Abstract

Acute alcohol intoxication induces significant alterations in brain cytokines. Since stress challenges also profoundly impact central cytokine expression, these experiments examined the influence of acute and chronic stress on ethanol-induced brain cytokine responses. In Experiment 1, adult male rats were exposed to acute footshock. After a post-stress recovery interval of 0, 2, 4, or 24 h, rats were administered ethanol (4 g/kg; intragastric), with trunk blood and brains collected 3 h later. In non-stressed controls, acute ethanol increased expression of Il-6 and IκBα in the hippocampus. In contrast, rats exposed to footshock 24 h prior to ethanol demonstrated potentiation of hippocampal Il-6 and IκBα expression relative to ethanol-exposed non-stressed controls. Experiment 2 subsequently examined the effects of chronic stress on ethanol-related cytokine expression. Following a novel chronic escalating stress procedure, rats were intubated with ethanol. As expected, acute ethanol increased Il-6 expression in all structures examined, yet the Il-6 response was attenuated exclusively in the hippocampus in chronically stressed rats. Later experiments determined that neither acute nor chronic stress affected ethanol pharmacokinetics. When ethanol hypnosis was examined, however, rats exposed to chronic stress awoke at significantly lower blood ethanol levels compared to acutely stressed rats, despite similar durations of ethanol-induced sedation. These data indicate that chronic stress may increase sensitivity to ethanol hypnosis. Together, these experiments demonstrate an intriguing interaction between recent stress history and ethanol-induced increases in hippocampal Il-6, and may provide insight into novel pharmacotherapeutic targets for prevention and treatment of alcohol-related health outcomes based on stress susceptibility.

Keywords: Rat, Ethanol, Acute Stress, Chronic Stress, Cytokines, Hippocampus, Hypnosis

1. Introduction

Stress can have a profound impact on quality of life, with stressful life experiences implicated in the onset and progression of many physiological and psychological diseases including, but not limited to, cardiac disease (e.g., Dimsdale, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2012), type II diabetes (Kelly and Ismail, 2015), obesity (Adam and Epel, 2007; De Vriendt et al., 2009; Foss and Dyrstad, 2011), chronic inflammatory diseases (e.g., psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis; Affleck et al., 1997; Verhoeven et al., 2009), visceral pain disorders (Moloney et al., 2016), anxiety (Faravelli et al., 2012), depression (Hammen, 2005; Mazure et al., 2000), and drug and alcohol dependence (Blaine and Sinha, 2017; Lemieux and al'Absi, 2016; Piazza and Le Moal, 1996). The mechanisms by which stress impacts physiological and psychological well-being continue to be intensely investigated. More recently, research has identified stress-induced activation of neuroimmune processes as a common pathway by which stress may impart deleterious consequences on health (for reviews see Kubera et al., 2011; Maes et al., 2009). For instance, stress exposure in and of itself has been shown to result in increased expression of inflammatory related factors in the brain (e.g., Deak et al., 2015; Rossetti et al., 2016), with the hypothalamus (Blandino et al., 2009; Deak et al., 2005b; Girotti et al., 2013; Grippo et al., 2005), hippocampus (Goshen et al., 2008; Rossetti et al., 2016; You et al., 2011), and cortex (Rossetti et al., 2016; You et al., 2011) all exhibiting sensitivity to these stress-induced changes. Additionally, it has been well-established that certain stressors can lead to changes in emotion-related behaviors, including increased expression of depressive-like behavior in preclinical models (Feng et al., 2012; Vitale et al., 2009; for review see Willner, 2005; Wu et al., 2012). Importantly, blockade of stress-related activation of neuroimmune processes via deletion or over-expression of inflammatory pathway genes (Goshen et al., 2008), or anti-inflammatory pharmacological agents (Karson et al., 2013; Santiago et al., 2014), has been shown to subsequently reverse depressive-like behavior, thus further implicating neuroimmune processes as a likely mechanism for these stress-related effects on negative affective behavior.

Historically, stress has also been shown to be an important contributor to many components of drug and alcohol addiction (for review see Goeders et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2003; Sinha et al., 2011; Stewart, 2003). In the case of alcohol use disorders, research has demonstrated that there is a very complicated and often reciprocal relationship between stress and alcohol use (Brady and Sonne, 1999; Pohorecky, 1991; Sillaber and Henniger, 2004; Sinha, 2012; Spanagel et al., 2014). Even when using more parsimonious animal models to explore the nature of this relationship, the impact of stress on alcohol consumption, responsiveness, and withdrawal (and vice versa) has been difficult to define, and some times contradictory (for review see Becker, 2012; Becker et al., 2011; Pohorecky, 1990). For example, while a variety of stressors including restraint (e.g., Lynch et al., 1999; Ploj et al., 2003), forced-swim (Fullgrabe et al., 2007; Siegmund et al., 2005) and footshock (Vengeliene et al., 2003; Volpicelli et al., 1990) have all been reported to increase ethanol consumption, in contrast, there are numerous reports of these same stressors decreasing ethanol consumption (Boyce-Rustay et al., 2008; Darnaudery et al., 2007; Ng Cheong Ton et al., 1983).

Even when moving beyond voluntary intake and examining the effects of forced ethanol exposure, the interaction between stress and alcohol remains quite complex. For instance, in some situations, exposure to an ethanol diet prior to a stress challenge has been shown to result in a dampened HPA1 axis response to the stressor (e.g., Lee and Rivier, 1993; Rivier, 1995). In contrast, our laboratory has reported an exacerbated HPA response to a stressor imposed during withdrawal from an earlier acute ethanol exposure (Buck et al., 2011), with similar stress sensitization reported during protracted withdrawal from long-term ethanol exposure (e.g., Valdez et al., 2003). On the other hand, stress history can influence later responsiveness to ethanol. Acute stress exposures—such as handling (Peris and Cunningham, 1986) and inescapable footshock (Drugan et al., 1996; Drugan et al., 2007)—have been shown to exacerbate behavioral sensitivity to acute ethanol challenge, with longer periods of stress exposure also having been reported to affect sensitivity to acute ethanol (Blakley and Pohorecky, 2006; Fernandez et al., 2016; Matsumoto et al., 1997; Pohorecky, 2006). It has also been observed that a history of repeated stress exposure sensitizes the development of ethanol-withdrawal-related anxiogenesis (Breese et al., 2004; Knapp et al., 2007). Regardless of the complexity of the relationship between stress and alcohol use/responsiveness, it is nevertheless clear that stress can significantly impact an organism’s response to ethanol, and that a history of ethanol exposure can alter how an organism reacts to stress.

The potential mechanisms by which these unique interactions take place have been extensively examined, and it is not surprising that the effects of stress on neuroimmune processes have emerged as likely contributors (Frank et al., 2011; Knapp et al., 2011). A multitude of independent studies have now demonstrated that ethanol alone is a stimulus that is sufficient to induce significant changes in neuroimmune factors, even in the absence of an immune challenge. In humans, for example, several plasma cytokines were observed to be elevated during acute ethanol withdrawal (Gonzalez-Quintela et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2003). Significant increases in chemokines and microglial markers were also observed across several structures when the brains of alcoholics were examined post mortem (He and Crews, 2008). In animal models, chronic ethanol exposure has been shown to significantly elevate mRNA expression of a variety of cytokines in the brain, including Il2-1β, Il-6, Tnf-α3, and Mcp-14 in both rats (Tiwari et al., 2009; Valles et al., 2004) and mice (Alfonso-Loeches et al., 2010; Kane et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2008). Furthermore, manipulation of neuroimmune factors altered a variety of ethanol-related behaviors, including ethanol intake and preference (Agrawal et al., 2011; Blednov et al., 2011; Blednov et al., 2012; Marshall et al., 2016) and ethanol-induced sedation and motor impairment (Wu et al., 2011). Within our own laboratory, we have demonstrated that acute ethanol intoxication consistently stimulates increased expression of Il-6 and IkBa5 in several brain regions, including hippocampus, amygdala, and the PVN6 (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015). In contrast, in these same experiments, expression of other cytokines, including Il-1β and Tnf-α, was consistently suppressed during acute ethanol intoxication. These highly reproducible, intoxication-related changes in neuroimmune genes have been termed ethanol-induced “Rapid Alterations in Neuroimmune Gene Expression” (RANGE) effects (Gano et al., 2016). Importantly, these RANGE effects vary in magnitude based on the age of ethanol exposure (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015), and show remarkable plasticity across the first few ethanol exposures depending upon the schedule of ethanol delivery (Gano et al., 2016).

Given that both stress and ethanol exposures result in dramatic alterations in neuroimmune processes, the goal of the current studies was to examine the effects of acute and chronic stress on the subsequent neuroimmune response to an acute ethanol challenge. We began, in Experiment 1, by first investigating the influence of an acute stressor—footshock—on a previously characterized, and highly reproducible, ethanol-induced pattern of alterations in brain cytokines (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015). Footshock was chosen for the stressor, as our laboratory has extensively studied the effects of acute footshock on central expression of several cytokines, as well as other inflammatory-related factors, across multiple brain regions and time points (e.g., Blandino et al., 2009; Deak et al., 2005b; Hueston et al., 2011). After observing that acute footshock potentiated ethanol’s effects on central expression of Il-6 and IκBα in hippocampus, Experiment 2 then examined whether a chronic, and escalating in nature, stress regimen (with footshock as the final stress challenge) would differentially impact the subsequent response to acute ethanol challenge (Lovelock et al., in prep). Indeed, results from Experiment 2 demonstrated that chronic stress actually diminished acute ethanol-induced elevations in hippocampal Il-6—a result that was opposite to the effects of acute stress. In order to address if these differential consequences of acute versus chronic stress on ethanol-related alterations in brain cytokine expression might impact pharmacokinetic and behavioral responses to acute ethanol, Experiments 3 and 4 assessed blood ethanol content, corticosterone, and ethanol-induced sleep time in response to an acute ethanol challenge in rats with a history of acute or chronic stress.

2. Methods

2.1 General Methods

2.1.1 Subjects

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (~300 g) were purchased from Harlan (Frederick, MD) and acclimated to the colony for at least 2 weeks prior to experimentation. Colony conditions were maintained at 22 ± 1°C with a 12 hr light–dark cycle (lights on 0700 hr). Animals were pair-housed in standard Plexiglas bins and given ad libitum access to food and water, with wooden chew blocks also provided as a form of enrichment. In all experiments, cage-mates were exposed to the same stress and drug-exposure condition, and rats were handled for 3–5 min for 2 days preceding the start of the experiment. Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Binghamton University, and at all times animals were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s guidelines for animal care (NIH Publication No.: 80–23; Institute of Laboratory Animal Research, 1996).

2.1.2 Stress Procedures

2.1.2.1 Restraint

Rats were transported to a separate experimental room and placed in Plexiglas tubes (6.35 cm dia, 21.59 cm length; Broome-style restrainer model no. 553-BSRR, Plas Labs, Inc., Lansing, MI) that had ample holes for ventilation. Restraint stress was applied for 1 h, and was devoid of any active immobilization, limb/tail tethering, or compression (Lovelock and Deak, 2017).

2.1.2.2 Forced Swim Challenge

The forced-swim stressor was administered according to procedures described in detail elsewhere (e.g., Deak et al., 2005a). Briefly, rats were transported to a separate experimental room and immediately placed in a Plexiglas cylinder (45 cm height; 20 cm dia) that was filled with water to a depth of 30 cm. Water temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C, with fresh water used for every subject. Rats were placed in the swim cylinders for 30 min, after which they were towel-dried and returned to the home cage.

2.1.2.3 Footshock paradigm

Rats were exposed to 80 inescapable footshocks (1.0 mA, 90 s variable inter-trial interval, 5 s each) over the course of approximately 120 min in standard rat footshock chambers [30.5 (L) × 26.5 (W) × 33 (H) cm; Habitest Chamber, Model H10-11R-TC-SF, Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA] (Buck et al., 2011; Hueston et al., 2011). The side walls of the chambers were constructed of stainless steel, except for the front doors, which were clear Plexiglas. The floors consisted of steel rods through which a scrambled shock from a shock generator was delivered (LABLINC Model H01-01, and Precision Animal Shocker Model H13-15, Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA). Each footshock apparatus was located within a sound-attenuating chamber that was illuminated by a 20-W white light bulb. Individual ventilation fans provided background noise for each chamber. Shock chambers and waste collection trays were thoroughly cleaned and dried between rats.

2.1.2.4 Chronic Escalating Distress—a novel model of chronic stress

This 11-day model (see Figure 1C) consisted of 3 distinct phases, with each subsequent phase representing an increase in the duration of stress exposure on a particular day, as well as an increase in overall stress intensity (Lovelock et al., in prep). During Phase 1, animals received 60 min of daily restraint for 5 consecutive days. In Phase 2, rats continued to receive 60 min of daily restraint, but with this restraint stress immediately followed by a 30 min forced-swim stress exposure. Similar to Phase 1, Phase 2 also lasted for a total of 5 days. Finally, Phase 3 was a single 2 h exposure to footshock (as described above), which provided the opportunity to examine the impact of chronic stress on ethanol responsivity following a stressor for which we’ve already extensively characterized its impact on brain cytokines (e.g., Buck et al., 2011; Catanzaro et al., 2014; Hueston and Deak, 2014). In this way, both the intensity and duration of daily stress challenges “escalated” across the 11-day stress period, with the final stress challenge (footshock) being a stressor for which we have published extensive data on cytokine regulation. A more detailed characterization of the CED7 model is currently in progress.

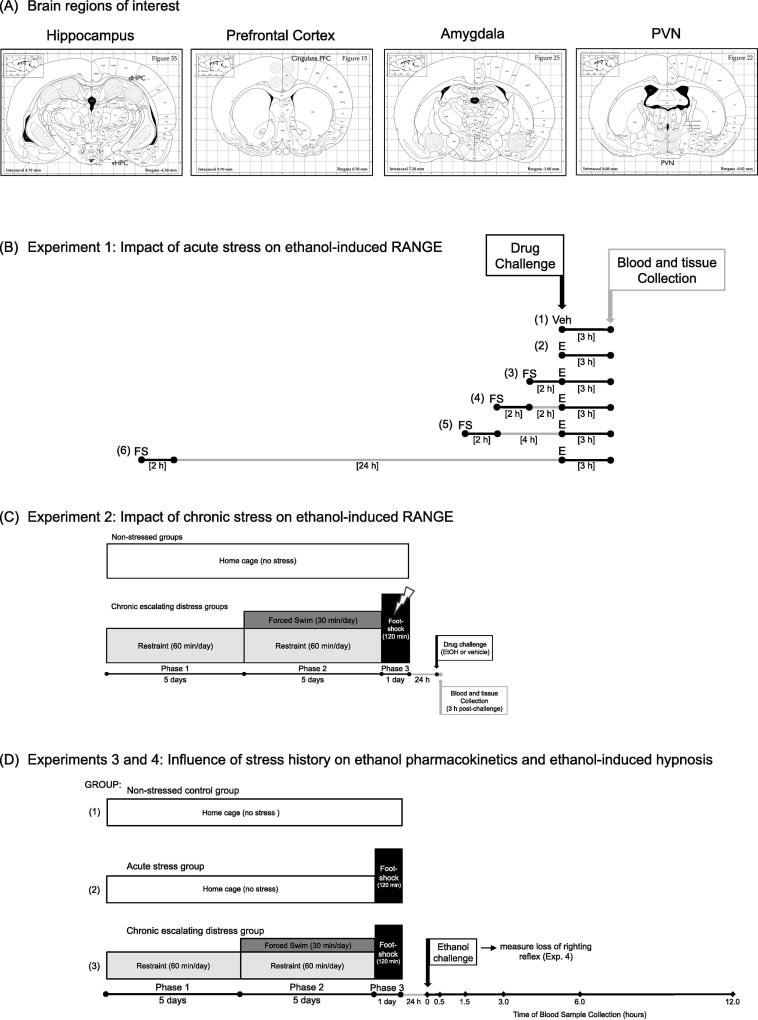

Figure 1.

Diagrams depicting collection of brain sites of interest, as well as study designs for Experiments 1–4. PANEL (A) Micropunches were taken based on the Paxinos and Watson (1998) rat brain atlas, with the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) collected in both Experiments 1 and 2. PANEL (B) Experiment 1: Acute stress procedure. In this experiment, two groups of rats were not exposed to stress, with one group challenged with (1) vehicle (Veh), and the other challenged with (2) 4 g/kg intragastric [i.g.] ethanol (E). All remaining experimental groups experienced an acute footshock (FS) exposure that was 2 h in duration, followed by an acute ethanol challenge either (3) immediately, (4) 2 h, (5) 4 h, or (6) 24 h after the end of footshock. Blood and brain samples were collected 3 h after vehicle or ethanol intubation. PANEL (C) Experiment 2: Chronic escalating distress procedure. Half of the rats in Experiment 2 were non-stress controls, and ultimately received either a vehicle or 4 g/kg i.g. ethanol (EtOH) intubation as their drug challenge. The remaining animals were exposed to chronic stress using our newly developed chronic escalating distress (CED) procedure. In phase 1 of this paradigm, rats were placed in restraint for 60 min per day for 5 consecutive days. During phase 2, animals again were exposed to 60 min of restraint per day, but with this restraint immediately followed by 30 min of forced-swim exposure. Phase 2 also lasted for 5 days. Finally, for phase 3, rats were given one 120-min acute footshock session, with drug challenge (EtOH or vehicle) administered 24 h after the conclusion of footshock. Blood and tissue were collected 3 h following drug intubation. PANEL (D) Experiment 3: Stress history and ethanol pharmacokinetics. All animals were given a 4 g/kg i.g. ethanol challenge, with tail blood samples collected immediately before (baseline; 0 h), as well as 0.5, 1.5, 3.0, 6.0, and 12.0 h after ethanol administration. (1) Non-stressed controls remained non-manipulated in the homecage during the stress phase of the experiment, and until the time of ethanol challenge. (2) Rats in this group were non-manipulated in the homecage for the first 10 days of the experiment, and were then exposed to acute (2 h) footshock on Day 11. Ethanol was delivered 24 h later. (3) Animals in this experimental condition were exposed to the full 11-day chronic escalating distress procedure described above, with ethanol administered 24 h after the final footshock stressor. In Experiment 4, a new group of rats were exposed to the same three experimental conditions and were then given a 4 g/kg intraperitoneal ethanol challenge in order to assess ethanol-induced hypnosis via the loss of righting reflex (LORR). Latency to LORR was recorded, as well as duration of LORR. Upon awakening, a single tailblood sample was collected for analysis of blood ethanol concentrations.

2.1.3 Ethanol Challenge

Ethanol (95%; VWR International, West Chester, PA) was freshly diluted on each morning of experimentation with either tap water to make a 20% (v/v) solution for intragastric (i.g.) administration for Experiments 1–3, or with sterile, pyrogen-free saline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration in Experiment 4. In Experiment 1, animals were intubated with ethanol either immediately (0 h), 2, 4, or 24 h following acute footshock. Non-stressed controls were challenged with ethanol or an isovolumetric amount of room temperature tap water. For Experiments 2, 3, and 4, animals were challenged with ethanol 24 h following termination of footshock on the final day of the chronic escalating distress procedure (day 11).

2.1.4 Plasma and tissue collection

Brains were harvested after rapid decapitation and trunk blood collected in EDTA9-coated glass blood collection tubes (BD Vacutainers, VWR cat. no. VT6450, Radnor, PA). Plasma was separated in a refrigerated centrifuge and was then frozen at −20 °C until time of assay. Whole brains were immediately flash frozen by brief submersion in cold isopentane that was maintained on dry ice. Frozen brains were stored at −80 °C and were later sliced in a cryostat maintained at −20 °C. Brain regions of interest (e.g., hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and PVN) were collected bilaterally using chilled micropunches (1.0–2.0 mm) according to the Paxinos and Watson (1998) rat brain atlas (see Figure 1A). Brain punches were stored at −80 °C until the time of RNA extraction.

2.1.5 RNA extraction and first strand synthesis

A Qiagen Tissue Lyser (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) provided rapid, thorough, and consist homogenization of brain samples. Each structure was placed into a 2.0 ml Eppendorf tube containing 500 µl of Trizol® RNA reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and a 5 mm stainless steel bead, and was then rapidly shaken for 2 min for complete disruption/homogenization of the tissue. Chloroform (100 µl) was then added to the Trizol solution, the samples briefly shaken, and then samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C. Equal volume of 70% ethanol was added to the supernatant and purified through RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Columns were washed with buffer and eluted with 30 µL of RNase-free water (65 °C). RNA yield and quality was determined using a Nanodrop micro-volume spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE), with total RNA stored at −80 °C until the time of cDNA synthesis. Synthesis of cDNA was performed on 0.1–1.0 µg of normalized total RNA from each sample using the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (Cat. No. 205313, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) which included a DNase treatment step. All cDNA was stored at −20 °C until time of assay.

2.1.6 Real-time RT-PCR

Probed cDNA amplification was performed in a 10 µL reaction consisting of 5 µL IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 170-8882, Hercules, CA), 0.5 µL primer (final concentration 250 nM), 0.5 µL cDNA template, and 4 µL Rnase-free water run in triplicate in a 384 well plate (BioRad, cat. no. HSP-3805) and captured in real-time using a PCR detection system (BioRad, model no. CFX384). Following a 3-min hot start (95 °C), samples underwent denaturation for 30 s at 95 °C, annealing for 30 s at 60 °C and extension for 30 s at 72 °C for 40 cycles. An additional denaturation (95 °C, 1 min) and annealing cycle (55 °C, 1 min) were conducted to ensure proper product alignment prior to melt curve analysis. For melt curve analysis, samples underwent 0.5 °C changes every 15 s ranging from 55 °C to 95 °C. A single peak expressed as the negative first derivative of the change in fluorescence as a function of temperature indicated primer specificity to the target gene. In all experiments, Gapdh10 was used as a reference gene, as studies from our laboratory have revealed more stable gene expression across ethanol treatment conditions with this gene (e.g., Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014). Primer sequences and a brief description of gene function can be found in Doremus-Fitzwater et al. (2015; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Ethanol and/or Stress-induced Changes in Gene Expression in Rats from Experiment 1

| Prefrontal Cortex | Amygdala | PVN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Il-6 | Non-stressed + Veh | 103.4 ± 10.1 | 102.6 ± 9.2 | 104.3 ± 11.0 |

| Non-stressed + EtOH | 114.5 ± 13.8 | 149.6 ± 11.0* | 121.6 ± 17.1 | |

| Stress + EtOH (0 h) | 160.1 ± 28.7 | 167.6 ± 17.5* | 134.1 ± 10.9 | |

| Stress + EtOH (2 h) | 152.0 ± 24.0 | 152.4 ± 13.8* | 124.5 ± 9.2 | |

| Stress + EtOH (4 h) | 137.2 ± 25.5 | 139.6 ± 9.8* | 122.6 ± 14.0 | |

| Stress + EtOH (24 h) | 142.1 ± 17.6 | 142.8 ± 7.3* | 121.5 ± 10.1 | |

|

| ||||

| IκBα | Non-stressed + Veh | 103.3 ± 10.8 | 101.5 ± 6.3 | 110.3 ± 17.6 |

| Non-stressed + EtOH | 181.6 ± 30.4 | 136.7 ± 18.6 | 188.1 ± 38.3 | |

| Stress + EtOH (0 h) | 140.3 ± 21.6 | 157.8 ± 27.0 | 185.5 ± 51.8 | |

| Stress + EtOH (2 h) | 179.3 ± 29.2 | 156.9 ± 27.6 | 91.8 ± 17.3 | |

| Stress + EtOH (4 h) | 125.2 ± 17.6 | 141.9 ± 30.5 | 201.8 ± 58.7 | |

| Stress + EtOH (24 h) | 152.1 ± 15.3 | 166.0 ± 12.9 | 205.7 ± 37.6 | |

|

| ||||

| Il-1β | Non-stressed + Veh | 112.4 ± 21.0 | 101.1 ± 5.2 | 117.8 ± 25.5 |

| Non-stressed + EtOH | 49.8 ± 8.2* | 53.1 ± 6.5* | 71.7 ± 11.0 | |

| Stress + EtOH (0 h) | 82.4 ± 12.6 | 96.4 ± 13.4 # | 77.7 ± 25.3 | |

| Stress + EtOH (2 h) | 72.8 ± 13.5* | 72.4 ± 9.1* | 75.0 ± 16.1 | |

| Stress + EtOH (4 h) | 60.5 ± 11.0* | 60.2 ± 8.0* | 88.0 ± 21.7 | |

| Stress + EtOH (24 h) | 47.0 ± 9.7* | 66.2 ± 9.6* | 64.7 ± 9.3 | |

|

| ||||

| Tnf-α | Non-stressed + Veh | 102.8 ± 9.2 | 101.7 ± 6.6 | 104.5 ± 11.4 |

| Non-stressed + EtOH | 56.4 ± 7.1* | 50.3 ± 6.4* | 68.9 ± 6.2* | |

| Stress + EtOH (0 h) | 56.3 ± 10.7* | 67.1 ± 7.3* | 71.3 ± 5.8* | |

| Stress + EtOH (2 h) | 52.6 ± 5.4* | 74.2 ± 9.6*# | 70.3 ± 12.1* | |

| Stress + EtOH (4 h) | 76.7 ± 5.8*# | 70.0 ± 6.4*# | 72.4 ± 15.9* | |

| Stress + EtOH (24 h) | 35.3 ± 5.0*# | 50.9 ± 6.1* | 45.4 ± 5.1* | |

Rats were either exposed to 2 hours of acute footshock or remained non-manipulated. Half of the non-stressed controls were given a vehicle a challenge (Non-stressed + Veh), whereas the other half of non-stressed rats were administered an ethanol challenge (Non-stressed + EtOH). Stressed rats were exposed to a 2 hour footshock procedure. Following shock, all stressed animals were intubated with ethanol, but at varying times post-stress: immediately after [Stress + EtOH (0 h)], 2 hours after [Stress + EtOH (2 h)], 4 hours after [Stress + EtOH (4 h)], or 24 hours after [Stress + EtOH (24 h)]. Three hours after challenge with the intragastric intubation, brains were collected and prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) examined for possible stress- and/or ethanol-associated changes in relative gene expression. Gene targets examined included interleukin (Il)-6, nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (IκBα), interleukin (Il)-1β, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnf-α). The relative change in gene expression for each experimental group is shown, plus or minus the standard error of the mean (SEM).

A significant difference from the non-stressed, vehicle control group is identified by an asterisk (*), whereas a significant difference relative to the non-stressed, ethanol-exposed group is denoted by a pound sign (#).

Before conducting analyses of cytokine data, Gapdh expression was first examined as a separate target in order to assess any possible differences across groups in expression of this reference gene. In Experiment 1, no significant differences were present for Gapdh expression. Furthermore, Gapdh expression was not statistically different across groups in the analysis of hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, or amygdala in Experiment 2. While there was a small but reliable main effect of Drug exposure for Gapdh expression in the PVN (ethanol-exposed lower than vehicle-exposed, overall), the magnitude of this difference was quite small (i.e., 23.7% decrease for ethanol-exposed relative to vehicle-exposed groups) and did not significantly alter the pattern of cytokine changes or interpretation of data. Hence, in all analyses, gene expression of cytokine targets was quantified relative to expression of Gapdh using the 2−ΔΔC(T) method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001), with non-stressed vehicle controls serving as the ultimate control group. Specifically the equation used was: 2^-[(C(t) target gene − C(t) Gapdh for individual) − (mean of ultimate control group: C(t) target gene − C(t) Gapdh)] × 100. Thus, in all figures and tables showing inflammatory genes, this equation was used to calculate relative gene expression.

2.1.7 Blood ethanol concentrations

BECs11 were determined in 5-µl aliquots using an Analox AM-1 alcohol analyzer (Analox Instruments, Lunenburg, MA). The machine was calibrated using a 100 mg% industry standard, with a quality control solution (known ethanol concentration between 74.2 and 86.4 mg/dL) used to confirm accurate calibration of the machine. Additionally, the quality control was analyzed every 12–15 samples to ensure continued accuracy of measurement of BECs. BECs were recorded in milligrams per deciliter (mg%). The floor of assay sensitivity using the Analox is approximately 12–20 mg/dL, as evidenced by background BEC measurements obtained from rats never exposed to ethanol (Buck et al., 2011; Richey et al., 2012). As such, measurements at or below those observed in vehicle-injected rats were interpreted as zero values.

2.1.8 Measurement of corticosterone concentrations

Quantitative determinations of corticosterone concentrations were accomplished using commercially available corticosterone EIA12 kits (Assay Designs; Ann Arbor, MI). Samples were diluted 1:30 and heat inactivated (immersion in 75 °C water for 60 min) to denature endogenous CBG13, which has shown to produce a much more reliable and uniform denaturation of CBG than the enzyme cleavage step provided by the kit (unpublished observations). The ELISA14 has been shown to have a sensitivity of 27.0 pg/ml and inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of 5.65% and 3.15%, respectively. Corticosterone concentrations observed in the present experiments were consistent to those previously reported by our laboratory following stress and ethanol manipulations (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015; Gano et al., 2016).

2.2 Experiment 1

The Goal of Experiment 1 was to determine whether an acute stress challenge (footshock) would affect the pattern of acute ethanol-induced alterations in central cytokine expression observed previously (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015). Prior studies have reported that both footshock and acute ethanol challenge alone produce distinct changes in central cytokine expression that vary as a function of CNS15 structure and cytokines of interest. For instance, whereas footshock exposure has been shown to induce a rapid increase in Il-1β gene expression in the PVN (e.g., Buck et al., 2011), administration of acute ethanol has been reported to significantly increase Il-6 and IκBα gene expression across multiple brain regions (hippocampus, PVN, amygdala) during intoxication (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015). Interestingly, our prior work demonstrated that when footshock exposure was imposed during ethanol withdrawal, footshock-induced increases in Il-1β were largely unaffected by an earlier ethanol challenge (Buck et al., 2011). Thus, in the present study, the order of challenges was reversed (i.e., stress exposure preceded ethanol challenge) such that the potential effects of recent stress history on the cytokine response evoked by acute ethanol challenge could be examined. To do this, we began with an acute stress experiment in which the interval between stress cessation and ethanol challenge was systematically varied, but with the cytokine response to ethanol assessed at a fixed time post-ethanol exposure (during intoxication).

2.2.1 Methods

A total of 50 male rats were used in this 6-group, between subjects experiment (see Figure 1B for a diagram of experimental groups and time line). Two groups of rats remained in the homecage and served as non-stressed controls, with one of these groups eventually receiving a vehicle (n = 10) challenge, and the other an acute ethanol challenge (n = 8). In contrast, the remaining rats were equally divided (n = 8) into one of four possible stress conditions. For these groups, all rats were first exposed to the 2 h footshock procedure detailed above. Following footshock termination, animals were then given an acute ethanol challenge either 0, 2, 4, or 24 h after stress termination, with the 2 and 24 h time points having been previously reported to be a time at which acute stress significantly exacerbates the behavioral (ataxic) effects of acute ethanol (see Drugan et al., 2007). Tissue and trunk blood were collected 3 h after ethanol delivery. Time of day for footshock exposure was varied such that time of day of ethanol intubation (and subsequent tissue collection) could be kept constant across groups

2.3 Experiment 2

In Experiment 1, exposure to an acute stressor prior to challenge with ethanol significantly, and selectively, exacerbated ethanol-induced increases in Il-6 expression in the hippocampus during intoxication when the stress and ethanol challenges were separated by 24 hr. As acute and chronic stress have been shown to differentially alter an organism’s response to a subsequent challenge—including ethanol (e.g., Varlinskaya and Spear, 2012) and immunogens (e.g., Dhabhar and McEwen, 1997)—the purpose of Experiment 2 was to compare potential changes in acute ethanol-induced central cytokine expression in animals with or without a history of chronic escalating stress.

2.3.1 Methods

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (N = 34; n = 8–10 per group) were tested in a 2 (Stress: Non-stressed vs. Chronic Escalating Distress) × 2 (Drug Challenge: Ethanol vs. Vehicle) between-subjects factorial design (see Figure 1C). In this experiment, stressed animals were exposed to the CED procedure detailed above, whereas non-stressed control animals remained in the homecage and were non-manipulated except for measurement of body weight on days 1, 6, 11, and 12. The final stress exposure, acute footshock, occurred on day 11. All rats were administered either an acute ethanol challenge or vehicle intubation 24 h after the final footshock stress, or at an equivalent time point for the non-stressed animals. Similar to our previous studies (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015) and Experiment 1, tissue and trunk blood were collected 3 h after intubation.

2.4 Experiment 3

Since intense stress challenges have been shown to alter the synthesis of blood-borne carrier proteins produced predominantly by liver hepatocytes (e.g., Deak et al., 1997; Fleshner et al., 1995), it is possible that prior exposure to an acute stress and/or chronic stress procedure might alter the pharmacokinetics of an acute ethanol challenge. Thus, the goal of Experiment 3 was to perform a detailed time-course of BECs in animals with varying histories of stress exposure (no stress, acute footshock, or the chronic escalating distress model) to test whether ethanol metabolism might be significantly impacted as a function of the stress procedures utilized in the prior two experiments. Additionally, plasma corticosterone concentrations were examined in the same samples as a general index of HPA axis sensitivity to acute ethanol challenge following these different stress conditions.

2.4.1 Methods

Rats (n = 8 per group; N = 34) were exposed to 1 of 3 possible stress conditions (see Figure 1D). Other than periodic assessments of body weight, the non-stressed controls remained non-manipulated in the homecage. A second group, the acute footshock group, remained non-manipulated in the homecage for the first 10 days of the experiment. Rats in this group were then exposed to an acute (2 h) footshock session on experimental day 11. Finally, rats in the third group were exposed to the full CED model. In all stress conditions, animals were weighed on experimental days 1, 6, 11, and 12 prior to any stress procedure(s). On Day 12, all groups were administered an acute ethanol challenge (4 g/kg, i.g.), 24 h after the footshock stress that occurred on Day 11 (or an equivalent time point for the non-stressed controls). Blood samples were then collected (via tail clip) at 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 h after the ethanol challenge, with a baseline (0 h) sample collected immediately before ethanol intubation. Blood samples were centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min, and then serum collected and stored at −20 °C until the time of assay.

2.5 Experiment 4

The outcome of Experiment 3 suggested that, based on BECs, the pharmacokinetics of ethanol did not differ significantly between acute and chronically stressed rats. The goal of Experiment 4 was to assess whether these same stress challenges might alter behavioral sensitivity to ethanol. Loss of Righting Reflex (LORR) was chosen as a gross index of behavioral sensitivity to ethanol, and we hypothesized that significant alterations in latency to LORR, duration of LORR, or the ambient BECs at the time of awakening could be influenced as a result of recent stress history.

Rats (n = 10–12 per group; N = 32) were exposed to 1 of 3 stress conditions (see Figure 1D). Other than periodic assessments of body weight, the non-stressed controls remained nonmanipulated in the homecage. A second group, the acute footshock group, remained nonmanipulated in the homecage for the first 10 days of the experiment, and was then exposed to an acute (2 h) footshock session on experimental day 11. Finally, rats in the third group were exposed to the full CED model. In all stress conditions, animals were weighed on experimental days 1, 6, 11, and 12 prior to any stress procedure(s).

On Day 12, all groups were administered an acute 4 g/kg intraperitoneal (i.p.) ethanol challenge, 24 h after the footshock stress that occurred on Day 11 (or an equivalent time point for the non-stressed controls). Immediately following injection, the latency to lose the righting reflex was assessed. Rats were defined as having lost the righting reflex when a given animal was no longer capable of righting itself twice within a 60 second period when laid on its back. Once an animal regained the ability to right itself from the supine position twice within 60 seconds, the period of ethanol-induced hypnosis was said to be over (“awakening”) and the duration of LORR recorded. Tail blood samples were collected at the time of awakening for later assessment of BECs according the procedures described above.

2.6 Statistical Analyses

Before analysis, data sets were first examined for possible outliers, with a score diverging by more than 2 standard deviations from the mean of an experimental group being considered an outlier. Identification and treatment of any outliers, lost samples, or missing data is described within the Results section. Data were analyzed according to the design described at the beginning of each Results section for a particular experiment, with the level for significance set at p < 0.05 in all analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Experiment 1

Corticosterone, BEC, and cytokine expression data were analyzed using one-way ANOVAs16, with Fisher’s LSD17 post hoc test used to identify the locus of any significant differences between groups. One animal from the group given acute ethanol immediately after footshock exposure was lost due to an intubation error, and was thus not included in any analyses. In some instances, it was necessary to remove outliers in the analysis of gene expression data, either due to processing error for that particular sample, or because of an extreme value. Because of these reasons, 3 samples were lost from the hippocampus (1 each from the non-stressed control group given vehicle, the non-stressed group given acute ethanol, and the group given ethanol 4 h after footshock), 1 was lost from the prefrontal cortex (from the group given ethanol 2 h after footshock), 1 sample was not included from the amygdala (the non-stressed group given ethanol), and 2 PVN samples were excluded (1 each from the groups given ethanol 2 h and 4 after shock). Furthermore, for the Tnf-α reactions in both the amygdala (1 sample from the group intubated with ethanol immediately after footshock) and PVN (nonstressed and administered ethanol), 1 sample was excluded because of an amplification failure.

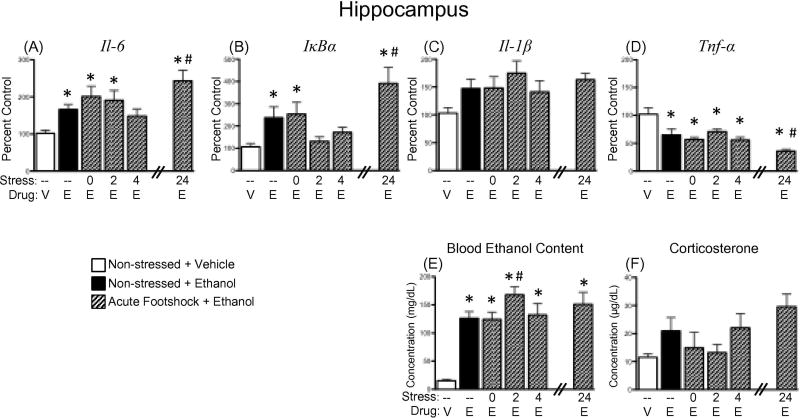

3.1.1 BECs

A significant effect of Experimental Condition revealed that, overall, all groups administered an acute ethanol challenge had elevated blood ethanol concentrations relative to non-stressed vehicle controls [F(5,44) = 12.265, p < .01]. Furthermore, a post hoc analysis of this main effect showed that the group challenged with ethanol 2 h after acute footshock had significantly higher BECs relative to non-stressed ethanol-exposed animals (see Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Effects of ethanol and/or acute stress on expression of neuroimmune factors, as well as blood ethanol content, and corticosterone concentrations. Rats were challenged intragastrically with either vehicle (V) or 4 g/kg ethanol (E), and blood and brains were collected 3 h later for analysis. Two groups of rats were non-manipulated prior to drug challenge, as indicated by the dashed line (–) under the bars for those groups. The other four experimental groups were all exposed to acute footshock (2 h in duration), with ethanol then delivered either 0, 2, 4, or 24 h after the conclusion of the footshock session (as indicated in the “Stress” line under the bars for those groups, respectively). Gene expression values presented here were from hippocampal punches and include (A) interleukin (Il)-6, (B) nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (IκBα), (C) Il-1β, and (D) tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnf-α). Data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2-ΔΔC(t) method, with Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) used as a reference gene and the nonstressed, vehicle-exposed rats serving as the ultimate control group. Plasma (E) blood ethanol and (F) corticosterone concentrations were also measured. In this and all other figures, bars denote group means ± standard error of the mean (represented by vertical error bars). A significant difference from the non-stressed, vehicle control group is identified by an asterisk (*), whereas a significant difference relative to the non-stressed, ethanol-exposed group is denoted by a pound sign (#).

3.1.2 Plasma corticosterone

Although there was a strong trend for all groups exposed to ethanol to have higher plasma corticosterone than the vehicle-exposed controls [F(5,43)=2.215, p = .070]—and more specifically for the group that received ethanol 24 h after acute footshock to have a potentiated plasma corticosterone response—these effects approached but did not achieve statistical significance (see Figure 2F).

3.1.3 Central cytokine expression

3.1.3.1 Interleukin-6

When compared to non-stressed animals given vehicle, acute administration of ethanol significantly elevated expression of Il-6 in the hippocampus at all time points except 4 h after stress, [F(5,40) = 4.80, p < 0.01] and at all time points in the amygdala [F(5,42) = 3.41, p < 0.05] (Figure 2A, Table 1, respectively). Furthermore, when animals were given ethanol 24 h after footshock exposure, expression of Il-6 in the hippocampus significantly exceeded levels seen in non-stressed animals that were given acute ethanol. Ethanol did not significantly impact Il-6 expression in either the prefrontal cortex or PVN (Table 1).

3.1.3.2 IκBα

When IκBα in the hippocampus was compared to non-stressed controls given vehicle, acute ethanol was found to significantly increase expression of this gene in the non-stressed group, as well as in the groups given ethanol immediately after footshock and 24 h after footshock [F(5,40) = 5.09, p < 0.01] (Figure 2B). Additionally, this ethanol-induced increase in IκBα expression was even greater in the animals given ethanol 24 h after footshock relative to those that were not stressed but given the same acute ethanol challenge. In contrast, ethanol did not induce significant alterations in IκBα expression in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, or PVN (Table 1).

3.1.3.3 Interleukin-1 beta

No significant effects of ethanol (or ethanol plus footshock stress) were seen for Il-1β expression in either the hippocampus or PVN (Figure 2C, Table 1, respectively). In contrast, rats acutely challenged with intragastric ethanol exhibited significant reductions in expression of Il-1β within the prefrontal cortex [F(5,42) = 3.63, p < 0.01] and amygdala [F(5,42) = 5.04, p < 0.01; Table 1 for both] in comparison to non-stressed and vehicle-exposed controls. Rats administered ethanol immediately after footshock did not show a reduction in Il-1β in either of these brain structures.

3.1.3.4 Tumor necrosis factor alpha

In all four brain regions, acute administration of ethanol significantly suppressed expression of Tnf-α when all groups given ethanol were compared to non-stressed, vehicle-treated controls [hippocampus: F(5,40) = 8.34, p < 0.0001; prefrontal cortex: F(5,42) = 9.88, p < 0.00001; amygdala: F(5,41) = 7.25, p < 0.0001; PVN: F(5,40) = 3.83, p < 0.01]. In the hippocampus (Figure 2D) and prefrontal cortex (Table 1), ethanol-induced suppression of Tnf-α was even greater in rats given ethanol 24 h after footshock relative to those that were non-stressed but also ethanol-exposed. In contrast, this ethanol-related suppression of Tnf-α expression was blunted in animals administered ethanol 4 h following footshock in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, as well as in animals given ethanol 2 h after footshock in the amygdala (see Table 1).

3.2 Experiment 2

All data in this experiment were analyzed using 2 (Stress) × 2 (Drug Exposure) between subjects factorial ANOVAs, with Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests used to examine the locus of significant differences in the case of a statistically significant interaction. In the hippocampus, 2 samples were lost only in the analysis of Tnf-α expression because of a failure of amplification (1 from the non-stressed control group administered vehicle; 1 from the group exposed to CED and given acute ethanol). For the PVN, 1 sample was excluded from all analyses due to abnormally low (< 2 standard deviations from the mean) Gapdh expression (from the CED group given ethanol).

3.2.1 Body weight gain

Analysis of body weight gain (in grams) demonstrated a significant increase in weight across days for all groups up to Day 11, but with stressed animals gaining significantly less weight than the non-stressed controls [Stress × Day interaction: F(3,90) = 86.30, p < 0.05]. While weight continued to increase for the non-stressed animals from Day 11 to Day 12, animals exposed to escalating distress exhibited significant weight loss following the acute footshock procedure on Day 11 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Body weights (g) of rats in Experiments 2 and 3.

| Day 1 | Day 6 | Day 11 | Day 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 2 | Non-stressed + VEH | 322.6 ± 4.5 | 342.3 ± 5.7 | 356.2 ± 5.5 | 359.7 ± 6.0 |

| Non-stressed + EtOH | 324.1 ± 2.4 | 344.9 ± 3.1 | 361.6 ± 4.3 | 363.6 ± 3.9 | |

| Chronic stress + VEH | 327.9 ± 1.9 | 331.0 ± 4.3 | 338.6 ± 4.6 | 326.1 ± 4.0 | |

| Chronic stress + EtOH | 336.4 ± 5.3 | 350.1 ± 5.5 | 353.0 ± 5.0 | 337.4 ± 4.8 | |

|

| |||||

| Experiment 3 | Non-stressed | 319.2 ± 4.0 | 337.2 ± 4.5 | 348.8 ± 5.5 | 351.8 ± 5.7 |

| Acute footshock | 324.9 ± 6.0 | 344.0 ± 7.0 | 360.6 ± 6.9 | 349.1 ± 7.4 | |

| Chronic stress | 329.6 ± 7.8 | 341.0 ± 8.5 | 346.6 ± 10.3 | 335.4 ± 8.9 | |

Rats in Experiments 2 and 3 were non-stressed, acutely stressed, or exposed to a chronic escalating distress procedure. Body weights were assessed on Days 1, 6, 11, and 12 of the chronic stress paradigm, with non- stressed and acutely-stressed animals also weighed on these days. The mean body weight for each experimental group is shown, plus or minus the standard error of the mean (SEM). In Experiment 2, rats were challenged with either vehicle (VEH) or ethanol (EtOH) after the final stress exposure. In the analysis of these body weight data, a Day x Stress interaction demonstrated that, while weight gain generally increased across all days of measurement, the stressed animals gained overall less than the non-stressed control groups (as shown in italics). Furthermore, rats in the chronic stress groups exhibited a significant decrease in body weight from Day 11 to Day 12 following an acute footshock exposure on Day 11 (as indicated by bolded values), whereas controls continued to show an increase from Day 11 to Day 12. In Experiment 3, no body weight differences were observed across groups on any given day of measurement. From Day 11 to Day 12, however, the acute and chronic stress groups exhibited significant reductions in weight following footshock—an effect that was not observed in the non-stressed controls (indicated with bold text).

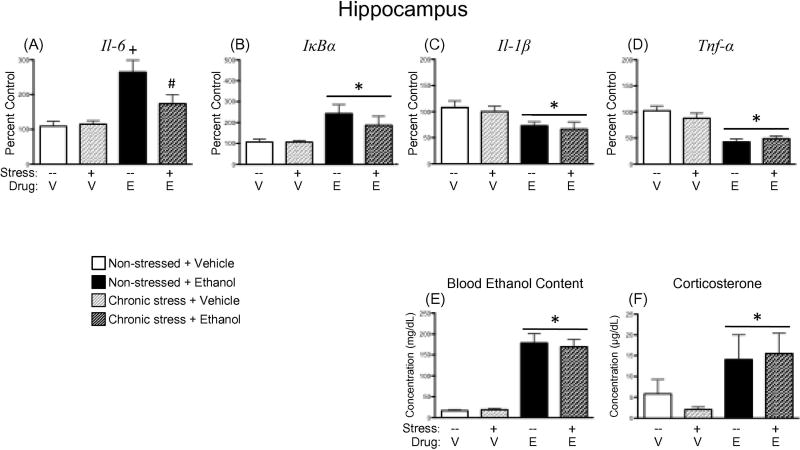

3.2.2 Blood ethanol and corticosterone concentrations

A main effect of Drug Exposure revealed that, overall, acute ethanol administration led to significant increases in blood ethanol content [F(1,30) = 131.11, p < 0.00001; Figure 3E] and corticosterone concentration [F(1,30) = 6.57, p < 0.05; Figure 3F], but that these elevations were not significantly impacted by a chronic stress history prior to ethanol challenge.

Figure 3.

Effects of ethanol and/or chronic stress on expression of neuroimmune factors, as well as blood ethanol content and corticosterone concentrations. Rats were given an acute intragastric challenge of either vehicle (V) or 4 g/kg ethanol (E), with blood and brains collected 3 h later for analysis. Two groups of rats were non-manipulated prior to drug challenge, as indicated by the dashed line (–) under the bars for those groups. The other two experimental groups were exposed to a chronic escalating stress procedure, which is noted by a plus sign (+) under the bars for those groups. Drug challenge was administered 24 h after the final acute footshock session for the stressed rats. Gene expression values presented here were from hippocampal punches and include (A) interleukin (Il)-6, (B) nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (IκBα), (C) Il-1β, and (D) tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnf-α). Data were calculated as a relative change in gene expression using the 2-ΔΔC(t) method, with Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) used as a reference gene and the non-stressed, vehicle-exposed rats serving as the ultimate control group. Plasma (E) blood ethanol and (F) corticosterone concentrations were also measured. A main effect of ethanol administration has been identified by placing a horizontal line with an asterisk (*) above the bars for the ethanol-exposed groups. In the case of an interaction (panel A), the plus sign (+) indicates a significant difference from the non-stressed, vehicle-treated group; whereas a pound sign (#) indicates a significant difference relative to the non-stressed, ethanol-exposed group. No main effects of Stress were observed in any of the analyses for this experiment.

3.2.3 Central cytokine expression

3.2.3.1 Interleukin-6

Acute ethanol administration led to significant increases in Il-6 expression across all brain structures examined. In the hippocampus, ethanol-related elevations in Il-6 were blunted by a history of chronic stress (Figure 3A), as animals in this group did not exhibit a significant increase in Il-6 expression when compared to their vehicle-exposed counterparts [Drug Exposure × Stress interaction: F(1,30) = 4.64, p < 0.05]. Within the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and PVN (Table 3), however, this ethanol-related increase in Il-6 expression occurred regardless of stress history [main effect of Drug Exposure for prefrontal cortex: F(1,30) = 13.39, p < 0.001; amygdala: F(1,30) = 17.52, p < 0.001; and PVN: F(1,29) = 11.40, p < 0.01].

3.2.3.2 IκBα

Similar to what was observed for Il-6 expression, acute ethanol resulted in general elevations in IκBα expression in the hippocampus [F(1,30) = 13.01, p < 0.01; Figure 3B], prefrontal cortex [F(1,30) = 13.65, p < 0.001], amygdala [F(1,30) = 14.48, p < 0.001], and PVN [F(1,29) = 25.56, p < 0.0001] (Table 3). While there was a trend for chronic stress to attenuate ethanol-associated increases in expression of this gene target in the PVN, the Drug Exposure×Stress interaction did not reach significance in this instance [F(1,29) = 2.88, p = 0.10].

3.2.3.3 Interleukin-1 beta

Significant reductions in Il-1β expression were observed when animals were challenged with acute ethanol [main effect of Drug Exposure in the hippocampus: F(1,30) = 9.02, p < 0.01, Figure 3C; prefrontal cortex: F(1,30) = 7.41, p < 0.05, Table 3; amygdala: F(1,30) = 12.88, p < 0.01, Table 3; and PVN: F(1,29) = 5.50, p < 0.05, Table 3]. In no instance was an ethanol-induced reduction in Il-1β expression modified by a prior stress history.

3.2.3.4 Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Administration of acute ethanol resulted in significant reductions in Tnf-α expression across all four structures of interest [main effect of Drug Exposure for hippocampus: F(1,28) = 35.75, p < 0.00001, Figure 3D; prefrontal cortex: F(1,30) = 28.24, p < 0.0001, Table 3; amygdala: F(1,30) = 14.90, p < 0.001, Table 3; and PVN: F(1,29) = 5.76, p < 0.05, Table 3]. Again, as was observed for Il-1β expression, previous exposure to chronic escalating stress did not modify these effects of ethanol in any brain structure examined.

3.3 Experiment 3

When blood ethanol and corticosterone concentrations were examined across time in Experiment 3, data were analyzed using 3 (Stress: Non-stressed vs. acute footshock vs. CED exposure) × 6 (Time Point: 0, 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 h) mixed ANOVAs. One animal from the CED group was lost due to an intubation error. In this same group, we were unable to collect samples from two rats at the 1.5 h time point because of an unanticipated fire alarm. In order to analyze these repeated-measures data, the mean of the 0.5 h and 3 h time point for each animal was substituted as an estimate of their missing 1.5 h time-point sample. Importantly, all fire alarm-related noises were not audible in the colony room (where tail blood was taken) during experimentation, and thus this event did not impact the animals during the experiment.

3.3.1 Body weight gain

Analysis of body weight across days 1, 6, 11 and 12 of the experiment revealed a significant main effect of Day [F(3,66) = 156.90, p < 0.00001], as well as a significant interaction of Day with Stress Condition [F(6,66) = 15.53, p < 0.00001]. Post hoc analysis of this interaction showed that body weight generally increased across the first 11 days of the experiment for all stress groups (see Table 2). While this increase in weight continued to Day 12 in the non-stressed animals, groups that were exposed to footshock on Day 11 exhibited a significant decline in body weight from Day 11 to Day 12. In spite of this interaction, no significant differences between any of the stress conditions were observed on any given day of measurement.

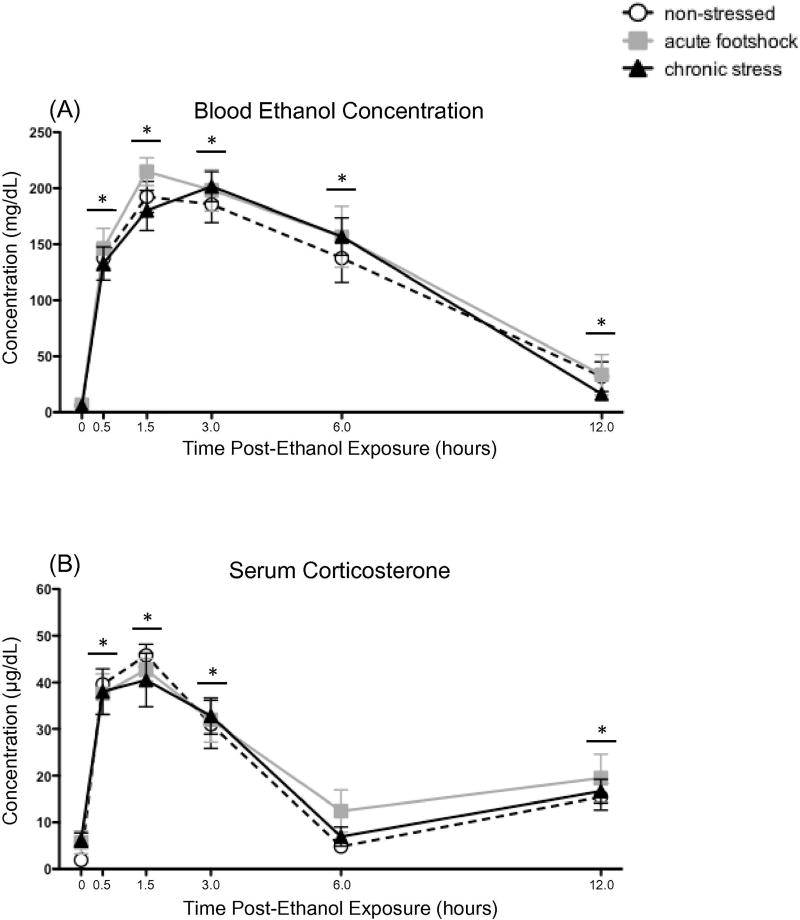

3.3.2 BECs

A significant main effect of Time [F(5,110) = 187.99, p < 0.00001] showed that BECs were significantly elevated relative to baseline at all time points (Figure 4A). Although BECs were approaching baseline levels by the 12 h time point, they were still statistically elevated relative to the pre-ethanol measurement. No significant main effects or interactions involving Stress Condition were observed in this analysis. The CED group exhibited a trend for BECs to peak at the 3 h time point, whereas all other groups appeared to peak at the 1.5 h measurement. However, this apparent difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Time-course of blood ethanol concentrations and corticosterone concentrations following ethanol in challenge in rats exposed to acute or chronic stress. Tail blood was collected before (baseline; 0 h), as well as 0.5, 1.5, 3.0, 6.0, and 12.0 h following a 4 g/kg intragastric ethanol challenge and subsequent (A) blood ethanol and (B) serum corticosterone concentrations were assessed. Non-stressed controls remained non-manipulated in the homecage during the stress phase of the experiment, and until the time of ethanol challenge (white circles). Rats in the acute footshock group (gray squares) were non-manipulated in the homecage for the first 10 days of the experiment, and were then exposed to acute (2 h) footshock on Day 11, with ethanol delivered 24 h later. Animals in the chronic escalating distress group (black triangles) were exposed to the full 11-day chronic escalating distress procedure, and ethanol was administered 24 h after the final footshock stressor. Symbols denote group means ± standard error of the mean (represented by vertical error bars). A horizontal line with an asterisk (*) above the symbols for that time point indicates a significant difference from the baseline measurement, when collapsed across Stress condition. No main effects or interactions involving Stress were observed in these analyses.

3.3.3 Serum corticosterone

Relative to baseline levels, acute ethanol resulted in significant elevations in serum corticosterone concentrations (Figure 4B) at the 0.5, 1.5, and 3.0 h time points [main effect of Time: F(5,110) = 74.22, p < 0.00001]. By the 6.0 h time point, however, serum corticosterone was no longer statistically different from pre-ethanol levels. At the 12 h time point, corticosterone concentrations increased slightly—but significantly— compared to baseline, likely due to circadian influences on circulating corticosterone. No significant main effects or interactions involving Stress Condition were apparent in this analysis.

3.4 Experiment 4

3.4.1. Latency to LORR

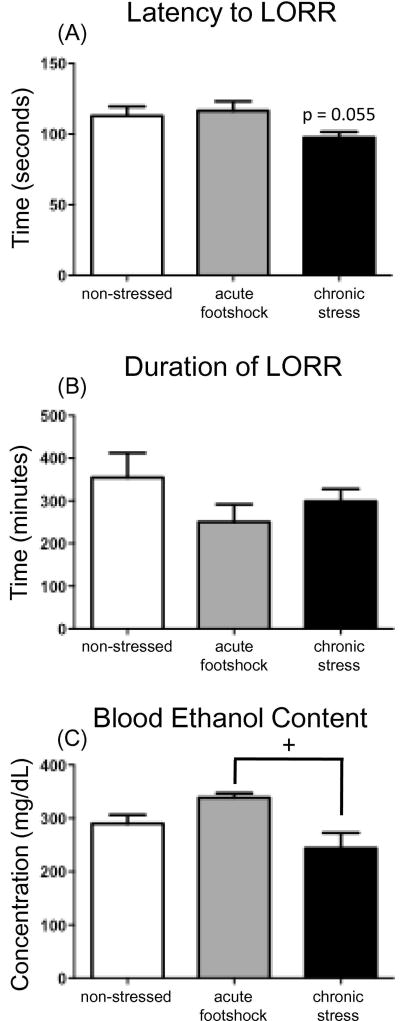

The one-way ANOVA analyzing latency to reach a loss of the right reflex indicated a non-significant trend for chronic stress to reduce the time required to reach LORR [F(2, 27) = 3.23, p = 0.055; see Figure 5A].

Figure 5.

Loss of righting reflex (LORR) test day data for Experiment 4, including (A) the latency to lose LORR, (B) duration of LORR, and (C) blood ethanol content measured in tailblood samples collected at awakening. Non-stressed controls remained non-manipulated in the homecage during the stress phase of the experiment, and until the time of ethanol challenge (white bars). Rats in the acute footshock group (gray bars) were non-manipulated in the homecage for the first 10 days of the experiment, and were then exposed to acute (2 h) footshock on Day 11, with ethanol delivered 24 h later. Animals in the chronic stress group (black bars) were exposed to the full 11-day chronic escalating distress procedure, and ethanol was administered 24 h after the final footshock stressor. The plus sign (+) denotes a significant difference between the stress groups (acute vs. chronic). No groups were found to be significantly differen8t from the non-stressed controls in any of the measures analyzed and no main effects of Stress were observed in the analysis of the behavioral LORR data.

3.4.2. Duration of LORR

No significant effects of acute or chronic stress were observed on the duration of the LORR (see Figure 5B).

3.4.3. BECs at awakening

Although sleep time did not differ between groups, analysis revealed BECs at awakening to be impacted by stress history [main effect of Stress F(2, 27) = 5.09, p < 0.05]. While no significant differences were observed in the stress groups relative to the non-stress controls, the acute stress group showed significantly higher BECs at awakening than did the chronic escalating distress groups (post hoc p < 0.01) (see Figure 5C).

4. Discussion

The current series of experiments explored the effects of acute versus chronic stress exposure on subsequent ethanol-induced alterations in brain cytokines, as well as the effects of these stressors on acute ethanol pharmacokinetics. The overarching goals of these projects were to: (i) determine whether stress history might modify neuroimmune consequences of acute ethanol exposure; (ii) assess to what extent the recent stress history might differentially impact central cytokine expression in ethanol-sensitive brain regions; and (iii) examine whether recent stress history might impact other indices of ethanol sensitivity (ethanol pharmacokinetics, HPA responses, and behavioral sensitivity using LORR). The results of these experiments again demonstrated that acute ethanol intoxication significantly increases mRNA expression of both Il-6 and IκBα, while conversely suppressing expression of Il-1 and Tnf-α, across several brain regions. We have now repeatedly demonstrated that an acute binge-like ethanol challenge results in this pattern of RANGE (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2014; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., 2015) in hippocampus, amygdala, and PVN, and does so with different routes of exposure. In the present report, we now also show that the prefrontal cortex is another brain region responsive to this ethanol-induced RANGE. The consistent observation across multiple studies of increased IκBα expression during acute ethanol intoxication suggests activation of the NF-κB18 signaling cascade, as IκBα is considered a reporter of NF-κB activation (Hacker and Karin, 2006). It is unclear at this time whether ethanol-induced activation of Il-6 pathways are functionally related to, or independent of, increased NF-κB, though it is likely that such interactions could occur via PI3K19 or other mechanisms (Heinrich et al., 2003).

Additionally, the current report demonstrated that acute stress exacerbated ethanol-related elevations in these immune factors in the hippocampus, whereas chronic stress attenuated ethanol-induced Il-6 expression in this same structure. While, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate a differential impact of acute versus chronic stress exposure on later ethanol-induced expression of brain cytokines, these results seem consistent with some previous research investigating the effects of stress on other measures of ethanol responsivity. More specifically, and similar to these data, there have been some reports that acute stressors enhance sensitivity to a later ethanol challenge. In studies by Drugan and colleagues, acute footshock (but not restraint or forced cold swim) resulted in an exacerbated ataxic response to a subsequent low-to-moderate acute ethanol challenge (Drugan et al., 1996; Drugan et al., 2007). Additionally, a mild acute stress exposure—handling—exacerbated the tachycardic and hypothermic response to acute ethanol (Peris and Cunningham, 1986). In contrast, other groups have demonstrated that repeated/chronic exposure to various stressors attenuated some behavioral responses to ethanol. For example, when indexing ethanol responsiveness in terms of ethanol-induced hypnosis, a long-term history of social isolation decreased duration of the loss of the righting reflex in selectively bred mice (Jones et al., 1990; Matsumoto et al., 1997; Parker et al., 2008). Moreover, 5 days of restraint stress was reported to decrease ethanol-induced hypnosis following 4 g/kg in adult, but not adolescent, rats (Fernandez et al., 2016). As previously discussed, however, the overall literature examining the effects of stress on ethanol intake and responsiveness is mixed, with other studies finding no effects of stress, or even results opposite to these (e.g., Blakley and Pohorecky, 2006; Boyce-Rustay et al., 2007; Boyce-Rustay et al., 2008; Sze, 1993). It is likely that a plethora of variables influence the outcomes of experiments of this nature, including species; strain; type, duration, and/or intensity of stressor used; time of assessment of ethanol responsivity (i.e., intoxication vs. withdrawal); and ethanol-induced response assessed. Indeed, even when considering the effects of footshock on ethanol-induced ataxia, it was observed that controllability of the stressor determines the effect of stress on ethanol responsivity, with controllable stress actually resulting in decreased sensitivity to ethanol, whereas uncontrollable stress enhanced sensitivity (e.g., Drugan et al., 1996).

An important contribution of the present work is systematic examination of the time interval between stress and ethanol exposure, which may be an especially important variable to consider. For example, in Experiment 1, acute stress only augmented expression of ethanol-induced cytokine expression when there was a considerable delay (24 hr) between stress exposure and ethanol challenge. Instead, ethanol delivery immediately or soon after stress cessation tended to suppress ethanol-induced expression of Il-6 (4 hr) and IκBα (2 or 4 hr later). Although the mechanism underlying the discrepancy between ethanol-induced changes in the first few hr after stress cessation and those observed with a 24 hr delay are not clear at this time, several possibilities exist. For instance, stress-related alterations in inflammatory pathways are still significant when ethanol is delivered in close temporal proximity to the stressor (Hueston and Deak, 2014), and thus any observed changes could represent a combination of acute stress mechanisms and ethanol effects. In addition, plasma CORT is substantially elevated immediately after footshock, which may also contribute to the timing-specific outcomes of acute stress on neuroimmune gene expression, as CORT can have duplicitous effects on neuroimmune processes depending on dose and timing of CORT (Frank et al., 2017; Frank et al., 2013). Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that time-of-day could alter stress-alcohol interactions, since neuroimmune sensitivity is known to vary across the circadian cycle (Fonken et al., 2016). Thus, a variety of mechanisms could account for the time-dependent effects of stress on alcohol responses, an issue for ongoing studies in our lab. Nevertheless, the present studies are the first to demonstrate a differential influence of acute and chronic stress history on neuroimmune responses provoked by ethanol intoxication.

At this time, it is unclear what neural and/or behavioral processes might be influenced by stress-induced plasticity of the Il-6 response in the hippocampus to ethanol. Given that the hippocampus has been shown to be a very stress-(McEwen et al., 2015; McEwen et al., 2016; Smith and Vale, 2006) and ethanol-sensitive (Chin et al., 2010; Matthews and Morrow, 2000; Nixon, 2006) brain region, it is not surprising that the combination of these two stimuli uniquely influenced cytokine expression in this structure. As recently reviewed by Gruol (2015), numerous studies now suggest that IL-6 is a molecule with a critical role in synaptic transmission and plasticity, as well as cognitive function. For example,Donegan et al. (2014) demonstrated that inhibition of IL-6 (or it’s downstream signaling pathway) in the orbitofrontal cortex significantly impaired reversal learning behavior in an attentional set-shifting task. In the same study, it was also reported that chronic stress-induced deficits in reversal learning were ameliorated by over-expression of IL-6 in this brain structure. Similar to the effects of chronic stress, acute antigen exposure (e.g., LPS20) has been shown to result in deficits in several memory tasks (Kranjac et al., 2012; Shaw et al., 2001), with genetic deletion of IL-6 in mice attenuating these LPS-induced memory impairments, as well as LPS-induced increases in cytokine expression in the hippocampus (Sparkman et al., 2006). Burton and Johnson (2012) observed that inhibition of IL-6 through the trans-signaling pathway (via i.c.v.21 administration of sgp13022) similarly abrogated LPS-related deficits in context fear conditioning in aged mice. Furthermore, Gruol and colleagues reported that transgenic mice with an over-expression of IL-6 in astrocytes exhibited altered synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices in response to acute ethanol (Hernandez et al., 2016). Taken together, studies such as these suggest that it is possible that the interaction of stress and ethanol on hippocampal Il-6 expression observed in the current study might be associated with neural and behavioral alterations in hippocampal-based learning and memory processes, and in particular, those that are sensitive to disruptions by stress and/or ethanol exposure. This is an intriguing possibility and will be an important consideration and focus for future research.

While the current experiments are, to our knowledge, the first to demonstrate an impact of stress history on ethanol-induced alterations in immune factors, the mechanisms by which this interaction might take place are still unknown. As ethanol can readily cross the blood brain barrier, it is a chemical that can directly impact a multitude of cells in the CNS, including neurons, microglia and even astrocytes (for review see Deak et al., 2012). Communication between these types of cells has been shown to be involved in neuroadaptive mechanisms in the brain, thus potentially contributing to the ethanol-induced increases in cytokines (Deak et al., 2012). It is possible, then, that a history of chronic stress might disrupt neuronal-glial communication, hence decreasing gene expression of Il-6. Alternatively, since stress and glucocorticoids have also been shown to impact cytokine regulation, it is possible that stress-related changes in the HPA axis response to acute ethanol might have contributed to these results. Indeed, Frank and colleagues (e.g., Frank et al., 2014; Frank et al., 2012) recently argued that the stress-induced rise in corticosterone may be one mechanism by which acute stress primes microglial expression of cytokines. In Experiment 3, however, chronic stress history did not impact the corticosterone response to an acute ethanol challenge. Thus, stress effects on Il-6 expression are not likely due to stress-associated alterations in ethanol-induced stimulation of glucocorticoids, though this should be tested in future studies. Importantly, Experiment 3 also demonstrated no significant stress-associated alterations in blood ethanol content following an acute ethanol challenge, supporting the conclusion that stress history did not simply alter the pharmacokinetics to an ethanol administration. Despite comparable pharmacokinetics, however, Experiment 4 indicated that recent stress history significantly influenced sensitivity to the hypnotic effects of ethanol. For instance, rats that were acutely stressed showed the highest BECs once they regained the righting reflex despite exhibiting a duration of LORR that was similar to the other groups. On the other hand, rats that were chronically stressed had the lowest BECs upon awakening, while also achieving LORR more quickly than the other groups. Together, these data seem to suggest that chronic stress is increasing sensitivity to the hypnotic effects of acute ethanol, whereas acute stress appears to be reducing sensitivity. Indeed, it is possible that acute stress could be inducing some degree of acute tolerance to the sedative effects of an acute ethanol challenge. Although the present studies did not address the specific mechanisms underlying changes in behavioral sensitivity to ethanol produced by acute versus chronic stress, they provide a strong foundation for future mechanistic studies, which are now ongoing in our lab.

5. Conclusions

In sum, results from these experiments demonstrate the powerful influence that recent stress history can exert over an individual’s response to acute alcohol intoxication. While other studies have routinely tested the impact of stress history on alcohol consumption with wildly varying results (Becker, 2012; Pohorecky, 1990; 1991; Spanagel et al., 2014), we took the alternative perspective in our work that a certain number of individuals will experience binge-like ethanol exposures with varying intervals after termination of the stressful event. This may be particularly true in the case of, or have specific relevance for, interactions between traumatic events and the eventual development and progression of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) with comorbid alcohol use disorder (Gilpin and Weiner, 2017). The demonstration that ethanol intoxication 24 h after (but not within a few hours of) stress cessation exacerbates intoxication-related changes in Il-6 and IkBa expression suggests a lingering effect of recent stress history that may persist beyond the acute stress recovery period. This, combined with a categorically opposite response to alcohol when the stress challenge was chronic in nature, may help define more specific parameters (e.g., recovery interval, type of stress experiences) on which future voluntary intake studies can be designed. In addition, the present findings further support the notion that recent stress history may be a critical feature that determines the neuroimmune consequences of, and pharmacological sensitivity to, subsequent drug challenges (Deak et al., 2015). Thus, as greater working knowledge of the functional implications of acute ethanol intoxication-related changes in cytokines is developed, these studies may more broadly inform novel pharmacotherapeutic targets and strategies for breaking established links between stress, alcohol, and other health conditions that continue to threaten society.

Highlights.

Acute ethanol generally increased Il-6 and IκBα, but decreased Il-1β and Tnf-α

Acute stress potentiated increased hippocampal Il-6 and IκBα expression by ethanol

Chronic stress attenuated elevated hippocampal Il-6 and IκBα expression by ethanol

Pharmacokinetics and corticosterone sensitivity to ethanol were unaffected by stress

Chronic stress increased sensitivity to ethanol-induced hypnosis

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institute of Health under Award Number P50AA017823 to T. Deak and the Center for Development and Behavioral Neuroscience at Binghamton University. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the above stated funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none

Abbreviations: 1hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis; 2interleukin; 3tumor necrosis factor alpha; 4monocyte chemotactic protein; 5nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha; 6paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; 7chronic escalating distress; 8intragastrically; 9ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; 10glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; 11blood ethanol concentrations; 12enzyme immunoassay; 13corticosteroid binding globulin; 14enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; 15central nervous system; 16analysis of variance; 17least significant difference; 18nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; 19Phosphoinositide 3-kinase 20lipopolysaccharide; 21intracerebroventricular; 22soluble glycoprotein 130

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:449–58. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, Higgins P, Pav D, Aloisi R. A dual pathway model of daily stressor effects on rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:161–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02883333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal RG, Hewetson A, George CM, Syapin PJ, Bergeson SE. Minocycline reduces ethanol drinking. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Loeches S, Pascual-Lucas M, Blanco AM, Sanchez-Vera I, Guerri C. Pivotal role of TLR4 receptors in alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and brain damage. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8285–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0976-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC. Effects of alcohol dependence and withdrawal on stress responsiveness and alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. 2012;34:448–58. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v34.4.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater TL. Effects of stress on alcohol drinking: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:131–56. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine SK, Sinha R. Alcohol, stress, and glucocorticoids: From risk to dependence and relapse in alcohol use disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2017;122:136–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakley G, Pohorecky LA. Psychosocial stress alters ethanol's effect on open field behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandino P, Jr, Barnum CJ, Solomon LG, Larish Y, Lankow BS, Deak T. Gene expression changes in the hypothalamus provide evidence for regionally-selective changes in IL-1 and microglial markers after acute stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:958–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Benavidez JM, Geil C, Perra S, Morikawa H, Harris RA. Activation of inflammatory signaling by lipopolysaccharide produces a prolonged increase of voluntary alcohol intake in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S92–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Ponomarev I, Geil C, Bergeson S, Koob GF, Harris RA. Neuroimmune regulation of alcohol consumption: behavioral validation of genes obtained from genomic studies. Addict Biol. 2012;17:108–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Cameron HA, Holmes A. Chronic swim stress alters sensitivity to acute behavioral effects of ethanol in mice. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Janos AL, Holmes A. Effects of chronic swim stress on EtOH-related behaviors in C57BL/6J, DBA/2J and BALB/cByJ mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186:133–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sonne SC. The role of stress in alcohol use, alcoholism treatment, and relapse. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:263–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Knapp DJ, Overstreet DH. Stress sensitization of ethanol withdrawal-induced reduction in social interaction: inhibition by CRF-1 and benzodiazepine receptor antagonists and a 5-HT1A-receptor agonist. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:470–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HM, Hueston CM, Bishop C, Deak T. Enhancement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis but not cytokine responses to stress challenges imposed during withdrawal from acute alcohol exposure in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:203–15. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]