Summary

Thyrotoxicosis is associated with cardiac dysfunction; more commonly, left ventricular dysfunction. However, in recent years, there have been more cases reported on right ventricular dysfunction, often associated with pulmonary hypertension in patients with thyrotoxicosis. Three cases of thyrotoxicosis associated with right ventricular dysfunction were presented. A total of 25 other cases of thyrotoxicosis associated with right ventricular dysfunction published from 1994 to 2017 were reviewed along with the present 3 cases. The mean age was 45 years. Most (82%) of the cases were newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis. There was a preponderance of female gender (71%) and Graves’ disease (86%) as the underlying aetiology. Common presenting features included dyspnoea, fatigue and ankle oedema. Atrial fibrillation was reported in 50% of the cases. The echocardiography for almost all cases revealed dilated right atrial and or ventricular chambers with elevated pulmonary artery pressure. The abnormal echocardiographic parameters were resolved in most cases after rendering the patients euthyroid. Right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension are not well-recognized complications of thyrotoxicosis. They are life-threatening conditions that can be reversed with early recognition and treatment of thyrotoxicosis. Signs and symptoms of right ventricular dysfunction should be sought in all patients with newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis, and prompt restoration of euthyroidism is warranted in affected patients before the development of overt right heart failure.

Learning points:

Thyrotoxicosis is associated with right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension apart from left ventricular dysfunction described in typical thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy.

Symptoms and signs of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension should be sought in all patients with newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis.

Thyrotoxicosis should be considered in all cases of right ventricular dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension not readily explained by other causes.

Prompt restoration of euthyroidism is warranted in patients with thyrotoxicosis complicated by right ventricular dysfunction with or without pulmonary hypertension to allow timely resolution of the abnormal cardiac parameters before development of overt right heart failure.

Background

Thyrotoxicosis is associated with cardiac dysfunction, more commonly, left ventricular dysfunction secondary to the chronic effect of thyroid hormones on the myocardium and haemodynamic circulation in long-standing thyrotoxicosis. In recent years, cases of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension associated with thyrotoxicosis have been reported. However, the mechanisms involved remain unclear. We present three cases of thyrotoxicosis associated with right ventricular dysfunction. A total of 25 other cases of thyrotoxicosis associated with right ventricular dysfunction published from 1994 to 2017 were reviewed along with the present 3 cases to establish the common clinical features, echocardiographic parameters and its clinical course.

Case presentation, management and outcome

Case 1

A 25-year-old woman presented with fever, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and vomiting for 2 days associated with a 2-month history of palpitation, heat intolerance, weight loss and reduced effort tolerance. On examination, she was febrile with a heart rate of 104 beats per minute and oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. She had exophthalmos and a diffuse goitre. Jugular venous pressure (JVP) was raised with C–V wave. There was also a systolic murmur over the left sternal edge and a pulsatile hepatomegaly. There were no clinical findings to suggest an underlying connective tissue disease, chronic pulmonary or thromboembolic disorders. She was diagnosed with Graves’ disease and was commenced on carbimazole and propanolol. Free thyroxine (FT4) level was 75.5 pmol/L (normal range 11.8–23.2 pmol/L) and thyrotropin (TSH) level was <0.01 mU/L (normal range 0.35–5.50 mU/L). Echocardiography revealed an enlarged right ventricle with mild pulmonary and tricuspid regurgitation. The systolic pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) was 47 mmHg (normal range 15–30 mmHg) (Fig. 1). The FT4 level improved to 35.1 pmol/L at two-month and 14.2 pmol/L at four-month along with symptoms resolution. An echocardiography repeated five months after restoration of euthyroidism showed a normalized systolic PAP of 24 mmHg with normal chamber sizes.

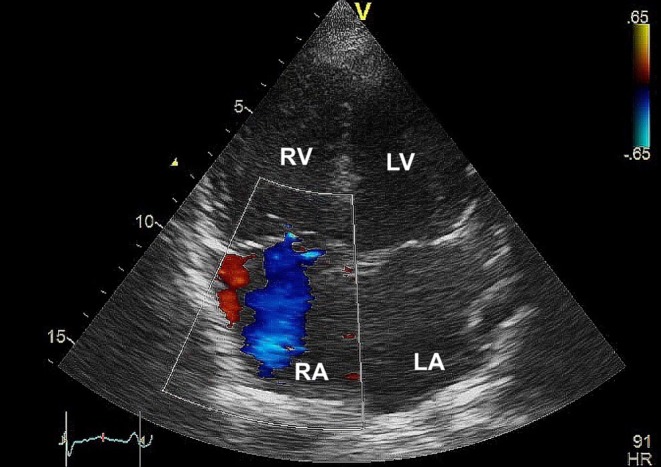

Figure 1.

A transthoracic apical four-chamber view of Case 1 demonstrating an enlarged right ventricle with tricuspid regurgitation.

Case 2

A 47-year-old woman presented with an acute abdomen. She defaulted her anti-thyroid medication shortly after being diagnosed with Graves’ disease two months earlier. On examination, she was thyrotoxic clinically with a heart rate of 100 beats per minute. Other positive physical findings included a systolic murmur over the left sternal edge, rebound tenderness over the right iliac fossa and bilateral pedal oedema. There were no clinical findings to suggest an underlying connective tissue disease, chronic pulmonary or thromboembolic disorders. She was diagnosed with acute appendicitis with impending thyroid storm. High-dose propylthiouracil, propranolol, Lugol’s iodine and hydrocortisone were administered. FT4 level was 101 pmol/L and TSH was <0.01 mU/L. Laparotomy confirmed a perforated appendix. Echocardiography revealed dilated left and right atria, mild tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitation with a systolic PAP of 50 mmHg. All the thyrotoxic symptoms and signs with pedal oedema resolved promptly upon institution of anti-thyroid therapy. Post-operative recovery was uneventful. She was planned for radioactive iodine treatment and a repeat echocardiography. Unfortunately, she was lost to follow-up.

Case 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with three-day history of fever preceded by one-week history of cough and diarrhoea associated with palpitation, weight loss, hand tremors and dyspnoea. She was previously diagnosed with toxic multinodular goitre at the age of 25 years. She refused radioactive iodine and defaulted treatment in the past three years. On examination, she had atrial fibrillation with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute. There was a multinodular goitre, a systolic murmur over the left sternal edge, a right pleural effusion and bilateral pedal oedema. She was diagnosed with impending thyroid storm precipitated by pneumonia and was commenced on high-dose propylthiouracil, propranolol, hydrocortisone and Lugol’s iodine along with a broad spectrum antibiotic. Her FT4 level was 47.7 pmol/L and TSH was <0.01 mU/L. She decompensated within 12 h after admission and went into pulseless electrical activity requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation before a return of spontaneous circulation. Echocardiography performed at four hours after resuscitation revealed dilated right atrium and ventricle, moderate tricuspid regurgitation with a systolic PAP of 65 mmHg. There was no thrombus or vegetation. Left ventricular ejection fraction was also impaired at 35%. A computed tomography angiogram of the pulmonary artery showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism. Unfortunately, her illness was further complicated by a right temporoparietal infarct with haemorrhagic transformation associated with multi-organ failure and she succumbed nine days after admission.

Discussion

The effect of thyroid hormone on the cardiovascular system was first described centuries ago (1). Thyrotoxicosis is known to aggravate pre-existing cardiac disease or may in itself results in thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy. This is due to an increased cardiac output state induced by thyrotoxicosis (2). The inotropic and chronotropic effect of thyroid hormones on the heart coupled with decreased systemic vascular resistance leads to a hyperdynamic circulation with an increased cardiac output. These hemodynamic changes will lead to a state of high-output cardiac failure involving both left and right ventricles often seen in the older patients with long-standing thyrotoxicosis. In recent years, there has been an increase in reports of thyrotoxicosis associated with isolated right ventricular dysfunction, frequently associated with pulmonary hypertension along with variable degree of right heart failure.

A compilation of 25 reported cases of thyrotoxicosis associated with right ventricular dysfunction from 1994 to 2017 along with the present three cases was performed (Table 1). There was a female preponderance (71%) with a mean age of 45 years (range: 25–71). Most of them (82%) were newly diagnosed with thyrotoxicosis. Graves’ disease was the most commonly (86%) reported aetiology. Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of pulmonary hypertension among patients with thyrotoxicosis ranged from 35% to 65% (24, 25, 26, 27). Significant correlations between TSH and FT4 levels with PAP have been reported (23). Although up to 49% of patients with primary pulmonary hypertension have been found to be associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, it is unclear if this association is independent (28).

Table 1.

Demographics, cardiac manifestations, echocardiographic findings, treatment and outcomes of 28 patients with thyrotoxicosis associated with right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension.

| Reference | Age (years) | Gender | Diagnosis | Cardiac manifestations | ECG | Echocardiographic findings | Parameters used to estimate PAP | Pre-treatment PAP (mmHg) | Post-treatment PAP (mmHg) | Treatment | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR1 | 25 | F | Graves’ | Reduced effort tolerance, raised JVP, LSE systolic murmur, pulsatile hepatomegaly | SR | Dilated RV, mild TR/PR | sPAP | 47 | 24 | Carbimazole, beta blocker | Euthyroid restored at 4-month, RV dysfunction reversed at 9 months |

| CR2 | 47 | F | Graves’ | Pedal oedema, systolic murmur at LSE | SR | Dilated RA/LA | sPAP | 50 | NA | PTU, beta blocker | Defaulted follow-up and planned RAI treatment |

| CR3 | 45 | F | Toxic MNG | Pedal oedema, systolic murmur, pleural effusion | AF | Dilated RA/RV, moderate TR, EF 35% | sPAP | 65 | NA | PTU, beta blocker, hydrocortisone, diuretic, mechanical ventilation | Died at day 9 from haemorrhagic stroke |

| (3) | 47 | M | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema | SR | Dilated RA/RV, severe TR | PAP (systolic/diastolic) | 45/18* | NR | PTU, beta blocker, diuretics, tricuspid valve repair | Right heart failure resolved clinically |

| (4) | 41 | M | Graves’ | Dyspnoea | NR | Dilated RA/RV/LA | sPAP | 57 | 36 | PTU, beta blocker, RAI | Euthyroidism restored at 2 years, dilatation of RA/RV resolved at 2 years 9 months |

| (4) | 68 | M | Graves’ | Dyspnoea | NR | Dilated RA/RV | sPAP | 52 | 32 | Methimazole, RAI | Dilatation of RA/RV resolved at 2 years |

| (4) | 59 | M | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, RV heave | AF | Dilated RA/RV, severe TR | sPAP | 51 | 34 | PTU, beta blocker, digoxin, anticoagulation, RAI | AF reverted to SR, dilatation of RA/RV resolved at 2 years |

| (5) | 43 | F | NR | Pedal oedema, raised JVP, parasternal heave, LSE systolic murmur | NR | Dilated RA, moderate-severe TR | RVSP | 46 | NR | PTU, beta blocker, diuretic, RAI | RA dilatation and TR resolved at 3 months |

| (6) | 71 | F | NR | Dyspnoea, raised JVP, LSE systolic murmur | AF | Dilated RA, severe TR | RVSP | 65 | Normal | Methimazole, beta blocker, diuretic, digoxin | AF reverted to SR, dilatation of RA/RV and TR resolved |

| (7) | 38 | F | Graves’ | Pedal oedema, raised JVP, ascites, hepatomegaly | AF | Dilated RV, moderate TR | sPAP | 70 | 48 | PTU, beta blocker, dexamethasone, diuretic | RA dilatation and TR resolved at 2 weeks |

| (8) | 56 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, raised JVP, PSM at LSE | AF | Dilated RA/RV | sPAP | 75 | 45 | Diltiazem, anticoagulation, methimazole | AF reverted to SR, dilatation of RV resolved after a few weeks |

| (9) | 54 | F | Radiation fall-out | Dyspnoea, oedema, bilateral pleural effusion | AF | Dilated RV, severe TR | NR | Normal | Normal | Methimazole, beta blocker, diuretic, anticoagulation | AF reverted to SR at 48-h, other cardiac parameters normalized at 6 weeks |

| (10) | 45 | M | NR | Pedal oedema, raised JVP | AF | Dilated RV, severe TR | RVSP | 26 | 22 | Carbimazole, beta blocker, diuretic | AF reverted to SR at 1-week, euthyroidism restored in 1 month, ECHO at 5 months showed mildly dilated RV with mild TR |

| (10) | 34 | F | NR | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, PSM at LSE | AF | Dilated RV, moderate TR | RVSP | 69 | 59 | PTU, diuretic, non-invasive ventilation | Euthyroidism restored at 6 weeks but RV remains dilated with moderate TR. Patient declined definitive treatment and remained in AF at 3 years |

| (11) | 48 | F | MNG | Fatigue, anarsarca, distended JVP, apical systolic murmur | AF | Dilated LA, severe TR | sPAP | 40 | Normal | Carbimazole, beta blocker, diuretics, digoxin, anticoagulation | AF reverted to SR at day 4, other cardiac parameters normalized at 4 months |

| (12) | 43 | F | Graves’ | Fatigue, pedal oedema, raised JVP, LSE systolic murmur | SR | Dilated RV, moderate TR | sPAP | 70 | 30 | Carbimazole, diuretics | Euthyroidism restored at 4 months, right heart failure and PAP normalized at 14 months |

| (13) | 36 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, fatigue, pedal oedema, distended JVP, LSE systolic murmur, pleural effusion, ascites, hepatomegaly | AF | Dilated RA/RV, moderate TR | sPAP | 55 | Normal | PTU, beta blocker, diuretic, anticoagulation | AF reverted to SR and euthyroid restored at 2 months, other cardiac parameters normalized at 3 months |

| (14) | 42 | M | Graves’ | Pleuritic chest pain | RBBB | Dilated RV with hypokinesia | mPAP | 27* | NR | Methimazole, beta blocker, prednisolone | NR |

| (15) | 34 | F | NR | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, raised JVP, RV heave, LSE systolic murmur, ascites, hepatomegaly | AF | Dilated RV | sPAP | 45 | Normal | Methimazole, beta blocker, diuretic | Euthyroidism restored at 1 month, AF and ECHO abnormalities resolved at 10 months |

| (16) | 46 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema | AF | Dilated RA/RV | mPAP | 53* | 15* | PTU, beta blocker, diuretic, anticoagulation, RAI | Euthyroidism restored and PAP normalized at 7 months |

| (17) | 47 | F | NR | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, apical systolic murmur, ascites | AF | TR | sPAP | 45 | NR | PTU, beta blocker, diuretic | Right heart failure relapsed due to non-compliance to PTU, resolved with PTU reinstitution |

| (17) | 42 | F | Graves’ | Anarsarca, apical systolic murmur | AF | Dilated RA/RV, moderate TR/MR | sPAP | 60 | 22 | PTU, beta blocker, diuretic | Anasarca resolved. Remained well at 4 years |

| (18) | 29 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, distended JVP, RV heave, PSM at LSE | SR | Dilated RA/RV, severe TR | sPAP | 51 | Normal | PTU, diuretic, Subtotal thyroidectomy | Euthyroidism restored at 3 months, ECHO abnormalities resolved |

| (19) | 53 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, distended JVP | SR | Dilated RA/LA, mild-moderate TR | mPAP | 44* | 39 (RVSP) | PTU, beta blocker, diuretic | Euthyroidism restored at 4 months, ECHO showed resolved LA/RA dilatation with trivial TR |

| (20) | 45 | M | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, raised JVP, RV heave, loud P2 | Partial RBBB | Dilated RA/RV/LA, severe TR, moderate MR | sPAP | 78 | 45 | Carbimazole, RAI | Euthyroidism restored within a few weeks, ECHO showed normal sized chambers with trivial TR |

| (21) | 35 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, LSE murmur | SR | TR | RVSP | 60 | 35 | Methimazole, RAI | PAP normalized after more than 10 weeks |

| (22) | 32 | M | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, pedal oedema, loud P2 | Partial RBBB | Dilated RV, severe TR | mPAP | 27* | NR | Methimazole, diuretic | TR resolved upon methimazole dose escalation, RV dilatation improved |

| (23) | 48 | F | Graves’ | Dyspnoea, raised JVP, PSM over tricuspid area, pleural effusion | SR | Moderate TR | sPAP | 65 | Normal | Carbimazole, RAI | Euthyroidism restored at 6 months. TR and pulmonary hypertension resolved at 8 months |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CR, case report; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECHO, echocardiogram; F, female; JVP, jugular venous pressure; LA, left atrium; LSE, left sternal edge; M, male; MNG, multinodular goitre; mPAP, mean PAP; MR, moderate regurgitation; ND, not done; NR, not reported; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PR, pulmonary regurgitation; PSM, pan systolic murmur; PTU, propylthiouracil; RA, right atrium; RAI, radioactive iodine; RV, right ventricle; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; sPAP, systolic PAP; SR, sinus rhythm; TR, tricuspid regurgitation. Normal range for sPAP: ≥30 mmHg; PAP (systolic/diastolic): ≤ 24/6-12 mmHg; mPAP: 10-18 mmHg; RVSP: ≤ 40 mmHg. * denotes value derived from right heart catheterization.

The common cardiac manifestations in the present case series included dyspnoea, fatigue and lower limb oedema. Thyrotoxic symptoms were only present in 68% of the cases. 22 cases (79%) had overt right heart failure clinically. Cardiovascular examination often revealed systolic murmur of tricuspid regurgitation and raised JVP. Atrial fibrillation was present in 50% of the cases. Although there were concomitant acute appendicitis in Case 2 and pneumonia in Case 3 upon presentation, the probability of either condition to be the direct cause of the RV dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension is low in view of the acute nature of these concomitant illnesses.

The echocardiography for all cases revealed features of right ventricular dysfunction including dilated right atrial or right ventricular chambers and or tricuspid regurgitation. Left ventricular function was preserved in all except for one. The measured PAP was consistent with pulmonary hypertension in all but two cases (93%) with systolic PAP >30 mmHg, mean PAP >25 mmHg or right ventricular systolic pressure >40 mmHg. Five patients underwent right heart catheterisation and all had confirmed pulmonary hypertension. All patients except Case 3 had prompt resolution of symptoms and signs of right ventricular dysfunction upon treatment initiation for thyrotoxicosis, of the 23 cases with echocardiography repeated after euthyroidism was restored, the features of right ventricular dysfunction resolved completely in 21 cases. Post-treatment PAP was reported in 21 cases, two-third had complete normalization of PAP while one-third had its PAP improved significantly close to the normal range.

There are several postulated mechanisms for the development of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension in thyrotoxicosis. The increased blood volume caused by the activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in hyperthyroidism coupled with reduced peripheral vascular resistance increases the right ventricular preload and thus the cardiac output (29). The high cardiac output increases the pulmonary vasculature endothelial sheer stress causing endothelial injury. This sheer stress stimulates the pulmonary vascular smooth muscle, which then enhances intra-cytoplasmic calcium concentration that induces vasoconstriction of pulmonary vascular beds. These mechanisms consequently increase pulmonary arterial pressure and induce right ventricular dysfunction (30).

Another less established hypothesis is the direct effect of excess thyroid hormones inducing metabolism of intrinsic pulmonary vasodilating substances resulting in pulmonary vasoconstriction and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (16). The pulmonary vasculature changes contribute to the haemodynamic burden of the right ventricle on top of the increased venous return that accompanies the uncontrolled hyperthyroid state (18).

The autoimmune nature of Graves’ disease is believed to induce an immune mediated pulmonary endothelial damage. However, studies examining the relationship between the autoimmunity in Graves’ disease and pulmonary hypertension have produced conflicting results. Zuhur et al. demonstrated the presence of pulmonary hypertension in a significant proportion of patients with hyperthyroidism but did not find any difference of its prevalence between patients with Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goitre (35% vs 36%) (27). There was also no association found between pulmonary hypertension with TSH receptor antibodies although a positive correlation was found in another smaller study (26).

The occurrence of right ventricular dysfunction is independent from the presence or absence of left ventricular dysfunction. There was only one case in the present series reported to have concomitant left ventricular dysfunction. This finding is consistent with the findings from Hong et al., which demonstrated that the right ventricular dysfunction in thyrotoxicosis is not secondary to hemodynamic changes induced by thyrotoxicosis-associated left ventricular dysfunction (31). A longitudinal study on patients with Graves’ thyrotoxicosis also demonstrated evidence of hyperdynamic right ventricular function, which normalized after resolution of thyrotoxicosis with treatment (29). It was thus postulated that an elevated right ventricular preload will predispose one to decompensated right ventricular failure if not reversed promptly.

The present case series is the largest so far, which provide an overview of this often less recognized association. Limitations include the lack of objectivity in the evaluation of right ventricular dysfunction and only five patients had their pulmonary hypertension confirmed with direct PAP measurements via right heart catheterisation. The exact duration required from restoration of euthyroidism to normalization of abnormal cardiac parameters were not specified in many cases. The clinical dilemma often lies in the extent of investigations these patients should be subjected to in order to exclude other causes of isolated right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Further research on the potential mechanism of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction in thyrotoxicosis, predisposing factors and natural history will be essential to provide a rational approach in the detection, prevention and management strategy of this condition.

In conclusion, right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension is not well recognized, potentially lethal but fully reversible complication of thyrotoxicosis. It appeared to be predominantly driven by the increased cardiac output and pulmonary vascular resistance. It may be underdiagnosed due to the non-specific symptoms of dyspnoea or fatigue that is often attributable to the thyrotoxicosis itself. Based on the findings from the present case series, the sign and symptoms of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension should be actively sought in all cases of thyrotoxicosis regardless of aetiology, especially among those with newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis. Among patients with unexplained right ventricular dysfunction and or pulmonary hypertension, one should consider screening for hyperthyroidism. As the right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension are fully reversible, prompt restoration of euthyroidism is warranted to prevent the development of decompensated right heart failure and to prevent recurrence of right ventricular dysfunction and or pulmonary hypertension. Definitive treatment options, such as radioactive iodine therapy or thyroidectomy, should be considered early to allow timely resolution of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was registered with the National Medical Research, Malaysia (Research ID: 35825).

Patient consent

A written informed consent has been obtained from the patients or guardians for publication of the submitted article and accompanying image.

Author contribution statement

Carolina Shalini Singarayar was the endocrine fellow in-charge for Cases 1 and 2; prepared the manuscript and reviewed the literature. Foo Siew Hui was the consultant endocrinologist in-charge of Cases 1, 2 and 3; reviewed the literature and edited the manuscript. Nicholas Cheong and Goay Swee En were the medical officers in-charge of Cases 2 and 3 respectively; assisted in the compilation of the case reports and production of the echocardiographic image.

References

- 1.Legge IE. Parry and Parry’s disease. Res Medica 1961. 2 33–37. ( 10.2218/resmedica.v2i4.363) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desforges JF, Woeber KA. Thyrotoxicosis and the heart. New England Journal of Medicine 1992. 327 94–98. ( 10.1056/NEJM199207093270206) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xenopoulos NP, Braden GA, Applegate RJ. Severe right heart failure in a patient with Graves’ disease. Clinical Cardiology 1996. 19 903–905. ( 10.1002/clc.4960191113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soroush-Yari A, Burstein S, Hoo GWS, Santiago SM. Pulmonary hypertension in men with thyrotoxicosis. Respiration 2005. 72 90–94. ( 10.1159/000083408) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitner TE, Hudson CJ, Smith TD, Littmann L. Hyperthyroidism: presenting as isolated tricuspid regurgitation and right heart failure. Texas Heart Institute Journal 2005. 32 244–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park J-H, Shong M, Lee J-H, Choi SW, Jeong JO, Seong I-W. Reversible severe tricuspid regurgitation with right heart failure associated with thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 2006. 16 813–814. ( 10.1089/thy.2006.16.813) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paran Y, Nimrod A, Goldin Y, Justo D. Pulmonary hypertension and predominant right heart failure in thyrotoxicosis. Resuscitation 2006. 69 339–341. ( 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail HM. Reversible pulmonary hypertension and isolated right-sided heart failure associated with hyperthyroidism. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2007. 22 148–150. ( 10.1007/s11606-006-0032-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovambattista RD. Hyperthyroidism as a reversible cause of right ventricular overload and congestive heart failure. Cardiovascular Ultrasound 2008. 6 29 ( 10.1186/1476-7120-6-29) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tam VH, Fung LM. Severe right heart failure in two patients with thyrotoxicosis. Hong Kong Medical Journal 2008. 14 321–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syriou V, Plastiras SC, Paterakis T, Moyssakis I, Vlachoyiannopoulos P. Severe reversible right heart failure in a patient with hyperthyroidism. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2008. 62 334–336. ( 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00979.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegazi MO, Sayed AE, Ghoussein HE. Pulmonary hypertension responding to hyperthyroidism treatment. Respirology 2008. 13 923–925. ( 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01353.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanović B, Tadić M, Simić D. Isolated right-sided heart failure in a patient with hyperthyroidism. Acta Clinica Croatica 2011. 50 599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonough RJ, Moul MS, Beckman D, Slim AM. Isolated right ventricular failure in hyperthyroidism: a clinical dilemma. Heart International 2011. 6 e11 ( 10.4081/hi.2011.e11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonou M, Lampropoulos KM, Andriopoulou M, Kotsas D, Lakoumentas J, Barbetseas J. Severe tricuspid regurgitation and isolated right heart failure due to thyrotoxicosis. Indian Heart Journal 2012. 64 600–602. ( 10.1016/j.ihj.2012.09.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakchbandi IA, Wirth JA, Inzucchi SE. Pulmonary hypertension caused by Graves’ thyrotoxicosis. Chest 1999. 116 1483–1485. ( 10.1378/chest.116.5.1483) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J, Schattner A. Right heart failure and hyperthyroidism: a neglected presentation. American Journal of Medicine 2003. 115 76–77. ( 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00288-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lozano HF, Sharma CN. Reversible pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid regurgitation and right-sided heart failure associated with hyperthyroidism. Cardiology in Review 2004. 12 299–305. ( 10.1097/01.crd.0000137259.83169.e3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang HL, Chen LC, Ko WC. Hyperthyroidism presenting with severe pulmonary hypertension: a case report and literature review. Journal of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine 2010. 21 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan F, Mukherji A, Nabar S, Ashwini G. Graves disease presenting as right heart failure with severe pulmonary hypertension. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2016. 3636–3639. ( 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20162345) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rashidi F, Sate H, Faraji E, Tahsini Tekantapeh S. Thyrotoxicosis presenting as exertional dyspnea and pulmonary hypertension: case report and review of literature. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports 2017. 5 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okura H, Takatsu Y. High-output heart failure as a cause of pulmonary hypertension. Internal Medicine 1994. 33 363–5. ( 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.363) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma RC, Cheng AY, So WY, Hui DS, Tong PC, Chow CC. Thyrotoxicosis and pulmonary hypertension. American Journal of Medicine 2005. 118 927–928. ( 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.038) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marvisi M, Brianti M, Marani G, Borello PD, Bortesi M, Guariglia A. Hyperthyroidism and pulmonary hypertension. Respiratory Medicine 2002. 96 215–220. ( 10.1053/rmed.2001.1260) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armigliato M, Paolini R, Aggio S, Zamboni S, Galasso MP, Zonzin P, Cella G. Hyperthyroidism as a cause of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a prospective study. Angiology 2006. 57 600–606. ( 10.1177/0003319706293131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiura T, Yamanuka S, Takeuchi H, Morimoto N, Kamioka M, Matsumura Y. Autoimmunity and pulmonary hypertension in patients with Graves’ disease. Heart and Vessels 2015. 30 642–646. ( 10.1007/s00380-014-0518-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuhur SS, Baykiz D, Kara SP, Sahin E, Kuzu I, Elbuke G. Relationship between pulmonary hypertension and autoimmunity, thyroid hormones and dyspnoea in patients with hyperthyroidism. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2017. 353 374–380. ( 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.01.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu JW, Kao PN, Faul JL, Doyle RL. High prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2002. 122 1668–1673. ( 10.1378/chest.122.5.1668) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teasdale SL, Inder WJ, Stowasser M, Stanton T. Hyperdynamic right heart function in Graves’ hyperthyroidism measured by echocardiography normalises on restoration of euthyroidism. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2017. 26 580–585. ( 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.10.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song S, Yamamura A, Yamamura H, Ayon RJ, Smith KA, Tang H, Makino A, Yuan JX. Flow shear stress enhances intra-cellular calcium signalling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. American Journal of Physiology: Cell Physiology 2014. 307 373–383. ( 10.1152/ajpcell.00115.2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong JY, Park DG, Yoo JJ, Lee SM, Kim MK, Kim SE, Lee JH, Han KR, Oh DJ. The correlation between left ventricular failure and right ventricular systolic dysfunction occurring in thyrotoxicosis. Korean Circulation Journal 2010. 40 266–271. ( 10.4070/kcj.2010.40.6.266) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a