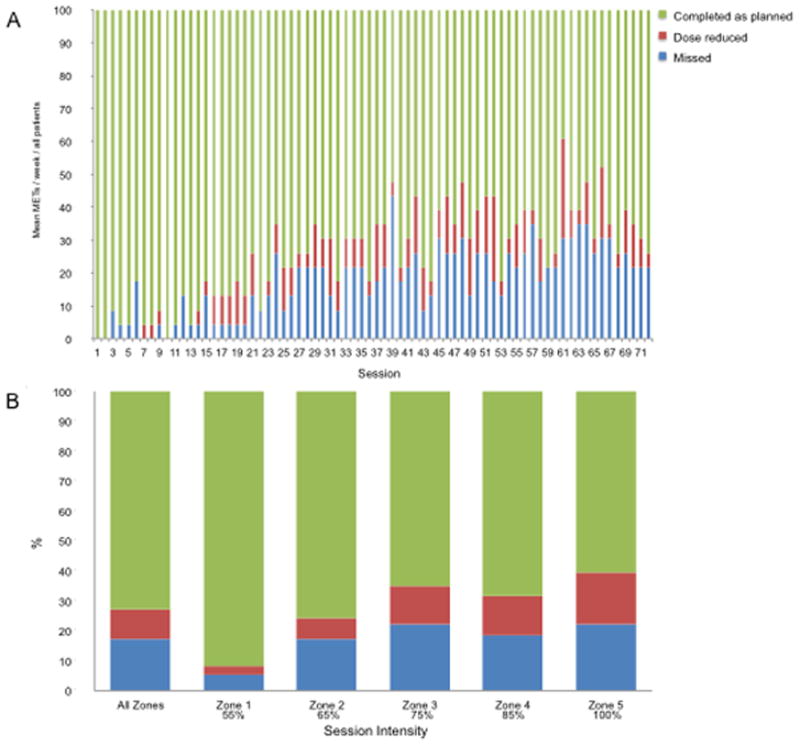

Conventional and exploratory adherence variables are summarized in Table 2. For conventional metrics, two of the 25 patients did not complete follow-up assessments at week 24, a LTF rate of 8%. The overall mean attendance was 79% ± 26% (range, 19% to 100%). For exploratory variables, a total of 6 (24%) patients permanently discontinued aerobic training prior to week 24, with treatment being discontinued in week 7, 10, 12, 14, 15 and 18 owing to health-related and non health-related reasons (Table 2). Aerobic training was interrupted in 11 (44%) of 25 patients. The main reasons for treatment interruption were non health-related reasons (e.g., vacation). A total of 24 (96%) of 25 patients required at least one treatment to be dose reduced, with a total 185 of 1800 (10%) sessions requiring dose reduction due to both health-related and non health-related reasons (Table 2; Figure 3A). On the basis of zone, the degree of dose modification was higher for zones 3, 4, and 5 training sessions (mean 14%) compared to zone 1 and 2 training sessions (mean 8%), but comparable across zones [zone 3 (13%), zone 4 (13%), and zone 5 (17%)] (Figure 3B). Over 50% of all higher-intensity training sessions that required dose modification were done so in only 6 (24%) patients. A total of 14 (56%) of 25 patients required the intensity of at least one session to be dose reduced prior to session initiation, with a total of 33 sessions (2%) required pre-session modification. A total of 18 (72%) patients required ≥1 session to be terminated early due to health-related non-serious AEs [e.g., elevated exercise heart rate (out of zone) and excessive fatigue] or non health-related reasons; a total of 59 (3%) sessions required early termination.

Table 2.

Tolerability (Adherence) to Aerobic Training

| Variable/Reasons | No. of Patients† | %* | No. of Sessions | %* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Variables | ||||

| Lost to follow upNot completing follow-up assessments | 2 | 8 | ||

| Attendance Attended/planned treatments | - | 79 | ||

| Exploratory variables | ||||

| Permanent discontinuation | 6 | 24 | 213 | 12 |

| Health-related | 3 | 12 | 124 | 7 |

| Lower extremity pain | 2 | 8 | 96 | 5 |

| Other | 1 | 4 | 28 | 2 |

| Non health-related | 3 | 12 | 89 | 5 |

| Motivational | 3 | 12 | 89 | 5 |

| Treatment interruption | 11 | 44 | 81 | 4 |

| Health-related | 2 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| Lower extremity pain | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| Dental | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Non health-related | 9 | 36 | 73 | 4 |

| Vacation | 6 | 24 | 54 | 3 |

| Not known | 3 | 12 | 19 | 1 |

| Dose modification‡ | 24 | 96 | 135 | 7 |

| Health-related | 24 | 96 | 130 | 7 |

| General exercise-related events | 16 | 66 | 58 | 3 |

| Severe fatigue | 8 | 33 | 27 | 2 |

| Lower extremity pain | 10 | 40 | 40 | 1 |

| Muscle strain | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Nausea | 1 | 4 | 2 | <1 |

| Allergic reaction | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Gastrointestinal-related | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Non health-related | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| Not known | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| Pre-treatment intensity modification | 14 | 56 | 33 | 2 |

| Not known | 14 | 56 | 33 | 2 |

| Early session termination‡ | 18 | 72 | 59 | 3 |

| Health-related | 24 | 96 | 55 | 3 |

| General exercise-related events | 15 | 62 | 42 | 2 |

| Lower extremity pain | 3 | 12 | 4 | <1 |

| Excessive fatigue | 2 | 8 | 5 | <1 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Headache | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Nausea | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Non health-related | 4 | 16 | 4 | <1 |

| Time constraints | 3 | 12 | 3 | <1 |

| Not known | 1 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

Definitions: permanent discontinuation: permanent discontinuation of treatment prior to week 24; dose interruption: missing ≥3 consecutive supervised treatments; dose modification: ≥1 treatment required dose modification, and the total number of treatments requiring a dose reduction; treatment dose intensity resequence: intensity of ≥1 treatment session required modification; and early session termination: ≥1 aerobic training sessions required early termination.

All variables are collectively counted as one entity in the same patient unless otherwise indicated.

Numbers may not add up to 100% in each section due to rounding.

Number of reasons for dose modification sums to greater than the total number of patients listed since several patients required dose modification for different reasons.

Fig. 3. (A) Aerobic training compliance per session.

Proportion of patients attending (green), requiring dose reduction (red), and missing (blue) “planned” aerobic training sessions. Data presented for the intention to treat population including patients lost to follow up. (B) Relative dose intensity across aerobic training dose intensity. Green depicts the percentage of sessions completed as planned; red depicts the percentage of sessions that required a dose reduction, while blue depicts percentage of missed sessions. Data presented for the intention to treat population including patients lost to follow up.

DISCUSSION

The CONSORT guidelines(12) and the elaboration for non-pharmacological trials(11) provide a general framework for reporting the methods of randomized trials but lack specificity. For instance, in terms of intervention methods, the non-pharmacological CONSORT standards recommend reporting: “Precise details of both the experimental and comparator. Description of the different components of the interventions” (section 4 and 4A).(12) However, such a statement is open to considerable interpretation, with “precise” description of intervention components largely at the discretion of the investigators. Arguably, a minimum requirement when reporting the methods of an exercise intervention trial is inclusion and precise description of all fundamental exercise prescription components. However, recent systematic reviews of exercise-oncology trials found that only 2 of 62 (3%) studies described all exercise prescription components and adhered to each component.(14, 15) Furthermore, when reported, description of the prescription component(s) is often vague or imprecise. For example, the reporting of the “planned” intensity of treatment sessions is often described using wide dosing ranges [e.g., 60% to 80% of maximal heart rate (HRmax)]. Although investigating prescriptions that encompass exercise training sessions between 60% to 80% of HRmax are reasonable, the optimal duration and physiological adaptations associated with sessions conducted within this broad range are distinct.(13) Unfortunately, details regarding the number of sessions conducted at a specific intensity or duration are often not reported; thus, it is not possible to discern the level of inter-patient heterogeneity in the exercise prescription dose investigated.

Another example is inadequate description of individualization of training dose intensity. The non-pharmacological CONSORT standards recommend reporting: “descriptions of the procedure for tailoring the intervention to the individual participants” (section 4A).(12) Again, the definition of “tailoring” may have several interpretations. In exercise physiology, individualization is defined as the customized application of training towards the physiological status of the patient.(13) Clearly, even within carefully selected homogenous cohorts, considerable heterogeneity likely still exists in baseline exercise capacity, exercise history, and inter-patient medical profile. Unfortunately, individualization or tailoring of exercise treatment in oncology trials is either not reported at all,(14, 15) or if reported, tailored on the basis of age-predicted HRmax. Such an approach may be limited however due to the 10 to 12–beat-per-minute variation in HRmax in normal subjects,(28, 29) with potentially even greater variation in cancer patients, given the documented impact of certain anticancer therapies on cardiac function.(30) Application of intensity dosing based on estimated HRmax could therefore result in either an under-dosing or over-dosing of exercise treatment in a given patient. Full consideration of all exercise prescription components will also permit quantification of total cumulative exercise dose. Of the many methods available(31, 32) here we quantified treatment dose using METs since it is the universally accepted metric for exercise dose quantification in epidemiological research.(33–35) The use of METs in this trial was appropriate since CPET procedures provide direct assessment (via metabolic analysis) of METs at rest and during exercise. This, in turn, permitted estimation of MET expenditure of each exercise treatment session and, therefore, the total cumulative dose of the “planned” prescription. Use of CPET procedures is considered standard practice in exercise trials among patients with chronic respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease,(36) with an increasing number of trials utilizing this tool in exercise-oncology research;(37) as such, the approach used to quantify “planned” treatment dose in the present trial is generalizable to other trials in exercise-oncology research.

Full reporting of exercise prescription methods is arguably futile without parallel precise reporting of exercise treatment adherence (tolerability). The CONSORT standards for non-pharmacological trials,(12) as well as the recent Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT),(20) provide limited guidance. The widely reported metrics exercise trials are the rates of LTF and attendance. In the present trial, rates of LTF and attendance were 8% and 79%, respectively, consistent with that reported in prior trials. (19). Novel methods explored here however indicate that LTF and attendance may provide limited insight into the true tolerability of exercise treatment. For instance, while two patients were LTF, six (24%) permanently discontinued exercise treatment prior to week 24. Furthermore, attendance simply provides data on the number of “planned” treatment sessions missed but no information on the timing of missed sessions or adherence to prescribed dose. The dose interruption rate (missing ≥3 consecutive treatments) in the present trial was 44%. Presentation of such data not only provides important data regarding the tolerability of treatment but also may reveal patterns when patients are more likely to miss consecutive treatments or explain null findings. It is noteworthy that virtually all patients required the dose of at least one session to be reduced, with almost 10% of all “planned” treatment requiring a dose reduction. The attendance rate for these sessions, however, would be reported as 100%, indicating the limited insight provided by this metric. The present findings also indicate that the extent of dose modification was higher for higher intensity exercise sessions (i.e., zones 3, 4, and 5) compared to lower intensity sessions (i.e., zone 1 and 2) potentially leading to the conclusion that higher-intensity exercise training may have limited feasibility or tolerability in men with localized prostate cancer. However, the overall dose modification rate for these sessions was low overall (14%) and comparable across zones (range: 13% to 17%); furthermore, >50% of these sessions were modified in only 6 patients. On the basis of this data, we contend that higher-intensity training is feasible/tolerable (and safe) for the majority of patients in this setting, but not all patients – there is variability in exercise feasibility/tolerability. An important objective for future work is the conduct of phase 1/2-esque studies specifically designed to evaluate the safety and tolerability of exercise training in specific settings and identify the characteristics of patients for which exercise is feasible/tolerable as well as those for which exercise is not.(38) These critical vanguard studies will not only evaluate the true tolerability of exercise in cancer populations but also inform the eligibility criteria for future definitive trials testing the efficacy of exercise in a particular clinical setting.

An added advantage of quantification of total “planned” dose together with use of novel treatment adherence metrics is that it permits accurate quantification of the “completed” treatment dose. Several trials have reported duration in target heart rate zone as a measure of “completed” dose but while this metric provides superior information than attendance, reliance on heart rate is limited in certain clinical populations since heart rate response to exercise is often abnormal due to concomitant medications (e.g., beta-blockers, polychemotherapy). As a potential complementary approach, we calculated the ratio of “completed” to “planned” total cumulative dose to calculate RDI – a widely used metric in oncology drug trials. Although cross-trials comparisons are not yet possible, the mean RDI of 77% demonstrates that the planned exercise dose was, for the most part, adequately completed, and therefore tested, in the present trial.

This study has several important limitations. First, the generalizability of these exploratory retrospective findings are limited to a small cohort of relatively healthy men with localized disease not receiving any form of anticancer therapy. Larger, prospective studies across diverse oncology scenarios are required. Second, we only evaluated the utility of the selected adherence (tolerability) metrics to a supervised RCT of aerobic training; the applicability to non-supervised or resistance training requires investigation, as does accurate monitoring of non-protocol exercise and general physical activity.(39) Third, we did not directly assess MET expenditure during aerobic training sessions but rather estimated METs expenditure on the basis of CPET data (at baseline or midpoint), potentially leading to miscalculation of the “completed” dose. Finally, in this report we focused attention on the aerobic training (intervention) group but equally important is monitoring of patients allocated to comparator groups, especially the degree of physical activity/exercise performed by patients assigned to non-exercise control groups (i.e., contamination).(39)

In summary, conduct and reporting methods adapted from athletic performance and oncology pharmacological trials may provide a novel and important approach for the conduction and reporting of exercise treatment trials in cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from the National Cancer Institute (R21-CA133895) awarded to LWJ. TSN, LWJ, JS, CC, and MM are supported by the Kalvi Trust, AKTIV Against Cancer and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748). The authors would like to thank Whitney Underwood for administrative support. Authors declare no conflict of interests. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

Footnotes

Nilsen et al. Supplementary Fig. 1.docx—Relative dose intensity calculated as total “delivered” cumulative dose divided by the total “planned” cumulative dose to derive relative dose intensity (RDI).

References

- 1.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(7):664–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4605–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segal RJ, Reid RD, Courneya KS, et al. Randomized controlled trial of resistance or aerobic exercise in men receiving radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):344–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvao DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Joseph D, Newton RU. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):340–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Field CJ, Fairey AS. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(9):1660–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2479–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones LW, Kwan ML, Weltzien E, et al. Exercise and Prognosis on the Basis of Clinicopathologic and Molecular Features in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: The LACE and Pathways Studies. Cancer Res. 2016;76(18):5415–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(22):3535–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones LW. Precision Oncology Framework for Investigation of Exercise as Treatment for Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(35):4134–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.7687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Sports M [Internet] Available from: http://www.exerciseismedicine.org/

- 11.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, Group C. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, Group CN. CONSORT Statement for Randomized Trials of Nonpharmacologic Treatments: A 2017 Update and a CONSORT Extension for Nonpharmacologic Trial Abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):40–7. doi: 10.7326/M17-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasso JP, Eves ND, Christensen JF, Koelwyn GJ, Scott J, Jones LW. A framework for prescription in exercise-oncology research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6(2):115–24. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winters-Stone KM, Neil SE, Campbell KL. Attention to principles of exercise training: a review of exercise studies for survivors of cancers other than breast. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(12):987–95. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell KL, Neil SE, Winters-Stone KM. Review of exercise studies in breast cancer survivors: attention to principles of exercise training. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(13):909–16. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2010-082719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sylta O, Tonnessen E, Seiler S. From heart-rate data to training quantification: a comparison of 3 methods of training-intensity analysis. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9(1):100–7. doi: 10.1123/IJSPP.2013-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Marroyo JA, Villa G, Garcia-Lopez J, Foster C. Comparison of heart rate and session rating of perceived exertion methods of defining exercise load in cyclists. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(8):2249–57. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(2):87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones LW. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: cancer. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(Suppl 1):S101–12. doi: 10.1139/h11-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and Elaboration Statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1428–37. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyman GH. Impact of chemotherapy dose intensity on cancer patient outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(1):99–108. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenhart C. Relative dose intensity: improving cancer treatment and outcomes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(4):757–64. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.757-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vavra KL, Saadeh CE, Rosen AL, Uptigrove CE, Srkalovic G. Improving the relative dose intensity of systemic chemotherapy in a community-based outpatient cancer center. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(5):e203–11. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones LW, Hornsby WE, Freedland SJ, et al. Effects of nonlinear aerobic training on erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular function following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(5):852–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Thoracic S, American College of Chest P. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):211–77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones LW, Peddle CJ, Eves ND, et al. Effects of presurgical exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness among patients undergoing thoracic surgery for malignant lung lesions. Cancer. 2007;110(3):590–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dang C, Fornier M, Sugarman S, et al. The safety of dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with trastuzumab in HER-2/neu overexpressed/amplified breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(8):1216–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairbarn MS, Blackie SP, McElvaney NG, Wiggs BR, Pare PD, Pardy RL. Prediction of heart rate and oxygen uptake during incremental and maximal exercise in healthy adults. Chest. 1994;105(5):1365–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.5.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panton LB, Graves JE, Pollock ML, et al. Relative heart rate, heart rate reserve, and VO2 during submaximal exercise in the elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(4):M165–71. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.4.m165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moslehi JJ. Cardiovascular Toxic Effects of Targeted Cancer Therapies. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375(15):1457–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1100265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster C, Daines E, Hector L, Snyder AC, Welsh R. Athletic performance in relation to training load. Wis Med J. 1996;95(6):370–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mujika I. Quantification of Training and Competition Loads in Endurance Sports: Methods and Applications. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12(Suppl 2):S29–S217. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1993;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manson JE, Greenland P, LaCroix AZ, et al. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(10):716–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Cohort Study. JAMA. 2003;290(10):1331–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman DE, Arena R, Boxer R, et al. Prioritizing Functional Capacity as a Principal End Point for Therapies Oriented to Older Adults With Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(16):e894–e918. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haykowsky MJ, Scott JM, Hudson K, Denduluri N. Lifestyle Interventions to Improve Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Reduce Breast Cancer Recurrence. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Meeting. 2017;37:57–64. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_175349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones LW. Precision Oncology Framework for Investigation of Exercise As Treatment for Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(35):4134–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.7687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steins Bisschop CN, Courneya KS, Velthuis MJ, et al. Control group design, contamination and drop-out in exercise oncology trials: a systematic review. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0120996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.