Abstract

This paper describes the development and preliminary trial run of ImpACT (Improving AIDS Care after Trauma), a brief coping intervention to address traumatic stress and HIV care engagement among South African women with sexual trauma histories. We engaged in an iterative process to culturally adapt a cognitive-behavioral intervention for delivery within a South African primary care clinic. This process involved three phases: (a) preliminary intervention development, drawing on content from a prior evidence-based intervention; (b) contextual adaptation of the curriculum through formative data collection using a multi-method qualitative approach; and (c) pre-testing of trauma screening procedures and a subsequent trial run of the intervention. Feedback from key informant interviews and patient in-depth interviews guided the refinement of session content and adaptation of key intervention elements, including culturally relevant visuals, metaphors, and interactive exercises. The trial run curriculum consisted of four individual sessions and two group sessions. Strong session attendance during the trial run supported the feasibility of ImpACT. Participants responded positively to the logistics of the intervention delivery and the majority of session content. Trial run feedback helped to further refine intervention content and delivery towards a pilot randomized clinical trial to assess the feasibility and potential efficacy of this intervention.

Keywords: South Africa, sexual trauma, coping, intervention development, ART adherence

Introduction

Successful adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is critical for reducing health morbidities and disease transmission risk among those who are HIV-infected. This goal is particularly significant in South Africa, which bears the largest HIV burden of any country (UNAIDS, 2016), especially among women, who are disproportionately impacted by HIV (Takuva, Brown, Pillay, Delpech, & Puren, 2017). Despite a robust national program to deliver HIV testing and treatment services, estimates suggest substantial dropout across the HIV care continuum. Among women with HIV who are linked to care, less than two-thirds stayed on ART for at least six months, and only 74% of those achieved viral suppression (Takuva et al., 2017), reflecting substantial gaps in ART adherence in this population.

ART adherence, and HIV care engagement more broadly, may be especially challenging for South African women exposed to the dual epidemics of HIV infection and sexual trauma, both of which occur at high rates in this setting (Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002). Studies estimate that 25 to 50% of South African women have experienced lifetime physical or sexual assault from a male partner (Dunkle et al., 2004; Gass, Stein, Williams, & Seedat, 2011; Jewkes, Penn-Kekana, Levin, Ratsaka, & Schrieber, 2001), and one in ten women have experienced sexual assault from non-partners (Dunkle et al., 2004). More than one-third of South African women are estimated to have a history of childhood sexual abuse (M. Seedat, Van Niekerk, Jewkes, Suffla, & Ratele, 2009). Repeated traumatization across lifetime is common, and in particular women with HIV may be at risk for recurrence of abuse related to negative reactions by sexual partners upon disclosure of HIV status (Dunkle et al., 2004).

Lifetime sexual trauma and its psychological sequelae may compound the stress of managing HIV and interfere with care engagement, leading to poor health and behavioral outcomes. Traumatic experiences such as intimate partner violence are generally associated with poorer adherence to treatment, worsened viral suppression, and health risk behaviors (Hatcher, Smout, Turan, Christofides, & Stockl, 2015; LeGrand et al., 2015). This may be due to heightened risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health disorders such as depression and substance abuse (Breslau, Davis, Peterson, & Schultz, 1997), which could interfere with treatment adherence (Springer, Dushaj, & Azar, 2012). Up to half of South African women attending HIV clinics are estimated to have clinically significant symptoms of traumatic stress (S. Seedat, 2012). More directly, traumatic stress and fear of further trauma exposure may interfere with women’s ability to access care, adhere to ART, and/or disclose their HIV status. South African women with HIV and histories of sexual trauma have reported heightened shame and stigma (Velloza et al., 2015), factors described in this setting as reasons for delaying HIV care enrollment after diagnosis (Watt et al., 2017). Watt and colleagues (2017) found that, even after entering HIV care, few South African women disclosed their sexual trauma to HIV care providers, and several reported that taking their ART re-activated traumatic memories and related distress. Most of these women linked their HIV infection directly or indirectly to a sexually traumatic experience, and described receiving the HIV diagnosis and/or taking ART as stimuli that triggered memories of the trauma and associated symptomatology. Thus, addressing the impact of trauma in the context of managing HIV seems vital to increasing retention in HIV care and adherence to medication, improving the health of women living with HIV in this high-burden setting.

To date, trauma-focused interventions among people living with HIV (PLWH) remain largely restricted to the United States (McLean & Fitzgerald, 2016). In low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), identification and treatment of trauma among PLWH is often constrained by shortfalls in funding, training, and qualified providers of mental health services (Jacob et al., 2007). Integration of mental health care into primary health care settings, as well as task-shifting and training of non-specialist workers to deliver evidence-based psychotherapies and other interventions, are cost-effective strategies to mitigate some of these resource-based challenges (Jack et al., 2014; van Ginneken et al., 2013)—however, such efforts are nascent. There is a need to develop scalable, integrated interventions to address traumatic stress and its potential impact on health behaviors, especially in countries lacking strong mental health infrastructure. In South Africa, the cultural and socioeconomic context is complex, with intersecting histories of social apartheid, wealth disparities, and a large burden of HIV. These contextual factors present unique challenges and necessitate culturally adaptive models of trauma-informed HIV care that occur within the current service delivery setting where at-risk individuals are most accessible.

One evidence-based intervention for addressing the combined impact of HIV and trauma is the CDC- and SAMHSA-endorsed Living in the Face of Trauma (LIFT) intervention in the United States. LIFT was previously shown to significantly reduce traumatic stress (Sikkema et al., 2013), sexual risk behavior (Sikkema et al., 2008), and substance use (Meade et al., 2010) in HIV-infected individuals with childhood sexual abuse histories. Notably, reductions in traumatic stress were fully explained by decreases in avoidant coping, pointing to coping as an important intervention target. Unaddressed, avoidant coping manifests in poor health-related behaviors, including missed medical appointments, high-risk sexual practices, and non-adherence to treatment (Gore-Felton & Koopman, 2008; Weaver et al., 2005). Thus, LIFT provides a strong basis for developing a focused intervention to decrease avoidant coping and reduce traumatic stress among HIV-infected South African women with sexual trauma histories, which may in turn improve their retention in HIV care and ART adherence.

We sought to develop a brief and scalable mental health intervention for South African women who have experienced sexual trauma (ImpACT; Improving AIDS Care after Trauma). The primary goals of this intervention were to decrease avoidant coping, reduce traumatic stress, and improve HIV care engagement from the outset of ART initiation, and be feasibly delivered within the local clinical and cultural context. In this paper, we describe the intervention development process, the iterative formative research that informed the intervention model, and the resulting intervention framework.

Methods

Study site

Clinic-based intervention development took place October 2014 - December 2015 in a primary care clinic in a peri-urban township of Cape Town, South Africa. This clinic provides HIV clinical services including diagnosis and ART. Over 2,500 patients receive HIV care at this clinic each year. Following standard protocols based on government guidelines, patients were eligible to initiate ART when they met any of the following criteria: CD4 <= 500 cells/mm3, presence of an AIDS-defining illness, pregnant or breastfeeding, and/or tuberculosis diagnosis.

Study overview

Development and preliminary trial run of the ImpACT intervention consisted of three sequential phases: (a) preliminary intervention development, drawing on content from a prior evidence-based intervention and psychological literature; (b) contextual adaptation of the curriculum through formative data collection using a multi-method qualitative approach; and (c) pre- testing of trauma screening procedures and an intervention trial run. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at Duke University and the University of Cape Town.

Phase 1: Conceptual foundation for preliminary intervention development

For initial intervention development, we primarily built on theoretical and empirical evidence from prior implementation and evaluation of the U.S.-based LIFT intervention (Meade et al., 2010; Sikkema et al., 2013; Sikkema et al., 2008). LIFT was informed by stress and coping theories (Folkman et al., 1991; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and included components of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) for reducing symptoms of traumatic stress and improving coping related to sexual trauma and HIV. We focused on adapting the following treatment themes: synergistic stress of sexual trauma and HIV; impact of trauma on health behaviors, including ART adherence; safety, intimacy, power, and self-esteem (SIPS); stressor identification and appraisal; adaptive versus maladaptive coping; social support; and reduction of shame and stigma. We undertook an iterative process to develop a preliminary intervention curriculum for subsequent refinement through formative research.

Phase 2: Intervention development and refinement through formative data collection

We used a multi-method qualitative approach to refine the content and delivery of the intervention and inform the study protocol for the subsequent pilot test. General methods and primary areas of inquiry in this qualitative process are presented in Table 1 [Table 1 near here].

Table 1.

Summary of formative research process

| Activity | Key Areas of Inquiry |

|---|---|

| Interviews with clinic and NGO providers | Patient experiences dealing with sexual trauma in the health care setting Referral and treatment systems for sexual trauma in the context of HIV care Current challenges in provision of care and patient engagement Resources currently available for women with sexual trauma Experiences of women with sexual trauma: types, co-occurrence, impact, links with HIV Community perceptions of sexual trauma: Response, stigma, disclosure |

| Interviews and focus groups with patients | Types and timing of trauma experienced Recognition of bidirectional influence of HIV-related stressors and trauma Past experience of talking about trauma and HIV, emotional support Strategies for coping, including unhealthy or avoidant coping Challenges and barriers to care: structural, social, and motivational |

| Pilot screening | Patient response to screening tool for sexual trauma |

| Intervention trial run | Response to intervention component among women with history of trauma Feasibility, flow, and perceived impact of intervention content and delivery schedule |

Interviews with health care and community providers

We conducted eleven key informant interviews (KIIs) with health care providers (i.e., physician, psychologist, social worker, nurses, and adherence counsellors) in the study clinic as well as with staff at nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that provide community-based services for trauma survivors. Semi-structured interview guides were tailored according to the type of services provided. KIIs were conducted by the study coordinator and research assistant and transcribed from recordings. Findings were used to assess perceived feasibility, acceptability, and logistics of the proposed intervention, and to refine the curriculum content.

In-depth interviews and focus group discussions with patients

We conducted fifteen in-depth interviews (IDIs) with HIV-infected women who reported a history of sexual trauma to identify culturally and contextually relevant issues related to sexual trauma and HIV care engagement to be incorporated into the intervention (AUTHOR et al., 2017). Female patients across the HIV care continuum were recruited from the primary care clinic through an initial announcement of a research study opportunity for women. Women who expressed interest were accompanied to a private room where the research assistant specified the trauma-related focus of the study, screened for history of sexual abuse using a brief survey, and consented eligible patients to complete semi-structured IDIs. Interviews included discussion of the HIV diagnosis experience, perceived connections between HIV-related stress and trauma, strategies for coping with sexual trauma, and social influences on HIV care engagement, including the challenges of disclosure and associated stigma. All IDIs were recorded and then transcribed.

Following completion of the IDIs, participants were invited to join focus group discussions (FGDs) to further inform the content and delivery of the intervention. In a private location in the clinic, a research assistant facilitated three FGDs with a cumulative total of ten participants. FGD participants were asked to reflect on their IDI participation, including ways in which sexual trauma can impact self-esteem and relationships, coping with stress and HIV, and barriers to HIV care engagement. Each FGD included guided questions about intervention content (e.g., use of coping strategies, stigma related to HIV and sexual trauma, ongoing interpersonal violence, challenges in HIV care, and stressors encountered during ART initiation) and intervention logistics (e.g., benefits and barriers to individual or group sessions). Summary notes were reviewed in an iterative process to refine questions for subsequent FGDs.

The study team reviewed the IDI and FGD data and reached consensus on adaptations to the intervention curriculum. The resulting curriculum consisted of four individual sessions delivered by a non-specialist within a week of ART initiation, followed by two booster group sessions to increase social support, foster empowerment, and solidify intervention concepts.

Phase 3: Refining implementation through screening pre-testing and intervention trial run

To effectively implement the intervention in the clinic setting, we first developed and pre-tested a brief screening tool to see if inquiring about sexual trauma would be acceptable to patients and feasible within the clinic setting (AUTHOR et al., 2017). This tool assessed patients’ history of traumatic experiences, including sexual abuse (Bernstein et al., 2003; World Health Organization, 1990) and intimate partner violence (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). HIV clinic nurses and adherence counsellors were asked to refer all female HIV patients for screening by study staff, again with no indication that the study was focused on sexual trauma. Potential participants were those about to initiate ART or who had defaulted on ART and returned for additional adherence counselling.

For the subsequent intervention trial run, we recruited a small subset from the pool of women who had participated in the screening and endorsed a history of sexual abuse. Study staff contacted potential participants and assessed their interest in participating in a brief intervention involving individual and group sessions. The primary focus of this phase was to obtain feedback on the preliminary intervention curriculum. Thus, two waves of intervention were implemented, with nine women (n=4 and n=5, respectively) participating in the trial run. Four individual sessions were delivered over two consecutive weeks, followed by two group sessions in each of the next two weeks. The individual sessions were delivered by an isiXhosa-speaking black female psychologist trainee, and group sessions were co-facilitated by an isiXhosa-speaking black female non-specialist research assistant. isiXhosa is South Africa’s second-most widely spoken home language, and is the language of more than 90% of residents in the study community. Interventionists were trained by the study PI, supervised by the local study coordinator (a clinical psychologist), and worked collaboratively with the study team to iteratively refine the intervention. The local study coordinator observed sessions and oversaw weekly supervision and feedback sessions. The interventionist(s) completed notes after each session and conducted feedback interviews with participants after the final group session.

Results

Key informant interviews informing intervention delivery

KIIs with clinic providers offered valuable insights into the standard of care for women initiating ART in this setting, including procedures for testing, adherence counselling, and ART provision. Mental health services were limited, with the clinic psychologist (English-speaking and available one half-day per week) as the only provider. While our intervention was initially designed to be delivered by a mental health counsellor or psychiatric nurse within primary care, it was subsequently adapted for delivery by non-specialist providers under the supervision of a mental health professional due to the documented absence of specialists in this setting.

KIIs with NGO staff provided specific information about local services available to women after an assault, which informed the study’s community-based referral procedures for women seeking shelter and support. Staff also highlighted common family and community responses to assault, such as doubt or denial; barriers to reporting and disclosure including shame and stigma; and social structures contributing to high rates of assault, including gender norms that perpetuate the mistreatment of women. Similar insights about limited services and disclosure-related challenges emerged from patient IDIs and focus groups. Many women reported that trauma was even more stigmatized and difficult to disclose than HIV, particularly to providers, and consequently many had never disclosed this trauma. Women’s converging accounts of challenges in receiving social support for HIV and complex trauma, and resulting impacts on care engagement, supported the decision to include group sessions.

Patient interviews informing adaptations to intervention content

IDIs, described in detail by AUTHOR and colleagues (2017), highlighted the multiple complex traumas faced by many women in both childhood and adulthood, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. These contributed to symptoms of traumatic stress (e.g., intrusive memories, arousal, and avoidance), hindered HIV care engagement, and prevented women from effectively accessing their available social supports. Prevailing themes from patient IDIs included: (a) the lasting impacts of trauma; (b) specific barriers to engagement in HIV care; (c) personal values as motivators for care engagement; and (d) social norms and reactions surrounding trauma and HIV in the community. Experiences that reflected these themes included ongoing violence, inability to accept the HIV diagnosis, and perceived consequences of HIV disclosure, counterbalanced with the importance of children and family to achieve health. Each of the IDI themes was reflected in our preliminary intervention curriculum; however, the IDIs informed further adaptations to closely reflect the cultural and personal realities of women in this setting. For example, we incorporated a new exercise for discussing life values as motivators for HIV care engagement, in order to frame ART initiation and adherence positively and facilitate a collaborative relationship between the interventionist and participant.

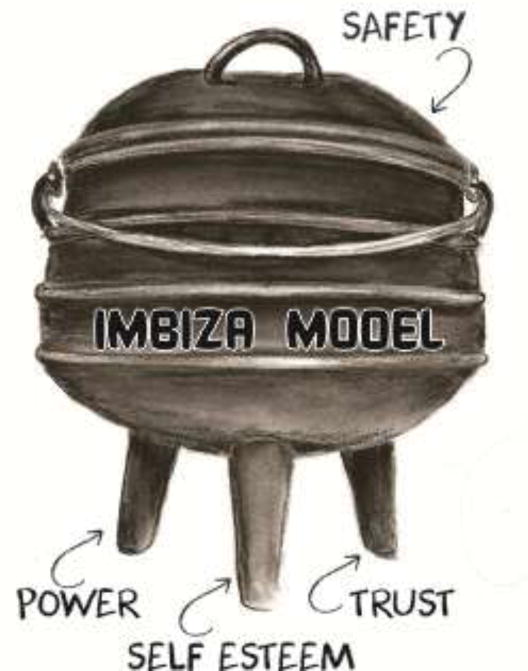

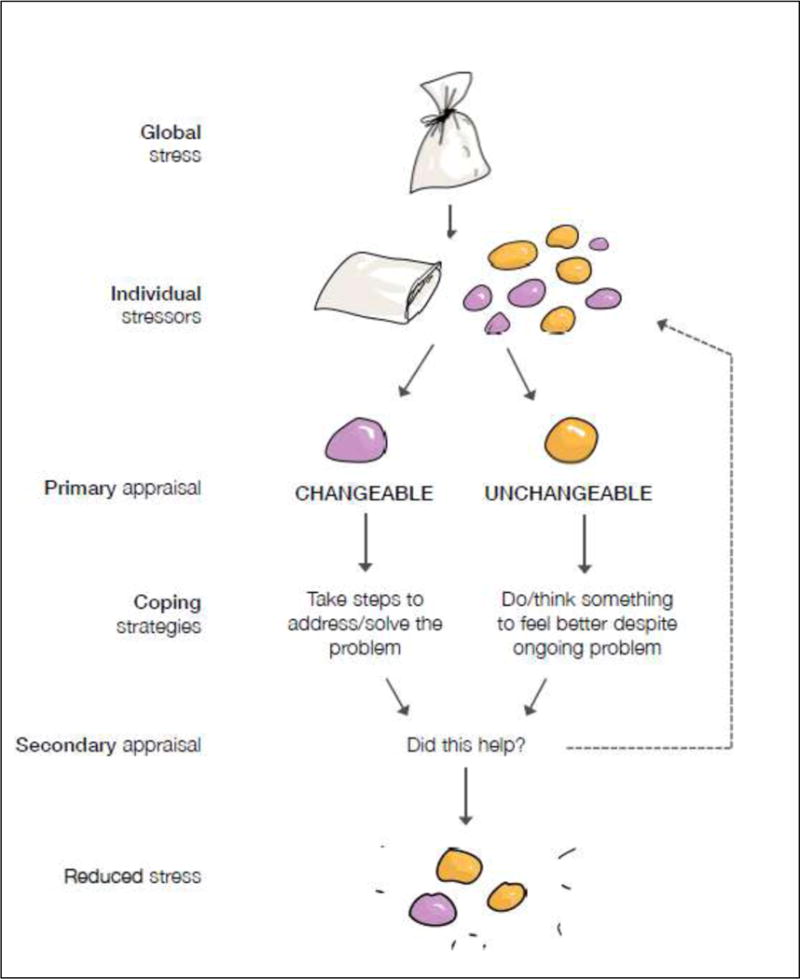

Other key intervention components (e.g., cognitive-behavioral concepts, psychological sequelae of sexual trauma, and stress and coping framework) were culturally adapted prior to the trial run. For example, acronyms previously used in LIFT (e.g., “SIPS” for safety, intimacy, power, and self-esteem) were not readily translated from English to isiXhosa. After discussing the community context with our research assistant, she recommended the image of a locally relevant object—a three-legged imbiza cooking pot—to represent these concepts. Similarly, local staff and providers noted that the decision-tree coping framework would be too complex and abstract; in response, we translated this framework into an interactive exercise with pebbles to illustrate steps of the coping process.

Resulting intervention curriculum

Feedback from formative interviews and FGDs supported a proposed combination of four core sessions of individual counselling, followed by two group sessions occurring approximately six weeks later. Sessions were designed to last approximately 60-90 minutes each. After the first session, each session begins with a review of the previous session and brief assessment of the participant’s current functioning.

Individual Session 1: Understanding the Combined Stress of Sexual Trauma and HIV

The overall goals of Session 1 are to establish rapport and begin to understand the woman’s sexual trauma history and how it may influence her HIV care. After brief orientation, the interventionist invites the participant to briefly describe her HIV history, including how she was diagnosed, her reactions, how she has coped, and her experience in initiating ART. The interventionist explains the broad goal of the intervention is to help the participant “start strong, stay strong” with ART adherence towards a lifetime of wellbeing, with a focus on reducing avoidance and developing adaptive coping skills. This theme is echoed by a poster featuring this slogan above the image of a road leading to a pleasant horizon, which remains a visual touchstone throughout the intervention. The session then shifts to a guided exploration of life values that could motivate ART adherence despite potential barriers. A “values bridge” exercise (using an actual replica of a small bridge) is used to illustrate this. The interventionist asks the participant to reflect on her life values, e.g., a desire to stay healthy and energetic, to work to make a steady income, and support her children. They then engage in interactive discussion of how ART engagement efforts would help bridge—or connect—the participant to these important life values.

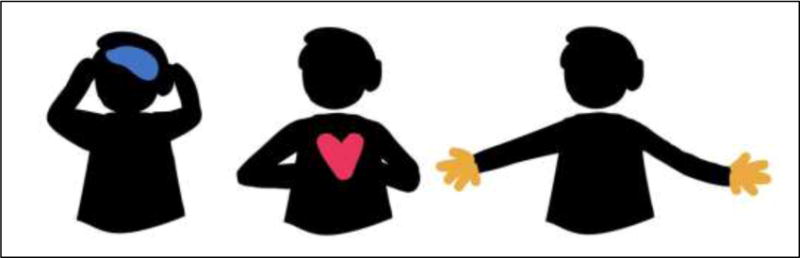

Next, participants are asked to share and explore the impact of their past trauma, using a model called “3H” (Head, Heart, Hands), shown in Figure 1 [Figure 1 near here]. This model was designed to translate traditional cognitive-behavioral models of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors into an accessible kinesthetic activity. The interventionist mimics each action shown in the diagram and uses this as a prompt to inquire about the impact of trauma in these three domains. For the thinking domain (head), the interventionist describes common cognitive symptoms of sexual trauma (e.g., anxiety or “thinking too much,” flashbacks, nightmares) and asks if participant has ever experienced or is currently experiencing any of the symptoms. For the feeling domain (heart), the interventionist shows an “emotion wheel” of locally illustrated facial expressions to help the participant begin to recognize and name emotions related to trauma. For the behavioral domain (hands), the participant focuses on her own actions as well as her interactions with others. The interventionist then uses the visual metaphor of a traditional three-legged cooking pot (imbiza) to provide a framework for areas in which her relationships might be affected following trauma. Shown in Figure 2, the three legs of power, self-esteem, and trust—and pot lid reflecting safety—of the imbiza are explained as pillars supporting vital functions (e.g., nurturance and warmth) even after a traumatic experience [Figure 2 near here]. Our formative data showed that many women have not made explicit connections between their trauma history and current symptoms, and use of this model allowed for more structured discussions of these potential impacts. Thus, Session 1 encourages awareness of the impact of past experiences, while acknowledging the possibility of ongoing trauma.

Figure 1.

The 3H (head, heart, hands) model of identifying trauma symptoms (AUTHOR et al., 2017, p.15; used with permission)

Figure 2.

The imbiza pot model (AUTHOR et al., 2017, p.18; used with permission)

Individual Session 2: Developing Strategies for Effective Coping

In Session 2, the overarching goals are to identify maladaptive coping strategies, primarily avoidant coping, and introduce a model for adaptive coping. The interventionist first leads an exploration of the participant’s HIV-related stressors (e.g., challenges with HIV disclosure, adherence, medication side effects, stigma, and the difficulty of accepting one’s diagnosis) and associated emotional consequences (e.g., shame or despair, powerlessness, hopelessness, or other symptoms of depression, anxiety, or traumatic stress). Next, the interventionist probes into the participant’s current coping methods for these HIV-related stressors. These methods may range from adaptive strategies (e.g., getting support from a friend or family member) to maladaptive ones that develop through avoidant responses to trauma (e.g., alcohol and drug use). Based on formative work, we anticipated discussion of avoidance-based strategies, including “keeping it to myself,” “trying to put it out of my head and just move on,” or self-medicating with alcohol (AUTHOR et al., 2013).

The interventionist introduces an adaptive coping framework using the “coping pebbles” activity (Figure 3). This activity translates the coping framework into a tangible analogy using a bag full of pebbles to represent the heavy burden of a diffuse global stressor. The participant is invited to identify discrete stressors by taking out individual pebbles. Different colored pebbles (purple, orange) are used to distinguish two major types of stressors—those that are changeable versus unchangeable. Once the participant identifies which type of stressor she is facing, she identifies appropriate coping strategies and ways of implementing them. For unchangeable stressors, appropriate strategies are typically emotion-focused and include acceptance, distraction, and feasible outlets for self-care and stress management. For changeable stressors, the interventionist encourages problem-focused coping strategies including active efforts to modify the stressful situation [Figure 3 near here].

Figure 3.

The coping pebbles activity (AUTHOR et al., 2017, p. 29; used with permission)

Individual Session 3: Coping and HIV Care

The overall goal of Session 3 is to connect the themes of the first two sessions: (a) the challenges of sexual trauma and HIV, and (b) applying adaptive coping strategies, including the reduction of avoidant approaches. The participant begins to set structured goals that reflect her specific barriers to adaptive coping and care engagement. At this point, the participant should be able to articulate the impact of trauma and HIV on her current functioning, understand avoidance as a common response to trauma, identify aspects of her current challenges that are changeable versus unchangeable, and list appropriate strategies for effective coping.

In the second half of the session, attention shifts to helping the participant anticipate and prepare to cope with future challenges that may arise in the context of ongoing HIV care. Our formative work suggested that this future orientation could be too theoretical, so we added a story component where the interventionist reads aloud a hypothetical narrative about Nomalizo, a woman with a complex history of trauma who encounters multiple challenges to HIV care engagement. The narrative highlights common challenges including financial, logistical, and social barriers previously described by IDI participants, and invites the participant to relate these to her own experiences. At the end of Session 3, the interventionist encourages the participant to make an action plan for addressing her specific HIV care challenges and to set an adherence-related coping goal for the week ahead.

Individual Session 4: Review and Next Steps

In Session 4, no new content is introduced. Instead, the interventionist works with the participant to consolidate concepts from previous sessions, revisit activities that were particularly challenging or seem unresolved, review goals and progress, and encourage the participant to translate her progress from sessions into daily life. The participant and interventionist review the action plan and specific goal for ART adherence identified in Session 3. If the specific goal was achieved, they discuss a plan for next steps. If the goal was not achieved, they collaboratively assess challenges encountered, consider solutions for those challenges, and set a revised goal. In both cases, they generate an updated action plan includes the participant’s goals for the upcoming group sessions, with a distinct emphasis on how those sessions can reinforce progress.

In reviewing the participant’s progress, the interventionist revisits the 3H activity in Session 4, assessing how each domain (thoughts, feelings, behaviors) may have changed over the course of the intervention. Similarly, the interventionist revisits the coping pebbles framework and goals identified in Sessions 2 and 3, reinforcing practical steps taken by the participant to reduce avoidant coping, address changeable stressors, and cope emotionally with unchangeable stressors.

Group Sessions 1 & 2: Review, Share and Reinforce

The key goal of group sessions is to reinforce insights from the individual sessions and foster engagement with women who have faced similar challenges. The interventionist(s) facilitate group sessions by encouraging open discussion, active participation, and compassionate responses to participants’ stories. Participants are encouraged to share previously identified goals and any progress or challenges in achieving them. Group sessions model social coping strategies by demonstrating the benefit of sharing one’s experience with others.

Trial run feedback on intervention content and feasibility

Trauma screening procedures were found to be acceptable given that all but one referred patients were willing to participate in the screening assessment. The 70 women screened by a female research assistant using a structured survey reported a high prevalence of trauma (51% sexual abuse; 75% physical intimate partner violence), reinforcing the need for trauma-informed intervention. Further results from this screening activity are reported elsewhere (AUTHOR et al., 2017). In the trial run, intervention logistics—including the number of sessions, their length, and combination of individual and group formats—were also well received by the participants, with no concerns expressed regarding session logistics or format. Intervention sessions were well attended (100% attended all four individual sessions and 78% attended both group sessions), supporting their feasibility.

In their feedback, participants highlighted the effectiveness of the interventionist and the intervention as a whole. Participants described substantial improvements in self-confidence, emotional state, and care engagement. As one participant noted, “my self -confidence has gained a boost and I feel powerful. Before I started with this programme I felt powerless. My stress is relieved. I feel a big relief.” All participants endorsed reductions in negative emotions, more adaptive thoughts about self and others, reengagement in supportive relationships, improved emotional coping, and active efforts to address stressors.

In response to the coping framework and psychoeducation about trauma-related sequelae, we received feedback that the visual and tactile representations of these abstract concepts were helpful and culturally salient. Almost all participants related to the values bridge exercise, which tangibly illustrated the concept of connecting one’s values to ART adherence. As one participant noted, “it really meant that I should take my ARVs in a correct way so I can be able to cross the bridge to a healthier life.” We also consistently received positive feedback on the 3H model, imbiza pot, and coping pebbles activities. The trial run interventionist wrote in her notes: “It was amazing how all participants related to the [imbiza] pot and saw it as an extension of themselves.” Regarding the coping pebbles, the interventionist noted that incorporating real pebbles helped to concretely illustrate the concepts: “They all walked out of the session knowing that they don’t have to carry one big load of a stressor, but that they can put all the stressors on the table, name them, and start implementing the coping model in their lives.”

Several women shared they had never disclosed their trauma history prior to participating in the intervention. Despite some initial hesitancy to disclose their stories, participants reported feeling that individual sessions provided a safe and comfortable environment and that group sessions facilitated disclosure through shared experiences. The interventionist documented that sessions were frequently emotional, but that participants were able to effectively manage their emotions during individual sessions and support one another productively during group sessions.

Final adaptations based on trial run feedback

While most of the adapted intervention components were perceived as beneficial and useful, concepts related to the association between trauma and HIV care engagement were found to be abstract, and the “emotion wheel” showing different expression was not highly relatable for participants. Thus, a second hypothetical narrative was developed to provide examples of emotional responses to traumatic experiences in a story format. The use of these materials, in combination with a detailed outline and sample scripts, provided guidance to the interventionist, with opportunities for individual tailoring to the participant’s trauma history and social situation.

Results also informed several key decisions regarding the delivery and implementation of ImpACT for the subsequent pilot intervention trial. First, based on formative research with clinic providers, the optimal window to provide ImpACT would be following clinic-required adherence counselling sessions to build on standard protocol and permit focus on the combined impact of sexual trauma and HIV after ART was initiated. Second, following the trial run, an interactive workbook was developed to facilitate session delivery and provide opportunities to review priority areas with individual participants, document intervention fidelity, and serve as clinical notes for documentation and supervision of both intervention content and process. Lastly, based on participant focus groups discussions, it was expected that, in addition to social support, group sessions had potential to reinforce coping skills and care engagement over time. However, following the trial run, it was noted that the first group session should occur soon after completion of the individual sessions, rather than waiting to deliver all groups as booster sessions, to build on the motivation and behavioral change that was established. Thus, the four individual sessions would be followed by one group session to facilitate social support, with two additional group sessions serving as booster sessions. The ImpACT intervention manual (AUTHOR et al., 2017) is available upon request.

Discussion

In this study, we developed ImpACT (Improving AIDS Care after Trauma), a brief coping intervention to address traumatic stress and enhance HIV care engagement among women in a low-resource, high-trauma setting in South Africa. Drawing on an evidence-based coping intervention from the United States (Sikkema et al., 2013), we engaged in an iterative formative research process to develop and tailor this intervention for delivery by non-specialists in mental health at the time of ART initiation. A pilot randomized trial is underway to assess the feasibility of this intervention and its potential to reduce traumatic stress, improve coping, and enhance care engagement (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02223390).

Several delivery modifications were made from the original intervention to improve implementation in this setting. As opposed to the 15-session LIFT protocol, our intervention consists of four individual sessions and three group sessions, since a lengthier intervention would not be feasible in a setting with limited resources dedicated to mental health treatment and high levels of complex trauma and socioeconomic stress. These decisions reflect broader trends in the implementation of mental health interventions in LMICs, including the use of shorter interventions that are integrated into health care provision and delivered by non-specialist providers (Singla et al., 2017). Future research is needed to develop and evaluate models that integrate mental health services within HIV care settings, including task sharing models for mental health service delivery.

In developing this intervention, our priority was to adapt key components of LIFT specific to the cultural and clinical context, and integrate a focus on HIV care engagement. For example, we translated the theoretical coping framework by Folkman and Lazarus, preserving its essential structure while demonstrating compatibility within the cultural context of our study site. The process of cultural adaptation has received increasing attention in recent years and involves consideration of linguistic nuance, culture-specific mechanisms of change, barriers to care, and conceptualizations of health and wellness (Kaiser et al., 2015; Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington, & Phiri, 2015). Based on themes that emerged, this intervention also began with a focus on personal values, especially caring for children, to enhance motivation for HIV care engagement. This attention to personal values motivating care is central to both models of health behavior and the “third wave” of behavioral therapies, including those intended to promote ART adherence (Daughters, Magidson, Schuster, & Safren, 2010; Moitra, Herbert, & Forman, 2011). The integration of visuals, metaphors and interactive exercises was also designed to enhance implementation by a non-specialist in mental health.

Through formative research, we learned that many women had not disclosed their sexual abuse histories, particularly not within the HIV care setting, and that a history of sexual trauma was associated with high levels of shame and stigma, potentially even more so than HIV. Meta-analyses assessing the effectiveness of psychological treatments for adult survivors of sexual trauma have observed stronger results in treatments which incorporated individual/combined models over those with group sessions only (Ehring et al., 2014). It is hypothesized that individual sessions provided the opportunity to disclose traumatic experiences and develop tailored coping skills, while group sessions focus more on therapeutic factors of group normalization of the trauma experience and stigma reduction (Ehring et al., 2014; Sayin, Candansayar, & Welkin, 2013) Thus, we determined that individual sessions were critical prior to group sessions, which would emphasize emotional support among participants and serve as booster sessions over time. Initially, many women had difficulty identifying connections between their past abuse experiences and their current coping, a phenomenon noted in previous research on HIV and trauma (Tarakeshwar et al., 2005).

A significant challenge in this study was how to adequately address multiple and complex trauma experienced by most participants, ongoing physical and sexual violence, and the need for psychiatric referrals. Even with ImpACT’s individualized components to accommodate participants’ varied experiences and perceptions of trauma, it remains challenging to address the complexity of traumatic stress and disclosure within a relatively brief intervention. Ongoing and thorough supervision is essential, particularly given the delivery of the intervention by someone not trained in psychological or psychiatric treatment. This oversight is especially important should participants require a psychological referral or evaluation for suicidality in a psychiatric hospital. Clinic staff readily acknowledged being under-resourced in addressing patients with trauma in the context of providing HIV care, and community based staff described limited availability of trauma treatment services in the community.

One limitation of this study is that intervention adaptation and implementation were conducted within a single clinic, recognizing that some delivery issues are unique to this clinic and clinics vary across settings. In addition, women recruited for the intervention trial run may have been particularly engaged and responsive, and not representative of women less comfortable with discussing sexual trauma and addressing their experiences. Lastly, participant feedback was given to the study team and the women may not have been as forthcoming with expressing concerns.

Reflecting on lessons learned

The intervention development process yielded several key lessons that proved important for the development of an intervention that is acceptable and perceived as useful to the target population, and provide insight for others approaching intervention development and cultural adaptation of existing interventions. We identify three of these lessons below.

1. Conducting formative research for practical and cross-cultural adaptation

In addition to drawing on theory and prior empirical evidence, formative research was necessary to tailor this intervention to the South African clinical and cultural context. Understanding the treatment timeline for women initiating ART allowed for intervention delivery at a critical time point, working complementary to clinic-required adherence counselling sessions, and utilizing a non-specialist provider to address the lack of mental health providers in the clinical setting.

Additionally, culturally relevant insights provided by formative work with patients and providers led to the creation of culturally-adapted exercises and visuals.

2. Tailoring the intervention to the needs of a vulnerable and complex patient population

Throughout the intervention development process, the ImpACT team recognized the unique and complex circumstances faced by women with trauma histories that both emphasized the need for an intervention, but also elucidated potential challenges for women’s successful participation. Keeping these circumstances in mind, the ImpACT team sought to: (a) create a structured intervention that could also be tailored to participants’ individual needs and trauma histories, (b) foster a safe therapeutic environment that encouraged conversations about sensitive topics, and (c) encourage repeated contact to reinforce concepts learned and promote adaptive problem solving by revisiting progress.

3. Value of pilot work to demonstrate feasibility and refine intervention for scale-up

Given the resource-limited setting and sensitive nature of the intervention content, a trial run was crucial to determining the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. In particular, the success of the small trial run supported the feasibility of using a non-specialist to deliver a coping-based mental health intervention for women with trauma histories. Furthermore, trial run feedback was important to refine the intervention structure and content for a larger pilot trial. Given these successes, future efforts at implementation will be better-informed and more likely to produce positive outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the development process for ImpACT emphasized the need to address sexual trauma among HIV-infected women, and potential for such an intervention to enhance care engagement. The adaptation process resulted in culturally relevant intervention components that could be delivered by a non-specialist in mental health and were well received by women in this context, with excellent uptake and positive feedback. Our forthcoming pilot trial on the potential effectiveness of ImpACT is expected to inform a full-scale randomized trial that represents a further step towards the implementation of effective interventions integrating mental health treatment into HIV primary care in low-resource settings.

Highlights.

We developed a coping intervention for HIV+ South African women with sexual trauma.

Formative qualitative data provided context and informed intervention content.

We describe cultural adaptations and modifications to improve delivery.

Trial run feedback supported the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant R34 MH102001. We also acknowledge support received from the Duke Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI064518), and the Duke Global Health Institute. We gratefully acknowledge Esona-sethu Ndwandwa for her assistance with the intervention, the City of Cape Town for their cooperation, and the participants who contributed time and energy to this study.

Biographies

Kathleen J. Sikkema, PhD, is the Gosnell Family Professor in Global Health and a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. She is a clinical psychologist with emphases in health and community psychology, the director of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Core in Duke’s Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), and the director of global mental health and doctoral studies at the Duke Global Health Institute. Her research program focuses on the conduct of community-based randomized, controlled HIV prevention and mental health intervention trials across a variety of populations, both in the United States and in South Africa.

Karmel W. Choi, PhD, is a Clinical and Research Fellow at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Psychiatric & Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital. She was previously a Doctoral Scholar at the Duke Global Health Institute. Her research focuses on trauma and resilience across the life course, particularly in women and their children.

Corne Robertson is a clinical psychologist in the HIV Mental Health research unit of the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health at the University of Cape Town. She works on studies on improving the health of South African women with traumatic stress in HIV care and improving HIV care engagement among pregnant women with HIV.

Brandon A. Knettel, PhD, is a postdoctoral associate in research at the Duke Global Health Institute and a licensed psychologist. His research has explored approaches for improving access to health education and mental health care in under-resourced settings, including Haiti, Tanzania, South Africa, and refugee communities in the United States.

Nonceba Ciya is a research assistant at the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health at the University of Cape Town. She works on studies on improving the health of South African women with traumatic stress in HIV care and improving HIV care engagement among pregnant women with HIV.

Elizabeth T. Knippler is a research assistant at the Duke Global Health Institute. She works on studies related to HIV care engagement, women’s health, and mental health, and serves as the coordinator for the Social and Behavioral Sciences Core of Duke’s Center for AIDS Research.

Melissa H. Watt, PhD, is an associate professor of the practice and director of the Master of Science in Global Health program at the Duke Global Health Institute. Her research focuses on understanding and addressing gender-specific health issues in sub-Saharan Africa, with specific attention to HIV, substance use, and mental health.

John A. Joska, MBChB, PhD, is an associate professor of psychiatry, head of the Division of Neuropsychiatry at Groote Schuur Hospital and director of the HIV Mental Health research unit, in the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health at the University of Cape Town. He has established a research program in neuroHIV in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. The group is interested in screening for neuro- cognitive disorders, as well as the combined effects of HIV and aging on the brain. He has a special interest in aging and the elderly, and has supervised the old age psychiatry service at Groote Schuur Hospital for more than 10 years.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27(2):169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L. Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):81–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130087016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, Watt MH, MacFarlane JC, Sikkema KJ, Skinner D, Pieterse D, Kalichman SC. Drinking in the context of life stressors: A multidimensional coping strategy among South African women. Substance Use and Misuse. 2013 doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.819365. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2013.819365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Daughters SB, Magidson JF, Schuster RM, Safren SA. ACT HEALTHY: A Combined Cognitive-Behavioral Depression and Medication Adherence Treatment for HIV-Infected Substance Users. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(3):309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Yoshihama M, Gray GE, McIntyre JA, Harlow SD. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;160(3):230–239. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Welboren R, Morina N, Wicherts JM, Freitag J, Emmelkamp PMG. Meta-analysis of psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(8):645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Chesney M, McKusick L, Ironson G, Johnson D, Coates T. Translating coping theory into an intervention. In: Eckenrode J, editor. The Social Context of Coping. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S. Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(14):2764–2789. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore-Felton C, Koopman C. Behavioral mediation of the relationship between psychosocial factors and HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):569–574. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177353e. doi: PSY.0b013e318177353e [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stockl H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids. 2015;29(16):2183–2194. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack H, Wagner RG, Petersen I, Thom R, Newton CR, Stein A, Hofman KJ. Closing the mental health treatment gap in South Africa: a review of costs and cost-effectiveness. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23431. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, Garrido-Cumbrera M, Seedat S, Mari JJ, Saxena S. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet. 2007;370(9592):1061–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(7):1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, Ratsaka M, Schrieber M. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. South African Medical Journal. 2001;91(5):421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser BN, Haroz EE, Kohrt BA, Bolton PA, Bass JK, Hinton DE. “Thinking too much”: A Systematic review of a common idiom of distress. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;147:170–183. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- LeGrand S, Reif S, Sullivan K, Murray K, Barlow ML, Whetten K. A Review of Recent Literature on Trauma Among Individuals Living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(4):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0288-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Fitzgerald H. Treating Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Among People Living with HIV: a Critical Review of Intervention Trials. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(9):83. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0724-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Drabkin AS, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Reductions in alcohol and cocaine use following a group coping intervention for HIV-positive adults with childhood sexual abuse histories. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1942–1951. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra E, Herbert JD, Forman EM. Acceptance-based behavior therapy to promote HIV medication adherence. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1660–1667. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.579945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S, Kingdon D, Pinninti N, Turkington D, Phiri P. Cultural adaptation of CBT for serious mental illness: A guide for training and practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sayin A, Candansayar S, Welkin L. Group psychotherapy in women with a history of sexual abuse: what did they find helpful? J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(23-24):3249–3258. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat M, Van Niekerk A, Jewkes R, Suffla S, Ratele K. Violence and injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an agenda for prevention. The Lancet. 2009;374(9694):1011–1022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60948-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S. Interventions to improve psychological functioning and health outcomes of HIV-infected individuals with a history of trauma or PTSD. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2012;9(4):344–350. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Wilson PA, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Neufeld S, Ghebremichael MS, Kershaw T. Effects of a coping intervention on transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS and a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(4):506–513. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Ranby KW, Meade CS, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, Kochman A. Reductions in traumatic stress following a coping intervention were mediated by decreases in avoidant coping for people living with HIV/AIDS and childhood sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(2):274–283. doi: 10.1037/a0030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Joska JA, Choi KW, Robertson C, Ciya N, Knettel BA, Watt MH, Knippler ET, Elliott SA, ImpACT Project Team . ImpACT: Improving AIDS care after Trauma–Intervention Manual. Duke University and University of Cape Town; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological Treatments for the World: Lessons from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:149–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The impact of DSM-IV mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2119–2143. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Takuva S, Brown AE, Pillay Y, Delpech V, Puren AJ. The continuum of HIV care in South Africa: implications for achieving the second and third UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. Aids. 2017;31(4):545–552. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000001340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Fox A, Ferro C, Khawaja S, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. The connections between childhood sexual abuse and human immunodeficiency virus infection: Implications for interventions. J Community Psychol. 2005;33(6):655–672. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Prevention Gap Report. 2016. Retrieved from Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Meera SM, Pian J, Patel V. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11. 2013. Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries; p. Cd009149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velloza J, Watt MH, Choi KW, Abler L, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, Sikkema KJ. HIV/AIDS-related stigma in South African alcohol-serving venues and its potential impact on HIV disclosure, testing and treatment-seeking behaviours. Glob Public Health. 2015;10(9):1092–1106. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.1001767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Dennis AC, Choi KW, Ciya N, Joska JA, Robertson C, Sikkema KJ. Impact of Sexual Trauma on HIV Care Engagement: Perspectives of Female Patients with Trauma Histories in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(11):3209–3218. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1617-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Llabre MM, Duran RE, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Penedo FJ, Schneiderman N. A stress and coping model of medication adherence and viral load in HIV-positive men and women on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):385–392. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.385. doi: 2005-07929-007 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI), Version 1.0. Geneva: WHO; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yemeke TT, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Ciya N, Robertson C, Joska JA. Screening for traumatic experiences and mental health distress among women in HIV care in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0886260517718186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260517718186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]