Abstract

Background

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) actively contributes to the pathological process of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) by enabling NPC cells to acquire various capacities required for their malignant biological actions. Our earlier works demonstrated that EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) enhanced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis by boosting store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) upon extracellular epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation. However, the antagonistic effects of SOCE blockage on EBV-promoted angiogenesis must be appropriately evaluated in vivo, and the global effect of EBV infection on the EGF-elicited cytosolic Ca2+ signaling, which regulates VEGF-mediated angiogenesis remains to be further clarified.

Materials and methods

Two EBV-infected NPC cell lines, CNE2-EBV and HK1-EBV, along with their parental cell lines were employed in the present study. Dynamic cytosolic Ca2+ changes were measured in individual fluorescent Ca2+ indicator-loaded cells. Amounts of VEGF production were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)-formed tube networks were quantitatively evaluated as an in vitro angiogenesis assay. A mouse model concurrently bearing EBV-positive/negative xenografts was utilized to evaluate the tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo.

Results

EBV infection reliably promoted transplanted tumor growth while enhancing angiogenesis. Introduction of EBV into EBV-negative NPC cells increased the EGF-stimulated VEGF production while amplifying the EGF-evoked Ca2+ responses. Inhibition of the EBV-boosted Ca2+ signaling using 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-APB), a specific SOCE inhibitor, effectively antagonized the EBV-promoted VEGF production and endothelial tube formation in vitro. Pharmacological blockage of SOCE exhibited anti-angiogenic effect in the EBV-positive xenografts.

Conclusion

SOCE can serve as a candidate pharmacological target for treating NPC, as blockage of the Ca2+ signaling via SOCE is a feasible strategy to suppress the EBV-driven malignant profiles in NPC cells.

Keywords: nasopharyngeal carcinoma, store-operated Ca2+ entry, angiogenesis, Epstein–Barr virus, vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a distinctive human head-and-neck malignant disease, with an unbalanced geographical and ethnic distribution, high sensitivity to both radiotherapy and chemotherapy, but a strong tendency to spread to regional lymph nodes and distant secondary organs.1,2 The pathogenetic causes for NPC development are diverse and complex, among which latent Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection has been established as being responsible for various malignant biological behaviors of NPC cells.3,4 Latent membrane proteins (LMPs) encoded by EBV, including LMP1 and LMP2A, act as two functional oncogenic proteins that drive the progressive evolution of NPC.5,6

Previously, we reported that inhibition of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) suppressed epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated cell migration and eliminated the extravasation event from the vasculature in NPC cells.7 In our later work, we found that LMP1 promoted cell migration and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by boosting EGF-evoked SOCE, while blocking SOCE effectively blunted the LMP1-enhanced malignant capacities.8 These findings suggest that blockage of the oncogenic signal transduction from an exterior space into the cytoplasm through SOCE-mediated Ca2+ influx can serve as an alternative means to antagonize the EBV-promoted malignant profiles. Our recent study showed that a widely used pharmacological blocker of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ entry, SKF95365, inhibited colony formation and induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at the G2/M and S phases in NPC cells.9 However, within the dose range in which SKF95365 showed obvious inhibitory effects on SOCE, it also increased the apparent Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores and induced significantly increased cell motility,9 indicating that SKF95365 lacks the essential property of selectivity to serve as an SOCE inhibitor for antitumor agents, which may lead to unexpected off-target effects.

In the present study, we aimed to develop a mouse model concurrently bearing EBV-positive/negative xenografts, enabling us to logically evaluate candidate antitumor drugs targeting EBV-driven malignant profiles for NPC treatment in vivo. We further provide an experimental paradigm by validating the effects of blockage of SOCE using a selective pharmacological inhibitor, 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-APB), on tumor-related angiogenesis, which is driven by EBV infection in NPC.3–6

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Guangxi Medical University. Human NPC cell lines CNE2 and HK1 (both are EBV-negative) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin at 100 U/mL, and streptomycin at 100 μg/mL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were routinely maintained in an incubator at 37°C under 5% CO2. CNE2-EBV cells were kindly provided by Prof Musheng Zeng’s group (Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, China), and HK1-EBV cells were kindly gifted by Prof Sai-Wah Tsao (Hong Kong University, China). CNE2-EBV and HK1-EBV cells were established as described previously.10 Briefly, the NPC cells were cocultured with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged neorEBV-infected Akata cells that constantly produce infectious recombinant EBV (rEBV). Then, the NPC cells were incubated in the medium containing G418 for EBV-positive cell selection for 2 weeks.11 Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; CRL-1730™ American Type Culture Collection [ATCC]; Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Ham’s F-12K Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA.) supplemented with 10% FBS, heparin at 0.1 mg/mL, and antibiotics.

Measurement of change in cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt)

The cells were preincubated in serum-free medium for 24 hours before measuring cytosolic Ca2+ to avoid any unexpected stimuli inducing Ca2+ responses. Cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) was measured in individual serum-deprived cells over a time course using a membrane-permeable fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, namely, the acetoxymethyl ester of fura-2 (fura-2-AM) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc, Kumamoto, Japan), as described in our previous studies.7–9,12

Drug and solution

2-APB was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., (St Louis, MO, USA). To avoid any bias resulting from different amounts of DMSO, 2-APB was predissolved in DMSO at various concentrations as stock solutions, which were further added into the medium or PBS (1:1000 dilution) before the experiments, with pH 7.4 at 25°C. Therefore, the amounts of DMSO added into each dosage group were equal. Additionally, an equal amount of DMSO was added into the medium or PBS as a vehicle control, if necessary.

Immunoblotting

EBV-encoded LMP1 expression was detected using western blot analysis (anti-LMP1 antibody, 1:200 dilution; Abcam Corp, Cambridge, UK), according to the standard protocol. α-Tubulin expression was examined as an internal control (anti-alpha-tubulin antibody, 1:500 dilution; Abcam Corp). For the assay, each lane was loaded with 50 μg of protein. The blots were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

VEGF production and in vitro angiogenesis assay

A total of 5×104 NPC cells suspended in medium was seeded into each well of a six-well plate and allowed to grow until an ~85% confluent monolayer was obtained. The cells were preincubated with serum-free medium for 24 hours. Medium containing EGF at 50 ng/mL and 0.25% serum was applied to stimulate VEGF release by the serum-starved NPC cells for 12 hours. The amount of VEGF production in the conditional medium was examined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (VEGF Human ELISA Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The conditioned medium was harvested for a subsequent in vitro tube formation angiogenesis assay utilizing the μ-Plate Angiogenesis 96-well kit (Ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany), as described in previous studies.13 In brief, HUVECs were seeded onto a Matrigel-pretreated surface and allowed to form new vessels with incubation in the cell-conditioned medium. The total tube length in each well was measured to quantitatively evaluate the VEGF-mediated angiogenesis using WimTube Image Analysis (Ibidi GmbH).

Nude mouse xenograft

All of the in vivo experiments performed in our study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.14 All experiments were performed in accordance with the regulations of the Animal Research Committee of Guangxi Medical University. All the experiments were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Guangxi Medical University. The bilateral dorsal sites of female BALB/c(nu/nu) mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were subcutaneously inoculated with 5×106 EBV-negative (mock control, right side) and EBV-infected CNE2 cells (left side). Five or seven mice were assigned to each experimental group, as indicated. Palpable xenografts could be observed 10 days after the inoculations. The tumor dimensions were measured every 5 days using a vernier caliper, and the xenograft volumes were calculated according to the formula V = (W2 × L)/2, where W was the width and L was the length. At the end of the xenograft growth observation, the mice were anesthetized and perfused with PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde; then, the mice were sacrificed and the transplanted tumors were isolated. The tumor tissues were subjected to routine paraffin-embedded sectioning followed by immunohistochemical analysis of angiogenesis. A well-known vascular endothelial marker, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, PECAM-1/CD31, was detected to estimate angiogenesis within the xenografts.

Results

EBV infection accelerates xenograft growth by promoting tumor-related angiogenesis

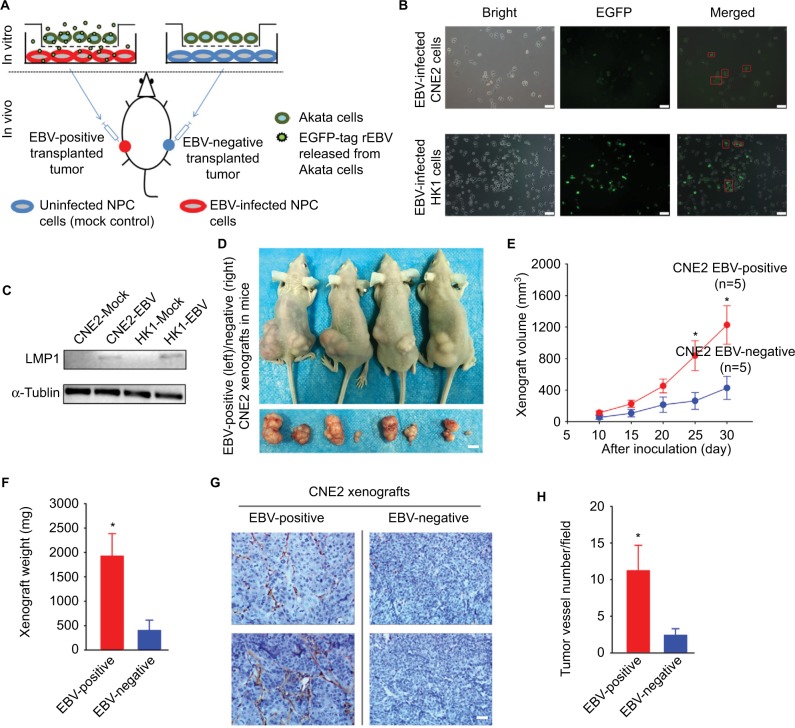

The protocol of establishing of a mouse model bearing both EBV-positive and EBV-negative xenografts is briefly illustrated (Figure 1A). A sequence encoding EGFP was simultaneously introduced into the CNE2 and HK1 cells accompanied with the in vitro EBV infection, as described previously.10,11 The EGFP thus served as a visible tag enabling dynamic and real-time monitoring of the EBV infection (Figure 1B). To further validate the effectiveness of the EBV infection, immunoblotting was performed to detect the expression of a well-characterized oncoprotein that is encoded by EBV, namely, LMP1, in CNE2-EBV and HK1-EBV cells after 2 weeks of cell selection with Geneticin antibiotic treatment (Figure 1C). The tumor-associated neovasculature is crucial for tumor growth, as it supplies the proliferative cancer cells with abundant oxygen and nutrients and allows for the evacuation of metabolic waste. To evaluate the effects of EBV infection on tumor-associated angiogenesis and NPC tumor growth, EBV-positive and EBV-negative CNE2 cells were inoculated at bilateral dorsal sites, whereby EBV-positive cells were implanted on the left and EBV-negative cells on the right (Figure 1D). The EBV-positive xenografts grew faster compared with the EBV-negative xenografts (Figure 1E and F). In addition, by performing immunohistochemical analysis, we demonstrated that the neovasculature within the transplanted tumors was significantly enhanced in the EBV-positive xenografts (Figure 1G and H), reflecting the well-known fact that EBV infection promotes tumor-associated angiogenesis.3–6 The mouse model established here reliably showed enhanced tumor-associated angiogenesis and tumor growth promoted by EBV, thus enabling the subsequent in vivo antitumor drug screening and efficacy validation in NPC.

Figure 1.

EBV infection promotes xenograft growth and tumor-associated angiogenesis in vivo.

Notes: (A) The scheme for establishing an EBV-positive/EBV-negative xenograft-bearing mouse model is illustrated. (B) The EGFP-encoding sequence was simultaneously introduced into CNE2 and HK1 cells with the infectious rEBV, which served as a visible indicator for the EBV-positive cells. The red square boxes denote the EGFP-labeled EBV-positive cells that were captured after the co-cultivated EBV infection. Scale bar =50 μm; 200× magnification. (C) After antibiotic resistance-based cell selection, clonal populations of cells were selected by transferring a well-isolated single clump of cells. EBV-encoded LMP1 was detected by western blotting in mock-controlled and EBV-infected CNE2 and HK1 cells. The selected EBV-positive CNE2 and HK1 cells were used for subsequent experiments. (D) Representative photographs of the female BALB/c(nu/nu) mice harboring both EBV-positive (left) and EBV-negative (right) xenografts were captured on Day 30 postinoculation. The dissected xenografts are shown in each bottom panel. Scale bar =10 mm. (E) The xenograft volumes were measured every 5 days from Day 10 postinoculation, when palpable xenografts could be observed (n=5). (F) The EBV-positive and EBV-negative xenografts were isolated from the sacrificed mice on Day 30 and weighed. (G) The representative immunohistochemical analysis of CD31 in the paraffin-embedded xenograft sections. (H) Tumor-associated angiogenesis was quantitatively evaluated by determining the vessel numbers per field. Scale bar =100 μm; 400× magnification. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (*P<0.05, paired t-test).

Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; LMP1, latent membrane protein 1; rEBV, recombinant EBV.

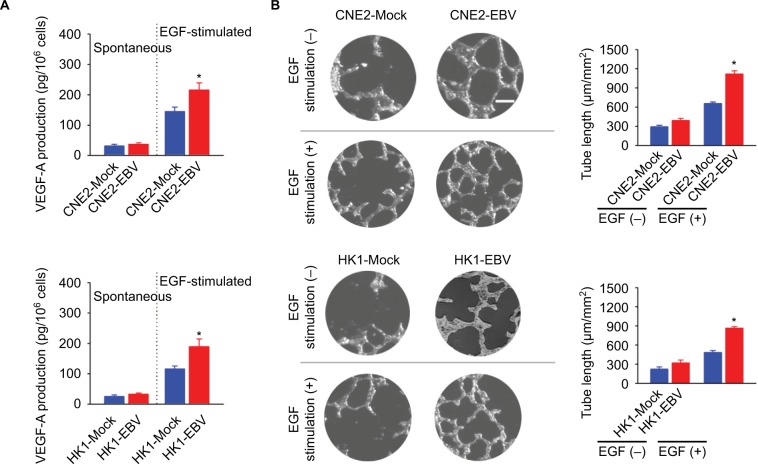

EBV infection increases EGF-stimulated VEGF production and enhances endothelial tube formation

Cancer cell-released VEGF is a key exocrine molecule that mobilizes the surrounding endothelial cells to form the endothelium for vascularization. Therefore, we further determined VEGF production in the EBV-infected CNE2 and HK1 cells. The amounts of spontaneous VEGF production were not significantly different between the EBV-positive and EBV-negative cells. However, VEGF production in the EBV-infected cells in the presence of external EGF stimulation was significantly increased (Figure 2A). To further elucidate the effect of EBV infection on VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, an endothelial tube formation assay was used. The in vitro angiogenesis assay showed that EBV infection promoted endothelial tube formation significantly in the presence of EGF stimulation (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

EBV infection promotes EGF-stimulated VEGF production and endothelial tube formation.

Notes: (A) VEGF-A production was determined in the mock-controlled and the EBV-infected CNE2 or HK1 cell-conditioned medium. The amount of VEGF released from the serum-starved cells in the absence or presence of extracellular EGF stimulation was determined by ELISA. (B) HUVECs were incubated with the cell-conditioned medium as indicated. Representative photographs of HUVEC tube formation were captured at 6 hours after cell seeding; scale bar =100 μm. The tube formation was quantitatively evaluated by calculating the tube length per standard area in each well (right panel). The data are representative of three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SEM (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test).

Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

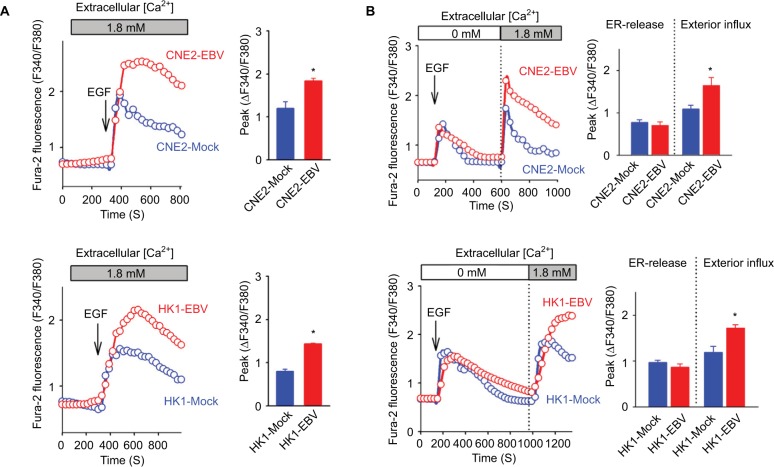

EBV infection promotes EGF-evoked Ca2+ influx via SOCE

It is well established that the VEGF produced and released by cancer cells can be manipulated by Ca2+ signaling.15,16 In our previous study, we showed that EBV-encoded LMP1 augmented VEGF production by boosting the Ca2+ responses via SOCE.8 However, the global effects of EBV infection on cytosolic Ca2+ signaling, which implicated VEGF production, still remain unclear. In the present study, we tested the Ca2+ responses in two EBV-infected NPC cell lines, CNE2-EBV and HK1-EBV cells, compared to their mock controls. EBV infection significantly boosted the immediate cytosolic Ca2+ elevation found upon external EGF stimulation (Figure 3A). According to a standard protocol for characterizing SOCE, we confirmed that EBV promoted the Ca2+ responses by boosting the Ca2+ influx via the plasma membrane Ca2+ channels but had no obvious effect on the Ca2+ release from the intracellular Ca2+ store, namely, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 3B). Thus, EBV infection promotes tumor-associated angiogenesis by amplifying the Ca2+ signaling via SOCE, which regulates VEGF production.

Figure 3.

EBV infection amplifies EGF-stimulated Ca2+ signaling via SOCE.

Notes: (A) EGF-evoked Ca2+ transient responses were measured in the fura-2-loaded cells. The dynamic cytosolic Ca2+ level [Ca2+]cyt was measured as the fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) of fura-2. Each trace represents the average data from at least 20 individual cells. The intensities of Ca2+ responses were quantitatively evaluated by calculating the average peak from the baseline in each right panel. (B) EGF-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores (ER) and the following Ca2+ influx via membrane channels were measured in the absence and presence of extracellular Ca2+, successively. The data are representative of three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SEM (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test).

Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

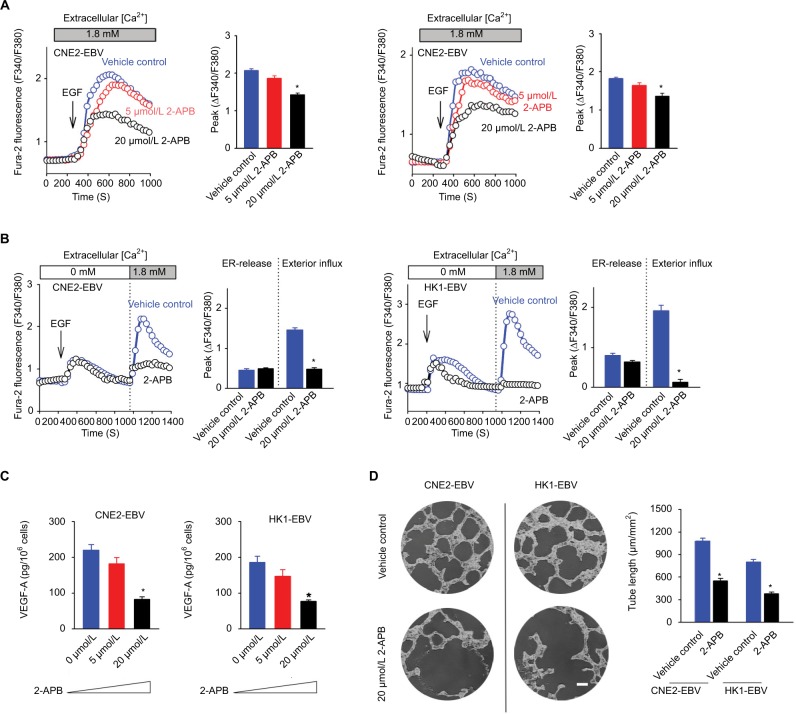

2-APB blunts the EBV-promoted VEGF production and endothelial tube formation while inhibiting EGF-activated SOCE

2-APB was initially recognized as a membrane-permeable modulator of intracellular inositol triphosphate (IP3)-induced Ca2+ release.17 However, later studies have demonstrated that the main pharmacological antagonistic effect of 2-APB is on SOCE, rather than on IP3-induced Ca2+ release.18 In this study, 2-APB at 5 μmol/L slightly inhibited the EGF-stimulated transient Ca2+ increases, while at 20 μmol/L, 2-APB exhibited obvious inhibitory effects (Figure 4A). Because 2-APB can not only inhibit SOCE but may also affect the ER-released Ca2+ and because this pharmacological property varies in different cell types,17,19 we determined the effects of 2-APB on ER-released Ca2+ and the following activated SOCE. 2-APB showed no obvious effect on intracellular Ca2+ release but obviously inhibited the Ca2+ influx via SOCE in CNE2-EBV cells (Figure 4B). Similarly, 2-APB did not significantly affect the peak of the ER-released Ca2+ and only slightly influenced the duration of Ca2+ elevation in HK1-EBV cells while almost blocking the subsequent Ca2+ influx via SOCE (Figure 4B). As expected, 2-APB at 5 μmol/L mildly affected the EGF-stimulated VEGF production in both the EBV-infected CNE2 and HK1 cells, and 2-APB at 20 μmol/L obviously reduced the amount of VEGF (Figure 4C). Moreover, 2-APB at 20 μmol/L suppressed the VEGF-driven endothelial tube formation (Figure 4D), which was shown to be promoted by EBV infection in the present study (Figure 2B).

Figure 4.

2-APB blunts EBV-promoted endothelial tube formation mediated by VEGF.

Notes: (A) Effects of 2-APB at increasing concentrations on EGF-evoked Ca2+ responses are shown. (B) Effects of 2-APB at 20 μmol/L on EGF-induced Ca2+ release from the ER and the following SOCE were measured in the absence and presence of extracellular Ca2+, successively. (C) Effects of 2-APB at various concentrations on VEGF-A production upon EGF stimulation were determined by ELISA. (D) Effects of 2-APB on endothelial tube formation are shown; scale bar =100 μm. The data are representative of three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SEM (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test).

Abbreviations: 2-APB, 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; SOCE, store-operated Ca2+ entry.

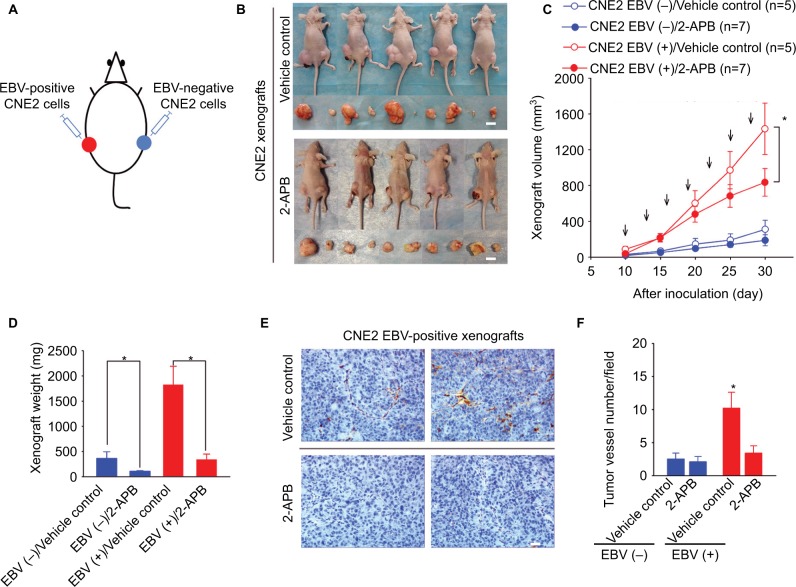

2-APB antagonizes EBV-positive xenograft growth by inhibiting EBV-promoted angiogenesis

We further examined the effects of 2-APB on transplanted NPC tumor growth in the xenograft-bearing mouse model described earlier (Figure 5A). Intraperitoneal injection of 2-APB into the mice harboring NPC xenografts resulted in a reduction in the EBV-positive tumor growth, determined by the measured volumes and weights of the xenografts (Figure 5B–D). Furthermore, 2-APB also effectively inhibited EBV-promoted angiogenesis, as determined by the intratumor vessel number detected through the immunohistochemical analysis of the xenograft sections (Figure 5E). 2-APB also mildly decreased the EBV-negative xenograft growth (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

2-APB effectively blunts EBV-promoted xenograft growth and angiogenesis.

Notes: (A) The scheme for the xenograft model in mice. (B) Female BALB/c(nu/nu) mice harboring both EBV-positive and EBV-negative xenografts were treated with (a) PBS (vehicle control) or (b) 2-APB. Representative photographs of the xenograft-bearing mice were captured on Day 30 postinoculation. The xenografts isolated from each mouse are shown in the bottom panel. Scale bar =10 mm. (C) The xenograft volumes were measured every 5 days from Day 10 postinoculation. The mice were intraperitoneally injected every 3 days (arrows) with 2-APB (50 μg/kg; n=7) or control vehicle (PBS; n=5) from the 10th day postinoculation. (D) The weights of the xenografts were determined. (E) The representative immunohistochemical analysis of CD31 in the paraffin-embedded EBV-positive xenograft sections. Scale bar =100 μm; 400× magnification. (F) The tumor-associated angiogenesis was quantified as the vessel numbers per field (400× magnification). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test or paired t-test).

Abbreviations: 2-APB, 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate; Ctrl, control; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus.

Discussion

EBV latent infection has been established as a key pathogenetic factor for the progression of EBV-associated malignant diseases, such as Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, some natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphomas, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease, and NPC.3 EBV-encoded oncofunctional molecules, such as the LMPs LMP1 and LMP2A, enable NPC cells to acquire various malignant phenotypes required for tumorigenesis.4,5 EBV-encoded LMP1 plays an integral part during NPC pathogenesis.6 LMP1 exerts oncogenic properties by inducing various phenotypic alterations in NPC cells, including resistance to apoptosis, modulation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), as well as promotion of migration, invasion, and angiogenesis.6 In our previous study, we demonstrated that LMP1 enhanced VEGF production by amplifying the external EGF-evoked Ca2+ signaling via SOCE.8 Thus, blockage of EBV-manipulated Ca2+ signaling might serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for treating NPC. In our recent work, we reported that SKF96365, an inhibitor of the store-operated Ca2+ channel, inhibited colony formation and induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in NPC cells.9 However, SKF96365 also affected cytosolic Ca2+ signaling by directly inducing ER-released Ca2+, which was presumably responsible for the increased cell mortality.9 These results indicated that SKF96365 is not suitable for evaluating the effects of pharmacological blockage of SOCE on EBV-driven malignant profiles, such as migration, invasion, and angiogenesis, due to its toxic off-target effects. In the present study, we further tested the possibility that pharmacological blockage of SOCE using 2-APB, which was confirmed to have no obvious inhibitory effect on NPC cell proliferation in our previous study,7 could affect EBV-promoted angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo.

In this study, we showed that infection by EBV in two EBV-negative NPC cell lines, CNE2 and HK1, amplified the extracellular EGF-evoked Ca2+ influx via SOCE (Figure 3B). It is well-characterized that EBV-encoded LMPs profoundly remodel EGFR activation-launched signaling by functionalizing EGFR.20–23 Our earlier findings indicated that EBV-encoded LMP1 aggrandized EGF-stimulated Ca2+ signaling by enhancing Orai1 expression, a key component of membrane Ca2+ channels for SOCE.8 However, the solo ectopic expression of LMP1 might not completely reflect the entire picture of EBV infection on NPC cells, as proposed in our previous study.8 To achieve a full view of how EBV affects SOCE-mediated Ca2+ signaling, two EBV-infected NPC cell lines were used, which were generated by in vitro cell-to-cell cross-infection.10,11 Compared with the mock controls, the EBV-infected NPC cells showed amplified Ca2+ responses upon external EGF stimulation (Figure 3A), which was consistent with the results from LMP1-expressing cells in our earlier work.8

VEGF is a crucial mediator for tumor-associated angiogenesis. Cancer cells utilize VEGF to mobilize the surrounding endothelial cells expressing VEGFR to construct a continuous endothelium, which is strictly required for the newly generated vasculature.16 Interfering in this pathological cell–cell communication between cancer cells and the nearby noncancer cells, such as targeting VEGFR, has become a promoting strategy for treating human malignancies, including NPC.24,25 In general, the growing cancer cells actively release VEGF within the hypoxic microenvironment or upon stimulation of external proliferative signals such as EGF. Herein, we showed that EBV infection promoted EGF-stimulated VEGF production in NPC cells while boosting EGF-evoked Ca2+ responses via SOCE (Figures 2A and 3A and B). Thus, we hypothesized that the amplified Ca2+ signaling that regulates cell exocytosis was responsible for the enhanced VEGF release from the EBV-infected NPC cells.26 Indeed, 2-APB, a pharmacological inhibitor of SOCE, effectively decreased the Ca2+ influx via SOCE without obviously affecting ER-released Ca2+ (Figure 4A and B) while reducing EGF-stimulated VEGF production in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4C). Our results therefore strongly suggested that EBV infection promotes tumor angiogenesis by amplifying cytosolic Ca2+ signaling via SOCE, which is responsible for the regulation of VEGF secretion. Hence, effective reduction of the Ca2+ signaling could serve as a means to antagonize the EBV-promoted angiogenesis. To test this possibility, we further performed endothelial tube formation assays to elucidate the effect of 2-APB on angiogenesis in vitro. We found that 2-APB significantly inhibited EBV-promoted endothelial tube formation (Figures 2B and 4D).

Abnormal neovasculature formation is considered a hallmark of human cancers.27 The aberrantly generated vessels not only supply the proliferative cancer cells with nutrients and oxygen but also allow for the removal of metabolites. In the present study, we compared the growth of the EBV-positive transplanted tumors with the mock-controlled EBV-negative tumors in mice. The EBV-positive xenografts grew significantly faster than the EBV-negative controls, while more intensive vessel formation was also observed (Figure 1E–H). EBV-enhanced tumor growth and angiogenesis could be clearly observed in the same individual animal (Figure 1D and G). Of note, the promotions of tumor growth and angiogenesis shown in this model were solely attributed to EBV infection, as the bias usually caused by the physiological differences between individual animals was completely eliminated. Using this in vivo model, we showed that 2-APB effectively inhibited the growth of the EBV-positive xenografts by decreasing tumor-associated angiogenesis in vivo (Figure 5C–F).

In our earlier work on various membrane Ca2+ channels, we identified Ca2+ influx via SOCE as the predominant Ca2+ signaling that regulates extracellular EGF-stimulated cell migration in NPC cells.7 In our later study, we demonstrated that EBV-encoded LMP1 promoted EGF-induced cell migration while amplifying the EGF-evoked Ca2+ responses, whereas blocking SOCE by either pharmacological inhibitor or knockdown of ORAI1, which forms the functional unit of the membrane entries allowing Ca2+ influx for SOCE, blunted the LMP1-promoted malignant profiles, such as migration/invasion, angiogenesis, permeabilization of the endothelium, extravasation from the vasculature, and distant colonization.8 Taking our earlier findings together, pharmacological blockage of the EBV-boosted Ca2+ signaling via SOCE could serve as a feasible approach to antagonize the EBV-driven malignant biological behaviors. The mouse model concurrently bearing EBV-positive and EBV-negative xenografts is a powerful way to clarify the underlying mechanism through which EBV infection actively contributes to NPC development and is ideal for the in vivo screening of potential pharmacological targets and the verification of candidate antitumor drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (numbers 81560438 and 81602390), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (numbers 2016GXNS-FCB380003 and 2015GXNSFCA139014), a grant from the Key Laboratory of Ministry of Education, Early Stage Prevention and Control of Regional High-Incidence Cancer in Guangxi (number GJK201601), and a grant from Guangxi Medical University Training Program for Distinguished Young Scholars.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Vokes EE, Liebowitz DN, Weichselbaum RR. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 1997;350(9084):1087–1091. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao Q, Chan AT. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic developments. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2007;9(12):1–24. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of NPC. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12(6):431–441. doi: 10.1016/s1044579x0200086x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson CW, Port RJ, Young LS. The role of the EBV-encoded latent membrane proteins LMP1 and LMP2 in the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22(2):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshizaki T, Kondo S, Wakisaka N, et al. Pathogenic role of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 in the development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2013;337(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Wei J, Kanada M, et al. Inhibition of store-operated Ca2+ entry suppresses EGF-induced migration and eliminates extravasation from vasculature in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell. Cancer Lett. 2013;336(2):390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei J, Zhang J, Si Y, et al. Blockage of LMP1-modulated store-operated Ca(2+) entry reduces metastatic potential in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell. Cancer Lett. 2015;360(2):234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Wei J, He Q, et al. SKF95365 induces apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest by disturbing oncogenic Ca(2+) signaling in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3123–3133. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S92005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo AK, Lo KW, Tsao SW, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection alters cellular signal cascades in human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8(3):173–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.05625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruo S, Yang L, Takada K. Roles of Epstein-Barr virus glycoproteins gp350 and gp25 in the infection of human epithelial cells. J Gen Virol. 2001;82(pt 10):2373–2383. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-10-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei J, Takeuchi K, Watanabe H. Linoleic acid attenuates endothelium-derived relaxing factor production by suppressing cAMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase activity. Circ J. 2013;77(11):2823–2830. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law EW, Cheung AK, Kashuba VI, et al. Anti-angiogenic and tumor-suppressive roles of candidate tumor-suppressor gene, Fibulin-2, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2012;31(6):728–738. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YF, Chiu WT, Chen YT, et al. Calcium store sensor stromal-interaction molecule 1-dependent signaling plays an important role in cervical cancer growth, migration, and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(37):15225–15230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103315108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muralidharan-Chari V, Clancy JW, Sedgwick A, D’Souza-Schorey C. Microvesicles: mediators of extracellular communication during cancer progression. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(pt 10):1603–1611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca2+ release. J Biochem. 1997;122(3):498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Berridge MJ, Peppiatt CM. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 2002;16(10):1145–1150. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0037rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soulsby MD, Wojcikiewicz RJ. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate inhibits inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor function, ubiquitination and downregulation, but acts with variable characteristics in different cell types. Cell Calcium. 2002;32(4):175–181. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WE, Earp HS, Raab-Traub N. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Virol. 1995;69(7):4390–4398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4390-4398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornburg NJ, Raab-Traub N. Induction of epidermal growth factor receptor expression by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 C-terminal-activating region 1 is mediated by NF-kappaB p50 homodimer/Bcl-3 complexes. J Virol. 2007;81(23):12954–12961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01601-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung CP, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor through effects on Bcl-3 and STAT3. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5486–5493. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00125-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kung CP, Meckes DG, Jr, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 activates EGFR, STAT3, and ERK through effects on PKCdelta. J Virol. 2011;85(9):4399–4408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01703-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elser C, Siu LL, Winquist E, et al. Phase II trial of sorafenib in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3766–3773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee NY, Zhang Q, Pfister DG, et al. Phase II study of the addition of bevacizumab to standard chemoradiation for loco-regionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trial 0615. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(2):172–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70303-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131(6):1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]