Abstract

Objective

Compare state policies with standards outlined in the 2012 AAP Policy Statement on Levels of Neonatal Care.

Study design

Systematic, web-based review of publicly available policies on levels of care in all states in 2014. Infant risk information, equipment capabilities, and specialty staffing were abstracted from published rules, statutes, and regulations.

Result

Twenty-two states had a policy on regionalized perinatal care. State policies vary in consistency with the AAP Policy, with 60% of states including standards consistent with Level I criteria, 48% Level II, 14% Level III, and one state with Level IV. Ventilation capability standards are highly consistent (66–100%), followed by imaging capability standards (50–90%). Policy language on specialty staffing (44–68%), and subspecialty staffing (39–50%) are moderately consistent.

Conclusion

State policies vary in consistency, a potentially significant barrier to monitoring, regulation, uniform care provision and measurement, and reporting of national-level measures on risk-appropriate care.

Introduction

Infant mortality is a sentinel indicator of the health of a nation [1]. A strategy for reducing infant mortality in the United States (US) is increasing the availability of neonatal intensive care units (NICU) and other resources through perinatal regionalization [2–4]. Perinatal regionalization or risk-appropriate care, is the classification of hospital/facility, health care personnel, and resource capacities to ensure the availability of a full spectrum of services for mothers and infants during pregnancy, labor/delivery, and postpartum [5].

The concept of perinatal regionalization was first articulated in the 1976 Committee on Perinatal Health and March of Dimes publication, Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy (TIOP I) [5]. The report included criteria that delineated maternal and neonatal care into three levels of complexity and recommended referral of high-risk patients to centers with the personnel and resources equipped to handle the degree of risk and severity of illness. At the time, the TIOP I recommendations were widely adopted, as resources for the most complex care were scarce and concentrated in academic centers. TIOP I was recognized as a major contributor to significant declines in infant mortality [2, 3]. Regulation of this recommended regionalized process was maintained by Certificate of Need (CON) laws, critical for states in establishing and monitoring perinatal services and resources, including NICUs, within a regionalized system [6, 7].

By the late 1980s, however, advancements in the universal availability of technology, increases in neonatologists at multiple-level facilities, and changes in insurance reimbursements began to weaken the success of this system [2, 8, 9]. Furthermore, interpretation and application of the framework for classifying NICUs varied widely within the United States [10]. Despite subsequent updates in TIOP recommendations [11, 12] and in the absence of a national definition, deregionalization and variability in level-of-care designation continued [2, 9, 13]. To address this issue, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists produced the Guidelines for Perinatal Care (GPC), a set of guidelines focused on care provision for pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates, updated periodically as technology, equipment availability, and care standards advanced [14–16]. The AAP followed with additional policy statements specifically targeting levels of neonatal care in 2004 and 2012 [10, 17]. The goal of the policy statements was to support development of uniform levels of care definitions by expanding the TIOP definitions, stratifying services into levels based on facility capability, severity of illness, birth weight, and gestational age. The AAP policy statements, in alignment with the GPC, emphasized the importance of well-defined regionalized systems of perinatal care with uniform definitions to provide a basis for comparison of outcomes, resource use, and health care costs.

No federal regulations or national standard definitions were ever developed for designating levels of neonatal care [17], despite the TIOP and AAP policy statements, and the well-documented positive impact on high-risk neonatal outcomes. Furthermore, incorporation into national objectives including the Healthy People 2020 Objective (increase the proportion of very-low-birth-weight infants born at Level III hospitals or subspecialty perinatal centers—MICH-33), and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) National Performance Measure 17 (percent of very-low- birth-weight infants delivered at facilities for high-risk deliveries and neonates) also had minimal impact on developing a national standard [18, 19]. Rather, the implementation of risk-appropriate care is defined by each state, a finding by Blackmon et al. [20], who conducted a national-level systematic review of neonatal care definitions, criteria language, and regulatory requirements. They concluded that AAP policy statements could serve as the foundation for developing consistency among state definitions and designated levels of care services. The conclusions, however, did not assess state adherence to AAP policy statements. The purpose of this research is to provide evidence for further assessing state policy adherence by (1) comprehensively reviewing state-level policy standards on neonatal care designations and capability criteria in the 50 states; and (2) systematically comparing consistency of state-level policy standards to those outlined in the GPC 7th edition/2012 AAP policy statement (AAP Policy).

Materials and methods

Study design and data collection process

A systematic, web-based review of publicly available information on hospital levels of neonatal care policies and legislation was conducted for all 50 states from January to June, 2014. All policies and legislation published by state agencies or state governments were examined for inclusion. Facility-level and/or hospital system policies were not included unless associated with state legislation addressing care levels. The available state-level policies, rules, codes, licensure regulations, health-planning documents, and state agency program descriptions (e.g., Public Health Codes, Certificate of Need or state licensing, State Health Plans, legislative bills, service rules and standards, etc.) were identified for data extraction using search engines such as Google and Bing. We applied a standardized search strategy based on multiple search terms including a broad grouping of policies (Table 1), followed by a comprehensive search of State Health Department websites. Search terms were amended as information was located for review, and expanded based on language identified in policies and legislation.

Table 1.

Summary of search terms used for data collection and abstraction

| Individual Search Terms (‘State’ was included in subsequent searches and variations of search phrases were subsequently searched) |

|---|

| [state] neonatal levels of care |

| [state] perinatal levels of care |

| [state] levels of care |

| [state] neonatal policy [ies] |

| [state] perinatal policy [ies] |

| [state] NICU policy [ies] |

| [state] Level I neonatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level I perinatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level I policy [ies] |

| [state] Level II neonatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level II perinatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level II policy [ies] |

| [state] Level III neonatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level III perinatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level III policy [ies] |

| [state] Level IV neonatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level IV perinatal policy [ies] |

| [state] Level IV policy [ies] |

| [state] neonatal program |

| [state] perinatal program |

| [state] regionalized program |

| [state] perinatal regionalization |

| [state] perinatal regional center |

| [state] perinatal quality collaborative |

| [statel health plan |

Review and abstraction of data were refined to identify within-policy language on levels of neonatal care designations, clinical capability criteria, resources level, minimum staffing, and patient volume requirements. Data groupings were based on the framework of the AAP Policy [16, 17]. We divided the United States into ten HRSA geographic regions in order to facilitate an organized review and abstraction process. Information was captured by four abstractors using a standardized template developed by the authors. State policies in a region were searched separately by two abstractors. Each abstractor then independently cross-referenced the search findings of the other following double data entry. Study authors further validated 20% of the abstracted information. Discrepancies were reconciled during in-person meetings among study researchers to ensure consistency in the search strategy and data entry. To verify accuracy of the web-based search, 10% of states were contacted to confirm the identification of all publicly available policies.

Study definitions

We developed the following resource criteria: (1) infant risk information including language on gestational age and/or birth weight; (2) technology and equipment, particularly, ventilation and imaging capabilities; and (3) availability of appropriate staffing defined as pediatric surgical specialties and subspecialties. We focused on surgical staffing and surgical subspecialty capabilities, as these were added in the AAP Policy to define provision of higher-level services.

For each of the criteria noted above, we classified abstracted state policy and legislation language using capability and resource standards as defined within the AAP Policy (Table 2).

Infant risk information (i.e., gestational age and/or birth weight) was categorized as present (i.e., specified) if included in the policy or absent (i.e., not specified) if not included within the policy.

For ventilation capabilities, policy language was categorized as specified and comprehensive if provision of a full range of complex respiratory support including conventional and/or high-frequency ventilation and inhaled nitric oxide; brief mechanical ventilation or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with transfer as needed; or neonatal resuscitation and stabilization with transfer as needed, were mentioned.

Imaging and monitoring capabilities were categorized as comprehensive if there was advanced physiologic monitoring equipment including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, echocardiography, or portable equipment including X-ray with transfer as needed were mentioned.

Pediatric surgical and surgical subspecialty capabilities were categorized as comprehensive if a full range of surgical services were available on-site, or readily accessible services by consultation were mentioned.

Table 2.

Defined minimum criteria and categories for each level of neonatal care using the 2012 AAP policy

| Criteria | Categoriesa | Level Ib | Level IIc | Level III | Level IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight | Specified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gestational age | Specified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ventilation capabilities | Full range or complex respiratory support; conventional and/or high-frequency ventilation; and inhaled nitric oxide | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mechanical ventilation and/or CPAP (transfer as needed) | ✓ | – | – | ||

| Neonatal resuscitation and stabilization (transfer as needed) | ✓ | – | – | – | |

| Imaging capabilities | Advanced physiologic monitoring equipment including tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or echocardiography | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Equipment including portable X-ray (transfer as needed) | ✓ | – | – | ||

| Pediatric surgical capabilities | Full range available on-site | ✓ | |||

| Readily accessible by consultation | ✓ | – | |||

| Pediatric surgical subspecialty capabilities | Full range available on-site | ✓ | |||

| Readily accessible by consultation | ✓ | – |

Criteria with multiple categories are listed from highest capability to lowest capability

Blank spaces indicate that the AAP Policy does not require those criteria to be defined for that level of neonatal care. States may include these capabilities in a policy to provide higher-level care to neonates

Dashes in columns represent capabilities inconsistent with the minimum standard required for that level of care as defined by the AAP Policy.

Includes National Resuscitation Program referenced within a policy

Level-of-care classification and definitions of consistency

Abstracted language was classified to a level of neonatal care consistent with specifications for criteria and categories described in the AAP Policy. State policies classifying levels using older guidelines (e.g., 2004 AAP Policy), were reviewed and reclassified using the new policy [16]. For example, policies that referenced hospitals with language on subspecialty or intensive capabilities and were classified as Level IIIA or IIIB in earlier AAP policies, were reclassified as Level III.

We compared the consistency of state policy category standards to those outlined in the AAP Policy. Each category within each criterion was reviewed to determine the capabilities most consistent with the AAP Policy level of care classifications to least consistent (e.g., Level III imaging capabilities including language on advanced physiologic monitoring were most consistent, while portable X-ray alone would be least consistent (Table 2)). All capabilities were considered least consistent with the AAP Policy if only referenced, but not specified. Criteria included but not required for a specific level (e.g., surgical capabilities at a Level I hospital) were also categorized, but noted as “not applicable” for that level of care when examined for consistency with the policy. States without policies on levels of care were excluded from analysis. All state data were summarized by category and level of care.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the abstracted information. State criteria were compared with the AAP Policy to determine the proportion of states consistent with policy standards. The comparison included determining the proportion of policies consistent with each criterion within a level, and those consistent with all criteria for each level. The primary outcome was the number of states fully consistent across all levels of care. Counts and percentages of states with identified policies or legislation were reported and variations were described. This study was determined not to need Institutional Review Board review at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention because it did not include human subjects.

Results

Twenty-two states (44%) had policy language on at least one level of care, while 15 states had language on all four levels of care (30%). Of the seven states with less-comprehensive policy language, Kentucky and Maryland had no language defining Level I criteria, Maryland had no language defining Level II, and Iowa, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Pennsylvania had no language defining Level IV (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of states classified by criteria and category using 2014 state-level policy language for each level of neonatal care as defined in the 2012 AAP policy

| Criteria | Number and percentage of states with developed policies for each level of neonatal carea

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Level Ib States with policy (N = 20)c |

Level II States with policy (N = 21) |

Level III States with policy (N =22) |

Level IV States with policy (N =18) |

|

| Birth weight | Specified states | GA, IL, NJ, NY, SC, TN, UT, and VA | FL, GA, IL, IA, KY, LA, MS, NJ, NY, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | FL, MD, MS, NJ, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, and WA | FL, GA, MD, OH, SC, TN, and UT |

| Count (%) | 8 (40.0%) | 15 (71.4%) | 10 (45.5%) | 7 (38.9%) | |

| Not specified states | AL, CA, FL, IA, LA, MA, MS, NV, NC, OH, PA, and WA | AL, CA, MA, NV, NC, and OH | AL, CA, GA, IL, IA, KY, LA, MA, NV, NY, NC, and VA | AL, CA, IL, KY, LA, MS, NJ, NY, NC, VA, and WA | |

| Count (%) | 12 (60.0%) | 6 (28.6%) | 12 (54.5%) | 11 (61.1%) | |

| Gestational age | Specified states | GA, IL, MA, MS, NJ, NY, OH, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | GA, IL, IA, KY, MA, MS, NJ, NY, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, and WA | KY, MD, MA, MS, NJ, NC, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, and WA | GA, MD, NC, OH, TN, and UT |

| Count (%) | 12 (60.0%) | 14 (66.7%) | 12 (54.5%) | 6 (33.3%) | |

| Not specified states | AL, CA, FL, IA, LA, NV, NC, and PA | AL, CA, FL, LA, NV, NC, and VA | AL, CA, FL, GA, IL, IA, LA, NV, NY, and VA | AL, CA, FL, IL, KY, LA, MS, NJ, NY, SC, VA, and WA | |

| Count (%) | 8 (40.0%) | 7 (33.3%) | 10 (45.5%) | 12 (66.7%) | |

| Ventilation capabilities | Full range or complex respiratory support; conventional and/or high-frequency ventilation; and inhaled nitric oxide states | FL, GA, KY, LA, MA, MS, NY, PA, SC, TN, UT, and WA | FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NJ, NY, TN, SC, UT, VA, and WA | ||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (54.5%) | 12 (66.7%) | |

| Brief mechanical ventilation and/or CPAP (transfer as needed) states | CA | CA, FL, GA, IL, IA, LA, MA, MS, NC, NJ, NV, NY, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | AL, IL, IA, MD, NV, NC, OH, and VA | CA, MD, NC, and OH | |

| Count (%) | 1 (5.0%) | 19 (90.5%) | 8 (36.5%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Neonatal resuscitation and stabilization (transfer as needed) states | AL, FL, GA, IL, IA, LA, MA, MS, NV, NJ, NY, NC, OH, PA, TN, SC, UT, VA, and WA | AL and KY | NJ | ||

| Count (%) | 19 (95.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Not specified states | CA | AL and IL | |||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Imaging capabilities | Advanced physiologic monitoring equipment including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or echocardiography states | OH | AL, IL, KY, MD, MA, MS, OH, TN, SC, UT, and WA | AL, IL, KY, MD, MS, NY, NC, OH, TN, SC, UT, and WA | |

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 11 (50.0%) | 12 (66.7%) | |

| Portable equipment including X-ray (transfer as needed) states | AL, GA, IL, IA, MA, MS, NC, NY, OH, PA, TN, VA, and WA | AL, FL, GA, IL, IA, KY, LA, MA, MS, NV, NY, NC, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | FL, IA, LA, NY, NC, PA, and VA | GA, LA, and VA | |

| Count (%) | 13 (65.0%) | 18 (85.7%) | 7 (31.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | |

| Not specified states | CA, FL, LA, NV, NJ, SC, and UT | CA and NJ | CA, GA, NV, and NJ | CA, FL, and NJ | |

| Count (%) | 7 (35.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 4 (18.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | |

| Pediatric surgical capabilities | Full range available on-site | FL, IL, and IA | FL, GA, KY, MD, MS, SC, UT, and VA | ||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (13.7%) | 8 (44.5%) | |

| Readily accessible by consultation | MA and NY | GA, KY, LA, MD, MA, MS, NV, NY, SC, TN, UT, and WA | IL, LA, NY, NC, TN, and WA | ||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 12 (54.5%) | 6 (33.3%) | |

| Surgery not recommended in a policy for a specified level | NJ | ||||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Not specified | AL, CA, FL, GA, IL, IA, LA, MA, MS, NV, NJ, NY, NC, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | AL, CA, FL, GA, IL, IA, KY, LA, MS, NV, NC, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | AL, CA, NJ, NC, OH, PA, and VA | AL, CA, NJ, and OH | |

| Count (%) | 20 (100.0%) | 18 (85.7%) | 7 (31.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Pediatric surgical subspecialty capabilities | Full range available on-site | FL and IL | FL, GA, KY, MS, SC, UT, and VA | ||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.0%) | 7 (38.9%) | |

| Readily accessible by consultation | GA, LA, MD, MA, NY, OH, SC, TN, and UT | IL, LA, MD, NY, OH, TN, and WA | |||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (41.0%) | 7 (38.9%) | |

| Surgery not recommended in a policy for a specified level | FL and NJ | ||||

| Count (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Not specified | AL, CA, FL, GA, IL, IA, LA, MA, MS, NV, NJ, NY, NC, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | AL, CA, GA, IL, IA, KY, LA, MA, MS, NV, NY, NC, OH, PA, SC, TN, UT, VA, and WA | AL, CA, IA, KY, MS, NV, NJ, NC, PA, VA, and WA | AL, CA, NJ, and NC | |

| Count (%) | 20 (100.0%) | 19 (90.5%) | 11 (50.0%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

Some states may only publish policies for certain levels. The ‘N located in each column represents the number of states with a published policy for that level

State-used alternative terms for Level I = Basic, General; Level II = Specialty, Intermediate; Level III = Subspecialty, Intensive; and Level IV = Regional Center

States with policies are defined as having any long-standing policy related to levels of care which may or may not be consistent with the minimum requirements in the 2012 AAP Policy

Includes National Resuscitation Program referenced within a policy

Infant risk information

Less than half of state Level III (46%) and IV (39%) policies included language on birth weight standards, while almost three-quarters of state Level II policies included birth weight standards (71%; Table 3). By contrast, more than half of state Level I (60%), II (67%), and III (55%) policies specified gestational age standards, while only one-third of state Level IV (33%) policies specified gestational age standards.

Equipment capabilities

All state Level I policies included language on neonatal resuscitation and stabilization standards (100%), and most state Level II policies included language on brief mechanical ventilation or CPAP standards (91%; Table 3). The majority of state Level III (55%) and IV (67%) policies included language on a full range of respiratory support including conventional or high-frequency ventilation and inhaled nitric oxide, followed by language on brief mechanical ventilation/CPAP (Level III—37%; Level IV—22%). The available portable imaging equipment, including X-ray machines or provision of advanced imaging capabilities was present in the majority of state Level II policies (86%). Advanced physiologic monitoring equipment was included in policy language for half of state Level III (50%) and two-thirds of state Level IV policies (67%).

Pediatric surgical and subspecialty staffing

Approximately two-thirds (68%) of state Level III policies included language on pediatric surgical capabilities as readily accessible by consultation (Table 3). Almost half of state Level IV policies (45%) included language on a full range of pediatric surgical capabilities available on-site. Half (50%) of state Level III policies included language on pediatric surgical subspecialties as readily accessible by consultation. More than one-third (39%) of state Level IV policies included language on a full range of pediatric surgical subspecialties available on-site.

Consistency with AAP policy

While all state Level I policies were consistent with appropriate ventilation capabilities, only 60% of states had Level I policy language consistent with gestational age requirements (Table 4). For Level II policies, most states (67–90%) included consistent language on infant risk information and appropriate capabilities. Almost half to more than two-thirds (45–68%) of state Level III policies included consistent language on infant risk information, capabilities, and staffing. Among state Level IV policies, consistency with the AAP 2012 Policy ranged from 33 to 67%, with the highest consistency for equipment capabilities.

Table 4.

Descriptive summary of the state overall and within-criteria consistency with the 2012 AAP policy

| Consistency within Levels | AAP 2012 Policya

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I States with Policy (N = 20) |

Level II States with Policy (N = 21) |

Level III States with Policy (N = 22) |

Level IV States with Policy (N = 18) |

|

| States consistent with all criteria within each level of careb | 12 (60.0%) | 10 (47.6%) | 3 (13.7%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| States consistent by criteriac | ||||

| Birth weight | N/Ad | 15 (71.4%) | 10 (45.5%) | 7 (38.9%) |

| Gestational age | 12 (60.0%) | 14 (66.7%) | 12 (54.5%) | 6 (33.3%) |

| Ventilation capabilities | 20 (100.0%) | 19 (90.5%) | 12 (54.5%) | 12 (66.7%) |

| Imaging capabilities | N/A | 19 (90.5%) | 11 (50.0%) | 12 (66.7%) |

| Pediatric surgical capabilities | N/A | N/A | 15 (68.2%) | 8 (44.5%) |

| Pediatric surgical subspecialty | N/A | N/A | 11 (50.0%) | 7 (38.9%) |

Some states may only publish policies for certain levels. The ‘N’ located in each column represents the number of states with a published policy specifically defining that level

To be included, a state must be consistent with all criteria

To be included as consistent with each specific criterion, the state must have policy language that includes the minimum capabilities and/or more advanced capabilities, consistent with the AAP Policy

N/A, or not applicable, is used for levels referenced in the 2012 AAP Policy that do not require those criteria to be defined

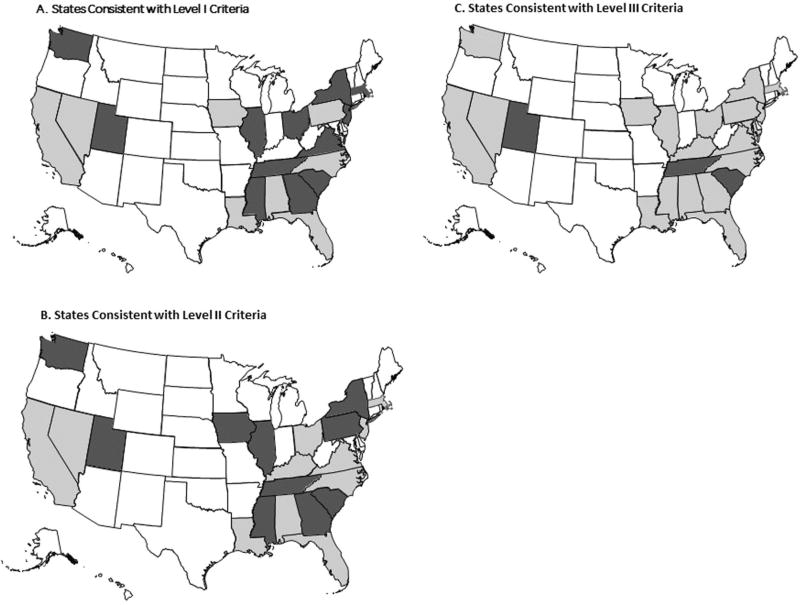

In total 12 (60%) state Level I policies met all AAP Policy criteria included in this study (Fig. 1a). A little less than half, or 10 of state Level II policies were consistent with the policy, while three (18%) state Level III policies met all policy criteria (Fig. 1b, c). Only one state, Utah, was consistent with all Level IV policy criteria (not shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a White represents states without a Level I policy (N = 30); light gray represents states with a Level I policy but not consistent with the 2012 AAP Policy (N = 8); and dark gray represents states with a Level I policy and consistent with the 2012 AAP Policy criteria (N = 12). b White represents states without a Level II policy (N = 29); light gray represents states with a Level II policy but not consistent with the 2012 AAP Policy (N = 11); and dark gray represents states with a Level II policy and consistent with the 2012 AAP Policy criteria (N = 10). c White represents states without a Level III policy (N = 28); light gray represents states with a Level III policy but not consistent with the 2012 AAP Policy (N = 19); and dark gray represents states with a Level III policy and consistent with the 2012 AAP Policy criteria (N = 3)

Discussion

Only 22 states had policy language addressing neonatal care designations and capability criteria. Of these, seven did not define four distinct levels of care. Within states, consistency varied between each criterion. Although infant risk information, technology and equipment capabilities, and surgical staffing are clear criteria for describing levels of risk-appropriate neonatal care, there were distinct gaps in criteria consistency across and within states, potentially impacting monitoring and adherence.

That 28 states do not yet have policy language addressing neonatal levels of care, as defined by the AAP Policy, highlights the complex relationship between clinical evidence and policy change, despite evidence that adopting these policy changes can lead to increases in revenue, patient volume and services, and decreases in morbidity [21–25]. The success achieved with the uptake of risk-appropriate care in the 1970s and 80s was due to the commitment of perinatal leaders and hospitals that advocated for the concept [8]. Continuing engagement of the larger health care community, including providers, administrators, and insurers, to embrace the importance of a standardized system and collaborative information exchange, not only improves patient care [26–28], but bridges the gap between clinical evidence and policy.

Study results indicate distinct gaps in criteria consistency within states. With such criteria variation in policy standards, provision of care cannot be consistently evaluated or enforced by regulatory entities. Lasswell et al. [29] determined that delivery of a very low birth weight or very preterm infant outside of a Level III hospital increased the likelihood of neonatal death; however, quality of care, including clearly defined capabilities and standards, within Level III hospitals could not be assessed. Recent research in California, by Profit et al. [30], indicates that quality of care for very-low-birth-weight infants varies across NICU, but not by facility level. They conclude that the current variability in approach to defining level of care, including facility self-designation, may result in misclassification of care levels [30, 31]. Without consistent implementation and regulatory oversight, noncompliance with established standards could impact neonatal outcomes. Staebler [32] described four options for risk-appropriate care implementation, oversight, and monitoring: (1) continue the current system of state-level regulation, (2) develop localized regional systems for oversight and monitoring—these systems currently exist in metropolitan areas, (3) develop gradual state or federal oversight and monitoring, and (4) designate regional perinatal care systems with formal oversight at the state level, and federal implementation standards that equitably allocate resources. The first two options are currently in place throughout the United States, and inconsistency with policy criteria, identified in this review, indicates these as ineffective strategies for ensuring uniform, risk-appropriate care delivery because they promote gaps in criteria capabilities even for the highest-level facilities. Option 4 supports regulation of facilities at the state level, and through uniform reporting, accountability at the federal level. Option 4 is the most plausible for ensuring state-level policies that set standards for hospital/facility quality assurance and improvement.

Additionally, the implementation of option 4 would improve the precision of existing national performance measures through development and reporting of facility or state-based continuous quality improvement initiatives. Although the HRSA and HP2020 performance measures represent a consistent national standard, current measurement is not reflective of state-level policy standards. Moreover, the AAP Policy recommends uniform classification of the functional capabilities and staffing of facilities providing inpatient care for neonates [17], but current standard measurement for national comparisons is missing. Filling this gap, utilization of population-based data as a standard, would support consistent implementation of uniform processes for regulation of services among all inpatient care facilities.

Since the release of the AAP Policy and this review, 4 years have elapsed for states to adopt current policy and practice consistent with the new statement. Recent assessments suggest that state systems are at various stages of policy amendment and adoption, and implementation of regionalized systems between and within states [22, 33]. Revisions between the 2004 and 2012 AAP Policies include development of a Level IV definition, further defining surgical subspecialty standards [34]—a necessary requirement for defining facility-based comprehensive services. In response, some states and regions have partnered to establish collaborative neonatal networks that widely disseminate evidence-based practice through continuous quality improvement in the NICU setting (e.g., Vermont Oxford Network, Pediatrix Medical Group, Perinatal Quality Collaboratives, Regional Centers, etc.) [35], and focus on interfacility transport of high-risk patients or telemedicine as an alternative method to provide high-quality risk-appropriate care [36–44]. These strategies support continued advancement of care standards, while state legislative processes conform to new policies and clinical guidance. In the end, states that fully adopt the AAP Policy would facilitate an all-facility upgrade, resulting in increased cost containment, mandated referrals, data reporting, reimbursement restructuring, and regulation enforcement [32].

This review was limited as researchers did not directly contact all states to confirm or obtain additional information regarding state policies. Outcome data by facility were not obtained for this study. Additionally, policymakers were not contacted to explain the direct application of the existing policies. Unpublished policies were excluded from this review, and changes occurring in state policies following the data collection phase were not included. Abstractors and researchers interpreted publicly available information, and systematically categorized it into criteria based on the AAP Policy. Although validation and a consensus process was used, it is possible that some policies were misclassified in the review process.

Conclusion

The AAP Policy outlines minimal criteria for provision of neonatal risk-appropriate care. Less than half of state policies are in various stages of revision and adoption, and the remaining states do not have identifiable policy language on regionalized care. Lack of state policy and variation in existing language limits comparison of patient outcomes, resource use, and costs. Standardizing care by facility level through state policies allows for development of uniform monitoring and assessment procedures both within and across the United States. When all states adopt the AAP Policy, including those currently with no policy in place, all facilities will function at the same level-of-care standard, resulting in monitoring and regulation consistency in facility-level implementation. This will lead to standard national performance measurement and reporting reflecting the current volume of at-risk neonates born in the most appropriate facilities—all achievable goals in the early 21st century, in alignment with the updated AAP Policy Statement and the most recent version of the GPC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the data abstractors for contributing to the body of this work: Mary Charlotte Tate, Kim Tubbs Ramsay, Renyea M. Colvin, MPH, and Tracie Herold, LCSW. We would also like to thank Evelyn Interis, MPH, and Amy M. Williams, MPH, for the literature search and review, and Elizabeth Martin for facilitating management and coordination of the data abstractors and researchers. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the contributions of Alex Monroe Smith, who validated the data tables for this paper.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.MacDorman M, Matthews T, Mohagoo A, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmstrom S, Phibbs C. Regionalization and mortality in neonatal intensive care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:617–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman D, Fisher E, Little G, Stukel T, Chang C, Schoendorf K. The relation between the availability of neonatal intensive care and neonatal mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1538–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick M, Richardson D. Access to neonatal intensive care. The Future of Children. 1995;5:162–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy. Recommendations for the Regional Development of Maternal and Perinatal Health Services. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloan F, Steinwald B. Effects of regulation on hospital costs and input use. J Law Econ. 1980;23:81–109. doi: 10.1086/466953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Improving Health Care. A Dose of Competition: Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commision. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnon D, Allison-Cooke S, Schwartz R. Perinatal care: the threat of deregionalization. Pediatr Ann. 1988;17:447–52. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19880701-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung J, Phibbs C, Boscardin W, Kominski G, Ortega A, Needleman J. The effect of neonatal intensive care level and hospital volume on mortality of very low brith weight infants. Med Care. 2010;48:635–44. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbe887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark A. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1341–47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The 90s and Beyond. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes; 1993. Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enhancing Perinatal Health Through Quality, Safety, and Performance Initiatives. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes; 2011. Toward Improving the Outcome of Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell E, Richardson D, Ginsberg P, Foot B. Deregionalization of neonatal intensive care in urban areas. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:119–24. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 5. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 6. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 7. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levels of Neonatal Care: Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Pediatrics. 2012;130:587–597. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed 26 Feb 2015];Healthy People 2020: Maternal, Infant, and Child Health Measure 33. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives.

- 19.Freeman V. Very low birth weight babies delivered at Facilities for high-risk neonates: a review of title v national performance measure 17: maternal and child health bureau. Health Resources and Services Administration; 2010. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackmon L, Barfield W, Stark A. Hospital neonatal services in the united states: variation in definitions, criteria, and regulatory status, 2008. J Perinatal. 2009;29:788–94. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phibbs C, Baker L, Caughey A, Danielsen B, Schmitt S, Phibbs R. Level and volume of neonatal intensive care and mortality in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2165–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorch S, Baiocchi M, Ahlberg C, Small D. The differential impact of delivery hospital on the outcomes of premature infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130:270–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Synnes A, MacNab Y, Qiu Z, Ohlsson A, Gustafson P, Dean C, et al. Neonatal intensive care unit characteristics affect the incidence of severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Med Care. 2006;44:754–59. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000218780.16064.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogowski J, Horbar J, Pisek P, Baker L, Deterding J, Edwards W, et al. Economic implications of neonatal intensive care unit collaborative quality improvement. Pediatrics. 2001;107:23–29. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horbar J, Rogowski J, Pisek P, Delmore P, Edwards W, Hocker J, et al. Collaborative quality improvement for neonatal intensive care. NIC/Q project investigators of the Vermont oxford network. Pediatrics. 2001;107:14–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobrez D, Gerber S, Budetti P. Trends in perinatal regionalization and the role of managed care. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:839–45. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000232557.84791.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorch S, Martin A, Ranada R, Srinivas S, Grande D. Lessons for providers and hospitals from Philadelphia’s obstetric services closures and consolidations, 1997–2012. Health Aff. 2014;33:2162–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorch S. Ensuring acces to the appropriate health care professionals: regionalization and centralization in a new era of health care financing and delivery. J Am Med Assoc Pediatrics. 2015;169:11–12. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasswell S, Barfield W, Rochat R, Blackmon L. Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304:992–1000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Profit J, Gould J, Bennett M, Goldstein B, Draper D, Phibbs C, et al. The association of level of care with NICU quality. Pediatrics. 2016;137 doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Profit J, Wise P, Lee H. Consequences of the affordable care act for sick newborns. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1284–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staebler S. Regionalized systems of perinatal care: health policy considerations. Adv Neonatal Care. 2011;11:37–42. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e318206fd5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nowakowski L, Barfield W, Kroelinger C, Lauver C, Lawler M, White V, et al. Assessment of state measures of risk appropriate care for very low birth weight infants and recommendations for enhancing regionalized systems. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:217–27. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0721-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bezner S, Bernstein I, Oldham K, Goldin A, Fischer A, Chen L. Pediatric surgeons’ attitudes toward regionalization of neonatal surgical care. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1475–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah V, Warre R, Lee S. Quality improvement initiatives in neonatal intensive care unit networks: achievements and challenges. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:S75–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall R, Hall-Barrow J, Garcia-Rill E. Neonatal regionalization through telemedicine using a community based research and education core facility. Ethn Dis. 2010;20:136–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim E, Teague-Ross T, Greenfield W, Williams D, Kuo D, Hall R. Telemedicine collaboration improves perinatal regionalization and lowers statewide infant mortality. J Perinatal. 2013;33:725–30. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okoroh E, Kroelinger C, Goodman D, Lasswell S, Williams A, Barfield W. United States and Territory policies supporting maternal and neonatal transfer: review of transport and reimbursement. J Perinatal. 2016;36:30–34. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dukhovny D, Dukhovny S, Pursley D, Escobar G, McCormick M, Mao W. The impact of maternal characteristics on the moderately premature infant: an antenatal maternal transport clinical prediction rule. J Perinatal. 2012;32:532–38. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gould J, Danielsen B, Bollman L, Hackel A, Murphy B. Estimating the quality of neonatal transport in California. J Perinatal. 2013;33:964–70. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stroud M, Trautman M, Meyer K, Moss M, Schwartz H, Bigham M, et al. Pediatric and neonatal interfacility transport: results from a national consensus conference. Pediatrics. 2013;132:359–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCoy M, Makkar A, Foulks A, Legako E. Establishing level II neonatal services in Southwestern Oklahoma. J Oklahoma Med Assoc. 2014;107:493–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okoroh E, Kroelinger C, Smith A, Goodman D, Barfield W. US and territory telemedicine policies: identifying gaps in perinatal care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:772e.771–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brantley M, Davis N, Goodman D, Callaghan W, Barfield W. Perinatal regionalization: a geospatial view of perinatal clinical care, United States, 2010–2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:185e.181–185e.110. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]