Abstract

Child maltreatment can have a lasting impact, which is why it is important to understand factors that may exacerbate or mitigate self-esteem difficulties in adulthood. Although there is tremendous benefit that can come from religion and spirituality, few studies examine religious views after child maltreatment. Subsequent interpersonal difficulties may also affect self-esteem in maltreatment survivors. This study sought to examine interpersonal problems and religiosity as mediators in the link between childhood maltreatment and self-esteem in adulthood. The study recruited 718 women (M = 19.53 years) from a large public university. Participants completed questionnaires related to child abuse and neglect, interpersonal problems, religiosity, and self-esteem. Results demonstrated that all forms of maltreatment were associated with negative views of God and with more interpersonal difficulties. Viewing God as a punishing figure mediated the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and low adult self-esteem, along with several areas associated with interpersonal problems. Further, for both child emotional neglect and physical abuse, viewing God as less supportive mediated the relationship between child maltreatment and low adult self-esteem. The results may help in intervention for child maltreatment survivors by increasing awareness of the importance of religiosity in treatment to self-esteem issues in both childhood and adulthood.

Child maltreatment remains a public health issue in the United States and throughout the world. In 2012, 3.4 million child referrals to child protective services occurred for some form of child abuse or neglect (CDC, 2014). Child neglect and emotional abuse are the most common types of child maltreatment, with 78% of reported child survivors in 2012 being cases of neglect (CDC, 2014). Historically, however, emotional abuse and neglect are the least studied (DePanfilis, 2006), whereas child physical and sexual abuse are examined more often. All forms of child maltreatment include both short and long-term difficulties, such as low self-esteem, interpersonal problems, higher revictimization rates, health problems, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Anonymous, 2017; Borger, Cox, & Asmundson, 2005; Jumper, 1995; Kim & Cicchetti, 2006). The current study focuses on maladaptive self-views among individuals who experienced child maltreatment and examine whether the link between child maltreatment and low self-esteem may be explained by disrupted social and divine relations, represented by interpersonal problems and religiosity, respectively. In particular, religious individuals may construct divine relations, engaging a divine other in a quest for solace and guidance (Ellison, 1991), which are likely to bolster their sense of personal meaning, religious identity, and moral commitments (Furrow, King, & White, 2004).

Cole and Putnam (1992) noted that child abuse disrupts both the “self” and “other.” That is, child maltreatment causes self-esteem difficulties, affect problems, and behavioral issues. Additionally, child abuse interferes with the ability to form social bonds, usually because of trust issues. In fact, exposure to any form of trauma will have a negative effect on interpersonal functioning (Beck, Grant, Clapp, & Palyo, 2009). Cicchetti and Toth (2005) found that early maltreatment could damage healthy attachments and social processing. With the once healthy attachments gone, there may now be pervasive social disruption throughout the lifespan. Briere and Rickards (2007) found that child sexual abuse significantly predicted a significantly altered self-identity as well as relatedness issues, linked to increased idealization-disillusionment, abandonment concerns, susceptibility to influence and affect dysregulation. Child sexual abuse was also found to disrupt the ability to generate realistic appraisals of the self and of others, hindering the ability to form accurate and whole images of the self and others (Callahan & Hilsenroth, 2005). Moreover, there is a link between childhood sexual abuse and deficient romantic relationship formation as well as difficulty with sexual functioning in adolescence and adulthood (Beitchman et al., 1992). Abused children will likely have poorer social relationships, poorer sexual relationships, and more interpersonal conflicts when compared to non-abused peers (Kim & Cicchetti, 2010; Watkins & Bentovim, 1992). Clearly, child maltreatment may result in interpersonal problems, which in turn may impede the development of positive views of self.

In the extant child maltreatment literature, religiosity has been identified as a crucial protective factor against the detrimental effects of child maltreatment (Kim, 2008). Religiosity is defined as a number of dimensions related to religious beliefs and involvement in religious practices (Bergan & McConatha, 2000). This could include one’s views of God or a higher power. Religion has a major role in American life, with approximately 82% of Americans saying that religion had a degree of importance in their lives (Pew, 2013). Relevant to the trauma literature, an increase in religiosity may protect trauma survivors from shattered assumptions and difficulties associated with trauma and victimization (Kulie & Ehring, 2014). Indeed, it was found that higher religiosity produced fewer trauma symptoms, even when controlling for perceived social support (Harris, Erbes, Engdahl, Winskowski & Nguyen, 2014).

Although religiosity seems to have beneficial effects for adjustment in child maltreatment survivors, prior research has reported that individuals experiencing child maltreatment are less likely to practice religion. Such findings may be explained by the correspondence hypothesis (Granqvist & Dickie, 2005), which proposes that individuals who have experienced secure vs. insecure childhood attachments have established the foundations on which a corresponding relationship with God could be built. According to this view, maltreated individuals, who are more likely to have insecure attachment relationships with their primary attachment figures, are less likely to view God as loving and caring compared to nonmaltreated individuals. In contrast, the compensation hypothesis (Granqvist & Dickie, 2005) predicts that individuals with insecure childhood attachment may be more likely to seek God for compensatory attachment relationships. Consistent with the correspondence hypothesis, empirical studies have reported negative effects of child maltreatment on religiosity demonstrating that survivors of abuse tend to have more negative views on God (e.g., Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1989; Kennedy & Drebing, 2002). In particular, Bierman (2005) examined the effects of physical and emotional abuse on religiosity among adults and found that abuse perpetrated by fathers during childhood was related to low levels of religiosity. It is plausible that the image of God as a father led survivors of abusive fathers to distance themselves from religion. However, there is also evidence that maltreated and nonmaltreated children did not differ in their view of God as kind and close, although maltreated children perceived their parents as less kind and more wrathful than did nonmaltreated children (Johnson & Eastburg, 1992). Work is needed to understand the unique role of religiosity in child maltreatment survivors.

Current Study

Despite the potential benefits of religiosity, relatively few studies have examined religiosity after child maltreatment. In addition, previous research has primarily focused on physical and sexual abuse and studies examining the impact of child emotional abuse and neglect are rare. Considering the lasting impact of child maltreatment, it is important to understand factors that may exacerbate or mitigate self-esteem difficulties. This study sought to examine interpersonal problems and religiosity—representing social and divine relations, respectively—as mediators in the relationship between child abuse and neglect and self-esteem in adult women. Women were used due to the higher rates of child sexual abuse and comparable rates of child physical abuse when compared to men (Briere & Elliott, 2003). It was expected that various forms of child abuse and neglect would predict lower adult self-esteem and that this relationship would be explained by individual differences in interpersonal problems and religiosity.

Method

The current study included 718 women at a large public university (Mean Age = 19.53 years, SD = 1.84). The women reported their ethnicity/race as Caucasian (80.8%), Asian (9.7%), African-American (3.5%), Hispanic (2.8%), Other (2.4%), and Unreported (0.8%). Participants reported their religion as Protestants (32.7%), Roman Catholics (25.5%), Jewish (1.67%), Muslim (1.25%), None (21.0%), and Unreported (17.8%).

Measures

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 2003)

The CTQ is a 25-item inventory of five types of childhood trauma: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. The CTQ uses a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Never True) to 5 (Very Often True), with scores summed. Each subscale consists of 5 items, with higher scores indicating greater child maltreatment within the specific domain. The definition of child abuse is consistent with federal guidelines described in the Child Welfare Information Gateway (2013). Specifically, physical abuse involves non-accidental physical injury as a result of punching, beating, kicking, biting, shaking, throwing, stabbing, choking, hitting, burning, or otherwise harming a child that is inflicted by a parent, caregiver, or other person who has responsibility for the child (p. 2). Sexual abuse includes activities by a parent or caregiver such as fondling a child’s genitals, penetration, incest, rape, sodomy, indecent exposure, and exploitation through prostitution or the production of pornographic materials (p. 3). Emotional abuse involves a pattern of behavior that impairs a child’s emotional development or sense of self-worth, including constant criticism, threats, or rejection (p. 4). Neglect is defined as the failure of a parent, guardian, or other caregiver to provide for a child’s basic needs (p. 3). Cronbach’s alphas for the current study were: .87 for Emotional Abuse, .90 for Emotional Neglect, .75 for Physical Abuse, .66 for Physical Neglect, and .95 for Sexual Abuse.

Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (Fetzer Institute National Institute on Aging, 1999)

The Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality is a 27-item measure of beliefs and relationships with a higher power as well as connection to individuals within a religious or spiritual setting. This measure was developed and has been used to examine key dimensions of religiousness/spirituality as they relate to physical and mental health outcomes in the general population. Importantly, it has also been used in people who do and do not believe in a higher power (based on their responses on their ratings). The participants were asked to rate each item based on how they handle life problems from a religious point of view on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (A great deal) to 4 (Not at all). Scores were summed, with higher scores meaning higher scores on the subscales. For the purposes of this study, two subscales were examined. These included viewing God (or a higher power) with positive feelings and as supportive and helpful (7-items; e.g., “I look to God for strength, support, and guidance in crises) or viewing a higher power with negative feelings (2-items; e.g., “I wonder whether God has abandoned me”). Cronbach’s alphas for the current study were: .90 for God as Positive and .71 for God as Negative.

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Pilkonis, Kim, Proietti, & Barkham, 1996)

The IIP is a 47-item measure of common interpersonal problems that the respondent may experience. The participants were asked to rate how characteristic each item is of them on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all distressing) to 4 (extremely distressing), with higher scores summed to indicate more interpersonal problems. The questionnaire has been validated with a non-clinical college sample (Anonymous, 1999), demonstrating high internal consistency (α = .90), strong test-retest reliability and good convergent and external validity. The IIP items are presented as either forms of inhibitions or excesses. For example, an inhibition question includes “It is hard for me to really care about other people’s problems,” while an excess question includes “I try to please other people too much.” Items on the scale are summed, with higher scores indicating greater interpersonal deficiencies. The IIP consists of five domains of interpersonal difficulties: aggression (hostility towards others), ambivalence (difficulty collaborating with others), sensitivity (reactivity towards others), need for approval (anxiety and concern about evaluation from others), and lack of sociability (distress and difficulty related to socializing). The Cronbach’s alphas for the current study were: .86 for Aggression (7 items), .82 for Ambivalence (10 items), .85 for Sensitivity (11 items), .87 for Need for Approval (9 items), and .90 for Lack of Sociability (10 items).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965)

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a 10-item scale that measures self-worth and self-esteem. Items are answered on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 3 (Strongly agree) and summed with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was .91.

Procedure

This study was conducted as part of a larger study examining different physiological and immunological variables associate with child and adult abuse. The current study involved several online questionnaires administered through a confidential psychology department experiment management system, before participants returned to the laboratory for the larger study. The total time to complete the questionnaires was not more than one hour, with most participants completing the survey in thirty minutes. Participants were encouraged to take breaks as needed to help prevent fatigue. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the current study. Participants were compensated with extra credit points allotted toward their psychology courses. Further, participants were provided with instructions on how to seek mental health support if needed.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

The means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations for all variables of interest are presented in Table 1. All child maltreatment variables were significantly positively correlated with the IIP subscales and with God as Negative, and significantly negatively correlated with self-esteem score.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics: Means, standard deviations (SD), and inter-correlations for all variables of interest (N = 718)

| Correlations | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

| 1. Child Emotional Abuse | 7.56 | 3.56 | - | |||||||||||

| 2. Child Physical Abuse | 6.00 | 2.10 | .60** | - | ||||||||||

| 3. Child Sexual Abuse | 5.45 | 2.10 | .34** | .34** | - | |||||||||

| 4. Child Emotional Neglect | 7.11 | 3.25 | .74** | .49** | .29** | - | ||||||||

| 5. Child Physical Neglect | 5.65 | 1.64 | .49** | .42** | .33** | .55** | - | |||||||

| 6. God as Negative | 2.68 | 1.12 | .18** | .17** | .15** | .13** | .16** | - | ||||||

| 7. God as Positive | 18.15 | 5.97 | −.08* | .02 | −.02 | −.13** | −.12** | −.07 | - | |||||

| 8. IIP Aggression | 4.45 | 4.53 | .31** | .23** | .16** | .22** | .15** | .26** | −.04 | - | ||||

| 9. IIP Ambivalence | 6.05 | 5.03 | .30** | .22** | .16** | .27** | .20** | .25** | −.03 | .61** | - | |||

| 10. IIP Sensitivity | 12.99 | 7.57 | .35** | .20** | .13** | .27** | .17** | .25** | −.07 | .60** | .53** | - | ||

| 11. IIP Need for Approval | 13.75 | 7.35 | .20** | .12** | .08* | .16** | .15** | .20** | −.06 | .23** | .26** | .70** | - | |

| 12. IIP Lack of Sociability | 8.24 | 7.14 | .30** | .18** | .17** | .28** | .21** | .23** | −.13** | .41** | .50** | .67** | .63** | - |

| 13. Self-Esteem | 21.94 | 5.56 | −.36** | −.23** | −.10** | −.37** | −.21** | −.26** | .17** | −.31** | −.30** | −.60** | −.52** | −.59** |

Note. IIP = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems

p < .05,

p < .01.

Mediation

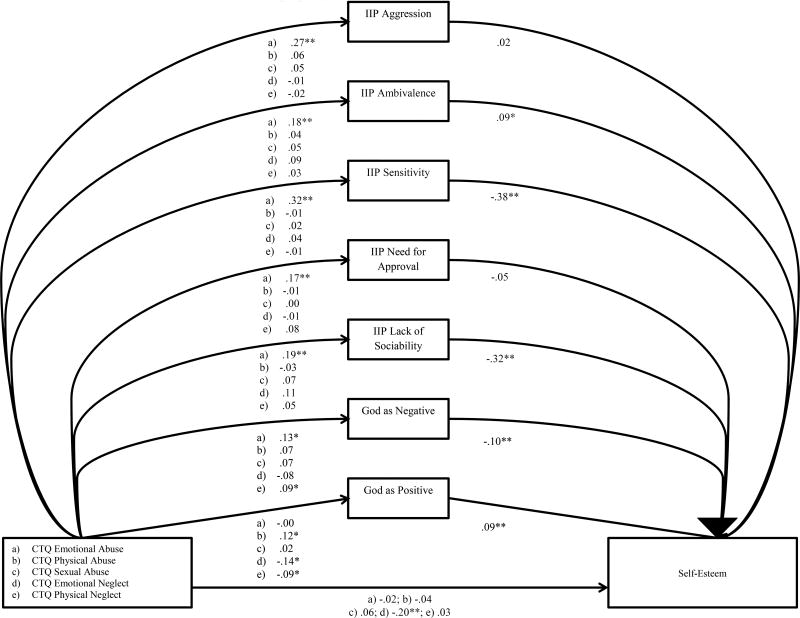

The relationships between the predictors, mediators, and outcomes are shown in Figure 1 using linear regression analyses. Given limitations using the causal steps of mediation (see MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002), mediation was confirmed using MEDIATE (Hayes & Preacher, 2013). Linear regression analyses without mediators showed significant relationships between two of the predictors and outcomes (Emotional Abuse: β = −.18, p < .01; Physical Abuse: β = −.02, p = .70; Sexual Abuse: β = .03, p = .41; Emotional Neglect: β = −.23, p < .01; Physical Neglect: β = .00, p = .96). The results of mediation analyses estimating associations between the predictors and each of the mediators as well as the mediators and the outcome are presented in Figure 1. After accounting for the mediators, the relationship between the predictors and outcomes became non-significant (Emotional Abuse: β = −.02, p = .71; Physical Abuse: β = −.04, p = .26; Sexual Abuse: β = .06, p = .07; Emotional Neglect: β = −.20, p < .01; Physical Neglect: β = .03, p = .35) which demonstrated that for emotional abuse and self-esteem, mediation was supported for God as Negative, IIP Ambivalence, IIP Sensitivity, and IIP Lack of Sociability.

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients for the link between the Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and self-esteem as mediated by the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) subscales and views of God. *p < .05; **p < .01.

As shown in Table 2, mediation analyses using the software macro, MEDIATE (Hayes & Preacher, 2013) produces various tests of total, direct, and indirect effects of variables, including an omnibus test for the relationship between the independent variables (i.e., abuse type) and the dependent variable (self-esteem), omnibus tests for the mediator in the model (i.e., IIP and religiosity), and bootstrap (1000 samples) confidence intervals for indirect effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). If this interval does not contain 0, the indirect effect through the mediator is significant. Bootstrapping is the preferred methods for testing mediation, in comparison to the Sobel test or the classic causal steps approach, due to appropriate Type I error rates and increased power (MacKinnon et al., 2002; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004).

Table 2.

Regression analyses testing views of God and interpersonal problems as mediators between child abuse type and self-esteem

| B | SE (B) | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome- Self-Esteem | ||

| Predictors- | ||

| CTQ Emotional Abuse | −.28** | 0.09 |

| CTQ Physical Abuse | −.04 | 0.12 |

| CTQ Sexual Abuse | 0.08 | 0.1 |

| CTQ Emotional Neglect | −.40** | 0.09 |

| CTQ Physical Neglect | 0.01 | 0.15 |

|

| ||

| Predictors- | ||

| CTQ Emotional Abuse | −.03 | 0.07 |

| CTQ Physical Abuse | −.10 | 0.09 |

| CTQ Sexual Abuse | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| CTQ Emotional Neglect | −.34** | 0.07 |

| CTQ Physical Neglect | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| IIP Aggression | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| IIP Ambivalence | .13** | 0.04 |

| IIP Sensitivity | −.25** | 0.04 |

| IIP Need for Approval | −.05 | 0.03 |

| IIP Lack of Sociability | −.23** | 0.03 |

| God as Negative | −.47** | 0.14 |

| God as Positive | .07** | 0.03 |

Note. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; IIP = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems.

p < .05;

p < .01.

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, when examining direct relations between maltreatment types and self-esteem, Emotional Abuse (b* = −.28, p < .01) and Emotional Neglect (b* = −.40, p < .01) were significant predictors of self-esteem [F(5,712) = 25.36, p < .01, R2 = .15]. When the mediators were added to the model predicting self-esteem, the full model remained significant, [F(12, 705) = 55.84, p < .01, R2 = .49]. Specifically, God as Negative (b* = −.47, p < .01), God as Positive (b* = .07, p < .01), IIP Ambivalence (b* = .13, p < .01), IIP Sensitivity (b* = −.25, p < .01), and IIP Lack of Sociability (b* = −.23, p < .01) were significantly associated with self-esteem. The direct effect of Emotional Neglect (b* = −.34, p < .01) remained significant, whereas the direct effect of Emotional Abuse (b* = −.03, p = .71) was no longer a significant predictor.

Examination of the 95% confidence interval revealed significant indirect effects for Emotional Abuse via God as Negative (−.048 to −.002), IIP Ambivalence (.005 to .065), IIP Sensitivity (−.258 to −.101) and IIP Lack of Sociability (−.154 to −.026). Specifically, more negative views of God, lower levels of ambivalence, and higher levels of lack of sociability and sensitivity in interpersonal relationships explained the association between Emotional Abuse and low self-esteem. In addition, for Emotional Neglect and Physical Abuse, God as Positive was a significant mediator (.002 to .060 for Physical Abuse and −.046 to −.002 for Emotional Neglect), suggesting that the association between Physical Abuse and Emotional Neglect were related to more and less positive views of God, respectively, which was related to higher self-esteem.

Discussion

This study sought to examine the role of religiosity and interpersonal problems as mediators in the relationship between child abuse/neglect experiences and self-esteem in adulthood. Results indicated that emotional neglect and emotional abuse were significant direct predictors of self-esteem. When examining the full model including the mediators, Emotional Neglect was still significant but Emotional Abuse was no longer a significant predictor of self-esteem. Emotional Neglect, IIP Sensitivity, IIP Lack of Sociability, and God as Negative predicted lower self-esteem while IIP Ambivalence and God as Positive predicted higher self-esteem.

We found that only Emotional Abuse and Emotional Neglect initially predicted lower self-esteem, after controlling for the effects of Sexual Abuse, Physical Abuse, and Physical Neglect. Our finding emphasizes that emotional abuse and neglect have powerful effects on adverse outcomes above and beyond other forms of abuse. In addition, after the inclusion of social and divine mediators, Emotional Abuse was no longer a significant predictor of self-esteem, implying that viewing of God as negative and having interpersonal problems may be prominent factors that explain why emotional abuse survivors are likely to have lower views of self. This finding highlights the importance of evaluating these factors in survivors of emotional abuse.

Prior research is not unequivocal regarding the prominent role of emotional maltreatment for self-esteem development, however. For example, Bolger and associates (1998) found that children who experienced chronic sexual and physical abuse showed lower self-esteem compared to those with the other subtypes. In contrast, Kim and Cicchetti (2006) found that experiences of emotional abuse were stronger predictors of low self-esteem and depression than physical abuse among maltreated children. Similarly, Spinazzola and colleagues (2014) studied children and adolescents and reported that psychologically maltreated youth often had greater baseline levels of behavioral issues and other symptoms than physically or sexually abuse youth. Further, they found that having psychological maltreatment (e.g., emotional abuse) in childhood was related to worse outcomes. Extending this line of research, our results indicate prominent long-term effects of emotional maltreatment on self-esteem evidenced among young adult females.

Another possible reason that Emotional Abuse and Emotional Neglect are more significantly related with self-esteem than sexual and physical abuse could be that the child feels intentionally targeted by their caregiver, who is supposed to support and love them. Emotional abuse may include constant criticism or blame direct toward the child, threatening the child with violence or abandonment, and not providing a safe environment for the child. These actions take a toll on the core of the child’s self-esteem, especially if such abuse comes from their parents. Their own parents, who view them as nuisances and want no part in their lives, tarnish the child’s sense of self-worth and accomplishments. Other forms of child abuse (e.g., sexual abuse, physical neglect, and physical abuse) may influence self-esteem, but once we controlled for the emotional aspects, the relative contributions of other forms of child maltreatment were notably reduced, implying that the core underlying mechanism involves the emotional impact of these acts. Importantly, all forms of maltreatment were inter-correlated. While we statistically controlled for variance across forms, it is also likely that emotional abuse and emotional neglect were present throughout and could underlie negative outcomes across all forms of maltreatment. Various views of God appear to mediate the experience of emotional maltreatment on self-esteem in adulthood. Emotional Abuse was mediated through God as more negative, while Emotional Neglect was mediated through God as less positive. This finding suggests that for emotional maltreatment involving commission (e.g., the infliction of emotional harm) induces negative images of God. Conversely, emotional maltreatment involving omission (e.g., failure to meet emotional needs) prevents positive images of God. Specifically, the finding of the associations of Emotional Abuse and Neglect with more negative and less positive views of God provides evidence supporting the correspondence hypothesis (Granqvist & Dickie, 2005), indicating that insecure attachment to parents caused by emotional maltreatment is likely to have similar attachment to God, make the maltreated individuals to see God as aloof, unsupportive, and unloving. The finding of the link between Emotional Abuse and negative views of God is consistent with a previous study of female college students that reported that survivors of childhood emotional and sexual abuse were more likely to have negative views of God and were less likely to derive their feelings of self-worth through the belief that they were loved, valued, and unique in the eyes of God, and they are less likely to have their self-esteem contingent upon God’s love (Kim & Williams, 2009). The current study further found that emotional neglect was related to less positive views of God. For those who are emotionally neglected, children’s sense of self-worth may become tarnished by a lack of support and they may also begin having doubts that any help will come. They may not expect any help, including from a higher power. The child may begin to believe that they truly are worthless, useless, and pitiful and would not turn to a higher power due to disbelief that external help will come.

In contrast, regression analyses demonstrated that Physical Abuse was associated with more positive views of God which were in turn related to higher self-esteem. The unexpected positive association between Physical Abuse and positive views of God might have been a suppression effect (when controlling for other types of child maltreatment), given that the zero-order correlation between Physical Abuse and positive views of God was not significant (see Table 1). If replicated, this finding can be interpreted as evidence to support the compensation hypothesis (Granqvist & Dickie, 2005), suggesting that individuals with insecure attachment to physically abusive parents may be more likely to seek relationship with God, as a substitute attachment figure, for compensating for deficient caregiving bonds. The diverging associations between Emotional Abuse vs. Physical Abuse in relation to the views of God seem to reflect the nature of the abuse experiences. Compared to experiencing physical injuries by aggressive parents, experiencing parents’ persistent thwarting of emotional needs for psychological security, acceptance, and positive regard may make it harder for the abused children to seek God as a comforting figure.

An important finding is the role of interpersonal ambivalence significantly mediating the relationship between emotional abuse and self-esteem, but being predictive of higher self-esteem. Conversely, lack of sociability and high sensitivity were significant mediators and predicted lower self-esteem. These differences may be related to the nature of the different aspects of interpersonal difficulties, in that sensitivity is a measure of strong reactions to others and lack of sociability is related to experiencing distress in the presence of others (Pilkonis, Kim, Proietti, & Barkham, 1996). Interpersonal ambivalence is related to instability in relationships. Inconsistent or unstable attachments with others may be a consequence of emotional abuse, but the interpersonal issues seem to function differentially among these individuals with emotional abuse experiences. The tendency to be ambivalent in interpersonal relationships may reflect their being extremely cautious with trusting others, and such discernment may work beneficially for them to be selective in relationships in which they may feel valued thus resulting in thinking more positively about themselves.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the study that should be noted. First, this study was cross-sectional in nature. Participants were asked to retrospectively report their child abuse experiences and such retrospective reports could have been biased due to lack of knowledge, poor memory, and careless reports. Considering the sensitive nature of the questions asked, participants may not have been responding truthfully in order to come across in a more socially appropriate way. Second, causal relationships cannot be verified in our findings, given the nature of our cross-sectional and correlational data. It should be noted, however, that time precedence was implied based on the nature of the questions being asked (i.e., report on childhood abuse and report on current self-esteem). Our hypothesized mediation model was established based on theoretical views on the effect of child maltreatment on views on God (the correspondence vs. compensation hypotheses) and the existing evidence indicating significant roles of views on God and interpersonal relationships in contributing to self-esteem. Future studies should employ more rigorous testing prospective associations among the predictors (child maltreatment subtypes), the mediators (views on God; interpersonal relationships), and the outcome (self-esteem). Third, while this study focused solely on child maltreatment, child maltreatment is one of several factors that can influence one's religious views and interpersonal relationships. In particular, future studies should consider examining other important life experiences, including trauma and loss. Other psychological constructs (e.g., depression) would also be important to examine, as these may influence the associations among child maltreatment, divine and interpersonal relations, and self-esteem. Finally, the use of a college sample limits the applicability to women outside of the college population. The use of only women may also limit the findings. Future studies should examine a variety of populations and genders.

Future Directions and Implications

In closing, the results of this study highlight the importance of religious views and interpersonal problems, especially sensitivity to others and lack of sociability, in the relationship between child maltreatment experiences and adult self-esteem. The findings may help inform treatments by increasing awareness of the importance of religiosity and mitigating interpersonal risk factors to help with views of self. In particular, in addition to targeting interpersonal distress, clinicians can aim to explore already-existing views of God with their clients and how current religious experiences may contribute to their self-views. Moreover, the emotional impact of any maltreatment experience would be important to address, including a sense of betrayal or mistrust of the parent-figure and its effect on both social outcomes and self-worth. Clinicians could help examine client’s interpersonal reactions and teach skills to improve relationships and relationship quality. Further, religious leaders and groups could benefit from these findings, as people may turn to their religious communities rather than mental health professionals (see Hayward & Krause, 2014). It would be apt to encourage individuals to utilize resources available to them both within a religious organization and outside of it. An interesting line of future investigation in clients who value religiosity would be to explore how changing views of God to be more positive and less punitive might have beneficial effects on self-esteem in survivors. In sum, this study suggests that childhood emotional abuse and neglect have powerful long-term effects on self-esteem in young adult female survivors, and the link between emotional abuse and negative outcome may be explained via social and divine mediators that can have therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DA036017 to Kim-Spoon) and from Virginia Tech Institute for Society, Culture, and Environment (to Scarpa and Kim-Spoon).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beck JG, Grant DM, Clapp JD, Palyo SA. Understanding the interpersonal impact of trauma: Contributions of PTSD and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Zuker KJ, Hood JE, DaCosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1991;16:101–118. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergan A, McConatha JT. Religiosity and life satisfaction. Activities, Adaptation and Aging. 2000;24(3):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman A. The effects of childhood maltreatment on adult religiosity and spirituality: Rejecting God the father because of abusive fathers? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69:1171–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borger SC, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJG. PTSD and other mental health problems in adults who report histories of physical abuse and neglect. In: Corales TA, editor. Trends in posttraumatic stress disorder research. Hauppauge, NY: Nove Science Publishers; 2005. pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliot DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-report childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27:1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere JB, Rickards S. Self-awareness, affect regulation, and relatedness: Differential sequels of childhood versus adult victimization experiences. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(6):497–503. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31803044e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan KL, Hilsenroth MJ. Childhood sexual abuse and adult defensive functioning. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193(7):473–479. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000168237.26124.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Injury Prevention & Control: Division of Violence Prevention. Child maltreatment: facts at a glance. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. What is child abuse and neglect? Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Putnam FW. Effect of incest on self and social functioning: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:174–184. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePanfilis D. Child Abuse and Neglect User Manual Series. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. Child neglect: A guide for prevention, assessment, and intervention. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG. Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1991;32(80–99) doi: 10.2307/2136801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute and National Institute on Aging. A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo, Michigan: John E. Fetzer Institute; 1999. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling GT, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse and its relationship to later sexual satisfaction, marital status, religion, and attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1989;4:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. The sexual victimization of college women 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Mullen PE, Sibthorpe B, Bammer G. The long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse in Australian women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23:145–159. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furrow JL, King PE, White K. Religion and positive youth development: Identity, meaning, and prosocial concerns. Applied Developmental Science. 2004;8:17–26. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0801_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P, Dickie JR. Attachment and Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence. In: Roehlkepartain EC, King PE, Wagener LM, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JI, Erbes CR, Engdahl BE, Winskowski AM, Nguyen XN. Social support as a mediator in the relationship between religious comforts and strains and trauma symptoms. Journal of Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2014;6:223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaard JJ. The challenge of defining child sexual abuse. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1036–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable [White paper] 2013 doi: 10.1111/bmsp.12028. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hayward RD, Krause N. Religion, mental health and well-being: Social aspects. In: Saroglou V, editor. Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior. New York: Psychology Press; 2014. pp. 255–280. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BW, Eastburg MC. God, parent and self concepts in abused and nonabused children. Journal of Psychology and Christianity. 1992;11:235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Jumper SA. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to adult psychological adjustment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1995;19:715–728. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P, Drebing CE. Abuse and religious experience: A study of religiously committed evangelical adults. Mental Health, Religion and Culture. 2002;5:225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. The protective effects of religiosity on maladjustment among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.011. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self-system processes and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development. 2006;77:624– 639. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Williams SR. Linking childhood maltreatment to substance use in college students: The mediating role of self-worth contingencies. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma. 2009;18:88–105. doi: 10.1080/10926770802616399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulie HT, Ehring T. Predictors of Changes in Religiosity After Trauma: Trauma, Religiosity, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research, Religion & Public Life Project: Religious Landscape Survey. Religious Landscape Survey. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Proietti JM, Barkham M. Scales for personality disorders developed from the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1996;10(4):355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Luscher KA, Smalley KJ, Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Williams WC. Screening for personality disorders in a nonclinical population. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1999;13(4):345–360. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1999.13.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola J, Hodgdon H, Liang L, Ford JD, Layne CM, Pynoos R, Kisiel C. Unseen wounds: The contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:S18–S28. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron JC, Scarpa A, Kim-Spoon J, Coe C. Adult sexual experiences as a mediator between child abuse and current secretory immunoglobulin A levels. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016;31:942–960. doi: 10.1177/0886260514556763. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260514556763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins B, Bentovim A. The sexual abuse of male children and adolescents: A review of current research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:197–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]