ABSTRACT

Galleria mellonella is a well-accepted insect model for the study of pathogen-host interactions and antimicrobial compounds. The main advantages of this model include the low cost of maintenance, the fast life cycle, the possibility of using a large number of caterpillars and the innate immune system, which is evolutionarily conserved relative to mammals. Because of these advantages, different research groups have been working to implement the rearing of G. mellonella in laboratory conditions. This protocol describes our experience in the rearing of G. mellonella caterpillars for experimental infection models and the influence of different artificial diets on developmental and physiological parameters. Here, we suggest a diet composition that benefits the life cycle of G. mellonella by accelerating the larval phase length and increasing the caterpillar weight. This diet also stimulated the immune system of G. mellonella by increasing the hemolymph volume and hemocyte concentration. In addition, our rearing protocol generated caterpillars that are more resistant to infection by Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Candida albicans. A standard G. mellonella rearing protocol is fundamental to minimize external influences on the results, and this simple and easy protocol can support researchers starting to rear G. mellonella.

KEYWORDS: experimental model, Galleria mellonella, in vivo study, rearing

Introduction

Mammalian models are the gold standard for in vivo assays; however, ethical problems, high cost and specialized training requirements have led scientists to develop alternatives for in vivo experimentation. The greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, has been well-accepted by the scientific community as an experimental model for infection with different bacterial and fungal species.1–8 This model provides useful information on virulence mechanisms, pathogenesis, and antimicrobial efficacy.4,9–11 In the last few decades, studies have shown a positive correlation between results obtained in G. mellonella and mammalian models.12–15 Furthermore, this insect model has numerous advantages over other in vivo models, such as low cost, the possibility of large-scale breeding, the speed and ease of test execution and interpretation, the ability to incubate caterpillars at temperatures between 25°C and 37°C and the evolutionary conservation relative to mammals.16,17 Another advantage of the G. mellonella model is the multiple options available for the facile inoculation of the pathogen.18,19 Most studies introduce the infection by injecting a standardized microbial inoculum;20 however, the infection can also be performed via ingestion or oral delivery.21

Galleria mellonella has a wide geographic distribution and lives naturally in beehives, causing serious problems for the apicultural industry.22 This insect has four developmental stages: egg, caterpillar, pre-pupae/pupa and adult insect (Fig. 1). The eggs are white to light pink in color and take between 5 and 8 days (24-27°C) to develop and became caterpillars. The caterpillars are creamy-white and measure 1–23 mm.22,23 This stage takes 6–7 weeks at 28–32°C. During this time, caterpillars undergo 8–10 molting stages and spin silk threads across all stages, but only the last instar spins a cocoon.22,23 When the caterpillar ceases feeding and still presents some motility, during the formation of the coccon, characterizes the intermediate stage of the pre-pupae.24 Next, the caterpillars became pupae, which are dark reddish brown and immobilized in cocoons. From pupa to moth takes 1 to 8 weeks, and the insect does not eat throughout this time. Moths are a reddish brown and pale cream color, are active during the night and are able to lay 50–150 eggs.22,23,25,26 Male moths are slightly smaller and lighter in color than females. Additionally, female moths present a bifurcated proboscis and a labial palps projecting forward (beak-like appearance).26 Therefore, the labial palps are peaked in females and rounded in males (Fig. 2). The entire life cycle takes approximately 40 days depending on environmental conditions like temperature and food supply.22,23,25,26

Figure 1.

Different developmental stages of Galleria mellonella. Eggs (1), approximately 10-day-old caterpillar (2), approximately 20-day-old caterpillar (3), 25-35-day-old caterpillar (4 and 5), approximately 40-day-old caterpillar (last larval stage) (6), pre-pupae and pupae (7 and 8), adult moths (9).

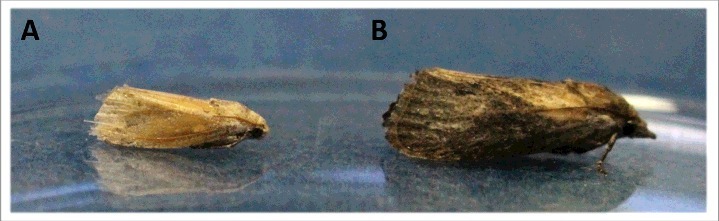

Figure 2.

Galleria mellonella male (A) and female (B).

The caterpillars of this insect obtain nutrients naturally from honey, pupal skins, pollen and beeswax.27 However, the use of a poor artificial diet can cause developmental problems and sometimes death. Previous studies compared natural diets and artificial diets from different sources for G. mellonella rearing and evaluated biological parameters like larval weight, larval phase duration, pupal weight and duration, longevity, egg productivity, immunity and others.22,27–29 Here, we suggest a diet that provides G. mellonella a short life cycle, an increase in hemolymph volume and hemocyte concentration, and a higher caterpillar survival when compared to other diets. Since G. mellonella is a well-accepted infection model, there is increasing motivation for the use of this alternative animal; however, depending on the country, the availability of these caterpillars for purchase for experimentation is limited. Based on this, research centers have started rearing G. mellonella. This study aims to develop a protocol for G. mellonella rearing and to establish a diet that will provide better development of caterpillars in order to obtain a standardized model for future microbiological research.

Materials

Reagents

-

•

Brain-heart Infusion Broth (BHI, Difco)

-

•

Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (SDB, Difco)

-

•

Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

-

•

Glass or plastic containers with holes in the cover (Moths cage)

-

•

Plastic or metal containers with holes in the cover (Caterpillar's cage)

-

•

Cloth-type voile

-

•

Cardboard

-

•

Filter paper

-

•

Spatula

-

•

Diet components described in Table 1

-

•

Wax blocks

Table 1.

Dietary components evaluated for Galleria mellonella rearing.

| Diet 1 | Diet 2 | Diet 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 20 g of brown sugar | 300 g oat flakes | 250 g of corn meal |

| 80 g of glycerol | 300 g of whole wheat flour | 150 g of yeast extract |

| 400 g of powder milk | 60 g dried yeast | 100 g of soy flour |

| 120 g yeast extract | 120 mL of glycerol | 100 g of powder milk |

| 200 g of whole wheat flour | 120 ml of honey | 200 g of honey |

| 200 g of wheat bran | beeswax blocks | 200 g of glycerol |

| 200 g of wheat germ | beeswax blocks | |

| beeswax blocks |

Equipament

-

•

Incubator (BOD, Eletrolab)

-

•

Hamilton syringes (10 μL capacity, Reno)

-

•

Scale (Sartorius)

-

•

Centrifuge (MPW-350)

-

•

Automatic Cell Counter (Countess® Automated Cell Counter-Invitrogen)

-

•

Spectrophotometer (B582, Micronal)

Methods

To initiate G. mellonella rearing in the laboratory of Microbiology and Immunology at the Institute of Science and Technology (ICT/Unesp/Brazil), we acquired some caterpillars from Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (Embrapa, Juiz de Fora, Brazil) that were kindly provided by Dr. Marcia Prata. The caterpillars were fed with 3 different artificial diets of high nutritional quality as described in Table 1. To prepare diets 1, 2 and 3, all components were weighed and mixed well using a spatula. Pieces of wax blocks were added to supplement the diet. The compositions of diets 2 and 3 were based on the protocol described by Mead et al.30 and Brighenti et al.,31 respectively.

Procedure of Galleria mellonella rearing

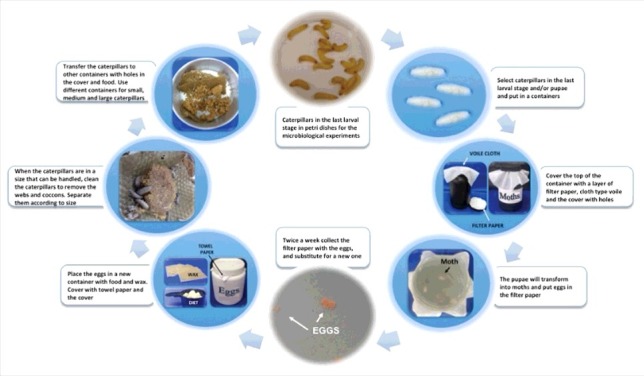

For G. mellonella rearing, we established a detailed protocol (Fig. 3) that covers all life stages of this insect model as follows:

Figure 3.

Process for Galleria mellonella rearing.

-

(1)

A total of 10 to 30 caterpillars in the last larval stage (and/or already pupae) were placed in plastic/glass containers (+/− 30 cm high) with holes in the covers. CAUTION: Use dark containers or protect the containers from light. There is no need to add an exact number of male or female moths. Male moths can fertilize multiple females; moreover, the number of eggs that females lay is high.

-

(2)

To support egg-laying, a layer of filter paper was placed in the top of the container followed by a piece of cloth-type voile. The containers were incubated at room temperature for 1–3 weeks until most of the moths became old or died. CAUTION: Although pupae and moths do not need to be fed, a little food should be added inside the container to avoid the starvation of very small caterpillars that could appear before egg removal.

-

(3)

Twice a week, the filter paper with the eggs was replaced with a new one. The removed filter paper was transferred to a plastic container with a cover with several holes. A paper towel was placed between the cover and the container to prevent small caterpillars from getting out, and wax and food were provided. The egg containers were incubated at 28°C for approximately 20 days and checked once a week to monitor the caterpillar growth. CAUTION: Eggs are very sensitive and may burst if pressed; extreme care is needed when transferring the eggs.

-

(4)

After 20 days, when the caterpillars have reached a sufficient size to be handled (approximately 1 cm), the container was cleaned to remove the webs and cocoons. Then, the caterpillars were separated according to size (small, medium and large, respectively, with 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 cm) and transferred to containers with holes in the covers and food. The caterpillars were maintained at 28°C.

Experimental design

Evaluation of the effects of nutritious diets on the development of G. mellonella caterpillars

To evaluate the effects of diets on the life cycle of G. mellonella, 250 eggs were monitored daily to determine the larval phase duration (period from egg to the last larval stage) and the percentage of pupae. Moreover, to study the effects of diet on weight, 30 caterpillars fed different diets were monitored daily.

Evaluation of nutritious diets on the physiology of G. mellonella caterpillars

For this analysis, we determined the hemolymph volume and hemocytic density of each G. mellonella caterpillar. The hemolymph was collected as described by Harding et al.32 using a pre-chilled Eppendorf tube to avoid the clotting process. The volume of hemolymph collected was measured with a micropipette. To measure hemocytic density, the number of cells in the hemolymph was estimated by counting viable cells using Trypan blue in an Automatic Cell Counter.

Evaluation of the effects of nutritious diets on the response of G. mellonella to infections with S. aureus, E. coli and C. albicans

The susceptibility of G. mellonella caterpillars to microbial infection was determined with survival curve assays. Initially, a standardized suspension containing 108 cells/mL was prepared for each strain of microorganism: S. aureus ATCC 6538, E. coli ATCC 25922 and C. albicans ATCC 18804. The caterpillars were infected with each microorganism and incubated at 37°C. The survival rate was monitored 18 h post-infection and subsequently every 24 h for the next 7 days. The caterpillars were considered dead when there was no movement after being touched with forceps.

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla CA, USA), and statistics were generated with ANOVA and Tukey's post-test. The survival curves were analyzed by the Log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). The significance level adopted in all analyzes was P < 0.05.

Antecipated results

Initially, the parameters of the life cycle of caterpillars fed with three different diets were evaluated (Table 2). Diets 1 and 2 increased Galleria mellonella larval stage approximately 10 days when compared to the groups fed diet 3. The caterpillar weights in the three different diet groups were compared as well and there were no significant differences between the weights of the caterpillars fed with diet 1 or diet 2. However, the weights of the caterpillars fed with diet 3 were higher than the weights of either other group. The analysis of the influence of diet on pupae formation demonstrated that caterpillars fed with diet 1 had a significantly higher percent pupae formation than the other two groups. The lowest percentage of pupae formation was observed in the group fed diet 2.

Table 2.

Larval life cycle parameters of Galleria mellonella groups fed different diets.

| Diet | Larval phase (days) | Weight (g) | Pulpal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet 1 | 42 ± 1.53a | 0.277 ± 0.031a | 15.2 ± 1.70a |

| Diet 2 | 49 ± 2.52b | 0.278 ± 0.019a | 4 ± 1.29b |

| Diet 3 | 35 ± 2.00c | 0.365 ± 0.033b | 8.4 ± 0.84c |

Mean values and standard deviations (±SD) of three independent experiments are represented. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences among the groups, according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05).

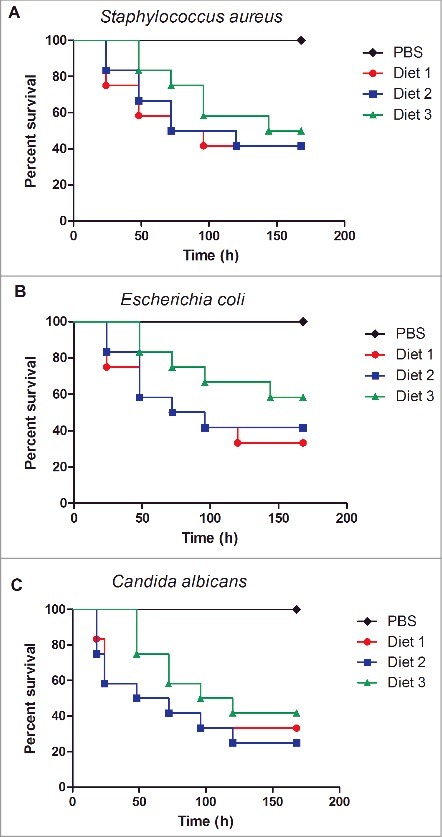

The physiological parameters of G. mellonella fed different diets were also evaluated. The hemolymph volume and hemocyte density of caterpillars fed diet 3 showed higher values compared to the groups fed diets 1 and 2 (Table 3). The survival rates of caterpillars infected with S. aureus, E. coli and C. albicans are also shown in Table 3. Although no significant difference among the groups for any of the microorganisms studied was observed, the greatest survival rates were found in the groups fed diet 3 (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Immune system parameters of Galleria mellonella groups fed different diets.

| Survival (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | Hemolymph volume (µL) | Hemocyte concentrations (x106/mL) | S. aureus | E. coli | C. albicans |

| Diet 1 | 20 ± 4.57a | 2.4 ± 0.29a | 41.67 | 33.33 | 33.33 |

| Diet 2 | 23 ± 5.29a | 2.8 ± 0.17a | 41.67 | 41.67 | 25.00 |

| Diet 3 | 48 ± 4.20b | 5.7 ± 0.43b | 50.00 | 58.33 | 41.67 |

Mean values and standard deviations (±SD) of three independent experiments are represented. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences among the groups, according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Survival curves of Galleria mellonella fed different diets and infected with Staphylococcus aureus (A), Escherichia coli (B) and Candida albicans (C). No significant difference was observed among the groups fed diets 1, 2 or 3 for each microorganism: S. aureus (P = 0.7367), E. coli (P = 0.4010), and C. albicans (P = 0.5027).

Discussion and problem handling

This study aimed to establish a protocol for G. mellonella rearing that could generate caterpillars to be used as model hosts for experimental infections. It is known that some protocol characteristics are crucial to obtain a culture of G. mellonella with good developmental cycles and the ability to generate a large number of healthy and active caterpillars. Therefore, we tested three different diets for feeding G. mellonella caterpillars, evaluated their development, physiological characteristics and response to infections.

To evaluate the development of G. mellonella, we measured the duration of the larval phase and the weight of caterpillars at the last instar. We noticed that caterpillars fed with diet 3 exhibited a shorter larval phase and a higher weight compared to those fed diets 1 and 2. Diet quality has been demonstrated to affect the development of caterpillars, and suitable diets require different nutrients, such as carbohydrates, protein and lipids.26,29 A weak diet results in a long life cycle with a short oviposition period and a lengthy egg incubation period.27 In our study, the composition of diet 3 was the most appropriate to obtain a short larval phase and, consequently, to generate healthier caterpillars. A fast life cycle has been correlated with the ability to grow and reproduce.33

In the analysis of the development of G. mellonella, we also quantified the percentage of pupae formed. Since we observed a shorter larval phase on diet 3, we expected to find a greater percentage of pupae with this diet. However, diet 3 resulted in 8.4% of pupa being formed, which was between the groups fed diet 1 (15.2%) and diet 2 (4%). Intraspecific factors, such as competition for food and cannibalism (of vulnerable early instars and late instars), may have affected the survival of caterpillars.26

In addition to the diet, temperature and relative humidity are also crucial to the entire life cycle of G. mellonella. According to different authors, a temperature range of 25–33°C, as used in our study, ensures an adequate length of the G. mellonella life cycle.22,23,25,34 However, we did not monitor humidity during our experiments. Kwada et al.26 reported that a humidity average of 29–33% appears appropriate for the development of the G. mellonella life cycle.

In this study, we also considered an adequate diet one that resulted in caterpillars with suitable amounts of hemolymph and hemocyte concentrations for in vivo experimentation. Among the different diets tested, individuals in the diet 3 group had the highest hemolymph volume and concentration of hemocytes. The hemolymph of G. mellonella is responsible for substance and nutrient transport and is composed of six types of hemocytes (prohemocytes, plasmatocytes, granulocytes, coagulocytes, spherulocytes and oenocytoids) with different functions, including phagocytosis.35 These hemocytes are responsible for cellular immune responses in G. mellonella, such as nodule formation and encapsulation.35 Therefore, our results proved that the composition of diet has a significant effect on the G. mellonella immune system. The influence of diet on the insect immune system was also reported by Siva-Jothy e Thompson36 who found that food deprivation can decrease the immune response activity. In another study, Krams et al.28 demonstrated that the composition of the diet is related to immune system activity. A very high-energy diet can promote the fast development of body weight, but the immune system can have several deficiencies. Maturation is necessary for the immune system to increase the metabolism of caterpillars.28 This fact emphasizes the importance of standardizing the diets during the development of G. mellonella caterpillars to promote inter-laboratory comparisons.

In addition, we evaluated the susceptibility of caterpillars to infection with different microorganisms, since this assay gives information important for microbiological studies. For all the diets tested in our study, it was possible to monitor the infection process up to 7 days, including the infections induced by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as a fungal pathogen. According to Champion et al.,37 in the G. mellonella infection model, the survival rate needs to be monitored for up to 5 days post-infection to allow for the calculation of a maximum half lethal dose. In this study, we verified that the survival of caterpillars infected with bacteria and yeast increased 8–25% when they were fed with diet 3 relative to diets 1 and 2. It is known that nutrition is an important parameter to be considered for rearing G. mellonella for microbiological studies.38 Banville et al.38 demonstrated that starvation before experimentation could decrease microorganism susceptibility because it causes immune response depletion. Therefore, our results suggested that diet 3 activates the immune response of G. mellonella and makes this insect more resistant to infection by bacteria and yeast.

In summary, the protocol described here is simple, easy and can support the rearing of G. mellonella. Additional questions and tips can be found in the Table 4. According to our results, diet 3 showed the best condition for rearing G. mellonella for microbiological studies because this diet provided a short life cycle, increased caterpillar weight and immune system activation. In addition to the physiological benefits, the ingredients for this diet are easy to purchase, and the diet is inexpensive and easy to prepare. Based on this, the standardization of parameters related to rearing as well as the protocol for in vivo experimentation can improve inter-laboratory comparisons and provide reliable results for experiments using G. mellonella.

Table 4.

Questions and tips for Galleria mellonella rearing.

| Questions | Solution and tips |

|---|---|

| How many times should G. mellonella be fed? | Every two or three days is enough. |

| How much food should be added? | For egg/small larvae container put 5g of food and for median/large 8–10g. |

| How the just born larvae looks like? | Just born larvae are white and very small (around 1mm). |

| How to prevent very small larvae from escaping of the moth container? | Change the filter paper with the eggs more often. |

| How many male and female moths are necessary for egg position? | There is no need to add an exact number of male or female moths. Male moths can fertilize multiple females; moreover, the number of eggs that females lay is high. |

| How can the eggs be removed from the filter paper? | It is not necessary to remove the eggs from the filter paper because they are very sensitive. Transfer the paper with the eggs as described. |

Funding Statement

São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) ID: 2015/09770-9

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following Brazilian organizations: The Fundação de Apoio á Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) 2015/09770-9 and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

References

- 1.Scorzoni L, de Lucas MP, Mesa-Arango AC, Fusco-Almeida AM, Lozano E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Mendes-Giannini MJ, Zaragoza O. Antifungal efficacy during Candida krusei infection in non-conventional models correlates with the yeast in vitro susceptibility profile. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achterman RR, Smith AR, Oliver BG, White TC. Sequenced dermatophyte strains: growth rate, conidiation, drug susceptibilities, and virulence in an invertebrate model. Fungal Genet Biol. 2011;48:335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Junqueira JC. Galleria mellonella as a model host for human pathogens: recent studies and new perspectives. Virulence. 2012;3:474–6. doi: 10.4161/viru.22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-Rodas R, Casadevall A, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M, Zaragoza O. Cryptococcus neoformans capsular enlargement and cellular gigantism during Galleria mellonella infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diago-Navarro E, Chen L, Passet V, Burack S, Ulacia-Hernando A, Kodiyanplakkal RP, Levi MH, Brisse S, Kreiswirth BN, Fries BC. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibit variability in capsular polysaccharide and capsule associated virulence traits. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:803–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alghoribi MF, Gibreel TM, Dodgson AR, Beatson SA, Upton M. Galleria mellonella infection model demonstrates high lethality of ST69 and ST127 uropathogenic E. coli. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mylonakis E, Moreno R, El Khoury JB, Idnurm A, Heitman J, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM, Diener A. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3842–50. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3842-3850.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman JJ, Muhammed M, Kasperkovitz PV, Vyas JM, Mylonakis E. Fusarium pathogenesis investigated using Galleria mellonella as a heterologous host. Fungal Biol. 2011;115:1279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mesa-Arango AC, Forastiero A, Bernal-Martínez L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Mellado E, Zaragoza O. The non-mammalian host Galleria mellonella can be used to study the virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis and the efficacy of antifungal drugs during infection by this pathogenic yeast. Med Mycol. 2013;51:461–72. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.737031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lacorte Singulani J, Scorzoni L, de Paula E Silva AC, Fusco-Almeida AM, Mendes-Giannini MJ. Evaluation of the efficacy of antifungal drugs against Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii in a Galleria mellonella model. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benaducci T, Sardi JeC, Lourencetti NM, Scorzoni L, Gullo FP, Rossi SA, Derissi JB, de Azevedo Prata MC, Fusco-Almeida AM, Mendes-Giannini MJ. Virulence of Cryptococcus sp. Biofilms In Vitro and In Vivo using Galleria mellonella as an alternative model. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:290. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sangalli-Leite F, Scorzoni L, Alves de Paula E, Silva AC, da Silva JF, de Oliveira HC, de Lacorte Singulani J, Gullo FP, Moraes da Silva R, Regasini LO, et al.. Synergistic effect of pedalitin and amphotericin B against Cryptococcus neoformans by in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48:504–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunke S, Quintin J, Kasper L, Jacobsen ID, Richter ME, Hiller E, Schwarzmüller T, d'Enfert C, Kuchler K, Rupp S, et al.. Of mice, flies–and men? Comparing fungal infection models for large-scale screening efforts. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:473–86. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desalermos A, Tan X, Rajamuthiah R, Arvanitis M, Wang Y, Li D, Kourkoumpetis TK, Fuchs BB, Mylonakis E. A multi-host approach for the systematic analysis of virulence factors in Cryptococcus neoformans. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:298–305. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brennan M, Thomas DY, Whiteway M, Kavanagh K. Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;34:153–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mylonakis E. Galleria mellonella and the study of fungal pathogenesis: making the case for another genetically tractable model host. Mycopathologia. 2008;165:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arvanitis M, Glavis-Bloom J, Mylonakis E. Invertebrate models of fungal infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1378–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs BB, O'Brien E, Khoury JB, Mylonakis E. Methods for using Galleria mellonella as a model host to study fungal pathogenesis. Virulence. 2010;1:475–82. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.12985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junqueira JC. Models hosts for the study of oral candidiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;710:95–105. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5638-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Rodas R, Zaragoza O. Galleria mellonella as non conventional host in research. online video clip youtube, 12 September 2013, web 20 June 2017., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedhila S, Buisson C, Dussurget O, Serror P, Glomski IJ, Liehl P, Lereclus D, Nielsen-LeRoux C. Comparative analysis of the virulence of invertebrate and mammalian pathogenic bacteria in the oral insect infection model Galleria mellonella. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103:24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis JD, Graham JR, Mortensen A. Standard methods for wax moth research. J of Apicult Res. 2013;52:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charrière JD, Imdorf A. Protection of honey combs from wax moth damage. Am Bee J. 1999;139:627–30. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.1.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powning RF, Davidson WJ. Studies on insect bacteriolytic enzymes. I. Lysozyme in haemolymph of Galleria mellonella and Bombyx mori. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1973;45:669–86. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(73)90205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams J. Honey bee pests, predators, and diseases. Ohio, USA; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwadha CA, Ong'amo GO, Ndegwa PN, Raina SK, Fombong AT. The biology and control of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella. Insects. 2017;8. doi: 10.3390/insects8020061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohamed AA, Ansari MJ, AL-Ghamdi A, Mohamed MO, Kaur M. Effect of larval nutrition on the development and mortality of Galleria mellonella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Revista Colombiana de Entomología. 2014;40:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krams I, Kecko S, Kangassalo K, Moore FR, Jankevics E, Inashkina I, Krama T, Lietuvietis V, Meija L, Rantala MJ. Effects of food quality on trade-offs among growth, immunity and survival in the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella. Insect Sci. 2015;22:431–9. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coskun M, Kayis T, Sulanc M, Ozalp P. Effects of different honeycomb and sucrose levels on the development of greater wax moth Galleria mellonella larvae. Int J Agril Biol. 2006;8:855–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mead G, Ratcliffe N, Renwrant L. The separation of insect haemocyte types on percoll gradients; methodology and problems. J Insect Phwiol. 1986;32:167–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brighenti D, Carvalho C, Carvalho G, Brighenti C. Efficiency of Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Berliner, 1915) for control of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Ciênc agrotec. 2005;29:60–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(86)90137-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harding CR, Schroeder GN, Collins JW, Frankel G. Use of Galleria mellonella as a model organism to study Legionella pneumophila infection. J Vis Exp. 2013;22:e50964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metcalfe NB, Monaghan P. Growth versus lifespan: perspectives from evolutionary ecology. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:935–40. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(03)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramarao N, Nielsen-Leroux C, Lereclus D. The insect Galleria mellonella as a powerful infection model to investigate bacterial pathogenesis. J Vis Exp. 2012;11:e4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kavanagh K, Reeves EP. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:101–12. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siva-Jothy MT, Thompson JJW. Short-term nutrient deprivation affects immune function. Physiol. Entomol. 2002;27:206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Champion OL, Wagley S, Titball RW. Galleria mellonella as a model host for microbiological and toxin research. Virulence. 2016;7:840–5. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1203486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banville N, Browne N, Kavanagh K. Effect of nutrient deprivation on the susceptibility of Galleria mellonella larvae to infection. Virulence. 2012;3:497–503. doi: 10.4161/viru.21972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]