Abstract

The absence of major progress in the treatment of glioblastoma (GBM) is partly attributable to our poor understanding of both GBM tumor biology and the acquirement of treatment resistance in recurrent GBMs. Recurrent GBMs are characterized by their resistance to radiation. In this study, we used an established stable U87 radioresistant GBM model and total RNA sequencing to shed light on global mRNA expression changes following irradiation. We identified many genes, the expressions of which were altered in our radioresistant GBM model, that have never before been reported to be associated with the development of radioresistant GBM and should be concertedly further investigated to understand their roles in radioresistance. These genes were enriched in various biological processes such as inflammatory response, cell migration, positive regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, apoptosis, positive regulation of T-cell migration, positive regulation of macrophage chemotaxis, T-cell antigen processing and presentation, and microglial cell activation involved in immune response genes. These findings furnish crucial information for elucidating the molecular mechanisms associated with radioresistance in GBM. Therapeutically, with the global alterations of multiple biological pathways observed in irradiated GBM cells, an effective GBM therapy may require a cocktail carrying multiple agents targeting multiple implicated pathways in order to have a chance at making a substantial impact on improving the overall GBM survival.

Keywords: glioblastoma, acid ceramidase, acid ceramidase inhibitors, carmofur, radioresistance

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM), with an overall survival of less than 1.5 years and a 5-year survival rate of 5%, is the most common, malignant primary cancer of the central nervous system in adults, with an estimated 12,120 new diagnoses in the United States alone in 2016 [1–3]. The current standard treatment regimen for GBM consists of maximal safe surgical resection, followed by the Stupp regimen, which consists of radiation therapy combined with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide [4, 5]. Despite this, recurrence—characterized by radioresistance—is inevitable [6, 7]. To elucidate the underlying mechanism of radioresistance, we recently established a stable, radioresistant GBM model and also presented evidence partly attributing the radioresistance of GBM cells to radiation-induced upregulation of tumor promoters acid ceramidase (ASAH1) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) [8, 9]. ASAH1 is a lysosomal cysteine amidase that converts ceramides, which trigger senescence and apoptosis, into sphingosine and free fatty acids [10–17]. Subsequently, sphingosine is phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase 1 (SPHK1) or 2 (SPHK2) to form a tumor promoter, S1P [10–15]. However, the radiation effects on global gene expression at the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) level in a stable radioresistant GBM model have never been investigated.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a powerful technique for transcriptome profiling of cell lines of interest to explain phenotypic variations [18, 19]. This study used RNA-seq to reveal many crucial radiation-responsive genes that may enable GBM cells to acquire resistance to radiation, providing the essential basis for further investigations of the role of these differential mRNA expressions in acquiring radioresistance.

RESULTS

Irradiation of GBM cells induced differential expression of 1094 radiation-responsive genes

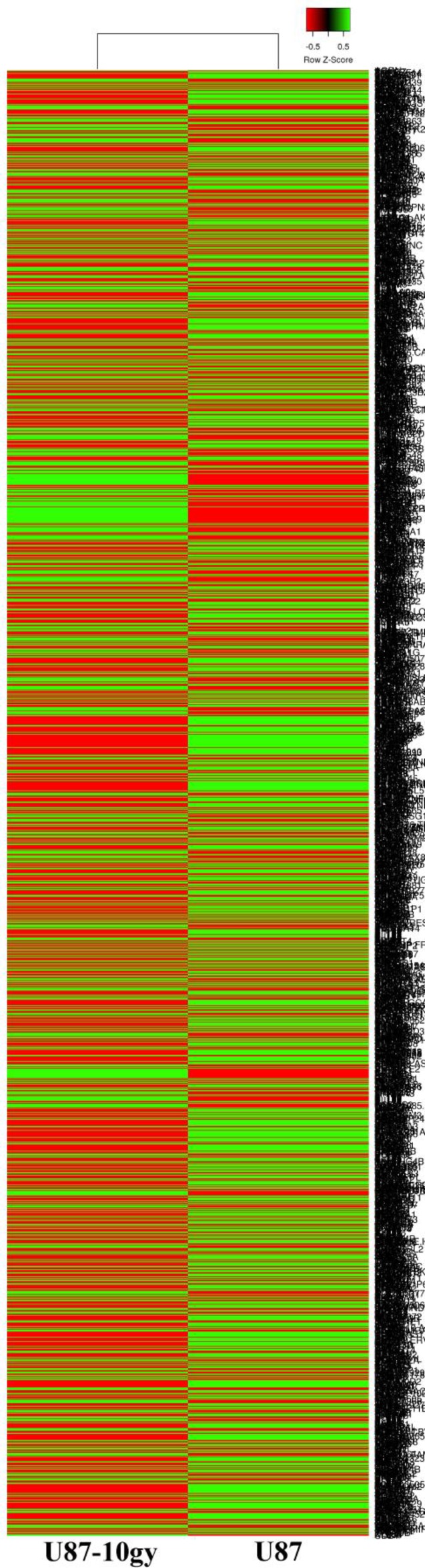

We previously generated and described a stable radioresitant GBM model. Briefly, U87 cells received a total radiation of 10 Gy to generate radioresistant U87-10gy cells. Over the course of weeks, most cells died and less than ~1% of cells survived the irradiation. These radioresitant U87-10 gy cells were allowed to grow to confluence and were perpetuated for experiments. Total RNAs from U87 and U87-10 gy cells were harvested and subjected to further analysis. To screen for global mRNA changes following irradiation, we profiled transcriptomes of the control U87 cell line and its derivatives irradiated U87-10gy cells via RNA sequencing (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Using genes with twofold changes or greater with statistically significant values (P < 0.05) as criteria, we identified 1094 radiation responsive genes that were upregulated or downregulated in U87-10gy vs U87 cells. Among these 1094 radiation responsive genes, 427 were upregulated and 667 were downregulated (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1. Clustered heat map of RNA-seq transcriptomes of U87 and U87-10gy cells.

U87 and U87-10gy cells were subjected to RNA sequencing. Experiments were performed in triplicates, and only genes with statically significant changes (~2000 genes) were utilized for the heat map. Green: relatively high expression, Red: relatively low expression. (P < 0.05)

Upregulation of genes promoting tumor aggressiveness and invasion following irradiation

In an effort to categorize genes based on their functions, we performed a gene ontology analysis. This analysis revealed that upregulated genes were enriched in inflammatory response, cell migration, positive regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, cell proliferation, cell growth, positive regulation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, response to hypoxia, activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase activity, metalloendopeptidase activity, cellular response to fibroblast growth factor stimulus, cellular response to transforming growth factor beta stimulus, cellular response to tumor necrosis factor, and ribonuclease A activity genes (Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Tables 2 and 4).

Table 1. Enriched gene ontology categories of differentially expressed genes following irradiation based on sets of statistically significant upregulated and downregulated genes (P < 0.05).

| Differentially Expressed | Category | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| GO:0007165: Signal transduction | 6.90E–04 | |

| GO:0006351: Transcription, DNA-templated | 7.40E–03 | |

| GO:0008152: Metabolic process | 1.50E–04 | |

| GO:0006915: Apoptotic process | 6.60E–04 | |

| Downregulated | GO:0007155: Cell adhesion | 1.50E–03 |

| GO:0072332: Intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway by p53 class mediator | 1.10E–02 | |

| GO:0045746: Negative regulation of Notch signaling pathway | 7.00E–02 | |

| GO:2000406: Positive regulation of T-cell migration | 4.10E–02 | |

| GO:0010759: Positive regulation of macrophage chemotaxis | 5.00E–02 | |

| GO:0002457: T-cell antigen processing and presentation | 9.60E–02 | |

| GO:0002282: Microglial cell activation involved in immune response | 9.60E–02 | |

| GO:0006954: Inflammatory response | 1.60E–04 | |

| GO:0016477: Cell migration | 2.90E–04 | |

| GO:0010718: Positive regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition | 4.90E–03 | |

| GO:0001525: Angiogenesis | 2.00E–02 | |

| GO:0008283: Cell proliferation | 2.30E–02 | |

| GO:0016049: Cell growth | 3.00E–02 | |

| Upregulated | GO:0090263: Positive regulation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway | 4.10E–02 |

| GO:0001666: Response to hypoxia | 2.90E–02 | |

| GO:0000187: Activation of MAPK activity | 7.50E–02 | |

| GO:0004222: Metalloendopeptidase activity | 5.70E–04 | |

| GO:0004522: Ribonuclease A activity | 8.00E–02 | |

| GO:0071356: Cellular response to tumor necrosis factor | 2.30E–04 | |

| GO:0044344: Cellular response to fibroblast growth factor stimulus | 2.50E–02 | |

| GO:0071560: Cellular response to transforming growth factor beta stimulus | 1.90E–02 |

Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Table 2. Upregulated genes of selected enriched gene ontology categories following irradiation are shown based on sets of statistically significant changes (P < 0.05).

| Gene Ontology Category | P-value | Fold change | Gene symbol | Gene description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0010718:Positive regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition | 4.90E–03 | 2.32 | BAMBI | BMP and activin membrane bound inhibitor |

| 2 | GLIPR2 | GLI pathogenesis related 2 | ||

| 2.23 | AXIN2 | axin 2 | ||

| 4.78 | COL1A1 | collagen type I alpha 1 chain | ||

| 2.79 | TGFB3 | transforming growth factor beta 3 | ||

| GO:0001525: Angiogenesis | 2.00E–02 | 2.46 | CXCL8 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 |

| 5.1 | EPHB3 | EPH receptor B3 | ||

| 2.2 | EPHB4 | EPH receptor B4 | ||

| 5.79 | ACKR3 | atypical chemokine receptor 3 | ||

| 2 | CSPG4 | chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 | ||

| 2.48 | COL8A1 | collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain | ||

| 3 | NRXN3 | neurexin 3 | ||

| 3.16 | NDNF | neuron derived neurotrophic factor | ||

| 3.68 | NRP2 | neuropilin 2 | ||

| 2.611 | SERPINE1 | serpin family E member 1 | ||

| 3.2 | ZC3H12A | zinc finger CCCH-type containing 12A | ||

| GO:0016049: Cell growth | 3.00E–02 | 14.44 | ROS1 | ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase |

| 3.07 | EDN1 | endothelin 1 | ||

| 2.43 | IL7R | interleukin 7 receptor | ||

| 3.16 | NDNF | neuron derived neurotrophic factor | ||

| 2.79 | TGFB3 | transforming growth factor beta 3 | ||

| GO:0008283: Cell proliferation | 2.30E–02 | 2.18 | E2F8 | E2F transcription factor 8 |

| 4.84 | ERG | ERG, ETS transcription factor | ||

| 14.44 | ROS1 | ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase | ||

| 4.47 | ALK | anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase | ||

| 2.23 | AXIN2 | axin 2 | ||

| 3 | CDC25A | cell division cycle 25A | ||

| 2.02 | CSPG4 | chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 | ||

| 4.19 | CYP1A1 | cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1 | ||

| 3.23 | DLX5 | distal-less homeobox 5 | ||

| 2.14 | FSCN1 | fascin actin-bundling protein 1 | ||

| 2.76 | FGF5 | fibroblast growth factor 5 | ||

| 2.62 | GRPR | gastrin releasing peptide receptor | ||

| 5.56 | MYH10 | myosin heavy chain 10 | ||

| 2.47 | PDK1 | pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 | ||

| 2.25 | UHRF1 | ubiquitin like with PHD and ring finger domains 1 | ||

| GO:0004222: Metalloendopeptidase activity | 5.70E–04 | 3 | ADAM12 | ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 |

| 2.79 | ADAM19 | ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 | ||

| 2.59 | ADAMTS1 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 1 | ||

| 2.73 | ADAMTS14 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 14 | ||

| 2.25 | BMP1 | bone morphogenetic protein 1 | ||

| 3.15 | MMP12 | matrix metallopeptidase 12 | ||

| 5.55 | MMP3 | matrix metallopeptidase 3 | ||

| 5.69 | MMP7 | matrix metallopeptidase 7 | ||

| 2.35 | MME | membrane metalloendopeptidase | ||

| 2.4 | TSHZ2 | teashirt zinc finger homeobox 2 | ||

| GO:0001666: Response to hypoxia | 2.90E–02 | 5.69 | ABAT | 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase |

| 2.73 | BNIP3 | BCL2 interacting protein 3 | ||

| 5.6 | CA9 | carbonic anhydrase 9 | ||

| 4.17 | CYP1A1 | cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1 | ||

| 3.84 | EGLN3 | egl-9 family hypoxia inducible factor 3 | ||

| 2.25 | LOXL2 | lysyl oxidase like 2 | ||

| 2.72 | MUC1 | mucin 1, cell surface associated | ||

| 10.81 | POSTN | periostin | ||

| 2.79 | TGFB3 | transforming growth factor beta 3 | ||

| 1.80 | HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha | ||

| GO:0016477: Cell migration | 2.90E–04 | 2.32 | BAMBI | BMP and activin membrane bound inhibitor |

| 2.39 | EPHA3 | EPH receptor A3 | ||

| 5.1 | EPHB3 | EPH receptor B3 | ||

| 4.84 | ERG | ERG, ETS transcription factor | ||

| 2.95 | WWC1 | WW and C2 domain containing 1 | ||

| 2.06 | BDKRB1 | bradykinin receptor B1 | ||

| 2 | CSPG4 | chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 | ||

| 2.41 | COL5A1 | collagen type V alpha 1 chain | ||

| 2.14 | FSCN1 | fascin actin-bundling protein 1 | ||

| 3.66 | LCP1 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 | ||

| 3.3 | PODXL | podocalyxin like | ||

| 4.48 | PSG2 | pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 2 | ||

| 2.83 | SDC1 | syndecan 1 |

Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Many genes involved in enhancement of tumor aggressiveness and invasion were significantly induced by irradiation (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). For example, the upregulation of BNIP3, MMP3, MMP7, MMP15, TGFBI, NOTCH2, AKT1, AKT3, TNFAIP3, RRM2, CXCL8, FOXM1, HMOX1, PRMT5, KDM2B, CERS6, SPHK1, ZBTB18, and PDK1 have been linked to radioresistance and increased aggressiveness of irradiated GBM cells [20–40]. In their study of irradiated GBM cells, Maachani et al. revealed FOXM1 confers radioresistance in GBM cells [31]. AKT1 and PDK1 induce resistant to chemotherapy such as temozolomide [39, 40]. In addition, AKT1 plays a major role in DNA repair of double-stranded breaks [40].

Tumor suppressor, immune response, P-53-dependent apoptosis, and cell adhesion genes are enriched in the pool of downregulated genes

The gene ontology analysis was conducted to analyze differentially expressed genes. Compared with control U87 cells, downregulated genes in irradiated U87-10gy cells were enriched in signal transduction, transcription DNA-templated, metabolic pathway, apoptotic process, cell adhesion, intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway by p53 class mediator, positive regulation of T-cell migration, positive regulation of macrophage chemotaxis, T-cell antigen processing and presentation, and microglial cell activation involved in immune response genes (Tables 1 and 3, and Supplementary Tables 3 and 5).

Table 3. Downregulated genes of selected enriched gene ontology categories following irradiation are shown based on sets of statistically significant changes (P < 0.05).

| Gene Ontology Category | P-value | Fold change | Gene symbol | Gene description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0006915: Apoptotic process | 6.60E–04 | 4.30E–01 | BBC3 | BCL2 binding component 3 |

| 7.90E–02 | DCC | DCC netrin 1 receptor | ||

| 1.90E–01 | PYCARD | PYD and CARD domain containing | ||

| 4.10E–01 | TRAF5 | TNF receptor associated factor 5 | ||

| 1.30E–01 | XAF1 | XIAP associated factor 1 | ||

| 4.10E–01 | BEX2 | brain expressed X-linked 2 | ||

| 2.80E–01 | CASP1 | caspase 1 | ||

| 1.60E–01 | CTSH | cathepsin H | ||

| 2.30E–01 | C5AR1 | complement C5a receptor 1 | ||

| 1.50E–01 | ELMO1 | engulfment and cell motility 1 | ||

| 4.50E–01 | IL1B | interleukin 1 beta | ||

| 2.60E–01 | MAP2K6 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 | ||

| 4.70E–01 | NR4A1 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 | ||

| 3.70E–01 | PMAIP1 | phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 | ||

| 1.10E–03 | SFRP2 | secreted frizzled related protein 2 | ||

| 4.80E–01 | YARS | tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | ||

| GO:0072332: Intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway by p53 class mediator | 1.10E–02 | 3.50E–01 | PERP | PERP, TP53 apoptosis effector |

| 1.90E–01 | PYCARD | PYD and CARD domain containing | ||

| 3.70E–01 | PMAIP1 | phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 | ||

| 4.40E–01 | ZMAT1 | zinc finger matrin-type 1 | ||

| 2.60E–01 | ZNF385D | zinc finger protein 385D | ||

| GO:2000406: Positive regulation of T-cell migration | 4.10E–02 | 1.90E–01 | PYCARD | PYD and CARD domain containing |

| 1.40E–01 | TNFRSF14 | TNF receptor superfamily member 14 | ||

| 2.50E–01 | ITGA4 | integrin subunit alpha 4 | ||

| GO:0002457: T-cell antigen processing and presentation | 9.60E–02 | 3.80E–01 | ICAM1 | intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| 1.30E–01 | RFTN1 | raftlin, lipid raft linker 1 | ||

| GO:0002282: Microglial cell activation involved in immune response | 9.60E–02 | 4.70E–01 | IL33 | interleukin 33 |

| 4.90E–01 | TLR3 | toll like receptor 3 | ||

| GO:0010759: Positive regulation of macrophage chemotaxis | 5.00E–02 | 8.50E–02 | CMKLR1 | chemerin chemokine-like receptor 1 |

| 2.40E–01 | C5AR1 | complement C5a receptor 1 | ||

| 8.50E–02 | TNFSF18 | tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 18 |

Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Downregulation of tumor suppressor genes after irradiation has been described as a major mechanism for GBM cells to enhance their survival [41]. Highlighting the negative association with survival, RNA-seq revealed downregulation of the following representative well-known genes involved in the negative regulation of cell survival: S1PR1, PARP15, HOXA11, and ADGRG1 [42–45]. Improved prognosis in patients with GBMs has been associated with the high expression of S1PR1, suggesting its function as a tumor suppressor [42]. GBMs become less susceptible to radiation and chemotherapy when HOXA11 expression is suppressed [44]. The loss of ADGRG1's function promotes radioresistance of glioma-initiating cells [45].

DISCUSSION

Investigators have shown that irradiation of GBM cells can transform them into a more malignant form [6, 7]. In their transcriptome analysis of glioma, Ma et al. describe that radioresistance of gliomas within hours following irradiation may be due to the inactivation of early proapoptotic molecules and late activation of antiapoptotic genes [41]. It is important to note that in their study, the transcriptome analysis was performed within hours (6–48 hours) following radiation, while in our study, the analysis was done in a stable radioresistant GBM model that we recently developed [8]. Since their study performed analysis within hours following radiation, their findings likely include cells that would not survive radiation long-term. On the other hand, our stable radioresistant GBM model selected out these cells, and our final RNA-seq involved only truly radioresistant cells. Consistent with the Ma et al. study, the aberrant gene expressions observed in irradiated U87-10gy cells were enriched in genes involved in enhancing tumor malignancy and invasion. Similar to the Ma et al. study, we also found upregulation of antiapoptotic genes BNIP3 and SOD2 in irradiated U87-10gy cells. Exclusively enriched in upregulated genes are positive regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, metalloendopeptidase activity genes, and response to hypoxia genes. Upregulated metalloproteases mRNA expressions include MME, MMP2, MMP3, MMP7, MMP12, ADAM9, and ADAM12. Metalloproteases have been strongly implicated in encouraging tumor invasion and metastasis of many cancers by degrading the extracellular protein matrix [21, 22]. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition, a process that overlaps with the acquirement of stem cell properties characterized by increased cell motility and resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy, is an important inducer of cancer stem-like phenotypes and is associated with an aggressive phenotype in glioma [46, 47]. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is typically induced by TGFB3, which was also upregulated in irradiated U87-10gy cells [47, 48]. Hypoxia, which is frequent in GBM, is a major inducer of epithelial to mesenchymal transition as well and is also a main promoter of GBM invasion [47, 49]. In GBM, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) and carbonic anhydrase 9 expressions are induced by hypoxia and promote angiogenesis, migration, cell survival, proliferation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and radio- and chemoresistance [49, 50]. In line with this, we found HIF-1α and carbonic anhydrase 9 expressions upregulated in irradiated U87-10gy cells (Table 2).

Downregulated genes were enriched in tumor suppressor, positive regulation of immune response, P-53 dependent apoptosis, and cell adhesion genes (Tables 1 and 3). On the basis of gene ontology, we uncovered 16 genes associated with apoptosis, 10 genes associated with positive regulation of immune response, and 29 genes associated with cell adhesion that were downregulated (Tables 1 and 3). Ma et al. suggest that suppressing apoptotic potential through gene expression regulation of irradiated cells helps explain the radioresistant nature of irradiated GBM cells [41]. Consistent with our findings, multiple studies have identified downregulation of some of the apoptotic genes discovered in this study to play major roles in attenuating GBM apoptosis, especially for BBC3, DCC, BEX2, CASP1, IL1B, and SFRP2 [51–56]. For example, in their study of GBM cell migration and proliferation, investigators identified BBC3 as a potent inhibitor of cell migration and proliferation in GBM [51]. Downregulation of DCC expression was suggested as an important marker in tumor malignancy and recurrence in astrocytic tumors [52]. To further enhance their survival, GBM cells produce an immunosuppressive microenvironment to escape immune surveillance [57]. One mechanism to achieve this objective is through the secretion of transforming growth factor B (TGF-β) to block T-cell activation and proliferation [57]. In addition to TGF-β, we uncovered many other downregulated genes involved in the activation of the immune system, especially genes mediating T-cell antigen processing and presentation, that may help with immune evasion of radioresistant GBM cells (Tables 2 and 3).

A previous study of our recently described radioresistant GBM model revealed that radiation-induced accumulation of the ASAH1 protein level, as measured by immunoblotting, may enable GBM cells to survive radiation [8, 9]. However, RNA-seq data demonstrated no changes in the mRNA expression of ASAH1 between U87 and U87-10gy cells. This discrepancy can be explained by the reported absence of the high degree of, or even negative correlation (~40% on average), between mRNA and protein expressions [19, 58–62]. Similar mRNA levels can produce varied levels of protein of interest depending on the regulations between the transcripts and protein product such as the ability of the cells to stabilize the mRNA, the rates of translation, the rates of protein degradation, etc. [19, 59, 60]. As seen in this study, irradiation of U87 cells resulted in significant gene expression changes, which may alter post-transcriptional regulation and ultimately affect the resultant protein expression level.

Therapeutically, with the global alterations of multiple biological pathways observed in irradiated GBM cells, an effective GBM therapy may require a cocktail carrying multiple agents targeting multiple implicated pathways in order to have a chance at making a substantial impact on improving the overall GBM survival. These findings of aberrantly expressed mRNAs following irradiation provide a crucial comprehensive starting point to understand the complex mechanism of radioresistance in GBM, and should be combined with immunoblotting or other techniques of direct measurement of protein levels to supply a more accurate picture of how cells can be altered to be radioresistant. Many mRNAs, whose expressions were altered in our radioresistant GBM model, have never before been reported to be associated with the development of radioresistant GBM and should be further investigated to understand their roles in radioresistance.

The absence of a major progress in the treatment of GBM is partly attributable to our poor understanding of both GBM tumor biology and the acquirement of treatment resistance in recurrent GBMs. Recurrent GBMs are characterized by their resistance to radiation. In this study, we used an established stable radioresistant GBM model to shed light on global mRNA expression changes after irradiation. Many mRNAs, the expressions of which were altered in our radioresistant U87 GBM model, have never before been reported to be associated with the development of radioresistant GBMs and should be concertedly further investigated to understand their roles in radioresistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and cells

The U87 and U87-10gy glioblastoma cell lines were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum. Culture medium materials were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY, USA).

RNA library preparation and sequencing

RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer`s protocol. The RNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Integrity was assessed using an Agilent 2200 TapeStation instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, polyA mRNA from an input of 500 ng high-quality total RNA (RINe>8) was purified and fragmented. First strand complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) syntheses were performed at 25° C for 10 minutes, 42° C for 15 minutes, and 70° C for 15 minutes, using random hexameres and ProtoScript II Reverse Transcriptase (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). In a second strand cDNA synthesis, the RNA templates were removed and a second replacement strand was generated by incorporating deoxyuridine triphosphate (in place of deoxythymidine triphosphate, to keep strand information) to generate ds cDNA. The blunt-ended cDNA was cleaned up from the second strand reaction mix with beads. Next, the 3′ ends of the cDNA were adenylated and then indexing adaptors were ligated. Polymerase chain reactions (15 cycles of 98° C for 10 seconds, 60° C for 30 seconds, and 72° C for 30 seconds) were used to selectively enrich those DNA fragments that have adapter molecules on both ends and to amplify the amount of DNA in the library.

The libraries were quantified using the Promega QuantiFluor dsDNA System on a Quantus Fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI). The size and purity of the libraries were analyzed using the High Sensitivity D1000 Screen Tape on an Agilent 2200 TapeStation instrument. The libraries were normalized, pooled, and subjected to cluster, and pair read sequencing was performed for 150 cycles on a HiSeq4000 instrument (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Generation of the stable radioresistant GBM model

The method and detail to generate the stable radioresistant GBM model was previously described by us [8]. U87 cell lines were grown to confluence and then irradiated with a Pantak HF320 X-ray machine (Agfa NDT Ltd., Reading, UK) operating at 300 kV at a dosage of 2.09 Gy/min to a total radiation dose of 10 Gy, to generate the U87-10gy cell lines. Following radiation, these irradiated cells were allowed to recover and to grow to confluence. The U87-10gy cell line was stable for continued passages for further studies.

Gene ontology analysis

The gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.7, NIAIS/NIH (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). The heatmap was performed with a web-based program (http://www.heatmapper.ca/expression).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLES

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lydia Washechek of the Center for Imaging Research for editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ASAH1

Acid cermadise

- cDNA

Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- GBM

Giloblastoma

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- mRNA

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- SIP

Sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SPHK1

Sphingosine kinase 1

- SPHK2

Sphingosine kinase 2

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor B

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

FUNDING

Musella Foundation Grant, Department of Neurosurgery Larson Endowment Grant

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, Stroup NE, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006-2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:ii1–56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, Liu M, Blanda R, Kromer C, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008-2012. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Rouse C, Chen Y, Dowling J, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan J. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2007-2011. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:iv1–iv63. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander BM, Cloughesy TF. Adult Glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2402–2409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou LC, Veeravagu A, Hsu AR, Tse VC. Recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a review of natural history and management options. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong ET, Hess KR, Gleason MJ, Jaeckle KA, Kyritsis AP, Prados MD, Levin VA, Yung WK. Outcomes and prognostic factors in recurrent glioma patients enrolled onto phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2572–2578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doan NB, Nguyen HS, Al-Gizawiy MM, Mueller WM, Sabbadini RA, Rand SD, Connelly JM, Chitambar CR, Schmainda KM, Mirza SP. Acid ceramidase confers radioresistance to glioblastoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;38:1932–1940. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doan NB, Nguyen HS, Montoure A, Al-Gizawiy MM, Mueller WM, Kurpad S, Rand SD, Connelly JM, Chitambar CR, Schmainda KM, Mirza SP. Acid ceramidase is a novel drug target for pediatric brain tumors. Oncotarget. 2017;8:24753–24761. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15800. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogretmen B, Hannun YA. Biologically active sphingolipids in cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:604–616. doi: 10.1038/nrc1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taha TA, Mullen TD, Obeid LM. A house divided: ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate in programmed cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:2027–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckham TH, Lu P, Cheng JC, Zhao D, Turner LS, Zhang X, Hoffman S, Armeson KE, Liu A, Marrison T, Hannun YA, Liu X. Acid ceramidase-mediated production of sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes prostate cancer invasion through upregulation of cathepsin B. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2034–2043. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernardo K, Hurwitz R, Zenk T, Desnick RJ, Ferlinz K, Schuchman EH, Sandhoff K. Purification, characterization, and biosynthesis of human acid ceramidase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11098–11102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferlinz K, Kopal G, Bernardo K, Linke T, Bar J, Breiden B, Neumann U, Lang F, Schuchman EH, Sandhoff K. Human acid ceramidase: processing, glycosylation, and lysosomal targeting. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35352–35360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JH, Schuchman EH. Acid ceramidase and human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:2133–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosch S, Schiffmann S, Geisslinger G. Chain length-specific properties of ceramides. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettus BJ, Chalfant CE, Hannun YA. Ceramide in apoptosis: an overview and current perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585:114–125. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa-Silva J, Domingues D, Lopes FM. RNA-Seq differential expression analysis: An extended review and a software tool. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0190152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koussounadis A, Langdon SP, Um IH, Harrison DJ, Smith VA. Relationship between differentially expressed mRNA and mRNA-protein correlations in a xenograft model system. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10775. doi: 10.1038/srep10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindemann C, Marschall V, Weigert A, Klingebiel T, Fulda S. Smac Mimetic-Induced Upregulation of CCL2/MCP-1 Triggers Migration and Invasion of Glioblastoma Cells and Influences the Tumor Microenvironment in a Paracrine Manner. Neoplasia. 2015;17:481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown GT, Murray GI. Current mechanistic insights into the roles of matrix metalloproteinases in tumour invasion and metastasis. J Pathol. 2015;237:273–281. doi: 10.1002/path.4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang SL, Kuo FH, Chen PN, Hsieh YH, Yu NY, Yang WE, Hsieh MJ, Yang SF. Andrographolide suppresses the migratory ability of human glioblastoma multiforme cells by targeting ERK1/2-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression. Oncotarget. 2017;8:105860–105872. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22407. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai A, Kharbanda S, Pope WB, Tran A, Solis OE, Peale F, Forrest WF, Pujara K, Carrillo JA, Pandita A, Ellingson BM, Bowers CW, Soriano RH, et al. Evidence for sequenced molecular evolution of IDH1 mutant glioblastoma from a distinct cell of origin. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4482–4490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan YB, Zhang CH, Wang SQ, Ai PH, Chen K, Zhu L, Sun ZL, Feng DF. Transforming growth factor beta induced (TGFBI) is a potential signature gene for mesenchymal subtype high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2018;137:395–407. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2729-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton TR, Eisenstat DD, Gibson SB. BNIP3 (Bcl-2 19 kDa interacting protein) acts as transcriptional repressor of apoptosis-inducing factor expression preventing cell death in human malignant gliomas. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4189–4199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5747-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang SX, Zhao ZY, Weng GH, He XY, Wu CJ, Fu CY, Sui ZY, Ma YS, Liu T. Upregulation of miR-181a suppresses the formation of glioblastoma stem cells by targeting the Notch2 oncogene and correlates with good prognosis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner KM, Sun Y, Ji P, Granberg KJ, Bernard B, Hu L, Cogdell DE, Zhou X, Yli-Harja O, Nykter M, Shmulevich I, Yung WK, Fuller GN, et al. Genomically amplified Akt3 activates DNA repair pathway and promotes glioma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3421–3426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414573112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haemmig S, Baumgartner U, Gluck A, Zbinden S, Tschan MP, Kappeler A, Mariani L, Vajtai I, Vassella E. miR-125b controls apoptosis and temozolomide resistance by targeting TNFAIP3 and NKIRAS2 in glioblastomas. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1279. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen RD, Gajjar MK, Tuckova L, Jensen KE, Maya-Mendoza A, Holst CB, Mollgaard K, Rasmussen JS, Brennum J, Bartek J, Jr, Syrucek M, Sedlakova E, Andersen KK, et al. BRCA1-regulated RRM2 expression protects glioblastoma cells from endogenous replication stress and promotes tumorigenicity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13398. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruyere C, Mijatovic T, Lonez C, Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Berger W, Kast RE, Ruysschaert JM, Kiss R, Lefranc F. Temozolomide-induced modification of the CXC chemokine network in experimental gliomas. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1453–1464. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maachani UB, Shankavaram U, Kramp T, Tofilon PJ, Camphausen K, Tandle AT. FOXM1 and STAT3 interaction confers radioresistance in glioblastoma cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:77365–77377. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12670. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou YC, Chang MY, Wang MJ, Yu FS, Liu HC, Harnod T, Hung CH, Lee HT, Chung JG. PEITC inhibits human brain glioblastoma GBM 8401 cell migration and invasion through the inhibition of uPA, Rho A, and Ras with inhibition of MMP-2, -7 and -9 gene expression. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:2489–2496. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dikshit B, Irshad K, Madan E, Aggarwal N, Sarkar C, Chandra PS, Gupta DK, Chattopadhyay P, Sinha S, Chosdol K. FAT1 acts as an upstream regulator of oncogenic and inflammatory pathways, via PDCD4, in glioma cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:3798–3808. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghosh D, Ulasov IV, Chen L, Harkins LE, Wallenborg K, Hothi P, Rostad S, Hood L, Cobbs CS. TGFbeta-Responsive HMOX1 Expression Is Associated with Stemness and Invasion in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Stem Cells. 2016;34:2276–2289. doi: 10.1002/stem.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banasavadi-Siddegowda YK, Russell L, Frair E, Karkhanis VA, Relation T, Yoo JY, Zhang J, Sif S, Imitola J, Baiocchi R, Kaur B. PRMT5-PTEN molecular pathway regulates senescence and self-renewal of primary glioblastoma neurosphere cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:263–274. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensen SA, Calvert AE, Volpert G, Kouri FM, Hurley LA, Luciano JP, Wu Y, Chalastanis A, Futerman AH, Stegh AH. Bcl2L13 is a ceramide synthase inhibitor in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5682–5687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316700111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapitonov D, Allegood JC, Mitchell C, Hait NC, Almenara JA, Adams JK, Zipkin RE, Dent P, Kordula T, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting sphingosine kinase 1 inhibits Akt signaling, induces apoptosis, and suppresses growth of human glioblastoma cells and xenografts. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6915–6923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fedele V, Dai F, Masilamani AP, Heiland DH, Kling E, Gatjens-Sanchez AM, Ferrarese R, Platania L, Soroush D, Kim H, Nelander S, Weyerbrock A, Prinz M, et al. Epigenetic Regulation of ZBTB18 Promotes Glioblastoma Progression. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:998–1011. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, Xu X, Liu N, Cheng Y, Jin W, Zhang P, Wang X, Yang H, Liu H, Tu Y. SOX9-PDK1 axis is essential for glioma stem cell self-renewal and temozolomide resistance. Oncotarget. 2018;9:192–204. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22773. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu L, Li X, Liu Q, Xu J, Ge H, Wang Z, Wang H, Wang Z, Shi C, Xu X, Huang J, Lin Z, Pieper RO, et al. UBE2S, a novel substrate of Akt1, associates with Ku70 and regulates DNA repair and glioblastoma multiforme resistance to chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2017;36:1145–1156. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H, Rao L, Wang HL, Mao ZW, Lei RH, Yang ZY, Qing H, Deng YL. Transcriptome analysis of glioma cells for the dynamic response to gamma-irradiation and dual regulation of apoptosis genes: a new insight into radiotherapy for glioblastomas. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e895. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahajan-Thakur S, Bien-Moller S, Marx S, Schroeder H, Rauch BH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) signaling in glioblastoma multiforme-A systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017. p. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Guerrero-Preston R, Michailidi C, Marchionni L, Pickering CR, Frederick MJ, Myers JN, Yegnasubramanian S, Hadar T, Noordhuis MG, Zizkova V, Fertig E, Agrawal N, Westra W, et al. Key tumor suppressor genes inactivated by “greater promoter” methylation and somatic mutations in head and neck cancer. Epigenetics. 2014;9:1031–1046. doi: 10.4161/epi.29025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Se YB, Kim SH, Kim JY, Kim JE, Dho YS, Kim JW, Kim YH, Woo HG, Kim SH, Kang SH, Kim HJ, Kim TM, Lee ST, et al. Underexpression of HOXA11 Is Associated with Treatment Resistance and Poor Prognosis in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:387–398. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreno M, Pedrosa L, Pare L, Pineda E, Bejarano L, Martinez J, Balasubramaniyan V, Ezhilarasan R, Kallarackal N, Kim SH, Wang J, Audia A, Conroy S, et al. GPR56/ADGRG1 Inhibits Mesenchymal Differentiation and Radioresistance in Glioblastoma. Cell Rep. 2017;21:2183–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zarkoob H, Taube JH, Singh SK, Mani SA, Kohandel M. Investigating the link between molecular subtypes of glioblastoma, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and CD133 cell surface protein. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwadate Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma progression. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1615–1620. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye XZ, Xu SL, Xin YH, Yu SC, Ping YF, Chen L, Xiao HL, Wang B, Yi L, Wang QL, Jiang XF, Yang L, Zhang P, et al. Tumor-associated microglia/macrophages enhance the invasion of glioma stem-like cells via TGF-beta1 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2012;189:444–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monteiro AR, Hill R, Pilkington GJ, Madureira PA. The Role of Hypoxia in Glioblastoma Invasion. Cells. 2017. p. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Proescholdt MA, Merrill MJ, Stoerr EM, Lohmeier A, Pohl F, Brawanski A. Function of carbonic anhydrase IX in glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:1357–1366. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang D, Li Y, Wang R, Li Y, Shi P, Kan Z, Pang X. Inhibition of REST Suppresses Proliferation and Migration in Glioblastoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016. p. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Nakatani K, Yoshimi N, Mori H, Sakai H, Shinoda J, Andoh T, Sakai N. The significance of the expression of tumor suppressor gene DCC in human gliomas. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:237–242. doi: 10.1023/a:1006114328134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang X, Yoon JG, Li L, Yu W, Shao J, Hua D, Zheng S, Hood L, Goodlett DR, Foltz G, Lin B. The SOX2 response program in glioblastoma multiforme: an integrated ChIP-seq, expression microarray, and microRNA analysis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng J, Yan PF, Zhao HY, Zhang FC, Zhao WH, Feng M. Inhibitor of Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase Sensitizes Glioblastoma Cells to Temozolomide via Activating ROS/JNK Signaling Pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1450843. doi: 10.1155/2016/1450843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baysan M, Woolard K, Cam MC, Zhang W, Song H, Kotliarova S, Balamatsias D, Linkous A, Ahn S, Walling J, Belova GI, Fine HA. Detailed longitudinal sampling of glioma stem cells in situ reveals Chr7 gain and Chr10 loss as repeated events in primary tumor formation and recurrence. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:2002–2013. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stricker SH, Feber A, Engstrom PG, Caren H, Kurian KM, Takashima Y, Watts C, Way M, Dirks P, Bertone P, Smith A, Beck S, Pollard SM. Widespread resetting of DNA methylation in glioblastoma-initiating cells suppresses malignant cellular behavior in a lineage-dependent manner. Genes Dev. 2013;27:654–669. doi: 10.1101/gad.212662.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Razavi SM, Lee KE, Jin BE, Aujla PS, Gholamin S, Li G. Immune Evasion Strategies of Glioblastoma. Front Surg. 2016;3:11. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Sousa Abreu R, Penalva LO, Marcotte EM, Vogel C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:1512–1526. doi: 10.1039/b908315d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:227–232. doi: 10.1038/nrg3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maier T, Guell M, Serrano L. Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3966–3973. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenbaum D, Colangelo C, Williams K, Gerstein M. Comparing protein abundance and mRNA expression levels on a genomic scale. Genome Biol. 2003;4:117. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huber M, Bahr I, Kratzschmar JR, Becker A, Muller EC, Donner P, Pohlenz HD, Schneider MR, Sommer A. Comparison of proteomic and genomic analyses of the human breast cancer cell line T47D and the antiestrogen-resistant derivative T47D-r. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:43–55. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300047-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.