Abstract

Microsomal glutathione transferase 1 (MGST1) has a unique ability to be activated, up to 30-fold, by modification with sulfhydryl reagents. MGST1 exhibits one-third-of-the-sites-reactivity towards glutathione and hence heterogeneous binding to different active sites in the homo-trimer. Limited turnover stopped flow kinetic measurements of the activated enzyme allowed us to more accurately determine KD for the “third” low affinity GSH-binding site (1.4 ± 0.3 mM). The rate of thiolate formation, k2 (0.77 ± 0.06 s−1), relevant to turnover, could also be determined. By deriving the steady-state rate equation for a random sequential mechanism for MGST1 we can predict KM, kcat and kcat/KM values from these and previously determined pre steady-state rate constants (all determined at 5°C). To assess whether the pre steady-state behavior can account for the steady-state kinetic behavior we have determined experimental values for kinetic parameters at 5°C. For reactive substrates and activated enzyme, data for the microscopic steps account for the global mechanism of MGST1. For unactivated enzyme and more reactive electrophilic substrates, pre steady-state and steady-state data can be reconciled only if a more active subpopulation of MGST1 is assumed. We suggest that unactivated MGST1 can be partially activated in its unmodified form. The existence of an activated subpopulation (approximately 10%) could be demonstrated in limited turnover experiments. We therefore suggest that MSGT1 displays a pre-existing dynamic equilibrium between high and low activity forms.

Keywords: MGST1, glutathione transferase, kinetic mechanism, limited turnover

TOC Graphic

INTRODUCTION

Glutathione transferases (GST) catalyze the conjugation of glutathione to a variety of molecules bearing electrophilic centers and are by this mechanism involved in the detoxification of numerous carcinogenic, mutagenic, toxic and pharmacologically active compounds1. The electrophilic substrates are usually converted to less reactive, water-soluble conjugates that can readily be excreted from the body. GSTs have also been suggested to protect tumors from chemotherapy2. Further, expression of GSTs in multiple species is up-regulated in response to3, and acts in the cells as a protection mechanism, against oxidative stress4. The great variety and substrate promiscuity of GSTs has also inspired basic research to study fundamental issues of enzyme evolution and function5–8,9.

Three membrane-bound GSTs (MGST1, MGST2, and MGST3) have been grouped into the Membrane-Associated Proteins in Eicosanoid and Glutathione Metabolism (MAPEG) superfamily together with 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP), leukotriene C4 synthase (LTC4S), and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (MPGES1). The MAPEG superfamily plays an important role in cellular protection and eicosanoid signaling10. Members of this family use glutathione to catalyze transformations of lipophilic substrates harvested from the lipid bilayer11–14,15, with the exception of FLAP that is thought to present arachidonic acid to 5-lipoxygenase16.

The first member of this group to be characterized was MGST1, a 17.3 kDa/subunit homo-trimeric enzyme. MGST1 is an abundant enzyme constituting 3% of the endoplasmic reticulum protein in rat liver and 5% of the outer mitochondrial membrane17. Similar to many cytosolic GSTs it is involved in the cellular defense against xenobiotics and intermediates produced during oxidative stress18, 19 with broad substrate specificity20. Pre steady-state kinetic steps have been characterized for MGST121–23, MGST224,25, and LTC4S26 whereas determination of global mechanisms has only been accomplished for soluble GSTs27–30.

A unique feature of MGST1 is that this enzyme can be activated, up to 30-fold, by sulfhydryl reagents and proteolysis19, 31, 32. Studies involving pre steady-state kinetic analysis using stopped flow spectrophotometric methods and a series of electrophilic substrates defined GSH thiolate formation as the step that, upon modifying the stress sensor cysteine-49, is increased leading to activation21, 22, 33. The chemical step is directly related to the reactivity of the electrophilic substrate and not influenced by “activation”. In principle, the microscopic rate and equilibrium constants obtained for MGST1 should also fit the steady-state behavior of the enzyme. However for practical reasons (the activated MGST1 is unstable without GSH at 30°C) the pre steady-state kinetic characterization was performed at 5°C, whereas earlier published steady-state analysis of the same protein was carried out at 30°C32, 34. Thus, direct comparison between pre steady-state and steady-state data has not been possible and a global mechanism could not be tested. To fill this gap we have performed a steady-state analysis of MGST1 at 5°C in order to determine whether the microscopic rate constants obtained for MGST1 accurately predict the steady-state kinetic parameters. The KM, kcat and kcat/KM values were also calculated from the steady-state rate equation for a random sequential mechanism32. The comparison between calculated and experimentally obtained kinetic parameters yields a reasonable fit for more reactive substrates and activated enzyme. However, kinetic parameters for less reactive electrophilic substrates deviate significantly as do kinetic parameters for the unactivated enzyme and the more reactive substrates. These discrepancies have led to a deeper understanding of the enzyme regarding behavior at low temperature and also indicate the presence of a small (perhaps inherent) population in the activated state. Our studies thus point to a very interesting property of the “unactivated” nonmodified enzyme that appears to be partly activated. We therefore propose that chemical or environmental factors that lead to the activation of MGST1 can be thought of as shifting the proportions/equilibrium between two pre-existing enzyme populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) was obtained from Merck Co. (Darmstadt, Germany). 4-Chloro- 3-nitroacetophenone (CNAP) was from Aldrich-Chemie (Steinheim, Germany). 4-Chloro-3-nitrobenzamide (CNBAM) was from Alfred Bader Library of Rare Chemicals, Division of Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). 2,5-Dichloronitrobenzene (2,5-DCNB) was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Glutathione (GSH) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals were of reagent grade and obtained from common commercial sources.

Enzyme Preparation

MGST1 was purified from male Sprague–Dawley rat livers as described previously20, with the exception that 0.2% Triton X-100 was used during the final purification. Activation of MGST1 was accomplished by adding NEM (5 mM final concentration) to the enzyme, on ice, in purification buffer. The reaction was stopped by adding equimolar GSH. The activated enzyme was kept on ice at all times and was prepared prior to the experiment on the same day.

Stopped-Flow Limited Turnover Experiments

The entire enzymatic turnover process was measured on an Applied Photophysics stopped-flow instrument as described previously21. Between 50 and 100 µL from each of two syringes was rapidly mixed in a 10 mm path length cell, and the signal was recorded. When applying 20 mM GSH concentration, a 2-mm cell was employed to allow for the high-background absorbance of GSH. All experiments were performed at 5 °C in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 20% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X-100 and 0.1 mM EDTA (Buffer X). All concentrations given below are the resulting final concentrations in the observation cell. The enzyme concentration is expressed as the concentration of subunits. Absorbance was measured at 239 nm and the signal was followed for the thiolate anion (ε239 = 5000 M−1cm−1) and CDNB (ε239 = 2700 M−1cm−1). Of note, CDNB absorbance decreases upon product formation at 239 nm in contrast to the gain measured at 340 nm (ε340 = 9600 M−1 cm−1) in the standard activity assay.

Steady-State Kinetics

Steady-state kinetic parameters for MGST1 were determined on a Cary 60 UCV-Vis spectrophotometer using four different electrophilic substrates: CDNB, CNAP, CNBAM, 2,5-DCNB. The activity of the enzyme was determined at saturating GSH concentration in a 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5 mM GSH. CDNB was varied between 4 and 250 µM. CNAP was varied between 5 and 500 µM. CNBAM and 2,5-DCNB were varied between 0.016 and 1 mM. The activity of the enzyme was also determined at saturating electrophilic substrate concentrations in a 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and either 0.5 mM CDNB, 1 mM CNAP, 1 mM CNBAM or 1 mM 2,5-DCNB. GSH was varied between 0.04 and 20 mM. All experiments were performed at 5 °C. At least triplicate determinations were performed at each concentration. The rate of product formation was monitored by measuring the change in absorbance at different wavelengths as described by Keen et al.35. The extinction coefficient for the product using 2,5-DCNB was corrected from that published35 and is 2200 M−1cm−1 (determined by running reactions to completion with limiting substrate). Data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation yielding the kinetic parameters kcat and KM.

Data simulation and analysis

Limited turnover data was analyzed using the KinTek Explorer software program36, 37. Kinetic parameters were derived by nonlinear regression using the program package GraphPad Prism 5. Molecular graphics were generated with PYMOL (www.pymol.org).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

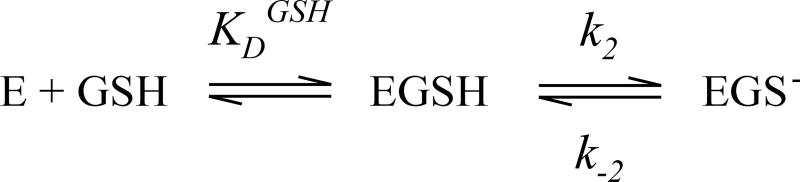

We have studied the reaction mechanism of MGST1 using pre steady-state and steady-state kinetics. A simplified mechanism showing rate and equilibrium constants is depicted in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Further, we have derived the steady-state rate equation and used it to calculate predicted KM, kcat and kcat/KM values, which we in turn have compared to the experimentally derived constants for all substrate combinations. Studying MGST1 we take advantage of being able to control the rate of the chemical catalytic step by using a series of substrates with defined reactivity34 (Figure 1). We can also modulate the rate of the GSH thiolate anion formation step by pre-treating enzyme with a sulfhydryl reagent leading to activation31.

Figure 1.

Structures of the electrophilic substrates used in this study and their specific reactivity described by Hammett substituent constants for the para position (σ−): 2,5-dichloronitrobenzene (2,5-DCNB, σ− = 0.23), 4-chloro-3-nitro-benzamide (CNBAM, σ− = 0.63), 4-chloro-3-nitroacetophenone (CNAP, σ− = 0.87), 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB, σ− = 1.3).

Microscopic rate and equilibrium constants for MGST1 catalysis

In Table 1 we have collected the microscopic rate and equilibrium constants derived from pre steady-state experiments for a series of electrophilic substrates for both unactivated and activated MGST1. Both GSH and the electrophilic substrate display rapid equilibrium binding and subsequent thiolate formation in case of GSH or chemical conjugation to enzyme bound GSH thiolate in the case of the electrophilic substrate.

Table 1.

Pre steady-state kinetic constants for MGST1 from stopped flow experiments performed at 5°C

| Activated MGST1 | Unactivated MGST1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Substrate |

KD (mM) |

k2’ (s−1) | k−2’ (s−1) | k3 (s−1) |

KD (mM) |

k2 (s−1) | k−2 (s−1) | k3 (s−1) |

|

|

|

|||||||

| GSH | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.016 ± 0.0005b | 2.5 ± 0.5c | 0.023 ± 0.001c | 0.0006 ± 0.00003a | ||

| 2,5-DCNB | 0.08 ± 0.03d | 0.14 ± 0.01d | 0.08 ± 0.03a | 0.14 ± 0.01a | ||||

| CNBAM | 0.6 ± 0.1d | 1 ± 0.1d | 0.6 ± 0.1a | 1 ± 0.1a | ||||

| CNAP | 0.4 ± 0.1b | 4.1 ± 0.7b | 1.1 ± 0.6a | 15 ± 6a | ||||

| CDNB | 0.53 ± 0.08e | 510 ± 40e | 0.53 ± 0.08a | 510 ± 40a | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||

It is important to note that GSH binding and thiolate anion formation originally recorded by rapid mixing of MGST1 and GSH21 are not used here. These constants do not reflect enzyme behavior during turnover since the enzyme displays third of the site reactivity23 and will thus not exist in non-GSH liganded states. Hence we used a limited turnover approach, as previously used for the unactivated enzyme23, to determine the thiolate formation rate and equilibrium constant for GSH as it binds to activated MGST1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

GSH-binding and thiolate formation to activated MGST1 after limited turnover. Limited turnover experiment where GSH-bound MGST1 is rapidly mixed with CDNB at a ratio of approximately 1.5/trimer. Thiolate anion re-formation was recorded after the initial burst (mixing the enzyme with 8 µM CDNB) as an increase in absorbance at 239 nm with 0.25–20 mM GSH. The dependence of kobs for GSH thiolate formation on GSH concentration was fitted to Equation 1 in GraphPad Prism 5. Measurement values are given ± standard error of the mean. Enzyme concentration used was 5.8 µM trimer as measured by an active site titration (not shown).

Determination of KD and k2 was performed by fitting to equation (1) with the software GraphPad Prism 5.

| (1) |

This approach is more relevant for physiological and steady state behavior as the enzyme will be fully loaded with GSH in vivo. After a catalytic cycle two of the three sites will retain their GSH molecules, whereafter relevant GSH binding and thiolate formation occurs to this enzyme form. The chemical reaction rate constants for the electrophilic substrates were obtained from analysis of bursts of product formation21, 22. However, for less reactive electrophilic substrates, thiolate anion formation is no longer the rate limiting step. Therefore, for 2,5-DCNB and CNBAM data from unactivated enzyme was used since no burst occurs upon rapid mixing with activated MGST1. For CDNB no saturation could be obtained with activated enzyme and data from unactivated enzyme was used. Dissociation constants for the electrophiles are close to solubility limits and should be regarded with some caution. To summarize, we have experimentally determined or estimated rate and equilibrium constants (Table 1) that, if our understanding of the kinetic mechanism is complete, should predict the steady-state behavior of MGST1.

Steady-State rate equation

In order to evaluate the global mechanism of MGST1 we have derived a steady-state rate equation for a random sequential kinetic mechanism for which there is experimental support32 (Scheme 2, Equation 2).

| (2) |

Scheme 2.

In this equation, C represents the electrophilic substrate, k2 is the rate constant for thiolate anion formation whereas k−2 is the rate constant for the reverse process, k3 is the rate constant for the chemical step that is essentially irreversible, KC and KG are the dissociation constants for the electrophilic substrate and GSH respectively. The representation of the enzyme’s mechanism corresponds to what is occurring in one of its active sites. This simplification is possible because of the rapid equilibrium behavior and as there are no signs of cooperativity in the steady-state data. KD for the electrophilic substrates was determined in the presence of GSH and KD for GSH was determined in the absence of electrophilic substrate. As a simplification we assume the same dissociation constants for the electrophilic substrate and GSH, independently of which molecule binds first to the enzyme.

The steady-state rate equation is used for both unactivated and activated enzyme. At saturating GSH concentration and varying concentration of the electrophiles the expression is reduced to equation 3 and the values for KM and kcat are calculated according to equations 3.1 and 3.2 respectively.

| (3) |

| (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

At saturating concentrations of electrophiles and varying GSH concentration the expression is reduced to equation 4 and the values for KM and kcat can be calculated according to equations 4.1 and 4.2 respectively.

| (4) |

| (4.1) |

| (4.2) |

Rate and dissociation constants are given in Table 1 and the resulting theoretical catalytic constants as calculated from the corresponding equations are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Calculated steady-state constants for MGST1 based on data from Table 1 and the derived steady-state rate equation

| Saturating GSH, varying electrophile | ||||||

| Activated MGST1 | Unactivated MGST1 | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Substrate |

KM (µM) |

kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

|

| ||||||

| 2,5-DCNB | 68 | 0.12 | 1 800 | 12 | 0.02 | 1 700 |

| CNBAM | 260 | 0.43 | 1 700 | 14 | 0.022 | 1 600 |

| CNAP | 64 | 0.65 | 10 000 | 1.7 | 0.023 | 14 000 |

| CDNB | 0.77 | 0.77 | 1 000 000 | 0.02 | 0.023 | 1 200 000 |

|

| ||||||

| Varying GSH, saturating electrophile | ||||||

| Activated MGST1 | Unactivated MGST1 | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Substrate |

KM (µM) |

kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

|

| ||||||

| 2,5-DCNB | 240 | 0.12 | 500 | 2 100 | 0.02 | 9.5 |

| CNBAM | 800 | 0.43 | 540 | 2 400 | 0.022 | 9.2 |

| CNAP | 1 200 | 0.65 | 540 | 2 500 | 0.023 | 9.2 |

| CDNB | 1 400 | 0.77 | 550 | 2 500 | 0.023 | 9.2 |

Steady-State Kinetic measurements

The experimentally derived steady-state constants obtained from rate measurements at 5 °C are shown in Table 3. If the predicted global mechanism for MGST1 is correct the theoretical and experimental catalytic constants should be comparable. We can see that the calculated and theoretical kinetic constants do differ considerably for certain substrates.

Table 3.

Experimental steady-state constants for MGST1 from analysis performed at 5°C

| Saturating GSH, varying electrophileActivated MGST1 | Unactivated MGST1 | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Substrate | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

|

| ||||||

| 2,5-DCNB | 240 ± 4 | 0.0059 ± 0.004 | 25 ± 5 | 56 ± 8 | 0.0028 ± 0.0001 | 50 ± 9 |

| CNBAM | 770 ± 70 | 0.088 ± 0.006 | 110 ± 20 | 34 ± 7 | 0.0099 ± 0.0005 | 290 ± 70 |

| CNAP | 38 ± 6 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 8200 ± 1000 | 77 ± 10 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 210 ± 30 |

| CDNB | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 180 000 ± 40 000 | 11 ± 2 | 0.14 ± 0.007 | 13 000 ± 3 000 |

|

| ||||||

| Varying GSH, saturating electrophileActivated MGST1 | Unactivated MGST1 | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Substrate | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

|

| ||||||

| 2,5-DCNB | 170 ± 30 | 0.0039± 0.0002 | 23 ± 5 | 110 ± 50 | 0.0021 ± 0.0002 | 19 ± 1 |

| CNBAM | 400 ± 30 | 0.048 ± 0.002 | 120 ± 10 | 390 ± 220 | 0.0060 ± 0.0001 | 15 ± 9 |

| CNAP | 450 ± 60 | 0.11 ± 0.003 | 240 ± 30 | 740 ± 80 | 0.012 ± 0.0004 | 16 ± 2 |

| CDNB | 960 ± 70 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 510 ± 60 | 2500 ± 160 | 0.17 ± 0.003 | 68 ± 6 |

Measured and predicted KM values for electrophilic electrophilic substrates

KM values for the electrophilic electrophilic substrates obtained for the activated enzyme differ between predicted and measured with the former being on average 3–5-fold lower. As the estimated KD for the electrophile does have considerable impact on the predicted KM (equation 3.1) this could be explained by overestimation of the affinity between the electrophilic substrate and the enzyme. The consistent ratio regardless of electrophilic substrate reactivity favors this interpretation. The same ratio is observed for unreactive substrates and the unactivated enzyme. However here this relationship breaks down for more electrophilic substrates where the ratio is 30–550. A contributing factor to these large discrepancies could be difficulties determining very low KM values in our activity assay. Ratios between all predicted and measured catalytic constants are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Ratios of the calculated vs experimental catalytic constants for (●) KM, (□) kcat and (▲) kcat/KM. (A) Activated MGST1, saturating GSH and varying electrophile concentrations. (B) Unactivated MGST1, saturating GSH and varying electrophile concentrations. (C) Activated MGST1, saturating electrophile and varying GSH concentrations. (D) Unactivated MGST1, saturating electrophile and varying GSH concentrations.

Measured and predicted KM values for GSH

The KM values for GSH are reasonably well predicted by equation 4.1 for the activated enzyme for all substrates except CNAP. Also for unactivated enzyme KM for GSH is well predicted when reactive electrophilic substrates are used. However for unreactive electrophilic substrates the relationship breaks down. This can be explained by the enzyme displaying a low activity resting state as is evident in kcat values and seems to be a property peculiar to measuring enzyme activity at the low temperature employed. This interpretation, further discussed below, is consistent with equation 4.1 where a lower k2 leads to a reduction of the apparent KM.

Measured and predicted kcat values

Predicted kcat values in Table 2 are the same regardless of which substrate is varied, as equations 3.2 and 4.2 were derived putting the non-varied substrate as infinite. Since we use reasonably saturating substrate concentration for the non-varied substrate this simplification only alters the calculated parameters to a small extent. As discussed above the kcat values for the least reactive substrates (2,5-DCNB and CNBAM) are not well predicted being 10–30 fold lower for the activated enzyme and 8-fold lower for 2,5-DCNB with the unactivated enzyme. For the two most reactive substrates, CDNB and CNAP, we find that the activated enzyme kcat is well predicted (Figure 3A and 3C). A catalytic cycle thus appears to mediate conversion of the enzyme to a high activity state that persists sufficiently for thiolate formation to be captured by reactive electrophilic substrates (what we suggest to be a memory effect). Similar effects have been reported for rGST T2-2 by Jemth and Mannervik29, where they propose a resting equilibrium state for the enzyme as well as several catalytically active conformations. On the contrary the kcat for the unactivated enzyme is not well predicted for these reactive substrates (with measured kcat up to 9-fold higher) (Figure 3B and 3D). The slowest microscopic rate constant for the unactivated enzyme is that of thiolate anion formation (k2 is 0.023 s−1) whereas kcat values as high as 0.17 s−1 were measured. As kcat cannot exceed the slowest microscopic rate constant on the reaction path we need to seek an explanation for this behavior. Results from limited turnover experiments where the rate of turnover can be directly compared to thiolate anion formation in the same experiment gave additional insight into the properties of the unactivated MGST1 that accounts for this apparent discrepancy.

Chemical catalysis and thiolate formation in limited turnover experiments with unactivated MGST1

The pre steady-state kinetic properties of MGST121–23 allow the performance of single/limited turnover experiments. Here, the enzyme, equilibrated with various concentrations of GSH, is rapidly mixed with stoichiometric (1/trimer) or higher concentrations of CDNB (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative image of the limited turnover process. The second order rate constant k4 will be used below for fitting the chemical reaction between EGS− and CDNB and was derived as the initial slope of the fit of CDNB bursts in references21, 22 circumventing any uncertainty in the binding affinity of CDNB.

Upon mixing, a rapid burst of product formation and release takes place that we describe as a bimolecular reaction with a corresponding rate constant, k4, to avoid any uncertainty in electrophile KD (Scheme 3). Then follows a “steady-state” turnover reaction where the enzyme bound thiolate anion is formed and reacts with excess CDNB resulting in depletion of the remaining substrate (Scheme 4).

Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

GSH rebinding to the empty site and slow thiolate anion formation finalizes the process (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

The absorbance trace results from loss of enzyme stabilized GSH thiolate and CDNB consumption in the burst phase, and consumption of CDNB during turnover and reformation of GSH thiolate in the rebound phase. Both the GSH thiolate and CDNB absorb more strongly than GSH and the CDNB-GSH conjugate (P) at 239 nm.

The chemical step is rapid with CDNB, as evident in the short burst phase. It follows that turnover and thiolate rebound phases are limited by the rate of GSH thiolate stabilization on the enzyme. Hence one would predict that the rate of these processes should be similar. This is clearly not the case with observed turnover being much more rapid than that predicted from k2 (seven times faster, Figure 5A). It thus becomes evident that k2, which was derived from the concentration behavior of the rebound phase23, cannot accurately predict turnover, and hence kcat for the unactivated MGST1 as observed (Table 2, 3 and Figure 3). This discrepancy is illustrated in the KinTek Explorer representation of the data and the predicted behavior in Figure 5A using rate and equilibrium constants from Table 1. There are several possible processes contributing to the marked difference between enzyme activity during turnover and thiolate anion formation after turnover. The slower rebound phase could result from a concomitant reversal to the low activity form observed when using very unreactive substrates. However this proposition is less likely since rates as low as 0.0021 s−1 (kcat for 2,5-DCNB in Table 3) were not observed. Instead, we propose that the unactivated enzyme first exits the resting state after the burst. After this a small proportion of the enzyme is in the activated form and contributes strongly to enhanced turnover but does only have a marginal contribution in the rebound phase as this represents the thiolate anion formation of the whole enzyme population. A good fit to the data assuming this scenario is obtained if approximately 10% of the enzyme is activated with a k2 of 0.77 (Figure 5B). In effect, “unactivated” MGST1 might exist as an equilibrium mixture between interconverting enzyme forms. Certainly, activation can be reversible as demonstrated earlier38.

Figure 5.

(A) Unactivated MGST1 limited turnover. Simulation based on assumption that the entire enzyme population is in its unactivated form. k2 is set to that optimized by the KinTec Explorer program in Figure 5B. (B) Unactivated MGST1 limited turnover. Simulation based on assumption that a fraction of the enzyme population is in an activated form (10 %). k2 for the unactivated and activated enzyme populations are fit by KinTek Explorer to 0.0055 s−1 and 0.77 s−1 respectively.

Treatment with sulfhydryl reagent (or other activators reviewed in Shimoji et al39) would then shift the equilibrium in favor of the activated enzyme. Recently we observed that the product formed from CDNB and GSH can also activate the enzyme (not shown), as has been observed for other ligands40. This indicates another process that could contribute to enhanced turnover. We are currently attempting to set up single molecule experiments to directly observe the enzyme during catalysis to characterize possible dynamic resting states and memory effects.

Chemical catalysis and thiolate formation in limited turnover experiments with activated MGST1

Fitting the GSH concentration dependence of kobs for the thiolate anion formation rebound yielded lower KD and k2 values for GSH in activated MGST1 compared to earlier data from empty enzyme22 (Table 1, Figure 2, Equation 1). The new data, obtained for the enzyme in limited turnover experiments, clearly yield rate and equilibrium constants for GSH interaction, which better fit the overall behavior of the enzyme (Table 2 and 3).

In principle, when the enzyme is homogeneously and fully activated by sulfhydryl modification, a limited turnover experiment should give the same rate for turnover as GSH thiolate formation rebound. As expected, the observed and predicted turnover rates for activated enzyme are much closer than those for the unactivated enzyme (Figure 6). Nevertheless, the values do not agree fully. A slow transition to a low activity state during the rebound could explain the discrepancy. Such a resting state is accessible also to the activated enzyme as evidenced by lower kcat values than predicted with the least reactive electrophilic substrates (compare Table 2 and 3). Another explanation might be a memory effect from product activation during turnover also for the activated enzyme as alluded to above.

Figure 6.

Activated MGST1 limited turnover. Simulation based on assumption that the entire enzyme population is in its activated form. k2 for the activated enzyme is fit by KinTek Explorer to 0.41 s−1.

GSH binding to the empty enzyme vs binding after a single turnover

GSH binding to MGST1 involves capturing GSH from the cytosol and burying it deep enough in the enzyme to expose the sulfur some distance into the lipophilic membrane. This process must by necessity involve structural transitions of the enzyme and is manifested as a slow step in MGST1 catalysis. The rate and equilibrium constants for GSH binding and thiolate anion formation also differ considerably when GSH binds to the empty enzyme21 or binds to the enzyme after a single turnover23. This is because the enzyme displays third of the sites reactivity and rebinding after a catalytic cycle involves binding of one GSH molecule to enzyme trimers already containing two GSH molecules. It is thus important to determine which process is representative for the enzyme catalysis. Thiolate anion formation in the enzyme is limited by slow conformational transitions and the rate constants for this process increase significantly in the empty enzyme compared to GSH containing enzyme: 10 vs. 0.42 s−1 for activated and 0.77 vs. 0.023 s−1 for unactivated MGST121–23. The KD for rapid equilibrium binding of GSH before deprotonation is higher in empty enzyme: 10 mM in activated and 47 mM in unactivated MGST1 compared to 1.4 mM and 2.5 mM in GSH containing enzyme21–23. Clearly, for the empty enzyme, these rate and equilibrium constants for GSH binding and thiolate anion formation are not compatible with the steady-state data obtained as they predict much higher KM and kcat values (not shown).

What then can be the physical explanation for the differences observed? As the enzyme is less stable without GSH, and hence probably more dynamic, this could explain a shift to a lower affinity population of enzyme. Thiolate anion formation involving structural transitions could be augmented in the non-GSH prebound more dynamic enzyme explaining rapid kinetics. Enzyme that has undergone one turnover at saturating GSH on the other hand appears to be in a conformational state with higher affinity for (the third) GSH but, being less conformationally flexible (stabilized by the other two GSH molecules), displays much slower thiolate anion formation kinetics (12–40 fold less for activated and unactivated enzyme respectively).

Hammett analysis

We have conducted a Hammett analysis on our steady-state kinetic parameters obtained at 5°C (Figure 7). As we have discussed above, there are several different phenomena that affect kcat and kcat/KM for MGST1, apart from the electrophile reactivity. Nevertheless it appears that kinetic parameters are linearly dependent on reactivity. The slopes of the plots for log kcat/KM electrophile (ϱ = 2.2–3.9) approach the slope for the non-enzymatic chemical reaction (not shown). The slopes of the plots for log kcat/KM for GSH are much lower as expected since GSH thiolate anion formation (and not the chemical reaction) contributes most to these parameters.

Figure 7.

Hammett plots of steady-state kinetic parameters for four electrophilic substrates 2,5-DCNB, CNBAM, CNAP, CDNB (left to right), and GSH at 5°C. (●) NEM activated MGST1 log kcat/KM, (○) Unactivated MGST1 log kcat/KM, (■) NEM activated MGST1, log kcat and (□) Unactivated MGST1 log kcat. All experiments were performed at 5 °C. (A) Saturating GSH concentration (5 mM) and varying concentration of the electrophile. (B) Saturating concentrations of electrophile (1 mM for all except CDNB which was at 0.5 mM) and varying GSH concentration. Slopes are indicated.

It is interesting to note that, even though there are proposed resting states and heterogeneously activated enzyme as well as possible product activation, reactivity does nevertheless contribute to the observed kinetic parameters (positive slopes between 0.5 and 4). This could be explained by the kinetics of the memory effects. For instance, more reactive substrates could more efficiently capture the enzyme during the short duration of catalytically augmented states whereas unreactive substrates would allow the enzyme to escape back into resting states, resulting in positive slopes in the Hammett plots. One very interesting aspect of the analysis is that activation of the enzyme (kcat) clearly takes place regardless of chemical reactivity of the electrophilic substrate. Intuitively, as activation affects the rate of thiolate formation and not the chemical conjugation step, less reactive substrates should be limited by chemistry. We suggest that the dynamics of interconversion to, or simply the activity of, the resting state can also be activated.

The Hammett plot data obtained here are very different from those obtained earlier at 30°C34. At the higher temperature kcat values were limited by GSH thiolate formation or chemical reactivity in a logical fashion allowing only activation of the more reactive substrates. Activation also for less reactive substrates, only at 5 °C, leads us to propose that the resting state is more peculiar to the low temperature experiments.

General discussion

MGST1 is an integral membrane enzyme facing the challenge of conjugating a hydrophilic substrate (GSH) with a hydrophobic electrophile entering the enzyme from the membrane phase (Figure 8)15.

Figure 8.

MGST1 representation with subunits in different color showing one GSH molecule covered by a schematic lid. The entry path for hydrophobic electrophiles from the membrane phase is shown (E). Membrane width is indicated by blue lines. Generated with Pymol from PDB entry 2H8A.

A cleft between subunits opens to the membrane phase allowing hydrophobic substrate access11. The cleft is covered by a loop that must open and close over GSH entering from the cytosol. This conformational dynamic step is rate limiting, if chemistry is reasonably rapid, and also greatly augmented when the enzyme is activated by chemical modification of this loop22. However, after activation the enzyme is also less stable, implying that there is a tradeoff between enzyme stability and catalytic efficiency. Thus, the need to have built in conformational flexibility for GSH binding comes at a cost. By having a pre-existing equilibrium favoring slow dynamics and stability a long half-life of the enzyme can be achieved. Once the stress sensing Cysteine-4933 becomes modified by a reactive electrophile however (which can only happen at acute toxicity when GSH is substantially depleted), efficiency is prioritized over enzyme stability. Whether GSH capture proceeds by an induced fit or conformational selection mechanism cannot be discerned from our data, however we would speculate that conformational selection for GSH binding can be more rapid in the more dynamic (activated) enzyme.

Conclusion

Activated MGST1 global kinetic behavior for one of the most commonly used GST substrates (CDNB) is well described by the individual processes GSH binding, thiolate anion stabilization, electrophilic substrate binding and chemical conjugation. Our observations also suggest that “unactivated” MGST1 is present in a dynamic equilibrium between activated and unactivated forms. The limited turnover pre steady-state experiment set up is the best system to examine binding and reaction rates for MGST1 as it mimics its state in vivo where the enzyme is already loaded with GSH due to the high intracellular concentrations (millimolar range).

Acknowledgments

We thank Gudrun Tibbelin for performing the enzyme preparation.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Carl Trygger Foundation and funds from Karolinska Institutet. Richard Armstrong was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM030910.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GST

Glutathione transferase

- MGST1

Microsomal glutathione transferase 1

- MAPEG

Membrane-Associated Proteins in Eicosanoid and Glutathione Metabolism

- LTC4S

leukotriene C4 synthase

- FLAP

5-lipoxygenase activating protein

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- 2,5-DCNB

2,5-dichloronitrobenzene

- CNBAM

4-chloro-3-nitro-benzamide

- CNAP

4-chloro-3-nitroacetophenone

- CDNB

1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene

Footnotes

Author Contributions

LS, RNA, and RM conceived the work and wrote the manuscript. LS, JÅ, AOW, CL, RS performed steady state data collection. LS and RM derived equations and analyzed the data. All authors commented on the final version of the manuscript.

Richard N. Armstrong sadly passed in 2015. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes JD, Pulford DJ. The glutathione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:445–600. doi: 10.3109/10409239509083491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins LG, Hayes JD. Mechanisms of induction of cytosolic and microsomal glutathione transferase (GST) genes by xenobiotics and pro-inflammatory agents. Drug Metab Rev. 2011;43:92–137. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.567391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson K, Jarvliden J, Gogvadze V, Morgenstern R. Multiple roles of microsomal glutathione transferase 1 in cellular protection: a mechanistic study. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1638–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park HS, Nam SH, Lee JK, Yoon CN, Mannervik B, Benkovic SJ, Kim HS. Design and evolution of new catalytic activity with an existing protein scaffold. Science. 2006;311:535–538. doi: 10.1126/science.1118953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W, Dourado DF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ, Mannervik B. Multidimensional epistasis and fitness landscapes in enzyme evolution. Biochem J. 2012;445:39–46. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honaker MT, Acchione M, Zhang W, Mannervik B, Atkins WM. Enzymatic detoxication, conformational selection, and the role of molten globule active sites. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:18599–18611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong RN. Structure, catalytic mechanism, and evolution of the glutathione transferases. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:2–18. doi: 10.1021/tx960072x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caccuri AM, Lo Bello M, Nuccetelli M, Nicotra M, Rossi P, Antonini G, Federici G, Ricci G. Proton release upon glutathione binding to glutathione transferase P1-1: kinetic analysis of a multistep glutathione binding process. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3028–3034. doi: 10.1021/bi971903g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakobsson PJ, Morgenstern R, Mancini J, Ford-Hutchinson A, Persson B. Common structural features of MAPEG -- a widespread superfamily of membrane associated proteins with highly divergent functions in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism. Protein Sci. 1999;8:689–692. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holm PJ, Bhakat P, Jegerschold C, Gyobu N, Mitsuoka K, Fujiyoshi Y, Morgenstern R, Hebert H. Structural basis for detoxification and oxidative stress protection in membranes. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:934–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez Molina D, Wetterholm A, Kohl A, McCarthy AA, Niegowski D, Ohlson E, Hammarberg T, Eshaghi S, Haeggstrom JZ, Nordlund P. Structural basis for synthesis of inflammatory mediators by human leukotriene C4 synthase. Nature. 2007;448:613–616. doi: 10.1038/nature06009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jegerschold C, Pawelzik SC, Purhonen P, Bhakat P, Gheorghe KR, Gyobu N, Mitsuoka K, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ, Hebert H. Structural basis for induced formation of the inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11110–11115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802894105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebert H, Jegerschold C. The structure of membrane associated proteins in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism as determined by electron crystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cebula M, Turan IS, Sjodin B, Thulasingam M, Brock J, Chmyrov V, Widengren J, Abe H, Mannervik B, Haeggstrom JZ, Rinaldo-Matthis A, Akkaya EU, Morgenstern R. Catalytic Conversion of Lipophilic Substrates by Phase constrained Enzymes in the Aqueous or in the Membrane Phase. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38316. doi: 10.1038/srep38316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson AD, McKeever BM, Xu S, Wisniewski D, Miller DK, Yamin TT, Spencer RH, Chu L, Ujjainwalla F, Cunningham BR, Evans JF, Becker JW. Crystal structure of inhibitor-bound human 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein. Science. 2007;317:510–512. doi: 10.1126/science.1144346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgenstern R. Microsomal glutathione transferase 1. Methods Enzymol. 2005;401:136–146. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgenstern R, Guthenberg C, Depierre JW. Microsomal glutathione S-transferase. Purification, initial characterization and demonstration that it is not identical to the cytosolic glutathione S-transferases A, B and C. Eur J Biochem. 1982;128:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgenstern R, Meijer J, Depierre JW, Ernster L. Characterization of rat-liver microsomal glutathione S-transferase activity. Eur J Biochem. 1980;104:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgenstern R, DePierre JW. Microsomal glutathione transferase. Purification in unactivated form and further characterization of the activation process, substrate specificity and amino acid composition. Eur J Biochem. 1983;134:591–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgenstern R, Svensson R, Bernat BA, Armstrong RN. Kinetic analysis of the slow ionization of glutathione by microsomal glutathione transferase MGST1. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3378–3384. doi: 10.1021/bi0023394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svensson R, Ålander J, Armstrong RN, Morgenstern R. Kinetic characterization of thiolate anion formation and chemical catalysis of activated microsomal glutathione transferase 1. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8869–8877. doi: 10.1021/bi0492511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ålander J, Lengqvist J, Holm PJ, Svensson R, Gerbaux P, Heuvel RH, Hebert H, Griffiths WJ, Armstrong RN, Morgenstern R. Microsomal glutathione transferase 1 exhibits one-third-of-the-sites-reactivity towards glutathione. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;487:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad S, Niegowski D, Wetterholm A, Haeggstrom JZ, Morgenstern R, Rinaldo-Matthis A. Catalytic characterization of human microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2: identification of rate-limiting steps. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1755–1764. doi: 10.1021/bi3014104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad S, Thulasingam M, Palombo I, Daley DO, Johnson KA, Morgenstern R, Haeggstrom JZ, Rinaldo-Matthis A. Trimeric microsomal glutathione transferase 2 displays one third of the sites reactivity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854:1365–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinaldo-Matthis A, Ahmad S, Wetterholm A, Lachmann P, Morgenstern R, Haeggstrom JZ. Pre-steady-state kinetic characterization of thiolate anion formation in human leukotriene C(4) synthase. Biochemistry. 2012;51:848–856. doi: 10.1021/bi201402s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakobson I, Askelof P, Warholm M, Mannervik B. A steady-state-kinetic random mechanism for glutathione S-transferase A from rat liver. A model involving kinetically significant enzyme-product complexes in the forward reaction. Eur J Biochem. 1977;77:253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson WW, Liu S, Ji X, Gilliland GL, Armstrong RN. Tyrosine 115 participates both in chemical and physical steps of the catalytic mechanism of a glutathione S-transferase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11508–11511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jemth P, Mannervik B. Fast product formation and slow product release are important features in a hysteretic reaction mechanism of glutathione transferase T2-2. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9982–9991. doi: 10.1021/bi983065b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Codreanu SG, Ladner JE, Xiao G, Stourman NV, Hachey DL, Gilliland GL, Armstrong RN. Local protein dynamics and catalysis: detection of segmental motion associated with rate-limiting product release by a glutathione transferase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15161–15172. doi: 10.1021/bi026776p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgenstern R, DePierre JW, Ernster L. Activation of microsomal glutathione S-transferase activity by sulfhydryl reagents. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;87:657–663. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)92009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson C, Piemonte F, Mosialou E, Weinander R, Sun TH, Lundqvist G, Adang AE, Morgenstern R. Kinetic studies on rat liver microsomal glutathione transferase: consequences of activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1247:277–283. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)00239-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busenlehner LS, Codreanu SG, Holm PJ, Bhakat P, Hebert H, Morgenstern R, Armstrong RN. Stress sensor triggers conformational response of the integral membrane protein microsomal glutathione transferase 1. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11145–11152. doi: 10.1021/bi048716k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgenstern R, Lundqvist G, Hancock V, DePierre JW. Studies on the activity and activation of rat liver microsomal glutathione transferase, in particular with a substrate analogue series. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6671–6675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keen JH, Habig WH, Jakoby WB. Mechanism for the several activities of the glutathione S-transferases. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:6183–6188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson KA, Simpson ZB, Blom T. FitSpace explorer: an algorithm to evaluate multidimensional parameter space in fitting kinetic data. Anal Biochem. 2009;387:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson KA, Simpson ZB, Blom T. Global kinetic explorer: a new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. Anal Biochem. 2009;387:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgenstern R, DePierre JW, Ernster L. Reversible activation of rat liver microsomal glutathione S-transferase activity by 5,5'-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) and 2,2'-dipyridyl disulfide. Acta Chem Scand B. 1980;34:229–230. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.34b-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimoji M, Aniya Y, Morgenstern R. Activation of Microsomal Glutathione Transferase 1 in Toxicology. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosialou E, Morgenstern R. Inhibition studies on rat liver microsomal glutathione transferase. Chem Biol Interact. 1990;74:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(90)90044-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]