Abstract

Background:

There is an assumption that sexual health research has great influence on the quality of human life through elevating sexual health standards, and their results will eliminate the burden of sexual health challenges on family relationships. The aim of this study was to review ethical considerations in sexual health research.

Materials and Methods:

This narrative review was conducted between January 1990 and December 2017 based on the five-step approach of York University. The keywords used to search for the studies included ethical issues, research, sexual health, reproductive health, and sensitive topics. The language of the literatures was English and the search process was performed on PubMed, Elsevier, Ovid, Springer, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, SAGE Publishing, ProQuest, WHO website, Kinsey Confidential, and Worldsexology.

Results:

After assessing the quality and eligibility of 94 articles, 13 were selected. The results of the present study showed that the most important ethical considerations were protecting the confidentiality and privacy of participants, obtaining informed consent, and paying attention to vulnerable people.

Conclusions:

The review of literature exhibited several considerations that sexual health researchers are faced with. In order to manage these considerations, the researcher should have sufficient understanding of them. The important matter is that strategies to manage these challenges should be completely rational and practical according to each context. These strategies can also be applied in other societies with great similarities in their context.

Keywords: Ethics, research, sexual health

Introduction

Ethical considerations in research refer to a set of rules and guidelines that should be considered in order to avoid possible damage to participants and researchers.[1,2,3] There is no general description of the characteristics of a sensitive research, except for topics that have been accepted as sensitive as a result of experiences. Some examples of sensitive topics include sexual behaviors, drug abuse, topics that arouse emotions, and other topics tagged as a taboo.[4,5] The level of sensitivity can vary according to some characteristics of participants, such as age (for example, adolescents under 15 years of age or elderly people), gender identity (for example, homosexuals), and mental health retardation.[5] Some other topics, such as abuse and violence, are also considered sensitive as they can remind participants, who have been victims of past traumatic memories. For example, in some cases such as sexual violence, ethical complexities emerge because using methods such as in-depth interviews and questioning can arouse painful emotions and memories in victims.[6]

Researchers have different views on sensitivity of sexual topics. Many claim that sexual topics are not more sensitive than other research areas,[4,7] whereas others believe that these studies are highly sensitive.[8,9] It should be noted that sensitivity affects all details of research, from designing the approach to implementing and publishing the results.[10]

In countries with a traditional and religious context such as Iran, some of the traditional beliefs and social structures make it difficult to conduct sexual health and sensitive research.[11] Studies on sexual health and sensitive topics become important in the case of the widespread occurrence of some high-risk sexual conditions, such as HIV, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion due to some risk factors such as very young age at the time of first sexual relationship, multiple sex partners, extramarital relationship, and above all, the lack of any education and information provision especially among adolescents. The common language of sex in Iran is the language of silence, because sex and related issues are considered a taboo and talking about them freely in most settings is forbidden.[11] Therefore, this study was conducted to identify ethical considerations in research related to sexual health and sensitive research.

Materials and Methods

This narrative review study was conducted in 2017 to determine the ethical considerations in research related to sexual health and sensitive topics (such as, trafficked women, unwanted pregnancy and illegal abortion especially in adolescents, sexual violence, etc.) based on the five-step approach of York University. This approach includes development of the research question, identification of relevant studies, assessment of the quality of the studies, summarization of the evidence, and analysis and synthesis of information.[12,13]

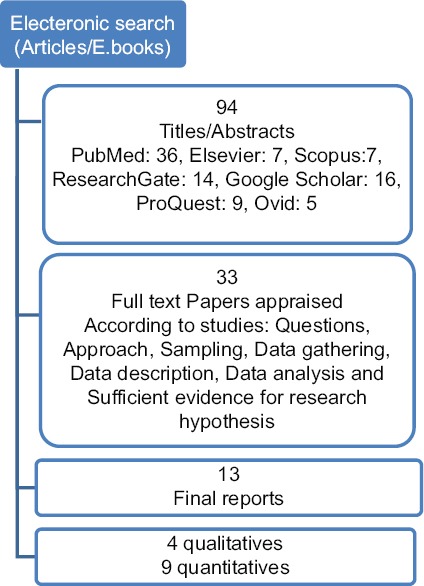

The databases used included PubMed, Elsevier, Ovid, Springer, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, SAGE Publishing, and ProQuest. Moreover, websites, including who.org, kinseyconfidential.org, and worldsexology.org, were searched to find relevant studies using keywords such as “Ethical issues, Research, Sexual Health, Reproductive health, and Sensitive Topics”. In the first stage, the keywords were searched separately, and then, they were combined with “and” or “or” to make some new keywords or phrases. The search process was conducted on articles published from January 1990 until December 2017. At first, 94 texts, including E-books and articles were obtained; 36 articles gained from PubMed, 7 from Elsevier, 7 from Scopus, 14 from ResearchGate, 16 from Google Scholar, 9 from ProQuest, and 5 from Ovid. After inspecting the inclusion criteria, including year of publication, language, and consisting of clear and precise description of ethical considerations related to the research question and suitable method of data gathering and analysis, 33 articles were selected. Finally, 13 articles were identified as eligible for the study after the thorough review of the texts. The quality of the selected articles was assessed based on a checklist consisting of the standard components of qualitative, descriptive, and review studies. The most important criteria were: Has the question of the study been developed clearly?; Is the approach of the study appropriate for answering the question of the study?; Has the background of the study been described well?; Has the sampling procedure of the study been fully described?; Has the data collection method been described well?; and Is the data analysis method appropriate for this study?.[14] In addition, to ensure the reliability of the selected studies, each article was reviewed by at least two members of the research team. Finally, concepts in different categories were separately identified and studied; there were no considerable differences among the opinions of the members. Then, all the content was analyzed and categorized, and ethical challenges were fully described. The process of article selection is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of finding resources

Ethical considerations

Research ethics confirmation was received from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Results

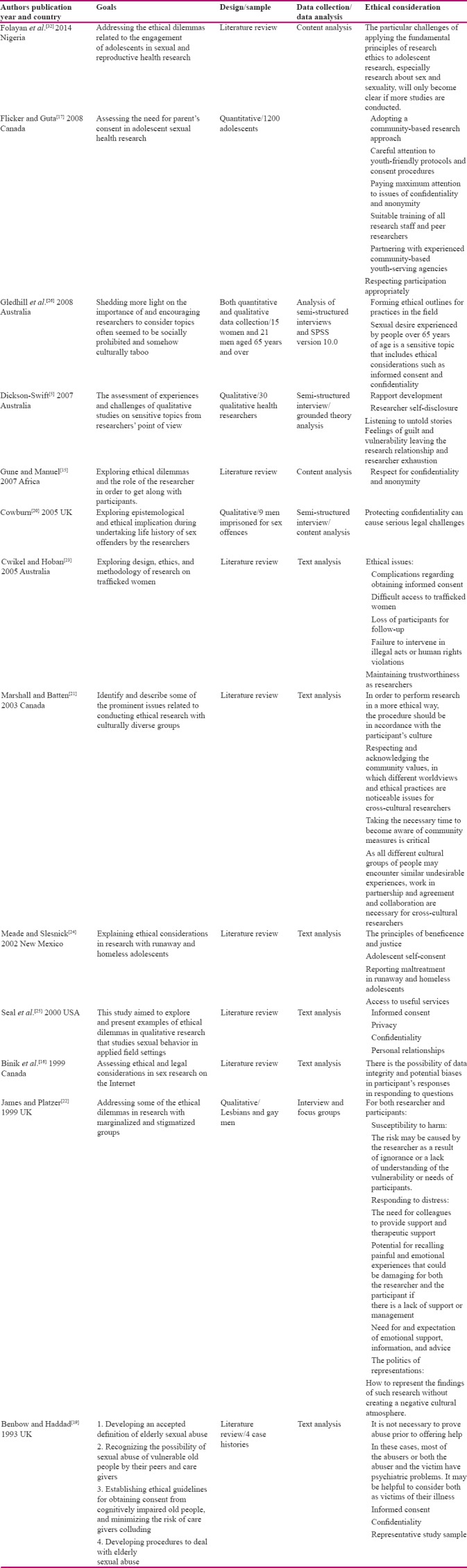

In this study, 13 studies were reviewed, which were conducted in 7 different countries including Canada, Australia, Britain (3 articles each), Nigeria, Africa, Mexico, and America (1 article each). In the review, unfortunately, no Iranian or even Persian articles were found in this regard. In total, 1,275 individuals have participated in quantitative and qualitative studies. The data collection methods used in these articles were different; individual and group interviews with purposive sampling in qualitative studies and convenience sampling in quantitative studies, examining a case report, and review of articles.

The results showed some similar and common ethical considerations related to sexual health and sensitive research in all of the reviewed studies. In 2007, Gune and Manuel stated that performing any research on sexual issues can cause embarrassment in participants, because sexual health research often interferes with individual's privacy, and the ethical concepts of studies as well as the publication of their findings may cause many problems. This study sheds more light on the importance of the confidentiality and anonymity of participants and results.[15]

In 1999, Binik et al. in Canada studied ethical issues regarding conducting sexual research on the Internet.[16] They stated that the Internet provides the virtual space for conducting innovative research in sexual topics, but this new world is associated with new ethical complications like ethical issues related to participants' registration in the research, informed consent, and collecting and storing data. Special methods and caution are required in order to collect information from children in order to protect privacy and preserve and record sensitive information. Finally, the researchers stated that the research related to sexual issues on the Internet is associated with a few risks; they considered common ethical standards to be sufficient for ordinary research in this field. It seems that risks on the Internet are not so extreme as to require the use of strict standards in this respect.[16]

In 2008, Flicker and Guta conducted a study to evaluate the necessity of obtaining parental consent for participation of adolescents in these types of studies.[17] Their hypothesis was that the process of parental intervention may have no place in this type of research because it is in contrast to the principal of participants' autonomy.[17]

In a qualitative research conducted by Dickson-Swift in 2007, the ethical considerations in studies with sensitive topics included communication between researchers and participants, relationship with isolated person, the creation of a sense of guilt in the researcher, vulnerability due to leaving the research relationship, and fatigue caused by the study.[18]

In a review article, Benbow and Haddad examined the ethical considerations in research on elderly patients with dementia, who were sexually abused, in 1993.[19] The results showed that in most cases the rapist had a history of psychological disorders, which indicates that both rapist and rape victim can be victims of their psychiatric disease. The most important challenges in this type of study have been the problem of connecting with participants and the perilous situation of the study that could endanger the researcher due to the presence of both offenders and victims.[19] Cowburn in 2005 evaluated the ethical complexities in studies where the participants were sex offenders.[20] In interviewing this group of people, the principle of confidentiality should be repeated by the investigator at the start of each new section of the study. The result indicated that observing the principle of confidentiality could legally cause serious challenges, especially when the researcher is informed of an unpleasant imminent incident.[20]

In a study conducted by Marshall and Batten in 2003 on groups with different cultures, the results showed that the research process must be based on the culture of each group of participants, respect for the values of each community, and devoting enough time to familiarization with the culture of each group of participants.[21] In 1999, James and Platzer conducted a study to evaluate the ethical considerations of research on minority groups, and the marginalized and stigmatized population. The results indicated some challenges such as the vulnerability of researchers and participants, the need for partnership of the researcher and his/her coworkers to support him/her in case of stress, the participants' potential for remembering emotionally painful experiences, using appropriate policies to deliver the results of these studies without negative influence on the cultural atmosphere of the community.[22]

Cwikel and Hoban, in another study in 2005, explored the ethical issues in studies on trafficked women.[23] They pointed out that the ethical considerations in research on this group in the most important cases included the complexities associated with obtaining informed consent, legal punishment for researchers who get involved in illegal actions for the benefits of their study, and protection of the rights of vulnerable participants by the researcher.[23] The results of the study on ethical considerations of research on runaway and homeless young people as vulnerable populations, which was performed by Meade and Slesnick in 2002, revealed that maintaining beneficence and justice, ensuring the autonomy of the teenager, obtaining informed consent from the teenager, reporting any abuse regarding runaway and homeless teenagers, and providing access to useful services as the most important ethical necessities.[24]

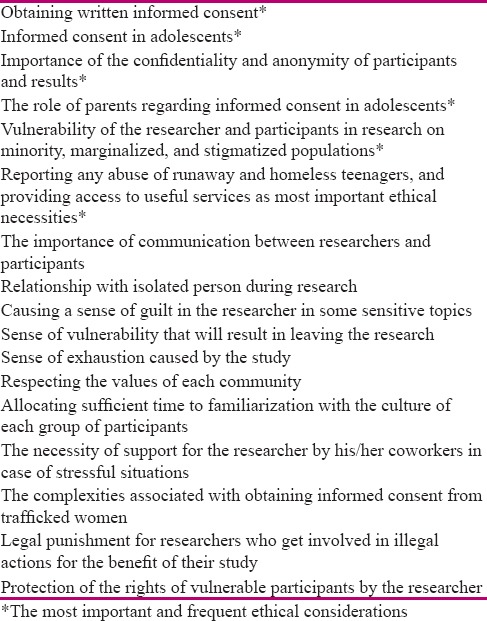

In a study by Seal et al. in 2000 on qualitative studies with the subject of sexual health, the most important ethical considerations included obtaining informed consent, maintaining privacy and confidentiality, and observing the principles of establishing communication in such qualitative studies.[25] Gledhill et al. in 2008 studied the culturally taboo and forbidden topics in various communities; indeed they wanted to disclose the importance of sex research as a socially prohibited and culturally taboo topic. Furthermore, they indicated obtaining informed written consent and confidentiality as the most important ethical considerations.[26] A comparison of the characteristic of all 13 studies is presented in Table 1. In Table 2, almost all ethical considerations found during this study have been listed.

Table 1.

Outline of the studies included in the review

Table 2.

Ethical considerations and challenges in sexual and sensitive research

Discussion

Based on the results of the study, the most important attained ethical considerations were protecting the confidentiality and privacy of participants, various aspects of informed consent, informed consent in vulnerable participants (particularly adolescents), the necessity of standard ethical protocols for sexual health and sensitive research, and ethical issues in publishing sexual health or sensitive research results. The summary of results is provided in Table 2.

Confidentiality and privacy

Among the 13 reviewed studies, 6 indicated that, based on the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, all precautions to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants' personal information should be considered.[19] The violation of the confidentiality and privacy of participants are circumstances in which they lose their control over personal information that has been provided during the study.[26] The most important part of these concerns is related to preserving the dignity and individual control of participants and establishing rapport with them in order to guarantee the validity and integrity of the study. These concerns are particularly among vulnerable groups such as young people, drug abusers, prostitutes, people with dementia, etc. The concerns of scientists and researchers about ethical standards have guided them to feel the necessity for creating ethical guidelines and solutions in order to protect the participants from risks and maintaining their privacy by establishing confidentiality. In addition, scientists are looking for guidelines that can protect novice researchers from potentially dangerous conditions.[27] Regarding vulnerable people, although some issues in studies are usual, there are some cases that should be considered as uniquely and independently sensitive issues. For example, observing privacy in studies on adolescents, especially in dealing with high-risk behaviors, can be performed with the conditional or unconditional consent of the adolescent.[28] The principle of privacy is not only a topic in the context of ethics, but also is an individual right regarding privacy and freedom from danger.[29] Preserving privacy and confidentiality is one of the main concerns of adolescents who take part in research. They are normally and potentially prone to self-harm or abuse by relatives. For example, in case of domestic violence, if the adolescent feels that there is the risk of the offender becoming aware of the presented information, he/she will be frightened and this may result in self-censorship. In addition, there is the risk of each member of the research team disclosing information related to the adolescent participants and the results of the research.[30]

Parental intervention and interference mainly with adolescents above 15–18 years of age regarding the research atmosphere, especially in sensitive topics, may result in a kind of self-censorship by the adolescents. The confusion of the adolescents can finally result in silence, because of the fear of exposing their private matters; however, in sexual health research, the accuracy of the adolescents' speech is crucial.[17]

There are some exceptions related to preserving privacy during research. If researchers understand that there is some risky behavior or condition that can potentially endanger the adolescent's health, they should break their silence and inform the parents or law. Please notice that in any situation related to risky behavior, the health and well-being of children and adolescents are more important than confidentiality.[31]

Informed consent

The participation of people qualified to provide informed consent as study subjects or participants in health and medical studies must be voluntary. An informed consent in research can only be obtained when participants are fully informed of the objectives, methods, sources of information, the possibility of any conflict of interest, organizational affiliation of the researcher, potential benefits and risks of the study, the requirements after the study, other aspects related to the study, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time, freely, and without any risk of retaliation.[19] Obtaining informed consent in cases such as vulnerable population, such as adolescents, has special importance and it may challenge researchers. In 2014, Folayan et al. stated that deciding on the adequacy of informed consent in adolescents was mostly based on birth certificate age rather than on a direct assessment of adolescents' capacity to understand the issues and ability to offer informed consent for participation in the study.[32] Moreover, Folayan et al. are of the opinion that the participation of adolescents in research is compulsory, and therefore, adolescents do not have a comprehensive understanding of damage related to participating in those studies.[32] Based on the Islamic Republic of Iran research ethical guide on vulnerable people, children and adolescents are among vulnerable groups, and regarding the ability to give informed consent, children are categorized into three groups. The first group consists of children of less than 7 years of age, in which written informed consent should be obtained from both parents, or if they are absent, from their legal guardian, especially in clinical research. The second group consists of 7- to 15-year-old children, in which written informed consent should be obtained from the children's legal guardians and as well as the children according to their understanding and cognitive power. Children of above 15 years of age constitute the third group, in which written informed consent should be obtained from both the legal guardian and child.[33] In addition, participants of over 18 years of age are authorized to participate in research without parental consent or even awareness.[33]

Vulnerable people

Sexual health and sensitive research on vulnerable people (adolescents, sexual minorities, prostitutes, sexual violence victims, etc.) should be conducted with the maximum protection specific to each group. Studies on such participants are justified only in the case of paying attention to their special health needs and only when it is not possible to perform the study on ordinary people. In addition, these people should be aware of the results of the research and types of interventions. Moreover, there should be sufficient rational support for all the interventions performed and actions taken in these kinds of research.[19] For example, careful attention and special adolescent-friendly protocols are the basic requirements for research on this age group. The Convention on the Rights of the Child includes the most basic human rights for children.[31] This protocol has been the most widely accepted human rights document in history and includes 54 articles and 2 optional protocols with 4 basic principles. These principles include no child should suffer from discrimination; when a decision is made regarding children, their highest interests must be taken into account, children should have the right to live and develop,[10] children have the right to express their ideas freely, and these ideas should be considered in all issues related to them.[34] In order to observe the rights of adolescents under the form of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, although these models have been defined as the standards in the world, a more specialized protocol should be developed in each context and in each research according to the study objectives and characteristics of the target group, using the four mentioned principles.

During work with vulnerable people, there is the chance of evoking terrifying memories in the participants, for example, in a victim of sexual violence. In these cases, the researcher or interviewer should be equipped with consulting skills and in the least time begin counseling the participant to minimize the maleficent effects of the research.[18]

Standard ethical protocols for sexual and sensitive research

Research with human subjects must be conducted based on scientific and generally accepted principles. The design and method of such studies should be clearly explained and justifiable based on a research protocol. The research protocol should include information such as the research funding, institutional affiliations of the researcher, potential conflicts of interest, and motivation of the participants, information on the rules of the treatment or research, and the ways to compensate possible losses due to research.[19] For example, if the data gathering method in a sensitive study is through the use of the Internet, researchers should be aware of possible threats that place data and information at risk as well as potential biases of participants in responding to questions through a computer and report them clearly.[16] There are several phenomena that are considered as sensitive according to specific cultural and social contexts. For example, topics with a dominant private nature, stressful topics, and topics related to death, fears of stigma, and sexual problems that can evoke the feelings of people are considered sensitive. The experiences and review of studies have revealed that not only are the participants exposed to the influence of the sensitive nature of the study process, but also the researchers are susceptible to the effects of these studies. Researchers and participants involved in the study, observers, and readers of published results could also be considered as susceptible. In order to protect the physical and psychological health of all people, developing the protocols and guidelines at the beginning of each study is essential in order to identify and reduce risks or loss during the research.[35] Clear and precise protocol and strategies to minimize the potential risk and loss during the research should be included in the proposed design of research with sensitive topics. They should also be provided for the ethics committee in order to prevent any misconception and decrease the risk of the rejection of the proposed topic. In studies conducted through interview or when interview is a part of them, the way to reduce the threats from the first step of meeting the interviewee, arranging interviews, protecting the physical and psychological health of the interviewer and interviewee, predicting the approach to end the interview, and the final report should be included in the proposed protocol. Another benefit of a standard protocol is to prevent the creation of unrealistic or unnecessary obstacles especially in sensitive research by the ethics committee.[36]

Disseminating the result of the studies

Researchers, authors, sponsors, editors, and publishers are required to observe all ethical issues related to the publication of the research results. Researchers are responsible for human subjects and the accuracy of the reports. When publishing the results, the source of funding, institutional affiliations, and any conflicts of interest must be clearly expressed. If there is any conflict between regional ethical guidelines and principles and the international statements of ethical principles, such as the Helsinki statement, the results should not be accepted for publishing.[19] Sociocultural and religious sensitivity are some of the most important specialized characteristics in most studies with sensitive topics and on sexual health, which mainly induce the researcher to use unclear words and concepts at the stage of publishing the results. At the end of this spectrum, sometimes we are faced with self-censorship by researchers, due to the consequences of results publication or the absence of project approval by research ethics committees that, in turn, causes uncertainty regarding the accuracy of the findings. Another form of self-censorship is created by the participants often due to the private nature of data and feeling of shame due to the taboo nature of the information. Finally, in some cases, in order to prevent anxiety, tension, and disturbance in the atmosphere of the community, the whole or a part of the results of some studies with sensitive topics are provided merely to groups of decision-makers, officials, and related experts, and publishing the results for the community is prohibited.

However, this topic is one of the priorities of our society in order to promote sexual science. A limited number of studies have been conducted on sexual issues in Iran, which caused limitation in results generalization and native suggestions. The importance of sexual health and issues around the world and Iran is due to several causes including high-risk sexual behaviors, for example, the onset of high-risk sexual relationships at a young age.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, ethical considerations in sexual health and many other sensitive topics have great similarities in terms of moral principles and standards. It should be noted that these common ethical principles in biomedical studies, based on the special nature of sexual health and sensitive topic research, not only can be interpreted in one study differently from another study but also are affected differently by the dominant culture of each society.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicting Interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful for the support provided by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in approving this project with the number 393866 and the National Committee of Ethics in Research of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education for scientific grant. Also, we appreciate all the people who contributed in this research kindly.

References

- 1.Sharifirad GF. Scientific misconduct: Self-plagiarism [PERSIAN] J Health Syst Res. 2012;8:922–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabei SZ, Mahmoodian F. Ethics in Research [PERSIAN] Ethics Sci Technol. 2007;2:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farhood D. Academic Ethics in Education and Research [PERSIAN] Ethics Sci Technol 2010. 2011;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noland CM. Institutional barriers to research on sensitive topics: Case of sex communication research among university students. J Res Prac. 2012;8:2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickson-Swift V. Doing sensitive research: What challenges do qualitative researchers face? Qual Res. 2007;7:327–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draucker CB. The emotional impact of sexual violence research on participants. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1999;13:161–9. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(99)80002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford K, Norris A. Methodological considerations for survey research on sexual behavior: Urban African American and Hispanic youth. J Sex Res. 1991;28:539–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford M, Popp D. Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. J Sex Res. 2003;40:13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey JH, Wenzel A, Sprecher S. The Handbook of Sexuality in Close Relationships. New York: 2004. pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCusker J, Stoddard AM, Mayer KH, Zapka J, Morrison C, Saltzman SP. Effects of HIV antibody test knowledge on subsequent sexual behaviors in a cohort of homosexually active men. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:462–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmani A, Merghati-Khoei E, Moghaddam-Banaem L, Zarei F, Montazeri A, Hajizadeh E. Sexuality research in Iran: A focus on methodological and ethical considerations. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:118–21. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahriari M, Mohammadi E, Abbaszadeh A, Bahrami M. Nursing ethical values and definitions: A literature review. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munro SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gune E, Manuel S. African Sexualities: A reader. Oxford: Pambazuka; 2011. Doing research on sexuality in Africa: Ethical dilemmas and the positioning of the researcher. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binik YM, Mah K, Kiesler S. Ethical issues in conducting sex research on the Internet. J Sex Res. 1999;36:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flicker S, Guta A. Ethical approaches to adolescent participation in sexual health research. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyle A, Wright C. Using the counselling interview to collect research data on sensitive topics. J Health Psychol. 1996;1:431–40. doi: 10.1177/135910539600100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benbow SM, Haddad PM. Sexual abuse of the elderly mentally ill. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:803–7. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.816.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowburn M. Confidentiality and public protection: Ethical dilemmas in qualitative research with adult male sex offenders. J Sexual Aggression. 2005;11:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall A, Batten S. Ethical issues in cross-cultural research. Connections. 2003;3:139–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.James T, Platzer H. Ethical considerations in qualitative research with vulnerable groups: Exploring lesbians' and gay men's experiences of health care–A personal perspective. Nurs Ethics. 1999;6:73–81. doi: 10.1177/096973309900600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cwikel J, Hoban E. Contentious issues in research on trafficked women working in the sex industry: Study design, ethics, and methodology. J Sex Res. 2005;42:306–16. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meade MA, Slesnick N. Ethical considerations for research and treatment with runaway and homeless adolescents. J Psychol. 2002;136:449–63. doi: 10.1080/00223980209604171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seal DW, Bloom FR, Somlai AM. Dilemmas in conducting qualitative sex research in applied field settings. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:10–23. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gledhill SE, Abbey JA, Schweitzer R. Sampling methods: Methodological issues involved in the recruitment of older people into a study of sexuality. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;26:84–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderpool HY. The ethics of research involving human subjects: Facing the 21st century. 1996 DOI :10.1056/NEJM199703203361219. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulte P, Sweeney MH. Ethical considerations, confidentiality issues, rights of human subjects, and uses of monitoring data in research and regulation. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:69. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Association AP. American Psychiatric Association The Principles of Medical Ethics. 23th edition. 2013. Available at online: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9780890 426760.

- 30.Mack R, Giarelli E, Bernhardt BA. The adolescent research participant: Strategies for productive and ethical interviewing. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24:448–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rae WA, Sullivan JR, Razo NP, George CA, Ramirez E. Adolescent health risk behavior: When do pediatric psychologists break confidentiality? J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:541–9. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folayan MO, Haire B, Harrison A, Odetoyingbo M, Fatusi O, Brown B. Ethical issues in adolescents' sexual and reproductive health research in Nigeria. Dev World Bioeth. 2015;15:191–8. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lothen-Kline C, Howard DE, Hamburger EK, Worrell KD, Boekeloo BO. Truth and consequences: Ethics, confidentiality, and disclosure in adolescent longitudinal prevention research. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:385–94. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macrae DJ. The Council for International Organizations and Medical Sciences (CIOMS) guidelines on ethics of clinical trials. Pro Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:176–9. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-011GC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh JA, Karim SS, Karim QA, Mlisana K, Williamson C, Gray C, et al. Enrolling adolescents in research on HIV and other sensitive issues: Lessons from South Africa. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paterson BL, Gregory D, Thorne S. A protocol for researcher safety. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:259–69. doi: 10.1177/104973299129121820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]