Abstract

Social relations, although basic to human nature, health and well-being, have become increasingly complicated as a result of changing population demography and technology. In this essay, we provide a historical overview of social relations, especially as they affect older people. We briefly review the evolution of theory and measurement surrounding social relations as well as early empirical evidence. We consider how social relations have changed over time as well as continuity and change regarding basic characteristics of social relations. Of special interest is the emerging influence of technology on how people maintain contact, especially the changing ways people can use technology to increase, decrease, maintain, or avoid social relations. We consider both negative and positive aspects of these new technologies and their influence on health and well-being. Finally, we conclude that new and emerging technologies hold great promise for the future by overcoming traditional barriers to maintaining social contact, support exchange, and information acquisition. Nevertheless, we caution that these new technologies can have the dehumanizing effect of distance thus creating the potential for insensitivity and increased negativity. In sum, we are cautiously optimistic about the promise of technology to expand, but not replace, traditional forms of social contact.

Keywords: Health, Intergenerational, Social contact, Social support, Technology

Translational Significance

Incorporating technology into our study of social relations will be informative for our understanding of how communication modalities influence or are an expression of closeness and/or conflict. Further, technology has important potential for keeping social networks linked and for delivering potential interventions from telehealth to caregiving.

Social relations are a fundamental aspect of human life. This has been advocated early in the history of social science by luminaries such as Cooley (1902), Durkheim (1915), and Mead (1913), and continues to be of significance today as scholars document this point both theoretically and empirically, see Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Birditt (2014), for a review. Context also matters, in that the ways in which social relations evolve and influence well-being have been shown to vary across time and place (Ajrouch, Fuller, Akiyama & Antonucci, 2017; Fiori, Smith & Antonucci, 2007). At the same time, technological developments are fundamentally changing the ways in which we experience social relations, and may impact health and well-being accordingly. In this invited essay, we identify the convoy model as our guiding theoretical framework for understanding continuity and change in social relations. We consider how social relations have changed over time, specifically how technological advances engender new modes of contact for older adults. This is followed by a consideration of challenges facing the study of social relations, with particular attention to the need for theoretical and empirical assessments that take into account newly developing characteristics of our society. These include changes in the demography of the family and changes in migration patterns. We then elaborate on how new of experiencing social relations may have both positive and negative effects, thereby differentially influencing health and well-being. An important challenge to the field of social relations is to consider how to incorporate these developments into current and timely research.

The Convoy Model of Social Relations

The convoy model was developed to specify the scientific study of social relations by detailing the antecedent factors influencing social relations (personal and situational), identifying multiple dimensions of social relations, and illustrating how these factors influence health and well-being (Antonucci, 2001; Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). Individual characteristics such as age, gender, race, and religion illustrate the personal characteristics thought to influence social relations, whereas situational characteristics such as roles, norms, organizations, and communities were identified as important external factors influencing social relations. Multiple dimensions of social relations were specified to include convoy structure, support, and satisfaction or relationship quality. The tenets of the convoy model were built on key findings in the literature showing that social relations are an important part of the health and well-being of older people in the United States and around the globe.

Structure refers to characteristics of the people in one’s network such as size, composition, contact frequency, and geographic proximity. Size and composition are important in so far as larger, more diverse networks are associated with positive outcomes. Much evidence has accumulated to indicate that older people enjoy spending leisure time with friends and that these relationships are associated with positive well-being (Adams & Blieszner, 1989; Antonucci & Akiyama, 1995). On the other hand, older people also frequently report that they would turn to family, specifically spouse and children when in need. Cantor’s (1979) hierarchy of caregiving clearly designated the order of caregiving preference to be spouse/partner, child, other family, friend\neighbor, and formal caregiver.

A great deal of attention over the last century was given to the “decline of the family” as well as the decreased status of elders in our society. It was argued that older people were increasingly disrespected, alone, and isolated. Yet, classic studies challenged these notions with extensive, empirical investigations. It is now fairly well established, and convoy data continue to empirically support, that older people generally live quite close to and are in regular contact with their children (Ajrouch et al., 2017; Fiori, Antonucci & Akiyama, 2008; Shanas et al, 1968). Not only do older people receive help, support, and contributions from their children, they also provide these same types of assistance to their children. In fact, older people often provide more than they receive (Akiyama, Antonucci, & Campbell, 1997; Webster et al., 2012; Wiemers, Seltzer, Schoen, Hotz & Bianchi, 2016). In sum, social support structure includes various elements, all of which are included in the convoy model.

Support refers to the provision and receipt of support, such as aid, affect and affirmation. Lack of social support can have a significant negative impact on health and well-being. One of the most intriguing classic findings is that the single factor most likely to prevent nursing home placement is the report by the older person that they had a confidante, someone with whom they could share their intimate feelings (Lowenthal & Haven, 1968; this finding has been replicated around the world, e.g. in Australia by Giles, Glonek, Luszcz, & Andrews, 2007). Social support, and, in particular, protection from isolation and loneliness, are clearly important for the health and well-being of older people. The convoy model recognizes various support types, including instrumental and emotional support, as key predictors of health and well-being.

Satisfaction refers to one’s assessment of one’s social relations, sometimes referred to as adequacy or quality of relationships. It was thought that the existence of a relationship presupposed positive relationship quality and support. These assumptions were increasingly questioned as people began to note that while some families did evidence close, positive relationships, others might better be characterized as negative or ambivalent (both positive and negative) at best. Troll (1971) used the term residential propinquity to note that while many older people wanted to remain close to their family, they actually preferred not to live with them. She suggested that people recognized that it was easier to maintain positive relationships when some distance, privacy, and independence could be maintained. Family relations often include intergenerational relations. Bengtson and his colleagues expanded the family social relations literature by examining intrafamily intergenerational relations and introducing solidarity theory. According to this theory, positive features of adult child–parent ties include contact, emotional bonds, and support exchanges (Fingerman, Sechrist, & Birditt, 2013; Silverstein & Bengtson, 1997). In addition, once Bengtson and colleagues expanded this work to investigate the possibility of negativity in intergenerational relations (Silverstein, Parrott, Angelinni, & Cook, 2000), they found that in most families some level of conflict also existed, with younger people reporting more conflict than older people. Bengtson attributed this to differences in intergenerational stake, which referred to the fact that older people were more invested in family links to ensure their legacy, whereas younger people sought to establish independence and create their own legacy (Bengtson & Kuypers, 1971). Empirical evidence has accumulated supporting both these theoretical perspectives (Suitor, Sechrist, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2011). The convoy model ensures attention to the complexity of relationships quality.

Over the years, evidence has accumulated in support of the convoy model (Antonucci, 2001; Ajrouch et al., 2017). Fortunately, the model is designed to incorporate the study of newly emerging developments that might influence social relations. Technological advances, especially with regard to communication technology and social media, offer new ways for enabling older adults to establish social connectedness with family and friends (Czaja et al., 2017; Delello & McWhorter, 2017; Leist, 2013). Technology can also provide pathways for support in managing health conditions among older adults and those who provide care (Czaja, 2017). Though, as the convoy model posits, use and benefits of technology likely vary according to personal and situational characteristics, and will influence health in unique ways.

Incorporating Technological Developments Into the Study of Social Relations

The nature of social interaction has changed as technological advances have provided new methods of contact. Consider the evolution from in-person contact and letter writing to the telegraph and telephone and, most recently, to ever more individualized and electronic forms of contact such as cell phones, video calls (e.g., Skype, FaceTime), and social media (e.g., Facebook). We know very little about how different forms of communication influence social relations, health, and well-being.

To address the observation that social relations are now experienced in new ways because of technological developments, we recently analyzed a measure of contact frequency that distinguished in-person contact from telephone and electronic contact using the longitudinal Survey of Social Relations (Antonucci, Birditt & Webster, 2010). See Table 1 for a description of participant characteristics. We then examined the degree to which positive and negative relationship quality measured at Time 1, predicted adults’ frequency and use of different forms of communication 10 years later with members of their convoy, namely parents, spouse, child, and friend. We briefly report on our findings in the following paragraphs. For those who might doubt their use, we should note that older adults are increasingly using social media. While over 90% of young people are online and have cell phones, over half of adults age 65 and over are online and 78% own a cell phone (Anderson, 2015; Zickuhr & Madden, 2012).

Table 1.

Social Relations Study Wave 3 (Time 2) Sample Descriptives (N = 557)

| M (SD) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.8 (16.0) | |

| Education (years) | 14.2 (2.1) | |

| Female | 355 (63.7) | |

| Married/living with partner | 346 (62.1) | |

| Have children | 468 (84.0) |

Note. Includes nonindependent sample of respondents who completed interviews at both Time 1 and Time 2. M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Considering different contact modes, as expected, in-person contact was most frequent with spouse (see Table 2). Electronic communication was lowest with parents. Interestingly, telephone use was consistent across all relationships.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Contact Frequency With Network Members via Different Modesa

| In person | Telephone | Electronic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | |

| Mother | 3.30 (1.16) | 94 | 3.71 (1.16) | 94 | 2.27 (1.52) | 84 |

| Father | 3.31 (1.16) | 52 | 3.31 (1.16) | 52 | 1.98 (1.41) | 50 |

| Child | 3.53 (1.12) | 204 | 3.96 (1.00) | 205 | 3.47 (1.42) | 155 |

| Spouse | 4.88 (0.50) | 180 | 4.09 (1.35) | 179 | 3.39 (1.75) | 147 |

| Friend | 3.02 (1.17) | 187 | 3.62 (1.08) | 187 | 3.11 (1.56) | 150 |

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Contact frequency ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = daily.

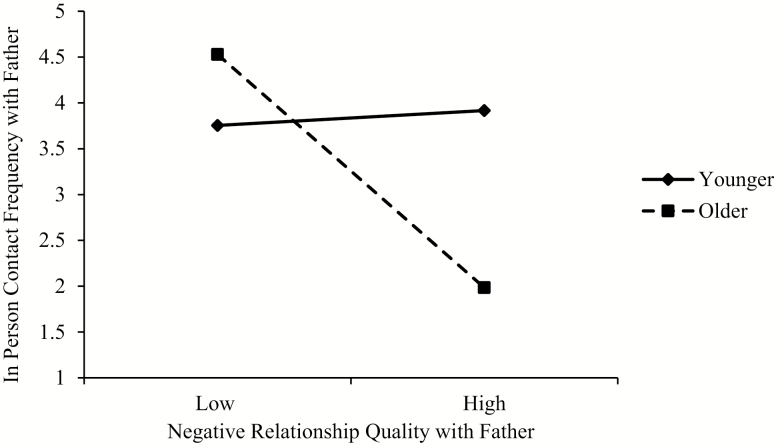

In many cases, links between relationship quality and contact differed between younger and older adults, depending on the mode of contact. Among older respondents, in-person contact frequency with fathers with whom respondents had a highly negative relationship was much lower than among those with a lower negative relationship quality (see Figure 1; all graphs plotted at 1 SD above and below the mean for relationship quality and age). On the other hand, there was little difference among younger respondents’ contact frequency across levels of negative relationship quality with father.

Figure 1.

Relationship quality by age interaction effect on in-person contact with father.

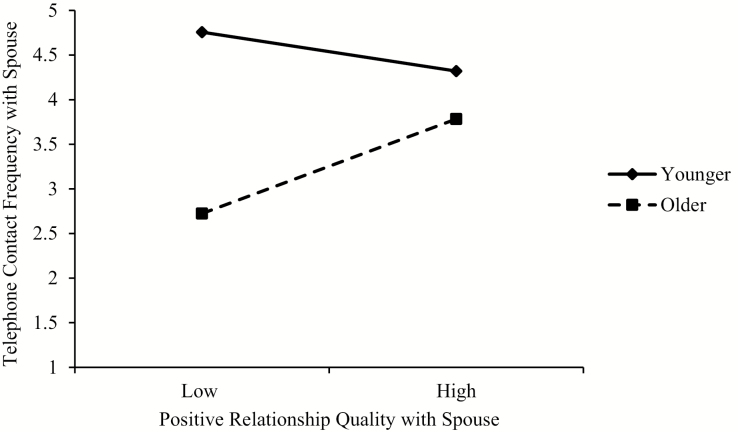

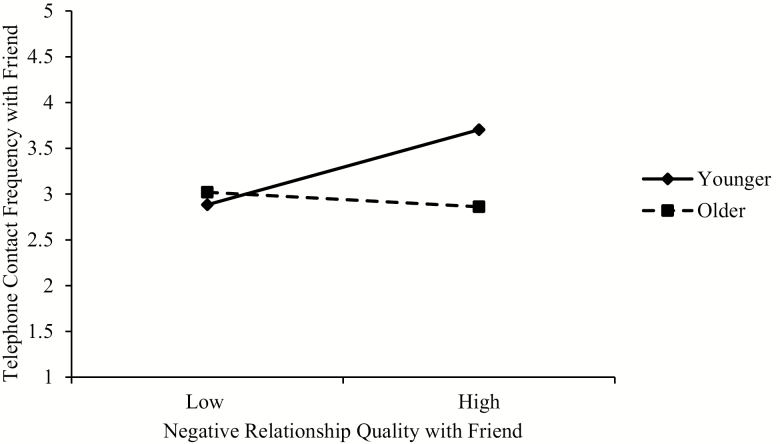

There was also an age × relationship quality effect on telephone contact with spouse indicating little difference among younger people, but older people with low spousal positive relationship quality reporting significantly less telephone contact with their spouse than those with a high spousal positive relationship quality (Figure 2). The findings with respect to negative relationship quality were somewhat but not completely parallel. Level of negativity in the relationship did not influence frequency of telephone contact with friends among older people but, interestingly, more negativity in the relationship was associated with more telephone contact with friends among younger people (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Relationship quality by age interaction effect on telephone contact with spouse.

Figure 3.

Relationship quality by age interaction effect on telephone contact with friend.

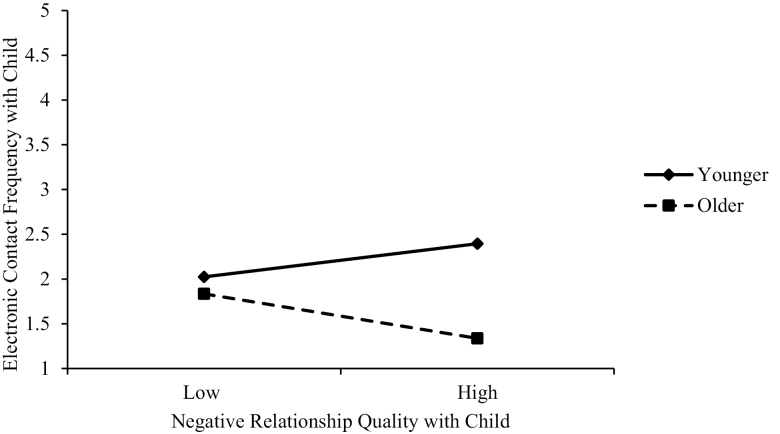

Finally, we examined the use of electronic forms of communication such as video chat, Skype, text, Facebook, and email. There were no effects of positive relationship quality across any of these forms of communication, although older people were less likely to use them than younger people. This age effect was also evident for negative relationship quality. Older people with high negativity in their relationship with their child were significantly less likely to communicate with them electronically than those with low negativity in their child relationship (Figure 4). On the other hand, once again there were no differences in electronic communications among young people regardless of the negativity of their relationship with child.

Figure 4.

Relationship quality by age interaction effect on electronic contact with child.

In sum, these findings show how new ways of experiencing social relations vary by age and relationship type. These findings do suggest some age differences but perhaps most importantly highlight the role of relationship quality to mode of communication. New ways of engaging in social relations are not evenly experienced across generations, and hence point to new areas for investigating how social relations influence well-being. Next, we present the ways in which new contact forms via technological developments inform the scientific study of social relations in the context of demographic shifts and health.

Population Demographic Shifts

Many technological advances have occurred within the context of broader demographic changes, including shifts in mortality, fertility, mobility, and marital patterns (Bianchi, 2014). Longer life spans provide older adults with more opportunities to build relationships with younger generations. Increased mobility and migration have led to less geographically proximate family networks, posing potential barriers to support exchanges and contact. Changes in marital patterns have resulted in increasing heterogeneity of family structures. Thus, older adults today are embedded within diverse and complex family structures that shape the type and quality of their social ties. It is important to consider these new aging family forms and functions when evaluating the role of technology in the establishment and maintenance of these social ties, and how the social needs of older adults are being met through technological advances in communication. We next discuss how these demographic shifts influence patterns of intergenerational and romantic relationships, the adaptation of immigrants, and the implications that technology has for these patterns.

Intergenerational Relations

Families are changing such that intergenerational ties, especially those across more than two generations, are becoming increasingly salient (Antonucci, Jackson, & Biggs, 2007; Bengtson, 2001; Swartz, 2009). Although older adults are less likely to adopt new technologies, they may be motivated to do so by intergenerational ties, e.g., to learn to use a smartphone or social media in order to maintain contact with children and grandchildren. A recent cross-national study demonstrated that countries with a higher prevalence of mobile phone subscriptions also had higher levels of maternal contact by adult children, particularly daughters (Gubernskaya & Treas, 2016).

Technology has the unique potential to influence grandparent–grandchild relationships due to younger generations’ faster adoption of new technologies. Although in-person communication continues to be the most frequent type of contact for grandparents, mobile phones, texting, and email are becoming increasingly popular as a means of staying in touch with grandchildren (Hurme, Westerback, & Quadrello, 2010; Quadrello et al., 2005). Given the increased mobility of families and the inverse relationship between geographic proximity and in-person contact, newer communication technologies provide a means by which grandparents can overcome barriers of distance to maintain meaningful ties with younger generations.

Increased levels of intergenerational contact via multiple media platforms, including texting and social networking sites, can have both positive and negative implications for the quality of relationships. Increased contact between older and younger generations could foster feelings of solidarity and closeness, leading to more positive evaluations of the relationship. On the other hand, higher levels of telephone and electronic contact could also promote more negative interactions and exchanges, especially when compared to in-person contact which may mute negativity because of the ability to perceive real-time reactions. Similarly, more technologically proficient individuals may feel frustrated with friends or relatives who struggle to communicate with newer technologies, eroding the quality of their relationship. More research is needed to identify the positive and negative implications of contact via newer technologies for intergenerational relationships, especially given the generational disparities in technology use (Fingerman & Birditt, 2011).

Immigrant Aging

New and varied ways to communicate across geographic distances have created a world of possibilities for immigrants. The advent of communication technologies such as Skype, WhatsApp, Viber, and FaceTime (among others), has made the ability to connect with close others who are geographically distant almost effortless. Moreover, smart phones are revolutionizing communication patterns, no longer restricting the ability to connect by having to be at a particular place. New technologies now facilitate connections between individuals wherever they are instead of individuals in specific locations. For older immigrants, these ways of having social relations may be a double-edged sword, as they facilitate relationships with those left behind, but may also make interactions in the host country more segregated. On the other hand, the Internet may simply serve as a buffer, much as ethnic enclaves do, facilitating adaptation and integration to the host society. We review recent findings in the following paragraphs.

Technology can be an outlet for immigrants who are socially isolated. For instance, among older immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Israel, social media became a resource that both reunited families and old friends living in various parts of the world, as well as helped to create new relationships (Khvorostianov, Elias, & Nimrod, 2012). This way of practicing social relations overcame major problems encountered by elderly immigrants—that of loneliness and social isolation. Khvorostianov and colleagues illustrate that such connections served as a source of joy and empowerment, facilitating transnational connections created through the Internet, ultimately supporting social integration. Similar trends have been identified among older Chinese immigrants living in New Zealand (Zhang, 2016).

For immigrants who leave their homeland at a young age, using information and communication technology (ICT) can, in fact, strengthen adaptation in the host country as one grows older. Hunter (2015) found that migrant workers from Africa living in France opted to remain in the host society after retirement given the ease with which they could connect with family back home as well as remain connected to attachments in France that were reinforced through smart phone technology. Evidence is accumulating to suggest that older immigrants’ social relations facilitated through ICT leads to stronger identities, and empowerment, overall enhancing quality of life. Yet, research of this sort is sparse, and generally occurs with small, nonrepresentative samples. The potential advantages and challenges that arise for immigrants through these new types of social relations is an area in need of further study.

Marital Patterns

A population trend that has widespread implications for how older adults use technology is the heterogeneity of marital statuses, including “gray divorce” (i.e., divorce after the age of 50; Brown & Lin, 2013) and never married older adults (Cooney & Dunne, 2001). The misconception that older singles are not interested in finding and maintaining romantic relationships is countered by increasing numbers of later life daters (Brown & Shinohara, 2013). The role that the Internet and social media play in establishing new romantic relationships presents a promising opportunity for research on how older adults use technology.

Although growing numbers of older adults turn to the Internet, including social media and dating websites, to find romantic partners, a surprising lack of attention has been paid regarding older adults’ use of technology to establish romantic connections. Online dating has become a popular means of finding romantic partners for people of all ages, including older adults. Some studies suggest that middle-aged and older adults may, in fact, be more likely than younger adults to use the Internet to meet potential partners (Stephure, Boon, Mackinnon, & Deveau, 2009; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). One advantage of online dating is that individuals’ partner preferences can be tailored and expectations can be explicitly stated. Older adults have been found to capitalize on this feature through the content of their online personal ads (Alterovitz & Mendelsohn, 2009; Davis & Fingerman, 2016; Wada, Mortenson, & Hurd Clarke, 2016).

In response to older adults’ adoption of the Internet in finding romantic partners, dating websites have made a more concerted effort to target this population. Popular dating websites boast large bases of older subscribers, whereas others are solely dedicated to serving adults aged 50 and older (e.g. OurTime.com). This is one example of how older adults are not simply consumers of new technology, but also influence the creation of new technology aimed to meet their social needs. Future research should consider the evolving bi-directionality of technology use by older individuals and their resulting influence on the development of new technology. Next, we consider how technology may impact social relations in the context of health.

Social Relations and Health

New technologies have been found to directly influence health due to the possibilities they generate to better connect with others. There is concern that the latest forms of contact and communication threaten community in the U.S. (Althaus & Tewksbury, 2000); yet, it appears that using the Internet is associated with higher levels of perceived support among older adults (Cody et al., 1999) and lower levels of isolation and loneliness (Cotten, Anderson & McCullough, 2013). Further, older adults are often motivated to use new technologies so that they may connect with others (Sims, Reed, & Carr, 2016). In sum, opportunities to enhance social relations through new technologies may initiate new ways to think about how social relations influence health and well-being.

New ways to create and sustain social relations may represent viable alternative sources for developing a sense of community in situations where mobility is limited or restricted. Research indicates that technological developments greatly expand communication options for older adults with mobility limitations, resulting in positive effects for well-being (Jaeger & Xie, 2009; Sims et al., 2016). Yet, the effects of communication technology are not necessarily always direct. For instance, Elliot and colleagues (2014) found that ill-health was a considerably weaker predictor of depressive symptoms for high ICT users than for non/limited users, but there was no direct effect of ICT on depressive symptoms. Furthermore, limitations in activities of daily living were a stronger predictor of depressive symptoms for high ICT users. Hence, the benefits of ICT for health are still not clear. Yet, the benefit of ICT-mediated social relations for health and well-being suggests multiple avenues to pursue for social support interventions that may address the challenges that older adults face with the onset of chronic illness. Technological innovations have also spawned various new forms of telehealth communications and treatment as well as social support interventions for their caregivers. We present examples of these potential opportunities next.

Social Support, Intervention, and Technology

Innovative uses of technology have been applied to create social support interventions that maximize good health and well-being. Use of the Internet has opened new avenues for enhancing social support for older adults, especially to address the threat of social isolation and loneliness. One such intervention is the Personal Reminder Information and Social Management (PRISM) system (Czaja et al., 2017). According to Czaja and colleagues, PRISM is a software application designed to support connectivity and resource access among older adults. In a randomized control trial, they showed that access to technology applications, especially email, Internet and games, facilitated social engagement, and provided an effective means of promoting social interactions and connections. Likewise, Delello and McWhorter (2017) showed in a mixed-method study among older adults living in a retirement community that iPads can be used to facilitate closer family relationships and greater overall connection to wider society. Moreover, both studies challenge myths that older adults avoid new technology. Instead, older adults can and will learn new skills to use technology successfully, even if they have never been exposed to it before.

Beyond the issue of social isolation, new communication technology creates unique ways for those with chronic disease to receive support that helps older adults meet the demands of managing illness. One promising mode involves interactive voice response technology (IVR). IVR provides an opportunity to use technology to schedule automated telephone assessment and self-care support calls (Heisler & Piette, 2005). In the case of diabetes, Heilser and Piette used IVR to facilitate connections between peers with the same disease. Findings showed that the technology facilitates an opportunity for reciprocity, where each peer receives and as well as provides support. Moreover, the support experience appears to generate increased self-efficacy, ultimately contributing to better management of diabetes. The IVR technology has also been extended to create the notion of CarePartners as a means to address the health and well-being of informal caregivers (Piette et al., 2015). Piette and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of mobile health support for heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. A CarePartner was identified by measuring the elements of closeness, support type, and quality of key individuals identified by the patient. That person then became the caregiver. The identified caregiver received weekly emails about their loved one’s status and suggestions for how to support self-management. In sum, the provision of informal support was facilitated by IVR and Internet technology. Technological innovations suggest several potential opportunities to leverage the benefits of social support for health and well-being.

Summary and Conclusion

New forms of communication have created unique challenges for understanding relationships. Electronic communication, such as Facebook, instant messaging, Snapchat, Skype, FaceTime, and have all created new opportunities to maintain contacts with close others. Cell phones and email have fundamentally changed how and how often people communicate. The reduced cost of these forms of contact has resulted in almost universal adaptation of some, if not all, of these tools of communication to maintain contact with friends and family. However, we know very little about the effect of these new forms of communication. On the plus side, increased communication can lead to less likelihood of isolation, with easy opportunity to share good news, seek advice about problems, manage health conditions, and generally enjoy exchanges with people we love (Czaja, 2017; Delello & McWhorter, 2017; Leist, 2013). But is there a minus side? It is also possible that people are losing the art of face-to-face contact, that people are more negative in less personal forms of communication, witness the rise in cyberbullying, because they do not see another’s reactions. Although it is recognized that these public forms of communication can be hurtful, little is currently being done to restrict such negativity. These are challenges that clearly must be addressed. Incorporating new ways of having social relations into theory, recognizing that the use and benefits of technology likely vary according to personal and situational characteristics, and that these new social relations will influence health in unique ways represent important future directions. The convoy model provides a helpful framework for thinking about the ways in which new technologies create new forms of social relations. It is quite clear that the advent and evolution of new communication technologies provide exciting and promising new directions for how we develop, use, and experience social relations.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health 1R01AG045423-01.

References

- Adams R. G. & Blieszner R (Eds.). (1989). Older adult friendship: Structure and process. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H., Antonucci T. C., & Campbell R (1997). Exchange and reciprocity among two generations of Japanese and American women. In Sokolovsky J. (Ed.), Cultural Context of aging: Worldwide perspectives (2nd ed, pp. 127–138). Westfort, CT: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alterovitz S. S.-R., & Mendelsohn G. A (2009). Partner preferences across the life span: Online dating by older adults. Psychology and Aging, 24, 513–517. doi:10.1037/a0015897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althaus S. L., & Tewksbury D (2000). Patterns of Internet and traditional news media use in a networked community. Political Communication, 17, 21–45. doi:10.1080/105846000198495 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. (2015). Technology Device Ownership: 2015 Retreived August 11, 2017, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/29/technology-device-ownership-2015/

- Antonucci T. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control. In Birren J., & Schaie K. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed). San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Ajrouch K. J., & Birditt K. S (2014). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, 54, 82–92. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., & Akiyama H (1995). Convoys of social relations: Family and friendships within a life span context. In Blieszner R. & Bedford V. H. (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the family (pp. 355–372). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Birditt K. S., & Webster N. J (2010). Social relations and mortality: A more nuanced approach. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 649–659. doi:10.1177/1359105310368189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Jackson J. S., & Biggs S (2007). Intergenerational relations: Theory, research, and policy. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 679–693. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00530.x [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch K. J., Fuller H. R., Akiyama H., & Antonucci T. C (2017). Convoys of social relations in cross-national context. The Gerontologist. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson V. L. (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x/full [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson V. L., & Kuypers J. A (1971). Generational difference and the “developmental stake.” Aging and Human Development, 2, 249–260. doi:10.2190/AG.2.4.b [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S. M. (2014). A demographic perspective on family change. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 6, 35–44. doi:10.1111/jftr.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., & Lin I.-F (2013). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., & Shinohara S. K (2013). Dating relationships in older adulthood: A national portrait susan. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 1194–1202. doi:10.1021/nl061786n.Core-Shell [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. H. (1979). Neighbors and friends: An overlooked resource in the informal support system. Research on Aging, 1, 434–463. doi:10.1177/016402757914002 [Google Scholar]

- Cody M. J., Dunn D., Hoppin S., & Wendt P (1999). Silver surfers: Training and evaluating Internet use among older adult learners. Communication Education, 48, 269–286. doi:10.1080/03634529909379178 [Google Scholar]

- Conney T. M., & Dunne K (2001). Intimate relationships in later life: Current realities, future prospects. Journal of Family Issues, 22, 838–858. doi:10.1177/019251301022007003 [Google Scholar]

- Cooley C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner’s. [Google Scholar]

- Cotten S. R., Anderson W. A., & McCullough B. M (2013). Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: Cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15, e39 doi:10.2196/jmir.2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S. J. (2017). The potential role of technology in supporting older adults. Public Policy and Aging Report, 27, 44–48. doi:10.1093/ppar/prx006 [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S. J., Boot W. R., Charness N., Rogers W. A., & Sharit J (2017). Improving social support for older adults through technology: Findings from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. The Gerontologist, gnw249 [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E. M., & Fingerman K. L (2016). Digital dating: Online profile content of older and younger adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 959–967. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delello J. A., & McWhorter R. R (2017). Reducing the digital divide: Connecting older adults to ipad technology. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 36, 3–28. doi:10.1177/0733464815589985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim É. (1915). Elementary forms of the religious life. New York, Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot A. J., Mooney C. J., Douthit K. Z., & Lynch M. F (2014). Predictors of older adults’ technology use and its relationship to depressive symptoms and well-being. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 667–677. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbt109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L., & Birditt K. S (2011). Relationships between adults and their aging parents. In Schaie K. W., & Willis S. L. (Eds.), Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (7th ed, pp. 219–232). Elsevier Inc; 10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00014-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L., Sechrist J., & Birditt K (2013). Changing views on intergenerational ties. Gerontology, 59, 64–70. doi:10.1159/000342211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori K. L., Antonucci T. C., & Akiyama H (2008). Profiles of social relations among older adults: A cross-cultural approach. Ageing and Society, 28, 203–231. doi:10.1017/S0144686X07006472 [Google Scholar]

- Fiori K. L., Smith J., & Antonucci T. C (2007). Social network types among older adults: A multidimensional approach. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, P322–P330. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.6.P322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles L. C., Glonek G. F., Luszcz M. A., & Andrews G. R (2007). Do social networks affect the use of residential aged care among older Australians?BMC Geriatrics, 7, 24 doi:10.1186/1471-2318-7-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubernskaya Z., & Treas J (2016). Call home? Mobile phones and contacts with mother in 24 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1237–1249. doi:10.1111/jomf.12342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M. & Piette J. D (2005). “I help you, and you help me”: facilitated telephone peer support among patients with diabetes. The Diabetes Educator, 31, 869–879. doi:10.1177/0145721705283247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A. (2015). Empowering or impeding return migration? ICT, mobile phones, and older migrants’ communications with home. Global Networks, 15, 485–502. doi:10.1111/glob.12091 [Google Scholar]

- Hurme H., Westerback S., & Quadrello T (2010). Traditional and new forms of contact between grandparents and grandchildren. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 8, 264–280. doi:10.1080/15350770.2010.498739 [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger P. T., & Xie B (2009). Developing online community accessibility guidelines for persons with disabilities and older adults. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 20, 55–63. doi:10.1177/1044207308325997 [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L., & Antonucci T. C (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles and social support. In Baltes P. B. & Brim O. G. (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khvorostianov N., Elias N., & Nimrod G (2012). ‘Without it I am nothing’: The internet in the lives of older immigrants. New Media and Society, 14, 583–599. doi:10.1177/1461444811421599 [Google Scholar]

- Leist A. K. (2013). Social media use of older adults: A mini-review. Gerontology, 59, 378–384. doi:10.1159/000346818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal M. F. & Haven C (1968). Interaction and adaptation: Intimacy as a critical variable. American Sociological Review, 33, 20–30. doi:10.2307/2092237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead G. H. (1913). The social self. Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 10, 374–380. doi:10.2307/2012910 [Google Scholar]

- Piette J. D., Striplin D., Marinec N., Chen J., & Aikens J. E (2015). A randomized trial of mobile health support for heart failure patients and their informal caregivers: Impacts on caregiver-reported outcomes. Medical Care, 53, 692–699. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadrello T., Hurme H., Menzinger J., Smith P. K., Veisson M., Vidal S., & Westerback S (2005). Grandparents use of new communication technologies in a European perspective. European Journal of Ageing, 2, 200–207. doi:10.1007/s10433-005-0004-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanas E., Townsend P., Wedderburn D., Friis H., Milhoj P., & Stehouwer J (Eds.) (1968). Old people in three industrial societies. New York: Atherton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M., & Bengtson V. L (1997). Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child-parent relationships in American families. American Journal of Sociology, 103, 429–460. doi:10.1086/231213 [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M., Parrott T., Angelinni J. J., & Cook F. L (2000). Solidarity and tension between age groups in the United States: Challenge for an aging America in the 21st century. International Journal of Social Welfare, 9, 270–284. doi:10.1111/1468-2397.00139 [Google Scholar]

- Sims T., Reed A. E., & Carr D. C (2016). Information and communication technology use is related to higher well-being among the oldest-old. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , gbw130. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephure R. J., Boon S. D., Mackinnon S. L., & Deveau V. L (2009). Internet initiated relationships: Associations between age and involvement in online dating. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14, 658–681. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01457.x [Google Scholar]

- Suitor J. J., Sechrist J., Gilligan M., & Pillemer K (2011). Intergenerational relations in later-life families. In Settersten R., and Angel J. (Eds.) Handbook of Sociology of Aging (pp. 161–178). New York: Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4419-7374-0_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz T. T. (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 191–212. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615 [Google Scholar]

- Troll L. E. (1971)The family of later life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 33, 263–290. doi:10.2307/349414 [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P. M., & Peter J (2007). Who visits online dating sites? Exploring some characteristics of online daters. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 10, 849–852. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.9941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada M., Mortenson W. B., & Hurd Clarke L (2016). Older adults’ online dating profiles and successful aging. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 35, 479–490. doi:10.1017/S0714980816000507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster N. J., Antonucci T. C., Yoon C., McCullough W. R., Fin D. N., & Hartsell D. L (2012). Older adults as consumers: An examination of differences by birth cohort. In Preston S., Kringelback M., & Knutson B. (Eds.) Interdisciplinary Science of Consumption (pp. 281–298). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemers E. E., Seltzer J. A., Schoen R. F., Hotz V. J. & Bianchi S. M (2016). The Generational Structure of U.S. Families and Their Intergenerational Transfers. PSC Research Report No. 16–867. 7 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UCLA CCPR Population Working Papers . Retrieved from http://papers.ccpr.ucla.edu/index.php/pwp/article/view/PWP-CCPR-2016-036 10.1186/s40711-016-0045-y. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. (2016). Aging in cyberspace: Internet use and quality of life of older Chinese migrants. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 3, 26. doi:10.1186/s40711-016-0045-y [Google Scholar]

- Zickuhr K. & Madden M (2012). Older adults and Internet use. For the first time, half of adults aged 65 and older are online Retrieved from http://pewinter- net.org/Reports/2012/Older-adults-and-in- ternet-use.aspx