Manuscript Text

We report a case of an individual exposed to HIV around the time of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation where detection of HIV-1 RNA and initial diagnosis were delayed. PrEP has the potential to alter the detection of biomarkers of early and acute infection leading to potential confusion in interpretation of HIV status and delayed treatment of similar cases in settings where PrEP is delivered.

A 31-year-old male presented to a New York City Department of Health clinic for PrEP assessment. A 3rd generation rapid HIV and pooled nucleic acid amplification (NAAT) tests were negative at that time. Seven days later the patient was seen in the HIV Prevention Program Clinic based in the community and affiliated with New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia Medical Center, and reported multiple male sexual partners including known HIV positive partners in the last 3 months and inconsistent condom use. The patient was started on tenofovir-emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) at this visit and was given a 30-day supply. A 4th generation HIV test (Abbott Architect Ag/Ab Combo), gonorrhea and chlamydia from three sites, syphilis, and hepatitis (A, B, C) were negative.

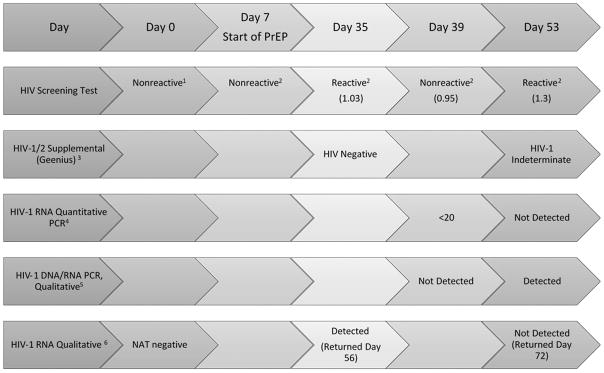

Twenty-eight days later the patient returned to the clinic, reporting 100% TDF/FTC adherence. At that time, Abbott HIV Ag/Ab was reactive with a signal to cutoff ratio (s/co) of 1.03 (Reactive >1.0). Supplemental testing was performed with the Geenius™ HIV1/2 Confirmatory Assay (Geenius, Bio-Rad, Marne la Coquette, France) and was negative (See Figure 1). A qualitative HIV-1 RNA test was sent to the New York State DOH (NYSDOH). These results prompted re-testing four days later at which point the Abbott Combo s/co was 0.95, interpreted as “negative,” as was a qualitative DNA/RNA PCR (COBAS-Qualitative, AmpliPrep/TaqMan HIV-1 Qual Test). The virus was detected, however, using a quantitative test, COBAS AmpliPrep/TaqMan HIV-1 Test kit, with HIV-1 RNA level below the lower limit of detection (<20 copies/mL). At this point, Dolutegravir was added to the regimen.

Figure 1. Timeline of HIV Diagnostics for Patient Initiating PrEP.

1 OraQuick® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test, Orasure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA

2 Abbott Architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA

3 Geenius, Bio-Rad, Marne la Coquette, France

4 COBAS AmpliPrep/TaqMan HIV-1 Test kit, version 2.0, Indianapolis, IN, USA

5 COBAS AmpliPrep/TaqMan HIV-1 Qual Test, Indianapolis, IN, USA

6 APTIMA HIV-1 RNA qualitative assay, Hologic, Inc., San Diego, CA

HIV testing was repeated two weeks later. Abbott Combo was reactive (s/co = 1.3), Geenius was indeterminate (positive for gp41 only), COBAS-Quantitative was not detected. However, COBAS-Qualitative was positive. The initial qualitative HIV-1 RNA from day 28 post-PrEP initiation ultimately returned positive. The patient was switched to a once-daily fixed-dose combination antiretroviral regimen and continues to have an undetectable HIV-1 RNA level. A GenoSure archive (GenoSure, Monogram Biosciences, San Francisco, California, USA) returned with insufficient HIV infected cells or cell-associated DNA targets to amplify the virus for assessment of mutations.

PrEP is an important tool in efforts to end the HIV epidemic. Recommendations for PrEP care include HIV testing every three months. The current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) HIV testing algorithm recommends an initial 4th generation HIV Antigen/Antibody (Ag/Ab) combination immunoassay; followed by HIV 1/2 differentiation immunoassay if positive and a NAAT if the immunoassay is indeterminate or inconclusive.1 To date, a comprehensive evaluation of how PrEP could impact diagnosis of acute and early HIV infection has not been fully completed. It also remains to be determined what are optimal ways of discussing and counseling patients about HIV status and timing of infection while on PrEP.

The Fiebig stage-classification system is used to characterize the progression from exposure to HIV through HIV seroconversion and utilizes HIV-1 RNA, p24 antigen, 3rd generation enzyme immunoassay, 2nd generation EIA and Western Blot to categorize acute and early HIV infection into six stages.2 Typically, in acute HIV, viral RNA levels peak at over 105 copies/mL at 7–10 days, falling 2–3 log during seroconversion, and before reaching a steady state in 30–50 days.3 Newer HIV diagnostic assays take advantage of the p24 positivity that occurs with the rise in viral load seen in stage II and early HIV antibodies seen in stage III. These assays have improved sensitivity for detection of early infection and shorten the interval between the time of infection and initial immunoassay reactivity. Their performance in the context of PrEP, however, remains to be determined.

One commonly used 4th generation HIV test is the Abbott Combo, a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay. The platform measures the relative light units for which a relationship exists between the amount of HIV antigen and antibodies in the sample, and the result is determined by comparing the chemiluminescent signal in the reaction to a cutoff signal. Samples with a signal to the cutoff ratio (s/co) greater than 1.0 are considered reactive. In a non-human primate model of breakthrough SIV infection, the macaques who became infected while receiving PrEP had lower peak viral loads and delayed antibody maturation but not the timing of seroconversion.4 In the HPTN/ADAPT study 50% of patients with acute infection at the first visit had a viral load below the limit of quantification, and in cases where PrEP was continued for 3–4 months after infection, RNA levels dropped below the level of detection, and s/co ratios were low.5

In the Partner’s PrEP study, the authors evaluated the progression of Fiebig stages in seroconverters and found that individuals taking PrEP had HIV-1 RNA levels about 3/4 log lower, 11% had undetectable RNA, and no differences in the Abbott Combo s/co ratios.6 However, PrEP delayed the time to detection of seroconversion, and a consistent trend of delayed Fiebig stage progression was noted among seroconverters believed to be taking PrEP.6

The s/co ratio is known to be lower for viral loads less than 10,000 copies/mL making it a less reliable test for identifying acute HIV in individuals on treatment. In low prevalence settings, studies have evaluated raising the s/co to increase specificity and positive predictive value without compromising sensitivity.7 Theoretically, in high prevalence settings and in the context of viral suppression one could consider lowering the cutoff to increase sensitivity. Further complicating the HIV testing algorithm is evidence that early ART may lead to undetectable DNA levels by current commercially available assays. The HIV DNA set-point is established early in acute HIV infection as individuals started on early antiretroviral therapy (ART) had a significantly lower HIV DNA levels. 8 In an individual with acute HIV but with viral suppression on PrEP there may be a failure to detect HIV DNA.8 Additionally new data has demonstrated that the initiation of ART during acute HIV may lead to HIV specific antibodies failing to develop or decline after initiation of antiretrovirals.9

Several studies have shown that patients who acquire HIV while adherent to PrEP can have low or undetectable viral loads.10,11 Suppression of the viral load could plausibly result in false negative results during Fiebig stages II and III. PrEP thus has the potential to alter the natural history of disease-causing a failure of the current testing algorithm. While this case most likely does not represent a failure of PrEP given the patient’s exposures prior to and in the first week after PrEP initiation before optimal drug levels could be achieved, there have been three well-publicized cases of individuals acquiring HIV while on PrEP. 10–12 In the Toronto case, the patient had significant transmitted resistance and the current algorithm was suitable for making the diagnosis.12 In the New York case, the patient was initially positive via Abbott Combo testing and qualitative NAA. However, two quantitative PCRs were undetectable, and the confirmatory assay remained non-reactive after five weeks.11 In the Amsterdam PrEP study, a patient acquired wild-type HIV in spite of confirmed adherence to PrEP. The patient was HIV antibody positive, but antigen negative. The HIV RNA was negative (<50 copies/mL), the western blot showed only antibodies to p160 viral antigen and combined DNA/RNA testing was negative.10

Current guidelines for individuals taking PrEP recommend HIV testing every three months along with assessment for signs and symptoms of acute HIV but provide no guidance on optimal screening for and management of acute/early infection specifically amongst individuals on PrEP.13 The challenge of screening with current algorithms is highlighted by the statement from the Association of Public Health Laboratories conceding that, “there is insufficient data regarding the performance of the algorithm and any potential effects of pre-exposure prophylaxis”.14 And thus further research is needed to assess the performance of current testing algorithms in individuals initating PrEP as well as those taking it consistently or intermittantly during “periods of risk”. For example, questions that warrant further exploration in individuals initiating or taking PrEP include assessing s/co ratios that may prompt further testing or use of qualitative RNA testing earlier in the testign algorithm. Areas rich for further investigation in this context include assessing optimal screening strategies to pick up incident infections and exploring the role of novel biomarkers to detect early and acute infecition. Given the potential of PrEP to cause a delay in the evolution of antibodies or delayed detection of the nucleic acid signal, this can lead to delays in confirmation of infection which has implications for counseling of patients about their HIV status and decisions about treatment of such individuals. And thus careful assessment of optimal HIV testing algorithms for individuals receiving PrEP is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Dr. Zucker is supported by the training grant “Training in Pediatric Infectious Diseases” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health [T32AI007531]. Dr. Gordon is a recipient of a Gilead FOCUS grant to address barriers to HCV screening and linkage to care.

Contributor Information

Jason Zucker, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Divisions of Infectious Diseases, Departments of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Caroline Carnevale, Principal Investigator HIV Prevention Program, New York Presbyterian Hospital’s Comprehensive Health Center.

Alex J. Rai, Associate Professor, Director of the Special Chemistry Laboratory, Department of Pathology & Cell Biology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Peter Gordon, Assistant Professor, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Magdalena E. Sobieszczyk, Associate Professor, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Branson BM, Owen SM, Wesolowski LG, et al. Quick Reference Guide—Laboratory Testing for the Diagnosis of HIV Infection: Updated Recommendations Recommended Laboratory HIV Testing Algorithm for Serum or Plasma Specimens. 2014 Apr;(2014):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiebig E, Wright D, Rawal B, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. Aids. 2003 Mar;17:1871–1879. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000076308.76477.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busch MP, Satten GA. Time course of viremia and antibody seroconversion following human immunodeficiency virus exposure. Am J Med. 1997;102(5 B):117–124. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis KA, Kennedy MS, Luckay A, et al. Delayed Maturation of Antibody Avidity but Not Seroconversion in Rhesus Macaques Infected With Simian HIV During Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(5):355–362. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182234a51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivay MV, Li M, Piwowar-Manning E, et al. Characterization of HIV seroconverters in a TDF/FTC PrEP study. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(3):1. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnell D, Ramos E, Celum C, et al. The Effect of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis on the Progression of HIV-1 Seroconversion. Aids. 2017;0:1. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen TO, Robertson P, Whybin R, et al. A signal-to-cutoff ratio in the abbott architect HIV Ag/Ab combo assay that predicts subsequent confirmation of HIV-1 infection in a low-prevalence setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(5):1709–1711. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03583-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananworanich J, Chomont N, Eller LA, et al. HIV DNA Set Point is Rapidly Established in Acute HIV Infection and Dramatically Reduced by Early ART. EBioMedicine. 2016;11:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Souza MS, Pinyakorn S, Akapirat S, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy during acute HIV-1 infection leads to a high rate of nonreactive HIV serology. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):555–561. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoornenborg E, Prins M, Achterbergh RCA, et al. Acquisition of wild-type HIV-1 infection in a patient on pre-exposure prophylaxis with high intracellular concentrations of tenofovir diphosphate: a case report. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(11):e522–e528. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markowitz M, Grossman H, Anderson PL, et al. Newly Acquired Infection with Multi-Drug Resistant HIV-1 in a Patient Adherent to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017:1. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson P, Harrigan PR, Tan D. Multidrug-Resistant HIV-1 Infection despite Preexposure Prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):500–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1615253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 24, 2016];Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States – 2014 Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf.

- 14.Association of Public Health Laboratories. Suggested Reporting Language for the Diagnostic Testing Algorithm. 2017 Apr; https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID_2017Apr-HIV-Lab-Test-Suggested-Reporting-Language.pdf.