Abstract

Background:

Gestational diabetes is one of the most common health problems in pregnancy that requires participation through self-care to reduce the maternal and neonatal complications. The present study aimed to determine the needs of women as an essential first step to formulate a self-care guide fitting the Iranian culture.

Materials and Methods:

The present qualitative study was conducted through interviews with 13 diabetic pregnant women and 10 care providers using semi-structured questionnaires in several cities of Iran in 2016. Further, the data analysis was performed using conventional content analysis. In addition, purposive sampling was performed at the diabetes clinic of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Imam Reza Hospital, and health centers across Kermanshah, Shahroud, and Tehran.

Results:

In the present qualitative content analysis study, four themes were identified: awareness and ability (knowing diabetes, mothers training and empowerment, continuity and quality, information resources), lifestyle (healthy diet, physical activity), mental health (counseling, interaction, spirituality, and religion), and supportive family (the husband's unique role, the psychological atmosphere at home).

Conclusions:

The present study highlighted main aspects of self-care educational/supportive needs, specifically in the domains of lifestyle, awareness and capability, mental health, and family. The results of our analysis highlighted the needs that can be useful for developing comprehensive self-care educational programs, with a higher focus on physical activity, mental health, the role of the family, and the use of religious interests.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes, high-risk pregnancy, qualitative study, pregnancy, self-care education

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a kind of hyperglycemia and one of the most common health problems in pregnancy. In this regard the development of insulin resistance in pregnancy, known as “gestational diabetes mellitus,”[1] and its mismanagement can bring about obstetric complications for mothers and babies. With the prevalence of obesity and diabetes in women at childbearing ages, the prevalence of hyperglycemia in pregnancy has been on the rise. Having used the new diagnostic criteria in an international multicenter clinical trial, it was reported that 18% of pregnancies were accompanied by gestational diabetes.[2] In addition, women with gestational diabetes as well as children born to mothers with any kind of hyperglycemia are at risk of type 2 diabetes in future.[1,3]

According to the policies of International Diabetes Federation (IDF), more effective training and lifestyle changes are required to improve the detection and management of diabetes.[4] Therefore, the educational and supportive self-care programs are among the health necessities in any society.[5] According to WHO (2013), self-care means the ability of individuals, families, and communities to improve health, prevent diseases, and maintain health and adapt to illness and disability with or without the support of healthcare providers.[6] Nowadays, the self-care education has changed from a purely educational and passive approach to awareness, decision-making for empowerment and self-care. Self-care education and self-care support are two essential elements for diabetes care and should be provided as soon as diabetes is diagnosed.[5]

Most studies in the world focus on women's experience of life with gestational diabetes.[7,8,9,10] A group of researchers investigated the factors that predispose and prevent self-care from the viewpoint of women or care providers.[11,12,13] Only two qualitative studies in Iran were carried out in this regard, whose results indicated that, mothers required more information through care providers and more support from their relatives for self-care.[14] It was also shown that there was a higher need for general education of families and training of diabetes nurses educators for higher compliance of treatment.[15] Considering the diversity of the subjects and the research procedure in existing studies, it seems that the real and comprehensive needs for self-care education in gestational diabetes are not yet clear. Therefore, studies focusing on women and care providers at the same time to examine the self-care needs of gestational diabetes and the cumulative analysis of their views can lead to a more complete explanation of the needs and provide a more detailed view to formulate the self-care education curriculum.

To successfully formulate and implement training programs, some essential factors should be taken into consideration, including needs assessment, determining barriers, and facilitators engaged in self-care to develop training programs properly, the relevance and fitness of the content of the program with the culture of the society, and preparing the national standards of diabetic self-care during pregnancy.[5,16,17,18,19] Unfortunately, there are no guide or guidelines in the field of self-care education of gestational diabetes in Iran, and the previous studies have focused on the prevalence or complications of the disease. Hence, it seems that there is not a clear understanding of the self-care educational needs to provide a basis for the guide. Considering that qualitative research is often done in cases where there is not enough knowledge of the phenomena, whereby the behaviors, views, feelings, and experiences of the people are identified,[20] and the fact that the views of patients, health workers, or managers can be used in qualitative studies in the field of health care,[21] the present study aimed to determine the needs of women as an essential first step to formulate a self-care guide fitting the Iranian culture.

Materials and Methods

The present qualitative content analysis study was conducted through semi-structured individual interviews with diabetic pregnant women and care providers using semi-structured questionnaire focusing on self-care educational needs. The interviews were conducted at the Diabetes Clinic of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Imam Reza Hospital, and health centers across Kermanshah, Shahroud, and Tehran in June and July 2016. The participants included pregnant women with diabetes. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria were pregnancy and diabetes (overt diabetes or GDM) with at least one month passing from their diagnosis of diabetes or commencement of their clinic care for diabetes, desire to participate in the study, non-mental illness, absence of other high-risk pregnancies. The exclusion criterion was refusal to continue interviews or participate in the study for any reason. Moreover, using the purposive sampling, the participants were diverse in terms of age, parity, education, occupation, experience and type of diabetes, and place of residence. The presence of participants with previous history of gestational diabetes or type 1 and type 2 diabetes in this study was aimed at enriching the data (according to their experience of self-care) and helping to define the needs of self-care more accurately and precisely.

As for care providers, interviews were conducted with specialists and health care personnel with at least one year of experience in providing service to the diabetes pregnant women and desire to participate in the study. The interviews were conducted by the first author after arrangement by telephone or meeting to set the date, time and place of the interview. This group consisted of specialists and staff of the diabetes clinics, health care centers and hospitals [Tables 1 and 2]. In addition, diversity was considered in care providers in terms of specialty, type of service, and work experience. The pregnant mothers were interviewed in one of the rooms of the clinics or health centers in a quiet and private atmosphere. The specialists and staff were interviewed in the diabetes clinics and their own offices in Imam Reza Hospital after office hours.

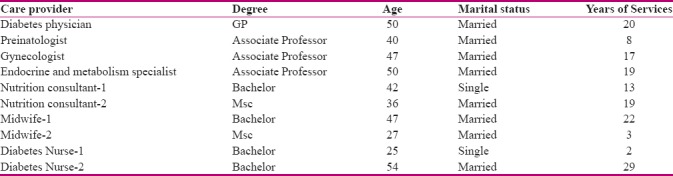

Table 1.

Characteristics of care providers

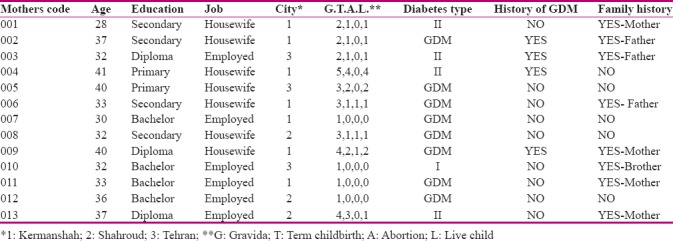

Table 2.

Characteristics of mothers

To collect data, some semi-structured interviews, taking 50 minutes at the most, were conducted with voice recording. The interviews began by asking general questions, such as “What to do to take care of your health and your fetus?” After the completion of each interview, the content was written on papers and coded. Data was analyzed with completion of all interviews. The previous interviews provided guidelines for subsequent ones, whereby the questions were revised. Further, data collection continued until reaching the saturation (repeated data and not new data), which increased the reliability.

The written content of the interviews was reviewed for several times. Then the researchers repeatedly read the interviews word by word with the aim of immersion in data and extraction of meaning units and wrote them in the form of initial codes. Meaning units were reviewed several times and classified according to the conceptual and meaning similarity. Then, categories and subcategories were compared with each other and the analysis and interpretation of these lead to extraction of themes.

According to the Lincoln and Guba's evaluative criteria (1985), member check, peer check, immersion in data, prolonged engagement with participants in data collection period, immediate recording of each interview, concurrent analysis of data and increased diversity in characteristics of participants were taken into consideration.[22]

Ethical considerations

After obtaining the approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences and the agreement of the President of the diabetes clinics and health centers as well as the participants' signed consent, the interviews were conducted. The people participated voluntary and had the right to refuse to participate in the study without the need to provide a reason. The ethical code is IR.SHMU.REC.1394.23.

Results

There were 23 participants in this study (10 care providers and 13 pregnant women with diabetes). The mean age of pregnant women with diabetes and care providers was 34.6 years and 37.8 years, respectively. Further, the care providers had an average work experience of 15.1 years [Table 1]. In terms of diabetes, eight of the pregnant women had GDM, and five were suffering from type 1 and 2 diabetes [Table 2]. In the present study, four themes were identified: awareness and capability, lifestyle, mental health and family [Table 3].

Table 3.

Study themes, categories, and subcategories

Awareness and ability

As for diabetes and its self-care during pregnancy, mothers and care providers needed to gain some knowledge and skills in this respect. The awareness and ability theme fell into four categories: need to know diabetes, mothers training and empowerment, continuity and quality, and Information resources.

Knowing diabetes

The interviews indicated that one's understanding of diabetes was considered the first step in the treatment compliance and making recommendations. According to the mothers, diabetes was unknown or they had little information about it. One of the mothers said:

“I should have enough information about my disease and medications. I should know about the rise and fall of my blood sugar and know what to do. The fall of blood sugar is very common at midnight, and I should know what to do when I have no access to doctors.” (Mother-code 0013).

“To control diabetes, mothers should know which foods to consume, how to divide their courses, how to control their blood sugar, what factors increase their blood sugar, and when to visit doctors.” (Nutrition consultant-1).

Mothers' training and empowerment

Care providers believed that women had to acquire skills and abilities in the monitoring of blood glucose, insulin injection, and adjustment of its dose as well as planning healthy nutrition. Furthermore, the required competences and skills, such as adaptation and disease management skills were raised by mothers:

“We need information to be able to know about the disease and how to cope with it because we have not caught this disease.” (Mother-code 007).

“Training should be provided in a manner that one is capable of dealing with problems and one's disease.” (Nurse-1).

Continuity and quality

One of the main findings of the present study was the mothers' need for quality and continuous counseling and education. They felt that they were in need of the required information to cope with the disease in reality, and the present education could not meet their needs. The other is mothers and care providers concurred with the idea that the training should be in line with the personal needs of visitors.

“I feel that I should speak with a consultant every time I visit the clinic. For example, if the disease is under control, it is better that the doctor or the midwife tell me whether it is controlled to not, and tell me what to do and not to do. I suppose, they should explain what we should do, and having a consultant at our side is very helpful.” (Mother-code 009).

“Sometimes, we have to train mothers that are slow. Therefore, they should be presented with slow training and even some of them should be spoken with their own local language. In other words, if we have friendly relationships with them, they will understand us more easily and the self-care is better performed.” (Midwife-2).

Information resources

One of the significant gaps for mothers was the lack of knowledge about pregnancy and diabetes. They were only given one or two sheets of paper about proper feeding, symptoms, and how to deal with changes in blood sugar. Moreover, they were not provided with any books, pamphlets, brochures, or educational packages about the management of diabetes in pregnancy. The mothers and care providers stated that:

“I only have a paper reading: 'when you feel you are tired and without energy, it means that your blood sugar is low.' I study these papers, but I do not learn anything.” (Mother-code 008).

“We don't have any training guides about gestational diabetes. Now, the educational resources on gestational diabetes are very limited, and their material is abstracted in one or two pages.” (Midwife-1).

Lifestyle

The results demonstrated that care providers had clearer views about the lifestyles of the general public, while mothers did not have correct definitions or comments about healthy feeding or the need for physical activity, especially during pregnancy. Some of the needs and necessities announced by mothers and care providers were suitable exercises during pregnancy, and nutrition knowledge and management.

Exercises during pregnancy

The results revealed that the awareness of women regarding suitable exercises during pregnancy was very low and limited. Moreover, exercises during pregnancy are still considered by doctors with extreme caution. In addition, women are not often provided with serious advice on suitable exercises during pregnancy. For example, a pregnant woman expressed that:

“Nobody told me anything about the necessity of exercise in diabetes clinics. My own doctor did not tell me anything.” (Mother-code 010).

“I think exercise is very efficacious in controlling blood sugar, but I don't have any idea which sports I should play.” (Mother-code 0011).

Healthy diet

The results indicated that mothers were provided with limited information about healthy diet. On the other hand, due to the small number of personnel, it was not possible to offer quality counseling and training. Moreover, mothers and care providers expressed that there had to be more detailed and practical training in this regard. Also, care providers explicitly expressed the need for detailed and practical training in different parts of nutrition, ranging from different types of foods to healthy cooking styles.

“The nutrition education was inadequate, because they only told us to consume less rice and few baked potatoes and to eat more fish. They did not tell us anything about how to substitute foods or how to consume better foods.” (Mother-code 005).

“We need to be educated to consume less oil, steam more foods and use different methods of cooking except frying. If we can consume less rice or bread and eat more vegetables, it will be very good, and a big step will be taken in this respect”. (Perinatologist).

Mental health

Different sources of stress, mental pressures and the need for mental health services were addressed in detail by mothers and care providers. Mental health fall into three categories: counseling, interaction, and spirituality and religion.

Counseling

The results showed that counseling and psychological support, including training the stress reduction techniques, are some of the most basic educational needs of gestational diabetes self-care. There are no psychologists in diabetic clinics and most health centers. Also, care providers stressed the need for psychological counselling and services for diabetic pregnant mothers.

“If I am mentally supported, it will be better than anything else. If one is in good spirits, he/she can do the rest.” (Mother-code 006).

“These mothers need psychological services because they are under a lot of stress. In my personal opinion, they should go and see psychologists to be mentally relieved, and they should be educated about stress control and reduction techniques.” (Nutrition consultant-1).

Interaction

The results revealed that mothers cared very much about how doctors treated them and others and needed positive interaction from the doctors' part. Moreover, the role of interaction and paying attention to mothers are considered by care providers more important than just focusing on a number (e.g., blood sugar).

“Doctors can help patients by talking to them. Some doctors talk in a way that one's blood sugar goes up and vice versa. Some doctors relieve patients mentally by their information and comfort. By doing so, doctors can make us think, 'my disease is not that much dangerous. So, I can cope with it.' Today, my doctor told me to write down my blood sugar value, and said, 'If there is a problem, I will let you know,' but, by contrast, another doctor told me that my blood sugar measured A1c and told me to have an abortion.” (Mother-code 013).

“Sad to say, most doctors discuss the blood sugar control. Instead, if we devote 10 minutes, or even five minutes to talking to mothers, it will bring about better results. In my opinion, supporting them mentally is much more important.” (Endocrinologist).

Spirituality and religion

The results of the present study indicated that this aspect of health had a religious feature, which is underscored at the time of pregnancy. In this study, care providers and women pointed to the presence of God and belief in the will, his blessings, and the resulting relaxation.

“Well, perhaps, good spirits are important for all. The way I see it, sometimes you are fed-up with yourself, but after connecting with God, everything will be in the hands of God, and he will show his mercy. Therefore, when I am done with prayers, I am relieved.” (Mother-code 007).

“I do my best to direct the attention of other mothers to God and remind them that it has been God giving them children and has done them a favor, and they should prepare themselves for everything because they may have no more children because it is in God's hands.” (Nutrition consultant-2).

Supportive family

The results demonstrated that family played a vital role in the health of pregnant women and their fetuses. This role was also underscored by care providers, but they expressed that they did not have much time for family education due to busy hours. This section falls into two categories: the husband's unique role, and the psychological atmosphere at home.

Husband's unique role

The results of the present study demonstrated that the husbands' emotional attention and presence were important for their wives, but some were deprived of special attention from their husbands, and they were only accompanied to clinics. It should be noted that care providers pointed to the defects in the roles that husbands should play in society to manage diseases.

“My husband helps me physically and mentally a lot. For example, when I go to the clinic, he takes a day off and accompanies me there. This kind of behavior is very important for me.” (Mother-code 002).

“Sometimes, our problems are related to the husbands of pregnant women. Sometimes, their husbands say that they give birth to defective children due to many insulin injections, and sometimes, they tell their wives to have abortions because they are unwanted children.” (Diabetes nurses-1).

The psychological atmosphere at home

The need for peace and its insufficiency in some houses were often mentioned by women. In the culture of some Iranian regions, living with the paternal family of the husband is still common. Therefore, the effects of their attitudes and behaviors, especially during pregnancy, are more evident. Mothers mentioned that the bustling atmosphere of family and lack of understanding the conditions of the pregnant women led to high stress in them.

“Peace of mind is vital. Stress makes the blood sugar go up. In my opinion which is shared by family members and relatives, when the rules are obeyed and there is no tension in the house, it is peace.” (Mother-code 012).

“I have a lot of stress because our family is very bustling. When one of the siblings of my husband has a problem, he/she comes to our house to solve them.” (Mother-code 001).

The care providers believed that families should be trained to support mothers, thereby reducing their stress.

“Families should reduce the stress of mothers and help them cope with their problems more easily. For example, children should not ask for separate dishes and let the mother choose more suitable food.” (Diabetes physician).

Discussion

The results of examining the educational needs of mothers and care providers demonstrated that mothers in Iran had a series of educational and counseling needs as shared by other mothers in the rest of the world. What makes this sharing somewhat different is “the types of needs” in the field of awareness and skills, so that two categories of continuity and quality and information resources in the theme of awareness and abilities represent gap and significant needs in raising awareness and empowerment. In other clinical trials, women and care providers expressed that limitations and inadequacies of the type and amount of provided information increased their confusion over glycemic control and self-care. They also stated that they did not receive enough information and guidance to make the necessary changes.[23,24,25,26] The notable issues in the present study were mother's needs and attention to how education and counseling were presented, indicating the needs beyond getting the primary information. They needed to get qualitative, practical, and consistent education and counseling, thereby leading to their ability to handle situations as well as compatibility with special conditions of disease control. Another issue in this theme was the lack of reliable and available educational resources. There were shortages of written information,[27] and there was a need for written educational materials and their roles in improving diseases in other studies.[28] The findings of the present study can serve as a suitable guide for mothers at the time of disease.

Additional stress in diabetic pregnancy requires the need for special, immediate, and continuous health services whose significant lack has been felt by mothers and care providers. In the few guides in the world, this need has been addressed superficially, and relaxation or breathing techniques have been mentioned in the form of short phrases.[29,30,31] The present study showed that, in addition to the needs for counseling services, the engagement of care providers (especially the interest and involvement of physicians in the Iranian culture) in relaxation as well as the mothers' commitment to treatment and admission were very effective in this regard. In a study conducted by Carolan et al. (2012), care providers and husbands were two main sources of emotional support from the perspective of women.[32] Rodriguez (2013) believed that the good clinical relationship between the patients and care providers leads to patient's further participation in self-care, thereby bringing about better diabetic results.[33] It seems that there should be an appropriate and special interaction in training care providers, which in turn will be considered in training and advising mothers.

As for mental health, there are some aspects of needs that are somewhat special in the Iranian culture and society, which can be identified and help with formulating a comprehensive education and counselling program. One of these items is the spiritual needs in Iran that are somewhat different from other countries because religion plays a strong role in beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of Iranian women at the time of pregnancy. In the present study, the majority of mothers talked about reliance on God for the health of themselves and fetuses. Similarly, in a study done by Mendelson et al. (2008), in parish nursing, patients were encouraged to say their prayers and connect with God according to their religious beliefs.[34] While religious and spiritual beliefs constitute a vital part of many people's attitudes about life and how to adapt themselves to it,[35] and despite the emphasis on cultural sensitivity and the fit between recommendations with culture, especially in medical nutrition therapy,[36,37] little attention is paid to the spiritual and religious beliefs in education and guides. It should be noted that considering the spiritual beliefs, especially during pregnancy, could cause relaxation, grow hope and commitment to carry out the recommendations.

In the supportive family theme, awareness and protection and paying attention to the role of the husband from different dimensions reflect the husband's unique role in the mental health of the mother and management of the disease from the perspective of mothers. Mothers often explicitly talked about the need for emotional support and attention from their husbands. Studies have stressed that, in addition to improving lifestyles, husbands and family members could provide mothers with mental and emotional support.[15,23,32] It seems that this need, which is largely linked to maternal mental health, should be seen especially in education and counseling programs provided for husbands and other family members.

The need for lifestyle modification and correcting misconceptions was a central theme in this study. Mothers and care providers pointed to the misconceptions about certain lifestyles during pregnancy in the Iranian culture, which doubled the importance of the issue. The beliefs stating that pregnant women should eat twice as much food as the normal people do or the belief that mothers need much more sleep in pregnancy make diabetes management in pregnancy more difficult. The necessity of lifestyle modification has been stressed in most studies.[10,12,38,39,40] In a study conducted by Jones et al. (2009), the necessity of lifestyle modification was emphasized in pregnant women.[38] The findings of the present study indicated that, in addition to culture and beliefs in life, the special cultural beliefs during pregnancy should be considered in training.

One of the limitations of the present study was the lack of familiarity of a number of participants with the scientific concept of self-care, which was attempted to be explained more closely to their understanding. Also, the number of Iranian articles in this field was very low, so more were used to discuss articles from other countries.

Conclusion

The present study revealed the main aspects of self-care educational/supportive needs in domains of lifestyle, awareness and capability, mental health and family. The result of analyzed expressed needs can be a useful guide for developing comprehensive self-care educational programs, with focusing more on physical activity, mental health, the role of the family, and the use of religious interests. Sharing these needs and views in the international area leads to formulating more comprehensive international guides and instructions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Shahroud University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participation of all mothers and care providers. This study was derived from a PhD dissertation on reproductive health at Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The ethical code is IR.SHMU.REC.1394.23.

References

- 1.Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, et al. Williams obstetrics. 24th ed. USA: McGraw Hill education; 2016. pp. 1125–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: National estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United State, 2011. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coustan DR. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Glycemic control and maternal prognosis. Topic 6790 Version 69.0. 2016. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 29]. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-diabetesmellitus-glycemic-control-and-maternal-prognosis?source=see_link.

- 4.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes atlas. 7th ed. 2015. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 22]. Available from: www.idf.org/diabetesatlas.

- 5.Crawford K. Review of 2017 Diabetes Standards of Care. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;52:621–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webber D, Guo ZH, Mann S. Self-care in health: We can define it, but should we also measure it? [Last accessed on 22 Nov 2017];Self Care. 2013 4:101–6. Available from: http://selfcarejournal.com/tag/self-care/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devsam BU, Bogossian FE, Peacock AS. An interpretive review of women's experiences of gestational diabetes mellitus: Proposing a framework to enhance midwifery assessment. Women Birth. 2013;26:e69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolan JA, McCrone S, Chertok IR. The maternal experience of having diabetes in pregnancy. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:611–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison MK, Lowe JM, Colins CE. Australian women's experiences of living with gestational diabetes. Women Birth. 2014;27:52–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandyopadhyay M, Small R, Davey MA, Oats JJ, Forster DA, Aylward A. Lived experience of gestational diabetes mellitus among immigrant South Asian women in Australia. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51:360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui A, Sevenhuysen G, Harvey, Salamon E. Barriers and coping strategies of women with gestational diabetes to follow dietary advice. Women Birth. 2014;27:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chávez-Courtois M, Graham C, Romero-Pérez I, Sánchez-Miranda G, Sánchez-Jiménez B, Perichart-Perera O. Experiences, perceptions and self-management of gestational diabetes in a group of overweight multiparous women. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:1643–52. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014196.02452013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carolan M, Gill GK, Steel CH. Women's experiences of factors that facilitate or inhibit gestational diabetes self-management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emamgholi Khooshehchin T, Keshavarz Z, Afrakhteh M, Shakibazadeh E, Faghihzadeh S. Explanation the experiences of mothers with gestational diabetes about the factors affecting self-care: A qualitative study. [Last accessed on 13 Sep 2017];J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2016 5:76–89. Available from: http://eprints.skums.ac.ir/4910/. [In Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaffari F, Salsali M, Rahnavard Z, Parvizy S. Compliance with treatment regimen in women with gestational diabetes: Living with fear. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Research. 2014;19:S103–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Education and Health Promotion. Service pack of self care, cooperation and participation of urban and rural health centers. Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Deputy of Health. Office of Education and Health Promotion. 1th ed. 2014. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 08]. Available from: http://www.phc.umsu.ac.ir/uploads/9_371_90_1.pdf. [in persian].

- 17.Rutledge SA, Masalovich S, Blacher RJ, Saunders MM. Diabetes self-management education programs in nonmetropolitan counties-United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66:1–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6610a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hass L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, Cox CE, Duker P, Edwards L, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes care. 2012;35:2393–401. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NICE guideline. Diabetes in pregnancy: Management diabetes in pregnancy: Management from preconception to the postnatalfrom preconception to the postnatal periodperiod. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 25]. Available from: nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3 .

- 20.Pilot D, Hungler B. Nursing research. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2002. pp. 349–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanee AS, Nikbakht AR. Methodology of qualitative research in medical sciences. Tehran, Iran: Publisher for Tommarow; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carolan M, Gill GK, Steele C. Women's experiences of factors that facilitate or inhibit gestational diabetes self-management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mersereau P, Williams J, Collier SA, Mulholland C, Turay KH, Prue CH. Barriers to managing diabetes during pregnancy: The perceptions of health care practitioners. Birth. 2011;38:142–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Holanda VR, de Souza MA, dos Santos Rodrigues MC, Pinheiro AK, Damasceno MM. Knowledge of pregnant women about gestational diabetes mellitus. [Last accessed on 6 Dec 2017];Journal of Nursing UFPE on line [JNUOL] 2012 6:1648–54. Available from: http://www.revista.ufpe.br/revistaenfermagem/index.php/revista/article/download/2956/4056. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirst JE, Tran TH, Thi Do MA, Rowena F, Morris JM, Jeffery HE. Women with gestational diabetes in Vietnam: A qualitative study to determine attitudes and health behaviours. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2012;12:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindmark A, Smide B, Leksell J. Perception of healthy lifestyle information in women with gestational diabetes A pilot study before and after delivery. [Last accessed on 6 Dec 2017];Eur Diabetes Nursing. 2010 7:16–20. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/edn.150/epd. doi: 10.1002/edn.150. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell J. Reducing barriers to glucose control in patients with gestational diabetes. American Nurse Today January 2015. [Last accessed on 2 Dec 2017]. Available from: www.AmericanNurseToday.com.

- 29.Califorina Department of Public Health. Gestational Diabetes: All you need to know about you and your baby © Califorina Department of Public Health. 2014. Jun, Available from: http://www.cdappsweetsuccess.org/Portals/0/Documents/Gestational%20Diab/GDMbooklet_engl_2014.pdf.

- 30.Ransdell A and the Perinatal Providers and Staff. Gestational diabetes. A CDAPP Sweet Success Affiliate Program. CommuniCare Health Centers, Davis, California. 2013. Jan, [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.sweetsuccessexpress.com/RESOURCES.html.

- 31.Dietetic department. King Edward Memorial Hospital. Dietetic department. Healthy eating for gestational diabetes. 2013. Jan, Available from: http://kemh.health.wa.gov.au/brochures/consumers/wnhs0560.pdf.

- 32.Carolan M, Gill G, Steel CH. Women's experiences of gestational diabetes self-management: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2013;29:637–45. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez KM. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting patient engagement in diabetes self-management: Perspectives of a certified diabetes educator. Clin Ther. 2013;35:170–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendelson SG, McNeese-Smith D, Koniak-Griffin D, Nyamathi A, Lu MC. Community-based Parish nurse intervention program for Mexican American women with gestational diabetes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:415–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorig K, Holman H, Sobel D, Laurent D, Gonzalez V, Minor M. Living a healthy life with chronic conditions. 3th ed. Bull publishing company; 2006. pp. 87–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, Hadar E, Agarwal M, Di Renzo GC, et al. Management of hyperglycemia during pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;131:S173–211. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(15)30033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Diabetes Federation. Global guidline. Pregnancy and diabetes. © International Diabetes Federation. 2009.

- 38.Jones EJ, Roche CC, Appel SJ. A Review of the health beliefs and lifestyle behaviors of women with previous gestational diabetes. J Obstet Gyanecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38:516–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razee H, van der Ploeg HP, Blignault I, Smith BJ, Bauman AE, McLean M, et al. Beliefs, barriers, social support, and environmental influences related to diabetes risk behaviours among women with a history of gestational diabetes. Health Promot J Austr. 2010;21:130–7. doi: 10.1071/he10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wazqar DH, Evans MK. Socio-cultural aspects of self-management in gestational diabetes. [Last accessed on 6 Dec 2017];J Diabetes Nurs. 2012 16:62–7. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/edn.150/epd. [Google Scholar]