Abstract

Objective:

To see whether phloroglucinol-added tamsulosin therapy exhibits better efficacy than tamsulosin alone in medical expulsion of lower ureteral stone (LUS).

Methods:

Sixty four consecutive adult patients presented in a urological setting at Sialkot, Pakistan between January 2015 and December 2016 with solitary, unilateral 3-8mm sized lower ureteral stone (reported by noncontrast computed tomography of the kidney-ureter-bladder) were documented. Group either study or control was allotted, randomly. Same 0.4 mg tamsulosin, once daily was given to all the participants. However, additional 40 mg phloroglucinol, thrice daily was advised for study group (n = 32). The therapy terminated on confirmation of stone expulsion otherwise continued for 6 weeks. Patients were asked to use 50 mg diclophenac Na on colic episode.

Results:

Demographic characteristics revealed 81.2% (n = 52) male patients while age statistics as M = 42.3, SD = 5.93 (range 32-60) years. The study group showed higher stone expulsion rate (100%) and time to expulsion (M = 10.34 days) than control. The values were statistically significant (p = .02 and p = .0001; χ2 test in SPSS). Similarly, combination therapy had advantage on mono therapy for reporting statistically lesser numbers of colic episode (p = .03) and consumption of analgesic (p = .02). A marked difference in rate of adverse effects i.e. 68.8 vs. 90.6% was observed in study and control groups.

Conclusion:

Phloroglucinol-added therapy is a better choice for expulsion of LUS than tamsulosin alone with reference to stone expulsion rate and medication time.

Keywords: Combination therapy, Medical expulsive therapy, Phloroglucinol, Tamsulosin, Ureteral calculi

INTRODUCTION

Gradually increasing incidence rate of kidney stone is a significant concern of medical world. Genetics and/or life style e.g. stay in hot humid climate accelerate the urolithiasis – the kidney stone formation. Males are at higher risk of incidence than females; a probable impact of endocrinological differentiation. Similarly, likelihood of its occurrence maximizes at the age around 30 years. Sometimes, it is stuck up in ureter especially distal ureter; hence called as lower ureteral stone (LUS) and causes intense flank pain beside urinary obstruction. Stone removal is the only remedial step. However, unlucky sufferers especially children may face the same situation after few years.1 This poses extra financial burden in the family and pressure on public health sector.

A medical practitioner decides type of therapeutic modality for ureteral stone expulsion/removal on clinical manifestations and diagnostic findings. Medical expulsive therapy (MET) is opted for the sufferers agreed to waiting management.2 Here, patient is free to move for daily functioning without any hindrance like hospitalization. Higher stone expulsion rate, lower health risks, cost-effectiveness, and a chance to avail minimal invasive treatment (on failure) are some of its salient features. Similarly, taking diclophenac Na – the analgesic on colic episode makes the person tension-free.3 So, the MET successfully covers psycho-physiological dimensions of an undergoing beneficiary.

Smooth muscle makes wall of the ureter. Internally, it is lined with alpha-1 adrenergic receptors particularly in lower 1/3rd portion of the ureter also called distal ureter. The receptors detect the stone and stimulate peristalsis for its passage. Otherwise, blockade of receptors (by stone) leads to spasm in stone-surrounding muscle, local edema and inflammation. Colic pain develops when peristalsis attempts to push the stone through the inflamed region. An antagonist of the receptors reverses the mechanism4; hence facilitates the stone expulsion. Similarly, analgesic obstructs the transmission of pain stimulus to central nervous system. So, clinicians recommend therapy in the light of stone size as well as controlled symptoms.5 Tamsulosin is the choice of physicians for two reasons viz. high stone expulsion rate and short expulsion time. Similarly, the success rate of phloroglucinol as an anti-spasmodic drug6 is appreciable.

The option of combination therapy minimizes the chance of drug tolerance. Published literature has success stories of tamsulosin or phloroglucinol in combination therapy for expulsion of distal ureteral stone.7-9 However, there is no evidence of phloroglucinol-added tamsulosin therapy for the same purpose. This is why present work was planned to see whether addition of phloroglucinol with tamsulosin enhances the efficacy for LUS expulsion compared to sole tamsulosin. The findings will motivate scientific community to test-retest the modality before recommendation in countries like Pakistan10 where MET is the only readily available therapy for the LUS.

METHODS

The prospective experimental study was carried out in the Kidney Centre – a urological setting at Sialkot, Pakistan between January, 2015 and December, 2016 after getting clearance from the hospital ethics committee.

Sample size (n) was calculated vide a formula ‘z2pq/d2’ using p = 18% (derived from secondary data of the centre). Consecutive adult patients with a ureteral 3-8mm sized stone lodged below common iliac vessels as confirmed by computed tomography (noncontrast) were registered provided diclophenac injection relieved pain in 24 hour. However, sufferers with hydronephrosis, renal failure, diabetes, peptic ulcer, user of β-blockers, calcium antagonists, or nitrates (as treatment); pregnant or lactating mothers; who demanded urgent stone removal or refused to give written participation consent were excluded. Random group allotment was ensured to make two equal groups (n = 32) using computer-generated table. Furthermore, baseline information of each recruiter was documented before medication.

Patients in study group were given tamsulosin 0.4 mg once daily with phloroglucinol 40 mg twice daily. However, tamsulosin 0.4 mg once daily was advised for matched control. Drugs were continued until stone removal or for a maximum six weeks as suggested by Kumar and associates.8 Need-based use of 50 mg diclophenac Na tablet was recommended on colic pain. Furthermore, patients were educated to use purpose-built mesh net to notice stone expulsion. On reporting of stone expulsion, the patient was evaluated by noncontrast computed tomography of the KUB (kidney-ureter-bladder) along with physical examination, serum creatinine, and urine culture. Failure in stone expulsion (after 6 weeks) was dealt with extracorporeal shock lithotripsy.

Continuous variables were subjected to analysis for mean+/-standard deviations and compared by Mann Whitney U test for non normal distributions after normality test. Discrete variables were processed for rates/frequencies and evaluated through chi-squared test for association and risk estimates. Data were entered in worksheet of SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) one by one before analyses and interpretations. In both the tests, a p-value (<.05) was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

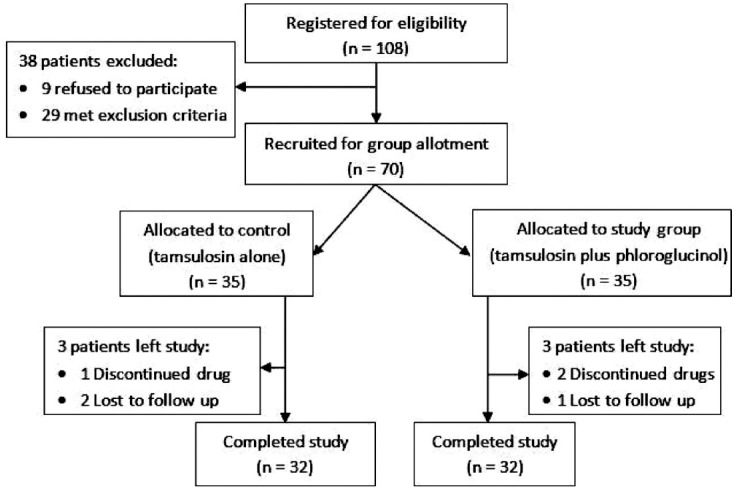

Sixty four (91.4% of total 70) patients completed the therapeutic session for expulsion of lower ureteral stone. The remaining were dropped out on drug(s) discontinuation or lose of follow up as shown in flow diagram of subject sampling (Fig.1).

Fig.1.

Flow diagram of subject sampling.

Table-Ia indicates statistics of baseline information of the participants. Statistically insignificant difference in mean age of participants of study group (M = 43.84, SD = 6.7; range 34-60) years and control was observed using Mann Whitney U test for non normal distributions (p = 0.29). Similarly, overall male population 52 (81.3%) dominated. In 62.5% (n = 36) patients, the single stone was diagnosed in left ureter by noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the kidney-ureter-bladder. Similarly, the size of stone in study group (M = 5.47mm in the biggest dimension i.e. axial plane) and control (M = 4.50 mm) showed significant difference (p = .0001).

Table-Ia.

Baseline information of the participants; n = 32 of each group.

| Variable | Value | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patients; count in each group | 32 | |

| Age; Mean±SD (range) years | ||

| Study group | 43.84±6.7 (34-60) | 0.29 |

| Control | 41.12±4.8 (32-49) | |

| Gender; count (%) | ||

| Male | 52 (81.3) | |

| Female | 12 (18.7) | |

| Stone laterization; count (%) | ||

| Center | 36 (62.5) | |

| Right | 28 (37.5) | |

| Stone size; Mean±SD (range) mm | ||

| Study group | 5.47±1.0 (3.4-6.8) | 0.0001 |

| Control | 4.50±0.6 (3.2-5.4) |

Predictors for stone expulsion were studied after noticing poor stone expulsion rate i.e. 81.2% (n = 26) in control group (Table-Ib). Comparatively lower values of stone expulsion rate were seen in patients: aged ≤40 years (77.3%, n = 17), males (75%, n = 18), having stone in left ureter (70%, n = 14), or stone size of >5mm (50%, n = 1). However, the rate showed insignificant association with any of the variables except stone laterization (p>05). The therapy was approximately 2-fold less effective in expulsion of stone from left ureter (OR=1.86; 95% CI: 1.30-2.65) than right ureters (p = 0.04).

Table-Ib.

Risk estimates in participants of control group (n = 32).

| Variable | Stone expulsion; % (n) | Odd ratio; 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |||

| ≤40 | 77.3 (17) | 2.65; 0.27-26.25 | 0.37 |

| >40 | 90 (9) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 75 (18) | 1.44; 1.12-1.87 | 0.15 |

| Female | 100 (8) | ||

| Stone laterization | |||

| Center | 70 (14) | 1.86; 1.30-2.65 | 0.04 |

| Right | 100 (12) | ||

| Stone size (in mm) | |||

| ≤5 | 83.3 (25) | 0.20; 0.01-3.76 | 0.35 |

| > 5 | 50 (1) |

Data presented in Table-II show cent percent stone expulsion (n = 32) against therapy using tamsulosin with phloroglucinol for stone expulsion. However, risk estimates revealed that a patient treated with mono therapy had lesser chances of stone expulsion (RR: 0.812; 95% CI: 0.688-0.960) compared to that of combination therapy (p = 0.02).

Table-II.

Therapy vs. stone expulsion rate; and risk estimates.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Stone expulsion; % (n) | |

| Combination therapy | 100 (32) |

| Mono therapy | 81.2 (26*) |

| Relative risk estimates | RR = 0.812; 95% CI: 0.688 – 0.960; p = .02 |

In18.8% (n = 6) subjects, the stone was removed by extracorporeal lithotripsy

Data in Table-III depicts comparative accounts of medication time in phloroglucinol-added and –free therapies. Combination therapy had advantage on mono therapy as it expelled the distal ureteral stone in significantly lower mean time, 10.34 (SD = 3.5; range 3-15) days after start of medication (p = .0001). The therapy also showed efficacy against both, small (≤5) and large-sized stones (>5 mm) by removing all such stones i.e. 6 (18.8%) and 26 (81.2%) within 7 and 15 days of treatment, respectively.

Table-III.

Medication days vs. type of medical expulsion therapy.

| Variable | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Medication time; Mean+/-SD (range) days | ||

| Combination therapy | 10.34 ±3.5 (3-15) | |

| Mono therapy | 17.69 ±2.8 (9-21) | (p = .0001) |

| Medication time; Range (n, %) days | ||

| Combination therapy (≤5 mm-sized stone) | 1-7 (6, 18.8) | |

| Mono therapy… | 8-14 (4, 12.5), 15-21 (21, 65.6) | |

| Combination therapy (>5 mm-sized stone) | 1-7 (1, 3.1), 8-14 (24, 75.0), 15-21 (1*, 3.1) | |

| Mono therapy | 15-21 (1**, 3.1) |

15thand

20thday of medication

Colic episode needed couples use of analgesic (50mg diclophenac Na). The patients of study group reported significantly lesser numbers of pain incidence (M = 0.19, SD =0.4) as shown in Table-IV (p =.03). So, a remarkable difference in mean consumption of analgesic (12.50 vs. 29.69 mg) was noticed between study and control groups to relieve pain (p = .02). Only one patient of study group had to visit emergency room without being hospitalized. However, one subject from control had to stay at hospital for certain complications.

Table-IV.

Colic episode/analgesic vs. type of therapy.

| Variable | Value | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Colic episode; Mean+/-SD (range) count | . | |

| Combination therapy | 0.19±0.4 (0-1) | 03 |

| Mono therapy | 0.52±0.6 (0-2) | |

| Analgesic; Mean+/-SD (range) mg | ||

| Combination therapy | 12.50±22.0 (0-50) | .02 |

| Mono therapy | 29.69±30.8 (0-100) | |

| Visit of emergency room; count | ||

| Combination therapy | 1 | |

| Mono therapy | 4 | |

| Hospitalization; count | ||

| Combination therapy | Nil | |

| Mono therapy | 1 |

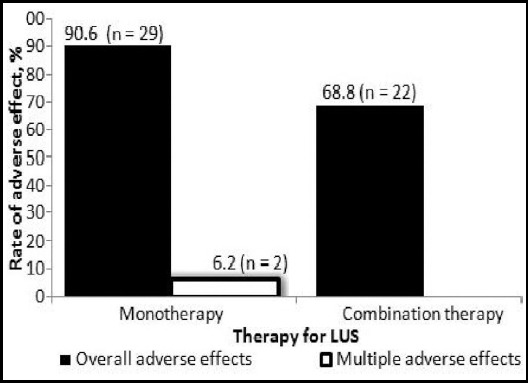

Incidence of adverse effects against both therapies is shownin Fig.2. In patients with phloroglucinol-added therapy, the rate 68.8% (n = 22) was comparatively lower. Moreover, asthenia was found as the most prevalent adverse effect of present investigation. Other effects included headache, orthostatic hypotension, palpitation, nausea/vomiting, and gastro intestinal disorders. Additionally, the phloroglucinol-added medication showed its advantage on having no multiple adverse signs.

Fig.2.

Rate of adverse effect against therapies for LUS (n = 32).

DISCUSSION

The LUS (lower ureteral stone)-mediated colic pain is associated with a sense of unknown fear and subsequently declination towards any activity. Radom group allotment rules out any risk of bias11 in subject sampling. Similarly, leaving the study (within the session) is the consequence of self-perceived poor prognosis,12 outcome of adverse effects or any other drive e.g. economic constrains.

Mean age of participants in present work (early 40’s) looks quite different from that of late 40’s, mid 30’s, or 20’s.8,10,12 The deviation may have differences in life style including dietary habits, and climate. Females are usually less prone to the LUS.13,14 Our results i.e. 12 out of 64 (i.e. 18.8%) substantiate this general concept. The mark difference can be interpreted with respect to sex-linked endocrinology. Comparatively higher rate of stones in left ureter is just a chance otherwise 1:1 ratio is expected.15 Just like in a published work16, the mean value of stone (about 5 mm) indicates the commonness of this size in the patients of LUS.

Output of insignificant association between stone expulsion rate and baseline information of the control group (tamsulosin alone) reveals equal impacts of the MET on both the categories of each characteristic. Almost similar findings has been documented by authors15, working on rate of ureteroscopy for the LUS. Failure to expel some stones from left ureter is surprising and can be traced back to some risk factors such as uneven surface of the stone and/or irregularity in medication.

The 100% stone expulsion rate against phloroglucinol-added tamsulosin therapy of present investigation is higher than previously reported for sole phloroglucinol (64%),6,22 tamsulosin,21-24 tadalafil-added tamsulosin,8,17 or tolterodine-added tamsulosin.20 The better efficacy of tamsulosin plus phloroglucinol medication is a good example of synchronization impact of the drugs towards the desired purpose i.e. stone expulsion. Luckily, combination therapy discourages drug tolerance in the patients.

The MET is the choice of people agreed to waiting management for the LUS. Our combination therapy expelled the stones in lesser mean time (in days) than already reported 8,17 using other set of medicines e.g. tadalafil-added tamsulosin. Almost equal affectivity of our combination modality for both, small and large-sized stones advocate its future prospective in medicinal world.

Decline in frequency of the colic episodes in combination therapy marks the anti-spasmodic role of added phloroglucinol.6 Decline in number of patients with the colic episode(s) in the combination (n=6; 18.8% compared to monotherapy n=14; 43.8%) is steeper than parecoxib (n =17; 14.3%) and parecoxib plus phloroglucinol (n=7; 6.1%) of a published data.18 It appears that phloroglucinol becomes more effective when it is in partnership with tamsulosin. Decrease in demand of analgesic in combination therapy makes the therapy cost effective.

Comprehensive reporting of the adverse effects is required along with medicine to balance its overemphasized benefits.19 The combination therapy of present work shows advantage over matched tamsulosin alone in term of rate of the effects.

CONCLUSION

Combination therapy has advantage over monotherapy in term of stone expulsion rate, medication time, colic episodes, use of analgesic drugs, and adverse side effects. The findings will guide the researchers to retest the applicability of the modality at higher levels before general application.

Authors’ Contribution

MNS conceived, designed, collected data and wrote manuscript.

MH applied statistical analyses; edited, reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Grant Support & Financial Disclosures None.

Conflict of interest None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tasian GE, Kabarriti AE, Kalmus A, Furth SL. Kidney stone recurrence among children and adolescents. J Urol. 2017;197(1):246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.07.090. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picozzi CS, Marenghi C, Casellato S, Ricci C, Gaeta M, Carmignani L. Management of ureteral calculi and medical expulsive therapy in emergency departments. JEmerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(1):70–76. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.76840. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.76840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed AA, Al-sayed AS. Tamsulosin versus alfuzosin in the treatment of patients with distal ureteral stones:prospective, randomized, comparative study. Korean J Urol. 2010;51(3):193–197. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.3.193. doi:10.4111/kju.2010.51.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varshney A. Current management of ureteric stones. JIMSA. 2011;24(3):115–116. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang RC, Smith-Bindman R, Whitaker E, Neilson J, Allen IE, Stoller ML, et al. Effect of tamsulosin on stone passage for ureteral stones:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(3):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.06.044. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Medical-expulsive therapy for distal ureterolithiasis:randomized prospective study on role of corticosteroids used in combination with tamsulosin-simplified treatment regimen and health-related quality of life. Urol. 2005;66(4):712–715. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.055. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alizadeh M, Magsudi M. The effect of tamsulosin in the medical treatment of distal ureteral stones. GlobalJ Health Sci. 2014;6(7):44–48. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n7p44. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v6n7p44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar S, Jayant K, Agrawal S, Singh SK. Comparative efficacy of tamsulosin versus tamsulosin with tadalafil in combination with prednisolone for the medical expulsive therapy of lower ureteric stones:a randomized trial. Korean J Urol. 2014;55(3):196–200. doi: 10.4111/kju.2014.55.3.196. doi:10.4111/kju.2014.55.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boubaker H, Boukef R, Claessens Y-E, Bouida W, Grissa MH, Beltaief K, et al. Phloroglucinol as an adjuvant analgesic to treat renal colic. American J. Emerg Med. 2010;28(6):720–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.04.030. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad H, Azim W, Akmal M, Murtaza B, Mahmood A, Nadim A, et al. Medical expulsive treatment of distal ureteral stone using tamsulosin. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2015;27(1):48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickard R, Starr K, MacLennan G, Lam T, Thomas R, Burr J, et al. Medical expulsive therapy in adults with ureteric colic:a multicentre, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):341–349. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60933-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60933.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legge SE, Hamshere M, Hayes RD, Downs J, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, et al. Reasons for discontinuing clozapine:A cohort study of patients commencing treatment. Schizophrenia Res. 2016;174(1):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.002. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramello A, Vitale C, Marangella M. Epidemiology of nephrolithiasis. JNephrol. 2000;13(Suppl. 3):S45–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirzada AJ, Anwar A, Atif J, Memon I, Ariz M. Role of alpha-1 blocker in expulsion of stone fragments after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for renal stones. JAyub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2011;23(2):125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hameed D, Safwat A, Osman M, Gadelmoula M, Kurkar A, Elgammal M. Outcome of ureteral distensibility on the success of ureteroscopy:A prospective hospital-based descriptive study. AfricanJ Urol. 2017;23(1):33–37. doi:10.1016/j.afju. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollingsworth JM, Canales BK, Rogers MA, Sukumar S, Yan P, Kuntz GM, et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones:systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;355:i6112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6112. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayant K, Agrawal R, Agrawal S. Tamsulosin versus tamsulosin plus tadalafil as medical expulsive therapy for lower ureteric stones:a randomized controlled trial. IntJ Urol. 2014;21(10):1012–1015. doi: 10.1111/iju.12496. doi:10.1111/iju.12496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu W, Yao J, Li Q, Wu X, Zhou Z, Li W. Efficacy and safety of parecoxib/phloroglucinol combination therapy versus parecoxib monotherapy for acute renal colic:A randomized, double-Blind clinical trial. CellBiochem Biophysics. 2014;69(1):157–161. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, O'Neil RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials:an expansion of the consort statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;141(10):781–788. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erturhan S, Erbagci A, Yagci F, Celik M, Solakhan M, Sarica K. Comparative evaluation of efficacy of use of tamsulosin and/or tolterodine for medical treatment of distal ureteral stones. Urol. 2007;69(4):633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.009. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griwan MS, Singh SK, Paul H, Pawar DS, Verma M. The efficacy of tamsulosin in lower ureteral calculi. UrolAnn. 2010;2(2):63–66. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.65110. doi:10.4103/0974-7796.65110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. JUrol. 2005;174(1):167–172. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161600.54732.86. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000161600.54732.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furyk JS, Chu K, Banks C, Greenslade J, Keijzers G, Thom O, et al. Distal ureteric stones and tamsulosin:a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(1):86–95.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClinton S, Starr K, Thomas R, McLennan G, McPherson G, McDonald A, et al. Use of drug therapy in the management of symptomatic ureteric stones in hospitalized adults (SUSPEND), a multicentre, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of a calcium-channel blocker (nifedipine) and aα-blocker (tamsulosin):study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:238. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-238. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]