Abstract

An understanding of the pathogenesis of infection with the Zika virus in the male reproductive tract is vital for the development of vaccines and antivirals that will limit or prevent sexual transmission. Two common immunocompromised mouse strains used in transmission studies—male with genes encoding interferon types I and II receptor gene knockout (IFNAR/IFNGR; AG129) and with interferon type 1 receptor knockout (Ifnar−/−) were infected with a Puerto Rican Zika virus isolate (PRVABC59), and pathology was assessed 5 to 11 days after infection. Virus was detected by immunohistochemistry and quantitative RT-PCR in the testicle and epididymis of AG129 and Ifnar−/− mice, and by immunohistochemistry in the prostate and seminal vesicle of infected AG129 mice. Severe disease manifestations initiating as epididymitis and progressing to orchitis were observed in both models, with more severe inflammation noted in the AG129 mouse strain. Significant inflammation was not observed in any evaluated accessory sex gland at any point during infection. Time–course analysis of infection revealed an increase in the severity of disease within the epididymis of both strains, indicating a potential route of sexual transmission. Male mice with Ifnar−/− may better recapitulate Zika virus in humans and provide insight into the mechanism of sexual transmission, due to milder histopathologic lesions, the presence of histologically normal sperm in epididymal tubules, and an ability to survive the acute phase of disease.

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a single-stranded RNA virus of the genus Flavivirus. Originally isolated in Uganda in 1947,1 ZIKV has caused relatively few outbreaks with limited disease.2, 3, 4 The typical clinical symptoms of ZIKV include fever, rash, transient joint pain, conjunctivitis, muscle pain, and headache (https://www.cdc.gov/zika/symptoms/symptoms.html, last accessed August 5, 2017). Recent outbreaks in Central and South America have coincided with an increase in congenital malformations,5, 6, 7 with congenital microcephaly having recently been linked to in utero ZIKV infection.8, 9, 10 Although congenital malformations are associated with in utero ZIKV infection, there are limited data from humans available for the evaluation of the potential long-term systemic consequences of ZIKV infection in adults.

The natural route of transmission of ZIKV is through mosquitoes of the genus Aedes,11 with A. aegypti and A. albopictus being the most biologically important urban species in epidemic transmission.12, 13 However, mounting case reports of disease in ZIKV-naïve individuals after sexual contact with an infected male suggest that sexual transmission is a viable route of the natural spread of the infection in humans.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 A single case report also described potential sexual transmission from an infected female to a male partner.6 ZIKV is present in the semen of infected men for weeks to months after the initial onset of the disease.19, 20 Virus may also be detected in the semen of vasectomized males,21 suggesting the presence of virus in accessory sex glands. However, no data currently exist that directly show active infection of the primary or accessory male reproductive tissue. Furthermore, there are no clinical or experimental data at present that characterize the pathologic state of the entire male reproductive tract during active ZIKV infection.

The male reproductive tract consists of the testicle (Figure 1A) and associated tubular components: the epididymis (Figure 1D), vas (ductus) deferens, and urethra. The tubular structures are lined by a single layer of epithelial cells and function as a transit pathway for sperm from the testicle to the penis. Along the tubular structures lie the accessory sex glands, which provide nutritional support to spermatozoa and enhance the volume of ejaculate with fluid and mucous components.22 In humans, the accessory sex glands include the prostate gland, seminal vesicles, and bulbourethral (Cowper) glands. In addition to the accessory sex glands as present in humans, mice have additional accessory components, including the ampullary glands, outpouchings of the ductus deferens, and preputial glands.22 Although the accessory sex glands vary in morphologic organization, they are all composed of or lined with epithelial cells. Members of the family Flaviviridae frequently exhibit tropism for epithelial cells,23 and we hypothesize that the epithelial cells of the male reproductive tract serve as a source of reproductive infection for ZIKV.

Figure 1.

A: Interferon type I and II receptor gene knockout (AG129) control testicle. Seminiferous tubules are supported by a distinct basement membrane (black arrow) and lined by Sertoli cells and spermatogonia. Within the lumen of each tubule are moderate numbers to numerous maturing spermatozoa (arrowhead). The interstitium contains small blood vessels, which are abutted by Leydig (interstitial) cells (white arrow). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. B: AG129 testicle, 9 days after infection (DPI). The interstitium is infiltrated by neutrophils (arrow). There is loss of orderly maturation and necrosis of spermatids, and necrosis of tubular cells (arrowhead). H&E stain. C: Interferon type I receptor gene knockout (Ifnar−/−) testicle, 8 DPI. The interstitium is multifocally infiltrated and expanded by low numbers of neutrophils (arrow). Seminiferous tubules contain abundant maturing spermatids and spermatozoa. H&E stain. D: AG129 control epididymis. Tubules are lined by a single layer of tall, columnar epithelial cells with stereocilia, and tubular lumens contain numerous maturing spermatids (arrow). The interstitial spaces are populated by low numbers of fibroblasts and rare lymphocytes within a fine fibrovascular stroma. H&E stain. E: AG129 epididymis, 7 DPI. Variable numbers of tubular epithelial cells are undergoing necrosis (arrow). Diffusely, tubules contain necrotic epithelial cells admixed with maturing spermatozoa (arrowhead). H&E stain. F:Ifnar−/− epididymis, 8 DPI. Low numbers of tubular epithelial cells undergo single-cell necrosis (arrow) and slough into the tubular lumen. Tubules contain abundant maturing spermatozoa. The interstitium is multifocally infiltrated by low to moderate numbers of inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes and fewer neutrophils (arrowhead). H&E stain. Original magnification: ×20 (A, D); ×40 (B, C, E, F). Scale bars: 100 μm (A, D); 50 μm (B, C, E, F).

ZIKV has been detected by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) in testicle homogenates of several mouse models of ZIKV infection,24, 25, 26 as well as in epididymal epithelial cells.27 A ZIKV-infected testicular germ cell line (833 KE) and prostatic cell line (LNCaP) have been described.28 However, the initial target cell type(s) for ZIKV infection in the male reproductive tract have yet to be identified. Accessory sex glands have yet to be specifically evaluated as a primary source of infection in the male reproductive tract. It is unknown whether spermatozoa serve as the primary source of infection during sexual transmission, or whether the source of sexually transmitted virus originates in the accessory sex glands. To better characterize the disease progression of ZIKV in infected males, and to identify potential routes of sexual transmission, a thorough evaluation of the progression of histopathologic lesions in the male reproduction tract is provided herein. This evaluation includes a description of events, from the initiation of inflammation through systemic disease and subsequent death, with a viral isolate clinically relevant to the outbreak of ZIKV in the Western hemisphere.

AG129 mice lack receptors for IFN-α/β and -γ,29 whereas Ifnar−/− mice lack only the IFN-α/β receptor.30 Both mouse strains have previously been shown to support active ZIKV systemic infection.24, 25, 31 A direct comparison of the reproductive disease phenotype in these immunocompromised mouse models utilizing the same clinically relevant ZIKV isolate has not yet been performed. In the present study, we characterize the histopathologic effects of ZIKV on the primary and accessory male reproductive structures in AG129 and Ifnar−/− mice, show target-cell specificity of the male reproductive tract, show that ZIKV infection initiates as an epithelial cell infection, and propose two potential routes of sexual transmission. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first detailed characterization of leukocyte infiltration, inflammation, and positive viral identification in the epididymis, and the first report of positive ZIKV infection of the accessory sex glands in a mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All studies were conducted with the approval of the Utah State University Institute for Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 2598). Study approval and animal care were conducted in accordance with The Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals32 and the US Government Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research, and Training (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/tutorial/relevant.htm#2b, last accessed September 10, 2016).

Mouse Experimentation

To evaluate the extent of reproductive pathology in acute infection with ZIKV, AG129 male mice between the ages of 7 and 8 weeks and Ifnar−/− males ages 3, 6, and 16 weeks were infected s.c. with 102 plaque-forming units of the PRVABC59 strain of ZIKV diluted in a volume of 100 μL of minimal essential medium (MEM; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) along the medial aspect of the right thigh. The PRVABC59 virus stock was prepared by passaging twice in Vero76 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) before inoculation. Sham-infected animals were administered 100 μL of MEM solution in the same manner. Two control and two infected mice were sacrificed at 5 days after infection (DPI). Three control and eight ZIKV animals were sacrificed at 7 DPI. One sham-infected and five ZIKV-infected animals were sacrificed at 9 DPI. A >20% weight loss, accompanied by a hunched stance and neurologic deficits, was observed in four ZIKV-infected animals at 10 DPI, and humane euthanasia was elected for these animals and one sham-infected animal. The study was terminated at 11 DPI, and two sham-infected and five ZIKV-infected mice were sacrificed and processed. Euthanasia was performed by carbon dioxide gas administration.

For all sacrificed animals, reproductive tissue was collected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and processed for histopathology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis as previously described.33 Fresh samples of one testicle and associated epididymis were collected from each mouse at each time point, and the prostate and seminal vesicle were collected from a singular infected mouse at each time point. The fresh tissue was weighed, then homogenized in 1 mL of MEM solution (HyClone Laboratories) and frozen at −80°C. A 100 μL aliquot of homogenized tissue in MEM was mixed with 900 μL of TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and immediately frozen at −80°C for molecular evaluation.

To evaluate the extent of reproductive pathology in acute infection with ZIKV in the Ifnar−/− strain male mice, three groups of mice (3, 6, and 16 weeks) were infected s.c. with PRVABC59 ZIKV strain or vehicle as described earlier in this section. Three mice from each treatment group were randomly selected at 5, 8, and 11 DPI for necropsy. Three 6-week-old Ifnar−/− males were sham-infected as described earlier in this section, and one was sacrificed at each time point. All animals in the 3-week-old group were humanely euthanized at 6 or 7 DPI due to weight loss, lethargy, hunched stance, or inability to move from a lateral recumbent position. Fresh samples of testicle, epididymis, spleen, liver, kidney, and brain were processed as described earlier in this section for molecular analysis. Reproductive tissue was collected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and processed as described earlier in this section.

Histopathology

Following fixation, tissues were processed routinely and embedded in paraffin wax, and serial sections of 5-μm thickness were made. The first slide was prepared for hematoxylin and eosin staining, and the subsequent slides were prepared for IHC analysis. Independent and blinded histopathologic evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides was performed by two veterinary anatomic pathologists (C.S.C. and A.J.V.W.).

An inflammatory scoring scheme specific to the testicle and epididymis was generated following brief slide review by the pathologists and utilized for grading the inflammatory response (Table 1). The scoring system was used for evaluating the degree interstitial (intertubular) inflammation by a count of interstitial leukocytes on the following scale: 0 indicates a lack of leukocyte infiltrates; 1 indicates 1 to 5 leukocyte infiltrates; 2 indicates 6 to 10 leukocytes forming aggregates; and 3 indicates 10+ leukocytes forming aggregates or sheets. The degree of tubular necrosis and inflammation was assessed by an evaluation for epithelial or spermatogonia necrosis and accumulation of leukocytes within tubules on the following scale: 0 indicates a lack of necrosis or degeneration; 1 indicates individual cell necrosis or degeneration; 2 indicates entire tubule necrosis or degeneration; and 3 indicates entire tubule degeneration and necrosis accompanied by leukocyte infiltration. The interstitial inflammation and tubular inflammation and degeneration scores were based on a single high-power (×400) field exhibiting the most severe histopathologic lesion. Lastly, the total amount (percentage) of the testicle or epididymis involved was scored on the following scale: 0 indicates up to 5% of tissue involvement; 1 indicates 6% to up to 25% of tissue involvement; 2 indicates >25% to 50% tissue involvement; and 3 indicates >50% tissue involvement. As interstitial necrosis was not observed in either the testicle or epididymis in this study, interstitial necrosis was not considered in inflammatory scoring. Interstitial leukocytes in the testicle and epididymis were observed only if >25% of the tubular epithelial or spermatic cells were undergoing necrosis and therefore the presence of tubular leukocytes was assigned the highest degree of inflammation in the category of interstitial inflammation and necrosis. The percentage of the testicle or epididymis involved included the findings from an evaluation of both tubular and nontubular components, regardless of whether the process was limited to one space or included both spaces. As presently recommended by the International Harmonization of Toxicologic Pathology Nomenclature,34 between-group differences in lesion severity score were not statistically analyzed. Instead, the raw data are provided in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Table 1.

Grading System for Testicular and Epididymal Inflammation

| Interstitial inflammation score∗ | Tubular inflammation and degeneration/necrosis score∗ | Tissue involvement score† | Total inflammatory score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0, Absent | 0, Absent | 0, 0%–5% | 0, None |

| 1, 1 to 5 individual leukocytes between tubules | 1, Individual spermatid/epithelial necrosis or degeneration | 1, 6%–25% | 1, Minimal |

| 2, 6 to 10 leukocytes between tubules in aggregates | 2, Entire tubule spermatid/epithelial necrosis or degeneration | 2, 26%–50% | 2–3, Mild |

| 3, >10 leukocytes forming sheets/aggregates between tubules | 3, Entire tubule spermatid/epithelial necrosis with intratubular leukocytes | 3, 51%+ | 4–5, Moderate |

| 6+, Severe |

The individual scores for interstitial inflammation, tubular inflammation, and amount of tissue involved were added and the total was used for generating an inflammatory score.

Inflammation and necrosis were graded based on a single high-power (×400) field receiving the highest score in the tissue; the amount of tissue affected by inflammation and necrosis was graded separately.

Based on the entire section of testicle or epididymis (both tubular and interstitial spaces).

IHC Analysis

Tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was achieved by placement of slides in decloaking solution (Dako, Agilent Pathology Solutions, Santa Clara, CA), within a decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA), and processed at 125°C and 20 psi for 4 minutes. The slides were allowed to cool to room temperature, then were exposed 0.5% Triton for 5 minutes, followed by four washes in phosphate-buffered saline for 5 minutes each. A blocking solution of 10% normal goat serum, 0.02% Triton, and 89.08% phosphate-buffered saline was applied to the slides for 30 minutes at room temperature. The blocking solution was removed and slides were incubated with a goat–anti-ZIKV polyclonal antibody (IBT Bioservices, Rockville, MD) at a dilution of 1:500 in blocking solution for 24 hours. Slides were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline for 5 minutes each, then incubated for 2 hours with rabbit–anti-goat antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) at a dilution of 1:500. For immunofluorescence, a mounting media containing DAPI was applied before the application and sealing of a coverslip. For IHC analysis, slides were incubated with peroxidase substrate solution (Dako, Agilent Pathology Solutions) for 10 minutes and then washed in phosphate-buffered saline. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and dehydrated, and a clear, permanent mounting media and a coverslip were applied.

Detection of ZIKV RNA

One hundred microliters of tissue homogenate in MEM was mixed with 900 μL TRIzol reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH), and RNA was extracted. RNA was suspended in RNAsecure (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and amplified by RT-qPCR. Ten microliters of 2× SensiFAST Probe No-ROX One-Step Mix (Bioline, Taunton, MA) with polymerase and reverse transcriptase, along with Malaysian ZIKV primers (20 μmol/L; forward: 5′-CTGTGGCATGAACCCAATAG-3′, reverse: 3′-ATCCCATAGAGCACCACTCC-5′) and probe (20 μmol/L; 5′FAM-CCACGCTCCAGCTGCAAAGG-3′ tetramethylrhodamine) labeled with a fluorescein amidite OR 6-carboxyfluorescein fluorophore and tetramethylrhodamine quencher (GeneScript, Piscataway, NJ), was mixed with 2 μL of extracted RNA. GAPDH primers (20 μmol/L) and probe (20 μmol/L) were also included. Each sample was run in duplicate. ZIKV RNA was reverse-transcribed for 10 minutes at 45°C, then heated to 95°C for 2 minutes. The PCR amplification cycles were 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 seconds and 60°C for 20 seconds. Standard curves of ZIKV RNA and GAPDH RNA were generated with serial dilutions of synthetic RNA (GeneScript) of the target sequence (accession number HQ234499.1). The thermocycler utilized was a Mic-2 qPCR (Bio Molecular Systems, Coomera, QLD, Australia). The relative number of ZIKV RNA was determined from the standard curve and was normalized with relative total RNA calculated from the GAPDH standard curve.

Results

Histopathologic Characterization of Acute ZIKV Infection in the Reproductive Tract

Testicle

Previous studies of ZIKV infection in mouse models have reported viral RNA in the testicle,26 and inflammation in association with virus at the terminal phase of disease has been observed.24, 35 However, histopathologic progression of reproductive diseases at early time points during acute ZIKV infection has not been studied. The histopathologic changes in the male reproductive tract at 5, 7, 9, 10, and 11 DPI in AG129 mice and at 5, 8, and 11 DPI in Ifnar−/− males were evaluated. Minimal inflammation was observed in the testicles of AG129 male mice at 5 DPI and was characterized by one or two foci of small aggregates of low numbers of neutrophils infiltrating the interstitium and encompassing <5% of the testicular space (Supplemental Table S1). The inflammatory cells were concentrated mainly around small- to medium-caliber blood vessels. At 7 DPI, mild increases in the numbers of neutrophils and size of aggregates infiltrating interstitial spaces were observed, but degenerative changes within the seminiferous tubules were not observed. At 9 DPI, mild interstitial cell hyperplasia was observed in 100% (5/5) of mice, and 40% (2/5) of animals showed mild tubular degeneration, with low numbers of individual spermatids undergoing necrosis within multifocal tubules (Figure 1B). One AG129 mouse had a severe necrotizing and hemorrhagic orchitis, with infiltration of large numbers of neutrophils into tubules, disruption of seminiferous tubular basement membranes, and expansion of the interstitium by hemorrhage, edema, and moderate numbers of neutrophils. Four AG129 mice were humanely euthanized at 10 DPI due to >20% weight loss, hyperexcitability when stimulated, intermittent hind limb paralysis, and a hunched stance when nonstimulated. Histopathologic evaluation of the testicle at this time (10 DPI) showed multifocal infiltration of numerous neutrophils forming sheets between tubules, and adjacent tubules showed variable degrees of tubular degeneration, with reduced spermatid numbers (mild) to entire tubular degeneration and necrosis (severe) noted. Similar histopathologic lesions were observed in the testicle at 11 DPI.

Ifnar−/− males never exhibited severe orchitis, which was observed in 36% (9/25) of AG129 mice over the course of the study (Figure 2). In the Ifnar−/− strain, the most severe inflammation observed in the testicle over the entire study was a moderate orchitis in one 3-week-old animal. Mild orchitis was observed in 67% (4/6) of 3-week-old mice during the terminal phase of disease (Supplemental Table S2) and was limited to interstitial lymphocytic and neutrophilic inflammation, with no observed tubular necrosis. Tubular necrosis was observed in only one mouse over the course of the study. Six-week-old Ifnar−/− males showed the least severe inflammation at 8 and 11 DPI, with 67% (4/6) of animals exhibiting no observable inflammation and 22% (2/6) exhibiting minimal interstitial neutrophil infiltration. Focal, minimal orchitis was observed in 67% (4/6) of 16-week-old Ifnar−/− mice at 8 and 11 DPI (Figure 1C).

Figure 2.

A and B: Histopathologic lesion severity in the reproductive tract of interferon type I and II receptor gene knockout (AG129) and interferon type I receptor gene knockout (Ifnar−/−) mice. AG129 mice exhibit increasing severity of orchitis (A) and epididymitis (B), with 100% exhibiting severe inflammation by 11 days after infection (DPI). C and D:Ifnar−/− mice exhibit an age-dependent disease phenotype, with 100% mortality in 3-week-old mice by 6 and 7 DPI, with 17% (n = 1) exhibiting moderate orchitis and severe epididymitis in 33% (n = 2) at the terminal phase of disease. C: In contrast, 6- and 16-week-old males exhibit no to mild orchitis at 5, 8, and 11 DPI. D: Epididymitis progresses from absent to mild at 5 DPI to minimal to moderate at 11 DPI in both 6- and 16-week-old Ifnar−/− mice. n = 5 (A and B); n = 6 (C and D).

Epididymis

In AG129 mice, mild epididymitis was observed at 5 DPI. Inflammation in AG129 mice progressed rapidly to moderate and severe epididymitis by 7 to 11 DPI (Figure 2). Early disease was characterized by multifocal aggregates of few neutrophils in the interstitial region. No tubular necrosis or degenerative changes were noted in the epididymis at 5 DPI. By 7 DPI, low numbers of tubules exhibited individual epithelial cell necrosis (Figure 1E). Necrosis of entire tubules was observed by 9 DPI. In all evaluated animals of both strains, the head of the epididymis was most severely affected, and tubular necrosis was limited to epithelial cells in the head of the epididymis.

Mild to marked epithelial regeneration, which was characterized by epithelial cell piling (up to three layers deep), the presence of short cuboidal epithelial cells, increased cytoplasmic basophilia, and marked karyomegaly, was observed concurrently with the epithelial cell necrosis in the epididymal ducts at 10 and 11 DPI in AG129 mice. Low numbers of degenerate spermatogonia were observed at 9 DPI, and moderate to marked numbers of both degenerate and viable spermatogonia were observed in epididymal tubules at 10 and 11 DPI in AG129 mice. The absence of mature spermatozoa and the presence of immature and degenerate mature spermatogonia within tubules were not parts of the inflammatory score, but occurred only in AG129 mice. Mice with moderate inflammation in the epididymis at 11 DPI had pronounced epithelial regeneration, which replaced the degenerate epithelial cells observed previously (<25% of epithelial cells).

Severe epididymitis was observed in both strains, but severe epididymitis in the Ifnar−/− strain was observed in only the youngest age group (3 weeks old) during the terminal phase of disease (6 and 7 DPI). Ifnar−/− male mice exhibited an age-dependent disease phenotype in the epididymis. At 5 DPI, 67% (2/3) of 3-week-old mice had no inflammation and 33% (1/3) of all three age groups exhibited mild epididymitis. The severity of inflammation increased dramatically at day 6 in these mice, with moderate to severe epididymitis characterized by tubular epithelial necrosis and infiltration by numerous neutrophils. The remaining weanling Ifnar−/− mice were humanely euthanized at 7 DPI, with 25% (1/4) exhibiting mild epididymitis, 50% (2/4) exhibiting moderate epididymitis, and 25% (1/4) exhibiting severe epididymitis. In 3-week-old Ifnar−/− males, maturing spermatids were not observed in epididymal tubules at any sacrifice time point, as is expected in weanling-age animals.

Six- and 16-week-old Ifnar−/− mice showed progressive epididymitis throughout the course of disease (Figure 2). Epididymitis was absent or minimal at 5 DPI in both age groups. Moderate epididymitis was observed in 67% (2/3) of 16-week-old Ifnar−/− mice at 8 DPI (Figure 1F) and in 67% (2/3) of 6-week-old Ifnar−/− mice at 11 DPI. Morphologically normal spermatids were observed within tubules at every sacrifice time point in 6- and 16-week-old Ifnar−/− mice.

Accessory Sex Glands

In AG129 mice, no significant histopathologic lesions were observed in evaluated sections of seminal vesicle (0/23), prostate (0/23), bulbourethral gland (0/9), or preputial gland (0/15) at 5, 7, 9, 10, or 11 DPI. Similarly, sections of testicle, epididymis, seminal vesicle, prostate, bulbourethral gland, and preputial gland were free of lesions in all sham-infected control AG129 mice (n = 8) at 5, 7, 9, 10, or 11 DPI.

Mild to marked neutrophilic and lymphocytic preputial adenitis was observed randomly in seven Ifnar−/− mice (Figure 3), affecting all age groups on various days of sacrifice. Mild neutrophilic prostatitis was observed in two Ifnar−/− mice (Figure 3), both of which were 16-week-old males sacrificed at 8 DPI. Mild to moderate necrotizing seminal vesiculitis was observed in all examined seminal vesicles of 3-week-old mice at 6 and 7 DPI.

Figure 3.

A: Interferon type I receptor gene knockout (Ifnar−/−) preputial gland, 8 days after infection (DPI). The periglandular adipose and interstitial tissue is infiltrated by low to moderate numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes (arrow). Preputial glands are composed of epithelial cells, which undergo holocrine secretion (arrowhead). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. B:Ifnar−/− ventral prostate, 8 DPI. The lamina propria underlying the prostatic epithelium is infiltrated by low to moderate numbers of neutrophils (arrow). Low numbers of prostatic epithelial cells are necrotic and slough into the prostatic lumen (arrowhead). The lumen contains moderate numbers of sperm (retrograde movement, handling artefact). H&E stain. C:Ifnar−/− vas deferens, 8 DPI. The entire vas deferens is lined by pseudociliated epithelial cells that show immunoreactivity for Zika virus antigen. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody; counterstain, hematoxylin. D:Ifnar−/− preputial gland, 8 DPI. Preputial gland epithelial cells show variable immunoreactivity to Zika virus antigen. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody; counterstain hematoxylin. E:Ifnar−/− ventral prostate, 8 DPI. Moderate numbers of prostatic epithelial cells and necrotic epithelial cells are immunoreactive to Zika virus antigen. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody; counterstain, hematoxylin. F:Ifnar−/− ampullary gland, 8 DPI. The ampullary gland (right) is an outpouching of the vas deferens (left) and is multifocally lined by epithelial cells that show immunoreactivity to Zika virus antibody. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody, counterstain, hematoxylin. All IHC images were pseudocolored utilizing Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) to convert the diaminobenzidine peroxidase brown chromogen to red to highlight the immunoreactivity to the hematoxylin counterstain. Original magnification: ×40 (A and B); ×20 (C–F). Scale bars: 50 μm (A and B); 100 μm (C–F).

IHC Analysis of Acute Infection in Male Reproductive Tissue

Virus location within the reproductive tract during acute infection was determined using immunofluorescence and IHC analysis. Infection in the testicle in the AG129 mouse initiated as infection of interstitial cells, noted with viral antigen detected at 5 DPI in AG129 mice, 6 DPI in 3-week-old Ifnar−/− mice, and 11 DPI in both 6- and 16-week-old Ifnar−/− males. At 9 DPI in AG129 mice, low numbers of Sertoli cells within few seminiferous tubules were positive for ZIKV, and testicular interstitial cells maintained ZIKV immunoreactivity. An increase in the number of ZIKV immunoreactive cells in both the interstitium and lining tubules was observed at 10 and 11 DPI (Figure 4) in AG129 males. Immunoreactivity was detected in testicular interstitial cells at least 4 days before the earliest observed infection in the seminiferous tubules of AG129 mice. Immunoreactivity of cells within the seminiferous tubules did not occur until after severe infection of the epididymis accompanied by sloughing of epithelial cells into the epididymal lumen. Immunoreactivity within seminiferous tubules was not detected in 6- and 16-week-old Ifnar−/− males. Immunoreactivity of the testicular interstitial cells and epididymal epithelial cells is associated with a rapid and severe inflammatory response.

Figure 4.

A: Interferon type I receptor gene knockout (Ifnar)−/− control testicle. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody, counterstain, hematoxylin. B: Interferon type I and II receptor gene knockout (AG129) testicle, 10 days after infection (DPI). Seminiferous tubules are lined by variable numbers of cells that exhibit immunoreactivity to Zika virus. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody, counterstain, hematoxylin. C:Ifnar−/− testicle, 11 DPI. Low numbers of seminiferous tubules are partially lined by cells that exhibit immunoreactivity to Zika virus antibody. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody; counterstain, hematoxylin. D:Ifnar−/− control epididymis. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody, counterstain, hematoxylin. E: AG129 epididymis, 5 DPI. Within the head of the epididymis, most tubules are lined by moderate numbers of epithelial cells that show immunoreactivity to Zika virus antibody. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody, counterstain, hematoxylin. F:Ifnar−/− epididymis, 11 DPI. Within the head of the epididymis, most tubules are lined by low to moderate numbers of epithelial cells that show immunoreactivity to Zika virus antibody. Polyclonal anti-Zika antibody; counterstain, hematoxylin. All IHC images were pseudocolored utilizing Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) to convert the diaminobenzidine peroxidase brown chromogen to red to highlight the immunoreactivity to the hematoxylin counterstain. Original magnification, ×20. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Viral antigen immunoreaction was observed in epididymal epithelial cells at all sacrifice time points in AG129 mice. Moderate numbers of epithelial cells were immunoreactive for ZIKV antigen at 5 and 7 DPI (Figure 4). Low numbers of tubules at 7, 9, 10, and 11 DPI were lined by >50% epithelial cells exhibiting immunoreactivity for ZIKV antigen. Viral antigen was present in low numbers of epithelial cells in the prostate and seminal vesicle at 7, 9, 10, and 11 DPI in AG129 males. No virus was detected within the cells of the bulbourethral gland or seminal vesicle at any time point in AG129 males.

In ZIKV-infected Ifnar−/− mice, viral antigen was not observed in the testicle by IHC at 5 DPI in any age group. Antigen immunoreactivity was observed in 3-week-old mice at 6 DPI in low numbers of interstitial cells, and in both interstitial and tubular cells at 7 DPI. The 6- and 16-week-old males did not show ZIKV immunoreactivity in the testicle until 11 DPI (Figure 4), and immunoreactivity was limited to Sertoli cells in low numbers of seminiferous tubules. Virus was detected in the epididymal tubular epithelial cells at 5 DPI in both the 3- and 6- week-old Ifnar−/− males, with multiple tubules having >50% of ZIKV-immunoreactive epithelial cells. ZIKV antigen persisted in the epididymal tubular epithelial cells of 3-week-old males and was present in mice that met early euthanasia criteria at 7 DPI. ZIKV antigen was first observed at 8 DPI in the 16-week-old males, and both the 6- and 16-week-old males had ZIKV antigen present in tubular epithelial cells at 11 DPI (Figure 4). Immunoreactivity was largely limited to epithelial cells in the head of the epididymis in all age groups of Ifnar−/− males at 5, 6, 7, 8, and 11 DPI. Viral antigen was observed in the apical portion of the cytoplasm in low numbers of prostatic epithelial cells (Figure 4) at 8 DPI in both 6- and 16-week-old males. Viral antigen was not detected in the bulbourethral gland or the seminal vesicles of any Ifnar−/− male at any time point.

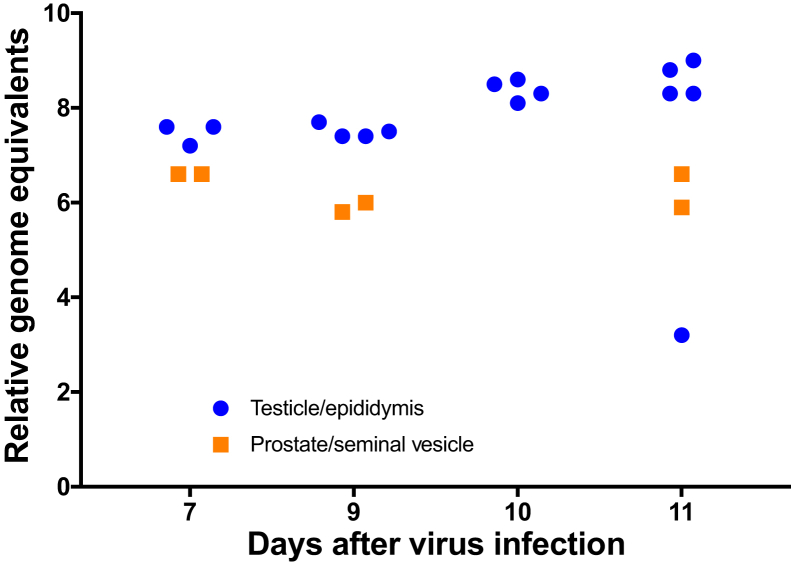

Detection of ZIKV RNA

Presence of ZIKV RNA was confirmed by RT-qPCR in the testicle and epididymis of AG129 mice at 7, 9, 10, and 11 DPI (Figure 5). In addition, ZIKV was detected in both the seminal vesicle and prostate (coagulating gland) of AG129 mice at 7, 9, and 11 DPI (Figure 5). Viral RNA was detected in the epididymis and testicle in all age groups of Ifnar−/− mice at 5, 8, and 11 DPI (Figure 6) as well as at early euthanasia time points (6 and 7 DPI) in 3-week-old Ifnar−/− males (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

ZIKV RNA in reproductive tissue in interferon type I and II receptor gene knockout (AG129) males. ZIKV RNA remains at relatively constant levels in both the epididymis and testicle of 6-week-old AG129 males from 7 to 11 days after infection (DPI). ZIKV is detectable by quantitative RT-PCR in pooled homogenates of the prostate and seminal vesicle from 7 to 11 DPI.

Figure 6.

A and B: ZIKV RNA in the reproductive tissue of interferon type I receptor gene knockout mice. ZIKV is detectable in both the testicle (A) and epididymis (B) of infected males at 5 to 11 days after infection. GE, genome equivalents.

Discussion

ZIKV is an emerging arbovirus of increasing importance due to an association with congenital defects as a result of in utero infection. This virus is known to infect the reproductive tissue of both males and females18, 36, 37, 38 and has been documented to persist in the reproductive tract of men for >60 days.15, 18, 39 However, it is currently unknown how ZIKV infection of the male reproductive tract impacts reproductive health in infected adult humans. Although infection of seminiferous tubules has been shown during the latter phase of infection, the route of transmission from the bloodstream to infection within seminiferous tubular cells has yet to be elucidated, and acute inflammation of the male reproductive tract has yet to be fully described, as early time points of infection have rarely been evaluated in any animal model.24, 25, 26 Additionally, detailed histopathologic phenotyping of acute ZIKV infection in all components of the male reproductive tract has not yet been reported. Herein, we provide such a characterization in two susceptible mouse strains that are commonly used for modeling ZIKV infection utilizing an epidemically relevant ZIKV strain.

Relative to AG129 males, Ifnar−/− males of all ages exhibited less severe reproductive disease phenotype between 5 and 11 DPI. Importantly, both 6- and 16-week-old Ifnar−/− males maintained production of maturing spermatids in the epididymal tubules during the entirety of infection, whereas AG129 males had no observable spermatids within tubules during the terminal stages of disease (10 and 11 DPI).

Here, we have identified that epithelial components of the male reproductive tract were the first cells to support ZIKV infection in both strains of mice. Infection of the epididymal tubular epithelial cells was the earliest and most robust infection within the male reproductive tract and was detectable by IHC as early as 5 DPI in both models. Infection of epididymal epithelial cells was followed by a marked inflammatory response with infiltration of moderate numbers to numerous neutrophils early in the course of disease in both mouse strains. An infiltration of lymphocytes was also observed as the disease progressed in the AG129 strain, but not in Ifnar−/− mice. ZIKV also infected nonepithelial cells of the male reproductive tract. The early and robust infection of epididymal epithelial cells, followed days later by infection of cells within the seminiferous tubules, suggests a retrograde infection moving from the epididymis distally into the seminiferous tubules rather than movement of virus from testicular interstitial cells across the blood–testis barrier.

Histologically observable disruption of tubular basement membranes by leukocytes was observed in only one (1/20) infected AG129 mouse and was not observed (0/27) in Ifnar−/− males. In this singular AG129 male, there was a severe, hemorrhagic, necrotizing, and neutrophilic orchitis, lesions not observed in any other infected animal. On IHC evaluation of the severely inflamed tissue, ZIKV antigen was detected in all evaluated portions of the testicle and epididymis of this severely affected mouse. Due to the singularity of this event, it is likely that severe interstitial inflammation disrupted the basement membranes of adjacent seminiferous tubules, resulting in tubular inflammation and ZIKV spread into the tubules.

Infection and severe inflammation in both the epididymis and testicle were multifocal and not widely distributed throughout the entire epididymis or testicle in both AG129 and Ifnar−/− mice. The highest numbers of ZIKV immunoreactive cells and most severe inflammation with epithelial cell necrosis were observed in the head of the epididymis, with only low numbers of immunoreactive cells and interstitial inflammation observed in the caput and tail of the epididymis throughout the course of the infection. These observations suggest a potential receptor difference between epithelial cells in various components of the reproductive tract, which may serve as a target for antiviral therapy. Infection and inflammation of the testicle were sporadic and did not concentrate well in one particular area. These findings are in contrast to those from previous models of testicular infection with ZIKV, in which severe orchitis was observed by 14 DPI, with a decrease in testicular mass.35 This difference may have been in part due to the previous study utilizing both African and Asian lineages, mouse-adapted ZIKV strains, or differences in infectious dose, as the previous report did not indicate the inoculation dose.35 It is also possible that the route of immunosuppression, the gene knockout in our current model compared with anti–IFN type I treatment in C57BL/6 mice in the study by Govero et al,35 may have played a role in the development of disease.

In addition to a robust infection observed in epididymal epithelial cells, and to a lesser extent, testicular interstitial cells, infection of epithelial cells in the prostate, seminal vesicles, and preputial gland was also observed as early as 5 DPI in AG129 mice and was also sporadically detected by IHC in Ifnar−/− mice in all age groups throughout infection. Previous modeling of ZIKV reproductive infection in Ifnar−/− males failed to reveal prostatitis or to highlight ZIKV antigen, utilizing a noncommercially available monoclonal antibody for IHC.40 This difference may have been due to strain variation, as the previously reported model utilized an Asian lineage Chinese ZIKV isolate from travelers visiting Fiji and Samoa rather than a contemporary isolate related to the outbreak in Brazil.40 Although ZIKV was not overtly observed on IHC evaluation of the AG129 model at 9, 10, and 11 DPI, ZIKV RNA was detectable by RT-qPCR in the prostate and seminal vesicles at these time points. This finding supports those from previous studies showing ZIKV replication in prostatic cell culture models.28

The low-level infection within the epithelial cells, accompanied by a lack of a severe inflammatory response, suggests that the accessory sex glands constitute a possible site of persistent viral infection within the male reproductive tract. All accessory sex glands provide cytoplasmic secretions to the ejaculate through either holocrine (bulbourethral gland) or apocrine (prostate and seminal vesicle) type secretion, and cytotoxicity would not need to occur for virus to be released into the ejaculate.

We hypothesize that sexual transmission occurs by one of the two routes: passage of cell-free virus shed into the ejaculate from accessory gland secretions, or passage of degenerate or necrotic epithelial cells sloughed into the epididymal lumen during active infection of the epididymal epithelial cells. As testicular contents are not actively included in the ejaculate, active replication in the testicle is of little consequence in sexual transmission until maturing spermatids are transferred from the testicle to the epididymis. The process of spermatid maturation in nondiseased mice requires approximately 35 days.41 In humans, the development of spermatozoa from spermatogonia takes 60 to 70 days, and maturation in the epididymis may take between 2 and 4 weeks.42 The combined spermatozoa development and epididymal maturation phase would result in a minimum of 75 days between direct infection of spermatogonia to ejaculation of infected spermatids under normal physiologic conditions. Sexual transmission from infected males to naïve females has been reported in AG129 mice as early as 7 DPI,43 which suggests that infection at alternative sites within the reproductive tract are crucial in the acute phase of disease. Case reports in humans have shown potential sexual transmission of ZIKV as rapidly as 4 days after the onset of clinical signs of systemic ZIKV in men.14 Additionally, at least one case of assumed sexual transmission in humans has involved an infected vasectomized male.44 Similarly, ZIKV sexual transmission has been shown in vasectomized mice.43 Significant ZIKV antigen was not detected within any cellular component of seminiferous tubules of either mouse model without a concurrent inflammatory response. Viral antigen observed in the current study only suggests that these epithelial cells are susceptible to ZIKV infection and does not prove a source of infectious virus or that these cell populations are permissive to ZIKV.

Some disease manifestations observed in the currently utilized immunocompromised mouse models are not likely to be directly applicable to human infection. For example, orchitis and epididymitis have been reported in several mouse models of ZIKV infection and were observed in both models utilized in this study. Orchitis and epididymitis cause abrupt and significant pain in humans,45 a clinical sign that has not yet been reported in case reports of ZIKV infection in men, thus supporting that significant orchitis is not present in humans. Additionally, the AG129 mouse model is a lethal model, as observed both in our study and previous reports.31 Cautious interpretation of the disease phenotype in mice and their application to human disease are warranted.

Additional research into the involvement of epididymal infection and accessory sex gland infection in the transmission of ZIKV is warranted. Standardization of animal models and use of clinically relevant, Western-hemisphere ZIKV isolates would be useful in facilitating the integration of data from multiple studies and in translation to clinical medicine. Morrison and Diamond46 briefly reviewed several mouse models and virus strains utilized to study manifestations of disease during ZIKV infection. Currently utilized methods of mouse model immunosuppression include IFN receptor gene knockout, as currently used in this study, dexamethasone suppression,47 and IFN receptor antibody treatment.48 Due to the more mild histopathologic lesions; the continued presence of maturing, viable spermatids in epididymal tubules throughout infection; and the ability to survive acute infection, the Ifnar−/− mouse is likely a superior model, relative to AG129 mice, for studying potential reproductive transmission of ZIKV using a clinically relevant Puerto Rican ZIKV isolate. Additionally, the Ifnar−/− mouse strain exhibits histopathologic lesions that are more likely to mimic male reproductive disease in humans. Additional research utilizing Ifnar−/− mice to differentiate and evaluate proposed routes of sexual transmission is needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kira Morgado for her diligence and expertise in tissue handling and slide preparation and Preston Collins for his assistance in IHC staining.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH/Public Health Service grant 5R33AI101483 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Virology Branch contract HHSN272201000039I/HHSN27200004 (J.D.M.).

C.S.C. and J.G.J. contributed equally to this work. A.J.V.W., V.S., and J.D.M. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.12.019.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Dick G.W. Zika virus (I). Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth A., Mercier A., Lepers C., Hoy D., Duituturaga S., Benyon E., Guillaumot L., Souarès Y. Concurrent outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus infections—an unprecedented epidemic wave of mosquito-borne viruses in the Pacific 2012-2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.41.20929. pii:20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heang V., Yasuda C.Y., Sovann L., Haddow A.D., da Rosa A.P.T., Tesh R.B., Kasper M.R. Zika virus infection, Cambodia, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:349–351. doi: 10.3201/eid1802.111224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy M.R., Chen T.H., Hancock W.T., Powers A.M., Kool J.L., Lanciotti R.S., Pretrick M., Marfel M., Holzbauer S., Dubray C., Guillaumot L., Griggs A., Bel M., Lambert A.J., Laven J., Kosoy O., Panella A., Biggerstaff B.J., Fischer M., Hayes E.B. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yockey L.J., Varela L., Rakib T., Khoury-Hanold W., Fink S.L., Stutz B., Szigeti-Buck K., Van den Pol A., Lindenbach B.D., Horvath T.L., Iwasaki A. Vaginal exposure to Zika virus during pregnancy leads to fetal brain infection. Cell. 2016;166:1247–1256.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson A., Slavinski S., Komoto K., Rakeman J., Weiss D. Suspected female-to-male sexual transmission of Zika virus—New York City, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:3–4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6528e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prisant N., Bujan L., Benichou H., Hayot P.-H., Pavili L., Lurel S., Herrmann C., Janky E., Joguet G. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira Melo A.S., Malinger G., Ximenes R., Szejnfeld P.O., Alves Sampaio S., Bispo De Filippis A.M. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:6–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tetro J.A. Zika and microcephaly: causation, correlation, or coincidence? Microbes Infect. 2016;18:167–168. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cugola F.R., Fernandes I.R., Russo F.B., Freitas B.C., Dias J.L., Guimarães K.P., Benazzato C., Almeida N., Pignatari G.C., Romero S., Polonio C.M., Cunha I., Freitas C.L., Brandão W.N., Rossato C., Andrade D.G., Faria Dde P., Garcez A.T., Buchpigel C.A., Braconi C.T., Mendes E., Sall A.A., Zanotto P.M., Peron J.P., Muotri A.R., Beltrão-Braga P.C. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature. 2016;534:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature18296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dick G.W. Zika virus (II). Pathogenicity and physical properties. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:521–534. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grard G., Caron M., Mombo I.M., Nkoghe D., Mboui Ondo S., Jiolle D., Fontenille D., Paupy C., Leroy E.M. Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa)–2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong P.S., Li M.Z., Chong C.S., Ng L.C., Tan C.H. Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse): a potential vector of Zika virus in Singapore. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Ortenzio E., Matheron S., de Lamballerie X., Hubert B., Piorkowski G., Maquart M., Descamps D., Damond F., Yazdanpanah Y., Leparc-Goffart I. Evidence of sexual transmission of Zika virus. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2195–2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1604449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musso D., Roche C., Robin E., Nhan T., Teissier A., Cao-Lormeau V.M. Potential sexual transmission of Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:359–361. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foy B.D., Kobylinski K.C., Foy J.L.C., Blitvich B.J., da Rosa A.T., Haddow A.D., Lanciotti R.S., Tesh R.B. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:880–882. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deckard D.T., Chung W.M., Brooks J.T., Smith J.C., Woldai S., Hennessey M., Kwit N., Mead P. Male-to-male sexual transmission of Zika virus—Texas, January 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:372–374. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkinson B., Hearn P., Afrough B., Lumley S., Carter D., Aarons E.J., Simpson A.J., Brooks T.J., Hewson R. Detection of Zika virus in semen. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:940. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.160107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamer D.H., Barbre K.A., Chen L.H., Grobusch M.P., Schlagenhauf P., Goorhuis A. Travel-associated Zika virus disease acquired in the Americas through February 2016: a GeoSentinel analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:99–108. doi: 10.7326/M16-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paz-Bailey G, Rosenberg ES, Doyle K, Munoz-Jordan J, Santiago GA, Klein L, Perez-Padilla J, Medina FA, Waterman SH, Gubern CG, Alvarado LI, Sharp TM: Persistence of Zika virus in body fluids—preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2017, [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1613108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Froeschl G., Huber K., von Sonnenburg F., Nothdurft H.D., Bretzel G., Hoelscher M., Zoeller L., Trottmann M., Pan-Montojo F., Dobler G., Woelfel S. Long-term kinetics of Zika virus RNA and antibodies in body fluids of a vasectomized traveller returning from Martinique: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:55. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2123-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoblaugh S., True L. Academic Press; 2012. Male reproductive system. Comparative Anatomy and Histology: A Mouse and Human Atlas; pp. 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maclachlan N.J., Dubovi E.J. Maclachlan N and Dubovi EJ. Elsevier; 2010. Fenner's Veterinary Virology, ed 4; pp. 467–481. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazear H.M., Govero J., Smith A.M., Platt D.J., Fernandez E., Miner J.J., Diamond M.S. A mouse model of Zika virus pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:720–730. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossi S.L., Tesh R.B., Azar S.R., Muruato A.E., Hanley K.A., Auguste A.J., Langsjoen R.M., Paessler S., Vasilakis N., Weaver S.C. Characterization of a novel murine model to study Zika virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:1362–1369. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Julander J.G., Siddharthan V., Evans J., Taylor R., Tolbert K., Apuli C., Stewart J., Collins P., Gebre M., Neilson S., Van Wettere A., Lee Y.M., Sheridan W.P., Morrey J.D., Babu Y.S. Efficacy of the broad-spectrum antiviral compound BCX4430 against Zika virus in cell culture and in a mouse model. Antiviral Res. 2017;137:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawiecki A.B., Mayton E.H., Dutuze M.F., Goupil B.A., Langohr I.M., Del Piero F., Christofferson R.C. Tissue tropisms, infection kinetics, histologic lesions, and antibody response of the MR766 strain of Zika virus in a murine model. Virol J. 2017;14:82. doi: 10.1186/s12985-017-0749-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan J.F., Yip C.C., Tsang J.O., Tee K.M., Cai J.P., Chik K.K., Zhu Z., Chan C.C., Choi G.K., Sridhar S., Zhang A.J., Lu G., Chiu K., Lo A.C., Tsao S.W., Kok K.H., Jin D.Y., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Differential cell line susceptibility to the emerging Zika virus: implications for disease pathogenesis, non-vector-borne human transmission and animal reservoirs. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e93. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Broek M.F., Müller U., Huang S., Aguet M., Zinkernagel R.M. Antiviral defense in mice lacking both alpha/beta and gamma interferon receptors. J Virol. 1995;69:4792–4796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4792-4796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller U., Steinhoff U., Reis L.F., Hemmi S., Pavlovic J., Zinkernagel R.M., Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aliota M.T., Caine E.A., Walker E.C., Larkin K.E., Camacho E., Osorio J.E. Characterization of lethal Zika virus infection in AG129 mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. National Research Council: Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suwa T., Nyska A., Haseman J.K., Mahler J.F., Maronpot R.R. Spontaneous lesions in control B6C3F1 mice and recommended sectioning of male accessory sex organs. Toxicol Pathol. 2016;30:228–234. doi: 10.1080/019262302753559560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann P.C., Vahle J., Keenan C.M., Baker J.F., Bradley A.E., Goodman D.G., Harada T., Herbert R., Kaufmann W., Kellner R., Nolte T., Rittinghausen S., Tanaka T. International harmonization of toxicologic pathology nomenclature: an overview and review of basic principles. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:7S–13S. doi: 10.1177/0192623312438738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Govero J., Esakky P., Scheaffer S.M., Fernandez E., Drury A., Platt D.J., Gorman M.J., Richner J.M., Caine E.A., Salazar V., Moley K.H., Diamond M.S. Zika virus infection damages the testes in mice. Nature. 2016;540:438–442. doi: 10.1038/nature20556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gornet M.E., Bracero N.J., Segars J.H. Zika virus in semen: what we know and what we need to know. Semin Reprod Med. 2016;34:285–292. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1592312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansuy J.M., Suberbielle E., Chapuy-Regaud S., Mengelle C., Bujan L., Marchou B., Delobel P., Gonzalez-Dunia D., Malnou C.E., Izopet J., Martin-Blondel G. Zika virus in semen and spermatozoa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1106–1107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30336-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansuy J.M., Dutertre M., Mengelle C., Fourcade C., Marchou B., Delobel P., Izopet J., Martin-Blondel G. Zika virus: high infectious viral load in semen, a new sexually transmitted pathogen? Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:405. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicastri E., Castilletti C., Liuzzi G., Iannetta M., Capobianchi M.R., Ippolito G. Persistent detection of Zika virus RNA in semen for six months after symptom onset in a traveller returning from Haiti to Italy, February 2016. Euro Surveill. 2016;21:1–4. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.32.30314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma W., Li S., Ma S., Jia L., Zhang F., Zhang Y., Zhang J., Wong G., Zhang S., Lu X., Liu M., Yan J., Li W., Qin C., Han D., Qin C., Wang N., Li X., Gao G.F. Zika virus causes testis damage and leads to male infertility in mice. Cell. 2016;167:1511–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.016. Erratum in: Cell, 2017, 168:542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oakberg E.F. Duration of spermatogenesis in the mouse. Nature. 1957;180:1137–1138. doi: 10.1038/1801137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White B.A. ed 6. Elsevier; 2010. Berne & Levy Physiology; pp. 758–798. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duggal N.K., Ritter J.M., Pestorius S.E., Zaki S.R., Davis B.S., Chang G.J., Bowen R.A., Brault A.C. Frequent Zika virus sexual transmission and prolonged viral RNA shedding in an immunodeficient mouse model. Cell Rep. 2017;18:1751–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arsuaga M., Bujalance S.G., Díaz-Menéndez M., Vázquez A., Arribas J.R. Probable sexual transmission of Zika virus from a vasectomised man. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trojian T.H., Lishnak T.S., Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:583–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrison T.E., Diamond M.S. Animal models of Zika virus infection, pathogenesis, and immunity. J Virol. 2017;91:e00009–e00017. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00009-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan J.F., Zhang A.J., Chan C.C., Yip C.C., Mak W.W., Zhu H., Poon V.K., Tee K.M., Zhu Z., Cai J.P., Tsang J.O., Chik K.K., Yin F., Chan K.H., Kok K.H., Jin D.Y., Au-Yeung R.K., Yuen K.Y. Zika virus infection in dexamethasone-immunosuppressed mice demonstrating disseminated infection with multi-organ involvement including orchitis effectively treated by recombinant type I interferons. EBioMedicine. 2016;14:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith D.R., Hollidge B., Daye S., Zeng X., Blancett C., Kuszpit K., Bocan T., Koehler J.W., Coyne S., Minogue T., Kenny T., Chi X., Yim S., Miller L., Schmaljohn C., Bavari S., Golden J.W. Neuropathogenesis of Zika virus in a highly susceptible immunocompetent mouse model after antibody blockade of type I interferon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.