Abstract

The erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma (Eph) receptors are the largest family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) that include two major subclasses, EphA and EphB. They form an important cell communication system with critical and diverse roles in a variety of biological processes during embryonic development. However, dysregulation of the Eph/ephrin interactions is implicated in cancer contributing to tumour growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Here, we focus on EphB4 and review recent developments in elucidating its role in upper aerodigestive malignancies to include lung cancer, head and neck cancer, and mesothelioma. In particular, we summarize information regarding EphB4 structure/function and role in disease pathobiology. We also review the data supporting EphB4 as a potential pharmacological and immunotherapy target and finally, progress in the development of new therapeutic strategies including small molecule inhibitors of its activity is discussed. The emerging picture suggests that EphB4 is a valuable and attractive therapeutic target for upper aerodigestive malignancies.

Keywords: EphB4, Lung cancer, Head and Neck cancer, Mesothelioma, Receptor tyrosine kinase

1. Introduction

The erythropoietin-producing hepatoma (Eph) receptors represent the largest class of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). They are type I transmembrane proteins that interact with their membrane-bound ligands the ephrins and facilitate cell-to-cell contacts resulting in bidirectional intracellular signaling (Pasquale, 2008; Das et al, 2010). Ephrin stimulation causes receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation of the Eph receptor on the juxtamembrane regions and cytoplasmic tails driving the subsequent recruitment of down-stream signaling molecules (Kullander & Klein R, 2002). These include SH2 and SH3 adapter proteins, Src family kinases, PI3K, MAP kinases, small GTPases, guanine nucleotide exchange factors, and phosphatases, each of which contribute to the complex cell repulsion and adhesion pathways that modulate cell shape, motility and attachment (Pasquale, 2005).

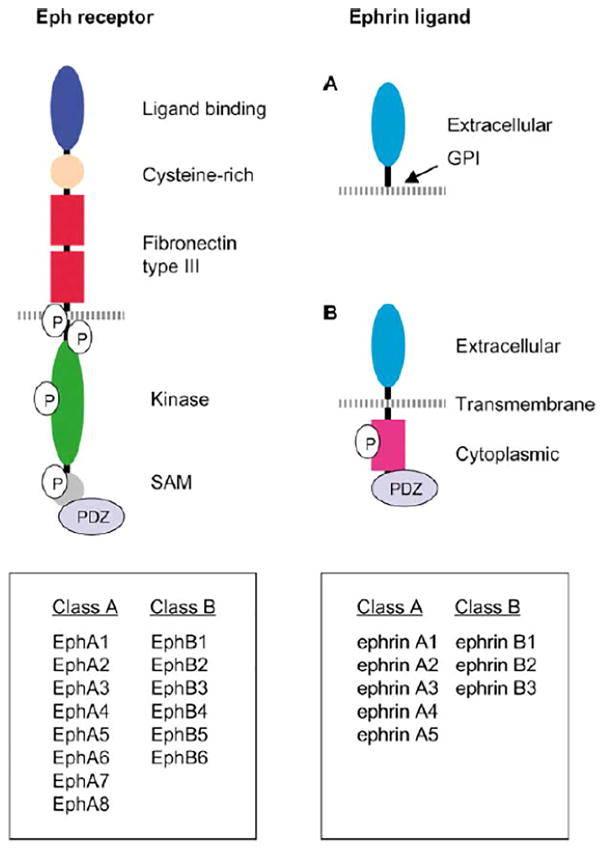

Based on sequence homologies and their binding affinities and characteristics, the Eph receptors are grouped into subclasses namely, Eph A and Eph B receptors, although there is significant redundancy and cross talk between subclasses (Pasquale, 1997; Takemoto et al, 2002; Himanen et al, 2004; Pasquale, 2010). Furthermore, while the members of the ephrin-A subclass (ephrin-A1 to -A5) are tethered to the membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor, the members of the ephrin-B subclass (ephrin-B1 to -B3) are transmembrane proteins and have a highly conserved cytoplasmic domain (Hamada et al, 2003).

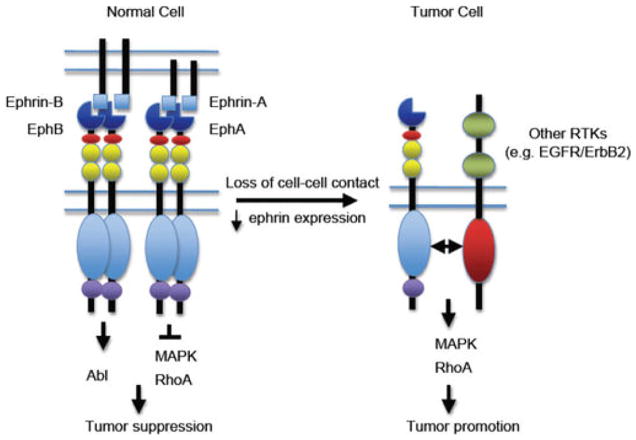

The EphB subfamily, the largest of receptor tyrosine kinases, comprises of six members (EphB1 to 6). Five of them are catalytically competent, while the more divergent EphB6 is catalytically dead (Eph Nomenclature Committee, 1997). Unlike many of the other members in this family that exhibit promiscuity (Pasquale, 2005), the EphB4 receptor has distinctive specificity for a single ligand, ephrinB2; however, EphB4 also binds to ephrinB1 and ephrinB3 albeit weakly (Himanen et al, 2001). Physiologically, EphB4 plays important roles in vascular remodeling of primitive capillary networks into distinct arteries and veins (Wang et al, 1998; Gerety et al, 1999). On the other hand, EphB4 is also known to regulate vascularization in malignant tumours (Kania & Klein, 2016), and is up-regulated in numerous cancer types including upper aerodigestive cancers (reviewed, Pasquale, 2010; Barquilla & Pasquale 2015; Chen et al, 2017). Nonetheless, since Eph-ephrin interactions have been shown to either promote or inhibit tumour growth (Noren & Pasquale, 2007; Pasquale, 2010), the role of these receptors in cancer remains a matter for debate. However, crosstalk between elevated Eph receptors and other oncogenes, such as the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases is thought to result in enhanced cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, presumably independent of ephrin stimulation (reviewed, Vaught et al, 2008) (Fig. 1). Here, we review the function of EphB4, its potential as a therapeutic target, the developments to date on small molecule inhibitors, and EphB4 immunotherapy in upper aerodigestive malignancies.

Fig. 1.

A working model for Eph receptor function in tumor promotion and tumor suppression. In normal cells, engagement of Eph receptors with ephrins on adjacent cells in trans induces receptor forward signaling, leading to inhibition of Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activity, or suppression of Crk activation via Abl kinase activity, and tumor suppression. In tumor cells, disruption of cell-cell junctions inhibits Eph receptor interaction with endogenous ephrins in trans. In addition, Eph receptors are often upregulated whereas ephrins are downregulated. Crosstalk between Eph receptors and other receptor tyrosine kinases such as ErbB2 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) results in increased activity of the Ras-MAPK pathway and the RhoA GTPase, and enhanced tumor malignancy (Vaught et al, 2008).

1.1 The structure of the EphB4 receptor and the EphB4.ephrinB2 complex

EphB4, like all other Eph receptors, is a type I transmembrane protein that has a prototypical RTK topology. Thus, the protein is characterized by an N-terminal multidomain extracellular region, a single transmembrane segment, and a cytoplasmic region that contains the kinase domain in the C-terminus (Lisabeth et al, 2013). The extracellular domain includes a globular ligand-binding domain, a cysteine-rich region, composed of an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like motif, and two fibronectin type III repeats (Himanen et al, 2001). The ephrin-binding domain has a high- affinity binding site that mediates the biochemical communication between EphB4 and the ephrinB2 in adjacent cells. The cytoplasmic region contains a tyrosine kinase domain and protein-protein interacting modules, including a sterile-α-motif (SAM) and a PDZ-binding motif (Pasquale, 2008). The SAM domain is a protein-interacting domain that promotes homo-dimerization and the oligomerization of receptors. The PDZ-binding motif mediates the organization of protein complexes at the plasma membrane (Zisch et al, 2000) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Domain structure and signaling of Eph receptors and ephrin ligands. Both GPI-anchored ephrinA and transmembrane ephrinB ligands interact with the N-terminal globular domain of Eph receptors for ligand binding. The globular domain is followed by a cysteine-rich region and two fibronectin type III repeats, which contain a dimerization motif. Phosphorylated tyrosine residues provide docking sites for SH2 domain-containing signaling proteins. SAM domains form homodimers and may regulate receptor dimerization. Signaling proteins containing PDZ domains dock to the carboxy terminus of Eph receptors and ephrinB ligand. Reproduced with permission from Cheng et al, 2002.

The crystal structures of the EphB4 receptor in complex with the extracellular domain of ephrinB2 complex (Chrencik et al, 2006a) and the EphB4 receptor in complex with antagonistic peptide TNYL-RAW (TNYLFSPNGPIARAW) that binds with high-affinity (15 nM) (Chrencik et al, 2006b) have been solved. The EphB4-ephrinB2 structural analysis suggested that L95 plays a particularly important role in defining ligand selectivity of EphB4. Indeed, all other members of this receptor family that promiscuously bind many ephrins have a conserved R at the position corresponding to L95 of EphB4. Furthermore, amino acid changes in the EphB4 ligand binding cavity when designed based on comparison with the crystal structure of the more promiscuous EphB2 receptor, yielded EphB4 variants with altered binding affinity for ephrinB2 and TNYL-RAW. Finally, binding studies employing isothermal titration calorimetry with the EphB4 L95R mutant confirmed the importance of this amino acid in conferring high affinity binding to both ephrinB2 and TNYL-RAW (Chrencik et al, 2006b).

More recently, Dai et al (2014) by simulating conformational ensembles and recognition energy landscapes starting from separated Eph and ephrin molecules and proceeding up to the formation of receptor-ligand complexes, demonstrated that two pairs of dynamic salt bridges are unique to EphB4, resulting in ephrinB2 recognition and conformational selection. Together these structural biology and computational studies provide tremendous insight on the specificities for the interaction between EphB4 and ephrinB2 and how this knowledge could be applied to drug discovery in designing novel compounds that recapitulate the critical contacts of the peptide and EphB4 with good pharmacokinetic properties.

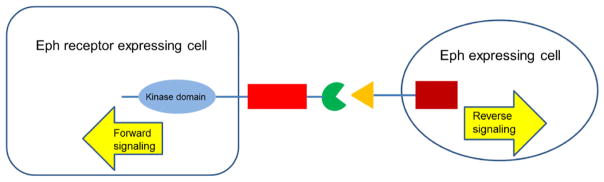

1.2 Forward and reverse signaling

Since the receptor and the ligand typically reside on different cells, a rather unique feature of the Eph/ephrin axis is that the complexes emanate signals bidirectionally. Thus, forward signals that depend on Eph kinase activity propagate in the receptor-expressing cell, and reverse signals that depend on Src family kinases propagate in the ligand (ephrin)-expressing cell (Fig. 3). Eph signalling controls cell morphology, adhesion, migration and invasion by modifying the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and influencing the activities of integrins and intercellular adhesion molecules (Pasquale, 2005; Pasquale, 2008). Additionally, recent work has also uncovered Eph effects on cell proliferation and survival as well as specialized cellular functions such as synaptic plasticity, insulin secretion, bone remodelling and immune function (Pasquale, 2008).

Fig. 3.

Bidirectional signaling through the Ephs and ephrins. Bidirectional signaling may occur between an Eph receptor-expressing cell and an ephrin-expressing cell. Forward signals are propagated into the Eph receptor-expressing cell, and reverse signals are propagated into the ephrin-expressing cell.

With regard to forward signaling by EphB4 in cancer cells, while the receptor is upregulated in many cancers, its response to ephrin is muted and, in some cases, ephrin-dependent Eph forward signaling may even be detrimental to tumour progression. For example, EphB4 receptors that are activated by ephrins acquire the remarkable ability to inhibit oncogenic signaling pathways, including Abl-Crk, PI3K-Akt and HRAS-Erk (Huang et al, 2008). In contrast, some cancer cells are stimulated by activation (Xiao et al, 2012) and in others, overexpression of the active EphB4 enhanced anchorage-independent growth, migration and invasion, all characteristics associated with an aggressive phenotype (Rutkowski et al, 2012) suggesting that the overexpression of EphB4 facilitates tumour progression by forward signaling. However, overexpression of EphB4 or that of an inactive mutant EphB4 kinase in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells promoted cell growth and migration, suggesting EphB4 promoted cell growth and migration independently of its kinase activity and that repressed tumourigenesis (Hu et al, 2014).

Insofar as reverse signaling is concerned, since B ephrins do not possess intrinsic catalytic activity, they rely on the recruitment of signaling molecules such as Src family kinases, which phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues in the intra-cytoplasmic domain of B ephrins, resulting in receptor engagement and clustering (Salvucci & Tosato, 2012). Furthermore, similar to the situation with forward signaling, reverse signaling has also been observed to result in both tumour suppression as well as progression. For example, tumour cells expressing dominant negative EphB4 are incapable of forward signaling, but remain able to stimulate ephrinB2 reverse signaling, that in turn promotes cell invasion and proliferation. The overexpression of EphrinB2 in cultured cancer cells enhances integrin mediated attachment, migration and invasion (Meyer et al, 2005; Nakada et al, 2010). Considered together, these observations on bidirectional signaling suggest that the role of EphB4/ephrinB2 is context-dependent and can vary from one cancer type to the other. Furthermore, mutations dysregulating Eph function likely also play a role in cancer progression.

1.3 Genetic alterations in EphB4 in upper aerodigestive malignancies

Many receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including several members of the Eph family, are frequently altered in lung cancer where they are believed to play important roles (Merlos-Suárez & Batlle, 2008). For example, a mutation in EphA2 (G391R) causes constitutive kinase activation in lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) where it promotes increased cell survival, cell invasion, focal adhesions, and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (Faoro et al, 2010). Three potentially relevant EphB6 mutations were identified in NSCLC patients (3.8%) that included two point mutations and an in-frame deletion mutation (del915-917). Although catalytically inactive, the point mutations in EphB6 lead to instable proteins while the in-frame deletion enhanced migration and accelerated wound healing in vitro. Furthermore, the del915-917 mutation also increased the metastatic capability of NSCLC cells in an in vivo mouse model suggesting that EphB6 mutations promote metastasis in a subset of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (Bulk et al, 2012). Similarly, it has been reported that EphA3 and EphA5 are frequently altered in NSCLC. While mutations in EphA3 appear to have pro-tumourigenic effects thereby transforming tumour suppressor function of the WT protein in the lung (Zhuang et al, 2012), the functional significance of these alterations in EphA5 is unknown (Saintigny et al, 2012).

Comparatively, there is a lot more information on EphB4, particularly in lung cancer. For example, it has been reported that the gene is overexpressed and amplified in several lung cancer subtypes and is necessary for the growth of lung adenocarcinoma xenografts in mice (Ferguson et al, 2013). Several non-synonymous mutations in EphB4 have also been identified, in human tumour tissues and cell lines. Thus, a mutation resulting in an R564K substitution occurring in the intracellular juxtamembrane (JM) domain was detected in one multiple myeloma cell line (Claudio et al, 2007), and an R889W substitution was detected in one gastric carcinoma tissue sample (Greenman et al, 2007). A detailed genetic analysis of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) also identified several mutations in the ephrin receptor family including EphB4 (Rudin et al, 2012).

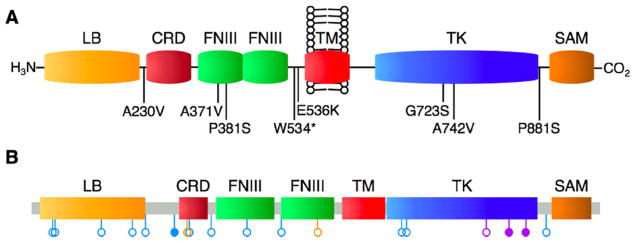

Another comprehensive study by (Ferguson et al, 2015) revealed EphB4 can be mutated in lung cancer and that they lead to putative structural alterations as well as increased cellular proliferation and motility. Notably, the authors detected eight NS EphB4 mutations with one (A230V) in an extracellular linker region, two (A371V and P381S) in the first extracellular fibronectin III repeat, two (W534* and E536K) in the extracellular juxtamembrane domain, two (G723S and A742V) in the tyrosine kinase domain, and one (P881S) in an intracellular linker region just C-terminal to the tyrosine kinase domain. Three of these (A230V, A371V, and P381S) occurred in adenocarcinoma, one (A742V) occurred in SCC, and four (W534*, E536K, G723S, and P881S) occurred in SCLC. Seven of these eight mutations (all except A371V) had not been previously detected (Fig. 4). Overall, the non-synonymous mutations occurred in 7% of samples, with non-synonymous mutation rates of 9% in adenocarcinoma, 9% in SCLC, and 3% in SCC. These observations together with several others (Ding et al, 2008; Imielinski et al, 2012; Mäki-Nevala et al, 2013) provide a panoramic view of the EphB4 mutational landscape in lung cancer. Interestingly, of the 16 sites with EphB4 mutations in adenocarcinoma tissues identified by Ferguson et al (2015), 12.5% were located in the kinase domain underscoring the functional implications. Furthermore, a bioinformatics analysis of these mutations revealed that a) they are mutually exclusive from other common RTK variants in lung cancer, b) they correspond to analogous sites of other RTK’s variations in cancers, c) they are predicted to be oncogenic based on biochemical, evolutionary, and domain-function constraints, and d) EPHB4 mutations can induce broad changes in the kinome signature of lung cancer cells (Ferguson et al, 2015). Taken together, these data illuminate the role of EphB4 in lung cancer and further identify EphB4 as a potentially important therapeutic target. However, thus far, no non-synonymous EphB4 mutations have been reported in HNSCC or pleural mesothelioma tissues.

Fig. 4.

EPHB4 mutations detected in human lung cancer tissues. A schematic of non-synonymous mutation sites within the domain structure of EPHB4 is shown. A: EPHB4 mutations reported in the present study. B: Compiled EPHB4 mutations across all lung cancer datasets currently included in cBioPortal. Blue, adenocarcinoma; purple, squamous cell carcinoma; orange, small cell lung carcinoma. Open circles, nonsynonymous point mutations; closed circles, splice site variant or nonsense mutation. Reproduced with permission from Ferguson et al, 2015.

2. EphB4 as a therapeutic target in aerodigestive cancers

2.1 Lung cancer

Ferguson et al (2013) demonstrated that EphB4 is overexpressed 3-fold in lung tumours compared to paired normal tissues and frequently exhibits gene copy number increases in lung cancer. The authors also showed that overexpression of EphB4 promotes cellular proliferation, colony formation, and motility, while EphB4 inhibition reduces cellular viability in vitro, halts the growth of established tumours in mouse xenograft models when used as a single target strategy, and causes near complete regression of established tumours when used in combination with paclitaxel.

Zheng et al (2012) assessed a single-nucleotide polymorphism in EphB4 to determine its effect on protein expression in NSCLC. The authors found that EphB4 was expressed in 53.6% of patients with cancer but expression in normal samples. Furthermore, EphB4 expression was correlated with differentiation, lymph node metastasis and TNM stage of tumours (P<0.05). Additionally, the polymorphism in EphB4 at rs314310 appeared to correspond to protein expression and disease susceptibility. While the frequencies of CC, CA and AA genotypes were not different between lung cancer patients and healthy controls, the frequencies of C and A alleles were significantly different between these groups (P<0.05). Further analysis showed that the positive rate of EphB4 expression in patients with the AA genotype was significantly higher compared to that in patients with other genotypes (P<0.05). Thus, overexpression of EphB4 plays a role in the occurrence and development of NSCLC and the polymorphism at rs314310 may predispose individuals to this disease (Zheng et al, 2012).

2.2 Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

Masood et al (2006) evaluated the role of EphB4 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). They tested the effect of EphB4-specific siRNA and antisense oligonucleotides (AS-ODN) on cell growth, migration and invasion, and the effect of EphB4 AS-ODN on tumour growth in vivo. The authors found that all HNSCC tumour samples express EphB4 and levels of expression correlate directly with higher stage and lymph node metastasis. Further, 86% HNSCC cell lines express EphB4, which is induced either by EGFR activation or by EPHB4 gene amplification. The ligand, EphrinB2, was expressed in 65% tumours and 71% cell lines tested. Furthermore, EphB4 siRNA and AS-ODN significantly inhibited tumour cell viability, induced apoptosis, activated caspase-8, and sensitized cells to TRAIL-induced cell death. Furthermore, EphB4-specific AS-ODN significantly inhibited the growth of HNSCC tumour xenografts in vivo (Masood et al, 2006).

In a study on six men with HNSCC that had metastasized to the cervical lymph nodes (Sinha et al, 2003), the authors determined if EphB4 is aberrantly expressed in cases of HNSCC and to determine if there is a qualitative difference between the expression of EphB4 on primary and metastatic tumours and its expression on normal mucosa adjacent to primary tumours. From each patient, specimens of the primary tumour, the nodal metastasis, and the adjacent normal mucosa were obtained and analyzed by immunocytochemistry. EphB4 expression was observed in all primary and metastatic tumours but no expression was seen in normal tissue. In each of the six patients, expression was greater in the metastatic tumour than in the primary tumour.

Sinha et al (2006) examined the expression of EphB4 in tumour tissue, surrounding normal tissue, and metastatic lymph node in patients with head and HNSCC and to evaluate its association with disease stage and smoking. Forty-eight patients with different stages of HNSCC (I–IV) were enrolled into this study. Staging was based on the staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. EphB4 expression in tumour tissue, surrounding normal tissue, and metastatic lymph node was evaluated by immunohistochemical analysis, western blot, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). EphB4 expression was then compared between patients based on disease stage and smoking status. The data revealed that EphB4 expression was detected in all tumour specimens and metastatic lymph nodes of patients with HNSCC, but expression levels were higher in the metastatic lymph nodes. There was a statistically significantly higher mean EphB4 protein expression and EphB4 gene amplification in patients with advanced disease (stage III or IV) versus patients with initial disease (stage I or II) and in smokers versus nonsmokers. Thus, overexpression of EphB4 appeared to be associated with advanced stages of HNSCC as well as with patients who smoke. (Sinha et al, 2006).

In yet another study on 50 patients comprising 8 patients with early-stage (stages I and II) and 42 patients with advanced-stage (stages III and IV) HNSCC, EphB4 was upregulated in tumour samples compared to normal (Yavrouian et al, 2008). Furthermore, EphB4 overexpression is associated with poor overall survival in patients with HNSCC. More recently, Ferguson et al (2014) conducted an immunohistochemical analysis of EphB4 expression and progression in HNSCC from dysplasia to cancer. The authors also found that the tumour expression of EphB4 in HNSCC increased with disease stage (in primary tumour tissues and nodal metastases) consistent with those reported earlier by Sinha et al. (2006) and by Yavrouian et al. (2008) which demonstrated that increased EphB4 expression is correlated with shorter survival.

2.3 Malignant mesothelioma

Mesothelioma is a rare malignancy that is incurable and patients typically have a short survival despite surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) often develops decades following exposure to asbestos. Current best therapy produces a response in only half of patients, and the median survival with this therapy is usually less than a year. Several studies have identified EphB4-Ephrin-B2 as potential target in MPM.

For example, Xia et al (2005) evaluated the expression and functional significance of EphB4 in vitro and in a murine model of MM. The protein was highly expressed in MM cell lines and primary tumour tissues but not in normal mesothelium. Knocking down EphB4 in MM cell lines showed reduction in cell survival, migration, and invasion. Knocking down EphB4 initiated caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and down-regulation of the anti-apoptotic protein bcl-xl. EphB4 knockdown also resulted in reduced phosphorylation of Akt and down-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 transcription. In addition, murine tumour xenograft studies showed a marked reduction in tumour growth that was accompanied by a decline in EphB4 protein expression, reduced cell division, apoptosis in tumour tissue, and decreased microvascular density upon EphB4 silencing (Xia et al, 2005).

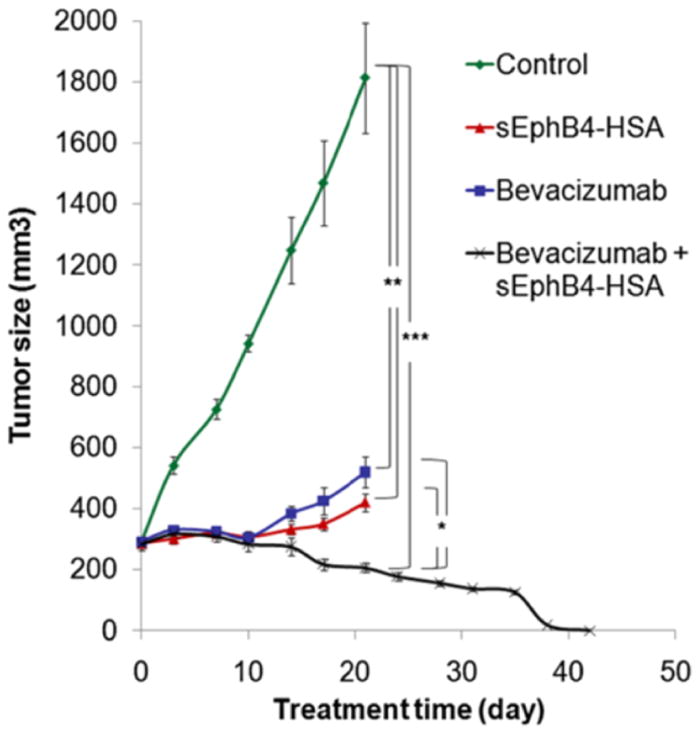

More recently, Liu et al (2013) who investigated EphB4 expression in surgical samples of human mesothelioma tissues by immunohistochemistry found that EphB4 was overexpressed in 72% of the specimens evaluated with 85% representing epithelioid and 38% that of sarcomatoid subtypes. The authors also treated mice carrying mesothelioma xenograft tumours with an EphB4 inhibitor namely, monomeric soluble EphB4 fused to human serum albumin (sEphB4-HAS) or a combination of sEphB4-HSA and a biologic agent, anti-VEGF antibody (Bevacizumab). The EphB4 inhibitor sEphB4-HSA was highly active as a single agent to inhibit tumour growth (Fig. 5), accompanied by tumour cell apoptosis as well as inhibition of PI3K and Src signaling. Furthermore, the combination therapy was superior to either agent alone and led to complete tumour regression. Considered together the data suggest that EphB4 is a promising therapeutic target in MM.

Fig. 5.

In vivo efficacy of sEphB4-HSA combined with Bevacizumab. 211H tumors were treated with sEphB4-HSA alone (20 mg/kg, 3 times a week), Bevacizumab alone (20 mg/kg, 3 times a week), or sEphB4-HSA combined with Bevacizumab. PBS was used as control. Treatment in single-agent groups and control group was continued for 21 days, whereas treatment in the combination group was continued for 42 days until complete tumor regression. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.02; ***, P<0.01. Error bars indicate standard error of mean. Reproduced with permission from Liu et al, 2013.

3. Pharmacologically targeting EphB4

3.1 Kinase inhibitors

Numerous small molecule compounds and their derivatives that bind the ATPase domain and other molecules including proteins and antibodies that target receptor interaction other than the kinase domain have been reported. For excellent reviews that provide a comprehensive report of the various compounds, from discovery to validation, mode of action, and the indications that they are being evaluated both at the preclinical and clinical testing stages, the reader is referred to Boyd et al (2014), Unzue et al (2016) and Chen et al (2017). While these reviews provide extensive updates on these compounds as well as several immunotherapy approaches (see below) for a variety of indications in which the Eph/ephrin, particularly EphB4/ephrinB2 is activated, there is no little information with regard to the latter in upper aerodigestive malignancies. A brief overview of these molecules targeting EphB4 is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

EphB4 targeting molecules.

| Molecule | Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase inhibitors | ||

| Anilinopyrimidine derivatives | ATP competitors | Bardelle et al 2008a; 2008b |

| Benzenesulfonamide derivative | ATP competitor | Miyazaki, et al, 2007 |

| XL647 (also known as EXEL-7647) | ATP competitor | Gendreau et al 2007 |

| Bis-anilino-pyrimidine derivatives | ATP competitor | Barlaam et al, 2011 |

| Xanthine derivatives | ATP competitor | Lafleur, et al, 2009; Lafleur et al, 2013 |

| Multiple structures | ATP competitors |

Kolb et al, 2008 Unzue et al, 2016 |

| Inhibitors of Eph expression | ||

| Oligonucleotides | Downregulation | Xia et al, 2005; Xia et, 2006; Kumar et al, 2006; Masood et al 2006 |

| Inhibitors of Eph–ephrin interactions | ||

| TNYL-RAW peptide | Ephrin competitor | Koolpe et al, 2005; Chrencik et al, 2006a; |

| APY-d2-4 | Ephrin competitor | Olson et al, 2016 |

| Small linear peptides (MW 600–700 Da) | Ephrin competitor | Duggineni et al, 2012 |

| Soluble EphB4 fused to human serum Albumin (sEphB4-HAS) | EphB4 inhibitor | Liu et al, 2013 |

| Monoclonal antibodies | ||

| mAb 131, mAb 147 | EphB4 inhibitor | Krasnoperov et al, 2010 |

Perhaps, a notable exception may be Tesevatinib (also known as XL647 or KD019), an oral small-molecule inhibitor of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, including endothelial growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, HER2, and EphB4 in NSCLC. This inhibitor was tested in an open-label, multi-institutional Phase II trial to investigate efficacy and safety of XL647 in treatment-naive non–small-cell lung cancer patients clinically enriched for the presence of EGFR mutations (Pietanza et al, 2012) and is currently in a Phase III trial (XL647 versus erlotinib), in patients with stage IIIB–IV NSCLC with progression after first- or second-line chemotherapy (Boyd et al, 2014).

3.2 Molecules that do not target the kinase domain

3.2.1 Peptidomimetics disrupting Eph/ephrin interaction

The extracellular ephrin-binding pocket comprises a broad and shallow groove surrounded by several flexible loops, which makes peptides particularly suitable to target it with high affinity and selectivity. Accordingly, a number of peptides that bind to this domain with micromolar affinity have been identified mainly using phage display (Koolpe et al, 2005) and other approaches. These peptides are generally antagonists that attenuate or inhibit ligand binding and signaling. However, some also act as agonists that mimic ephrin-induced Eph receptor activation (Dines & Lamprecht, 2014).

Previously, most identified antagonistic peptides were linear. But more recently, in light of the potential optimization towards drug leads, cyclic scaffolds are in much favour. Indeed, to date, these efforts and improvements have yielded derivatives with low nanomolar binding affinity, high resistance to plasma proteases and/or long in vivo half-life, underscoring virtues of this targeting approach (Han et al, 2013; Lamberto et al, 2014; Riedl & Pasquale, 2015; Olson et al, 2016).

Thus, using phage display technology, Pasquale and coworkers (Koople et al, 2005) identified a high-affinity antagonistic peptide named TNYL-RAW that selectively targets EphB4. This peptide is 15 amino acids long, has a molecular weight of ~1700 Da and binds to the ephrin-binding pocket of EphB4 with an affinity comparable with that of the ligand. Subsequently, the same group identified the cyclic peptide APY-d2 (APYCVYRβASWSC-NH2, containing a disulfide bond) as a potent and selective EphA4 antagonist. In addition, the authors found that among several improved APY-d2 derivatives, the cyclic peptides APY-d3 (βAPYCVYRβASWSC-nh2) and APY-d4 (βAPYCVYRβAEWEC-nh2) combine high stability in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid with slightly enhanced potency (Olson et al, 2016).

The same group also reported the structure-based design and chemical synthesis of two novel small molecules of ~600–700 Da which were designed starting from the small and functionally critical C-terminal portion of the TNYL-RAW peptide. These compounds inhibit ephrin-B2 binding to EphB4 at low micromolar concentrations. However, although the ephrin-B2 ligand can interact with multiple other Eph receptors besides EphB4, these two compounds retained the high selectivity of the TNYL-RAW peptide in targeting EphB4. TNYL-RAW peptide displacement experiments using the more potent of the two compounds, compound 5, suggest a competitive mode of inhibition (Duggineni et al, 2013). Altogether, these studies suggest that i) EphB4 antagonistic compounds can serve as promising templates for the further development of small molecule drugs targeting EphB4, and ii) targeting receptor regions other than the kinase domain, may be a viable approach.

3.3.2 Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are particularly well suited as therapeutic agents. They recognize cell surface antigens expressed on target cells and mediate their function through various mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, complement-dependent cytotoxicity, or immune system modulation. Furthermore, the efficacy of mAb therapy can be improved when the mAbs are conjugated to highly potent payloads such as cytotoxic drugs and radiolabeled isotopes. Thus, the use mAbs, and molecules derived from them, have achieved considerable attention and success in recent years establishing this mode of therapy as an important therapeutic strategy in many cancers. Among the upper aerodigestive malignancies, mAbs against EphB4 in particular have been explored in HNSCC as therapeutic agents.

Krasnoperov et al (2010) described two anti EphB4 humanized monoclonal antibodies MAb131 and MAb47 that inhibit tumour angiogenesis and tumour growth by two distinct pathways in a HNSCC cell line among other solid tumours the authors tested in a preclinical setting. The authors found that MAb131 binds to fibronectin-like domain 1 and induces degradation of human EphB4, but not murine EphB4. MAb131 inhibits human endothelial tube formation in vitro and growth of human tumours expressing EphB4 in vivo. In contrast, MAb47 targets fibronectin-like domain 2 of both human and murine EphB4 and does not alter EphB4 receptor levels, but inhibits angiogenesis and growth of both EphB4-positive and EphB4-negative tumours in a mouse HNSCC xenograft model. Furthermore, a combination of MAb47 and another anti-angiogenesis mAb, bevacizumab, enhances the antitumour activity and induces tumour regression (Krasnoperov et al, 2010).

3.3.3 Soluble EphB4 and combination therapy

Aside from the conventional small molecule drug discovery approach, the dire need for effective therapies for upper aerodigestive malignancies has triggered many bold and unconventional approaches. For example, since the receptor and ligand on adjacent cells undergo dimerization and clustering, which are required for Eph/ephrin activation and signaling, Kertesz et al (2006) tested the possibility that the soluble extracellular domain of EphB4 (sEphB4) would not itself activate EphrinB2 and also block phosphorylation of EphB4 and EphrinB2 on cells when stimulated by clustered EphrinB2 or EphB4, respectively.

sEphB4 is a soluble decoy of EphB4 that blocks EphB4-Ephrin-B2 bi-directional signaling. sEphB4-HSA has full-length human serum albumin fused to the C-terminus of sEphB4 to improve half-life and delivery (Shi et al, 2012), and both variants of the protein, sEphB4 alone and sEphB4-HAS, have anti-tumour activities in multiple tumour models (Scehnet et al, 2009; Djokovic et al, 2010). The authors found that the soluble monomeric derivative of the extracellular domain of EphB4 (sEphB4) blocks activation of EphB4 and EphrinB2, suppresses endothelial cell migration, adhesion and tube formation in vitro, and inhibits the angiogenic effects of various growth factors (VEGF and bFGF) in vivo (Shi et al, 2012). Furthermore, sEphB4 also inhibited tumour growth in murine tumour xenograft models of MM suggesting that sEphB4 may be a potential therapeutic candidate for MM.

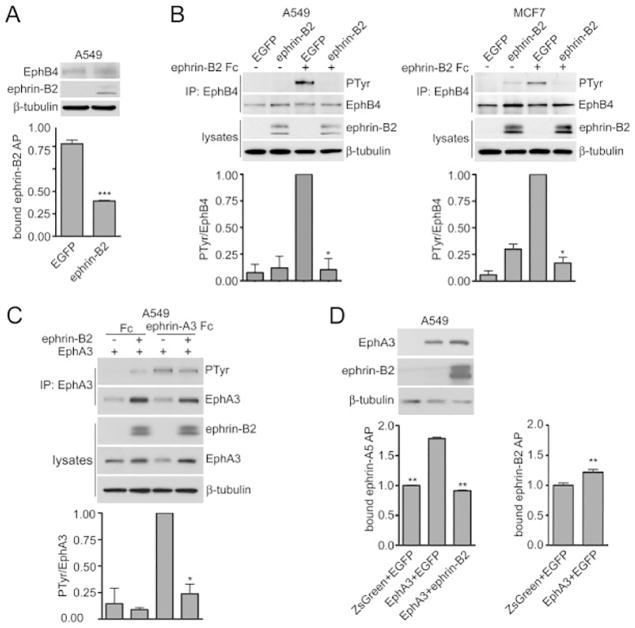

3.3.4 Attenuation of Eph receptor activity by ‘cis’ interaction

Falivelli et al (2013) have explored yet another novel mechanism for the Eph/ephrin axis that could potentially be exploited therapeutically. Although it was tacitly assumed that Eph receptor activation and signaling is mediated by interacting with ephrin “in trans”, studies in the nervous system revealed that Eph receptors and ephrins are not only coexpressed in the same cell but can also engage in lateral “cis” associations (Kao & Kania, 2011), albeit by binding to a different region (Carvalho et al, 2006). These interactions attenuate receptor activation by ephrins in trans with critical functional consequences. To test the possibility in cancer cells, Falivelli et al (2013) introduced the proteins into lung cancer cells using lentiviruses. The authors found that when coexpressed, ephrin-A3 can inhibit the ability of EphA2 and EphA3 to bind ephrins in trans and become activated, while ephrin-B2 can inhibit not only EphB4 but also EphA3. The cis inhibition of EphA3 by ephrin-B2 implies that in some cases ephrins that cannot activate a particular Eph receptor in trans can nevertheless inhibit its signaling ability through cis association (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Coexpressed ephrin-B2 attenuates EphB4 as well as EphA3 activation in cancer cells. (A) The histogram shows the binding of ephrin-B2 AP to A549 cells infected with lentiviruses encoding EGFP-ephrin-B2 or EGFP, revealing that ephrin-B2 coexpression inhibits ephrin-B2 AP binding to EphB4. Normalized means from 3 experiments (each with triplicate samples) ± SE are shown. ***p<0.001 by unpaired t test for the comparison of cells expressing ephrin-B2 with cells not expressing ephrin-B2. The immunoblot of the cell lysates shows expression of EphB4, ephrin-B2 and β-tubulin as loading control. (B) A549 lung cancer cells and MCF7 breast cancer cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding EGFP-ephrin-B2 or EGFP. EphB4 immunoprecipitates were probed by immunoblotting for phosphotyrosine (PTyr) and reprobed for EphB4. Cell lysates were probed for ephrin-B2 with an anti-EGFP antibody and for β-tubulin as loading control. The histograms show normalized means ± SE quantified from 2 immunoblots for each cell line. *p<0.05 by one sample t test for the comparison of ephrin-B2 Fc-treated cells expressing ephrin-B2 with cells not expressing ephrin-B2. (C) A549 cells were infected with a lentivirus encoding EphA3 and ZsGreen together with a lentivirus encoding EGFP-ephrin-B2 or EGFP only. Control cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding ZsGreen and EGFP. EphA3 immunoprecipitates were probed by immunoblotting for phosphotyrosine (PTyr) and reprobed for EphA3. Lysates were probed for ephrin-B2 with an anti-EGFP antibody as well as for EphA3 and for β-tubulin as loading control. The histogram shows normalized means ± SE quantified from 2 immunoblots. *p<0.05 by one sample t test for the comparison of ephrin-A3 Fc-treated cells expressing ephrin-B2 with cells not expressing ephrin-B2. (D) Ephrin-A5 AP binding to cell surface EphA3 is inhibited by ephrin-B2 coexpression. The histogram shows means ± SE from 3 experiments (each with triplicate samples) for the binding of ephrin-A5 AP or ephrin-B2 AP to the A549 cells used for the experiment in C. For ephrin-A5 binding, **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc test for the comparison with cells expressing EphA3 and EGFP; for ephrin-B2 AP binding, **p<0.01 by unpaired t test for the comparison of cells expressing or not expressing EphA3. The immunoblot of the cell lysates shows expression of ephrin-B2, EphA3 and β-tubulin as loading control, verifying that ephrin-B2 coexpression did not reduce EphA3 levels. From, Falivelli et al (2013).

Consistent with this argument, Tang et al (1999) who surveyed the expression of transcripts encoding the various EphB receptors and the ephrin-B ligands in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) observed that transcripts encoding multiple members of the EphB subgroup and the ephrin-B subgroup are coexpressed in SCLC cell lines and tumours. These results suggest that the EphB subgroup receptor kinases may modulate the biological behavior of SCLC through autocrine and/or juxtacrine activation by ephrin-B ligands that are expressed in the same or neighboring cells. Interestingly, a mutation in EphA3 identified in lung cancer enhances cis interaction with ephrin-A3. Taken together, these tantalizing observations suggest that modulating Eph receptor, more specifically EphB4 activity in cis may be a novel therapeutic approach for upper aerodigestive malignancies.

3.3.5 Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy and combinatorial therapy

In addition to the therapeutic strategies discussed above, T-cell-based immunotherapy approaches have gained considerable momentum in treating various cancers including upper aerodigestive malignancies, particularly lung cancer and MM in recent years. One such approach being investigated is administration of tumour antigen-targeted T cells with transduction of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). CARs are synthetic receptors that target T cells to cell-surface antigens and augment T-cell function and persistence. CAR T-cell therapy consists of a fusion protein genetically engineered to express the binding domain from the single-chain variable fragment of an antibody grafted onto a T-cell and functions by targeting tumour-associated antigens (reviewed, Yong et al, 2017).

In MM, this approach has targeted several antigens including tumour-associated antigens (e.g., carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA], disialoganglioside; glypican-3, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2], mesothelin [MSLN], PD-1, and receptor tyrosine-kinase-like orphan receptor), novel gene products that arise from splice variants (EGFR) and abnormal glycosylation (mucin 1 [MUC1]), and stromal elements associated with the tumour microenvironment (fibroblast activation protein [FAP] and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (reviewed, Zeltsman et al, 2017). Similarly, Li et al (2016) explored the antitumour potential of third-generation glypican 3 (GPC3)-redirected CAR-engineered T lymphocytes (CARgpc3 T cells) in tumour models of lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). In the presence of GPC3-positive SCC cells, CARgpc3 T cells were highly activated and increased in number. CARgpc3 T cells could specifically lyse GPC3-positive SCC cells in vitro. In two established SCC xenograft models, CARgpc3 T cells almost completely eliminated the growth of GPC3-positive cells. Additionally, the CARgpc3 T cells were able to persist in vivo and efficiently infiltrate the cancerous tissues. Taken together, these findings indicate that CARgpc3 T cells might be a novel potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of patients with SCC (Li et al, 2016).

Another interesting approach that combines different therapies targets immune check point inhibition together with CAR-T. Since the expression of PD-L1/2, ligands that bind with the receptor PD1, in solid tumours inhibits CAR T-cell efficacy, a PD-1 dominant negative receptor expressed in CAR T-cells provides cell-intrinsic checkpoint blockade and augments antitumour efficacy. Thus, a combinatorial immunotherapeutic strategy of combining CAR T-cells with checkpoint blockade appears a promising treatment approach for solid tumours (Chen et al, 2016). However, while these studies along with several others (Morello et al, 2016) highlight the potential for CAR-T therapy, to date there is no report using EphB4 or ephrin2.

4. Biomarker potential

Comparatively speaking, very little is known about the potential of EphB4 as a biomarker, especially in upper aerodigestive malignancies. A recent study by Yu et al (2016) who evaluated cell-free RNA content in the peripheral blood as a potential biomarker for detecting CTCs in NSCLC patients, found that the expression of EphB4 in PBMCs correlated with histopathological type. A survival analysis showed that the patients with enhanced expression of EphB4 along 3 other mRNAs in PBMCs had poorer disease-free survival and overall survival than those without (all p < 0.0001) suggesting that alteration of cell-free RNA content in peripheral blood might have clinical ramifications in the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC patients (PMID:27827952). Similarly, Yavrouian et al (2008) examined the expression of EphB4 and EphrinB2 in tumor tissue and surrounding normal tissue in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) to evaluate its association with overall patient survival. Overall survival in patients was then compared with EphB4 and EphrinB2 expression. The authors found that EphB4 overexpression was greater than that of EphrinB2 compared with normal tissue. There was a statistically significant decrease in overall survival among patients with elevated EphB4 and EphrinB2 expression (P < .001) suggesting that EphB4 and EphrinB2 overexpression is associated with poor overall survival in patients with HNSCC (PMID:18794445).

5. Concluding remarks

Notwithstanding the fact that both forward and reverse signaling by the EphB4/ephrinB2 interaction is context-dependent and can vary from one cancer type to another, the data reviewed here underscore the oncogenic, rather than tumour suppressor, role for EphB4 in upper aerodigestive malignancies including lung cancer, HNSCC and MM. Consistent with its oncogenic potential in these cancers, several small molecule inhibitors that inhibit the kinase activity, immunotherapy strategies, and other novel approaches such as soluble receptor and CAR-T therapy are being aggressively pursued some of which have shown promising results in clinical studies. Finally, data form studies investigating the effects of combinatorial treatments that target EphB4 with other RTKs dysregulated in upper aerodigestive malignancies look quite promising.

Despite the optimism, an important step going forward will involve understanding the EphB4- ephrinB2 activities beyond bidirectional signaling, particularly the interactions in ‘cis’, and elucidating the crosstalk with oncogenic pathways in light of the success with combinatorial therapy. Finally, systematic studies are needed to address the role of EphB4-mediated signaling influences metastasis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and drug resistance in upper aerodigestive malignancies. Finally, although preliminary studies with small patient cohorts raise the possibility of EphB4 as a potential biomarker for prognosis, additional studies will be required to fully evaluate this possibility.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA033572 (RS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das A, Shergill U, Thakur L, Sinha S, Urrutia R, Mukhopadhyay D, Shah VH. Ephrin B2/EphB4 pathway in hepatic stellate cells stimulates Erk-dependent VEGF production and sinusoidal endothelial cell recruitment. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G908–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00510.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:462–475. doi: 10.1038/nrm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquale EB. The Eph family of receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takemoto M, Fukuda T, Sonoda R, Murakami F, Tanaka H, Yamamoto N. Ephrin-B3-EphA4 interactions regulate the growth of specific thalamocortical axon populations in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1168–1172. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himanen JP, Chumley MJ, Lackmann M, Li C, Barton WA, Jeffrey PD, Vearing C, Geleick D, Feldheim DA, Boyd AW, Henkemeyer M, Nikolov DB. Repelling class discrimination: ephrin-A5 binds to and activates EphB2 receptor signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:501–509. doi: 10.1038/nn1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:165–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamada K, Oike Y, Ito Y, Maekawa H, Miyata K, Shimomura T, Suda T. Distinct roles of ephrin-B2 forward and EphB4 reverse signaling in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:190–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000055440.89758.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unified nomenclature for Eph family receptors and their ligands, the ephrins. Eph Nomenclature Committee. Cell. 1997;90:403–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himanen JP, Rajashankar KR, Lackmann M, Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M, Nikolov DB. Crystal structure of an Eph receptor-ephrin complex. Nature. 2001;414:933–938. doi: 10.1038/414933a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang UH, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerety SS, Wang UH, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Symmetrical mutant phenotypes of the receptor EphB4 and its specific transmembrane ligand ephrin-B2 in cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kania A, Klein R. Mechanisms of ephrin-Eph signalling in development, physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:240–256. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barquilla A, Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins: therapeutic opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Zhang H, Zhang Y. Targeting receptor tyrosine kinase EphB4 in cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol S1044–. 2017;579:30162–1. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noren NK, Pasquale EB. Paradoxes of the EphB4 receptor in cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3994–3997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaught D, Brantley-Sieders DM, Chen J. Eph receptors in breast cancer: roles in tumor promotion and tumor suppression. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:217. doi: 10.1186/bcr2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lisabeth EM, Falivelli G, Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signaling and ephrins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zisch AH, Pazzagli C, Freeman AL, Schneller M, Hadman M, Smith JW, Ruoslahti E, Pasquale EB. Replacing two conserved tyrosines of the EphB2 receptor with glutamic acid prevents binding of SH2 domains without abrogating kinase activity and biological responses. Oncogene. 2000;19:177–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chrencik JE, Brooun A, Recht MI, Kraus ML, Koolpe M, Kolatkar AR, Bruce RH, Martiny-Baron G, Widmer H, Pasquale EB, Kuhn P. Structure and thermodynamic characterization of the EphB4/ephrin-B2 antagonist peptide complex reveals the determinants for receptor specificity. Structure. 2006a;14:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chrencik JE, Brooun A, Kraus ML, Recht MI, Kolatkar AR, Han GW, Seifert JM, Widmer H, Auer M, Kuhn P. Structural and biophysical characterization of the EphB4-ephrinB2 protein-protein interaction and receptor specificity. J Biol Chem. 2006b;281:28185–28192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai D, Huang Q, Nussinov R, Ma B. Promiscuous and specific recognition among ephrins and Eph receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1844:1729–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang X, Wu D, Jin H, Stupack D, Wang JY. Induction of cell retraction by the combined actions of Abl-CrkII and Rho-ROCK1 signaling. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:711–723. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao Z, Carrasco RA, Kinneer K, Sabol D, Jallal B, Coats S, Tice DA. EphB4 promotes or suppresses Ras/MEK/ERK pathway in a context-dependent manner implications for EphB4 as a cancer target. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:630–637. doi: 10.4161/cbt.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutkowski R, Mertens-Walker I, Lisle JE, Herington AC, Stephenson SA. Evidence for a dual function of EphB4 as tumour promoter and suppressor regulated by the absence or presence of the ephrin-B2 ligand. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E614–24. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu FQ, Tao Z, Shen ZY, Wang XL, Hua F. Down-regulation of EphB4 phosphorylation is necessary for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma tumourigenecity. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:7225–7232. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salvucci O, Tosato G. Essential roles of EphB receptors and EphrinB ligands in endothelial cell function and angiogenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2012;114:21–57. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386503-8.00002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer S, Hafner C, Guba M, Flegel S, Geissler EK, Becker B, et al. Ephrin-B2 overexpression enhances integrin-mediated ECM-attachment and migration of B16 melanoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1197–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakada M, Anderson EM, Demuth T, Nakada S, Reavie LB, Drake KL, Hoelzinger DB, Berens ME. The phosphorylation of ephrin-B2 ligand promotes glioma cell migration and invasion. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1155–1165. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merlos-Suárez A, Batlle E. Eph-ephrin signalling in adult tissues and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faoro L, Singleton PA, Cervantes GM, Lennon FE, Choong NW, Kanteti R, Ferguson BD, Husain AN, Tretiakova MS, Ramnath N, Vokes EE, Salgia R. EphA2 mutation in lung squamous cell carcinoma promotes increased cell survival, cell invasion, focal adhesions, and mammalian target of rapamycin activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18575–18585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulk E, Yu J, Hascher A, Koschmieder S, Wiewrodt R, Krug U, Timmermann B, Marra A, Hillejan L, Wiebe K, Berdel WE, Schwab A, Müller-Tidow C. Mutations of the EPHB6 receptor tyrosine kinase induce a pro-metastatic phenotype in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhuang G, Song W, Amato K, Hwang Y, Lee K, Boothby M, Ye F, Guo Y, Shyr Y, Lin L, Carbone DP, Brantley-Sieders DM, Chen J. Effects of cancer-associated EPHA3 mutations on lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1183–1198. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saintigny P, Peng S, Zhang L, Sen B, Wistuba II, Lippman SM, Girard L, Minna JD, Heymach JV, Johnson FM. Global evaluation of Eph receptors and ephrins in lung adenocarcinomas identifies EphA4 as an inhibitor of cell migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2021–2032. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferguson BD, Liu R, Rolle CE, Tan YH, Krasnoperov V, Kanteti R, Tretiakova MS, Cervantes GM, Hasina R, Hseu RD, Iafrate AJ, Karrison T, Ferguson MK, Husain AN, Faoro L, Vokes EE, Gill PS, Salgia R. The EphB4 receptor tyrosine kinase promotes lung cancer growth: a potential novel therapeutic target. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claudio JO, Zhan F, Zhuang L, Khaja R, Zhu YX, Sivananthan K, Trudel S, Masih-Khan E, Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Scherer SW, Shaughnessy J, Stewart AK. Expression and mutation status of candidate kinases in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1124–1127. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, Edkins S, O’Meara S, Vastrik I, Schmidt EE, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Bhamra G, Buck G, Choudhury B, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Perry J, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Tofts C, Varian J, Webb T, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Cahill DP, Louis DN, Goldstraw P, Nicholson AG, Brasseur F, Looijenga L, Weber BL, Chiew YE, DeFazio A, Greaves MF, Green AR, Campbell P, Birney E, Easton DF, Chenevix-Trench G, Tan MH, Khoo SK, Teh BT, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Wooster R, Futreal PA, Stratton MR. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferguson BD, Tan YH, Kanteti RS, Liu R, Gayed MJ, Vokes EE, Ferguson MK, Iafrate AJ, Gill PS, Salgia R. Novel EPHB4 receptor tyrosine kinase mutations and kinomic pathway analysis in lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10641. doi: 10.1038/srep10641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, Fulton L, Fulton RS, Zhang Q, Wendl MC, Lawrence MS, Larson DE, Chen K, Dooling DJ, Sabo A, Hawes AC, Shen H, Jhangiani SN, Lewis LR, Hall O, Zhu Y, Mathew T, Ren Y, Yao J, Scherer SE, Clerc K, Metcalf GA, Ng B, Milosavljevic A, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Osborne JR, Meyer R, Shi X, Tang Y, Koboldt DC, Lin L, Abbott R, Miner TL, Pohl C, Fewell G, Haipek C, Schmidt H, Dunford-Shore BH, Kraja A, Crosby SD, Sawyer CS, Vickery T, Sander S, Robinson J, Winckler W, Baldwin J, Chirieac LR, Dutt A, Fennell T, Hanna M, Johnson BE, Onofrio RC, Thomas RK, Tonon G, Weir BA, Zhao X, Ziaugra L, Zody MC, Giordano T, Orringer MB, Roth JA, Spitz MR, Wistuba II, Ozenberger B, Good PJ, Chang AC, Beer DG, Watson MA, Ladanyi M, Broderick S, Yoshizawa A, Travis WD, Pao W, Province MA, Weinstock GM, Varmus HE, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Gibbs RA, Meyerson M, Wilson RK. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, Cho J, Suh J, Capelletti M, Sivachenko A, Sougnez C, Auclair D, Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Cibulskis K, Choi K, de Waal L, Sharifnia T, Brooks A, Greulich H, Banerji S, Zander T, Seidel D, Leenders F, Ansén S, Ludwig C, Engel-Riedel W, Stoelben E, Wolf J, Goparju C, Thompson K, Winckler W, Kwiatkowski D, Johnson BE, Jänne PA, Miller VA, Pao W, Travis WD, Pass HI, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Thomas RK, Garraway LA, Getz G, Meyerson M. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mäki-Nevala S, Kaur SV, Tuononen K, Lagström S, Ellonen P, Rönty M, Wirtanen A, Knuuttila A, Knuutila S. Mutated ephrin receptor genes in non-small cell lung carcinoma and their occurrence with driver mutations targeted resequencing study on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumour material of 81 patients. Genes Chromo Cancer. 2013;52:1141–1149. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng MF, Ji Y, Wu XB, Ye SG, Chen JY. EphB4 gene polymorphism and protein expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:405–408. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masood R, Kumar SR, Sinha UK, Crowe DL, Krasnoperov V, Reddy RK, Zozulya S, Singh J, Xia G, Broek D, Schönthal AH, Gill PS. EphB4 provides survival advantage to squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1236–1248. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinha UK, Kundra A, Scalia P, Smith DL, Parsa B, Masood R, Gill PS. Expression of EphB4 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82:866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinha UK, Mazhar K, Chinn SB, Dhillon VK, Liu L, Masood R, Rice DH, Gill PS. The association between elevated EphB4 expression, smoking status, and advanced-stage disease in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:1053–1059. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.10.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yavrouian EJ, Sinha UK, Rice DH, Salam MT, Gill PS, Masood R. The significance of EphB4 and EphrinB2 expression and survival in head and neck squamouscell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:985–991. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.9.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferguson BD, Tretiakova MS, Lingen MW, Gill PS, Salgia R. Expression of the EPHB4 receptor tyrosine kinase in head and neck and renal malignancies--implications for solid tumours and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Growth Factors. 2014;32:202–206. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2014.980904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia G, Kumar SR, Masood R, Koss M, Templeman C, Quinn D, Zhu S, Reddy R, Krasnoperov V, Gill PS. Up-regulation of EphB4 in mesothelioma and its biological significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4305–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu R, Ferguson BD, Zhou Y, Naga K, Salgia R, Gill PS, Krasnoperov V. EphB4 as a therapeutic target in mesothelioma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyd AW, Bartlett PF, Lackmann M. Therapeutic targeting of EPH receptors and their ligands. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:39–62. doi: 10.1038/nrd4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unzue A, Lafleur K, Zhao H, Zhou T, Dong J, Kolb P, Liebl J, Zahler S, Caflisch A, Nevado C. Three stories on Eph kinase inhibitors: From in silico discovery to in vivo validation. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;112:347–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pietanza MC, Gadgeel SM, Dowlati A, Lynch TJ, Salgia R, Rowland KM, Jr, Wertheim MS, Price KA, Riely GJ, Azzoli CG, Miller VA, Krug LM, Kris MG, Beumer JH, Tonda M, Mitchell B, Rizvi NA. Phase II study of the multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor XL647 in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:856–865. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824c943f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koolpe M, Burgess R, Dail M, Pasquale EB. EphB receptor-binding peptides identified by phage display enable design of an antagonist with ephrin-like affinity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17301–17311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dines M, Lamprecht R. EphrinA4 mimetic peptide targeted to EphA binding site impairs the formation of long-term fear memory in lateral amygdala. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e450. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han X, Xu Y, Yang Y, Xi J, Tian W, Duggineni S, Huang Z, An J. Discovery and characterization of a novel cyclic peptide that effectively inhibits ephrin binding to the EphA4 receptor and displays anti-angiogenesis activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lamberto I, Lechtenberg BC, Olson EJ, Mace PD, Dawson PE, Riedl SJ, Pasquale EB. Development and structural analysis of a nanomolar cyclic peptide antagonist for the EphA4 receptor. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:2787–279510. doi: 10.1021/cb500677x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riedl SJ, Pasquale EB. Targeting the Eph system with peptides and peptide conjugates. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16:1031–1047. doi: 10.2174/1389450116666150727115934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olson EJ, Lechtenberg BC, Zhao C, Rubio de la Torre E, Lamberto I, Riedl SJ, Dawson PE, Pasquale EB. Modifications of a nanomolar cyclic peptide antagonist for the EphA4 receptor to achieve high plasma stability. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7:841–846. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duggineni S, Mitra S, Noberini R, Han X, Lin N, Xu Y, Tian W, An J, Pasquale EB, Huang Z. Design, synthesis and characterization of novel small molecular inhibitors of ephrin-B2 binding to EphB4. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krasnoperov V, Kumar SR, Ley E, Li X, Scehnet J, Liu R, Zozulya S, Gill PS. Novel EphB4 monoclonal antibodies modulate angiogenesis and inhibit tumour growth. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2029–2038. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kertesz N, Krasnoperov V, Reddy R, Leshanski L, Kumar SR, Zozulya S, Gill PS. The soluble extracellular domain of EphB4 (sEphB4) antagonizes EphB4 EphrinB2 interaction, modulates angiogenesis, and inhibits tumour growth. Blood. 2006;107:2330–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi S, Liu J, Joshi SB, Krasnoperov V, Gill P, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB. Biophysical characterization and stabilization of the recombinant albumin fusion protein sEphB4-HAS. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1969–1984. doi: 10.1002/jps.23096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scehnet JS, Ley EJ, Krasnoperov V, Liu R, Manchanda PK, Sjoberg E, Kostecke AP, Gupta S, Kumar SR, Gill PS. The role of Ephs, Ephrins, and growth factors in Kaposi sarcoma and implications of EphrinB2 blockade. Blood. 2009;113:254–263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Djokovic D, Trindade A, Gigante J, Badenes M, Silva L, Liu R, Li X, Gong M, Krasnoperov V, Gill PS, Duarte A. Combination of Dll4/Notch and Ephrin-B2/EphB4 targeted therapy is highly effective in disrupting tumour angiogenesis. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:641–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Falivelli G, Lisabeth EM, Rubio de la Torre E, Perez-Tenorio G, Tosato G, Salvucci O, Pasquale EB. Attenuation of eph receptor kinase activation in cancer cells by coexpressed ephrin ligands. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kao TJ, Kania A. Ephrin-mediated cis-attenuation of Eph receptor signaling is essential for spinal motor axon guidance. Neuron. 2011;71:76–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carvalho RF, Beutler M, Marler KJ, Knöll B, Becker-Barroso E, Heintzmann R, Ng T, Drescher U. Silencing of EphA3 through a cis interaction with ephrinA5. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:322–330. doi: 10.1038/nn1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tang XX, Brodeur GM, Campling BG, Ikegaki N. Coexpression of transcripts encoding EPHB receptor protein tyrosine kinases and their ephrin-Bligands in human small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:455–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yong CSM, Dardalhon V, Devaud C, Taylor N, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. CAR T-cell therapy of solid tumours. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017;95:356–363. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeltsman M, Dozier J, McGee E, Ngai D, Adusumilli PS. CAR T-cell therapy for lung cancer and malignant pleural mesothelioma. Transl Res. 2017;187:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li K, Pan X, Bi Y, Xu W, Chen C, Gao H, Shi B, Jiang H, Yang S, Jiang L, Li Z. Adoptive immunotherapy using T lymphocytes redirected to glypican-3 for the treatment of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:2496–2507. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morello A, Sadelain M, Adusumilli PS. Mesothelin-Targeted CARs: Driving T cells to solid tumours. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:133–146. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bardelle C, Cross D, Davenport S, Kettle JG, Ko EJ, Leach AG, Mortlock A, Read J, Roberts NJ, Robins P, Williams EJ. Inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase EphB4. Part 1:S-based design and optimization of a series of 2,4-bis-anilinopyrimidines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008a;18:2776–2780. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bardelle C, Nakano M, Sato H, Truesdale AT, Stuart JD, Nartey EN, Hightower KE, Kane-Carson L. Inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase EphB4. Part 2: structure-based discovery and optimisation of 3, 5-bis substituted anilinopyrimidines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008b;18:5717–5721. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miyazaki Y, Nakano M, Sato, Truesdale AT, Stuart JD, Nartey EN, Hightower KE, Kane-Carson L. Design and effective synthesis of novel templates, 3, 7-diphenyl-4-amino-thieno and furo-[3,2-c]pyridines as protein kinase inhibitors and in vitro evaluation targeting angiogenetic kinases. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gendreau SB, Ventura R, Keast P, Laird AD, Yakes FM, Zhang W, Bentzien F, Cancilla B, Lutman J, Chu F, Jackman L, Shi Y, Yu P, Wang J, Aftab DT, Jaeger CT, Meyer SM, De Costa A, Engell K, Chen J, Martini JF, Joly AH. Inhibition of the T790M gatekeeper mutant of the epidermal growth factor receptor by EXEL-7647. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3713–3723. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xia G, Kumar SR, Masood R, Zhu S, Reddy R, Krasnoperov V, Quinn DI, Henshall SM, Sutherland RL, Pinski JK, Daneshmand S, Buscarini M, Stein JP, Zhong C, Broek D, Roy-Burman P, Gill PS. EphB4 expression and biological significance in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4623–4632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumar SR, Singh J, Xia G, Krasnoperov V, Hassanieh L, Ley EJ, Scehnet J, Kumar NG, Hawes D, Press MF, Weaver FA, Gill PS. Receptor tyrosine kinase EphB4 is a survival factor in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:279–293. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xia G, Kumar SR, Stein JP, Singh J, Krasnoperov V, Zhu S, Hassanieh L, Smith DL, Buscarini M, Broek D, Quinn DI, Weaver FA, Gill PS. EphB4 receptor tyrosine kinase is expressed in bladder cancer and provides signals for cell survival. Oncogene. 2006;25:769–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Masood R, Kumar SR, Sinha UK, Crowe DL, Krasnoperov V, Reddy RK, Zozulya S, Singh J, Xia G, Broek D, Schönthal AH, Gill PS. EphB4 provides survival advantage to squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1236–48. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Koolpe M, Burgess R, Dail M, Pasquale EB. EphB receptor-binding peptides identified by phage display enable design of an antagonist with ephrin-like affinity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17301–17311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barlaam B, Ducray R, Lambert-van der Brempt C, Plé P, Bardelle C, Brooks N, Coleman T, Cross D, Kettle JG, Read J. Inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase EphB4. Part 4: Discovery and optimization of a benzylic alcoholseries. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2207–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lafleur K, Huang D, Zhou T, Caflisch A, Nevado C. Structure-based optimization of potent and selective inhibitors of the tyrosine kinaseerythropoietin producing human hepatocellular carcinoma receptor B4 (EphB4) J Med Chem. 2009;52:6433–6446. doi: 10.1021/jm9009444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lafleur K, Dong J, Huang D, Caflisch A, Nevado C. Optimization of inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase EphB4. 2. Cellular potency improvement and binding mode validation by X-ray crystallography. J Med Chem. 2013;56:84–96. doi: 10.1021/jm301187e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kolb P, Kipouros CB, Huang D, Caflisch A. Structure based tailoring of compound libraries for high-throughput screening: discovery of novel EphB4 kinase inhibitors. Proteins. 2008;73:11–18. doi: 10.1002/prot.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu XM, Wu YC, Liu X, Huang XC, Hou XX, Wang JL, Cheng XL, Mao WM, Ling ZG. Cell-Free RNA Content in Peripheral Blood as Potential Biomarkers for Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17111845. pii: E1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yavrouian EJ, Sinha UK, Rice DH, Salam MT, Gill PS, Masood R. The significance of EphB4 and EphrinB2 expression and survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:985–91. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.9.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]