Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the experience of financial stress for patients who survive critical illness or their families. Our objective was to describe the prevalence of financial stress among critically ill patients and their families, identify clinical and demographic characteristics associated with this stress, and explore associations between financial stress and psychological distress.

Design

Secondary analysis of a randomized trial comparing a coping skills training program and an education program for patients surviving acute respiratory failure and their families.

Setting

Five geographically diverse hospitals.

Participants

Patients (n=175) and their family members (n=85) completed surveys within 2 weeks of arrival home and 3 and 6 months after randomization.

Measurements and Main Results

We used regression analyses to assess associations between patient and family characteristics at baseline and financial stress at 3 and 6 months. We used path models and mediation analyses to explore relationships between financial stress, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and global mental health. Serious financial stress was high at both time points, and was highest at 6 months (42.5%) among patients and at 3 months (48.5%) among family members. Factors associated with financial stress included female sex, young children at home, and baseline financial discomfort. Experiencing financial stress had direct effects on symptoms of anxiety (β=0.260, p<0.001) and depression (β=0.048, p=0.048).

Conclusions

Financial stress after critical illness is common and associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. Our findings provide direction for potential interventions to reduce this stress and improve psychological outcomes for patients and their families.

Keywords: financial stress, financial burden, stress, psychological/economic, critical illness, psychological distress

Introduction

As more patients survive critical illness, the long-term consequences on their quality of life are evident in impairments in physical, cognitive, and psychological function (1–4). In particular, psychological distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety, is reported by up to 60% of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors and 70% of patients’ family members at one year after ICU discharge (5–12). Therefore, identifying and addressing specific stressors that contribute to this distress could help to improve quality of life within this population.

Financial stress has been reported by critically ill patients and their family members, although little is known about its prevalence, duration, or impact on the experience of ICU survivorship (13, 14). Among patients with cancer, financial distress is associated with worse clinical outcomes and decreased quality of life (15). In one study, patients with advanced cancer reported financial stress to be more severe than physical, family, or emotional distress (16). The objectives of our study were to investigate the extent to which surviving ICU patients and their family members reported financial stress and to identify patient and family characteristics associated with reporting this stressor. Last, we sought to explore the relationships among financial stress and anxiety, depression, and global mental health.

Methods

Design Overview

Data were collected as part of a randomized trial comparing a post-ICU discharge coping skills training program to a critical illness education program among patients and their family members (17). The study was conducted at five academic and community hospitals in the United States (Duke Medical Center, Duke Regional Hospital, University of Washington, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, UPMC Presbyterian Hospital); patients were enrolled between December 2013 and April 2015. Eligible patients were age ≥18 years with receipt of mechanical ventilation for >48 consecutive hours and successful extubation before ICU discharge. Eligible family members were aged ≥18 years and expected to provide significant post-discharge assistance. If available, one family member for each patient was allowed to participate. Patients without an available family member were also eligible. Patient exclusions included pre-existing or current cognitive impairment at time of hospital discharge, treatment for severe mental illness during the 6 months preceding admission, residence at a location other than home immediately before admission, poor English fluency, ICU attending’s expectation of survival less than 3 months, inability to complete study procedures as determined by study staff, or failure to return home within 3 months after discharge. Exclusions for family members included history of cognitive impairment or poor English fluency.

Trained research coordinators collected clinical data from patients’ electronic health records. Participants completed study surveys by telephone with a research coordinator or by a password-protected electronic patient-reported outcomes system at three time periods: within 2 weeks after arrival home (interview #1, time of randomization), 3 months (interview #2), and 6 months (interview #3) post-randomization. Institutional review boards of the participating sites approved the study protocol.

Measures

Outcomes

The primary patient outcome for our analyses was financial stress, a variable constructed from patients’ free-text response to the question “What are the most stressful things [up to three] in your life right now?” This variable was coded by reviewers with expertise in qualitative methods, using content analysis (18). We defined financial stress as a binary outcome (1 = financial stress was mentioned as one of these stressors, 0 = no mention of financial stress as one of the top three stressors). Secondary patient outcomes were patients’ anxiety and depression symptoms, modeled as continuous latent variables that fit the observed data, and based on responses to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (19). Global mental health was measured using a single-item five-point rating of mental health (20). Financial stress was the sole outcome of interest for family members given the small family sample size (n=85). Additional details on study measures can be found in eSupplement, eMethods 1.

Risk factors

Our analyses were guided by prior studies examining the influence of acute health events on financial stress (21–24). Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we began the process of identifying potential patient risk factors for the financial stress outcome by selecting all 27 available patient measures that suggested a potential conceptual link to financial stress (see eSupplement, eMethods 2). We used the same strategy to develop a set of potential family member risk factors for the financial stress outcome and began with 31 variables that had conceptual links to financial stress (see eSupplement, eMethods 3).

Statistical Analysis

After performing descriptive analyses of the characteristics of patients and family members as well as the prevalence of financial stress, we examined trends in financial stress for these two groups over time. The first analyses included only respondents who completed all three surveys (eTable 1a) and were based on probit regression models estimated with weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment (WLSMV), with the three post-discharge assessments clustered under respondent. The binary financial stress variable was regressed on assessment point (coded as 1, 2, 3). We also tested assessment point as an additional quadratic term and retained that variable in the final model if it was statistically significant.

Second, we identified patient and family characteristics associated with financial stress using clustered probit regression models, but including all participants who responded to one or more surveys. For the patient sample we first regressed financial stress on each individual variable in the set of potential predictors (including site as a covariate if its addition to the bivariate model changed the p-value for the predictor by 10% or more) and eliminated from further consideration all variables with p-values >0.20. We then ran a multi-predictor model with the retained variables, identifying as significant independent contributors to financial stress all predictors with p<0.05; the multi-predictor model included confounder adjustment for site. Because of the small size of the family member sample, we ran only the unadjusted model for each potential predictor and report the results for all predictors with bivariate p<0.20.

Last, we developed and tested causal hypotheses relating patients’ self-ratings of their global mental health, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression, with their reports of financial stress and its predictors. Preliminary to development of these models, we used exploratory factor analysis in a confirmatory factor analysis framework to identify a simplified two-factor structure that would conceptually reflect anxiety and depression and that had adequate fit to the patient sample (25). Using the quality-of-life rating and the latent anxiety and depression constructs as mediators between financial stress and patients’ ratings of their mental health, we tested three potential effects of each predictor on each outcome: the direct effect (i.e., the part of the effect that was not mediated by another measured variable), the indirect effect through a mediator (i.e., the product of the direct effect of the predictor on a mediator and the mediator’s direct effect on the outcome), and the total effect (the sum of the direct and indirect effects). More detail on the statistical approach is found in the eSupplement, eMethods 4.

We used SPSS 19 (http://www.ibm.com/analytics/us/en/technology/spss/) for descriptive statistics and Mplus 7.4 (http://www.statmodel.com/) for regression modeling.

Results

Sample characteristics

Patients

One hundred and seventy-five patients were randomized (86 to coping skills training, 89 to education). The mean age was 51.7 (SD: 13.8). A total of 43% were female and 30% were racial/ethnic minorities. Patients who were commercially insured represented 44% of the sample; 33.7% were insured by Medicare, 16% by Medicaid, and 6% had no health insurance. The majority of patients were treated in a medical ICU (48%); median length of stay was 8 days (IQR: 8.0). Mean Apache II score was 25.8 (SD 8.2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patient and Family Samples at Baseline Assessment

| Characteristic | Patients | Family | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid n | Statistica | Valid n | Statistica | |

| Female | 175 | 75 (42.9) | 85 | 68 (80.0) |

| Racial/ethnic minority | 173 | 51 (29.5) | 84 | 14 (16.7) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 175 | 51.7 (13.8) | 85 | 51.4 (15.0) |

| Highest level of education completed | 175 | 83 | ||

| High school or less | 73 (41.7) | 34 (40.9) | ||

| Trade, vocational, or technical school | 10 (5.7) | 4 (4.8) | ||

| Associate’s degree or some college, but without a degree | 57 (32.6) | 24 (28.9) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or graduate work | 35 (20) | 21 (25.3) | ||

| Marital status | 175 | 84 | ||

| Currently married | 89 (50.9) | 60 (71.4) | ||

| Insurance | 175 | |||

| Medicare | 59 (33.7) | |||

| Medicaid | 28 (16.0) | |||

| Commercial | 77 (44.0) | |||

| None | 11 (6.3) | |||

| ICU type | 175 | |||

| Medicine | 83 (48.0) | |||

| Trauma | 25 (14.3) | |||

| General surgery | 34 (19.4) | |||

| Neurology/neurosurgery | 11 (6.3) | |||

| Cardiology | 21 (12.0) | |||

| APACHE II Score, mean (SD) | 175 | 25.83 (8.22) | ||

| Number of days in ICU, median (IQR) | 175 | 8.0 (8.0) | ||

| Lived with patient | 83 | 66 (79.5) | ||

| Relationship to patient | 85 | |||

| Spouse / partner | 47 (55.3) | |||

| Child | 10 (11.8) | |||

| Parent | 11 (12.9) | |||

| Other | 17 (20.0) | |||

| Paid employment status | 164 | 69 | ||

| Employed part or full time | 68 (41.5) | 31 (44.9) | ||

| Extent felt financially comfortable | 174 | 83 | ||

| Barely enough or needed more money for bills and basic needs | 63 (36.2) | 32 (38.6) | ||

| Enough money for a few extra things | 68 (39.1) | 27 (32.5) | ||

| Financially comfortable | 43 (24.7) | 24 (28.9) | ||

| Any children under age 10 living at home | 175 | 20 (11.4) | 85 | 6 (7.1) |

Unless otherwise noted, the statistic provided is the n (%) having the characteristic.

Family members

Eighty-five family members were included in the study (39 coping skills training, 47 education) with a mean age of 51 years old (SD 15); roughly 80% of them were female. Nearly 80% lived with the patient, 55.3% were the spouse or partner, and most (55.1%) were not employed (Table 1).

Prevalence of financial stress

At interview #1, 28.6% of patients reported financial stress as one of the top 3 stressors, 36.8% at interview #2 and 42% at interview #3 (eTable 1, eFigure 1). For family members, 32.1% reported financial stress as a top stressor at interview #1; 48.5% at interview #2 and 38.5% at interview #3. The proportion of patients reporting financial stress had a significant linear trend (β = 0.183; p = 0.002). For family members, the effect of time was curvilinear, rising at 3 months and then falling at 6 months (β for linear time = 1.448, p = 0.013; β for quadratic term = −0.342, p = 0.017; Wald test for the combined linear and quadratic effects of time, p = 0.040) (eFigure 1a).

Factors associated with financial stress over time

Bivariate models of each potential patient predictor resulted in elimination of 15 variables because of p-values >0.20 (see eSupplement, eMethods 2, for list of eliminated predictors). Among the 12 variables that remained, factors independently associated with patient financial stress in multi-predictor models were female gender, financial comfort at baseline, and children < 10 years old at home (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of Predictors with Patients’ Experience of Financial Stressa

| Predictor | Valid nd | Single-Predictor Modelsb | pe | Valid nd | Multi-Predictor Modelc | pe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |||||

| Female | 442/175 | 0.519 | 0.191, 0.848 | 0.002 | 405/161 | 0.478 | 0.110, 0.846 | 0.011 |

| Racial/ethnic minority | 436/173 | 0.306 | −0.044, 0.656 | 0.086 | 0.168 | −0.233, 0.568 | 0.412 | |

| Age in years, baseline | 442/175 | −0.015 | −0.028, −0.001 | 0.029 | 0.006 | −0.014, 0.026 | 0.546 | |

| Marital status, baseline | 442/175 | 0.059 | 0.459 | |||||

| Currently married | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Previously married | 0.260 | −0.122, 0.641 | 0.269 | −0.154, 0.693 | ||||

| Never Married | 0.488 | 0.079, 0.897 | 0.118 | −0.350, 0.586 | ||||

| Insurance, baselinef | 442/175 | 0.091 | 0.065 | |||||

| Medicare | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Medicaid | 0.480 | −0.031, 0.991 | 0.404 | −0.192, 0.999 | ||||

| Commercial | 0.179 | −0.207, 0.565 | 0.443 | −0.057, 0.943 | ||||

| None | 0.664 | 0.041, 1.288 | 0.848 | 0.182, 1.515 | ||||

| Cancer as chronic comorbidity | 442/175 | −0.563 | −1.027, −0.098 | 0.018 | −0.478 | −1.122, 0.165 | 0.145 | |

| Financially comfortable, baselineg | 441/174 | −0.309 | −0.458, −0.161 | <0.001 | −0.235 | −0.408, −0.061 | 0.008 | |

| Any children under age 10 living at home, baseline | 442/175 | 0.606 | 0.100, 1.113 | 0.019 | 0.707 | 0.106, 1.309 | 0.021 | |

| Decreased employment from baseline to follow-uph | 414/164 | 0.285 | −0.008, 0.577 | 0.056 | 0.227 | −0.121, 0.575 | 0.200 | |

| Social support, follow-upi | 440/175 | −0.204 | −0.337, −0.071 | 0.003 | −0.130 | −0.296, 0.035 | 0.123 | |

| Emotional health, follow-upj | 441/175 | −0.175 | −0.297, −0.053 | 0.005 | −0.021 | −0.172, 0.130 | 0.785 | |

| Quality of life, follow-upk | 441/175 | −0.183 | −0.331, −0.034 | 0.016 | −0.092 | −0.270, 0.086 | 0.309 | |

Associations are based on clustered probit regression models (three post-discharge assessment points clustered under patient), estimated with weighted mean- and variance adjusted least squares (WLSMV). The outcome was coded 1 if the patient reported financial stress as one of the top three stressors at the point of the assessment; and 0 if financial stress was not one of the three top stressors or if the patient reported experiencing no stress of any kind.

Except where noted, financial stress was regressed only on the variable (or set of dummy indicators) indicated in the row heading.

Financial stress was regressed simultaneously on all predictors, with adjustment for site.

The valid n is expressed as the number of assessments with valid responses / number of patients providing some valid data at one or more assessment points.

P-values for unordered categorical predictors were based on Wald’s test of parameter constraints.

The “single-predictor” model was adjusted for site.

How the patient felt at the end of an average month, when paying bills: 1=short on money and needed more for bills and basic needs, 2=barely enough for bills and basic needs, 3=enough for just a few extra things, 4=completely comfortable.

Decreased employment: 0=change to employment expected to provide higher pay (e.g. from part-time at baseline to full-time at follow-up, or from not employed for pay at baseline to employed for pay at follow-up); 1=no change (in the same category – FT/PT/no pay – at both time points); 2=change to employment expected to provide lower pay.

Frequency of having someone to confide in or talk to about problems: 1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=usually, 5=always

Frequency in past 7 days of being bothered by emotional problems such as feeling anxious, depressed, or irritable: 1=always … 3 = sometimes … 5=never

Self-assessed quality-of-life rating: 1=poor, 3=good, 5=excellent

For family members, unadjusted models of reported financial stress with individual predictors showed significant associations (p<0.05) with lower level of education, marital status, baseline financial discomfort, emotional health, and quality of life (eTable 2).

Association of financial stress with anxiety, depression, and global mental health

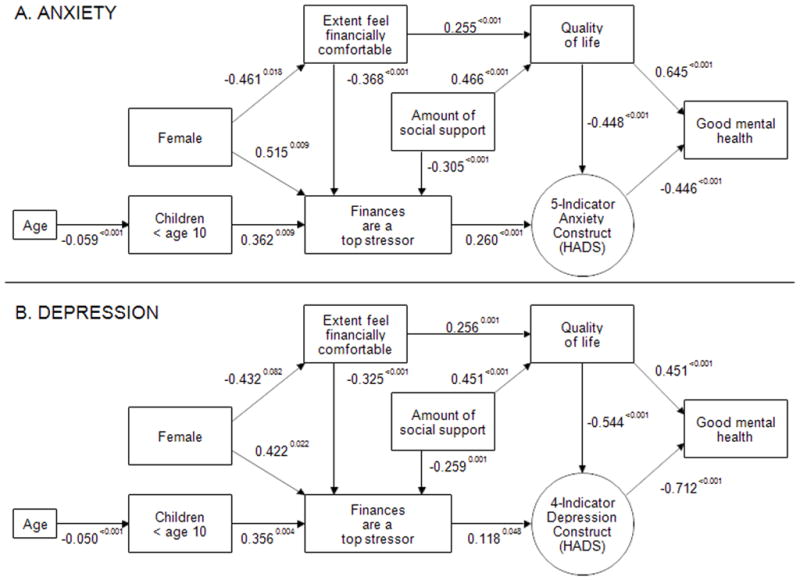

Financial stress had a direct effect on symptoms of anxiety (β = 0.260, p<0.001). Using patients’ symptoms of anxiety as a mediator, the path model displayed in Figure 1A supports several causal hypotheses, including the following: 1) younger patients are significantly more likely to have children under age 10 living with them, and because of this, are significantly more likely to experience financial stress, increased anxiety, and reduced global mental health; 2) the presence of social support significantly improves quality of life and decreases the extent to which financial concerns are important stressors for patients, and through these variables, reduces anxiety and improves global mental health; and 3) financial stress has a direct impact on increased anxiety and makes an indirect contribution through anxiety to reduced mental health.

Figure 1. Path Models of Hypothesized Effects of Patients’ Financial Stress and Its Precursors on Quality of Life, Anxiety and Depression Symptoms, and Global Mental Health.

(A) Based on R2 estimates, the model accounts for 22.1% of the variance in patients’ perceptions of their quality of life, 37.0% of the variance in the existence of financial stress as one of the top three stressors, 30.7% of the variance in the latent anxiety construct, and 54.1% of the variance in patients’ self-assessed mental health status. All of these values have associated p <0.001. The p-value for the χ2 test of fit of this model to the observed data = 0.0854.

(B) Based on R2 estimates, the model accounts for 21.2% of the variance in patients’ perceptions of their quality of life, 31.2% of the variance in the existence of financial stress as one of the top three stressors, 55.5% of the variance in the latent depression construct, and 52.5% of the variance in patients’ self-assessed mental health status – all having p <0.001. This model provided substantially better fit to the observed data than did the analogous model with anxiety symptoms as the mediator, having p-value for the χ2 test of fit = 0.2529.

Experiencing financial stress also had a direct effect on symptoms of depression (β = 0.048, p=0.048), though an impact substantially weaker than on anxiety (Figure 1B). The direct, indirect, and total effects of predictors on financial stress, quality of life, mental health, as estimated by the model, are detailed in Table 3 for anxiety and Table 4 for depression. We also explored an approach to the path model in which anxiety or depression led to financial stress, with feedback from financial stress to anxiety or depression. Neither of these approaches fit the data acceptably (see eSupplement).

Table 3.

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects on Patients’ Anxiety Symptoms and Global Mental Health

| Outcome | Predictor | Indirect | Direct | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Through | β | p | β | p | β | p | ||

| Mental health | Age | Young children, $ stress, & anxiety | 0.002 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.029 | ||

| Female | $ comfortable & QOL | −0.076 | 0.044 | |||||

| $ stress & anxiety | −0.060 | 0.049 | ||||||

| $ comfortable, QOL, & anxiety | −0.023 | 0.060 | ||||||

| $ comfortable, $ stress, & anxiety | −0.020 | 0.098 | ||||||

| TOTAL | −0.179 | 0.008 | −0.179 | 0.008 | ||||

| Children < age 10 | $ stress & anxiety | −0.042 | 0.034 | −0.042 | 0.034 | |||

| $ comfortable | QOL | 0.165 | 0.001 | |||||

| QOL & anxiety | 0.051 | 0.004 | ||||||

| $ stress & anxiety | 0.043 | 0.022 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 0.259 | <0.001 | 0.259 | <0.001 | ||||

| $ stress | Anxiety | −0.116 | 0.003 | −0.116 | 0.003 | |||

| Social support | QOL | 0.301 | <0.001 | |||||

| QOL & anxiety | 0.093 | <0.001 | ||||||

| $ stress & anxiety | 0.035 | 0.009 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 0.430 | <0.001 | 0.430 | <0.001 | ||||

| QOL | Anxiety | 0.200 | <0.001 | 0.645 | <0.001 | 0.845 | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety | −0.446 | <0.001 | −0.446 | <0.001 | ||||

| Anxiety | Age | Children <10 & $ stress | −0.006 | 0.017 | −0.006 | 0.017 | ||

| Female | $ stress | 0.134 | 0.040 | |||||

| $ comfortable & QOL | 0.053 | 0.059 | ||||||

| $ comfortable & $ stress | 0.044 | 0.077 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 0.231 | 0.009 | 0.231 | 0.009 | ||||

| Children < age 10 | $ stress | 0.094 | 0.019 | 0.094 | 0.019 | |||

| $ comfortable | QOL | −0.114 | 0.003 | |||||

| $ stress | −0.096 | 0.008 | ||||||

| TOTAL | −0.210 | <0.001 | −0.210 | <0.001 | ||||

| $ stress | 0.260 | <0.001 | 0.260 | <0.001 | ||||

| Social support | QOL | −0.209 | <0.001 | |||||

| $ stress | −0.079 | 0.003 | ||||||

| TOTAL | −0.288 | <0.001 | −0.288 | <0.001 | ||||

| QOL | −0.448 | <0.001 | −0.448 | <0.001 | ||||

| Quality of life | Female | $ comfortable | −0.118 | 0.043 | −0.118 | 0.043 | ||

| $ comfortable | 0.255 | <0.001 | 0.255 | <0.001 | ||||

| Social support | 0.466 | <0.001 | 0.466 | <0.001 | ||||

| Financial stress | Age | Children < age 10 | −0.021 | 0.012 | −0.021 | 0.012 | ||

| Female | $ comfortable | 0.170 | 0.043 | 0.515 | 0.009 | 0.685 | 0.001 | |

| Children < age 10 | 0.362 | 0.009 | 0.362 | 0.009 | ||||

| $ comfortable | −0.368 | <0.001 | −0.368 | <0.001 | ||||

$ = financially or financial; QOL = quality of life

Table 4.

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects on Patients’ Depression Symptoms and Global Mental Health

| Outcome | Predictor | Indirect | Direct | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Through | β | p | β | p | β | p | ||

| Mental health | Age | Young children, $ stress & depression | 0.002 | 0.121 | 0.002 | 0.121 | ||

| Female | $ comfortable & QOL | −0.050 | 0.068 | |||||

| $ stress & depression | −0.036 | 0.159 | ||||||

| $ comfortable, QOL, & depression | −0.043 | 0.084 | ||||||

| $ comfortable, $ stress, & depression | −0.012 | 0.194 | ||||||

| TOTAL | −0.140 | 0.022 | −0.140 | 0.022 | ||||

| Children < age 10 | $ stress & depression | −0.030 | 0.122 | −0.030 | 0.122 | |||

| $ comfortable | QOL | 0.116 | 0.003 | |||||

| QOL & depression | 0.099 | 0.006 | ||||||

| $ stress & depression | 0.027 | 0.101 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 0.242 | <0.001 | 0.242 | <0.001 | ||||

| $ stress | depression | −0.084 | 0.065 | −0.084 | 0.065 | |||

| Social support | QOL | 0.203 | <0.001 | |||||

| QOL & depression | 0.174 | <0.001 | ||||||

| $ stress & depression | 0.022 | 0.084 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 0.399 | <0.001 | 0.399 | <0.001 | ||||

| QOL | depression | 0.387 | <0.001 | 0.451 | <0.001 | 0.838 | <0.001 | |

| Depression | −0.712 | <0.001 | −0.712 | <0.001 | ||||

| Depression | Age | Children <10 & $ stress | −0.002 | 0.107 | −0.002 | 0.107 | ||

| Female | $ stress | 0.050 | 0.134 | |||||

| $ comfortable & QOL | 0.060 | 0.071 | ||||||

| $ comfortable & $ stress | 0.017 | 0.176 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 0.127 | 0.025 | 0.127 | 0.025 | ||||

| Children < age 10 | $ stress | 0.042 | 0.103 | 0.042 | 0.103 | |||

| $ comfortable | QOL | −0.139 | 0.002 | |||||

| $ stress | −0.038 | 0.078 | ||||||

| TOTAL | −0.178 | <0.001 | −0.178 | <0.001 | ||||

| $ stress | 0.118 | 0.048 | 0.118 | 0.048 | ||||

| Social support | QOL | −0.245 | <0.001 | |||||

| $ stress | −0.031 | 0.071 | ||||||

| TOTAL | −0.276 | <0.001 | −0.276 | <0.001 | ||||

| QOL | −0.544 | <0.001 | −0.544 | <0.001 | ||||

| Quality of life | Female | $ comfortable | −0.111 | 0.062 | −0.111 | 0.062 | ||

| $ comfortable | 0.256 | 0.001 | 0.256 | 0.001 | ||||

| Social support | 0.451 | <0.001 | 0.451 | <0.001 | ||||

| Financial stress | Age | Children < age 10 | −0.018 | 0.010 | −0.018 | 0.010 | ||

| Female | $ comfortable | 0.140 | 0.065 | 0.422 | 0.022 | 0.563 | 0.003 | |

| Children < age 10 | 0.356 | 0.004 | 0.356 | 0.004 | ||||

| $ comfortable | −0.325 | <0.001 | −0.325 | <0.001 | ||||

$ = financially or financial; QOL = quality of life

Discussion

Because critical illness is both common and associated with a substantial burden of psychological distress that impairs quality of life (1, 3, 4), identifying novel factors associated with distress could inform approaches to broadly improving long-term ICU survivorship. Our main findings demonstrated that: 1) the proportion of both patients and family members reporting financial stress remains high after discharge; 2) for patients, self-reported financial stress was significantly associated with female gender, children < age 10 and lower baseline level of comfort when paying bills; whereas insurance status, education, employment status, ICU length of stay and Apache II score were not; and 3) experiencing financial stress was both directly and indirectly associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as decreased global mental health. Our findings highlight the important consequences of the high prevalence and persistence of financial stress among ICU survivors and their family members and extend findings from past work that employed family, not patient, reports of financial burden (26).

Our finding that patients’ financial stress continued to increase throughout follow up after ICU discharge may indicate a causal link with the critical illness. This trend may be attributed, in part, to delays in the need to address costs of care. Bills may not yet have been received, and patients may have resources such as paid sick leave or FMLA (Family Medical Leave Act) time to use. However, over time and based on the degree of disability, job earnings may decrease (or disappear) as hospital bills start to increase. One prior study evaluating previously employed patients who survived critical illness found that nearly half had new unemployment at 12-month follow-up (24). Similarly, in a multi-center longitudinal study, nearly one-half of previously employed survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were jobless 12 months later, and over the 12-month follow-up, 70% accrued lost earnings averaging 60% of pre-ARDS annual earnings (22). At 5-year follow-up, nearly one-third never returned to work (23). From our data, we cannot determine the peak point of distress since it was still rising at the last time-period assessed (6 months), however, these studies suggest that financial stress likely persists for many survivors for an extended period of time after critical illness. By contrast, family members’ financial stress trend was curvilinear, suggesting that financial burdens are greatest around 3 months after a loved one is discharged from the hospital.

The trajectories of financial stress that our data show have important implications for the optimal timing of interventions that may help to alleviate some of this stress. For example, peer support groups are emerging as a novel way of improving post-ICU recovery for survivors and their family members, as well as accelerating the progress of knowledge about what to expect post critical illness (27). Financial counseling, typically provided during hospitalization, may in fact be more helpful after discharge.

Current research on financial “toxicity”, a term used to describe the harmful financial side effects of treatment (28), remains limited primarily to patients with cancer. Key components of financial toxicity include both objective financial burden (i.e. out-of-pocket costs) and subjective financial distress (i.e. perception of financial hardship) (29, 30). Among patients with cancer, financial toxicity is strongly correlated with health-related quality of life, indicating that financial toxicity is indeed a clinically relevant patient-centered outcome (21). Furthermore, in the cancer population, financial toxicity has been linked to symptom burden (31), adherence to treatment (32), and even survival (33). These are all outcomes of great importance for survivors of critical illness, including acute respiratory failure, and warrant future investigation.

Employment status, race, and household income have been shown to be associated with higher degrees of financial distress in patients with advanced cancer (21). However, our results did not show such associations, suggesting that the “subjective” feeling of financial stress may operate independently from “objective” measures of financial distress. Furthermore, these findings support the hypothesis that financial concerns affect patients and family members of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, and that patients surviving acute critical illness may have different drivers of financial stress than patients with more predictable conditions such as cancer. Additionally, we hypothesized that severity of illness measures such as ICU length of stay and Apache II scores would result in higher costs and disability, thus also serving as predictors of financial stress. We did not find these associations in our data, suggesting that clinical measures may not help in predicting who experiences financial stress.

Our findings that age, gender, and children at home < 10 years old were significant predictors of reporting financial stress suggest that younger patients with responsibilities for childrearing may suffer more from finance-related stress. This is in line with literature suggesting that hospital admissions have a greater economic impact on non-elderly patients (34).

Lastly, we found strong associations between financial stress and anxiety and depression, and both anxiety and depression were mediators for reduced global mental health. Our finding that the presence of social support significantly improved quality of life and decreased the extent to which financial concerns were important stressors for patients suggests that interventions targeted at improving support systems for these patients and their family members in and after an ICU stay may provide benefit and require additional research. Furthermore, future investigation into financial stress as a relevant and potentially modifiable patient-centered outcome in survivors of acute respiratory failure is needed. Reducing the stress associated with financial difficulties is a separate issue from relieving the actual financial burden, with the former being potentially modifiable by the healthcare system.

Our study has several important limitations. First, although participants were drawn from a large clinical trial representing geographically diverse sites, generalizability of our findings to smaller medical centers may be limited. Second, because financial stress was determined by a free text survey item, its prevalence may be underestimated (35). Third, future prospective studies are needed to better understand the specific causes of financial stress (i.e. lost wages, out-of-pocket costs, etc) that this study was not designed to answer. Fourth, the family member sample was too small to build a stable multi-predictor model. Last, while the increasing prevalence of financial stress over time suggests it may be causally linked to the critical illness, the lack of a non-critically ill comparison group does not permit a clear understanding of this relationship.

In conclusion, financial stress among patients after critical illness in the U.S. is common, persistent, and associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. Understanding risk factors and causes can help guide the development of novel interventions, such as post-ICU support groups and financial counselors, that may reduce the financial stress critically ill patients, including those with acute respiratory failure, and their family members face.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (K12HS022982). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AHRQ. This research was made possible by Grant Number 195 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of PCORI.

Footnotes

Institution(s) where the work was performed: Duke Medical Center, Duke Regional Hospital, University of Washington (Harborview Medical Center), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, UPMC Presbyterian Hospital

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Khandelwal, Downey, and Engelberg’s institutions received funding from Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. Drs. Khandelwal, Carson, Jones, Key, and Porter’s institution received funding from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).Drs. Hough and Reagan’s institutions received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Hough, Reagan, and Curtis received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Engelberg disclosed work for hire. Dr. Key received support for article research from PCORI. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, et al. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(6):1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation use in the United States. Critical care medicine. 2010;38(10):1947–1953. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ef4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Critical care medicine. 2012;40(2):618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Critical care medicine. 2012;40(2):502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Critical care medicine. 2001;29(10):1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schelling G, Stoll C, Haller M, et al. Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical care medicine. 1998;26(4):651–659. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Im K, Belle SH, Schulz R, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of caregiving after prolonged (> or =48 hours) mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest. 2004;125(2):597–606. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas SL, Daly BJ. Caregivers of long-term ventilator patients: physical and psychological outcomes. Chest. 2003;123(4):1073–1081. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, et al. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive care medicine. 2009;35(5):796–809. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davydow DS, Desai SV, Needham DM, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70(4):512–519. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox CE, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, et al. Expectations and outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Critical care medicine. 2009;37(11):2888–2894. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ab86ed. quiz 2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, et al. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care. 2016;20:16. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients’ families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(23):1839–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.23.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shankaran V, Ramsey S. Addressing the Financial Burden of Cancer Treatment: From Copay to Can’t Pay. JAMA oncology. 2015;1(3):273–274. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, et al. Financial Distress and Its Associations With Physical and Emotional Symptoms and Quality of Life Among Advanced Cancer Patients. The oncologist. 2015;20(9):1092–1098. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox CE, Hough CL, Carson SS, et al. Effects of a Telephone- and Web-based Coping Skills Training Program Compared with an Education Program for Survivors of Critical Illness and Their Family Members. A Randomized Clinical Trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018;197(1):66–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201704-0720OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2009;18(7):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2017;123(3):476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamdar BB, Huang M, Dinglas VD, et al. Joblessness and Lost Earnings after Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in a 1-Year National Multicenter Study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2017;196(8):1012–1020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201611-2327OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamdar BB, Sepulveda KA, Chong A, et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax. 2017 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman BC, Jackson JC, Graves JA, et al. Employment Outcomes After Critical Illness: An Analysis of the Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors Cohort. Critical care medicine. 2016;44(11):2003–2009. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) The SUPPORT Principal Investigators JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274(20):1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikkelsen ME, Jackson JC, Hopkins RO, et al. Peer Support as a Novel Strategy to Mitigate Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. AACN advanced critical care. 2016;27(2):221–229. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2016667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zafar SY. Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care: It’s Time to Intervene. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2016;108(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2013;27(2):80–81. 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanratty B, Holland P, Jacoby A, et al. Financial stress and strain associated with terminal cancer--a review of the evidence. Palliative medicine. 2007;21(7):595–607. doi: 10.1177/0269216307082476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of Financial Strain With Symptom Burden and Quality of Life for Patients With Lung or Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(15):1732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association Between Prescription Co-Payment Amount and Compliance With Adjuvant Hormonal Therapy in Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(18):2534–2542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(9):980. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobkin CFA, Kluender R, et al. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2016. The Economic Consequences of Hospital Admissions. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tourangeau RRL, Rasinski K. The Psychology of Survey Response. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.