ABSTRACT

The oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis is one of the major periodontal agents and it has been recently hailed as a potential cause of the autoimmune disease rheumatoid arthritis. In particular, the peptidylarginine deiminase enzyme of P. gingivalis (PPAD) has been implicated in the citrullination of certain host proteins and the subsequent appearance of antibodies against citrullinated proteins, which might play a role in the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. The aim of this study was to investigate the extracellular localization of PPAD in a large panel of clinical P. gingivalis isolates. Here we show that all isolates produced PPAD. In most cases PPAD was abundantly present in secreted outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) that are massively produced by P. gingivalis, and to minor extent in a soluble secreted state. Interestingly, a small subset of clinical isolates showed drastically reduced levels of the OMV-bound PPAD and secreted most of this enzyme in the soluble state. The latter phenotype is strictly associated with a lysine residue at position 373 in PPAD, implicating the more common glutamine residue at this position in PPAD association with OMVs. Further, one isolate displayed severely restricted vesiculation. Together, our findings show for the first time that neither the major association of PPAD with vesicles, nor P. gingivalis vesiculation per se, are needed for P. gingivalis interactions with the human host.

KEYWORDS: PPAD, Porphyromonas gingivalis, sorting, secretion, OMVs, OM, RA

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a Gram-negative, anaerobic bacterium and a keystone oral pathogen [1,2]. Albeit mainly studied for its status as causative agent of periodontitis [3], in recent times, newer discoveries have suggested a role for this bacterium in the etiopathogenesis of the autoimmune disease rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [4–9]. RA is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects the synovium, the tissue enveloping the synovial joints, and if untreated leads to loss of mobility [10−12]. Severe inflammatory responses cause synovial membranes thickening and bone resorption which, in turn, result in deformed joints.

The etiology of rheumatoid arthritis has not been fully comprehended, but it appears that loss of tolerance towards citrullinated proteins plays a significant role [4,8,13,14]. Particularly, autoantibodies against citrullinated host proteins, known as ACPAs (anti-citrullinated protein antibodies), have a remarkable specificity for RA [15,16]. This discovery has shed new light on the link between periodontitis and RA. P. gingivalis, in fact, is currently the sole prokaryote reported to secrete an enzyme capable of converting arginine residues to citrulline [4,13,14]. In contrast, humans possess several of such enzymes, collectively called peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs). Remarkably, P. gingivalis' PAD (PPAD) is evolutionary unrelated to human PADs. Despite the shared enzymatic activity, PPAD and the human PADs appear to exhibit different substrate specificities. Particularly, PPAD preferentially citrullinates terminal arginine residues of a polypeptide chain, which hints at a relationship with secreted proteases of P. gingivalis, the so-called gingipains RgpA and RgpB in particular. These gingipains cleave proteins at arginine residues, thereby creating a perfect target for PPAD. Notably, PPAD was previously shown to be present in two variants, an outer membrane (OM)-bound state and a soluble secreted state [17,18]. This distinct feature of PPAD appears directly related to the transport system responsible for its export, the Por secretion system [17,19]. During export, a fraction of the PPAD is attached to the OM via A-LPS anchoring, which involves cleavage of the C-terminal Por-specific signal peptide by the putative sortase PorU [17,20–22]. Moreover, PPAD was proposed to reside also in outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). These secreted nanostructures result from a specific OM blebbing process that, in the case of P. gingivalis, is not yet fully understood [2]. OMVs are generally produced as single bilayer membranous structures for various functions, such as shuttling their cargo of proteins to the outside of the cell or delivering it to targets in the extracellular milieu [23]. For P. gingivalis, the OMVs were suggested to have a role in pathogenesis, considering that their cargo appears to be mainly composed of virulence factors [2,23,24].

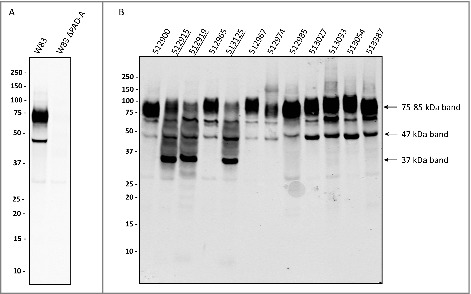

Thus far, it was not known whether clinical P. gingivalis isolates invariably express and secrete PPAD. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the extracellular localization of PPAD in a large panel of clinical P. gingivalis isolates. This was first tested by Western blotting using unfiltered growth medium fractions of 93 clinical isolates and two type strains. In principle, such growth medium fractions contain both soluble secreted proteins and OMV-associated proteins. Indeed, PPAD was detectable in the growth media of all isolates, and the PPAD signal was absent from samples of two genetically engineered PPAD deletion mutants (Figs. 1 and S1). Unexpectedly, two classes of isolates (hereafter referred to as PPAD “sorting types”) were distinguished based on different PPAD banding patterns. The first, most common, sorting type I produces a major PPAD species of ∼75–85-kDa, running as a broad band on lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS)-PAGE, plus a minor PPAD species of ∼47-kDa. Some type I isolates also produce a third PPAD species of ∼60-kDa (Figs. 1 and S1). The PPAD sorting type II, represented by only 9 isolates, displays massively reduced levels of ∼75–85-kDa species. Further, the type II isolates produce the ∼47-kDa species plus a PPAD species of ∼37-kDa. Some also produce relatively small amounts of the aforementioned ∼60-kDa species.

Figure 1.

Distinction of PPAD sorting types I and II P. gingivalis isolates were cultured for four days in BHI medium. Subsequently, bacterial cells were separated from the growth medium, and growth medium fractions, containing OMVs, were used for immunoblotting with PPAD-specific antibodies. (A) P. gingivalis reference strain W83 and the isogenic PPAD deletion mutant. (B) P. gingivalis clinical isolates. Names of sorting type II isolates are underlined. Molecular weights of marker proteins and different PPAD species are indicated.

To verify whether any of the secreted PPAD species are also present in cells of P. gingivalis, we analyzed cells of P. gingivalis isolates belonging to either PPAD sorting type by Western blotting (S2 Fig.). Cells of the type I isolates, displayed only the ∼75–85-kDa species. In contrast, cells of the sorting type II isolates (513324 and 513044) displayed only the ∼37-kDa PPAD species. Of note, cells of both sorting types lack the ∼47-kDa PPAD species detected in growth medium fractions, showing that this species represents a soluble secreted form of PPAD. These findings are fully consistent with the previous reports by Konig et al. [25,26] and Shoji et al. [25,26], who proposed that the 75–85-kDa species represents the A-LPS-modified OM-bound form of PPAD, while the 47-kDa species represents a soluble secreted form of PPAD. The A-LPS modification would explain the thick banding pattern displayed by the 75–85-kDa PPAD species upon LDS-PAGE (Fig. 1).

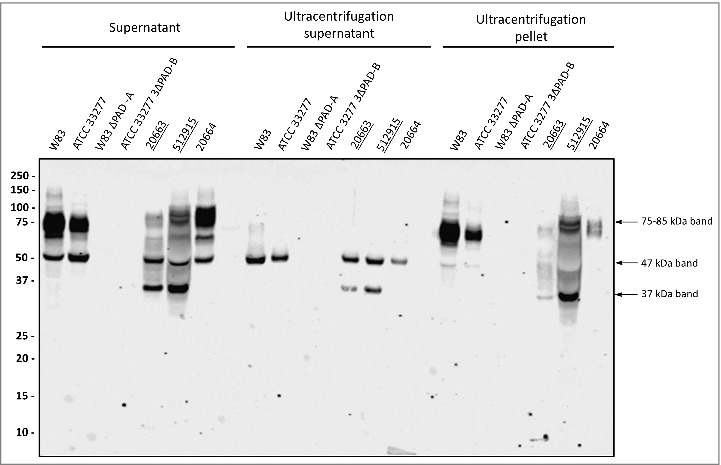

Previous analyses have shown that P. gingivalis secretes OMVs [2,23,24,27]. It is thus conceivable that the secreted 75–85-kDa A-LPS-modified PPAD species is associated with OMVs. To test this idea, we analyzed OMVs collected from spent growth medium fractions by ultracentrifugation for the presence of PPAD. Indeed, the 75–85-kDa species of type I and II isolates was pelleted with the OMVs and no longer detectable in the supernatant after ultracentrifugation (Fig. 2). Consistent with the literature data, the 47-kDa species of PPAD fractionated with the ultracentrifugation supernatant showing that this is a soluble secreted form of PPAD. Notably, the 37-kDa PPAD species displayed a dual localization, being detectable both in the OMV and supernatant fractions (Fig. 2). This OMV association of the 75–85-kDa and 37-kDa PPAD species is consistent with the detection of these species in P. gingivalis cells (S2 Fig.).

Figure 2.

Association of PPAD species with OMVs Growth medium fractions (designated ‘supernatant’) of P. gingivalis sorting type I and II isolates were subject to ultracentrifugation. Subsequently, the supernatant and pellet fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated for Fig. 1. Samples relating to the reference strain W83 and ATCC 33277, the respective PPAD deletion mutants, and sorting type I and II isolates are indicated with names of type II isolates underlined. Molecular weights of marker proteins and different PPAD species are indicated.

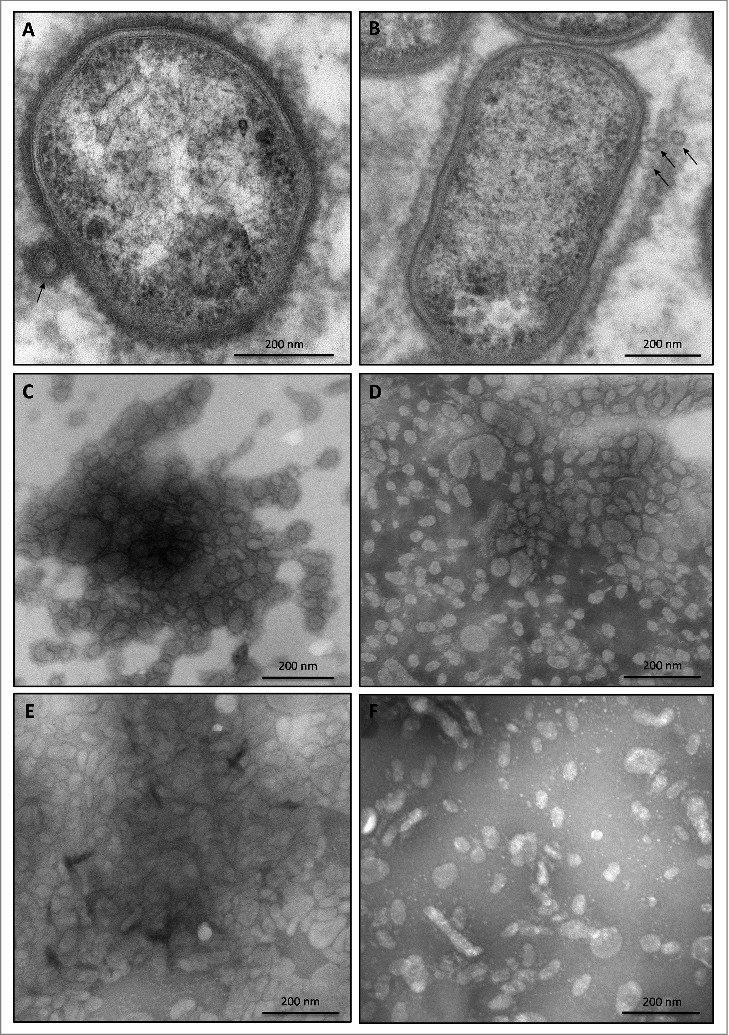

Considering that the presence of the 75–85-kDa species in the medium is associated with OMVs, it was conceivable that the sorting type II might relate to impaired production of OMVs. This was investigated by inspecting the possible presence of OMVs in ultracentrifuged cell-free growth medium fractions of three type II isolates using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). OMVs were observed in all three samples, as was the case for the type strain W83 and a clinical isolate, both belonging to sorting type I (Fig. 3). Of note, the sorting type II isolate MDS33 displayed very low amounts of OMVs, showing that massive vesiculation, as displayed by all other investigated clinical P. gingivalis isolates, is not an essential trait for survival of this pathogen in the human gingiva. Furthermore, observed variations in the vesiculation levels and OMV shapes (Fig. 3) did not correlate with the sorting types of the respective strains.

Figure 3.

OMV formation by sorting type I and II isolates of P. gingivalis Electron micrographs of vesiculating cells of (A) the P. gingivalis type strain W83, and (B) the sorting type II isolate MDS33. Electron micrographs of OMVs collected from (C) strain W83, (D) the sorting type I isolate 505700, and the sorting type II isolates (E) 505759 and (F) 512915.

The strikingly different PPAD banding patterns of the two sorting types prompted further analyses to verify whether other secreted proteins might display similar distinctive features. As shown by Western blotting, the extracellular appearance of the OM protein Omp41 and the secreted gingipains Kgp, RgpA and RgpB did not follow the classification of the PPAD sorting types (S3 and S4 Figs.). Notably, the isolate MDS33 displayed low levels of vesiculation but, for unknown reasons, the levels of Omp41 secreted into the growth medium were still comparable with other isolates. Together, these observations imply that the type I and II sorting types represent a specific shared feature of the respective PPAD proteins.

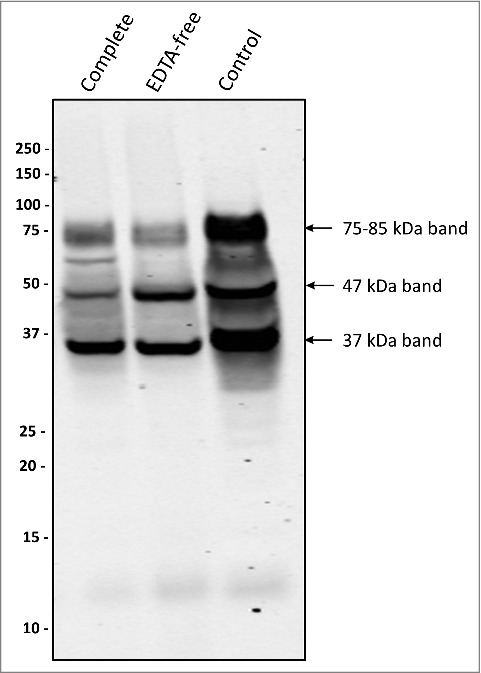

P. gingivalis is renowned for its high proteolytic activity, partially due to its secreted gingipains. As shown by Western blotting, the two sorting types did not display major differences in gingipain secretion (S4 Fig.). To exclude the possibility that the suppressed appearance of the 75–85-kDa PPAD species in the type II isolates is due to proteolytic activity, type II isolates were grown in the presence of EDTA-free or regular protease inhibitors. Intriguingly, this resulted in decreased levels of the secreted 75–85-kDa species, relative to the 47-kDa and 37-kDa species (Figs. 4 and S5), suggesting a reduced export of PPAD or a reduced level of post-translational modification rather than reduced proteolysis. Together, these observations imply that the suppressed appearance of the 75–85-kDa species in type II isolates is probably not due to gingipain activity. Conversely, the possible involvement of proteases that are not inhibited by standard protease inhibitors in a conversion of the 75–85-kDa species to, for example, the 37-kDa species cannot be excluded.

Figure 4.

Protease inhibitors suppress the formation of a 75–85-kDa PPAD species P. gingivalis sorting type II isolate 20663 was grown in the presence or absence of protease inhibitors as indicated. Growth medium fractions, containing OMVs, were analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated for Figure 1. Molecular weights of marker proteins and different PPAD species are indicated.

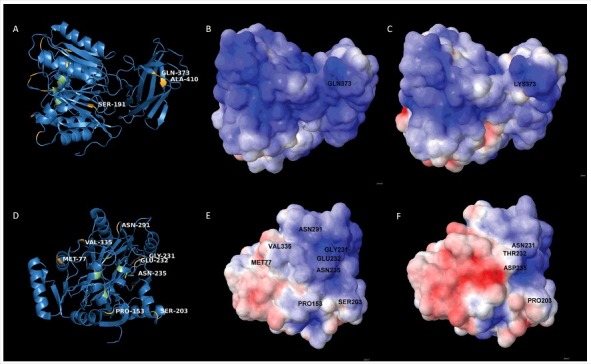

Since the PPAD sorting type is apparently not related to proteolysis or strain-specific differences in OMV formation, we investigated whether particular residues in PPAD can be associated with sorting type I or II. To this end, the nine sorting type II isolates were sequenced and the encoded PPAD proteins were compared to those of previously sequenced type I isolates [28]. This showed a high degree of PPAD conservation (S5 Table) [28]. Residues involved in catalysis (Asp130, His236, Asp238, Asn297 and Cys351) or substrate specificity (Arg152 and Arg154) [29] are invariably present. Compared to the type I strain W83, the highest numbers of PPAD amino acid substitutions are observed in the type II isolates MDS33 and 512919 (S5 Table). However, only the Q373K substitution is distinctive for all identified type II isolates. This implies that Gln373 is needed to produce the dominant 75–85-kDa PPAD species associated with OMVs. Notably, 3D modelling maps Gln373 to the outer surface of the PPAD protein (Fig. 5A), where this residue's side-chain has the potential to interact with other molecules or OMVs. Interestingly, the Q373K substitution alters the electrostatic surface potential of the protein (Fig. 5B and C). Of note, several substitutions observed for type II isolates map to positions that allow interactions with the outer environment. In particular, substitutions at positions 77, 153, 203, 231, 232, 235, 291 and 335 map to the surface of PPAD (Fig. 5D). In fact, these substitutions are located in the vicinity of the major catalytic residue Cys351, suggesting possible alterations in the catalytic activity or substrate specificity of the respective PPAD molecules (Fig. 5D). This is surmised by the massive variations in electrostatic surface potential high-lighted through 3D modeling (Fig. 5E and F).

Figure 5.

Position of amino acid substitutions in PPAD and their impact on the electrostatic potential of the protein (A) 3D-structural ribbon representation of the PPAD protein from P. gingivalis reference strain W83, showing in yellow surface-exposed amino acid residues that have been substituted in PPAD proteins from other P. gingivalis sorting type II isolates. Catalytic residues of PPAD are shown in green. (B and C) Electrostatic potential maps showing, respectively, the PPAD proteins of strain W83 and the sorting type II isolate MDS33 from the same perspective. The two maps display the difference in electrostatic potential (red represents -5 KT/e and blue +5 KT/e), and the respective Gln or Lys residues at position 373 are indicated. (D) 3D-structural ribbon representation of the PPAD protein from P. gingivalis strain W83, showing surface-exposed amino acid residues that have been substituted in other PPAD proteins (marked in yellow) of sorting type II isolates from the perspective of the catalytic site. The catalytic residues are marked in green. (E) Electrostatic potential map of the PPAD protein of strain W83, displaying all the residues subject to substitutions in sorting type II isolates. (F) Electrostatic potential map of the PPAD protein from the sorting type II isolate MDS33.

In conclusion, PPAD is expressed by all 93 investigated P. gingivalis isolates, demonstrating that this is a highly conserved feature of P. gingivalis [28]. Interestingly, we identified two different PPAD sorting types based on the PPAD banding patterns upon LDS-PAGE. Both sorting types produce the 47-kDa soluble secreted form of PPAD. However, the 82 type I isolates produce high levels of a presumably A-LPS-modified 75–85-kDa OMV-associated PPAD species, which is detectable only in very low amounts in the type II isolates. Conversely, the type II isolates produce a 37-kDa form of PPAD that is detectable both in OMVs and in the OMV supernatant after ultracentrifugation. At present, the origin of the 37-kDa species is enigmatic, but it could be related to proteolysis during its export from the cytoplasm. If so, this cleavage is not affected by inhibitors that inactivate the most common classes of proteolytic enzymes, although it is difficult to exclude the possibility that the activity of some proteases was not or only partially inhibited under the present experimental conditions. Importantly, appearance of the 37-kDa species in type II isolates cannot be correlated to the production of gingipains, especially since gingipains are abundantly produced by all type I and II isolates. On the other hand, the levels of the 75–85-kDa PPAD species are associated with a Q373K substitution, where Gln373 is diagnostic for the type I sorting phenotype and Lys373 for the type II phenotype. As the 75–85-kDa species is allegedly A-LPS-modified, our findings implicate Gln373 in this particular modification. In this respect, it is noteworthy that A-LPS modification occurs upon C-terminal cleavage by the sortase-like transpeptidase PorU [17,20–22]. To date, the precise mechanism involved in A-LPS modification is not entirely clear, but the available data suggest that PorU replaces the Por-specific C-terminal signal peptide with an A-LPS-related modification through transpeptidation at a Ser residue [22]. In turn, this implies that the surface-exposed Gln373 residue is probably not a target for PorU-mediated A-LPS modification. Indeed, in a previous study we have shown the presence of unmodified Gln373 containing peptides by mass spectrometry, although these may have been derived from the 47-kDa PPAD species [30]. Moreover, the detection of minor amounts of the 75–85-kDa species in type II isolates suggest that A-LPS modification is not fully impaired when PPAD bears the Q373K substitution. Altogether, these observations imply that Lys373 interferes with the A-LPS modification of PPAD, possibly through the altered surface charge as the lysine side chain is positively charged while that of glutamine is neutral. Although this is an attractive idea, further studies combining site-specific mutagenesis of PPAD and subcellular localization experiments are needed to define the precise roles of Gln373 and Lys373 in the sorting of PPAD.

Lastly, the level of OMV-bound PPAD does not appear to directly correlate with a diagnosis of RA in the host. Yet, it has to be noted that RA is a multi-factorial disease and, as such, the PPAD sorting type of a P. gingivalis isolate might still be a factor that contributes to the overall citrullination burden. In particular, OMVs are generally considered to serve as delivery vehicles for virulence factors that are readily internalized by phagocytic cells, especially neutrophils and macrophages. In turn, this could lead to the presentation of citrullinated peptides, leading to the formation of ACPAs. In this case, sorting type II P. gingivalis isolates would have a lowered propensity for generating ACPAs. This is an intriguing hypothesis that merits further research, because it would mean that the bacterial machinery for A-LPS modification of PPAD could be a druggable target for the fight against RA.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions – 90 P. gingivalis isolates (S1 Table) were collected in Groningen, the Netherlands, from patients with a periodontal diagnosis, of which eight were confirmed to have RA. Additionally, the study isolates included one P. gingivalis isolate from a healthy carrier, and two P. gingivalis type strains (W83 and ATCC 33277), with the respective engineered PPAD deletion mutants [31]. As controls, two unrelated oral pathogens, Prevotella intermedia and Fusobacterium nucleatum, were included. Each isolate was grown anaerobically as previously described [30, the cultures being inoculated with 4 days old colonies on blood agar plates.

Escherichia coli BL21 was cultured aerobically in Lysogeny Broth (LB) at 37°C and with shaking (250 rpm), or on LB agar at 37°C. Lactococcus lactis was grown without shaking in M17 broth supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 5 µg/mL chloramphenicol at 30°C, or on M17 agar plates with the same supplements.

Antibody production – Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised at Eurogentec (Seraing, Liège, Belgium) for detection of PPAD, Omp41, Kgp, and RgpA + RgpB. To this end, the PPAD gene from reference strain W83 was cloned and expressed without its signal sequence in Lactococcus lactis PA1001[31,32], using plasmid pNG4210[33,34] and primers P1LF and P1LR (S2 Table). To raise Omp41-specific antibodies, the omp41 gene of strain W83 was amplified with primers P1F and P1R (S2 Table). To raise Kgp-specific antibodies, the region of the kgp gene from P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 encoding the catalytic domain was amplified with primers P2F and P2R (S2 Table). To raise antibodies recognizing both RgpA and RgpB (hereafter named RgpA/B), the region of the rgpA gene from P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 encoding the catalytic domain of RgpA that is nearly identical to the catalytic domain of RgpB [35,36], was amplified with primers P3F and P3R (S2 Table). The resulting omp41, kgp, rgpA/B fragments were all cloned and expressed in E. coli BL21 using pET26B+. Expression of PPAD in L. lactis was induced overnight with nisin as described [33], while expression of Omp41 or the Kgp and RgpA catalytic domains in E. coli was induced with Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside for 2 h. After induction, cells were collected by centrifugation and disrupted by sonication (L. lactis) or bead-beating (E. coli) in binding buffer (S3 Table). Cell lysates were added to 500 µL of HisLink™ Protein Purification Resin (Promega, USA) and incubated at room temperature for 30–60 min. To remove non-specifically bound proteins, the resin was washed thrice with 10 mL wash buffer (S3 Table) and transferred to a column. Elution was performed by collecting four fractions: two with 1.6 mL of elution buffer 1 and two with 1.6 mL of elution buffer 2 (S3 Table). The eluted proteins in immunization buffer (S3 Table) were used to immunize rabbits. Of note, RgpA/B antibodies binding the catalytic domain of RgpA will also bind RgpB, but the two proteins can be distinguished by virtue of their different molecular weights.

Analysis of secreted proteins – Proteins secreted into the culture medium (2 mL) were collected through 10% TCA precipitation as described [30]. Subsequently, they were separated by LDS-PAGE (NuPAGE gels, Life Technologies) [30]. Western blotting analysis was performed using Amersham™ Protran® 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and antibodies specific for PPAD (GP2448), Omp41 (GP2451), or gingipains. After overnight incubation with 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), membranes were washed with PBS-Tween20 (PBS-T) and incubated with primary anti-PPAD, Omp41, Kgp or RgpA/B antibodies in a 1:10000 dilution. Following one-hour incubation, membranes were washed four times for 5 min with PBS-T before being incubated for 45 min with a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody IRDye® 800CW conjugate (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) at a 1:10000 dilution. Afterward, membranes were washed four times in PBS-T and twice in PBS, before scanning with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Collection of OMVs – To collect OMVs, 2 mL bacterial culture aliquots were centrifuged at 16100 x g, 4°C, for 20 min to separate cells from OMVs in the growth medium. 500 μL aliquots of the resulting supernatant were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 213000 x g, 4°C, for 2 h in an Optima MAX-XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) using an MLA-80 fixed angle rotor. The resulting pellet containing OMVs was resuspended in 500 μL of PBS with 5 mM MgCl2. When needed, the vesicle fraction was concentrated by precipitation with 10% TCA.

Protease inhibition – Proteolytic activity was inhibited by growing bacteria in presence of the cOmplete Mini or cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), according to manufacturer's specifications.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) – Bacteria. 2 mL bacterial culture aliquots were centrifuged at 16100 x g, 4°C, for 20 min. The resulting pellets were resuspended in pre-fixative (S3 Table) for 20 min at room temperature. Subsequently, bacteria were pelleted again and resuspended in fixative (S3 Table) for 2 h. After washing with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, bacteria were pelleted in 2% low-melting-point agarose. After 2 h, 4°C treatment with post-fixative (S3 Table), bacteria were dehydrated using ethanol and embedded in EPON resin (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). 60 nm sections were cut with an ultramicrotome UC7 (Leica, Vienna, Austria) and contrasted using 2% uranyl acetate, followed by Reynolds lead citrate. Images were recorded with a FEI Cm100 transmission electron microscope operated at 80 KV using a Morada digital camera.

OMVs. OMVs were collected from 8 mL bacterial cultures as indicated above. Upon ultracentrifugation, pellets were resuspended in 20 μL PBS. When needed, these samples were further diluted 1:50. 10 μL of vesicle suspension were placed on Formvar coated TEM grids. After 10 min, liquid was drained using filter paper and grids were placed upside down onto drops of 2% ammonium molybdate for 2 min, and transferred to a drop of water for 30 sec. Subsequently, liquid was drained with filter paper and grids were air-dried before TEM examination as specified above.

Sequence analyses – Total DNA from the nine P. gingivalis sorting type II strains was sequenced as described [28]. PPAD gene sequences were retrieved from the nine assembled genomes, seven previously sequenced P. gingivalis genomes [28], and 15 P. gingivalis genomes in GenBank (S4 Table). PPAD genes and their deduced amino acid sequences were aligned using the MAFFT v7 web server [37]. The sequence reads obtained from whole genome sequencing were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive under project PRJEB20287 with accession numbers: ERS1718891, ERS1718892, ERS1718893, ERS1718894, ERS1718895, ERS1718896, ERS1718897, ERS1718898, and ERS1718899.

Modeling of PPAD three-dimensional (3D) structures – 3D structures of PPAD were initially modeled by homology through the online server SWISS-MODEL [38]. To consider possible steric changes in the proteins due to point mutations, geometrical optimizations of the structures were performed using Hyperchem V.8 [39]. This minimization of energy was performed ab initio with the Polak-Ribiere optimization method and 0.1 kcal/(Å·mol) as termination parameter. Quality assessment of final structures was achieved using QMEAN [40] and PROCHECK [41]. Visualization and localization of substitutions were performed in Pymol [42]. To acquire the electrostatic potential surface, Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations were applied to optimized PDB structures using an AMBER force field and the PDB2PQR server [43].

Ethics statement

The bacterial samples used in the present analyses were obtained in a previous study upon written informed consent [28]. This previous study received Institutional Review Board approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (METc UMCG 2011/010). It was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the institutional regulations, and all samples were anonymized.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Center for Dentistry and Oral Hygiene, University Medical Center Groningen and the Graduate School of Medical Sciences, University of Groningen.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no financial and non-financial competing interests in relation to the documented research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ben Giepmans for support and critically reading the manuscript.

References

- [1].McGraw WT, Potempa J, Farley D, et al.. Purification, characterization, and sequence analysis of a potential virulence factor from Porphyromonas gingivalis, peptidylarginine deiminase. Infect Immun. 1999;67(7):3248–3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gui MJ, Dashper SG, Slakeski N, et al.. Spheres of influence: Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2015;31(5):365–78. doi: 10.1111/omi.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yang HW, Huang YF, Chou MY. Occurrence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythensis in periodontally diseased and healthy subjects. J Periodontol. 2004;75(8):1077–1083. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Quirke AM, Lugli EB, Wegner N, et al.. Heightened immune response to autocitrullinated Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase: A potential mechanism for breaching immunologic tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):263–269. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].de Pablo P, Dietrich T, McAlindon TE. Association of periodontal disease and tooth loss with rheumatoid arthritis in the US population. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(1):70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Detert J, Pischon N, Burmester GR, et al.. The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(5):218. doi: 10.1186/ar3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].de Smit M, Westra J, Vissink A, et al.. Periodontitis in established rheumatoid arthritis patients: A cross-sectional clinical, microbiological and serological study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(5):R222. doi: 10.1186/ar4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].de Smit MJ, Brouwer E, Vissink A, et al.. Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis; a possible link via citrullination. Anaerobe. 2011;17(4):196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].de Smit MJ, Brouwer E, Westra J, et al.. Effect of periodontal treatment on rheumatoid arthritis and vice versa. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2012;119(4):191–197. doi: 10.5177/ntvt.2012.04.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Laroche D, Pozzo T, Ornetti P, et al.. Effects of loss of metatarsophalangeal joint mobility on gait in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(4):435–440. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2001;358(9285):903–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pischon N, Pischon T, Kroger J, et al.. Association among rheumatoid arthritis, oral hygiene, and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2008;79(6):979–986. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Routsias JG, Goules JD, Goules A, et al.. Autopathogenic correlation of periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(7):1189–1193. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mangat P, Wegner N, Venables PJ, et al.. Bacterial and human peptidylarginine deiminases: Targets for inhibiting the autoimmune response in rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):209. doi: 10.1186/ar3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Avouac J, Gossec L, Dougados M. Diagnostic and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(7):845–851. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.051391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nishimura K, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, et al.. Meta-analysis: Diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(11):797–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sato K, Yukitake H, Narita Y, et al.. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis proteins secreted by the por secretion system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;338(1):68–76. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Glew MD, Veith PD, Peng B, et al.. PG0026 is the C-terminal signal peptidase of a novel secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(29):24605–24617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.369223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McBride MJ, Zhu Y. Gliding motility and por secretion system genes are widespread among members of the phylum bacteroidetes. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(2):270–278. doi: 10.1128/JB.01962-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shoji M, Sato K, Yukitake H, et al.. Por secretion system-dependent secretion and glycosylation of Porphyromonas gingivalis hemin-binding protein 35x. PLoS One 2011;6(6):e21372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lasica AM, Ksiazek M, Madej M, et al.. The type IX secretion system (T9SS): Highlights and recent insights into its structure and function. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:215. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Veith PD, Glew MD, Gorasia DG, et al.. Type IX secretion: The generation of bacterial cell surface coatings involved in virulence, gliding motility and the degradation of complex biopolymers. Mol Microbiol. 2017;106(1):35–53. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xie H. Biogenesis and function of Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(9):1517–1527. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Veith PD, Chen YY, Gorasia DG, et al.. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles exclusively contain outer membrane and periplasmic proteins and carry a cargo enriched with virulence factors. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(5):2420–2432. doi: 10.1021/pr401227e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Konig MF, Paracha AS, Moni M, et al.. Defining the role of Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase (PPAD) in rheumatoid arthritis through the study of PPAD biology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74(11):2054–61. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shoji M, Ratnayake DB, Shi Y, et al.. Construction and characterization of a nonpigmented mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis: Cell surface polysaccharide as an anchorage for gingipains. Microbiology 2002;148(Pt 4):1183–1191. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ho MH, Chen CH, Goodwin JS, et al.. Functional advantages of Porphyromonas gingivalis vesicles. PLoS One 2015;10(4):e0123448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gabarrini G, de Smit M, Westra J, et al.. The peptidylarginine deiminase gene is a conserved feature of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13936. doi: 10.1038/srep13936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Montgomery AB, Kopec J, Shrestha L, et al.. Crystal structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase: Implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1255–1261. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Stobernack T, Glasner C, Junker S, et al.. Extracellular proteome and citrullinome of the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(12):4532–4543. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wegner N, Lundberg K, Kinloch A, et al.. Autoimmunity to specific citrullinated proteins gives the first clues to the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233(1):34–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Neef J, Koedijk DG, Bosma T, et al.. Efficient production of secreted staphylococcal antigens in a non-lysing and proteolytically reduced Lactococcus lactis strain. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(24):10131–10141. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6030-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hoekstra H, Romero Pastrana F, Bonarius HPJ, et al.. A human monoclonal antibody that specifically binds and inhibits the staphylococcal complement inhibitor protein SCIN. Virulence.2017:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Neef J, Milder FJ, Koedijk DG, et al.. Versatile vector suite for the extracytoplasmic production and purification of heterologous his-tagged proteins in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(21):9037–9048. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6778-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska J, Kordula T, Pavloff N, et al.. Genetic variation of Porphyromonas gingivalis genes encoding gingipains, cysteine proteinases with arginine or lysine specificity. Biol Chem. 1998;379(2):205–211. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Olczak T, Simpson W, Liu X, et al.. Iron and heme utilization in Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29(1):119–144. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, et al.. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, et al.. SWISS-MODEL: Modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Web Server issue):W252–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hypercube HyperChem™, 1115 NW 4th street, gainesville, florida 32601, USA. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Benkert P, Kunzli M, Schwede T. QMEAN server for protein model quality estimation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W510–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, et al.. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schrödinger The PyMOL molecular graphics system 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, et al.. PDB2PQR: An automated pipeline for the setup of poisson-boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W665–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]