Abstract

A key feature of the modified Q-cycle of the cytochrome bc1 and related complexes is a bifurcation of QH2 oxidation involving electron transfer to two different acceptor chains, each coupled to proton release. We have studied the kinetics of proton release in chromatophore vesicles from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, using the pH-sensitive dye neutral red to follow pH changes inside on activation of the photosynthetic chain, focusing on the bifurcated reaction, in which 4H+are released on complete turnover of the Q-cycle (2H+/ubiquinol (QH2) oxidized). We identified different partial processes of the Qo-site reaction, isolated through use of specific inhibitors, and correlated proton release with electron transfer processes by spectrophotometric measurement of cytochromes or electrochromic response. In the presence of myxothiazol or azoxystrobin, the proton release observed reflected oxidation of the Rieske iron-sulfur protein. In the absence of Qo-site inhibitors, the pH change measured represented the convolution of this proton release with release of protons on turnover of the Qo-site, involving formation of the ES-complex and oxidation of the semiquinone intermediate. Turnover also regenerated the reduced iron-sulfur protein, available for further oxidation on a second turnover. Proton release was well-matched with the rate limiting step on oxidation of QH2 on both turnovers. However, a minor lag in proton release found at pH 7 but not at pH 8 might suggest that a process linked to rapid proton release on oxidation of the intermediate semiquinone involves a group with a pK in that range.

Keywords: Q-cycle, bc1 complex, Bifurcated reaction, H+ exit pathways, Kinetic model, Partial processes, Antimycin, Myxothiazol, Azoxystrobin, Stigmatellin

1. Introduction

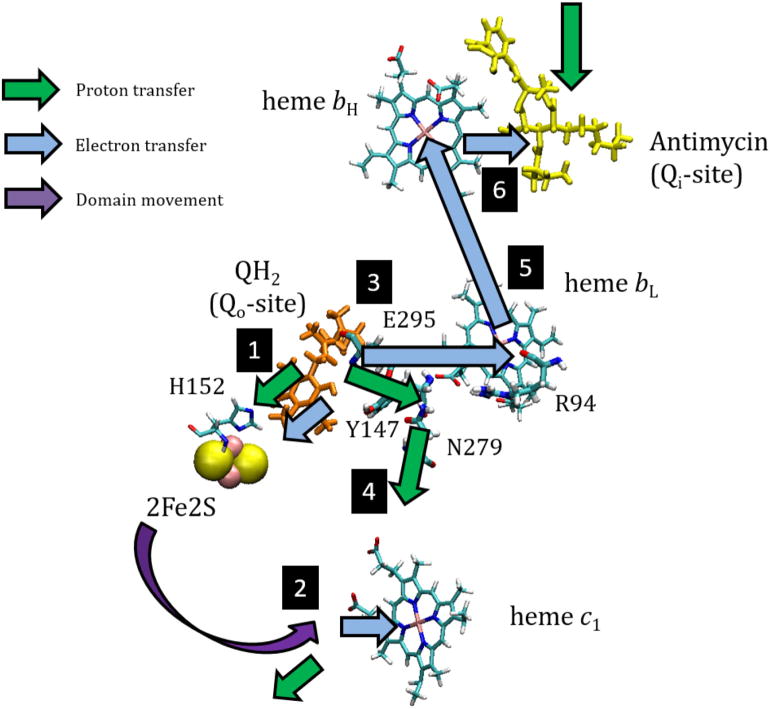

The bc1 complex (complex III of the respiratory chain in mitochondria) oxidizes ubihydroquinone (QH2, quinol) and reduces cytochrome (cyt) c (or c2 in bacteria) and couples the work available to transfer of 2H+/QH2 across the membrane to generate a proton gradient that drives the synthesis of ATP. The Q-cycle mechanism [1–3] by which the complex operates is essentially the same in mitochondria and bacteria, and in photosynthetic or respiratory functions (Fig. 1). The Q-cycle involves a bifurcated reaction at the Qo-site of the complex in which the two electrons from QH2 are passed to different acceptor chains. Partial processes (numbers refer to the scheme) are as follows: 1) in the first electron transfer, QH2 passes an electron and H+ to ISPox to generate SQo (initially in the neutral form, QH•) and ISPH•. 2) The mobile domain of ISPH• rotates in a tethered diffusion to interact with heme c1, transfers its electron to heme c1 and releases its proton to the P-phase (heme c1 is reoxidized by a mobile cyt c2, not shown here). 3) Meanwhile, the semiquinone reduces heme bL and, in 4), the H+ exits to the P-phase. The order of events is still uncertain, but likely QH• dissociates and the H+ exits via a water chain (stabilized by E295, Y147, N279 and R94) and Q•− transfers its electron to heme bL, leaving the quinone (Q) as product. Since SQo is undetectable in normal forward chemistry, the rate constant for its oxidation must be much larger than that for the rate limiting first electron transfer (~103 s−1), as discussed in detail later. 5) The electron transfers from heme bL to heme bH. The intrinsic rate constant is also much higher than the rate limiting step, so no significant transient reduction of heme bL is seen. In the presence of antimycin this would be the terminal acceptor in this chain. In the absence of antimycin, heme bH transfers its electron to the Qi-site where it reduces the quinone to a semiquinone, SQi, taking up a proton from the N-phase (reaction 6). Complete reduction to QH2 requires a second electron, provided by exchange of the Qo-site quinone for a quinol to reform the ES-complex and a repeat of the sequence 1–4, followed by reduction of SQi to quinol by heme bH, with uptake of a second proton from the N-phase. This would return the complex to its original state. The overall result of the cycle is uptake of 2H+ from the N-phase, release of 4H+ to the P-phase, and transfer of 2 e− across the membrane.

Fig. 1.

Q-cycle scheme. A monomer of the bc1 complex is shown with the Qo-site in the ES-complex configuration, and with antimycin bound at the Qi-site (in the uninhibited complex, the Qi-site would be occupied by a quinone). In the ES-complex, QH2 is bound to oxidized ISPox; H152 of the ISP-subunit ligands Fe2 of the 2Fe2S cluster (shown as space-filling spheres), and H-bonds to QH2. Redox centers are highlighted as stick models, with QH2 in orange, antimycin in yellow, and others in CPK colors, and residues in the cyt b-subunit of importance in proton exit (E295, Y147, N279, R94, see text for discussion) are similarly shown.

By recycling the QH2 from the Qi-site to replace one of those oxidized at the Qo-site, the Q-cycle doubles the number of protons pumped. In effect, in the photosynthetic chain, since the overall redox state is restored to that before the flash, this doubles the work stored from each photon.

The overall reaction is given by:

The overall reaction can be partitioned into scalar chemistry and transport, with separate work terms for the two processes:

The subscripts N, P, and S indicate protons transported (taken up from the N-phase (aqueous phase of Negative proton potential), released into the P-phase (Positive proton potential)), or released to the P-phase because of Scalar stoichiometry, respectively. The simple overall reaction Eq. (1) can be dissected into > 20 partial processes. A detailed kinetic model has recently been proposed for the oxidation of QH2 when the turnover is simplified by blocking the Qi-site reaction with antimycin [4,5]. Although truncated, this still encompasses 15 partial processes, with rate constants and equilibrium constants measured directly, or inferred within well-defined constraints.

When grown photosynthetically, the bacterial inner membrane of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, which contains the photosynthetic apparatus, becomes invaginated to maximize the surface area for photon interception. On mechanical disruption, these invaginations break up to form sealed vesicles, the chromatophores [6], which contain a complete apparatus for the light-driven reaction [7]. On activation by a saturating short (~5 μs) flash, kinetics can be followed through absorbance changes, which on the range 530–580 nm are dominated by turnover of components of the photosynthetic chain, including the bc1 complex. The reaction centers generate the substrates for the bc1 complex, and the bc1 complex regenerates the substrates for the reaction center. In chromatophores prepared from wild-type cells grown under moderate light, typical ratios are approximately 2RC:1bc1 complex:1cyt c2, and the stoichiometry of the components leads to a complete cycle in which the bc1 complex returns the system to the initial state in most chains, with the Qo-site of each complex turning over twice to release 4H+ to the internal P-phase as discussed above [2,8]. The ratio is somewhat dependent on growth conditions, and varies in engineered strains, and further complication is introduced by the heterogeneity in distribution of the different proteins arising from stochastic distribution [9]; no matter the mean ratios, the behavior observed would reflect a statistical range of distributions centered around the mean.

In this paper, we measure the kinetics of release of protons associated with the oxidation of QH2 inside the chromatophore vesicles, using neutral red as an indicator [10–14]. Early studies with neutral red in submitochondrial particles identified color changes in the minutes range on activation by addition of ATP, and explored different states of the dye, but these were interpreted mechanistically in the context of binding changes to energized states of the membrane, with chemiosmotic mechanisms dismissed [10,15,16]. Use of pH indicator dyes for measurement of H+ uptake and release has been well-established in photosynthetic systems, where activation of photochemistry by flashes of light can be used to initiate electron transfer without optical artifacts from mixing [17–20]. Studies in chromatophores using indicators partitioning in the aqueous phase had been used to dissect pH changes in the external phase, which provided kinetic data in the μs to ms range consistent with chemiosmotic expectations [18,20–22]. Several unique features of the system in Rhodobacter sphaeroides facilitate investigation of proton release. The chromatophore vesicles are robust, with all showing the same polarity (P-phase inside), and with photo-redox processes tightly coupled to the proton gradient because the membrane is relatively ion-tight. The approach using neutral red was further refined by Junge and colleagues [11,14] to measure proton release in thylakoids, and extended in pioneering work on the chromatophore system by Mulkidjanian and colleagues [13]. We have applied this approach to studies in chromatophores of wild-type Rb. sphaeroides, with a view to more extensive studies of changes on mutagenesis of key residues in the proton exit pathway, currently in progress. Using neutral red, we can isolate partial processes by use of specific inhibitors, and characterize H+ release and electron transfer reactions, and compare them to those of electrogenic processes through the electrochromic response of carotenoids of the light-harvesting complexes [12–14,23–25]. The response to internal pH is isolated by differential buffering of external and internal aqueous phases to localize the response.

2. Methods

2.1. Chromatophore preparation

Experiments were performed using chromatophores prepared essentially as previously described [26], from cells of Rb. sphaeroides BC17 strain (parental strain Ga, but with chromosomal fbc operon excised, and wild-type bc1 complex expressed in a plasmid) grown anaerobically in the light in Sistrom’s medium with 1 μg/mL tetracycline at 30 °C under moderate light conditions. Cells were disrupted by one passage through a French Pressure Cell at 13,000–14,000 lb/sq.in. The sample was centrifuged twice at 27,000g for 30 min to remove unbroken cells and large fragments, then centrifuged at 160,000g for 90 min to separate the chromatophores from the supernatant [26]. Centrifugation was performed at 4 °C, and the sample was kept on ice between steps. The final pellet was resuspended in a pH 7 buffer containing 0.1 M KCl, 50 mM MOPS, and 30% glycerol and stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Spectrophotometric measurement of absorbance changes

Measurements were taken using a single-beam spectrophotometer under computer control, essentially as described in [2], but with hardware and software improved to take advantage of advances in photonics and computational resources. Samples were activated by saturating flashes from a pair of 5 μs xenon lamps orthogonal to the measuring beam. Redox centers were monitored using the following wavelengths: RC, 542 nm, Δεox−red = 10.3mM−1cm−1; cyt ctotal, 551–542 nm, Δεred−ox = 20mM−1cm−1; heme bH, 561–569 nm, Δεred−ox = 19.5mM−1cm−1; heme bL, 566–575 nm, Δεred−ox~13mM−1cm−1, after compensation of contributions from heme bH and reaction center [2,27–29]. Fig. 3A shows traces for the preparation from which the results reported here were obtained, illustrating such data. The electrochromic shift was measured at 503 nm [23,30,31]. Neutral red color changes were measured at 542 nm, close to the absorbance peak of the acidic form, and isolated by subtracting the absorbance change in the absence of dye from the absorbance change in the presence of dye. The stoichiometry of bc1 complex to reaction centers was assayed through absorbance changes at the above wavelengths following activation by a train of 8–10 saturating actinic flashes. Chromatophores were suspended in the medium below, with antimycin present to inhibit the Qi-site reactions, and poised at Eh, pH 7–100 mV, with the quinone pool ~30% reduced, and the high-potential chain initially reduced; in the low potential chain, heme bL was initially fully oxidized, and heme bH 90% oxidized [2,27–29].

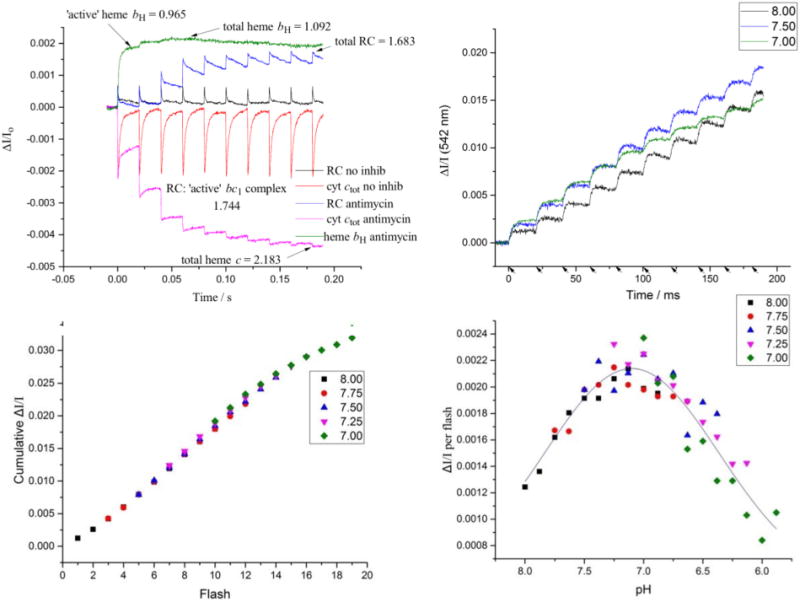

Fig. 3.

Quantification of proton release. A) Kinetic traces for determination of bc1 complex and reaction centers. The traces for RC and cyt ctot in the absence of inhibitor show participation of nearly all complexes in turnover. In the presence of antimycin, the Qi-site is blocked, and turnover of the complex is limited by the low-potential chain, leading to oxidation of the high potential chain (as seen in the cyt ctot and RC traces), and reduction of the low potential chain (as seen in the heme bH trace). Almost 90% of the heme is reduced after the first flash, giving a minimal value for “active” centers. (The values shown obtained by dividing the ΔI/Io values by the extinction coefficient for each center. These scale linearly with concentration over the range shown. The concentration (in μM) is given by multiplying these values by 0.0434, so that [RC] is in the range 0.1 μM. B) Color change after repeated flashes. Chromatophores were subject to repeated flashes and the kinetics of the color change (ΔI/I) after each flash was plotted against time. Traces at representative pH values are shown. C) The cumulative color change (ΔI/I) after each flash was plotted against flash #. The data for pH 7.75 was offset from the origin to align with the pH 8.00 data. This was repeated for pH 7.50–7.00, resulting in a characteristic titration curve. The number of flashes needed to raise the pH by 1 unit was 9 flashes (~0.11 pH units/flash). D) These values were used to convert the data from # of flashes to pH, and the color change per flash (ΔI/I) was plotted against pH. A Gaussian curve was used to fit the data.

Kinetic experiments were performed in buffer containing 0.1 M KCl and a pH buffer. Neutral red experiments used 25 mg/mL BSA as an impermeable buffer, which cannot cross the membrane and thus only buffers the external phase. Electron transfer kinetics were measured in a medium buffered by either 25 mg/mL BSA or 50 mM MOPS. Choice of pH buffer had no discernable effect on absorbance changes of redox centers or bc1 complex function. Temperature was maintained at 30 °C.

2.3. pH and redox poising

All experiments were performed under a flow of argon gas to maintain anaerobic conditions, and were poised at Eh ~100 mV and pH 7, or adjusted −60 mV per pH unit for experiments at different pH. The potential was adjusted using small aliquots of dithionite (to reduce) or potassium ferricyanide (to oxidize) the system. The pH was adjusted using small aliquots of 1 M HCl or NaOH. In preliminary experiments, we found that poising the pH and ambient redox potential simultaneously was extremely difficult in buffer containing only the 1–2 mg/mL BSA used in previous reports [11–14]. With a higher concentration of BSA (25 mg/mL), the pH was sufficiently buffered to allow reliable poising of both potential and pH. We also discovered that this increased the amplitude of neutral red color change, significantly improving our signal-to-noise ratio. Diaminodurene (DAD), N-Ethyl phenazine methosulphate (PES), and N-Methyl phenazine methosulphate (PMS) at 5 μM were added as redox mediators; 200 μM FeEDTA (Ferricethylenediamine tetraacetic) was used as a redox mediator and redox buffer. Except in experiments where the electrochromic shift was measured, 5 μM valinomycin and 0.1 μM nigericin were included. Valinomycin collapses the transmembrane potential, as shown by rapidly decay of the absorbance changes due to electrochromic shifts at 503 nm, so that no membrane potential accumulated, and interference with absorbance changes due to the redox centers was minimized.

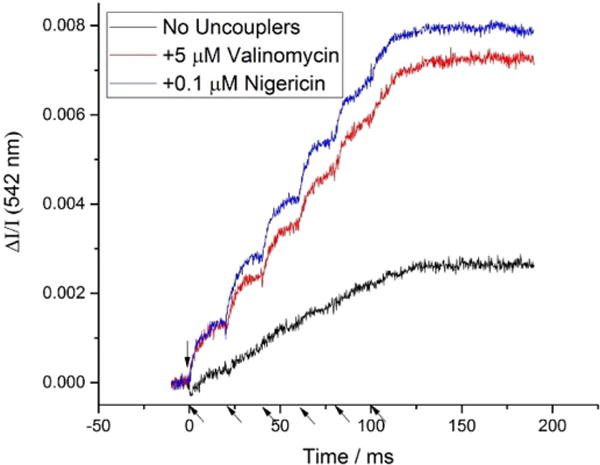

In neutral red experiments, valinomycin greatly enhanced the magnitude of color change (Fig. 2). In the absence of valinomycin, the contribution of membrane potential (Δψ) to the proton gradient from charge transfer across the membrane is initially dominant, because of the low capacitance of the membrane. After a few flashes, backpressure from Δψ inhibits the Q-cycle and slows further proton transfer. In the presence of valinomycin, the membrane potential is collapsed by transfer of K+ down the gradient, releasing the inhibition. The proton gradient then builds up as a pH gradient, requiring translocation of many more protons across the membrane to counter the internal buffering power before backpressure builds up (Fig. 2) [20,25,31,32]. However, the failure to observe the rapid kinetics of proton release in the first turnover in the absence of valinomycin cannot be explained by inhibition from backpressure, because, as seen in Fig. 6A, the full Q-cycle still occurs rapidly, with two turnovers of the Qo-site, in the absence of valinomycin, and must release 4H+ in the process. This lack of inhibition reflects the substantial driving force (Keq > 400, [2,5]), and the level of Δψ after 1 flash (~60 mV), which was not sufficient to inhibit. The anomalous failure to detect the expected proton release in the first flash may reflect an effect of Δψ on the state or distribution of neutral red in the membrane (cf. [15]), or a previously unrecognized sensitivity of proton release to Δψ. From the measurements reported here, the color change of neutral red in the presence of valinomycin clearly represents a loss of absorption by the dissociated form, kinetically linked to the Q-cycle mechanism, and since this was the condition for all experiments measuring proton release, we have deferred further investigation of the anomalous changes in the absence of valinomycin.

Fig. 2.

Effect of valinomycin and nigericin on NR color change. In the absence of ionophores, buildup of a transmembrane potential inhibits proton translocation. The ionophore valinomycin rapidly collapses the potential, allowing proton release that closely matches the kinetics of electron transfer. The pH gradient decays more slowly than Δψ and can lower the yield if flash groups are closely spaced (30 s here). Addition of nigericin at low concentration (0.1 μM) allows relaxation between groups of flashes to overcome that effect, to allow maximal yield. (Flashes indicated by arrows on time axis.)

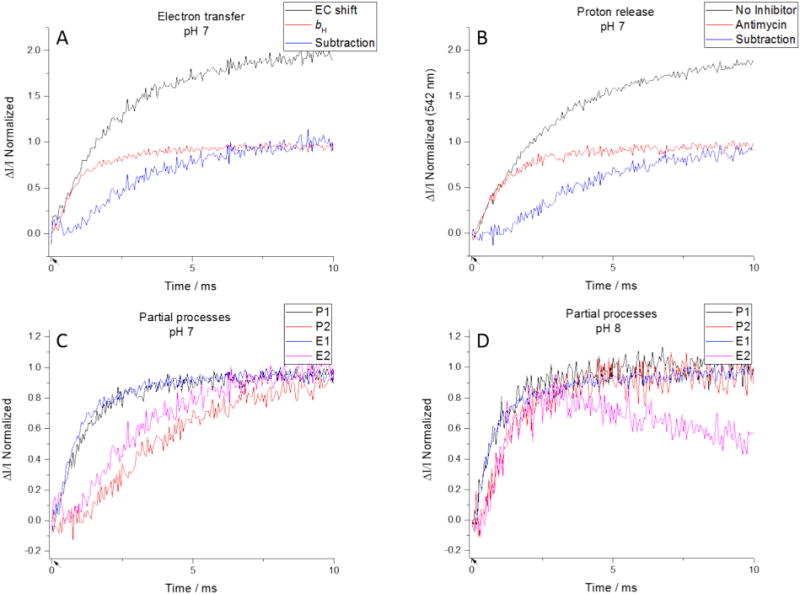

Fig. 6.

Isolation of partial processes. (Top) Kinetics of turnover can be examined using electron transfer (left) or proton release (right). The uninhibited traces (black) represent the kinetics of two turnovers. Antimycin limits the Qo-site to a single turnover (red), so subtracting the latter from the former isolates the electron transfer or proton release from the second turnover. (Bottom) Plotting the proton and electron transfers at a particular pH together, we see a good agreement for the first partial processes, and a pH-dependent agreement for the second partial processes. (Flashes indicated by arrows on time axis.)

Nigericin exchanges K+ for H+ across the membrane; at the low concentration used, it had no discernable effect on pH changes over the timescale (< 50 ms) of kinetics after 1 or 2 flashes. In the absence of nigericin, the full amplitude after a group of 8 flashes was observed only if the time between groups was > 5 min. On addition of nigericin at 0.1 μM to the system could fully relax more rapidly, allowing traces to be averaged with relatively short times (30 s) between groups of flashes (Fig. 2).

We initially used 5 μM oligomycin A to prevent proton leakage through ATP synthase, but we discovered that this had no discernable effect on kinetics taken over the timescale reported. It did, however, increase the time needed for the system to relax to its dark state between measurements, so it was omitted in later experiments (not shown).

2.4. Quantification of pH change

Interpretation of the results depends on knowledge of the stoichiometric ratio of reaction centers to bc1 complex. Fig. 3A shows kinetic data for the preparation used in the analysis of partial reactions below, from which we can directly determine the maximal concentrations of RC and bc1 complex following a group of saturating flashes using the extinction coefficients given above. In this preparation, the kinetics show that the bc1 complex was well-integrated into the photosynthetic chain; in the absence of inhibitors, almost all RC was re-reduced after the first and subsequent flashes, and in the presence of antimycin, a large fraction of heme bH was reduced on the first flash. The ratio of RC:bc1 complex was therefore similar for “active” and total fractions.

Separate experiments (not shown) were performed with a different preparation in which traces similar to those of Fig. 3A showed that the connectivity of the photosynthetic chain was not optimal, with a smaller fraction of “active” chains. Nevertheless, results similar to those in Fig. 3C, D were observed, with the same apparent pK for the neutral red, but with a 3-fold lower yield of protons released per flash.

When chromatophores are subject to a train of flashes in the presence of neutral red, the amplitude of color change varies based on flash number and starting pH (Fig. 3B). The intrinsic proton stoichiometry is independent of pH over the range tested, but the absorbance change of the dye inside the chromatophore in response to a flash will be pH dependent. It will depend on the initial pH inside relative to the pK of neutral red, and on the buffering capacity inside. The latter reflects an ensemble of pK values for proteins, metabolites, lipid head groups, etc., and is expected to be relatively independent of pH over a small range [14]. However, the pK of neutral red is a determinable property, and the amplitude on each flash as a function of pH will follow a simple titration curve, with the ΔA/flash maximal around the pK. Fig. 3B shows the kinetic data for proton release inside at three values of pH included in the set from which points for the curve of Fig. 3C were taken. At pH close to pK, each flash elicits the same color change. At higher pH, the initial flash gives a lower yield, but it increases as the internal pH approaches pK. At lower initial pH, the first flash yield is maximal, but decreases as the internal pH drops further below the pK.

We can use this phenomenon to quantify the ΔpH per flash. We measured the neutral red color change over a series of 8 flashes, with the pH initially set at intermediate values spaced at 0.25 pH units over the range between 7 and 8, and for each plotted the cumulative color change versus flash number (Fig. 3C). Starting with the second-highest pH (pH 7.75), we offset the data from the origin until it aligned with the data from the previous pH (of 8.0), and then repeated the exercise for data sets down to the lowest initial pH (of 7.0). Offsetting by the same number of flashes each time gave the best fit for the data. For a particular chromatophore preparation, the ΔpH per flash appeared to be consistent within each experiment but, as noted above could be significantly different for different chromatophore preparations tested.

The value for ΔpH ~0.11/flash above is in the same range as those found for thylakoids [11,14], and for an earlier estimate based on fluorescence experiments using 9-aminoacridine [33]. For chromatophores, however, Mulkidjanian et al. [13] reported a value for ΔpH of 0.07 for a “weak” flash (activating only ~5% of reaction centers), but ΔpH of 0.8 for a saturating flash. This latter value, which would generate a ΔpH of 6.4 units in 8 flashes, seems absurd in the light of the traces in Fig. 3B, and from previous experience of steady-state measurements. The differential capacity represented by the membrane capacitance (for Δψ), and internal buffering (for ΔpH) can be seen in the large disparity in time course for approach to static head when one or the other provides the major contribution of Δp [20,25,31,32]. We verified that our flashes were saturating (RC oxidation caused by the flash from a single lamp was ~90% of that caused by both lamps firing), so a weakness of activation cannot explain the difference in yield. Both protocols had similar RC:bc1 ratio of ~2:1, so the substrates for bc1 complex turnover generated per flash would be similar in the two experimental systems. Each flash generates two oxidizing equivalents and a single QH2 per 2 RC, on average. The redox potentials at which the experiments were performed were markedly different, 280–300 mV in their experiments, 100 mV in ours. These would result in substantial differences in kinetics and yield but cannot explain the factor of 10 difference in ΔpH/flash. At Eh ~100 mV, the poise of the high potential chain (HPC) and quinone pool were, respectively, initially 100% and 70% reduced, allowing 2 turnovers per flash. Conversely, in their conditions (Eh ~300 mV), the high potential chain and quinone pool were, respectively, ~50% and 100% oxidized, which would allow only ~1 turnover per flash, since only the 1 QH2 generated (in the mean) from RC turnover would be available. We might therefore expect to see twice the ΔpH per flash in our system, not one tenth. Other considerations could be of concern, but we can suggest no obvious set of circumstances, that could account for the large discrepancy, or justify their value, except that their assumptions in deriving a value were not realistic.

2.5. The pKa shift of neutral red in chromatophores

The pKa of neutral red is 6.8 in aqueous solution, but it is known to shift when the dye enters the membrane. The interaction between the positively charged form of the dye and the negatively charged head groups of lipids in the membrane stabilizes the protonated form, shifting the pKa to a more basic value [34]. The data from the preceding experiment could be used to characterize this pKa shift. We calculated the ΔI/I per flash and converted the x-axis from flash # to pH with the assumption of constant stoichiometry of proton release per flash. The data were plotted and then fit with a Gaussian (Fig. 3D); note that the shape of the curve expected is the derivative of the titration curve, with a peak in ΔI/I per flash at the pK. Despite the significant difference in ΔpH/flash for chromatophore preparations mentioned briefly above (Section 2.4), the pKa was 7.1 according to both datasets. This matches the value of ~7.2 found previously in both thylakoids and chromatophores [13,14].

The absorbance changes selected from the difference with and without neutral red are entirely consistent with a response of the dye to pH changes in the chromatophore interior. The changes on flash activation of turnover of the bc1 complex reflect a pKa shifted by binding of the cationic dye to the membrane, and, on flash activation of turnover, changes in concentration of the dissociated form on acidification of the internal volume. By careful use of ionophores, we select conditions so that the proton gradient is determined by the ΔpH component, and eliminate potential artifacts from redistribution of cationic forms in response to Δψ, by rapidly (τ~10 μs) collapsing the membrane potential by K+ flux through valinomycin. When the Qo-site is blocked by stigmatellin binding (see Section 3.2.2), no pH changes inside are observed on flash activation, although the RC turnover and full oxidation of the high potential chain are observed. This is in line with expectations that all events leading to proton release are associated with the bc1 complex, and these are all blocked when the Qo-site reactions are eliminated.

3. Results and discussion

The cyclic electron transfer chain leads to transfer of protons across the chromatophore membrane from outside to in, with a simple overall stoichiometry of 2H+ per QH2 oxidized. However, the set of partial processes contributing is quite complex, and the pattern detected on measurement of pH changes within the chromatophore vesicles requires an understanding of the Q-cycle mechanism (Fig. 1).

3.1. The Q-cycle mechanism

The features of the Q-cycle of importance in forward chemistry emerged from kinetic studies over three decades starting in the mid-1970s, leading to the consensus outlined in the Introduction. At saturating substrate, the bifurcated reaction at the Qo-site determines the rate of QH2 oxidation [4,35–37]. The reaction proceeds from an ES-complex in which the oxidized Rieske iron sulfur protein (ISPox) is held in tight association with the second substrate, QH2, through a H-bond between His-152 (H152) of ISP and the quinol –OH [38–44]. On oxidation of QH2 by ISPox, the rate expected from the distance dependence formalized in the Moser-Dutton approach [45,46] (~7 Å) was in the range 108 s−1, but the observed rate was only ~103 s−1 [37]. Why so slow?

The paradox could be resolve through an understanding of the pH dependence of the rate of QH2 oxidation. When [QH2] is saturating, the ES-complex is fully populated only when the second substrate is also saturating. This depends on pH, with an observed pK at ~6.5. We have demonstrated that this value reflects dissociation of H152 [37,41]. The value is displaced from the value seen in the isolated protein (pKox1 ~7.6, [47–49]) by the work involved in formation of the H-bond with QH2. From the pK values of QH2 (pK ~11.5, [50]) and H152, the former must be the H-donor. The limiting step is a proton-coupled electron transfer, with the electron and H+ from QH2 both transferred through this H-bond to ISPox, with reduction of the 2Fe2S cluster and pronation of H152. The electron can transfer only when the H+ is positioned along the H-bond close to Nε of H152 (the acceptor configuration), with a probability of 10−5 that depends on the pK difference between H152 and QH2 (a Brønsted term). Then, the observed rate can be economically explained if the expected rate (of 108 s−1) is lowered by this factor [35,51,52]. However, other factors complicate the picture; notably, the reaction is strongly endergonic, so the reaction is observed to proceed only if the products are rapidly removed. The reaction is neutral, generating semiquinone (SQo) at the Qo-site, initially as QH• in complex with ISPH• [53]. Further progress of the forward chemistry brings the bifurcation of electron transfer into play. Removal of SQo occurs through its oxidation by heme bL, but this involves several steps. The initial intermediate complex (QH•·ISPH•) rapidly dissociates, and the extrinsic domain of ISPH• rotates away to transfer the electron to ferriheme c1 of the cyt c1 subunit (releasing the proton to the P-phase), and from there to the oxidized reaction center via cyt c2. The intermediate complex is formed in the domain of the Qo-site at which the ES-complex was formed, distal from heme bL. After dissociation, oxidation of QH• requires removal of both H+ and electron. Simple kinetic considerations suggest that the rate of the second electron transfer must out-compete the back reaction for the first electron transfer, with the ratio of rate constants determined by the degree of endoergicity, and such considerations provide severe constraints on possible mechanisms [35,37,51]. Kinetic modelling [5] shows that, to keep [SQo] as low as possible, electron transfer in the range > 107 s−1 is needed to account for the experimental data. This would be possible only if the distance for electron transfer was decreased, requiring movement of SQ in the Qo-site from the distal domain in which it is formed to a position closer heme bL [38,39,43].

These partial processes in the second step, - dissociation of the intermediate complex, dissociation of QH• to release the H+, movement of the Q•−, and transfer of the electron, - must all occur on the > 107 s−1 s time-scale, - much faster than the rate limiting step. Although rates measured are constrained by the limiting step, it will be obvious from the above that measurement of the kinetics of proton release could provide useful constraints on plausible mechanisms, especially in strains mutated so as to shift the limit to some process in this second step.

3.2. Partial processes associated with H+ release

When the Q-cycle is initiated by addition of QH2 to the fully oxidized complex, the two paths for proton release from the Qo-site are correlated with electron transfers in the separate acceptor chains for electron bifurcation. After formation of the ES-complex, the first proton and electron from QH2 transfer together to reduce the ISPox to ISPH• in the HPC, leaving an intermediate product complex, QH•·ISPH•, which rapidly dissociates to QH• and ISPH•. The first proton is them released when the ISPH• reduces ferricyt c1. The second electron is transferred from QH• to heme bL in the low potential chain (LPC), and then to heme bH. The H+ from QH• is likely released as the intermediate complex dissociates. We have postulated that exit from the Qo-site is by transfer via dissociable groups to a water chain [43,54], which is stabilized in part by one of the propionates of heme bL [53,55].

This simple scheme is complicated by two factors:

In the experiments reported here, the system starts in an equilibrium state, poised with the Q-pool ~70% oxidized and the high potential chain reduced, in which the Qo-site is occupied in ~70% of centers by an EP-complex (see below). However, the bifurcated reaction proceeds from the ES-complex formed at the same position as a metastable state resulting from oxidation of ISPH• to ISPox after flash activation. There is therefore a change of state resulting from this transition which involves protolytic processes.

Formation of the ES-complex depends on pH through the pKox1 of ISPox, so the first electron transfer and the proton release observed is also pH dependent.

The partial processes involved can be defined more formally by reaction equations.

With RC:bc1 stoichiometry of ~2, typical in our chromatophores, flash excitation (↯) generates 1QH2 for each bc1 complex monomer, and two oxidizing equivalents, initially used to oxidize cyt c2.

| (1) |

At pH 7 and 100 mV, the quinone pool is 30% reduced, the LPC initially oxidized, and the HPC initially reduced. In most bc1 complexes (~70%) the Qo-site is occupied by Q.ISPH•, an enzyme product (EP−) complex, detected through the gx = 1.80 line of the EPR spectrum of ISPH• [35,38]. With Em,7 ~300 mV, and pK ~12.5, ISPH• is always protonated in the neutral range. On flash activation, oxidation of the HPC by ferricyt c2 releases the proton from ISPH• to yield ISPox, which, after Q is exchanged from the site, allows formation of the ES-complex with QH2 and initiation of the forward chemistry. The stoichiometry of proton release in this step depends on pH and the pK of ISPox; a fraction of the released H+ will rebind to ISPox, depending on these parameters.

| (2a) |

In formation of the ES-complex, only the dissociated form of ISPox is bound. In effect formation of the complex pulls this form out of the equilibrium mix (in square brackets, Eq. (2b)), and the equilibrium poise over to release the H+ from ISPox(H+).

| (2b) |

As a result, the measured pK value is displaced from that for pKox1 (~7.6) in the isolated protein to pKapp ~6.5, with the free-energy difference formally equal to that provided in the binding reaction [35]. Consequently, at pH > 7, in most centers, the oxidation of ISPH• yields a H+ (Eq. (2a)).

Quinol oxidation proceeds from the ES-complex, and begins with a hydrogen transfer to the ISP, regenerating the initial ISPH•. This is initially in an intermediate complex, QH•·ISPH•, which rapidly dissociates [53] (Eq. (3)). Since the QH• is now available for oxidation by the LPC, we now have to include that in our equation:

| (3) |

Likely the second proton is released at this point (Eq. (4)) and passed to the water chain. As this occurs, the electron from Q•− is transferred to heme bL, then to heme bH, then to the Qi-site where it reduces a quinone (as shown here) or semiquinone (depending on the state of the Qi-site reaction), taking up a proton from the N-phase.

| (4) |

| (5) |

If no oxidizing equivalents are available, this returns the Qo-site to its initial equilibrium poise; Q can equilibrate with the pool (~70% oxidized), and can also complex with ISPH• to form the EP-complex.

If oxidizing equivalents are still available in the HPC, oxidation of ISPH• by cyt c1 can occur again, releasing a proton and (after exchange of Q for QH2) reforming an ES-complex. The second turnover then proceeds through the same sequence as above, with the second electron transferred across the membrane fully reducing the Qi-site occupant (taking up another proton from the N-phase) and returning the complex to the initial state (Eqs. (6), (7))

| (6) |

| (7) |

Except for the HP+ generated on oxidation of the ISPH• present initially (which is released with t1/2 ~150 μs), release of all other H+ to the P-phase will reflect the rate-limiting first electron transfer, convoluted with turnover. Since the second turnover follows the first without any hiatus, exit of product Q, and replacement by QH2 (Eq. (6)) must also be rapid compared to the limiting step.

3.2.1. The stoichiometry of H+ release

Different inhibitors will halt the overall process at different points, so by comparing proton release between different inhibition states we can isolate the partial processes associated with proton release. The overall H+ release will depend on the RC:bc1-complex ratio, and can be understood in turns of the apparent pK of neutral red, and the assumption that release of protons from complete oxidation of QH2 follows the expectation of the reaction equation. Since the Q-pool is in > 50-fold molar excess of the complex, when starting with a 30% reduced Q-pool at any pH, QH2 is in excess, and turnover of the uninhibited bc1 complex will consume the oxidizing equivalents generated by photoactivation of RC, to return the system to the initial state if the dark interval between flashes is long enough. For example, with a stoichiometric ratio close to the “ideal” 2:1, the expected value is 4H+ released for complete turnover, and we could simply normalize the H+ release in the presence of inhibitors to this value. However, even if we had a perfect model, we would not expect total agreement between prediction and data because of variability introduced by heterogeneity in chromatophores. Each chromatophore is different, because of heterogeneity in volume, and in the relative concentrations of the proteins because of their stochastic distribution [9]. The work presented here is based on a single preparation, with RC:bc1 complex of ~1.75 in active chains, close to the “ideal” of 2. Since simplicity aids comprehension, we have chosen to treat the system as if the proton yield was 4H+/bc1 complex on complete turnover, as expected from the ideal ratio of 2, on the understanding that uncertainties above preclude precision. With this caveat in mind, we will note in discussion departures of experimental outcome from this ideal that can be attributed to the non-ideal ratio.

3.2.2. Lack of H+ release in the presence of stigmatellin

The simplest case to interpret is the behavior in the presence of stigmatellin. Stigmatellin, and similar class I inhibitors, bind in the volume of the Qo-site distal from heme bL, in a complex with ISPH• which excludes occupancy of weaker binding quinone species. This precludes formation of the ES- or EP-complexes, or any turnover at the Qo-site. The inhibitor is so tightly bound that cyt c1 is unable to oxidize it; binding raises the Em, 7 for ISPH• to > 500 mV, but even when the poise of the HPC is raised above this value by multiple flashes, no oxidation of ISPH• is seen. From this, no release of protons would be expected either from ISPH• oxidation, ES-complex formation, or from turnover. Our data match these predictions, with negligible indicator change (equivalent to ~0.1 protons) on flash-activation over the pH range 6.5–8.5 (Fig. 4A). The result also confirms that no pH change associated with the donor reactions to P+ occurs. Furthermore, in addition to showing that all proton release is associated with the bc1 complex reactions, these traces also provide controls for responses of neutral red not associated with its pH indicator function. None of the effects that might be expected from “energized” membrane binding [10,15,16] in response to the transient Δψ generated by RC turnover (before it decays through K+ exit via valinomycin) are seen, indicating that if they occur, they are so slow as to be insignificant on the timescale of these experiments.

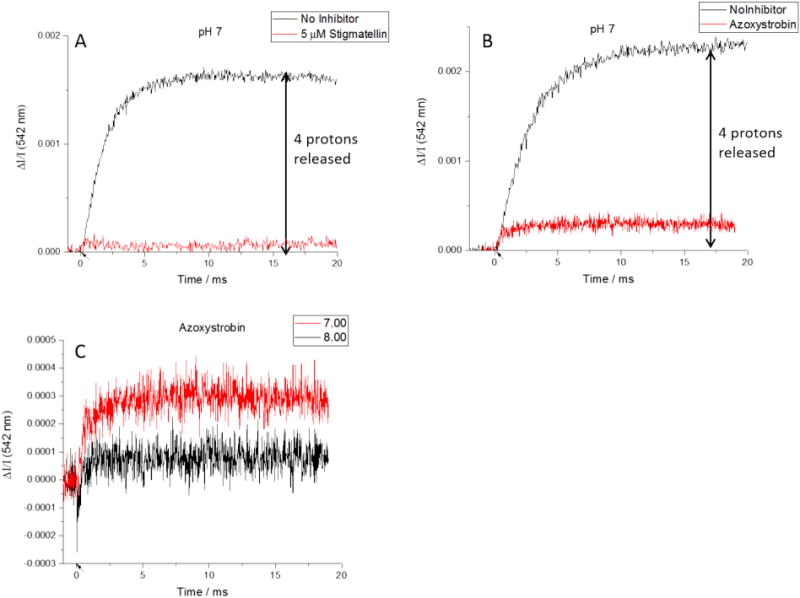

Fig. 4.

Color change in the presence of Qo-site inhibitors. A) Stigmatellin blocks all proton release by tightly binding ISPH and preventing its oxidation. B) Azoxystrobin also prevents Qo-site turnover, but proton release from oxidation of ISPH still occurs. C) Although net proton release is always observed in the presence of azoxystrobin, at higher pH values there is also an unexpected initial uptake of protons. (Flashes indicated by arrows on time axis.)

3.2.3. Proton release in the presence of myxothiazol or asoxystrobin

Inhibitors of Qo-site in a second class, typified by myxothiazol and MOA-type inhibitors like azoxystrobin (class II inhibitors), bind tightly in the volume of the site proximal to heme bL, and displace more weakly binding quinone species. This leaves the ISP mobile domain unconstrained by binding, and free to interact with cyt c1. When ISP is initially reduced, a proton will be released on oxidation of ISPH•, but because the inhibitor prevents binding of Q or QH2, no proton exchange on formation of the ES-complex, or from QH2 oxidation is expected.

| (8) |

On flash excitation in the presence of azoxystrobin at pH 7 and 7.25 a rapid proton release is observed (Fig. 4B). The proton release expected would depend on the pKa of ISPox. With any pK in this range, the trend we expect is a decrease in the ISPox(H+) fraction (and an increase in proton release) over the pH range from pH 6 to 8.5. At the pKa, half the protons released from ISPH• would be taken up again, on formation of ISPox(H+), and the net release would be 0.5. However, it is uncertain what value for pKa is appropriate under these conditions. In the isolated ISP subunit, the pK is that from pKox1 of ISPox at ~7.6, attributed to H152. As noted above (see Eqs. (2a), (2b)), in the uninhibited bc1 complex, with the quinone pool partly reduced, on formation of the ES-complex with ISPox, the pKa is shifted to ~6.5 due to stabilization of the deprotonated form of ISPox on binding with QH2 [35]. With the Qo-site occupied by azoxystrobin, the ES-complex cannot form, so this displacement of pK would not occur.

In light of the above discussion, the amplitude of the proton release at pH 7 (0.53) is higher than expected if the pKox1 value pertained. However, there may be other interactions between the ISP and the cyt b- or c1-subunits, displacing the pK value from that seen in the isolated ISP. A simple interpretation would be that the ISP under these conditions has a pKox1 in situ different from that in the isolated protein by ~−0.4 units. Although Ugulava et al. [56] determined a titration curve in situ, the slope of the pH dependence in this range was not well enough defined to establish a difference from the pKo×1 of the isolated subunit.

Two other effects complicate interpretation, and preclude detailed analysis of effects over a wider range. The first is the distribution of electrons in the partially reduced HPC. The midpoint potential of the ISP is pH-dependent (decreasing from 300 to 280 over the pH range 7–8), and the midpoint potential for cyt c1 at 270 mV is pH independent. Accordingly, the number of protons bound to the ISP depends on the pH dependent equilibrium among three states:

| (9) |

Consequently, the equilibrium constant for oxidation of the ISPH• by cyt c1 varies from ~0.32 to ~0.67 over the pH range tested.

The second factor is an unexpected absorbance change, observed only when neutral red is present and therefore seen in the difference measured. At pH 7.5 and above there is still net proton release, but we also see a rapid negative color change, indicating uptake of protons from the chromatophore interior (Fig. 4C). The amplitude of this rapid change increases with pH, showing a pK ~7.7. Interpretation of the slower phases depends on the properties attributed to this new rapid component. The kinetics of the color change are faster than any electron transfer event outside the photochemical reactions, so it would be readily detected under other conditions. We see no evidence that it occurs on flash-activation in the presence of stigmatellin, or antimycin, or in the uninhibited complex. We therefore conclude that the uptake occurs only in the presence of azoxystrobin (or myxothiazol), and we are confident that the rapid component does not complicate analysis in the absence of class II inhibitors. That being said, we have no adequate explanation for the effect, and will defer further discussion, but note that it precludes detailed analysis in terms of the equilibria of Eq. (9).

3.2.4. Proton release in the presence of the Qi-site inhibitor antimycin

Antimycin displaces all quinone species from the Qi-site, preventing oxidation of heme bH. With heme bH initially oxidized, turnover proceeds as in the uninhibited complex through the first quinol oxidation and reformation of the ES-complex, except for the fact that heme bH remains reduced. After the first electron transfer (Eq. (5)), the second step is described by:

| (10a) |

| (10b) |

It might be expected that, since there is still an oxidizing equivalent in both the LPC the HPC chain, a second turnover would occur. However, further turnover is limited by the change in driving force available. Both chains receive an electron from QH2, which reduces the most oxidizing center. In the HPC, the higher potential center is ISPox, while in the LPC the higher potential center is heme bH, both reduced in the first turnover. This leaves mostly heme c1 (in the equilibrium mix of Eq. (9)) and heme bL, respectively, as acceptors in the second turnover. Consequently, the Keq for oxidation of the second QH2 is much smaller (~3 vs. ~400), mainly because of the difference in Em values (Em,7–40 mV for heme bH, Em,7 ~ − 90 mV for heme bL), and turnover is restricted to oxidation of ~1 QH2. Prediction of proton release in the presence of the Qi-site inhibitor antimycin is complicated by this restriction. Without additional oxidizing equivalents from further flashes to drive the reaction forward, ≤15% of sites are expected to turn over a second time. Overall, turnover of the Qo-site would be expected to release ≤2.3 protons from oxidation of QH2 if the RC:bc1 ratio of 2 pertained.

The stoichiometry of protons released is also complicated by factors related to the pKa of ISPox(H+) already discussed in Section 3.2.3. In the context of the equilibria of Eq. (9), as pH increases, the equilibrium in the HPC shifts to favor ISPox (right two terms), and the equilibrium for ISPox shifts towards the deprotonated form. Both of these trends will reduce the number of protons retained by ISP, thus increasing the proton release we might expect to observe (Fig. 5C).

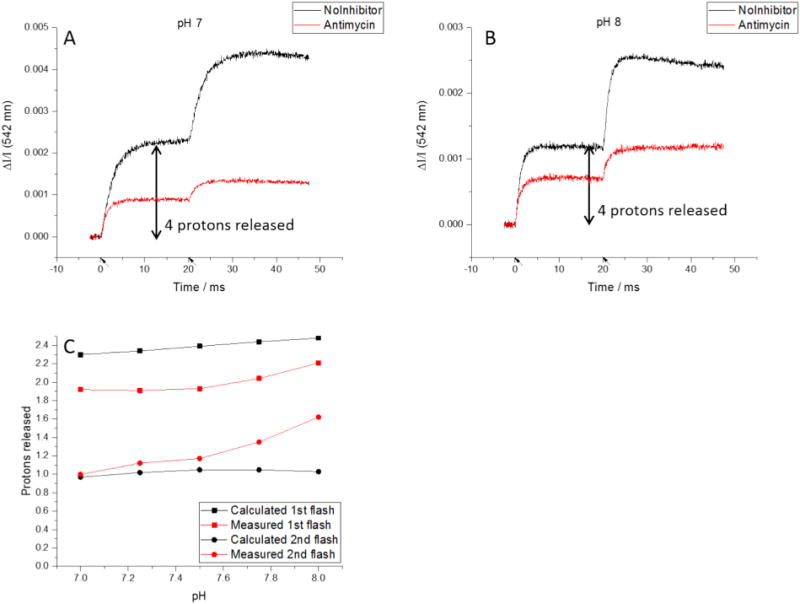

Fig. 5.

Proton release in the presence of antimycin. A, B) A pH-dependence was observed for release of protons after both the first and second flashes. (Flashes indicated by arrows on time axis.) C) The measured proton release was less than the calculated value for the first flash but greater for the second flash. The pH-dependence was more pronounced than expected for both flashes.

At the “ideal” stoichiometry of 2 RC:bc1 complex, the first flash generates two oxidizing equivalents per bc1 monomer, consumed in the first turnover. Introduction of two additional oxidizing equivalents by a second flash will drive the reaction to allow additional turnover, delivering additional electrons and protons to each chain. Exit of the H+ released in the second electron transfer will depend on the pK values among dissociable groups in the proton exit path. Since heme bL shows a pH-dependent redox potential [57], reduction leads to binding of a proton, so we might expect that the proton released on oxidation of QH • would remain bound if any of the pK values (for QH•, E295, or heme propionates) was higher than the pH of the N-phase. However, the operational pK values are not known. Although the equilibria above will pertain (Eq. (9)), the proton release from the HPC after the second flash should be largely pH-independent, because the effects mostly cancel out (Fig. 5C).

The data show that the proton release in the presence of antimycin has a pH-dependence after both the first and second flashes (Fig. 5). Although we predicted proton release after the first flash would increase as the initial pH increased, the calculated value consistently overestimates the number of protons released and underestimates the magnitude of the pH-dependence. These discrepancies likely reflect, at least in part, the difference in RC:bc1 complex between the “ideal” value of 2 assumed in the predicted values, and the measured value of 1.744 (Fig. 3).

We should perhaps consider an alternatively perspective, that overestimation of proton release after the first flash might reflect a mistaken assumption that the proton is released to the water chain immediately. It could be retained by longer-range electrostatic effects. For example, although Em,7 for heme bL is normally around −90 mV, in mutant strains lacking heme bH (from mutation of an axial histidine ligand) the Em,7 of heme bL is shifted to around −10 mV [58]; the Em,7 normally seen likely reflects a displacement (ΔEm,7 ~ − 80 mV) induced by the coulombic field of ferroheme bH. Any coulombic field would be felt by other charged states and could therefore be reflected in pK values. In the uninhibited complex, any coulombic effects would be transient, because, although the Qi-site semiquinone (SQi) is anionic, it is formed only transiently, and the charge would be compensated by binding of a proton from the N-phase at a neighboring site. In the presence of antimycin, ferroheme bH accumulates after the first flash. If antimycin binds in such a way as to prevent proton uptake, the charge on heme bH could exert a coulombic effect, which might inhibit escape of the proton down the water chain from the Qo-site.

For the second flash in the presence of antimycin, ferroheme bL accumulates. While the observed proton release matches the predicted value at pH 7, we see an unexpected pH-dependence similar to that after the first flash. As noted above, the release of the second H+ will reflect pK values of groups impinging on the water chain. At present, we have no direct information on these values. However, we note that heme bL shows a pH dependent Em, suggesting that a H+ is bound on reduction, and it seems quite likely that this reflects a change in pK of one of the propionates. In the first turnover, the heme is reoxidized so rapidly that no significant transient reduction is seen; however, after the second turnover, the heme remains reduced, and, depending on pK, the propionate could provide a H+ trap, restricting release to the water.

3.3. Isolation of the kinetics of partial processes

A single flash in the absence of inhibitors results in two turnovers of the bc1 complex, which follow a continuous trajectory, returning the complex to its initial state. It is therefore not possible to distinguish the separate partial processes through direct observation of one reaction component. However, the reaction generates a proton gradient, so we can measure the full turnover from the kinetics of proton release, or, in the absence of valinomycin, from the kinetics of the transfer of charge across the membrane detected in the electrochromic change of carotenoids [23–25]. Furthermore, through use of inhibitors we can separate RC changes from those of the bc1 complex, and we can also separate the kinetics of the first and second turnovers for both proton release and electron transfer in the bc1 complex.

The first turnover of the Qo-site can be measured directly by observing the reduction of heme bH in the presence of antimycin (Fig. 6A, red trace), because the intervening reactions are all rapid compared to the rate limiting step. To determine the second turnover we can take advantage of the electrochromic absorbance change of carotenoids (measured at 503 nm) in response to a change in Δψ to measure the kinetics of electrogenic processes [25]. In the full turnover of the photosynthetic chain in chromatophores, electrons cross the membrane through the photochemical reaction center (to generate a rapid phase in the kinetics), and through the bc1 complex (a slower phase) [31,59]. Myxothiazol (or azoxystrobin) and antimycin are specific to the bc1 complex, so subtracting the absorbance change in the presence of inhibitors from that without inhibitors, we can determine the kinetics of electrons crossing the membrane in the Q-cycle (the slow phase). The latter generates a significant fraction (ideally 50%) of the voltage difference developed in response to a flash (Fig. 6A, black trace). We can take advantage of the fact that the initial rate of the electrochromic response closely matches the electron transfer rate measured through reduction of heme bH, to normalize traces to take account of the fact that the electron crosses only half the dielectric when antimycin blocks its oxidation [60]. Then subtraction of the normalized heme bH reduction kinetics (or the slow phase in the presence of antimycin) from the electrochromic change in its absence reveals the kinetics of the second turnover of the Qo-site (Fig. 6A, blue trace) [2,60].

The method for separating the proton release of the first and second turnovers is similar but requires no normalization. Since the external phase is highly buffered, we see only the proton changes inside the chromatophores, all from the bc1 complex. We expect the proton release in the presence of antimycin to be predominantly from a single turnover of the Qo-site. Comparing the uninhibited and antimycin-inhibited traces (Fig. 6B, black and red traces, respectively), we see a very close match between both the rate and timing of the initial neutral red color change, suggesting that the antimycin-insensitive proton release is the same as the proton release from the first turnover in the absence of inhibitors. By subtracting the antimycin trace (proton release from first turnover) from the uninhibited trace (proton release from two complete turnovers) we isolate the kinetics of proton release from the second turnover (Fig. 6B, blue trace).

To simplify discussion of these partial processes, we will refer to them as E1, E2, P1, and P2, which denote the electrogenic events (E) or proton release (P) associated with the first (E1, P1) or second (E2, P2) turnover (Fig. 6C, D). Note that for each QH2 oxidized, we expect 2H+ to be transported (eq. 1), detected either through electrogenic events, or release of protons. However, the net oxidation of 1 QH2 in the uninhibited complex involves two turnovers of the Qo-site, in each of which 1 QH2 is oxidized. Then, E1 and E2 each represent a single event (an electron passing across the membrane through the LPC, associated with turnovers 1 and 2), but P1 and P2 are more complicated. First, two protons are released inside on oxidation of each QH2, one of which is scalar and the other of which is transported. The scalar proton is, in effect, that associated with reduction and oxidation of ISP. The transported H+ is, in effect, that released on oxidation of SQo, which is stoichiometric with the electron passing through the LPC. P1 and P2 refer to all of the protons released by the first and second turnovers, respectively. Second, protons released in the presence of antimycin (P1) include those released on oxidation of ISPH• prior to Qo-site turnover (see Section 3.2.3), and those released on oxidation of 1 QH2. This simple case is complicated by the small number of complexes which undergo a second turnover, and the protons passed to the HPC during the first turnover that are retained by ISPH. We must also consider the possibility that, in the presence of antimycin, the protons released on oxidation of SQo are, depending on the pK values of dissociable groups, trapped rather than released to the water chain (see Section 3.2.4). Despite these complications, we find an obvious similarity between the kinetics of the two turnovers when measured either through electron transfer or proton release. There is an excellent match between the kinetics of E1 and P1, and an interesting relationship between P2 and E2 that is pH-dependent.

For electron transfer, there is a pH-independent initial delay of ~150 μs after the flash. This is the time expected for the oxidizing equivalents from the reaction center to reach ISPH•, involving diffusion of oxidized c2 from the RC to the bc1 complex, and oxidation of heme c1. A similar delay is also expected for proton release, because the dominant contribution is from oxidation of heme c1, which precedes both events; the electron transfer from ISPH• itself is rapid [60–62]. Neutral red appears to respond rapidly to proton release, as there is no discernable delay between initial proton release and initial electron transfer observed. The kinetics of electrochromic change in the absence of inhibitors are monotonic, showing that all processes, including exchange of Q and QH2, are rapid compared to the limiting first electron transfer.

The lag before the second turnover simple reflects the sequential course of events, complicated by a normal distribution of rates for individual events about the mean represented by the formal rate constant. This makes it difficult to quantify the “ramp-up” period before the process reaches its maximum rate. However, there is still good agreement between P2 and E2. The pH-sensitivity of both first and second turnovers reflects the pH dependence of Qo-site turnover [47].

While the initial rate of E1 and P1 are in good agreement, proton release is significantly slower than electron transfer for the second turnover at pH 7. As pH increases, the rates for all 4 processes increase, with the most significant increase for P2. Significantly slower than E2 at pH 7, it has the same rate by pH 8. It is possible that this is related to the pH dependence for protons released in the presence of antimycin (Fig. 5).

The relations we observe between electrochromic shift, heme bH reduction, and total proton release differ significantly from those found by Mulkidjanian and Junge [11]. Most striking is the discrepancy between the electrochromic shift and bH reduction in their results. Experiments performed in our lab over several decades have found a close kinetic match between those two processes, so we find their result surprising and inexplicable. In the presence of valinomycin to collapse Δψ, our results show good correlation of electron and proton transfer. Only in the absence of valinomycin do we see any lack of correlation, but that clearly reflects a response of the indicator unrelated to pH change. However, although we do not fully understand this effect, it is observed only when a significant transmembrane potential persists over the time of measurement. From the close match to electron transfer and to expectation from the kinetic model, our results show that the color change of neutral red observed in the presence of valinomycin provides an accurate measure of the rate at which protons are released to the internal aqueous phase.

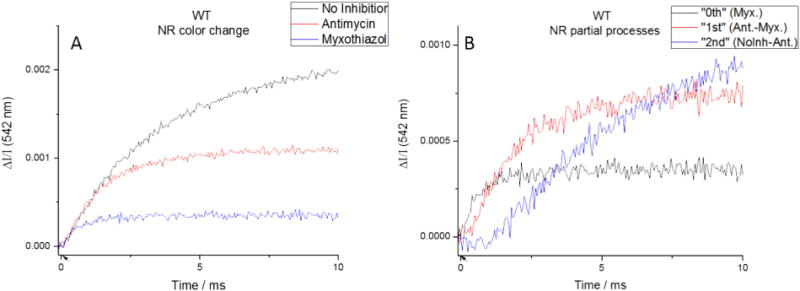

3.3.1. Separation of the proton release from ISPH• oxidation and from turnover

Our initial expectation was that 3 phases of proton release would be readily distinguished: the initial release on oxidation of ISPH• (which we refer to as the “0th” turnover); proton release from oxidation of SQo generated in the 1st turnover (on oxidation of the first QH2); and proton release from the 2nd turnover. All three processes occur in the absence of inhibitors, antimycin prevents the 2nd turnover, and azoxystrobin prevents both the 1st and 2nd turnovers. The three phases could be isolated by simple subtractions: azoxystrobin (0th turnover); antimycin minus azoxystrobin (1st turnover); no inhibitor minus antimycin (2nd turnover). However, the pH titration done in the presence of azoxystrobin presented a problem. At higher pH, there was a rapid uptake of protons that did not occur in the other inhibition states (see Section 3.2.3). Since the azoxystrobin data included this additional phase, it could not be used to subtract out the 0th turnover from the other datasets.

In refining our model to account for these discrepancies, it became obvious that quantification of proton release was complicated by the different values for pKa of ISPox(H+). In the presence of asoxystrobin or myxothiazol, formation of the ES-complex between ISPox and QH2 does not occur. Consequently, the change in apparent pKa associated with binding, and the related release of H+ from ISPox(H+) on selective binding of the dissociated ISPox do not occur. As a result, neither the amplitude nor the kinetics of this phase in the presence of asoxystrobin match those in its absence. In addition, in the absence of inhibitors, a substantial fraction (~70%) of ISPH• is initially bound with Q in the “gx = 1.80” complex (see Eq. (2)) [42], and becomes available to heme c1 only after dissociation and movement of the extrinsic mobile domain. This adds a small addition delay to that before oxidizing equivalents reach the HPC. Consequently, the kinetics of proton release from ISPH• oxidation (τ ~150 μs) are convoluted with the release on formation of the ES-complex, and from QH• oxidation in the ensuing forward chemistry (τ > 400 μs). Despite these complications, when results from the three states (no inhibitor, antimycin, antimycin + azoxystrobin) are plotted on the same axes, there is good agreement in initial rate (Fig. 7A). Subtracting to isolate the partial processes also yield reasonable results. Subtraction of the change in the presence of myxothiazol (black trace) from that in the presence of antimycin (red trace in A) reveals a flat lag in the difference (red trace in B), showing that the initial kinetics are the same, and suggesting that this fraction reflects the same process, – oxidation of ISPH•. The remaining kinetics reflect processes determined by formation of the ES-complex, and the onward forward chemistry of the first turnover. Subtraction of the kinetics in the presence of antimycin from uninhibited kinetics (red and black traces, respectively, in A) shows as in Fig. 5, the kinetics of the second turnover.

Fig. 7.

Isolation of initial proton release. (Left) Matching initial rates suggests that the same initial process is taking place in each inhibition state. (Right) Subtracted traces appear to show that there the three processes (initial proton release, 1st turnover, 2nd turnover) separable by this technique. (Flashes indicated by arrows on time axis.)

4. Conclusions

We have refined protocols for application of neutral red as in indicator of pH changes inside chromatophores, and demonstrated that under appropriate conditions, proton release inside can be quantitatively assayed. We examined the electron and proton transfer associated with turnover of the bc1 complex, measuring the kinetics of both proton release and electron transfer for specific partial processes associated with turnover of the Qo-site. Despite the uncertainties in observed stoichiometry, the overall pattern of proton release follows remarkably well the expectations from an earlier kinetic model [5], with partial steps represented by Eqs. (1)–(10b), and on that basis we can claim to have identified the processes involved. For the proton released on oxidation of ISPH• in the HPC, the main features are clear, but for that in the LPC, many atomistic details are still unknown. We used inhibitors to block turnover at different points during the full enzyme cycle (two turnovers of the Qo-site, triggered by a single flash). Stigmatellin blocked all proton release, antimycin limited the Qo-site to a single turnover, and antimycin plus myxothiazol allowed only an initial, turnover-independent proton release from ISPH• oxidation. Comparison between inhibition states allowed us to isolate partial processes. Titrating over the pH range 7–8, we found a weak pH-dependence of kinetics of proton release when compared to those of electron transfer on oxidation of SQo. At pH 7, for the 1st turnover, proton release and electron transfer were closely matched, but proton release was significantly slower than electron transfer for the 2nd turnover. At pH 8, there was no discernable difference between the kinetics of electron transfer and proton release. A possible explanation for this is that there is a residue with a pKa in that range which needs to be deprotonated to facilitate proton release.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support from the Department of Biochemistry for research supplies and teaching stipend for C.A.W. Early phases of the research were supported by a grant from the National Institutes for Health, NIGMS GM035438 to A.R.C. Computational resources were provided through an XSEDE start-up grant MCB150083 and XSEDE Research Request MCB160130 to A.R.C.

Footnotes

Transparency document

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- 1.Crofts AR. The Q-cycle, - a personal perspective. Photosynth Res. 2004;80:223–243. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000030444.52579.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crofts AR, Meinhardt SW, Jones KR, Snozzi M. The role of the quinone pool in the cyclic electron-transfer chain of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides: a modified Q-cycle mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;723:202–218. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(83)90120-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell P. Possible molecular mechanisms of the protonmotive function of cytochrome systems. J Theor Biol. 1976;62:327–367. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(76)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crofts AR, Hong S, Wilson C, Burton R, Victoria D, Harrison C, Schulten K. The mechanism of ubihydroquinone oxidation at the Qo-site of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827:1362–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victoria D, Burton R, Crofts AR. Role of the -PEWY- glutamate in catalysis at the Qo-site of the cyt bc1 complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1827:365–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenkel AW, Nelson RA. Bacterial chromatophores. Methods Enzymol. 1971;23:256–268. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartron ML, Olsen JD, Sener M, Jackson PJ, Brindley AA, Qian P, Dickman MJ, Leggett GJ, Schulten K, Hunter CN. Integration of energy and electron transfer processes in the photosynthetic membrane of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. In: Cartron Michaël L, Olsen John D, Sener Melih, Jackson Philip J, Brindley Amanda A, Qian Pu, Dickman Mark J, Leggett Graham J, Schulten Klaus, Hunter C Neil., editors. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. Vol. 1837. 2014. pp. 1769–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crofts AR. The mechanism of ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductases of mitochondria and of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. In: Martonosi AN, editor. The Enzymes of Biological Membranes. Plenum Publ Corp; New York: 1985. pp. 347–382. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crofts AR, Guergova-Kuras M, Hong S. Chromatophore heterogeneity explains effects previously attributed to supercomplexes. Photosynth Res. 1998;55:357–362. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colonna R, Dell’Antone P, Azzone GF. Nucleophilic sites in energized mitochondrial membranes. FEBS Lett. 1970;10:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ausländer W, Junge W. Neutral red, a rapid indicator for pH-changes in the inner phase of thylakoids. FEBS Lett. 1975;59:310–315. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saphon S, Crofts AR. Protolytic reactions in photosystem II. A new model for the release of protons accompanying the photooxidation of water. Z Naturforsch. 1977;32c:617–626. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulkidjanian AY, Junge W. Calibration and time resolution of lumenal pH-transients in chromatophores of Rhodobacter capsulatus following a single turnover flash of light: proton release by the cytochrome bc1-complex is strongly electrogenic. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:189–193. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junge W, Ausländer W, Mcgeer A, Runge T. The buffering capacity of the internal phase of thylakoids and the magnitude of the pH changes inside under flashing light. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;546:121–141. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(79)90175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dell’Antone P, Colonna R, Azzone GF. The membrane structure studied with cationic dyes. 1 the binding of cationic dyes to submitochondrial particles and the question of the polarity of the ion-translocation mechanism. Eur J Biochem. 1972;24:553–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb19718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dell’Antone P, Colonna R, Azzone GF. The membrane structure studied with cationic dyes. 2. Aggregation, metachromatic effects and pK shifts. Eur J Biochem. 1972;24:566–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb19719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chance B, Crofts AR, Nishimura M, Price B. Fast membrane H+ binding in the light-activated state of chromatium chromatophores. Eur J Biochem. 1970;13:364–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cogdell RJ, Jackson JB, Crofts AR. The effect of redox potential on the coupling between rapid H+-binding and electron transport in chromatophores from Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. J Bioenerg. 1972;4:211–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01516058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crofts AR, Cogdell RJ, Jackson JB. The mechanism of H+-uptake in Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. In: Quagliariello E, Papa S, Rossi S, editors. Energy Transduction in Respiration and Photosynthesis. Adriatica Editrice; Bari, Italy: 1971. pp. 883–901. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson JB, Crofts AR. Bromothymol blue and bromocresol purple as indicators of pH changes in chromatophores of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Eur J Biochem. 1969;10:226–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogdell RJ, Crofts AR. H+-uptake by chromatophores from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. The relation between rapid H+-uptake and the H+ pump. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;247:264–272. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(74)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cogdell RJ, Prince RC, Crofts AR. Light induced H+-uptake catalysed by photochemical reaction centres from Rhodopseudomonas spheroides R26. FEBS Lett. 1973;35:204–208. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes NG, Crofts AR. The carotenoid shift in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides; the flash-induced change. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;459:492–505. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(77)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes NG, Hunter CN, Niederman RA, Crofts AR. Identification of the pigment pool responsible for the flash-induced carotenoid band shift in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides chromatophores. FEBS Lett. 1980;115:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson JB, Crofts AR. The high energy state in chromatophores from Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. FEBS Lett. 1969;4:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(69)80230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowyer JR, Tierney GV, Crofts AR. Secondary electron transfer in Chromatophores of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata A1a pho− - binary oscillations. FEBS Lett. 1979;101:201–206. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)81326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowyer JR, Meinhardt SW, Tierney GV, Crofts AR. Resolved difference spectra of redox centers involved in photosynthetic electron flow in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata and Rps. sphaeroides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;635:167–186. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(81)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meinhardt SW, Crofts AR. Kinetic and thermodynamic resolution of cytochrome c1 and cytochrome c2 from Rps. sphaeroides. FEBS Lett. 1982;149:223–227. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meinhardt SW, Crofts AR. The role of cytochrome b566 in the electron transfer chain of Rps. sphaeroides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;723:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(83)90120-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes NG, Crofts AR. The carotenoid shift in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides; change induced under continuous illumination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;461:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(77)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson JB, Crofts AR. The kinetics of light induced carotenoid changes in Rhodopseudomonas spheroides and their relation to electrical field generation across the chromatophore membrane. Eur J Biochem. 1971;18:120–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson JB, Crofts AR, Von Stedingk LV. Ion transport induced by light and antibiotics in chromatophores from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Eur J Biochem. 1968;6:41–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saphon S, Gräber P. External proton uptake, internal proton release and internal pH changes in chromatophores from Rps. sphaeroides following single turnover flashes. Z Naturforsch, C: Biosci. 1978;33C:715–722. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong YQ, Junge W. Localized or delocalized protons in photophosphorylation? On the accessibility of the thylakoid lumen for ions and buffers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;722:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crofts AR. Proton-coupled electron transfer at the Qo-site of the bc1 complex controls the rate of ubihydroquinone oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crofts AR, Wang Z. How rapid are the internal reactions of the ubiquinol:cytochrome c2 oxidoreductase? Photosynth Res. 1989;22:69–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00114768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong SJ, Ugulava N, Guergova-Kuras M, Crofts AR. The energy landscape for ubihydroquinone oxidation at the Qo-site of the bc1 complex in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33931–33944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crofts AR, Barquera B, Gennis RB, Kuras R, Guergova-Kuras M, Berry EA. Mechanism of ubiquinol oxidation by the bc1 complex: the different domains of the quinol binding pocket, and their role in mechanism, and the binding of inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15807–15826. doi: 10.1021/bi990962m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crofts AR, Barquera B, Gennis RB, Kuras R, Guergova-Kuras M, Berry EA. Mechanistic aspects of the Qo-site of the bc1 complex as revealed by mutagensis studies, and the crystallographic structure. In: Peschek GA, Loeffelhardt W, Schmetterer G, editors. The Phototrophic Prokaryotes. Plenum Publishing Corporation; New York - London - Washington, D.C. - Boston: 1999. pp. 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crofts AR, Berry EA. Structure and function of the cytochrome bc1 complex of mitochondria and photosynthetic bacteria. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:501–509. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crofts AR, Berry EA, Kuras R, Guergova-Kuras M, Hong S, Ugulava N. Structures of the bc1 complex reveal dynamic aspects of mechanism. In: Garab G, editor. Photosynthesis: Mechanisms and Effects. Kluwer Academic Publ; Dordrecht/Boston/London: 1998. pp. 1481–1486. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crofts AR, Guergova-Kuras M, Huang LS, Kuras R, Zhang Z, Berry EA. The mechanism of ubiquinol oxidation by the bc1 complex: the role of the iron sulfur protein, and its mobility. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15791–15806. doi: 10.1021/bi990961u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crofts AR, Hong SJ, Ugulava N, Barquera B, Gennis R, Guergova-Kuras M, Berry EA. Pathways for proton release during ubihydroquinone oxidation by the bc1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10021–10026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding H, Robertson DE, Daldal F, Dutton PL. Cytochrome bc1 complex [2Fe-2S] cluster and its interaction with ubiquinone and ubihydroquinone at the Qo site: a double-occupancy Qo site model. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3144–3158. doi: 10.1021/bi00127a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moser CC, Page CC, Farid R, Dutton PL. Biological electron transfer. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1995;27:263–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02110096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moser CC, Page CC, Dutton PL. Darwin at the molecular scale: selection and variance in electron tunnelling proteins including cytochrome c oxidase. Philos Trans R Soc. 2006;361:1295–1305. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lhee S, Kolling DR, Nair SK, Dikanov SA, Crofts AR. Modifications of protein environment of the [2Fe-2S] cluster of the bc1 complex: effects on the biophysical properties of the Rieske iron-sulfur protein and on the kinetics of the complex. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9233–9248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zu Y, Couture MMJ, Kolling DRJ, Crofts AR, Eltis LD, Fee JA, Hirst J. The reduction potentials of Rieske clusters: the importance of the coupling between oxidation state and histidine protonation state. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12400–12408. doi: 10.1021/bi0350957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsueh KL, Westler WM, Markley JL. NMR investigations of the Rieske protein from Thermus thermophilus support a coupled proton and electron transfer mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7908–7918. doi: 10.1021/ja1026387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rich PR. Electron and proton transfers through quinones and cytochrome-bc complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;768:53–79. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(84)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crofts AR, Guergova-Kuras M, Ugulava N, Kuras R, Hong S. Proc XIIth Congress of Photosynthesis Research. Brisbane, Australia: 2002. Proton processing at the Qo-site of the bc1 complex of Rhodobacter sphaeroides; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts JA, Kirby JP, Wall ST, Nocera DG. Electron transfer within ruthenium (II) polypyridyl-(salt bridge)-dimethylaniline acceptor-donor complexes. Inorg Chim Acta. 1997;263:395–405. [Google Scholar]