Abstract

The identification of germplasm resources is an important aspect of sugarcane breeding. The aim of this study was to introduce a new method for identifying Saccharum spontaneum and its progeny. First, we cloned and sequenced nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (nrDNA-ITS) sequences from 20 Saccharum germplasms. Analysis of these nrDNA-ITS sequences showed a stable mutation at base 89. Primers (FO13, RO13, FI16, and RI16) were then designed for tetra-primer amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) PCR based on mutations at base 89 of the nrDNA-ITS sequence. An additional 71 Saccharum germplasms were identified using this tetra-primer ARMS PCR method, which confirmed that the method using the described primers successfully identified Saccharum spontaneum and progeny. These results may help improve the efficiency of modern molecular breeding of sugarcane and lay a foundation for identification of sugarcane germplasms and the relationships among them.

Introduction

Sugarcane is an important sugar and energy crop worldwide. Sugarcane plants belong to the grass family Gramineae, genus Saccharum, and related plants in this family include Miscanthus, Sclerostachya, Erianthus, and Narenga. The Saccharum genus consists of six species, including Saccharum officinarum (2n = 80), S. sinense (2n = 112–120), S. barberi (2n = 82–124), S. edule (2n = 60, 70, 80), and two wild species, S. robustum (2n = 60–120) and S. spontaneum (2n = 40–128) [1]. S. barberi and S. sinense are secondary species derived from hybridization of S. officinarum and S. spontaneum [2]. Moreover, S. sinense, S. barberi, S. robustum, S. spontaneum, and S. officinarum are important parental resources in sugarcane breeding [3]. Sugarcane cultivars are multiple interspecific hybrids and highly heterogeneous, and almost all contain some S. spontaneum genetic material at levels up to 10% of all chromosomes [4].

Internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) contain ITS1, 5.8s rDNA, and ITS2 [5]. In recent years, several features of nrDNA-ITS have made a useful tool for evaluating and analyzing evolutionary relationships at the subspecies level, including rich variances and rapid evolutionary rate, as well as simple PCR amplification and sequencing [6–8]. In view of these features, Yang et al. analyzed the nrDNA-ITS sequence characteristics of 19 S. spontaneum germplasms and 11 local sugarcane varieties [9]. The results showed that 11 S. spontaneum germplasms could be divided into several branches, and that local sugarcane varieties were closely related to S. spontaneum. Moreover, the ITS1 sequence could be used as a DNA barcode to further study the genetic diversity of Saccharum and related genera. Liu et al. analyzed differences among nrDNA-ITS sequences from 62 different multiple S. spontaneum materials and showed that 4 species had high variation, especially the nonuploid and decaploid population [10].

As a third-generation molecular marker, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are highly stable and widely used for studies of crop molecular genetics [11]. Due to the limited availability of sugarcane genomic maps, research on SNPs in sugarcane lags behind that of rice, rapeseed, and other crops [12]. SNPs for many crops have been discovered through analysis of nrDNA-ITS sequences and in turn have served as valuable molecular markers to identify interspecies germplasms [13] that can contribute to strategies for molecular breeding of crops [14]. Tetra-primer amplification refractory mutation system PCR (tetra-primer ARMS PCR) is a derivative technique based on common PCR that can be specifically used to detect SNPs [15]. Tetra-primer ARMS PCR is rapid, simple, and economical. According to the SNP site, the tetra-primer ARMS PCR technique has been used to identify various germplasm genotypes in rice, wheat, capsicum, and other crops [16–18].

Based on previous studies on nrDNA-ITS in sugarcane germplasms, the tetra-primer ARMS PCR technique can be used to analyze genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships in interspecific and intergenus samples [9, 10, 19]. However, studies exploring the identification and use of SNPs as molecular markers in Saccharum breeding have not been performed. As such, we cloned, sequenced, and analyzed nrDNA-ITS sequences of 20 Saccharum germplasms to identify a stable SNP. Based on the SNP site, primers were designed according to the principles of tetra-primer ARMS PCR. PCR of 71 materials was performed to identify the presence of Saccharum spontaneum genetic material. This study provides a foundation for improving the efficiency of modern molecular breeding of sugarcane and a molecular basis for identifying sugarcane germplasms.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

In this study, 20 clones were selected for nrDNA-ITS sequencing, including 5 S. officinarum, 5 S. robustum, and 15 different multiple S. spontaneum samples that contained octoploid, nonuploid, decaploid, dodecaploid, and tridecaploid S. spontaneum (Table 1). A total of 71 clones were selected for testing and analysis of the specificity of tetra-primer ARMS PCR primers that we developed and designed, including 5 S. officinarum and 3 F1 (S. officinarum×S. spontaneum), which all have similar morphology to S. officinarum, 6 S. robustum, 43 S. spontaneum, 3 S. sinense, 3 S. barberi, 3 sugarcane cultivars and 5 F1 (S. officinarum×S. robustum) materials (Table 2).

Table 1. Plant materials for cloning and sequencing of nrDNA-ITS sequences.

| No. | Clone name | Species name | Ploidy | Number of chromosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Badila | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 2 | VN cattle cane | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 3 | Loethers | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 4 | Crystalina | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 5 | S. Cheribon | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 6 | 57NG208 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 7 | 51NG63 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 8 | NG77-004 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 9 | 28NG21 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 10 | Daye | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 11 | YN75-2-11 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 12 | YN82-110 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 13 | YN83-160 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 14 | FJ89-1-1 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 15 | YN83-201 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 16 | YN82-44 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 17 | YN83-171 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 18 | GZ78-2-28 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 19 | FJ88-1-13 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 20 | FJ89-1-19 | Saccharum spontaneum | tridecaploid | 104 |

Table 2. Plant materials used for identifying genetic material from Saccharum spontaneum with tetra-primer ARMS PCR.

| No. | Clone name | Species name | Ploidy | Number of chromosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Badila | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 2 | VN cattle cane | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 3 | Loethers | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 4 | Crystalina | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 5 | S. Cheribon | Saccharum officinarum | octoploid | 80 |

| 6 | Muckche | F1(S. officinarum×S. spontaneum) | octoploid | 141–143 |

| 7 | Baimeizhe | F1(S. officinarum×S. spontaneum) | octoploid | 104–106 |

| 8 | Cana Blanca | F1(S. officinarum×S. spontaneum) | octoploid | 113–115 |

| 9 | 28NG21 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 10 | 51NG63 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 11 | 51NG3 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 12 | Daye | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 13 | 57NG208 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 14 | NG77-004 | Saccharum robustum | octoploid | 80 |

| 15 | YN75-2-11 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 16 | YN83-160 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 17 | YN83-225 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 18 | YN82-58 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 19 | YN4 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 20 | YN83-238 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 21 | Vietnam-3 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 22 | YN82-9 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 23 | YN-mengzi | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 24 | YN84-268 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 25 | YN82-110 | Saccharum spontaneum | octoploid | 64 |

| 26 | GZ78-1-11 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 27 | YN76-1-16 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 28 | FJ89-1-11 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 29 | YN82-50 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 30 | SC92-42 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 31 | FJ89-1-1 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 32 | YN83-201 | Saccharum spontaneum | nonuploid | 72 |

| 33 | SC88-49 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 34 | FJ89-1-21 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 35 | YN76-1-24 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 36 | YN75-2-35 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 37 | SC79-2-16 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 38 | SC79-1-26 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 39 | YN83-171 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 40 | Wenshan cane | Saccharum sinense | Unknown | Unknown |

| 41 | Uba | Saccharum sinense | Unknown | 116–118 |

| 42 | GD-sinense | Saccharum sinense | Unknown | Unknown |

| 43 | Nagans | Saccharum barberi | Unknown | Unknown |

| 44 | Pansahi | Saccharum barberi | Unknown | Unknown |

| 45 | Saretha | Saccharum barberi | Unknown | 91–92 |

| 46 | ROC10 | Cultivars | Unknown | Unknown |

| 47 | ROC22 | Cultivars | Unknown | Unknown |

| 48 | CP84-1198 | Cultivars | Unknown | Unknown |

| 49 | FJ92-1-11 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 50 | Heqing | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 51 | YN75-2-35 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 52 | GD-16 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 53 | GD-60 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 54 | GD-71 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 55 | YN82-44 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 56 | Ledong-1 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 57 | Xundian | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 58 | GZ78-1-5 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 59 | GZ79-1-4 | Saccharum spontaneum | decaploid | 80 |

| 60 | FJ88-1-13 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 61 | GZ78-2-28 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 62 | FJ-HuiAn | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 63 | FJ89-1-16 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 64 | GD-30 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 65 | FJ89-1-18 | Saccharum spontaneum | dodecaploid | 96 |

| 66 | FJ89-1-19 | Saccharum spontaneum | tridecaploid | 104 |

| 67 | RL12-38-1 | F1(S. officinarum×S. robustum) | Unknown | Unknown |

| 68 | RL12-38-5 | F1(S. officinarum×S. robustum) | Unknown | Unknown |

| 69 | RL12-38-76 | F1(S. officinarum×S. robustum) | Unknown | Unknown |

| 70 | RL12-38-81 | F1(S. officinarum×S. robustum) | Unknown | Unknown |

| 71 | RL12-38-84 | F1(S. officinarum×S. robustum) | Unknown | Unknown |

Reagents and materials

Takala Ex Taq® polymerase, Takala LA Taq® polymerase, PMD19-T vector, and E. coli DH5α competent cells were obtained from Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian of China). Primers were synthesized by the Beijing Genomics Institute (Beijing, China).

Genomic DNA extraction

Young leaves from different sugarcane species were collected and powdered after freezing in liquid nitrogen. Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves using a traditional CTAB method that was performed according to Porebski et al. [20].

Cloning and sequencing

The nrDNA-ITS sequences from 20 clones (Table 1) were amplified using the universal primers ITS1 and ITS4 (ITS1: TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG; ITS4: TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) [21]. The PCR reaction mixtures were prepared on ice (Table 3) and carried out in a thermal cycler (ABI, 9902, USA). The reaction sequences were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 54°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 10 s. A final extension was conducted at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were tested by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using an Omega EZNA gel extraction kit. The purified products were then cloned into a PMD19-T vector and transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells. Recombinant clones were grown in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL). Five clones per sample were selected for sequencing by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Table 3. nrDNA-ITS PCR reaction mixture.

| Components | Volume (μL) |

|---|---|

| ddH2O | 13.9 |

| 10× LA buffer (Mg2+ plus) | 2.0 |

| dNTP (2.5 mM each) | 1.6 |

| ITS1 (10 μM) | 0.8 |

| ITS4 (10 μM) | 0.8 |

| Template (gDNA; 50 ng/μL) | 0.8 |

| LA Taq (5 U/μL) | 0.1 |

| Total volume | 20.0 |

Sequence analysis

DNA sequence homology was estimated using a nucleotide BLAST tool in the NCBI database. All DNA sequences were analyzed by DNAMAN 6.0 and BioEdit 7.0.9.0 to obtain variable site information.

Primer design

Optimized primers for PCR were designed according to the design principle of tetra-primer ARMS PCR primers. Specific reference to the design method for tetra-primer ARMS PCR primers is made in Medrano and de Oliveira [22].

Tetra-primer ARMS PCR procedure

Tetra-primer ARMS PCR of 71 samples (Table 2) was performed using the primers FO13, RO13, FI16, and RI16 (FO13: GTTTTTGAACGCAAG TTGCGCCCGAGGC; RO13: AATTCGGGCGACGAAGCCACCCGATTCT; FI16: GCCGGCGCATCGGC CCTAAGGACCTAT; RI16: GAGCGGCTATGCGCTGCGGTGCTTCT). Tetra-primer ARMS PCR reaction mixtures were prepared on ice (Table 4) and carried out in a thermal cycler (ABI, 9902, USA). The reaction conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 6 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 78°C for 20 s for one cycle and descending by 1°C for each subsequent 20 s cycle, 72°C for 20 s; the reaction ended with 24 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 71°C for 10 s, 72°C for 10 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were tested by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 4. Tetra-primer ARMS PCR mixtures.

| Components | Volume (μL) |

|---|---|

| ddH2O | 1.4 |

| 2×GC buffer | 10.0 |

| dNTP (2.5 mM each) | 2.4 |

| Dimethylsulphoxide | 0.8 |

| FO13 (5 μM) | 1.6 |

| RO13 (5 μM) | 1.2 |

| FI16 (5 μM) | 0.4 |

| RI16 (5 μM) | 1.6 |

| Template (gDNA; 50 ng/μL) | 0.4 |

| Ex Taq (5 U/μL) | 0.2 |

| Total volume | 20.0 |

Results

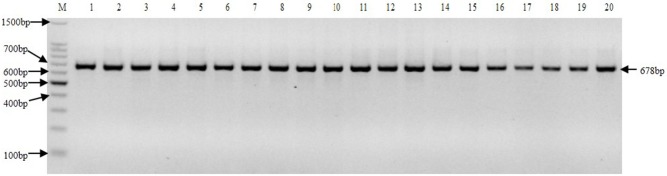

nrDNA-ITS PCR

The nrDNA-ITS sequences of different samples were obtained by PCR with ITS1 and ITS4 primers. The nrDNA-ITS PCR product from each material tested appeared in the electrophoresis map as a single, intense 678 bp band (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Electrophoretogram of nrDNA-ITS PCR products.

M: 100 bp DNA ladder marker. Lanes 1–5: Badila, VN cattle cane, Loethers, Crystalina, Cheribon, respectively, belong to S. officinarum. Lanes 6–10: 57NG208, 51NG63, NG77-004, 28NG21, Daye, respectively, belong to S. robustum. Lanes 11–20: YN75-2-11, YN82-110, YN83-160, FJ89-1-1, YN83-201, YN82-44, YN83-171, GZ78-2-28, FJ88-1-13, FJ89-1-19, respectively, belong to S. spontaneum.

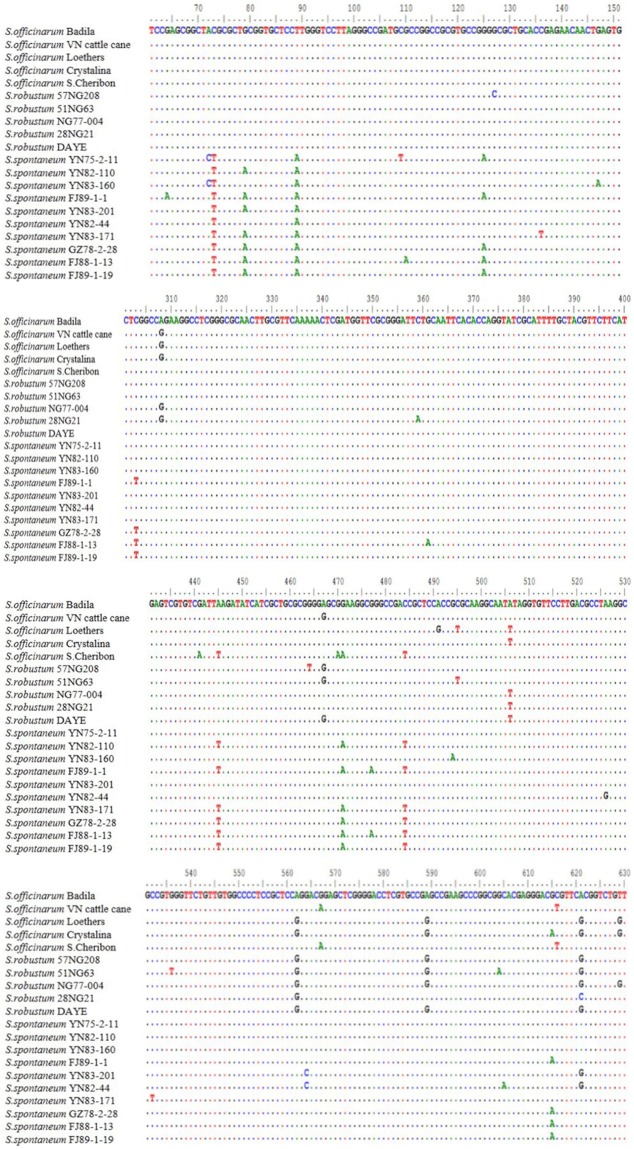

Sequence analysis

All of the clone sequences were analyzed using the BLAST tool in the NCBI database. The homology of all cloned sequences with other germplasm nrDNA-ITS sequences of sugarcane was >98%, which indicated that the clone sequences contained nrDNA-ITS sequences and were highly conserved. All clone sequences were analyzed using DNAMAN 6.0 and BioEdit 7.0.9.0 to obtain variable site information. At least five samples had mutations at bases 73, 79, 89, 125, 308, 445, 471, 484, 506, 562, 589, 615, and 621 (Fig 2). Among all mutations, those at base 73 and 89 were in a regular form because the mutation occurred only in S. spontaneum clones (Fig 2). However, only the mutation at base 89 was conserved for 10 S. spontaneum clones, which could be a good target region of tetra-primer ARMS PCR.

Fig 2. Analysis of nrDNA-ITS sequences.

“······” represents sequences that are identical to that of Badila. Only base mutations are shown.

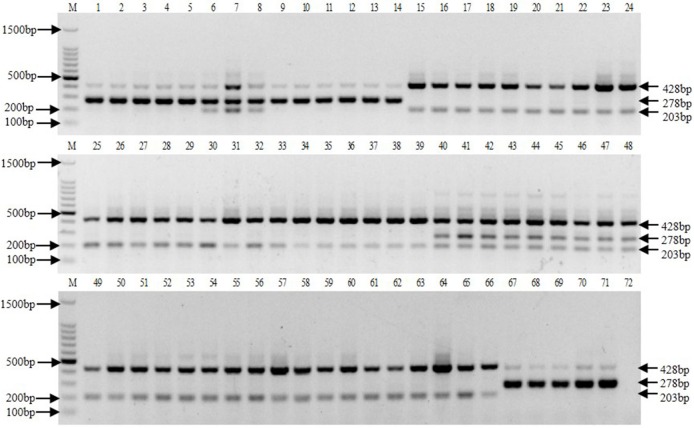

Tetra-primer ARMS PCR

A total of 71 Saccharum genus germplasm materials were amplified around base 89 using tetra-primer ARMS PCR. Tetra-primer ARMS PCR results showed a 428 bp common electrophoretic band in all materials tested, of which S. spontaneum had a 203 bp-specific electrophoretic band, whereas S. officinarum and S. robustum had a 278 bp-specific electrophoretic band (Fig 3). Considering the bands for ROC10, ROC22, and CP84-1196, we successfully identified the presence of S. spontaneum genetic material. RL12-38-1, RL12-38-5, RL12-38-76, RL12-38-81, and RL12-38-84 yielded two bands (428 bp and 278 bp), which indicated the absence of S. spontaneum genetic material. Moreover, analysis of electrophoretic bands allowed for the determination that Muckche, Baimeizhe, and Canablanca were F1 (S. officinarum × S. spontaneum) (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Electrophoretogram of tetra-primer ARMS PCR products.

M: 100 bp DNA ladder marker. Lanes 1–5: Badila, VN cattle cane, Loethers, Crystalina, and S. Cheribon, respectively, are S. officinarum. Lanes 6–8: Muckche, Baimeizhe, and Canablanca, respectively, are F1 generations produced between S. officinarum and S. spontaneum. Lanes 9–14: 28NG21, 51NG63, 51NG3, Daye, 57NG208, and NG77-004, respectively, are S. robustum. Lanes 15–39: YN75-2-11, YN83-160, YN83-225, YN82-58, YN4, YN83-238, Vietnam-3, YN82-9, YN-mengzi, YN84-268, YN82-110, GZ78-1-11, YN76-1-16, FJ89-1-11, YN82-50, SC92-42, FJ89-1-1, YN83-201, SC88-49, FJ89-1-21, YN76-1-24, YN75-2-35, SC79-2-16, SC79-1-26, and YN83-171, respectively, are S. spontaneum. Lanes 40–42: Wenshan cane, Uba, and GD-sinense, respectively, are S. sinense. Lanes 43–45: Nagans, Pansahi, and Saretha, respectively, are S. barberi. 46–48: ROC10, ROC22, and CP84-1196, respectively, are cultivars. Lanes 49–66: FJ92-1-11, Heqing, YN75-2-35, GD-16, GD-60, GD-71, YN82-44, Ledong-1, Xundian, GZ78-1-5, GZ79-1-4, FJ88-1-13, GZ78-2-28, FJ-HuiAn, FJ89-1-16, GD-30, FJ89-1-18, and FJ89-1-19, respectively, are S. spontaneum. Lanes 67–71: RL12-38-1, RL12-38-5, RL12-38-76, RL12-38-81, and RL12-38-84, respectively, are F1 generations produced between S. officinarum and S. robustum. Lane 72: H2O.

Discussion

In this study, we found for the first time that base 89 was a stable base mutation in the nrDNA-ITS sequence of the Saccharum genus and was present in S. spontaneum genetic material. We thus designed primers for tetra-primer ARMS PCR based on this nrDNA-ITS sequence SNP. After optimization and identification, the primers FO13, RO13, FI16, and RI16 were found to be suitable for identification of S. spontaneum genetic material and its progeny. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first instance of the use of tetra-primer ARMS PCR to identify S. spontaneum genetic signatures in the Saccharum genus. These findings will be valuable for classifying sugarcane germplasms and will improve sugarcane hybridization breeding efficiency.

In angiosperms, this entire ITS region (ITS1+5.8S+ITS2) can be easily amplified using universal primers that recognize conserved coding regions to produce a 700 bp amplicon [23]. Here, a 678 bp fragment was amplified using the general primers ITS1 and ITS4 that cover the entire ITS sequence. This ITS sequence is not only widely used for germplasm classification and phylogeny analysis, but also for identification of germplasm resources in sample plants. Previous studies have suggested that this ITS sequence has higher conservation than the medium-height repetitive sequence and non-coded sequences, and that the mutation rate is relatively rapid compared with the coded gene sequence [24]. In allopolyploid plants, ITS sequence evolution is complex, such that ancestral ITS sequences can coexist in some offspring, but in other offspring may evolve in another direction [25, 26]. For example, in the polyploid plants of wheat, ancestral nrDNA-ITS sequences coexist in the offspring [27]. In this study, tetra-primer ARMS PCR results showed that the hybrid generation generated between S. officinarum and S. spontaneum yielded three bands (428 bp, 278 bp, 203 bp), the offspring generated between S. officinarum and S. robustum yielded two bands (428 bp, 278 bp), which respectively revealed parents’ traits. Therefore, we found that the ancestral nrDNA-ITS sequences could coexist in the offspring in the hybrid process of sugarcane. Our sequence analysis in this study indicated that the nrDNA-ITS sequence in sugarcane is relatively conserved. Moreover, the SNPs we identified were highly stable genetic markers. Therefore, the primers we developed for tetra-primer ARMS PCR could be used for accurate and reliable identification of S. spontaneum genetic material and progeny in the Saccharum genus.

The identification of Saccharum germplasm collections is mainly based on morphological observation, which can result in misclassification. In recent years, several molecular markers, such as SSR, AFLP, ISSR, and RAPD, have been applied for identification of Saccharum germplasms and progeny identification [28–31]. Many specific bands can be obtained from the progeny of hybrid offspring using these molecular markers, which contribute significantly to the separation and identification of sugarcane hybrids and germplasms. However, these molecular markers cannot intuitively identify sugarcane germplasms, as they produce multiple amplification bands that complicate interpretation and quantification. Of course, single-copy gene marker had been applied in phylogenetics in many plants with the development of sequencing technology [32, 33]. Compare with nrDNA-ITS sequence, the use of a single-copy gene mostly demands development of PCR primers specific for the taxonomic group of interest [34]. Moreover, this can result in the inclusion of paralogous copies in phylogenetic studies in the polyploid plans, resulting in wrong taxon relationships. To avoid this problem, the single-copy nuclear genes that occured mostly only with a single copy in the haploid genome might be preferable in phylogenetic analyses and identification of different species [35]. Therefore, selection of single-copy gene marker is an issue at present, especially in the polyploid plant. Because the sugarcane is an allopolyploids plant, its genome research is not yet complete and it is very difficult to obtain the haploid of sugarcane at present. Thus, selection of a single-copy gene as molecular marker is very difficult in sugarcane. In a more visual identification of sugarcane germplasm materials, Piperidis et al. used genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) to show that Kokea, Muntok Java, and Bourbonriet suriname were not S. officinarum, but instead were hybridized progeny of S. officinarum and S. spontaneum [36]. Moreover, many breeders believed that Muckche, Canablanca, and Baimeizhe were S. officinarum based on similar morphology. However, in 2016 Wang et al. identified 10 S. officinarum types using GISH technology and found that Muckche, Canablanca, and Baimeizhe were in fact hybridized progeny of S. officinarum and S. spontaneum [37]. These results are consistent with our study, which supports the reliability of the molecular markers we identified. Based on tetra-primer ARMS PCR results, we easily distinguished S. spontaneum and other Saccharum germplasm materials in this study. Moreover, tetra-primer ARMS PCR using the primers FO13, RO13, FI16, and RI16 to identify S. spontaneum and progeny is simpler and less time-consuming than GISH.

The breeding of a sugarcane variety typically requires approximately 10 years. Historically, the breeding process could not be accelerated because plants could not be selected early in the seedling stage due to a lack of molecular markers. The tetra-primer ARMS PCR technology developed in this study could have broad applications for sugarcane breeding in the future. This approach could address the problem of early selection and identify whether seedlings incorporate S. spontaneum genetic material. Germplasms from plants thought to include S. spontaneum as a predecessor could be identified using tetra-primer ARMS PCR technology to determine whether such plants are indeed hybridized progeny of S. officinarum and S. spontaneum.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Germplasm Repository of Sugarcane, the Sugarcane Research Institute of the Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Guangzhou Sugarcane Industry Research Institute for providing the plant materials used in this study. We greatly appreciate Bioscience Editing Solutions for critically reading this paper and providing helpful suggestions.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571730 and 31401440) and was supported by the science and technology major project of the Fujian Province of China (2015NZ0002-2) and special fund for scientific and technological innovation of the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (KFA17168A). This project was also supported by an open project of the Key Laboratory of Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agricultural Biological Resources (SKLCUSA-b201606). These funding institutions played no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Irvine JE. Saccharum species as horticultural classes. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1999;98(2):186–94. doi: 10.1007/s001220051057 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selvi A, Nair NV, Noyer JL, Singh NK, Balasundaram N, Bansal KC, et al. AFLP analysis of the phenetic organization and genetic diversity in the sugarcane complex, Saccharum and Erianthus. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2006;53(4):831–42. doi: 10.1007/s10722-004-6376-6 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JS, Schnell RJ, Power EJ, Douglas SL, Kuhn DN. Analysis of clonal germplasm from five Saccharum species: S. barberi, S. robustum, S. officinarum, S. sinense and S. spontaneum. A study of inter- and intra species relationships using microsatellite markers. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2007;54(3):627–48. doi: 10.1007/s10722-006-0035-z [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinz DJ. Sugarcane improvement through breeding. Developments in Crop Science. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiba M, Kondo K, Miki E, Yamaji H, Morota T, Terabayashi S, et al. Identification of medicinal Atractylodes based on ITS sequences of nrDNA. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2006;29(2):315–20. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dkhar J, Kumaria S, Rao SR, Tandon P. Sequence characteristics and phylogenetic implications of the nrDNA internal transcribed spacers (ITS) in the genus Nymphaea with focus on some Indian representatives. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2012;298(1):93–108. doi: 10.1007/s00606-011-0526-z [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koloren O, Koloren Z, Eker Si. Molecular phylogeny of Artemisia species based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of 18S-26S rDNA in Ordu Province of Turkey. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 2016;30(5):1–6. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2016.1188674 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarkson JJ, Pennington TD, Chase MW, Haynes G, Engstrand R, Kaye M, et al. Phylogenetic relationships in Trichilia (Meliaceae) based on ribosomal its sequences. Phytotaxa. 2016;259(1):6 doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.259.1.4 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang CF, Yang LT, Li YR, Zhang GM, Zhang CY, Wang WZ. Sequence Characteristics and Phylogenetic Implications of the nrDNA Internal Transcribed Spacers (ITS) in Protospecies and Landraces of Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.). Sugar Tech. 2016;18(1):8–15. doi: 10.1007/s12355-014-0355-9 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu XL, Li XJ, Liu HB, Xu CH, Lin XQ, Li CJ, et al. Phylogenetic Analysis of Different Ploidy Saccharum spontaneum Based on rDNA-ITS Sequences. Plos One. 2016;11(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brookes AJ. The essence of SNPs. Gene. 1999;234(2):177–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00219-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang S, Deng L, Mei G, Li J, Lu K, Wang H, et al. Identification of genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms in allopolyploid crop Brassica napus. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):717 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo YM, Zhang WM, Ding XY, Shen J, Bao SL, Chu BH, et al. SNP marker and allele-specific diagnostic PCR for authenticating herbs of Perilla. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 2006;41(9):840–5. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0513-4870.2006.09.008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo Z, Gyulai G, Humphreys M, Horvath L, Bittsanszky A, Lagler R, et al. Genetic variation of melon (C-melo) compared to an extinct landrace from the Middle Ages (Hungary) I. rDNA, SSR and SNP analysis of 47 cultivars. Euphytica. 2005;146(1–2):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-5685-y [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye S, Dhillon S, Ke X, Collins AR, Day INM. An efficient procedure for genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29(17):88–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SB, Xu FR, Zhang YH, Lin J, Song CF, Fang XW. Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of a novel PANICLE AND SPIKELET DEGENERATION gene in rice. Euphytica. 2015;206(3):793–803. doi: 10.1007/s10681-015-1525-x [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou YP, Luo QQ, Chen CJ, Zhou MG. Application of tetra primer ARMS-PCR approach for detection of Fusarium graminearum genotypes with resistance to carbendazim. Australas Plant Path. 2013;42(1):73–8. doi: 10.1007/s13313-012-0162-2 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garces-Claver A, Fellman SM, Gil-Ortega R, Jahn M, Arnedo-Andres MS. Identification, validation and survey of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associated with pungency in Capsicum spp. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2007;115(7):907–16. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0617-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacci M, Miranda VFO, Martins VG, Figueira AVO, Lemos MV, Pereira JO, et al. A search for markers of sugarcane evolution. Genet Mol Biol. 2001;24(1–4):169–74. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572001000100023 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porebski S, Bailey LG, Baum BR. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 1997;15(1):8–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02772108 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Besse P. Nuclear Ribosomal RNA Genes: ITS Region. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1115:141–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-767-9_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medrano RFV, de Oliveira CA. Guidelines for the Tetra-Primer ARMS-PCR Technique Development. Mol Biotechnol. 2014;56(7):599–608. doi: 10.1007/s12033-014-9734-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldwin BG, Sanderson MJ, Porter JM, Wojciechowski MF. The its Region of Nuclear Ribosomal DNA: A Valuable Source of Evidence on Angiosperm Phylogeny. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1995;82(2):247–77. doi: 10.2307/2399880 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Zhang L, Li G, Qin R, Liu H. Application of nrDNA-ITS Sequences in Plant Phylogeny and Evolution. Botanical Research. 2014;3(1):32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sang T, Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF. Documentation of reticulate evolution in peonies using internal transcribed spacer sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA Implications for biogeography and concerted evolution. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 1995;92(15):6813–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters ER, Schaal BA. Biased gene conversion is not occurring among rDNA repeats in the Brassica triangle. Genome. 1996;39(1):150–4. Epub 1996/02/01. doi: 10.1139/g96-020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian J, Sun Y, Duan YH. Internal Transcribed Spacer Region of rDNA in Common Wheat and Its Genome Origins. Acta Agronomica Sinica. 2009;35(6):1021–9. doi: 10.1016/S1875-2780(08)60088-7 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edme SJ, Glynn NG, Comstock JC. Genetic segregation of microsatellite markers in Saccharum officinarum and S. spontaneum. Heredity. 2006;97(5):366–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mary S, Nair NV, Chaturvedi PK, Selvi A. Analysis of genetic diversity among Saccharum spontaneum L. From four geographical regions of India, using molecular markers. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2006;53(6):1221–31. doi: 10.1007/s10722-005-2433-z [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devarumath RM, Kalwade SB, Kawar PG, Sushir KV. Assessment of Genetic Diversity in Sugarcane Germplasm Using ISSR and SSR Markers. Sugar Tech. 2012;14(4):334–44. doi: 10.1007/s12355-012-0168-7 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandra A, Grisham MP, Pan YB. Allelic divergence and cultivar-specific SSR alleles revealed by capillary electrophoresis using fluorescence-labeled SSR markers in sugarcane. Genome. 2014;57(6):363–72. doi: 10.1139/gen-2014-0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blattner FR. TOPO6: a nuclear single-copy gene for plant phylogenetic inference. Plant Systematics & Evolution. 2016;302(2):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00606-015-1259-1 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mccormack JE, Hird SM, Zellmer AJ, Carstens BC, Brumfield RT. Applications of next-generation sequencing to phylogeography and phylogenetics. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2013;66(2):526–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linder HP, Naciri Y. Species delimitation and relationships: The dance of the seven veils. Taxon. 2015;64(1):3–16. doi: 10.12705/641.24 [Google Scholar]

- 35.De SR, Adams KL, Vandepoele K, Van Montagu MC, Maere S, Van d P Y. Convergent gene loss following gene and genome duplications creates single-copy families in flowering plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(8):2898–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300127110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piperidis G, Piperidis N, D’Hont A. Molecular cytogenetic investigation of chromosome composition and transmission in sugarcane. Mol Genet Genomics. 2010;284(1):65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0546-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang P. Chromosome genetic analysis of nobilization of Saccharum spontaneum: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University; 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.