Abstract

Elastin-like proteins (ELPs) are known to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation reversibly above a concentration-dependent transition temperature. Previous studies suggested that, as temperature increases, ELPs experience an increased propensity for type II β-turns. However, how the ELPs behave below the phase transition temperature itself is still elusive. Here, we investigate the importance of β-turn formation during the early stages of ELP self-association. We examined the behavior of two ELPs, a 150-repeat construct that had been investigated previously (ELP[V5G3A2-150] as well as a new 40-repeat construct (ELP40) suitable for nuclear magnetic resonance measurements. Structural analysis of ELP40 reveals a disordered conformation, and chemical shifts throughout the sequence are insensitive to changes in temperature over 20°C. However, a low population of β-turn conformation cannot be ruled out based on chemical shifts alone. To examine the structural consequences of β-turns in ELPs, a series of structural ensembles of ELP[V5G3A2-150] were generated, incorporating differing amounts of β-turn bias throughout the chain. To mimic the early stages of the phase change, two monomers were paired, assuming preferential interaction at β-turn regions. This approach was justified by the observation that buried hydrophobic turns are commonly observed to interact in the Protein Data Bank. After dimerization, the ensemble-averaged hydrodynamic properties were calculated for each degree of β-turn bias, and the results were compared with analytical ultracentrifugation experiments at various temperatures. We find that the temperature dependence of the sedimentation coefficient can be reproduced by increasing the β-turn content in the structural ensemble. This analysis allows us to estimate the presence of β-turns and weak associations under experimental conditions. Because disordered proteins frequently exhibit weak biases in secondary structure propensity, these experimentally-driven ensemble calculations may complement existing methods for modeling disordered proteins generally.

Introduction

Elastin was originally identified as the protein responsible for the reversible contraction of isolated skeletal muscle tissue at high temperatures (1). The elastic properties of elastin are mainly determined by its low-complexity hydrophobic domains, which primarily consist of four amino acids (valine, proline, glycine, and alanine) (2). Elastin-like proteins (ELPs) are a class of genetically-engineered proteins that are inspired by the hydrophobic domain of elastin and usually consist of five-residue repeats, VPGXG, in which the guest residue (X) can be any nonprolyl amino acid. At low temperatures, ELPs are thought to be disordered, with few conformational preferences (3). Above a particular temperature, termed the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) or the transition temperature (TT), ELPs undergo a reversible phase change (4, 5, 6) into liquid droplets composed of what is reported to be condensed, desolvated protein assemblies or aggregates. This reversible coacervation can be triggered not only by heat but also by other stimuli, such as salt (7), pH (8), and light (9). The TT of an ELP can also be tuned by the hydrophobicity of the guest residue and the number of unit repeats (10). The characteristic of reversible phase separation in ELPs has led to multiple applications, including the creation of new self-assembled materials (11), the design of molecular sensors (12, 13), and the delivery of drugs in biomedicine (14).

Although the relationship between ELP association, temperature, and concentration has been thoroughly studied, the mechanism of coacervation remains a subject of intense study. A variety of structural models have been proposed to explain the properties of elastin. Initially, Hoeve and Flory proposed that elastin follows the classical theory of rubber elasticity, in which the backbone chains have a Gaussian distribution of end-to-end chain lengths, and a narrowing of this distribution causes a decrease of entropy, which provides the source of the elasticity (15). Some experiments support this classic rubber elasticity model, which includes an isotropic structure (16), highly mobile chains (17, 18, 19), and conformational disorder of ELP (20, 21). However, random coil models of elastin are at odds with evidence from other experiments, which suggest a significant amount of structural propensity for β-turns and γ-turns. This evidence includes data from studies employing Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, circular dichroism (CD), and Raman spectroscopy (20, 22, 23, 24). Urry and co-workers postulated that elastin adopts a structurally ordered model, which assumes a random coil structure below the TT and a highly ordered motif β-spiral above the TT (25). Support for this model includes NMR, CD, and Raman studies, which indicate that ELP adopts type II β-turns at high concentrations and temperatures (5, 6, 8, 26, 27). This model, however, is not supported by solid-state NMR (21) studies on hydrated (VPGVG)n, which suggests that, below the TT, β-spirals do not form. Prior work, therefore, suggests that ELPs exhibit both disordered (random-coil) and ordered (type II β-turns) structural features below the TT, but the specifics of this equilibrium and dynamics remain poorly understood.

Because of their biophysical properties, ELPs have been proposed as a specialized class of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) (28). IDPs often have fractionally populated secondary structures (29, 30) similar to the β-turn bias proposed in ELPs. In addition, IDPs frequently have high proline content, corresponding to the ∼20% proline content observed in ELPs. This high proline content influences chain dimensions for both classes of proteins (31). The relationship between primary structure and IDP behavior has been studied by Pappu and co-workers, who found that sequence complexity can be used to identify distinct classes of IDPs with correspondingly different physical properties (32). ELPs have very few ionizable residues and exhibit moderately high hydrophobicity; they fall into the “globules and tadpoles” region of a Das-Pappu phase diagram, and they appear in the native folded region in an Uversky plot (33). It is therefore somewhat surprising that ELPs are highly disordered below TT, and whereas ELPs may share similarities with other IDPs, there are clear differences in behavior as well. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been used to study the reversible phase separation of ELPs. Because of current computational limitations, MD simulations have been used on short ELP sequences in water over timescales of 6–350 ns (34, 35, 36, 37). These simulations begin to explain the seemingly conflicting observations from experimental studies. Below the TT, small ELPs exhibit structural bias, deviating from a true random coil; on the other hand, whereas ELPs in simulations show increased turn propensity above the TT, the structure does not adopt an ideal β-spiral (34, 36, 37, 38).

Recently, a novel drug-delivery vector, ELP[V5G3A2-150] (sequence provided in Table S1), has been developed and extensively investigated for its structural, thermodynamic, and hydrodynamic properties (5, 6). The results show that, below the TT, ELP[V5G3A2-150] not only adopts a random coil but also forms temperature- and concentration-dependent β-turn structures. As temperature increases, ELP[V5G3A2-150] undergoes weak self-association, suggesting a role for β-turns in nucleation and coacervation. These observations raise several questions about ELP behavior:

-

1)

Can the presence of type II β-turns be reconciled with disordered behavior below the TT?

-

2)

How do increasing amounts of type II β-turn content alter the hydrodynamic properties below the TT?

-

3)

Does cis/trans prolyl isomerization significantly influence the ensemble properties?

-

4)

Are ensembles with type II β-turn content consistent with the weak self-association seen in sedimentation experiments?

To address these questions, we apply structure-biased Monte-Carlo simulations and protein docking to model the hydrodynamic measurements on the early stages of ELP interaction. We then test and refine these hypotheses using experimental data from NMR spectroscopy of analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC). Combined, the simulations and experimental data begin to address the questions above and suggest a mechanism for self-association and coacervation of ELPs.

Materials and Methods

ELP constructs and preparation

Two primary ELP constructs were used in this work. ELP40, a 40-repeat construct with unique residues at five positions throughout the sequence, was used for solution NMR characterization (Fig. 1 A). ELP[V5G3A2-150], a longer and more extensively characterized ELP (5, 6), was used for ensemble simulations and for AUC experiments. A single-site cysteine variant of ELP[V5G3A2-150] was also used for AUC experiments. The sequences for all proteins are given in Table S1. The gene for ELP40 was purchased commercially from GeneArt gene synthesis (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The sequence for ELP40 was cloned into a pET25b+ plasmid vector and transformed into Escherichia coli BLR(DE3) cells for protein expression. To maximize isotopically labeled protein yield, E. coli cells were gradually adapted from terrific broth to M9 minimal medium using a previously published method (39). Samples for NMR spectroscopy were produced in M9 minimal media with 15N ammonium chloride and (optionally) 13C glucose. Protein purification was performed as described previously (5, 40). Purified ELP40 was dialyzed extensively (12 h) into water, lyophilized, and stored at −80°C. ELP[V5G3A2-150] and a variant of ELP[V5G3A2-150] with cysteine at position 2 were expressed and purified as described previously (6).

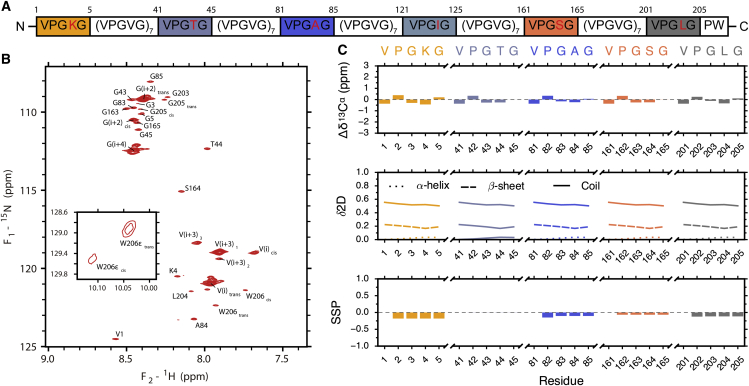

Figure 1.

ELP40 is highly disordered as a monomer. (A) A schematic representation of ELP40 highlights the six nonvalyl guest residues (red residues; blocks of guest-residue repeat units are highlighted with colored blocks). All guest repeat subunits could be assigned with the exception of the residues surrounding I124. (B) 1H-15N HSQC of ELP40 is shown. Chemical shifts exhibit a narrow dispersion, indicative of a disordered protein. General repeat subunits (VPGVG) are labeled with an index relative to the first valine, e.g., G(i+4). Resonances originating from cis-prolyl conformations are labeled with a subscript, e.g., W206cis. The single tryptophan sidechain resonance is shown in the inset. (C) Residue-specific disorder analysis from secondary chemical shifts (top), δ2D (middle), and secondary structure propensity (bottom) is shown. The results indicate ELP40 is predominantly disordered.

NMR spectroscopy

All samples for NMR experiments were prepared in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.0) to slow hydrogen exchange, 6% D2O, and 200 μM DSS. Protein concentrations were 1.0 mM in a total volume of 500 μL. All spectra were acquired on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III cryoprobe-equipped NMR spectrometer. Backbone and sidechain chemical shifts were assigned using 1H-15N HSQC, 1H-13C HSQC, HNCA, HNCO, CBCANH, CBCA(CO)NH, (H)CC(CO)NH, and TOCSY-1H-15N HSQC. Because of high proline content, (HACA)CON and (HACA)N(CA)CON spectra were also recorded (41). Nonuniform sampling (NUS) was used to acquire three-dimensional (3D) NMR spectra. Sampling schedules were generated by TopSpin (Bruker, Billerica, MA). A sampling schedule with 10% sparsity was applied to all 3D experiments except the HNCO experiment, in which 5% sparsity was used. Spectra were processed with NMRPipe, and the NUS spectra were reconstructed by SMILE (Sparse Multidimensional Iterative Lineshape Enhanced NUS) (42, 43). Processed NMR spectra were assigned and visualized using Sparky 3.115 (University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) (44).

Buried turn interaction search in the Protein Data Bank

The buried turn search was carried out on a nonhomologous protein list obtained from the PISCES server, which contains 2442 structures with a sequence identity ≤20%, resolution ≤1.6 Å, and R-factor ≤0.25 (45). Turns were classified based on dihedral angels; the Ramachandran plot was tiled into a series of 30° × 30° ø, ψ-grids (46, 47), and turns were identified based on previously described definitions (48). Solvent accessibility was assessed using NACCESS (49) by calculating the relative solvent accessibility. Amino acids were classified as buried if their relative solvent accessibilities were lower than a cutoff of 20% (50, 51). A β-turn was classified as buried if both of its central two residues were buried. Interacting β-turns were identified by calculating the geometric center of the backbone atoms from the four residues involved in the turn. If two centers were closer than 7 Å, those two turns were classified as interacting.

Ensemble simulations with different structural propensities

Monte Carlo calculations were performed using the LINUS simulation package to generate the structural ensembles, each with a differing fractional amount of type II β-turn content (52, 53). A set of 3D coordinates for ELP[V5G3A2-150] were generated as a linear chain conformation, which was used as the initial conformation for the simulation. One of two possible Monte Carlo moves was chosen for each cycle, either a type II β-turn move or a random coil move. Bias for β-turns was introduced by adjusting the relative weight of each move.

The β-turn move starts by selecting a VPGXG repeat at random in the ELP sequence (residues to ). Only the backbone ø, ψ values for residues to were set to a turn conformation; residue was not changed in the β-turn move. The logic for this turn move is based on prior work by Urry, which suggested that a turn forms between residues and of the VPGXG repeat (54). It is also based on the observation that Pro-Gly pairs frequently appear in the center of type II β-turns (48). The backbone dihedral angles (ø, ψ) of five turn-involved residues were taken from x-ray crystallographic data (55). To avoid steric clash and save computer time, adjacent β-turns were excluded for levels of bias <30%; that is, if any VPGXG repeat was already set to be a β-turn conformation, its neighboring repeats were not allowed to be β-turns as well. This approximation makes very little difference to the observed chain dimensions when the turn bias is low (<10%) (48) because the likelihood of forming a pair of neighboring repeats is correspondingly low (<20%). However, these neighboring repeats substantially influence simulation time, increasing the time from approximately 1 day to 1 week. If steric clash occurred, the ø, ψ angles of the two flanking residues ( and ) would be changed to random-coil conformation (random-coil moves are described below). Up to 10 pairs of ø, ψ values would be attempted for residues and before the β-turn move was rejected. After a successful (clash-free) β-turn move, all five repeat residues would be flagged as a turn to keep track of the overall turn content in any given structural snapshot. If either of the two core-turn residues ( or ) were selected for a successful random-coil move, all five residues would be marked as nonturn.

The random coil move starts by selecting a single residue at random throughout the entire ELP chain. Backbone ø, ψ angles for these residues were sampled from the protein coil library, with torsion angles specific to each type of residue (56). As described in the text, cis-Pro ω angles were introduced as necessary during this move as well. Successful, sterically allowed moves were applied to the structure and kept for future cycles of simulation.

Snapshots of ELP structures were saved after 223 successful β-turn or random-coil moves. This number of cycles was tested to ensure that on average every residue differed between structural snapshots. An ensemble of structures is the collection of structural snapshots, each with independent backbone torsion angles for each residue.

Convergence was determined by calculating the rolling average of structural properties and ensuring that doubling the size of the ensemble did not affect the calculations by more than 1%. As with previous LINUS-based simulations of disordered proteins (57, 58, 59), only steric clash was considered when generating structural snapshots using hard-sphere radii from the LINUS software (52). Sidechains were truncated beyond the Cβ atoms to speed generation of ensembles. A sidechain move set was introduced, but this did not influence the backbone dimensions or hydrodynamic properties of the ensembles (57, 59); it did, however, significantly increase the number of unsuccessful moves because of additional steric clash (by more than a factor of 10).

Structures with a β-turn content of >30% could not be easily generated because of steric clash. To generate these ensembles, we started with a β-spiral and selected a subset of turns at random to eliminate steric clash. Turn ø, ψ values were randomized by repeatedly applying the random-coil move described above, except the random-coil residues were selected based on a pregenerated list. If steric clash occurred, the residue would be temporarily changed back to the original value. The next iteration would randomly choose another candidate in the random-coil residue list. Structural snapshots were saved only when all designated residues in the list were changed to a random-coil conformation. The next structure was generated by returning to a β-spiral conformation and selecting a different subset of turns to randomize. This ensured that no residual random-coil conformations were repeated in consecutive structures. In this way, ensembles of many structures could be generated with a large, well-defined fraction of β-turn content. Convergence was verified as described above, and small changes to the starting β-spiral structure did not significantly affect the final chain dimensions of monomers or dimers.

ELP dimer generation

Type II β-turn positions in ELP monomers were confirmed by dihedral angles. As described above, a β-turn is defined as five consecutive residues, starting at the beginning of a VPGXG repeat, where the first four residues are locked into a turn conformation by the simulation algorithm. To generate ELP dimers, two conformers, which were randomly chosen from the monomeric ensemble, were placed in close proximity based on β-turn positions by using High-Ambiguity-Driven Protein-Protein Docking (HADDOCK) (60). In this process, HADDOCK optimized docking by randomizing orientations to minimize the rigid body energy. The dimer structures were adopted after HADDOCK’s rigid body energy minimization routine. This routine reorients the monomeric ELPs relative to one another, attempting to bury hydrophobic accessible surface area as well as to maximize turn-turn interactions. All five residues in the β-turn repeats were used as ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs), and multiple turns were allowed to interact during the formation of each dimer. Convergence was determined by doubling the number of structures and ensuring a change in RG of less than 1%, as described above.

Statistics of structural ensemble

The statistics of interest for each ensemble include the average RG and accessible surface area. The geometric radius of gyration for a structural was calculated by the following equation:

where N is the number of atoms in the structure, is the position of atom i in 3D coordinates, and is the geometric center of the molecule. Weighting by mass does not significantly change RG; therefore, the ensemble-averaged RG was directly obtained by averaging over all structures in the ensemble. The accessible surface area (ASA) was calculated using modules from the LINUS suite of programs (52, 53). The Shrake-Rupley algorithm (61) was used with 15,360 points per atom to calculate the ASA. The ΔASA of dimerization was calculated as the difference between the total monomer (both chains) and the dimeric ASA. Hydrophobic ASA was calculated by atom type, in which all backbone alpha carbon atoms as well as CH2 and CH3 sidechain carbon atoms were used for hydrophobic ASA calculations (48).

Hydrodynamics simulations

Two software packages, HYDROPRO and Solution Modeler (SOMO) (62, 63), were used to calculate sedimentation coefficients and hydrodynamic properties. For the HYDROPRO simulation, because of the time-consuming nature and the memory limit of shell modeling (INMODE 1 and 2), the bead model was chosen (INMODE 4). The atomic element radius, or bead size, was set as 5.5 Å based on considerations described in the text. The partial specific volume (VBAR) used in the simulation was 0.755, which was consistent with experimental data and the SOMO-predicted value. Default values were used for all other parameters. Because HYDROPRO does not directly report the frictional ratio , the following equation was used (64):

where is the molecular weight , is the partial specific volume of ELP, is the density of the standard solvent (water at 20°C), is Avogadro’s number, is the sedimentation coefficient obtained from the simulation, and is the viscosity of water at 20°C. For SOMO calculations, default values were used for all parameters. Both packages were run in batch mode.

Simulation of fast-exchange dimerization

To calculate how dimer exchange affects the hydrodynamic behavior of ELP[V5G3A2-150] below the TT, mixtures with a fixed ratio of dimers-to-monomers were generated by the Monte Carlo approach described above. For example, a 1% dimer mixture, which contains 1000 structures, will have 10 dimeric structures on average and 990 monomeric structures. The ensemble-averaged was calculated as the weight average over all structures in the 1000-structure mixture. Convergence was tested by regenerating the mixture 1000 times and plotting the histogram of average hydrodynamic properties.

Results

Examination of ELP secondary structure below and near the TT using NMR

A new ELP construct, ELP40, was designed for NMR experiments (Fig. 1). In this sequence, the normal guest residue (Fig. 1 A, bold) was chosen to be valine to lower TT and to maintain consistency with previous research (10). However, other guest residues were also included (red) to serve as structural probes that were assigned via NMR. This new construct was introduced for two main reasons. First, longer constructs such as ELP[V5G3A2-150] are difficult to study using NMR because of the large number of disordered residues. ELP40 reduces this complexity by shortening the sequence significantly. Although this property alone does not reduce overlap, it does reduce the intensity of valine and glycine signals relative to the guest residues, making it easier to detect signals from these residues while retaining a sequence that behaves similarly to ELP[V5G3A2-150]. Second, the unique guest residues incorporated into ELP40 enable monitoring of chain properties throughout the sequence. This construct is advantageous over a recently published ELP construct (ELP3) (65) in that it allows the solution behavior to be monitored at locations throughout the entire sequence.

NUS multidimensional NMR spectra (see Materials and Methods) were used to assign peaks and obtain the chemical shifts at three different temperatures: 288, 298, and 307 K (close to but still below the TT, which was measured by dynamic light scattering; Fig. S1). These temperatures were chosen to explore the prephase separation behavior of ELPs. Because of the highly repeated sequence in ELPs, peaks associated with VPGVG units exhibited a high degree of overlap. Given the high proline content of ELP, we asked whether the cis/trans prolyl isomerization might lead to a significant compactness. In both the 1H-15N HSQC (Fig. 1 B) and 1H-13C HSQC (Fig. S2), two sets of peaks were assigned, corresponding to VPGVG units in the cis and trans conformations. The backbone and sidechain assignments are available in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (http://bmrb.wisc.edu) under entry ID 27230. Integration of these peaks allows a direct comparison of cis and trans populations. When averaged over all proline resonances in the 1H-13C HSQC, we find that at 298 K, the ratio of cis:trans conformers is 7:93, and there is no significant change in this ratio as the temperature approaches TT (Table S2). This is in agreement with recent work by Reichheld et al., who used an approach based on chemical shift to investigate cis/trans prolyl isomerization (65).

Examination of the HSQC spectra revealed that the five nonvalyl guest residues (K4, T44, A84, S164, and L204) experienced different chemical environments and could be readily resolved; however, the I124 was unable to be assigned, which is most likely because of spectral overlap. Correspondingly, the glycine residues before and after these guest residues could also be fully assigned using standard triple-resonance NMR (Fig. 1 B). In addition, a CBCA(CO)NH experiment (66) was used to assign prolyl carbon chemical shifts for each of these repeat positions. Thus, the introduction of these guest residues resulted in nearly complete assignments for five (V) PGXG repeats throughout the entire ELP40 construct. The full listing of backbone and sidechain 1H, 15N, and 13C shift assignments of ELP40 is presented in Table S3. Secondary chemical-shift analysis shows only minor structural differences between the low and high temperatures (Figs. S3–S5). To identify potential conformational bias in the sequence, we used three common disorder analysis tools (secondary chemical shift (67, 68), δ2D (69), and secondary structure propensity (SSP) (29)) to quantify disorder in each of the ELP40 repeat subunits. We find that the five nonvalyl guest residues lack regular secondary structure and are predominantly random coils (Fig. 1 C). Overall, ELP40 behaves as a highly dynamic chain not only at lower temperatures but also near the TT (Figs. S3–S5). Although chemical shifts alone cannot rule out the presence of β-turn structure, the fact that no significant change in chemical shifts is observed with increasing temperature suggests that β-turn bias is small. Ensemble-based NMR approaches have been used to investigate bias in disordered proteins, but these approaches require additional data beyond chemical shifts, including scalar couplings and relaxation parameters (70, 71). Work is ongoing to collect this data and determine if NMR experiments can place an upper limit on β-turn content.

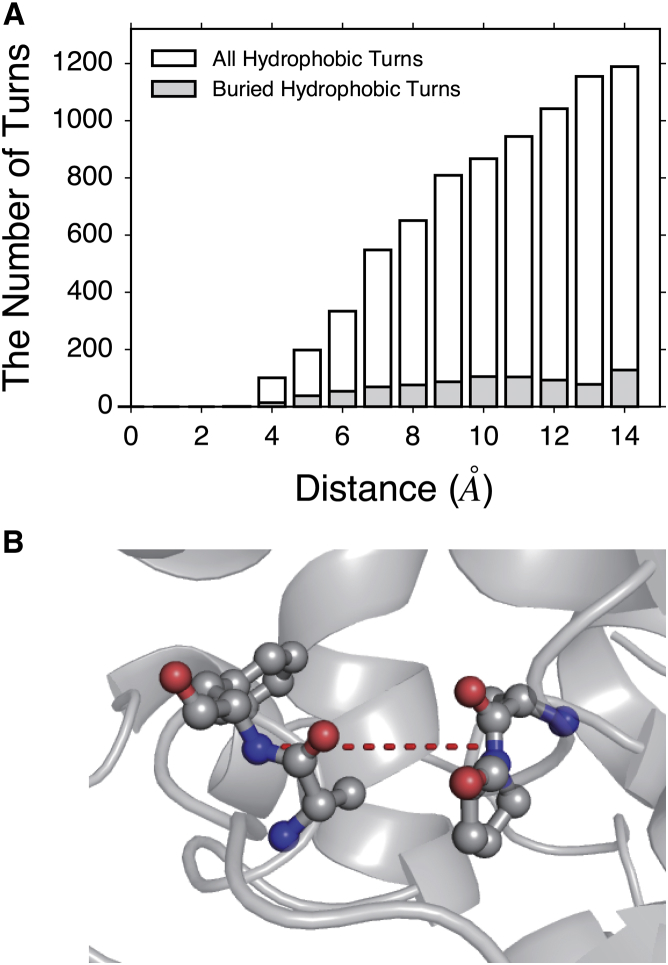

Ensemble simulation parameters: turn-turn interactions

Guided by our observations as well as the observations of others in the ELP literature, we sought to develop an experimentally driven structural model for early-stage ELP phase separation. To that end, we investigated the structural consequences of interacting β-turns in folded proteins. The β-turn is a common type of secondary structure that not only reverses the directional orientation of the protein backbone but also is implicated in molecular recognition and protein folding (48). Because they are topologically biased to expose protein surfaces, β-turns are frequent sites for protein-protein interaction. In ELPs, it has been argued that β-turns are the primary structural features both below and above TT (5, 6, 8, 26, 27, 65). Therefore, it is possible that ELP self-association is initiated at the β-turn positions. This hypothesis is supported by observed intermolecular nuclear Overhauser effect transfer between turn residues in an alternative ELP construct (65). To examine the structural feasibility of this hypothesis, we searched for turn-turn interactions in a subset of 2442 folded protein chains from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). This analysis was performed to determine if hydrophobic β-turns could be observed to interact in folded proteins, and if so, what the structural characteristics of that interaction might be. To select for nonredundant, high-quality sequences, we utilized the PISCES sever to identify protein chains from crystal structures with low sequence identity (<20%), high resolution (better than 1.6 Å), and refinement (R) factors better than 0.25 (45). β-turns were identified based on the ø, ψ angles of the central two amino acids. In most cases, the β-turns are highly solvent-exposed, contain hydrophilic residues, and participate in other secondary structural elements (e.g., alignment or joining of β-sheets). These higher-order features are likely not relevant in ELPs and were thus removed. Instead, only buried β-turns with hydrophobic residues were examined (see Materials and Methods). Using these criteria, buried, hydrophobic β-turns were frequently found to interact in the PDB (Fig. 2). A total of 635 (4.78%) pairs of hydrophobic turns were identified to interact in a data set of 13,272 turn pairs. If only buried turns are included, the entire data set shrinks to 2327 turn pairs, of which 212 (9.11%) are found to interact with each other (geometric distance from turn centers <7 Å). Different cutoff distances were also examined (Table S4). Although this analysis does not report on the energetics of turn-turn interactions, it does demonstrate that turn-turn interactions between hydrophobic residues do occur in folded proteins and are potentially relevant for initiating coacervation in ELPs.

Figure 2.

(A) A distance distribution between hydrophobic turns. As described in the text, the geometric centers are used to calculate the distance between two turns in a library of 2442 high-resolution, nonhomologous protein structures. (B) An example of a turn-turn interaction buried in a folded protein (PDB: 3HKW) is shown. The first turn (starting with Phe 415, followed by Ala-Pro-Thr) and the second (starting with Ser 470, followed by Ala-Phe-Ser) are separated by 3.4 Å. The dashed line shows the distance between geometric centers of two turns. To see this figure in color, go online.

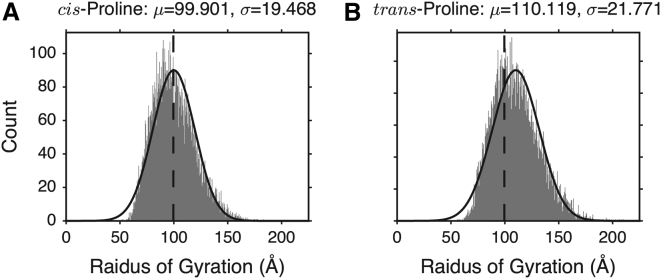

Ensemble simulation parameters: cis/trans proline content

An additional consideration in any structure-based model of ELP behavior is the cis/trans isomerization state of proline residues. In ELPs with proline-rich sequences (20% of residues in both ELP40 and ELP[V5G3A2-150]; Table S1), prolyl cis/trans isomerization may be important for the formation of a β-spiral and other secondary structural motifs in elastin. Recent single-molecule force spectroscopy (72) and NMR spectroscopy (73) shows that prolyl cis/trans isomerization in ELPs can cause local conformational changes that relate to elongation or contraction of the protein backbone. Here, two structural ensembles have been generated based on different proline isomerization models for ELP[V5G3A2-150] (Fig. 3). One model contains only cis-proline residues, and the other contains only trans-prolines. With the exception of Pro ω-torsion angles, all other backbone torsions could freely sample conformations from the protein coil library (56) to generate sterically allowed backbone conformations (see Materials and Methods for simulation details). The average radius of gyration (RG) from the cis-proline ensemble is 99.90 ± 0.19 Å (unless otherwise noted, the uncertainty is given as the SE of the mean from the structural ensemble), whereas the trans-proline ensemble gives an RG of 110.12 ± 0.22 Å. This result shows that altering the prolyl isomerization state of the ensemble can produce a measurable difference in chain dimensions. Based on chemical shifts in ELP40, the trans conformation is largely favored by a ratio 93:7 (cf. 9:1 in 65), and other work has shown that the isomerization rate is slow compared to the dynamic behavior in disordered proteins (74). It therefore is unlikely that all proline residues in a single ELP molecule will adopt an all-trans or all-cis conformation at any given time. On the other hand, a cis-prolyl ω-torsion does not eliminate the possibility of turn formation, as these repeats are still able to form type VI β-turns. Therefore, for the sake of simplicity in our model, we assume all proline residues are in the trans conformation.

Figure 3.

The RG histogram for either 100% of cis- (A) or 100% trans- (B) proline isomerization states in simulation of disordered ELP[V5G3A2-150] from 10,000 structures. For comparison, Gaussian distribution curves with the same mean and SD as those of the actual distribution are plotted as solid black lines. The black vertical dashed lines indicate the average RG calculated from the cis-prolyl ELP[V5G3A2-150] ensemble for comparison.

Ensemble simulations of monomeric ELP[V5G3A2-150]

Unlike most MD simulations, which examine the ensemble distribution of structures generated by a particular force field, our calculations specify a predetermined amount of β-turn content and examine the structural consequences of that constraint. In the traditional analysis, conformations below the TT are considered to be largely random (54); however, recent CD and laser Raman studies ((23); J. Benevides and J.C., unpublished data) suggest that there is a significant amount of type II β-turn even below the TT. Based on these observations, we generated a series of biased ensembles with different propensities of type II β-turn (1, 3, 5, 10, 30, 50, 70, 80, and 90%; Fig. 4). An ensemble with 0% II β-turn bias (in which backbone ψ, φ values were sampled entirely at random from the coil library) was also generated as a control. The ensembles with 0–30% bias each contained 10,000 structures. Higher degrees of turn bias were more difficult to generate because of steric clash, and fewer structures were used for these ensembles. Convergence of the simulations was confirmed by examining the rolling average RG and doubling the number of structures until the average changed by less than 1% (Figs. S6 and S7). Ensembles of structures are frequently used to model observables in IDPs (75, 76), and in all cases, our ensembles are as large as or larger than ensembles used in prior studies.

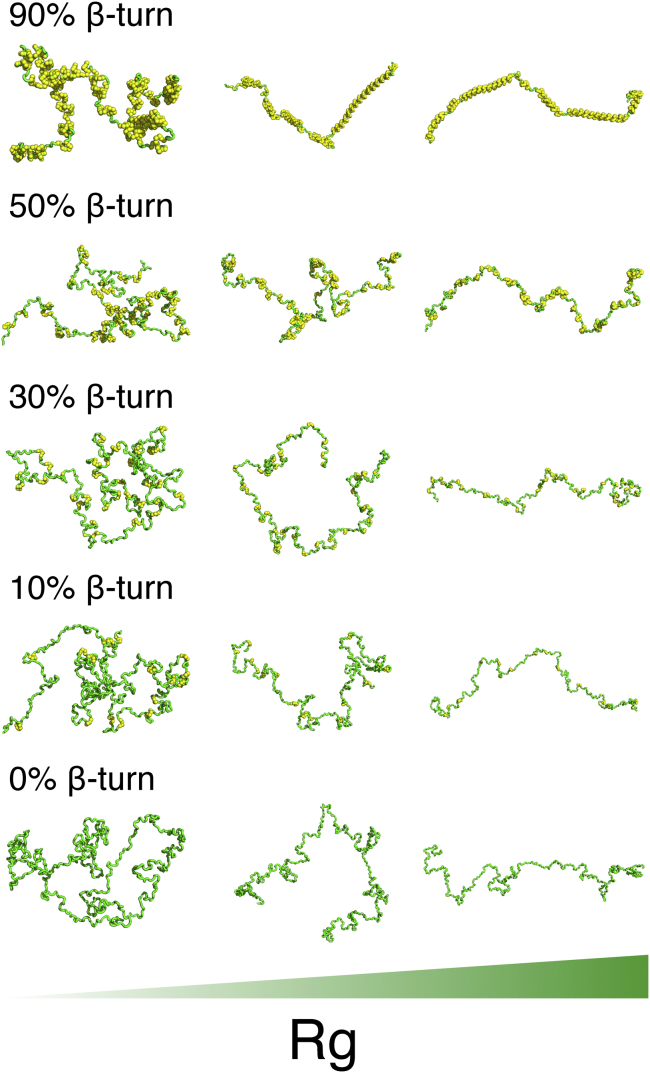

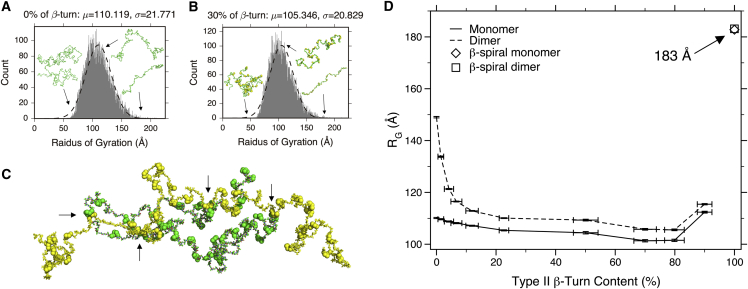

Figure 4.

Example structures with different propensities of β-turn. Residues involved in β-turns are highlighted with yellow Corey-Pauling-Koltun spheres. The structures in each column have a similar RG, ranging from 65 Å (left) to 180 Å (right). To see this figure in color, go online.

Although 30% (and up to 90%) of secondary structural bias (β-turns) has been introduced into ELP monomer structures, the overall structure still adopts a random-coil-like, extended shape (Figs. 4 and 5). More importantly, as the β-turn content is increased from 0 to 80%, only a 9 Å compaction, from 110.1 to 101.5 Å, is observed in the ensemble-averaged RG (Fig. 5 D). This compaction is significantly smaller than what is observed in the dimeric ensembles (discussed below). Globally, when examining RG alone, the behavior of monomeric ensembles with 0% β-turn bias and 30% bias is very similar. Even levels of bias as high as 50% have similar hydrodynamic properties (57). These results suggest that below the TT, an increase in β-turn structural contents will not affect ELP monomer behavior significantly.

Figure 5.

Radius of gyration histograms and representative ELP[V5G3A2-150] structures generated from ensemble simulations, 0% β-turn bias monomeric ensemble (A), and 30% β-turn bias monomeric ensemble (B). Different representative structures are shown in the inset for given values of RG. (C) is an example of dimeric ELP[V5G3A2-150] generated from two monomers, randomly selected from the 30% biased ensemble. The Corey-Pauling-Koltun spheres represent type II β-turn positions. In (C), the arrows point out where β-turn interactions have been introduced. In (D), the ensemble-averaged radius of gyration calculated from monomeric and dimeric ELP[V5G3A2-150] ensembles (after convergence; see legend) with different amounts of β-turn content is shown. The error bars in the plot represent the SE of the mean for RG (y axis) and the SD for the percentage of β-turn (x axis) within each ensemble.

Ensemble simulations of dimeric ELP[V5G3A2-150]

As discussed above, β-turns are a potential site for intermolecular interaction in ELPs. Here, we hypothesize that the initial ELP intermolecular interaction starts at β-turn positions, forming dimers (and higher-order oligomers) in fast exchange below the TT. To model the early stages of coacervation, two monomeric ELPs were brought into close proximity based on turn positions using the HADDOCK molecular docking suite (60). Type II β-turn positions in two monomeric ELP[V5G3A2-150] were input as AIRs, and the program selected some of these sites at random as final docking sites (Fig. 5 C). These docking processes were guided by rigid body energy minimization (77). To compare the results with unbiased structures (no β-turns), the docking for the 0% biased ensemble was carried out under random AIR definition mode, in which interacting residues are randomly defined on the accessible surface (77).

This docking protocol was used to generate 10 ELP dimeric ensembles with different amounts of type II β-turn content (up to 90%). Then, the ensemble-averaged radii of gyration were calculated from different ensembles (Fig. 5 D). The ensemble-averaged RG values observed from dimeric ensembles, unlike those from the monomeric ensemble, decrease sharply from 150 to 110 Å as more type II β-turn content is introduced. Compared to the monomeric ensemble, the dimeric ensemble exhibits a large change in RG as β-turn bias is increased. ELP coacervation is thought to involve a structural change above the TT (5, 6). Based on observations of the RG (50 vs. 9 Å), such a change is difficult to envision in monomeric structures alone; however, in dimers it is apparent that β-turn content can drive a significant alteration in chain dimensions.

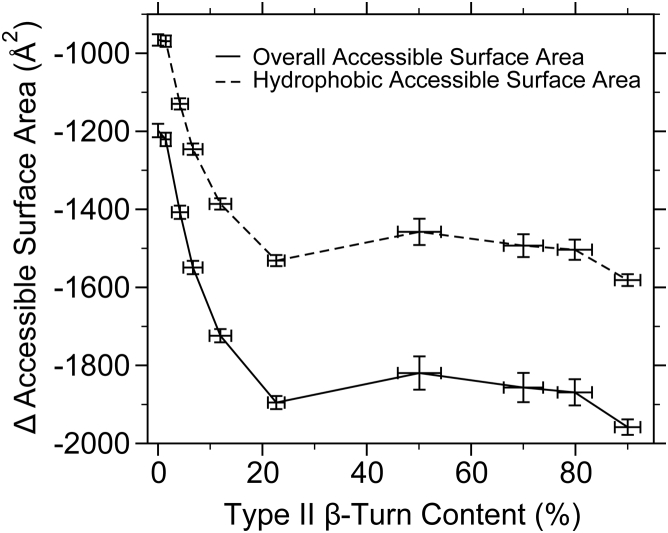

ASA and solvation energy

To understand the effect of β-turn content on the energetics of ELP association, hydrophobic ASA was calculated for all monomeric and dimeric ensembles with different type II β-turn biases. Here, the ASA for an ELP structure was calculated as a sum of ASA values over all residues for each monomer and dimer conformation. The ensemble-averaged ASA values have been plotted as a function of β-turn content (Fig. 6). To make a direct comparison between monomers and dimers, the ASA values for monomer ensembles were multiplied by 2. The dimer formation does lead to a decrease of the ASA (a negative ΔASA). This indicates that dimeric structures bury more hydrophobic surface exposure as more type II β-turn bias is introduced into the ensemble. Because most of the residues in ELP[V5G3A2-150] are hydrophobic, the overall ΔASA tracks closely with the hydrophobic ΔASA. The results from ASA calculations are consistent with the ensemble-averaged RG (Fig. 6), which shows that a small modulation of type II β-turn content can have a large impact on dimeric ELPs. Furthermore, these data suggest a direct relationship between buried hydrophobic surface in dimers and a favorable change in solvent entropy, ΔS, for both ELP self-association and ELP coacervation (see Discussion).

Figure 6.

Change in accessible surface area (ASA) (a negative value corresponds to ASA lost upon dimerization) as a function of type II β-turn bias. The error bars in the plot represent the SE of the mean.

Hydrodynamic simulation and ensemble verification

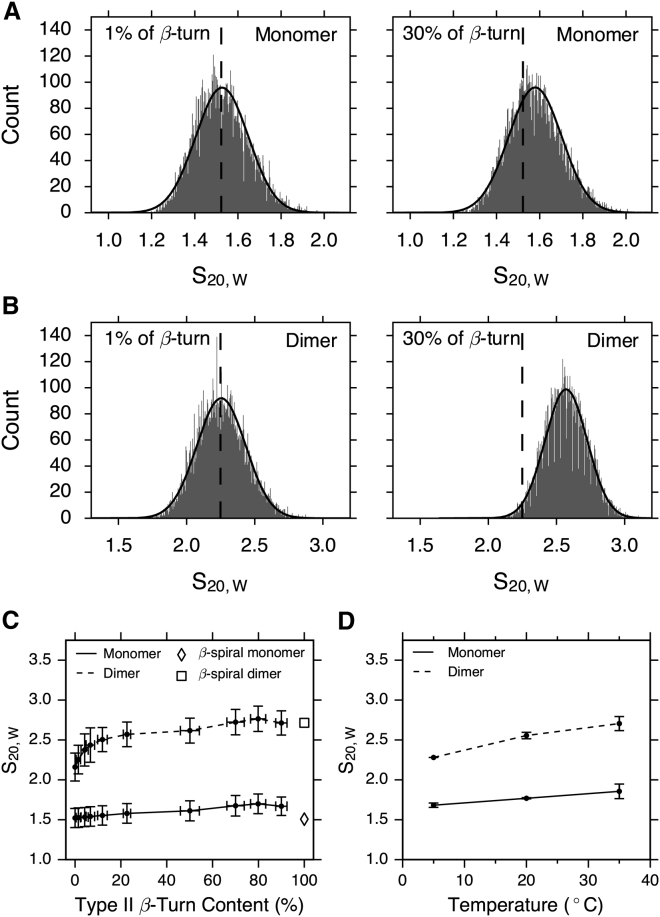

To test whether our model can yield reasonable hydrodynamic properties below the TT, HYDROPRO and SOMO were used to calculate sedimentation coefficients for monomeric and dimeric ensembles. HYDROPRO was operated in residue-level bead calculation mode, in which amino acid residues are replaced with a fixed-size bead (78). The size of the beads is critical for these calculations, and a similar software package (SOMO) was used for comparison. SOMO uses two beads to represent an amino acid residue, one for the backbone and another for the sidechain (62). Although much slower to complete, SOMO is less dependent on bead size because beads are automatically adjusted based on steric overlap. To compare these two programs, hydrodynamic calculations were carried out on 10,000 trans-prolyl conformers with varying type II β-turn content from 0 to 30%. Both HYDROPRO and SOMO were operated using default settings. Results from HYDROPRO yielded a slightly lower value compared to calculations from SOMO (e.g., 1.522 vs. 1.634 for the 0% β-turn ensemble; see Tables S5 and S6). However, the calculations are highly correlated (; Fig. S8), suggesting that both methods are producing a similar result, with a small systematic difference between the two methods. In addition, the HYDROPRO bead size was found to correlate with the predicted value of (Fig. S9). Therefore, the discrepancy between HYDROPRO and SOMO could be corrected by slight modifications to the HYDROPRO bead size (see Materials and Methods for details). Our final approach was to focus on the overall relationship between β-turn content and the predicted using HYDROPRO. This approach has the advantage of speed, as HYDROPRO performed significantly faster than SOMO (56 structures vs. 1 structure per minute).

Two representative distributions of for ELP[V5G3A2-150] with 0 and 30% β-turn contents reveal that histograms are broad and roughly Gaussian distributed (Fig. 7, A and B). The results of hydrodynamics calculations are summarized in Fig. 7 C. In addition to , HYDROPRO was used to calculate the Stokes radius , and the translational frictional ratio . These hydrodynamic parameters predictions are summarized as histograms (Figs. S10–S12). Comparing the 1% β-turn ensemble to the 30% ensemble reveals a more significant change in when dimers are formed between high-turn content structures. In addition, the ensemble-averaged increases more sharply in the dimeric ensembles as more β-turn is introduced (Fig. S12; Table S7), which suggests a more symmetric complex. In general, increasing β-turn content in monomeric ensembles does not significantly change ; however, similar to what was observed for RG, there is a significant shift observed for the dimeric ensembles (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Hydrodynamic calculations from ensemble simulations (A–C) and a comparison with experimental measurements (D). Two representative distributions of for ELP[V5G3A2-150] with different β-turn content (1% on the left and 30% on the right) from monomeric (A) and dimeric (B) ensembles are shown. The dashed line shows the average value from the 1% ensemble for comparison between 1 and 30% distributions. (C) Calculated are plotted as a function of type II β-turn content. Error bars in (C) represent the SD of values in each ensemble. (D) Sedimentation coefficients measured for ELP[V5G3A2-150] under low TCEP concentration (0.1 mM) are shown. Because this construct has a single cysteine residue, these conditions give rise to observable mixtures of monomer and disulfide cross-linked dimers (6). Error bars in (D) represent the SE of the mean from three independently prepared samples.

To test whether this model is predictive, sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments were performed on a cysteine-containing variant of ELP[V5G3A2-150] at a low Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) concentration (0.1 mM). This variant contains a cysteine at position 2 (Table S1). SV experiments were performed, as described previously (6). These conditions favor a mixture of monomers and cross-linked dimers that can be observed directly. Based on our previous observations, we hypothesize that a higher temperature in SV experiments roughly corresponds to a higher percentage of β-turn content in our calculations. Therefore, SV experiments were run at a series of temperatures below TT (5, 20, and 35°C; Fig. 7 D). Under these conditions, monomers and cross-linked dimers should have a similar amount of turn content, enabling us to compare our computational results with those of the experiment. ELP structures are highly disordered below the TT, so the difference between a cross-linked dimer and a noncovalent dimer is assumed to be negligible. The overall trend in SV is consistent with our calculations; the dimer is larger than the monomeric value, and this value increases as a function of temperature. β-turn content is believed to increase versus temperature (5, 6), and examining the ratio between dimer and monomer provides a computational approach for estimating the percentage of type II β-turns in the real structural ensemble. At 20°C, the ratio of dimer to monomer is 1.45 (Fig. 7 D); compared with Fig. 7 C, this corresponds to the same ratio seen at a β-turn bias of 5% in our calculations. Therefore, we estimate that, below TT, ∼5% of residues in ELPs sample a β-turn conformation. The experimental ratio increases to 1.5 at 35°C for ELP[V5G3A2-150] (Fig. 7 D), corresponding to a prediction of 30% β-turn bias just below the TT for these experimental conditions. It is worth noting that the simulated ratio varies from 1.33 (0%) to 1.68 (80%), which is consistent with significant compaction of the dimers at high β-turn bias. The experimental ratios increase from 1.33 (5°C) to 1.45 (20°C) to 1.50 (35°C), corresponding to a moderately increasing β-turn bias.

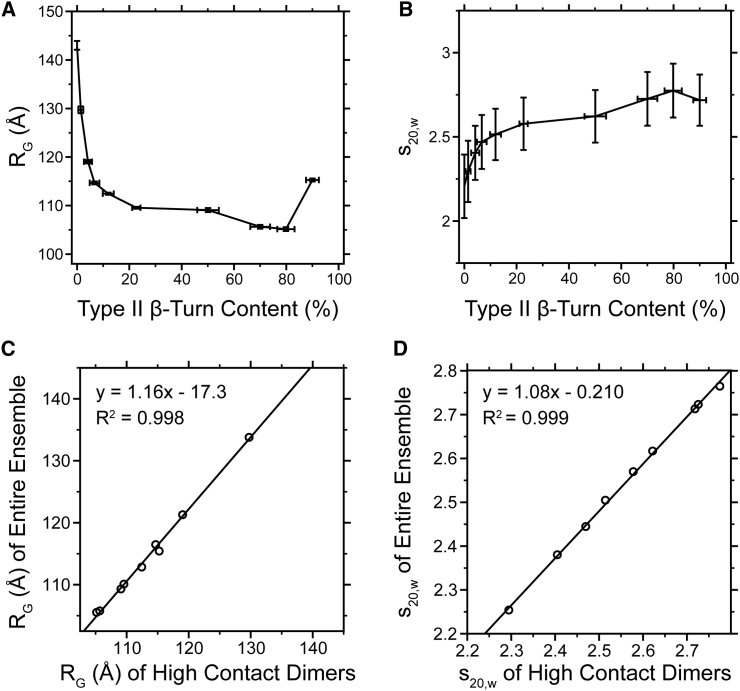

It is possible that the compaction observed above results simply from an increased number of intermolecular contacts in structures with high β-turn content. To test whether this is the case, we reanalyzed our ensembles, keeping the overall number of contacts fixed. The Cα-Cα distances were calculated between all of the dimer structures used in the original analysis, and a distance within 6 Å or less was used to define an intermolecular contact event. Thus defined, the average number of intermolecular contacts in the original ensemble with a 90% β-turn bias was 23. Correspondingly, subset ensembles were generated for all other amounts of turn bias, ensuring that the number of intermolecular contacts was 23 or greater, and dimer structures with fewer than 23 contacts were removed. In this way, we generated a new set of ensembles, each having a similar number of contacts. The subset of ensembles exhibit an identical trend for the average RG and values, and their properties are highly correlated with the original ensembles in which the number of contacts was not controlled (; Fig. 8). Moreover, the histograms of the high-contact ensembles are indistinguishable from the original histograms (Fig. S13). Thus, even when all dimers contain a similar number of contacts, the same changes in RG and are observed as turn content is increased. This strongly suggests that that the increase in β-turn bias (and not additional hydrophobic contacts alone) is necessary to generate the increase in compaction observed for the dimer structures.

Figure 8.

Ensemble-averaged RG (A) and (B) values from subsets of dimers with a controlled number of intermolecular contacts. In addition to exhibiting the same trend seen for dimers in Figs. 5D and 7C, the values themselves are highly correlated ((C and D), respectively).

Simulation of fast-exchange dimerization

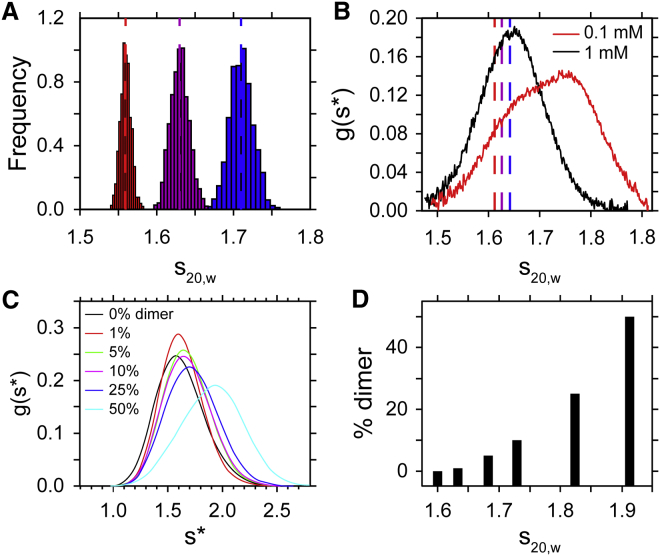

Previous work has shown that ELP[V5G3A2-150] undergoes weak self-association with increasing temperature (5, 6). Here, we considered how weak self-association would influence hydrodynamic properties of an equilibrium population of monomers and dimers in AUC SV experiments. To assess this weak dimerization, an artificial ensemble of both monomeric and dimeric ELPs was constructed based on previous simulations. From this ensemble of mixed states, the observed for a particular ensemble can be calculated as the mass-weighted average of . This value of can be directly compared to the maximum of the distribution determined from an SV experiment. In an SV experiment, the distribution quantifies the sedimentation coefficients in a mixture of sedimenting species. The maxima in the distribution correspond to the sedimentation coefficients most likely present in an SV experiment. The width of the distribution contains information about the diffusion coefficient, heterogeneity, and interactions of the sedimenting species; this width reflects how the sedimentation boundary changes over time, and it is not easily determined from our ensemble calculations without kinetic information about the dynamics of the ensemble or information about reversible interactions. Nevertheless, comparing the weight-average from our ensembles and the maximal value of the distribution can produce meaningful results.

We examined mixed-state (monomer-dimer) ensembles to estimate the fraction of dimer observed in SV experiments. In these calculations, the β-turn bias was fixed at 5%, corresponding to a temperature of 20°C. The dimer:monomer ratio was then varied to investigate how the average was affected (Fig. 9 A). For comparison, SV experiments were performed on the single-site cysteine variant of ELP[V5G3A2-150], which contains a mixture of both monomeric and dimeric forms (Fig. 9 B, black curve). Experiments were also performed at high TCEP concentration, where no cross-linking is anticipated (Fig. 9 B, red curve). It is clear from the cross-linked (red) experiments that incorporation of dimers shifts the distribution to the right relative to the experiments performed without cross-linking (black). However, even without cross-linking, the experimental curve contains some self-association.

Figure 9.

Histograms of the distribution of the average values for 1000 different ensembles (A) with varying fractions of dimers. 1% (red), 5% (purple), and 10% (blue) dimer distributions are shown. The distribution of average values taken from 1000 different ensembles is much narrower than the actual distribution because the distribution includes additional information on molecular interactions. Dashed vertical lines represent the weight-average values corresponding to each distribution. (B) An experimental curve for ELP[V5G3A2-150] under conditions of 1 mM TCEP (black; no cysteine cross-linking) and 0.1 mM TCEP (red; partially cross-linked) is shown. The calculated ensemble with 10% dimer roughly matches the maximum observed for the experiment with no cross-linking. (C) A simulation of sedimentation velocity monomer-dimer equilibrium with SEDANAL (99) is shown to demonstrate increasing amounts of dimer. Simulations were performed with the following parameters: a total ELP concentration of 1 mg/mL, 60 K rpm, ra at 5.9 cm, rb at 7.2 cm, s1 = 1.6 s (monomer), s2 = 2.4 s (dimer), and an increasing equilibrium constant to represent a temperature-dependent increase in ELP association. (D) The weight-averaged sedimentation coefficients from (C) is shown, plotted as a function of percent dimer and presented as a bar graph to mimic the presentation in (A). (C) and (D) neglect nonideality, which can be significant for IDPs. Representative distributions of values from individual ensembles in (A) are given in Fig. S14.

Initially, the weight-averaged from our calculations with 0% of dimer did not agree with the experimental maximum of for non-cross-linked ELPs. By systematically increasing the dimer:monomer ratio, a corresponding increase was observed in the weight-averaged , increasing the agreement between the two values. Good agreement between calculations and experiment was observed when the dimer fraction was roughly 10% (Fig. 9 B, the blue dashed line corresponds to the center of the blue 10% dimer distribution in Fig. 9 A). This suggests that ∼10% of the ELP ensemble at 20°C samples higher-order oligomeric states.

In general, the experimental ratios of agree with the simulated hydrodynamic results derived from bead modeling. However, there are a number of caveats to the comparisons presented in Fig. 9. First, the simulated data do not exhibit thermodynamic nonideality, which slows experimental values. Whereas the experiments were performed at low concentration to minimize nonideality, some degree of nonideality is inevitable in any self-interacting system. Second, temperature-dependent weak association is occurring in the experimental distributions that in part accounts for the broadening and increase in . However, nonideality and association mask one another, with nonideality being more significant at low temperatures and association being more significant at higher temperatures. This is consistent with the entropic nature of the ELP association and phase change. At 35°C, and are clearly concentration dependent and shift to higher values (5, 6), which is consistent with our simulations. Third, structural heterogeneity in the ensemble (Figs. 4 and 5) may not be reflected in the distribution if rapid exchange on the timescale of the AUC experiment occurs. Nevertheless, the width of the experimental distribution is consistent with that of the simulations (Figs. S10–S12). To demonstrate these features, ideal weak association was simulated using SEDANAL (Figs. 9, C and D) to show both the shift in the distribution and the average of the distribution with increasing amounts of dimer. The SEDANAL analysis reproduces the same trend as that in our structural ensembles, showing an increase in as the dimer fraction increases (Fig. 9 D). At the same time, this analysis also captures the broadening expected in experimental curves (Fig. 9 C).

Discussion

ELPs have been proposed as a potential model for studying IDPs (28) not only because of their repetitive and low complexity sequences but also because of their disordered structure below the TT. Our calculations demonstrate that, even when biased to contain 50% type II β-turn content, the ELP ensemble still possesses random-coil chain dimensions. Stated differently, a significant amount of β-turn content (local organization) would not necessarily conflict with ELPs having a globally disorganized tertiary structure (57). Because of this, using traditional “random-coil” approaches to model ELPs may be inappropriate, as they fail to capture local organization in the sequence. A “statistical-coil” model has been proposed to sample conformations more accurately in the unfolded state of proteins (56, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84). In the case of ELPs, however, because of the β-turn content, it is reasonable to include this structural bias into structural calculations, as we have done here. We have also used dimerization of ELPs to mimic weak self-association in ELPs in the early stages of coacervation, assuming monomeric ELPs interact at β-turn positions. Because increasing temperature induces a higher percentage of type II β-turns, a more compact dimer will be formed with increasing temperature. This hypothesis is supported by calculations of ASA, and it is in line with experimental AUC data. Our results suggest that a small fraction of dimer can lead to a significant shift in the sedimentation coefficient.

These structural features—β-turns and self-association—affect the hydrodynamic properties of ELPs, and they are more likely to change systematically during ELP association and phase separation. Previously, the presence of weakly self-associating monomers and type II β-turns were proposed by AUC and CD experiments, but it was difficult to quantify their significance in the absence of a structural model. Here, we propose a method based on ensemble calculations in which both type II β-turn content and self-association are considered. By comparing the simulation to SV data, we can then extract the percentage of β-turn content and weak association in the actual structures. Given that structural bias has also been observed in many IDPs (85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90), this biased approach to ensemble calculation could potentially be applicable to IDPs generally.

Previous research suggests that ELPs are soluble in aqueous solutions below their LCST, but these polymers undergo hydrophobic collapse and phase separation at temperatures greater than their LCST (91). This collapsed structure has for years been hypothesized to be a β-spiral (25) based upon model building from a crystal structure of a trimeric pentapeptide. However, no one has ever observed this spiral structure in solution. Numerous MD simulations (36, 37, 38) have started with a β-spiral that is not stable and quickly reverts to a random-coil structure with propensity to make β-turns and/or β-sheets above the TT. These observations are commonly quoted to reject the β-spiral model. In our ensemble calculations, we have approached the question in a different way. We simulate structures with increasing amounts of β-turn and then ask how this bias impacts the hydrodynamic attributes of a monomer and dimer ensemble. We discover that ELP monomers, even up to 90% β-turn, behave essentially like random coils and exhibit little compaction, as viewed by distributions of , RH, and (Fig. S9). Comparing monomers at 90% turn content to those with 0% turn content, increases by 9.7%, whereas RH and decrease by 8.9%. Alternatively, for simulated dimers, the changes are substantially larger. In an ensemble with 90% turn content, increases by 25.6% compared to an ensemble with 0% turns, whereas RH and decrease by 20.6%. More importantly, when β-turn content is increased from 0 to 30%, monomers exhibit a minimal change in hydrophobic ASA (−56 Å2), whereas dimers lose 1581 Å2 of ASA upon dimer formation (Fig. 6). Loss of hydrophobic surface is a thermodynamic driving force for entropically favored processes. For example, burial of nonpolar and polar ASA ( and ) is related to changes in heat capacity, (−439 22 cal/mol K at 30% turn, using the ensemble SEM to estimate the uncertainty) (92), and changes in heat capacity can be related to an entropic force because of the hydrophobic effect, = 111 eu at 30% or +34 kcal/mol at 35°C (93). This hydrophobic driving force results from release of solvent water as hydrophobic surfaces are buried during dimerization, which contributes to an increase in overall entropy. Thus, our simulations demonstrate that the association of ELP with significant amounts of β-turn formation can provide a driving force for hydrophobic collapse and coacervation. This process is opposed by loss of rotational-translational freedom . For rigid bodies, is often assigned values between 20 and 50 eu, but the dynamic, random-coil behavior of ELPs, even at high β-turn bias, suggests that this value could be much less. Furthermore, β-turn formation should also provide an unfavorable conformational entropic contribution and must be overcome in the overall energetics of coacervation. Even at the low concentrations measured in CD experiments, β-turn formation increases with elevated temperature, suggesting that β-turn formation and ensemble heterogeneity (Fig. 4) are intrinsic to ELP structure.

We have previously demonstrated that ELP undergoes weak, nonideal, and temperature-dependent oligomer formation (5, 6). We and others have shown by CD (5, 6) and in this work by NMR (Fig. 1) that ELPs undergo temperature-dependent β-turn formation (5, 6, 8, 26, 27). We hypothesized that the two processes were coupled in some way. ELP coacervation exhibits a positive enthalpy change (ΔH ∼38–50 kcal/mol) (5, 6). The temperature-dependent oligomer formation previously reported is also consistent with a positive enthalpy change (ΔH ∼8–12 kcal/mol). Thus, we suggest that entropically driven oligomer formation, stabilized by the burial of hydrophobic ASA, is one of the significant driving forces of ELP coacervation. As suggested numerous times previously, the phase change occurs when ELP-solvent interactions become less stable than ELP-ELP interactions. This is not a new proposal. Years ago, Urry suggested that thermodynamically driven shedding of solubilized water molecules and hydrophobic collapse of the polypeptide due in part to intra- and intermolecular ordering of ELP accounted for the coacervation process (94). Recently, Chilkoti’s group (37) used MD simulations to look at (VPGVG)18 interactions and suggested a temperature-dependent attractive interaction between two molecules. They concluded that a competition between peptide-peptide and peptide-water interactions, described as an abrupt change in hydrated water, is relevant to the LCST phase behavior of ELP. Our experimental results and calculations provide a possible mechanism for this process. Consistent with our model, a recent NMR study on ELP3 (composed of 21 repeat units) also found evidence for transient β-turns in both monomeric and coacervated ELP states (65).

The phase change is often represented by a solubility plot of TT versus log[ELP] and exhibits a straight-line behavior over many orders of magnitude of concentration (5). Even at concentrations well below the K (M−1) for self-association (e.g., Kiso of 5000–7500 M−1 at 35°C), ELP will phase change at higher temperatures. This suggests that the loss of solubility of ELP, in conjunction with β-turn formation and an abrupt change in hydrated water, may nucleate microstructures that concentrate ELP and stabilized oligomers or aggregates, as the field prefers to call them. Membraneless organelles in general are known to concentrate their protein or ribonuclear protein contents 100 times or more (95). Other systems clearly require high affinity and modular or multivalent components (96, 97, 98) in addition to temperature-dependent solubility changes to nucleate the phase change. The model we propose involves numerous hydrophobic contacts that can dynamically reorganize in a modular manner, and it is the sum of many contacts that contributes to the buried surface and the driving force for coacervation. Thus, our approach provides a means to model the initiation of phase-separated droplets.

Conclusions

To summarize, we propose a structural model to describe the early stages of self-association during the ELP phase separation. Monomeric and dimeric ensembles are generated with propensities of β-turn, and the properties of each ensemble are examined. We find that β-turn bias alone is insufficient to drive a significant change in ELP properties, but if dimerization is also included in the model, turns can dramatically alter the RG and hydrophobic ASA. By comparing it with AUC experiments, we estimate that, at 20°C (below the TT), the ELP[V5G3A2-150] construct contains ∼5% β-turn content and 10% concentration-dependent high-order oligomers. This observation is supported by NMR experiments on an ELP40 construct that allows measurement of chemical properties throughout the 40-repeat protein. Based on our calculations, we suggest that entropically driven oligomer formation stabilized by the burial of hydrophobic ASA is one of the significant driving forces of ELP coacervation. Experimentally driven ensemble calculations such as these may provide an approach to model liquid-liquid phase separation in biological systems.

Author Contributions

Y.Z., V.Z.-R., J.J.C., and N.C.F. designed the research. Y.Z., V.Z.-R., C.J.P., N.A.E., G.L.B., J.J.C., and N.C.F. performed the research. Y.Z., J.J.C., and N.C.F. analyzed the data and wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R15GM113152 (to N.C.F.) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL121527 (to G.L.B.). This work was also supported by the University of Mississippi Medical Center AUC Facility. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: James Cole.

Footnotes

Fifteen figures and seven tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30301-1.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Brodie T.G., Richardson S.W.F. A study of the phenomena and causation of heat-contraction of skeletal muscle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1899;191:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vrhovski B., Weiss A.S. Biochemistry of tropoelastin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;258:1–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urry D.W. Free energy transduction in polypeptides and proteins based on inverse temperature transitions. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1992;57:23–57. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(92)90003-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y., Trabbic-Carlson K., Cremer P.S. Aqueous two-phase system formation kinetics for elastin-like polypeptides of varying chain length. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2192–2199. doi: 10.1021/bm060254y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons D.F., Le V., Correia J.J. Structural and hydrodynamic analysis of a novel drug delivery vector: ELP[V5G3A2-150] Biophys. J. 2013;104:2009–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyons D.F., Le V., Correia J.J. Effect of basic cell-penetrating peptides on the structural, thermodynamic, and hydrodynamic properties of a novel drug delivery vector, ELP[V5G3A2-150] Biochemistry. 2014;53:1081–1091. doi: 10.1021/bi400955w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho Y., Zhang Y., Cremer P.S. Effects of Hofmeister anions on the phase transition temperature of elastin-like polypeptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:13765–13771. doi: 10.1021/jp8062977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urry D.W. Molecular machines: how motion and other functions of living organisms can result from reversible chemical changes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993;32:819–841. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strzegowski L.A., Martinez M.B., Tirrell D.A. Photomodulation of the inverse temperature transition of a modified elastin poly(pentapeptide) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:813–814. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chilkoti A., Dreher M.R., Meyer D.E. Design of thermally responsive, recombinant polypeptide carriers for targeted drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002;54:1093–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreher M.R., Simnick A.J., Chilkoti A. Temperature triggered self-assembly of polypeptides into multivalent spherical micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:687–694. doi: 10.1021/ja0764862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raphel J., Parisi-Amon A., Heilshorn S. Photoreactive elastin-like proteins for use as versatile bioactive materials and surface coatings. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:19429–19437. doi: 10.1039/C2JM31768K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassouneh W., Nunalee M.L., Chilkoti A. Calcium binding peptide motifs from calmodulin confer divalent ion selectivity to elastin-like polypeptides. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2347–2353. doi: 10.1021/bm400464s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bidwell G.L., III, Raucher D. Cell penetrating elastin-like polypeptides for therapeutic peptide delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010;62:1486–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeve C.A., Flory P.J. The elastic properties of elastin. Biopolymers. 1974;13:677–686. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aaron B.B., Gosline J.M. Optical properties of single elastin fibres indicate random protein conformation. Nature. 1980;287:865–867. doi: 10.1038/287865a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torchia D.A., Piez K.A. Mobility of elastin chains as determined by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;76:419–424. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debelle L., Alix A.J. The structures of elastins and their function. Biochimie. 1999;81:981–994. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)00221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bochicchio B., Floquet N., Tamburro A.M. Dissection of human tropoelastin: solution structure, dynamics and self-assembly of the exon 5 peptide. Chemistry. 2004;10:3166–3176. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao X.L., Hong M. Structure distribution in an elastin-mimetic peptide (VPGVG)3 investigated by solid-state NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4199–4210. doi: 10.1021/ja036686n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pometun M.S., Chekmenev E.Y., Wittebort R.J. Quantitative observation of backbone disorder in native elastin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7982–7987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas G.J., Jr., Prescott B., Urry D.W. Raman amide bands of type-II β-turns in cyclo-(VPGVG)3 and poly-(VPGVG), and implications for protein secondary-structure analysis. Biopolymers. 1987;26:921–934. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiersen H., Clarke A.R., Rees A.R. Short elastin-like peptides exhibit the same temperature-induced structural transitions as elastin polymers: implications for protein engineering. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;283:255–264. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolini C., Ravindra R., Winter R. Characterization of the temperature- and pressure-induced inverse and reentrant transition of the minimum elastin-like polypeptide GVG(VPGVG) by DSC, PPC, CD, and FT-IR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1385–1392. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkatachalam C.M., Urry D.W. Development of a linear helical conformation from its cyclic correlate. β-Spiral model of the elastin poly(pentapeptide) (VPGVG)n. Macromolecules. 1981;14:1225–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urry D.W., Trapane T.L., Prasad K.U. Sequential polypeptides of elastin: cyclic conformational correlates of the linear polypentapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:2080–2089. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urry D.W. Physical chemistry of biological free energy transduction as demonstrated by elastic protein-based polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:11007–11028. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts S., Dzuricky M., Chilkoti A. Elastin-like polypeptides as models of intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:2477–2486. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh J.A., Singh V.K., Forman-Kay J.D. Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between α- and γ-synuclein: implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2795–2804. doi: 10.1110/ps.062465306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen M.R., Houben K., Blackledge M. Quantitative conformational analysis of partially folded proteins from residual dipolar couplings: application to the molecular recognition element of Sendai virus nucleoprotein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8055–8061. doi: 10.1021/ja801332d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh J.A., Forman-Kay J.D. Sequence determinants of compaction in intrinsically disordered proteins. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2383–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das R.K., Pappu R.V. Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13392–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304749110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uversky V.N., Gillespie J.R., Fink A.L. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins. 2000;41:415–427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::aid-prot130>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B., Alonso D.O.V., Daggett V. The molecular basis for the inverse temperature transition of elastin. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:581–592. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rousseau R., Schreiner E., Marx D. Temperature-dependent conformational transitions and hydrogen-bond dynamics of the elastin-like octapeptide GVG(VPGVG): a molecular-dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1393–1407. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krukau A., Brovchenko I., Geiger A. Temperature-induced conformational transition of a model elastin-like peptide GVG(VPGVG)(3) in water. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:2196–2202. doi: 10.1021/bm070233j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li N.K., García Quiroz F., Yingling Y.G. Molecular description of the LCST behavior of an elastin-like polypeptide. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:3522–3530. doi: 10.1021/bm500658w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li B., Alonso D.O., Daggett V. Hydrophobic hydration is an important source of elasticity in elastin-based biopolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11991–11998. doi: 10.1021/ja010363e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W., Dreher M.R., Chilkoti A. Tracking the in vivo fate of recombinant polypeptides by isotopic labeling. J. Control. Release. 2006;114:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bidwell G.L., III, Raucher D. Application of thermally responsive polypeptides directed against c-Myc transcriptional function for cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1076–1085. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bastidas M., Gibbs E.B., Showalter S.A. A primer for carbon-detected NMR applications to intrinsically disordered proteins in solution. Conc. Magn. Reson. A. 2015;44:54–66. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ying J., Delaglio F., Bax A. Sparse multidimensional iterative lineshape-enhanced (SMILE) reconstruction of both non-uniformly sampled and conventional NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR. 2016;68:101–118. doi: 10.1007/s10858-016-0072-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goddard T.D., Kneller D.G. University of California, San Francisco; San Francisco, CA: 2008. SPARKY 3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang G., Dunbrack R.L., Jr. PISCES: a protein sequence culling server. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1589–1591. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srinivasan R., Rose G.D. A physical basis for protein secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14258–14263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gong H., Fleming P.J., Rose G.D. Building native protein conformation from highly approximate backbone torsion angles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16227–16232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508415102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose G.D., Gierasch L.M., Smith J.A. Turns in peptides and proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 1985;37:1–109. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hubbard S.J., Thornton J.M. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London; Bloomsbury, London: 1993. NACCESS. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rost B., Sander C. Conservation and prediction of solvent accessibility in protein families. Proteins. 1994;20:216–226. doi: 10.1002/prot.340200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen H., Zhou H.X. Prediction of solvent accessibility and sites of deleterious mutations from protein sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3193–3199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srinivasan R., Rose G.D. LINUS: a hierarchic procedure to predict the fold of a protein. Proteins. 1995;22:81–99. doi: 10.1002/prot.340220202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srinivasan R., Fleming P.J., Rose G.D. Ab initio protein folding using LINUS. In: Ludwig B., Michael L.J., editors. Methods Enzymol. Academic Press; 2004. pp. 48–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Urry D.W., Long M.M. Conformations of the repeat peptides of elastin in solution: an application of proton and carbon-13 magnetic resonance to the determination of polypeptide secondary structure. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1976;4:1–45. doi: 10.3109/10409237609102557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook W.J., Einspahr H., Bugg C.E. Crystal structure and conformation of the cyclic trimer of a repeat pentapeptide of elastin, cyclo-(L-valyl-L-prolylglycyl-L-valylglycyl)3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5502–5505. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fitzkee N.C., Fleming P.J., Rose G.D. The Protein Coil Library: a structural database of nonhelix, nonstrand fragments derived from the PDB. Proteins. 2005;58:852–854. doi: 10.1002/prot.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fitzkee N.C., Rose G.D. Reassessing random-coil statistics in unfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12497–12502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fitzkee N.C., Rose G.D. Sterics and solvation winnow accessible conformational space for unfolded proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;353:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fitzkee N.C., García-Moreno E B. Electrostatic effects in unfolded staphylococcal nuclease. Protein Sci. 2008;17:216–227. doi: 10.1110/ps.073081708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dominguez C., Boelens R., Bonvin A.M. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shrake A., Rupley J.A. Environment and exposure to solvent of protein atoms. Lysozyme and insulin. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;79:351–371. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brookes E., Demeler B., Rocco M. The implementation of SOMO (SOlution MOdeller) in the UltraScan analytical ultracentrifugation data analysis suite: enhanced capabilities allow the reliable hydrodynamic modeling of virtually any kind of biomacromolecule. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010;39:423–435. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ortega A., Amorós D., García de la Torre J. Prediction of hydrodynamic and other solution properties of rigid proteins from atomic- and residue-level models. Biophys. J. 2011;101:892–898. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harding S.E. Encyclopedia of Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. Frictional coefficient, ratio. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reichheld S.E., Muiznieks L.D., Sharpe S. Direct observation of structure and dynamics during phase separation of an elastomeric protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E4408–E4415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701877114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grzesiek S., Bax A. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:6291–6293. [Google Scholar]