Summary

This review details tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) biology and its role in sleep, and describes how TNF medications influence sleep/wake activity. Substantial evidence from healthy young animals indicates acute enhancement or inhibition of endogenous brain TNF respectively promotes and inhibits sleep. In contrast, the role of TNF in sleep in most human studies involves pathological conditions associated with chronic elevations of systemic TNF and disrupted sleep. Normalization of TNF levels in such patients improves sleep. A few studies involving normal healthy humans and their TNF levels and sleep are consistent with the animal studies but are necessarily more limited in scope. TNF can act on established sleep regulatory circuits to promote sleep and on the cortex within small networks, such as cortical columns, to induce sleep-like states. TNF affects multiple synaptic functions, e.g. its role in synaptic scaling is firmly established. The TNF-plasticity actions, like its role in sleep, can be local network events suggesting that sleep and plasticity share biochemical regulatory mechanisms and thus may be inseparable from each other. We conclude that TNF is involved in sleep regulation acting within an extensive tightly orchestrated biochemical network to niche-adapt sleep in health and disease.

Keywords: Tumor necrosis factor alpha, sleep regulation, autoimmunity, plasticity, sleep function, brain organization of sleep

Introduction

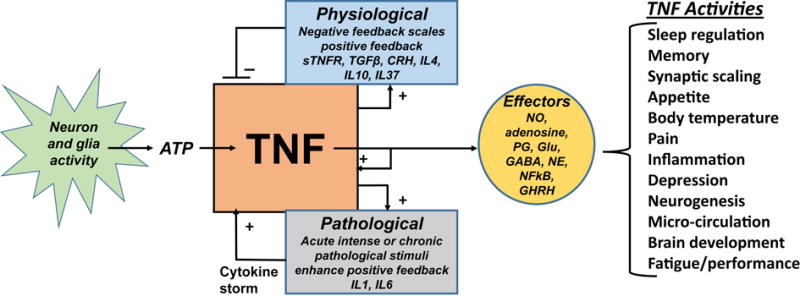

Sleep remains a fundamental scientific enigma. Although significant progress has been made in elucidating roles for sleep in cognition and brain health, the primary functions of sleep have not been firmly established. Moreover, the regulation of sleep and wake is complex and not fully understood, and newer questions have arisen regarding the role and need for local sleep within a specific brain region versus more generalized sleep states. We do, however, appreciate that sleep manifestations are systemic. Sleep affects almost every physiological function, e.g. body temperature, hormone secretions, and respiratory, cardiac, kidney, and immune functions. Sleep actions on the brain range from altering multiple pathologies to recovery from them, as well as performance, mentation, emotion, learning and memory, etc. At the same time, many physiological functions affect sleep, e.g. body temperature, hunger, sexual drive, development, respiration, etc. and extracellular signals involved in the regulation of these functions affect sleep [1]. This latter point is critical to appreciate, as these physiological effects are not accounted for within the two-process (homeostasis and circadian) regulation of sleep model [2]. Figure 1 illustrates some of the known components of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) regulation and TNF biological activities that are also linked to sleep. Although the biochemical network shown is incomplete, it and the more extensive network (not shown) are likely beyond the capacity of any individual’s ability to fully understand the dynamic nuances of such networks. Further, how the components interact with other TNF-regulated processes to orchestrate sleep niche adaptation further challenges comprehension. Herein we focus on only one sleep regulatory substance, TNF. We do so in recognition that other molecules are also involved in sleep regulation, but focus on TNF to illustrate principles of physiological sleep regulation and function. The reader is referred to other reviews for broader treatments of sleep regulation, both biochemical [3–9], neurobiological [10, 11], and glialogical [12–15].

Figure 1.

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) regulation in health and disease and its sleep-linked effectors and actions. Physiological regulation of TNF (upper pathway) includes dampening of TNF production via negative feedback. In contrast, pathogenic stimuli can lead to overwhelming positive feedback (lower pathway). TNF can induce its own and other pro-inflammatory cytokines to amplify host-defense reactions to pathological challenges. Clinically this positive feedback can lead to a cytokine storm with the persistence of intense pathological stimuli. Figure abbreviations: CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; GHRH, growth-hormone-releasing hormone; Glu, glutamic acid; IL, interleukin; NE, norepinephrine; NFkB, nuclear factor kappa B; NO, nitric oxide; PG, prostaglandins; sTNFR, soluble TNF receptor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor β.

TNF biology

Within the brain, TNF has many functions including mediation of brain damage, e.g. cerebral ischemia [17], cerebral blood flow, neuro-protection, responses to infection, and synaptic scaling [18]. TNF is expressed by microglia, astrocytes, and neurons [19–22]. The actions of TNF depend not only on the receptor type – either 55 kilo-Daltons (kD) or 75 kD – and adaptor proteins, but also on the context of the stimulus and the interaction with substances that modify TNF activity. In addition, TNF influences whole organism functions such as body temperature [23, 24], appetite [25], cognition [26], and brain development [27].

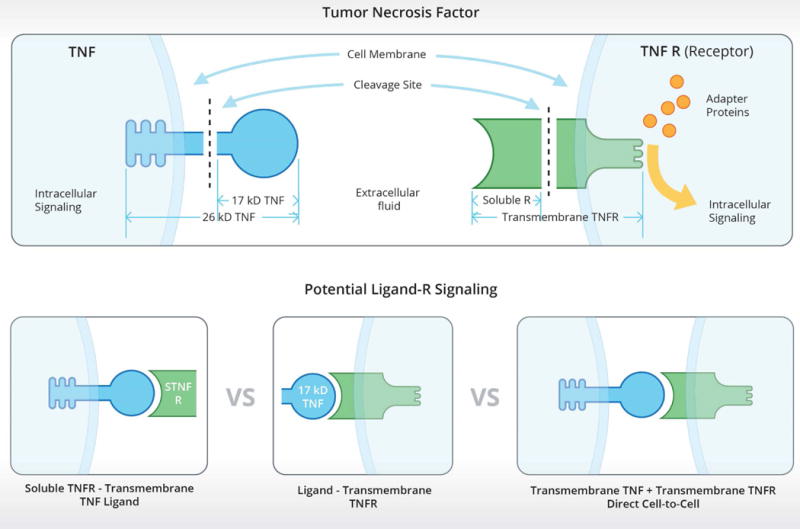

The mechanism of TNF signaling is extensively studied due to its broad influence on physiologic and pathophysiologic processes (Figure 1) [28–36]. The TNF ligand has two forms, a 26 kD trans-membrane protein [31] and a soluble 17 kD protein. Trans-membrane 26 kD TNF predominates in the brain [37] and fat tissue [38]. In contrast the soluble 17 kD form is, for example, more abundent in muscle and liver [ibid]. Soluble 17 kD TNF is first transcribed as the trans-membrane 26 kD form, then cleaved by TNF converting enzyme (Figure 2) to yield the soluble 17 kD TNF form. The regulation of TNF is tissue-specific [39]. Production is driven in part via nuclear factor kappa B and TNF can induce its own expression through this regulatory pathway.

Figure 2.

Potential tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) signaling mechanisms. The upper box illustrates that both TNF ligand and its receptors have transmembrane forms and that the extracellular components of those forms can be cleaved to yield soluble 17 kilo-Daltons (kD) TNF ligand and soluble TNF receptors. The bottom panels illustrate TNF reverse signaling (left), conventional soluble ligand-transmembrane receptor signaling (middle), and potential direct cell-to-cell TNF signaling with intracellular signaling occurring in both cells (right).

Soluble 17 kD TNF can signal via the trans-membrane TNF receptors (Rs), (Figure 2, bottom center) as evidenced by the multiple effects induced by injection of soluble 17 kD TNF into the brain including excess sleep. In addition, trans-membrane 26 kD TNF can complex with the soluble TNFRs to induce intracellular pathways within the cell expressing the transmembrane TNF (Figure 2, left lower panel). The extent of the occurrence of this mechanism in the brain is not known although TNF reverse signaling is described in axonal physiology [40]. Another potential TNF signaling mechanism is direct cell-to-cell contact with the transmembrane TNF binding to the transmembrane R with subsequent intracellular signaling occurring in both cells. Whether this mechanism occurs in brain is unknown (Figure 2, lower right) although TNF-mediated direct cell-to-cell contact appears to be important in embryonic stem cell differentiation [41].

Cellular responses to TNF signaling can vary broadly based on variability in R expression and adaptor proteins present in the target cell. There are two membrane-bound TNF Rs, a 55 kD R and a 75 kD R. Neither R has intrinsic enzymatic activity, instead signal through recruitment of adaptor proteins. The TNF R super family is divided into 2 broad categories, according to the adaptor proteins that are recruited upon binding of a ligand [32–36]. Both the 55 kD and 75 kD TNFRs form trimeric complexes with TNF [36]. The specific R type, adaptor protein, and spatial orientation of R-ligand formations dictate target response, which can range from induction of cell death to protection from cell death [32].

The level of expression of TNF in the brain is activity-dependent. When murine facial whiskers are repeatedly stimulated, neuronal production of the trans-membrane 26 kD TNF increases in the somatosensory cortex [37]. Optogenetic stimulation of neurons in vitro enhances expression of neuronal TNF [42]. The induction of neuronal production of TNF by cell activity suggests that TNF plays a role in neuronal connectivity. TNF has a well-established role in synaptic scaling [18]. TNF potentiates AMPA-induced potentials at the post-synaptic membrane [43], and also acts to increase Ca++ conductance via AMPA-induced [44] and voltage-dependent mechanisms [45, 46]. Additionally, TNF modulates glutamatergic transmission [16, 44, 45]. TNF promotes neuronal expression of Homer1a mRNA [47]. Homer1a plays a role in synaptic physiology and is increased after sleep deprivation [48, 49].

TNF in sleep regulation; animal studies

A sleep regulatory substance should be able to satisfy several basic criteria [50–52]. In animal studies, a sleep regulatory substance should enhance a sleep phenotype, such as duration of non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREMS). Inhibition or reduction of the substance should reduce the sleep phenotype. The levels of the purported sleep regulatory substance measured in the brain should correlate with the duration of sleep loss and sleep propensity. Additionally, the sleep regulatory substance should act within known sleep regulatory circuitry and/or induce sleep-like states within local circuits (see below).

The somnogenic actions of TNF in rabbits were first demonstrated in 1987 [53]. Since then, TNF has been shown to promote NREMS duration in every species tested: rats [54], mice [55], and sheep [56]. The effects on NREMS are profound. For instance, when mice are given 3 μg of TNF via intraperitoneal injection, they spend around 90 min longer in NREMS during the first 9 h post-treatment [55]. Additionally, δ power during NREMS also increases after TNF injection (ibid). Δ power amplitude is a sleep phenotype that under normal conditions is indicative of sleep intensity [57]. TNF administration also exerts an effect on rapid eye movement sleep (REMS). While lower doses of TNF are sufficient to promote NREMS, REM sleep is not affected by lower doses of TNF. However, at higher doses of TNF, REMS is inhibited [58]. Interestingly, absence of the 55 kD TNFR in mice is associated with a reduction of REMS duration [55].

While administration of TNF promotes NREMS, inhibiting TNF reduces spontaneous NREMS. NREMS is reduced whether TNF is inhibited by anti-TNF antibodies [59], the soluble TNFR [60], or fragments of the soluble TNFR [61]. The physiologic utility of TNF inhibition is not fully understood. Preliminary data from our lab (unpublished) suggests that treatment of neuronal/glial co-cultures with a soluble TNFR promotes a wake-like state suggesting possible TNF reverse signaling (see Figure 2). Furthermore, if animal subjects are given TNF inhibitors before sleep deprivation, the animals have less sleep rebound than corresponding controls [62]. Substances that modulate TNF production, either directly or indirectly inhibiting its production, inhibit NREMS. For example, IL4, IL10, and IL13 all inhibit NREMS [8]. NREMS increases induced by acute mild increases in environmental temperature are also inhibited when TNF is inhibited [61].

Mice with the 55 kD TNFR knockout sleep less than control mice. Specifically, TNFR knockout mice have less NREMS and REMS than control mice [55], suggesting that TNF has a role in normal sleep physiology, influencing normal sleep times. When these mice are given soluble 17 kD TNF, they do not respond with an increase in NREMS as occurs in control mice (ibid), supporting the concept that TNF as a sleep-promoting substance is acting through the TNFR. Mice lacking both TNFRs also have less spontaneous NREMS than controls [63].

Brain levels of TNF or TNF mRNA correlate with sleep propensity. Within the hypothalamus, concentrations of TNF [64] and TNF mRNA [65–67] fluctuate diurnally. These levels are highest at day break, correlating with the beginning of the rat sleep period. The concentration of TNF protein from trough to peak varies by about a factor of 10. TNF mRNA concentrations double during this same time frame, indicating the presence of post-transcriptional upregulation of TNF underlying this process. TNF levels are also influenced by sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation increases hypothalamic TNF mRNA concentration. Sleep deprivation also increases expression of 55 kD TNFR mRNA [67]. Expression of TNF in the brain can be influenced by multiple factors, such as inflammation, and these conditions are also affected by sleep loss and REMS deprivation [68–72].

TNF microinjection into brain regions associated with sleep and alertness regulation, including the hypothalamic pre-optic area and the locus coeruleus, enhances sleep [74, 75]. In contrast, inhibition of TNF via injection of soluble TNFRs into the hypothalamus inhibits spontaneous NREMS [74]. When TNF is administered locally into the subarachnoid space inferior to the basal surface of the forebrain via micro infusion, NREMS is enhanced and REMS is inhibited [58]. Furthermore, unilateral application of TNF within the somatosensory cortex induces unilateral changes in state-dependent EEG δ wave power [76, 77]. Conversely, unilateral inhibition of TNF via soluble TNFRs reduces EEG δ wave power measured in NREMS [76, 77]. When a TNF short interfering RNA is applied unilaterally to the surface of the somatosensory cortex, expression of TNF is reduced. Further, this treatment lowers EEG δ wave power during NREMS, but there is little reduction of TNF δ wave power during wake or REMS periods [78].

In summary, research over the past 25 years has comprehensively qualified TNF as a key sleep regulatory molecule, using the widely accepted criteria for sleep regulators [50, 51]. However, TNF animal sleep work is limited because almost all of it was conducted using young healthy mice or rats. In contrast, most human studies of sleep and TNF involve patients with chronic pathologies associated with high levels of TNF. Regardless, the measurement of TNF in human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid has been possible for many years. This has led to many correlative studies linking TNF to sleep, cognition, and other brain functions.

Linking TNF to human sleep

TNF blood levels correlate with EEG δ power during spontaneous sleep in humans [79]. During sleep in healthy young men, serum TNF levels decrease [80]; this finding is consistent with the reduction of brain TNF across the rat daytime sleep period [64]. After sleep deprivation in humans, circulating levels of the 55 kD soluble TNFR, but not the 75 kD soluble TNFR, increase [81, 82]. The soluble 55 kD R is a component of normal cerebrospinal fluid [83]. The TNF system may play a role in normal diurnal temperature regulation as well [82]. In healthy volunteers, intravenous injection of endotoxin increases plasma levels of TNF and the soluble 55 kD TNFR and promotes sleep simultaneously [84]. TNF induces fatigue in patients with metastatic cancer [85]. Further, women with breast cancer experience increases of fatigue and TNF levels during chemotherapy [86]. In pediatric obstructive sleep apnea patients, TNF levels increase, and are tightly related to sleepiness; plasma TNF levels, and sleepiness in these patients decrease after surgery [87] and are also associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms in the TNF gene [88].

The TNF G308A polymorphic variant is associated with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, sleep apnea [ibid, 89–92], heart disease [93], tuberculosis [94], Alzheimer’s disease [95], and peri-portal fibrosis regression of schistosomiasis [96]. Furthermore, this variant has relevance to cognitive resilience after sleep deprivation, healthy volunteers with this variant have impaired psychomotor vigilance performance [97].

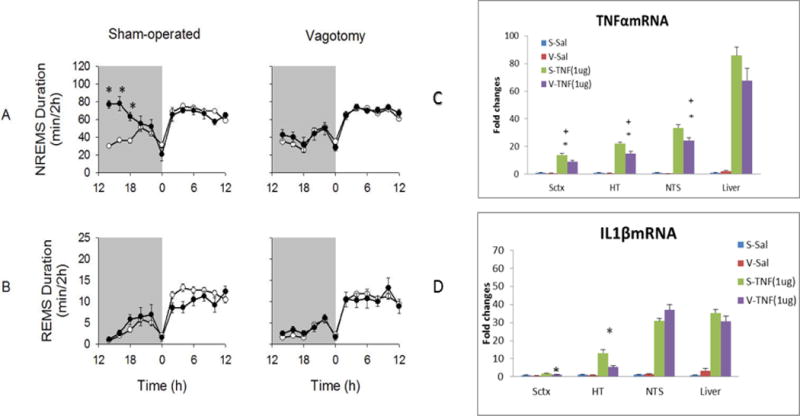

Many human studies involve the measurement of systemic TNF, or associated molecules. How systemic TNF communicates to the brain in humans remains unknown. However, in animals, systemic TNF can induce its own mRNA production in brain via vagus nerve afferents (Figure 3). Vagotomy blocks this action [73]. These results suggest that TNF-induced action potentials in vagal afferents induce TNF and interleukin-1β mRNA expressions in brain. Thus it seems that systemic TNF influences brain production of TNF and other cytokines via the vagus nerve. TNF can also be directly transported from blood to brain [98]. These studies reinforce the experimental measurement of systemic TNF in humans as a means to assess TNF-sleep interactions. However, the nuances of systemic-brain TNF interactions in health and disease remains understudied.

Figure 3.

Vagotomy attenuates the somnogenic actions of systemic soluble tumor necrosis factor α (TNF). TNF, 1 μg give intraperitoneally to mice, enhances non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) for hours. Vagotomy attenuates the effect of this TNF dose on NREMS (A). Rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) durations after TNF were similar to those after saline injections and did not differ between treatment groups (B). (*) = significant differences for 2 hour time bins between vagotomized and sham-operated mice after TNFα injections compared to saline injections. P< 0.05. White circles = saline injection group; dark circles = TNF injection group. The right graphs show that systemic TNF induces brain and liver TNF mRNA and interleukin-1 β (IL1β) mRNA expressions; TNF enhanced its own expression and IL1β expression. These expressions were attenuated in brain after vagotomy. The results provide reassuring evidence that measures of systemic TNF are related to brain functions including sleep. Abbreviations; S-sham operated controls; Sal-saline; Data are derived from reference [73].

There are multiple pathologies associated with excessive soluble 17 kD TNF plasma levels that are also associated with poor sleep, (e.g. fragmentation, reduced duration, loss of normal sleep architecture, sleepiness). These include sleep apnea, insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, chronic fatigue syndrome, cancers, (e.g. gliomas), psoriasis, severe cutaneous lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, severe infectious diseases (e.g. AIDS), post-dialysis fatigue, alcoholism, obesity, Alzheimer disease, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, some autoimmune diseases (e.g. osteoarthritis), preeclampsia, and hyperemesis gravidarum. A variety of TNF inhibitors have been used to treat these diseases and in some of these studies sleep measures were taken. TNF inhibitors generally restore sleep to more normal patterns in these clinical conditions while simultaneously alleviating disease symptoms. The effects of these drugs on sleep in normal people are mostly unknown, thus there remains a gap between human and animal TNF-sleep knowledge. For example, Progranulin (PGRN) is an endogenous glycoprotein with roles in neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration [99]. PGRN is a TNFR ligand acting as a competitive TNF antagonist. PGRN is used for disease therapy [100] including in autoimmune diseases, such as osteoarthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematous, systemic sclerosis, multiple sclerosis and Sjogren’s syndrome [100]. Although PGRN treatment can affect mouse sleep-linked behavior [101], its actions on human sleep remain unstudied. Six additional TNF inhibitors used clinically for which sleep-related evidence are discussed herein.

Sleep/wake effects of prescribed TNF-active substances

Etanercept (ETA)

ETA is a recombinant TNFR protein that binds TNF thereby reducing the effects of naturally present TNF [102]. It is not known if ETA can bind to the 26 kD trans-membrane form of TNF to reverse signal (see above), thus interpretation of clinical studies is speculative. Nevertheless, because TNF is a key inflammatory regulator, ETA is used to treat autoimmune diseases [103]. ETA was the first FDA approved medicine for rheumatoid arthritis and polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [104]. ETA affects sleep. For instance, ETA improves sleep efficiency, total sleep time, and stage 2 sleep duration in rheumatoid arthritis patients [105] and ETA alleviates daytime sleepiness in rheumatoid arthritis patients [106]. In another study, after 36 weeks of ETA-treatment, sleep improved inpatients with moderately active rheumatoid arthritis [107]. Similar results were obtained from psoriasis patients. Most psoriasis patients have disrupted sleep. ETA-treatment for 12 and 24 weeks improved their impaired sleep [108]. ETA also improves the sleep problems associate with ankylosing spondylitis patients [109]. In addition, ETA relieves objective sleepiness in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea [110]. Finally, ETA reduces the REMS in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients; excessive REMS is associated with alcohol relapse [111].

Adalimumab (ADA)

ADA is an anti-recombinant human TNF monoclonal antibody capable of blocking TNF inflammatory activity [112]. It is approved for treatment of a number of autoimmune diseases [113]. For example, the sleep disturbances associated with rheumatoid arthritis [106] are improved with ADA treatment [114]. In psoriasis patients, ADA treatment improved sleep quality [115]. Fatigue and sleep problems also occur in ankylosing spondylitis patients [116]. ADA improves overall sleep and sleep quality in these patients [117].

Certolizumab pegol (CZP)

CZP is a pegylated fragment of an anti-recombinant human TNF monoclonal antibody [118]. CZP is used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn’s disease etc. [119]. In a clinical trial of axial spondylo arthritis, CZP improved sleep in the CAP-recipient patients but not in those receiving placebo [120].

Golimumab (GLM)

GLM is an anti-human monoclonal TNF antibody that has recently been approved for clinical use [121]. GLM binds to both the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNF [30]. In active ankylosing spondylitis patients, GLM treatment led to significant improvements of sleep as determined by Jenkins Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire [109, 122, 123].

Infliximab (IFX)

IFX is a chimeric anti-human TNF monoclonal antibody [124] use to treat autoimmune diseases [125]. In rheumatoid arthritis patients, IFX lowers circulating TNF levels and improves sleep [126]. IFX also relieves daytime sleepiness in rheumatoid arthritis patients [106]. In ankylosing spondylitis patients, IFX improves sleep [109].

Thalidomide (TH)

TH is an immunomodulatory drug that inhibits TNF expression [127]. The current primary clinical uses of TH are for multiple myeloma and erythema nodosum leprosum [128]. TH treatment of severe cutaneous lupus patients induces drowsiness as a common side effects [129] and it reduces serum TNF levels in systemic lupus erythematosus patients [130]. Using TH as the last option of therapy in advanced glioma patients, the patient’s sleep improved [131]. In a separate study, glioma patients were demonstrated to have high TNF serum levels [132]. In Chron’s disease patients, the cessation of TH treatment caused intractable insomnia [133]. Historically, TH was used to relieve morning sickness in pregnancy [134] but the discovery that TH is teratogenic ended this use [135]. Regardless, TH increased REMS and NREMS (stages 3 and 4) in humans but decreased time in stage 1 NREMS [136].

TNF may also be involved in mental disease. In bipolar disorder patients, serum TNF levels are enhanced during manic and depressive episodes [137] and are positively correlated with inhibitory control [138]. In schizophrenia patients, TNF appears to be a trait marker, as levels remained elevated in acute exacerbations and also during subsequent antipsychotic treatment [139]. There is extensive literature indicating that major depressive disorder is associated with elevated plasma levels of TNF. TNF antagonists (IFX, ADA, and ETA) mitigate depressive symptoms and improve associated cognitive deficits [140]. Although these mental diseases are associated with sleep disturbances, clinical outcomes following TNF inhibitor treatment remains understudied.

TNF sleep biology within the context of brain organization of sleep

Despite millions of human stroke cases and many animal brain lesion studies, if the subject survived, sleep always ensues. Although post-lesion sleep may not have normal structure with oscillations between NREMS and REMS and periodic awaking, sometimes duration of sleep recovers [141–143]. This strongly suggests that no specific circuit is required for sleep and that sleep has self-organizing properties in any viable brain tissue that remains after lesions. Further, several marine mammalian and bird species have unihemispheric sleep [144–146] suggesting that in normal animals half of the brain can be asleep. There are also many disassociated state pathologies suggesting that humans can be awake and asleep simultaneously [147]. For instance, during sleep walking the individual is awake to the extent that they can navigate while walking yet asleep in that there responsiveness to some environmental stimuli is reduced. These findings collectively suggest that sleep can be confined to local areas of the brain. Thus, a bottom-up, local use-dependent sleep regulatory mechanism was proposed [148].

Strong experimental evidence indicates that sleep is a fundamental property of small neuronal/glial networks originates from the findings that individual cortical columns oscillate between sleep-like state and wake-like states [7, 76, 149]. In intact animals, evoked response potentials (ERPs) are greater in magnitude during sleep than during waking. Using an electrode array placed over somatosensory, or auditory cortex, electrical activity of individual cortical columns including ERPs could be isolated after sensory stimulation (either facial whisker twitching or auditor sounds). When the experimental rats were asleep then given a sensory stimuli most, but not all, of the cortical columns were in a sleep-like state, as determined from ERP amplitudes. In contrast, when the rat was awake, ERP magnitude was lower. Further, the longer the column was in a wake-like state the higher the probability it would enter into a sleep like state. In addition, the occurrence of the sleep-like state was activity-dependent in that if facial whiskers were repeatedly stimulated the probability of a column entering the sleep-like state increased. When rats were trained to lick a sweet solution in response to a specific whisker stimulation, if the specific cortical column to which afferent nerve fibers projected to from the stimulated whisker was in a wake-like state, the animal did not make mistakes. In contrast, if the specific cortical column was in the sleep-like state (the whole rat was awake), the rat made errors of commission or omission [7]. Finally, if TNF is applied locally to the cortical column, ERP magnitude is enhanced suggesting that TNF induced a sleep like state in the column [37]. Collectively, these data indicate that individual cortical columns oscillate between sleep- and wake-like states and that TNF drives columns into the sleep-like state.

A logical extension of the local use-dependent sleep hypothesis is that any viable neuronal/glial network, whether in vivo or in vitro should exhibit sleep- and wake-like states, as long as connectivity is intact. Co-cultures of dispersed neurons and glia spontaneously display a sleep-like default state as determined by the burstiness of neuron action potentials, and a reversal to a more wake-like state following treatment with excitatory neurotransmitters or amino acids, or electrical stimulation [42, 150, 151]. The culture’s sleep-like state develops over the course of about 10 days as neurons make connections to each other and emergent network properties become manifest. Further, following prolonged electrical stimulation (30 min), the cultures exhibit a rebound in the sleep-like state the next day suggesting sleep homeostasis. Optogenetic stimulation (30 min) induces TNF neuronal expression in the cultures [42]. Finally, if TNF is added to the cultures they appear to be in a deeper sleep-like state as synchrony of electrical potentials and amplitudes of delta waves (0.5–3.5 Hz) increase [42]. These measurements are also used to characterize NREMS in intact animals including humans. One interpretation of these studies is that reduced small networks in culture not only exhibit sleep states, but mechanistically activity-dependent TNF is involved in eliciting the sleep-like state. As Figure 2 suggests, TNF signaling includes reverse signaling. Our preliminary data hint that addition of the soluble TNFR induces a wake-like state in cultures of neurons and glia derived from mice that lack both TNFRs (unpublished).

There is a rich history linking sleep to brain plasticity (e.g. see Behavioral Brain Research Vol 69:1995 special issue). Brain connectivity theories of sleep function were derived from the learning and memory, computer, and physiological literatures [152–155] and logic considerations [148, 156, 157]. Assuming that simple percepts or memory recalls are an emergent property of dynamic synaptic activation patterns, then logically the brain is confronted with several challenges that may be dealt with in part by sleep. New synapses or enhanced synaptic efficacies are needed to form and consolidate new synaptic activation patterns, thus new memories. There is much evidence that sleep is involved in this process [155]. Further, there is a need to preserve established synaptic networks that have already proved adaptive, as evidenced by the animal being alive, and to preserve synaptic plasticity as well [148, 157]. Finally, because synapses and synaptic efficacies are activity-dependent, and there is always massive brain activity, logically there may be a need for synaptic pruning or synaptic down-scaling [153, 156]. All of these potential plasticity issues require a mechanism to label synapses for preservation, greater efficacy, or pruning; if that mechanism is linked to sleep it will provide strong support for a plasticity function for sleep.

Regardless, brain plasticity has long been recognized as being driven by neuron and glia activity-dependent expression of molecules and thus being initiated within local networks. The recognition of sleep as a local use-dependent process was more recent [7, 148, 158]. As local use-dependent processes, the underlying molecular mechanisms link sleep and plasticity regulations. All well-characterized sleep regulatory substances also affect brain plasticity.

Conclusion

There is ample evidence from animals and humans that TNF is involved in sleep regulation. TNF biology and TNF sleep mechanisms reveal much about sleep regulation, the minimal amount of tissue required for sleep, and sleep function. Local application of TNF to small circuits, such as cortical columns or to co-cultures of neurons and glia induces sleep-like states. The in vivo and in vitro sleep-likes states suggest that sleep is a fundamental property of very small circuits. TNF is expressed in neurons as a consequence of neuronal activity. TNF also has a role in brain plasticity, perhaps best known are its roles in synaptic scaling and glutamate receptor (AMPA) trafficking. Both sleep and plasticity are activity-dependent and thus sleep and plasticity mechanisms are linked, and at least via TNF seem inseparable from each other. This is strong evidence for a connectivity function for sleep.

Practice Points.

Patients with pathologies associated with high systemic TNF levels likely also exhibit sleep abnormalities, e.g. fragmented sleep.

Systemic TNF induces brain production of sleep-altering cytokines.

Normalization of excessive systemic TNF improves sleep.

Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines influence physiological sleep and sleep responses to pathological insult.

Research Agenda.

The human sleep consequences of acute vs chronic changes in TNF need to be defined.

How does TNF signaling vary in acute versus chronic exposures?

The effects of chronic TNF elevation in animals on their sleep needs to be characterized.

What role does TNF play in adaptive brain responses to sleep/wake schedules?

Characterization of TNF communication between brain and systemic pools.

TNF signaling, e.g. direct cell-to-cell TNF-mediated contact and signaling, requires study.

The cytokine orchestra in terms of positive and negative feedback mechanisms in brain and systemic tissues and its role in sleep regulation requires further study.

How does TNF NREMS improve peripheral immune responses?

Is local sleep a response to reduce local inflammation from column activation?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to JMK from The National Institutes of Health (USA), grant numbers NS025378, NS096250 and HD36520 and HL123331 to both JMK and SCV

Abbreviations

- ADA

adalimumab

- CZP

certolizumab pegol

- D

Dalton

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- ERP

evoked response potential

- ETA

etanercept

- GLM

golimumab

- IFX

infliximab

- kD

kilo-Dalton

- NREMS

non-rapid eye movement sleep

- PGRN

progranulin

- R

receptor

- REMS

rapid eye movement sleep

- TH

thalidomide

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Glossary of Terms

- Evoked response potential

The extracellular localized electrical response of the brain to an afferent input. ERPs can also be obtained from co-cultures of cells grown in vitro in response to a stimulus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Humoral mechanisms of sleep. In: Parmeggiani PL, Velluti R, editors. The Physiological Nature of Sleep. Imperial College Press; London: 2005. pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borbely AA. Processes underlying sleep regulation. Hormone Res. 1998;49:114–7. doi: 10.1159/000023156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang ZL, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. The role of adenosine in the regulation of sleep. Current Topics in Med Chem. 2011;11:1047–57. doi: 10.2174/156802611795347654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang ZL, Zhang Z, Qu WM. Roles of adenosine and its receptors in sleep-wake regulation. International Rev Neurobiol. 2014;119:349–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801022-8.00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias-Carrion O, Huitron-Resendiz S, Arankowsky-Sandoval G, Murillo-Rodriguez E. Biochemical modulation of the sleep-wake cycle: endogenous sleep-inducing factors. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:1143–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheth S, Brito R, Mukherjea D, Rybak LP, Ramkumar V. Adenosine receptors: expression, function and regulation. International J Mol Sci. 2014;15:2024–52. doi: 10.3390/ijms15022024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Krueger JM, Huang YH, Rector DM, Buysse DJ. Sleep: a synchrony of cell activity-driven small network states. European J Neurosci. 2013;38:2199–209. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger JM, Rector DM, Roy S, Van Dongen HPA, Belenky G, Panksepp J. Sleep as a fundamental property of neuronal assemblies. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:910–19. doi: 10.1038/nrn2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krueger JM, Rector DM, Churchill L. Sleep and cytokines. Sleep Med Clinics. 2007;2:161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luppi PH. Neurochemical aspects of sleep regulation with specific focus on slow-wave sleep. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(Suppl 1):4–8. doi: 10.3109/15622971003637611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and arousal. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2008;1129:275–86. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingiosi AM, Opp MR, Krueger JM. Sleep and immune function: glial contributions and consequences of aging. Current Opinion Neurobiol. 2013;23:806–11. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank MG. Astroglial regulation of sleep homeostasis. Current Opinion Neurobiol. 2013;23:812–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petit JM, Magistretti PJ. Regulation of neuron-astrocyte metabolic coupling across the sleep-wake cycle. Neurosci. 2016;323:135–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell J, Ding F, Nedergaard M. Distinct functional states of astrocytes during sleep and wakefulness: Is norepinephrine the master regulator? Current Sleep Med Reports. 2015;1:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40675-014-0004-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santello M, Bezzi P, Volterra A. TNFalpha controls glutamatergic gliotransmission in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2011;69:988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo M, Lin V, Davis W, Huang T, Carranza A, Sprague S, et al. Preischemic induction of TNF-alpha by physical exercise reduces blood-brain barrier dysfunction in stroke. J Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2008;28:1422–30. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrigiano GG. The self-tuning neuron: synaptic scaling of excitatory synapses. Cell. 2008;135:422–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breder CD, Tsujimoto M, Terano Y, Scott DW, Saper CB. Distribution and characterization of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-like immunoreactivity in the murine central nervous system. J Comp Neurology. 1993;337:543–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.903370403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boka G, Anglade P, Wallach D, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Immunocytochemical analysis of tumor necrosis factor and its receptors in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1994;172:151–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng B, Christakos S, Mattson MP. Tumor necrosis factors protect neurons against metabolic-excitotoxic insults and promote maintenance of calcium homeostasis. Neuron. 1994;12:139–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botchkina GI, Meistrell ME, 3rd, Botchkina IL, Tracey KJ. Expression of TNF and TNF receptors (p55 and p75) in the rat brain after focal cerebral ischemia. Mol Med. 1997;3:765–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibata M. Hypothalamic neuronal responses to cytokines. Yale J Biol and Med. 1990;63:147–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saper CB, Breder CD. Endogenous pyrogens in the CNS: role in the febrile response. Prog Brain Res. 1992;93:419–28. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plata-Salaman CR. Central nervous system mechanisms contributing to the cachexia-anorexia syndrome. Nutrition. 2000;16:1009–12. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Immune modulation of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis. Brain Beh Immun. 2011;25:181–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merrill JE. Tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1 and related cytokines in brain development: normal and pathological. Developmental Neurosci. 1992;14:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000111642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy MK, Tansey MG. TNF signaling inhibition in the CNS: implications for normal brain function and neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflamma. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor JJ. Targeting tumour necrosis factor-alpha in hypoxia and synaptic signalling. Irish J Med Sci. 2013;182:157–62. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-0911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horiuchi T, Mitoma H, Harashima S, Tsukamoto H, Shimoda T. Transmembrane TNF-alpha: structure, function and interaction with anti-TNF agents. Rheumatology. 2010;49:1215–28. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kriegler M, Perez C, DeFay K, Albert I, Lu SD. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell. 1988;53:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ledgerwood EC, Pober JS, Bradley JR. Recent advances in the molecular basis of TNF signal transduction. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1041–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goeddel DV. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor: the Parker B. Francis Lectureship. Chest. 1999;116:69S–73S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.69s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyriakis JM. Activation of the AP-1 transcription factor by inflammatory cytokines of the TNF family. Gene Expression. 1999;7:217–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallach D, Varfolomeev EE, Malinin NL, Goltsev YV, Kovalenko AV, Boldin MP. Tumor necrosis factor receptor and Fas signaling mechanisms. Ann Rev Immun. 1999;17:331–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue J, Ishida T, Tsukamoto N, Kobayashi N, Naito A, Azuma S, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) family: adapter proteins that mediate cytokine signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254:14–24. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churchill L, Rector DM, Yasuda K, Fix C, Rojas MJ, Yasuda T, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: activity dependent expression and promotion of cortical column sleep in rats. Neurosci. 2008;156:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borst SE, Conover CF. High-fat diet induces increased tissue expression of TNF-alpha. Life Sci. 2005;77:2156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spriggs DR, Deutsch S, Kufe DW. Genomic structure, induction, and production of TNF-alpha. Immuno series. 1992;56:3–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kisiswa L, Osorio C, Erice C, Vizard T, Wyatt S, Davies AM. TNFalpha reverse signaling promotes sympathetic axon growth and target innervation. Nature Neurosci. 2013;16:865–73. doi: 10.1038/nn.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohchi C, Tanabe Y, Noguchi K, Mizuno D, Soma G. Induction of differentiation in embryonic stem cells by 26-kD membrane-bound tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and 17-kD free TNF. In Vivo. 1996;10:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Jewett KA, Taishi P, Sengupta P, Roy S, Davis CJ, Krueger JM. Tumor necrosis factor enhances the sleep-like state and electrical stimulation induces a wake-like state in co-cultures of neurons and glia. European J Neurosci. 2015;42:2078–90. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beattie EC, Stellwagen D, Morishita W, Bresnahan JC, Ha BK, Von Zastrow M, et al. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFalpha. Science. 2002;295:2282–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De A, Krueger JM, Simasko SM. Tumor necrosis factor alpha increases cytosolic calcium responses to AMPA and KCl in primary cultures of rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2003;981:133–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furukawa K, Mattson MP. The transcription factor NF-kappaB mediates increases in calcium currents and decreases in NMDA- and AMPA/kainate-induced currents induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1876–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karrer M, Lopez MA, Meier D, Mikhail C, Ogunshola OO, Muller AF, et al. Cytokine-induced sleep: Neurons respond to TNF with production of chemokines and increased expression of Homer1a in vitro. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;47:186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson SE, Duricka DL, Campbell K, Churchill L, Krueger JM. Homer1a and 1bc levels in the rat somatosensory cortex vary with the time of day and sleep loss. Neurosci Lett. 2004;367:105–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maret S, Dorsaz S, Gurcel L, Pradervand S, Petit B, Pfister C, et al. Homer1a is a core brain molecular correlate of sleep loss. Proc Nat Acad Sci (USA) 2007;104:20090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710131104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borbely AA, Tobler I. Endogenous sleep-promoting substances and sleep regulation. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:605–70. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoué S. Biology of sleep substances. CRC Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krueger JM, Fang J, Taishi P, Chen Z, Kushikata T, Sleep Gardi J. A physiologic role for IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1998;856:148–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shoham S, Davenne D, Cady AB, Dinarello CA, Krueger JM. Recombinant tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 enhance slow-wave sleep. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:R142–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.1.R142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nistico G, DeSarro G, Rotiroti D. Behavioral and electrocortical spectrum power changes of interleukins and tumor necrosis factor after microinjection into different areas of the brain. In: Smirne S, Franceschi M, Ferini-Strambi, Zucconi M, editors. Sleep, Hormones and Immunological System. Masson; 1992. pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang J, Wang Y, Krueger JM. Mice lacking the TNF 55 kDa receptor fail to sleep more after TNFalpha treatment. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5949–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05949.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickstein JB, Moldofsky H, Lue FA, Hay JB. Intracerebroventricular injection of TNF-alpha promotes sleep and is recovered in cervical lymph. Am J Physio. 1999;276:R1018–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.4.R1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis CJ, Clinton JM, Jewett KA, Zielinski MR, Krueger JM. Delta wave power: an independent sleep phenotype or epiphenomenon? J Clinical Sleep Med. 2011;7:S16–8. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terao A, Matsumura H, Yoneda H, Saito M. Enhancement of slow-wave sleep by tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by cyclooxygenase-2 in rats. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3791–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi S, Kapas L, Fang J, Krueger JM. An anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody suppresses sleep in rats and rabbits. Brain Res. 1995;690:241–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00609-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi S, Tooley DD, Kapas L, Fang J, Seyer JM, Krueger JM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor in the brain suppresses rabbit sleep. Pflugers Archiv: European J of Physiol. 1995;431:155–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00410186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi S, Krueger JM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor prevents warming-induced sleep responses in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1325–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.4.R1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takahashi S, Kapas L, Seyer JM, Wang Y, Krueger JM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor attenuates physiological sleep in rabbits. Neuroreport. 1996;7:642–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199601310-00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kapas L, Bohnet SG, Traynor TR, Majde JA, Szentirmai E, Magrath P, et al. Spontaneous and influenza virus-induced sleep are altered in TNF-alpha double-receptor deficient mice. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1187–98. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90388.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Floyd RA, Krueger JM. Diurnal variation of TNF alpha in the rat brain. Neuroreport. 1997;8:915–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bredow S, Guha-Thakurta N, Taishi P, Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Diurnal variations of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA and alpha-tubulin mRNA in rat brain. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997;4:84–90. doi: 10.1159/000097325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veasey S, Mackiewicz M, Fenik P, Ro M, Oglivie M, Pack A. IL1 beta knockout mice lack the TNF alpha response to sleep deprivation but have normal sleep and sleep recovery. Soc Neurosci Abst. 1997;23:792. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taishi P, Gardi J, Chen Z, Fang J, Krueger J. Sleep deprivation increases the expression of TNF alpha mRNA and TNF 55kD receptor mRNA in rat brain. The Physiologist. 1999;42:A4. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Venancio DP, Suchecki D. Prolonged REM sleep restriction induces metabolic syndrome-related changes: mediation by pro-inflammatory cytokines. Brain Beh Immun. 2015;47:109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chennaoui M, Gomez-Merino D, Drogou C, Geoffroy H, Dispersyn G, Langrume C, et al. Effects of exercise on brain and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers induced by total sleep deprivation in rats. J Inflamma. 2015;12:56. doi: 10.1186/s12950-015-0102-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramesh V, Nair D, Zhang SX, Hakim F, Kaushal N, Kayali F, et al. Disrupted sleep without sleep curtailment induces sleepiness and cognitive dysfunction via the tumor necrosis factor-α pathway. J Neuroinflamma. 2012;9:91. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ashley NT, Sams DW, Brown AC, Dumaine JE. Novel environment influences the effect of paradoxical sleep deprivation upon brain and peripheral cytokine gene expression. Neurosci Lett. 2016;615:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cathomas F, Fuertig R, Sigrist H, Newman GN, Hoop V, Bizzozzero M, et al. CD40-TNF activation in mice induces extended sickness behavior syndrome co-incident with but not dependent on activation of the kynurenine pathway. Brain Beh Immun. 2015;50:125–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zielinski MR, Dunbrasky DL, Taishi P, Souza G, Krueger JM. Vagotomy attenuates brain cytokines and sleep induced by peripherally administered tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lipopolysaccharide in mice. Sleep. 2013;36:1227–38. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kubota T, Li N, Guan Z, Brown RA, Krueger JM. Intrapreoptic microinjection of TNF-α enhances non-REM sleep in rats. Brain Res. 2002;932:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.De Sarro G, Gareri P, Sinopoli VA, David E, Rotiroti D. Comparative, behavioural and electrocortical effects of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 microinjected into the locus coeruleus of rat. Life Sci. 1997;60:555–64. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rector DM, Schei JL, Van Dongen H, Belenky G, Krueger JM. Physiological markers of local sleep. European J Neurosci. 2009;29:1771–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoshida H, Peterfi Z, García-García F, Kirkpatrick R, Yasuda T, Krueger JM. State-specific asymmetries in EEG slow wave activity induced by local application of TNFα. Brain Res. 2004;1009:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taishi P, Churchill L, Wang M, Kay D, Davis CJ, Guan X, et al. TNFα siRNA reduces brain TNF and EEG delta wave activity in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1156:125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79*.Darko DF, Miller JC, Gallen C, White J, Koziol J, Brown SJ, et al. Sleep electroencephalogram delta-frequency amplitude, night plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Nat Acad Sci (USA) 1995;92:12080–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80*.Dimitrov S, Besedovsky L, Born J, Lange T. Differential acute effects of sleep on spontaneous and stimulated production of tumor necrosis factor in men. Brain Beh Immun. 2015;47:201–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shearer WT, Reuben JM, Mullington JM, Price NJ, Lee BN, Smith EO, et al. Soluble TNF-alpha receptor 1 and IL-6 plasma levels in humans subjected to the sleep deprivation model of spaceflight. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2001;107:165–70. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82*.Haack M, Pollmacher T, Mullington JM. Diurnal and sleep-wake dependent variations of soluble TNF- and IL-2 receptors in healthy volunteers. Brain Beh Immun. 2004;18:361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Puccioni-Sohler M, Rieckmann P, Kitze B, Lange P, Albrecht M, Felgenhauer K. A soluble form of tumour necrosis factor receptor in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy and other neurological diseases. J Neurology. 1995;242:239–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00919597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mullington J, Korth C, Hermann DM, Orth A, Galanos C, Holsboer F, et al. Dose-dependent effects of endotoxin on human sleep. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:R947–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eskander ED, Harvey HA, Givant E, Lipton A. Phase I study combining tumor necrosis factor with interferon-alpha and interleukin-2. Am J Clin Oncology. 1997;20:511–4. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199710000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Raudonis BM, Kelley IH, Rowe N, Ellis J. A pilot study of proinflammatory cytokines and fatigue in women with breast cancer during chemotherapy. Cancer Nursing. 2017;40:323–31. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87*.Gozal D, Serpero LD, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Capdevila OS, Khalyfa A, Tauman R. Sleep measures and morning plasma TNF-alpha levels in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2010;33:319–25. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Khalyfa A, Serpero LD, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Capdevila OS, Gozal D. TNF-α gene polymorphisms and excessive daytime sleepiness in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr. 2011;158:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bielicki P, MacLeod AK, Douglas NJ, Riha RL. Cytokine gene polymorphisms inobstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2015;16:792–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhong A, Xiong X, Xu H, Shi M. An updated meta-analysis of the association between tumor necrosis factor-α -308G/A polymorphism and obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 15;9(9):e106270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu Y, Cao C, Wu Y, Zhang C, Zhu C, Ying S, Chen Z, Shen H, Li W. TNF-α-308G/A polymorphism contributes to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome risk: evidence basedon 10 case-control studies. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 5;9(9):e106183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Almpanidou P, Hadjigeorgiou G, Gourgoulianis K, Papadimitriou A. Associationof tumor necrosis factor-α gene polymorphism (-308) and obstructive sleepapnea-hypopnea syndrome. Hippokratia. 2012 Jul;16(3):217–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Davis CJ, Krueger JM. Sleep and cytokines. Sleep Med Clinics. 2012;7:517–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ceylan E, Karkucak M, Coban H, Karadag M, Yakut T. Evaluation of TNF-alpha gene (G308A) and MBL2 gene codon 54 polymorphisms in Turkish patients with tuberculosis. J Infect and Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang T. TNF-alpha G308A polymorphism and the susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease: an updated meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2015;46:24–30 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oliveira JB, Silva PC, Vasconcelos LM, Gomes AV, Coelho MR, Cahu GG, et al. Influence of polymorphism (-G308A) TNF-alpha on the periportal fibrosis regression of schistosomiasis after specific treatment. Genetic Testing Mol Biomarkers. 2015;19:598–603. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Satterfield BC, Wisor JP, Field SA, Schmidt MA, Van Dongen HP. TNFalpha G308A polymorphism is associated with resilience to sleep deprivation-induced psychomotor vigilance performance impairment in healthy young adults. Brain Beh Immun. 2015;47:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Opp MR, George A, Ringgold KM, Hansen KM, Bullock KM, Banks WA. Sleep fragmentation and sepsis differentially impact blood–brain barrier integrity and transport of tumor necrosis factor-α in aging. Brain Beh Immun. 2015;50:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.De Muynck L, Van Damme P. Cellular effects of progranulin in health and disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45:549–60. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jian J, Li G, Hettinghouse A, Liu C. Progranulin: A key player in autoimmune diseases. Cytokine. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang K, Li YJ, Feng D, Zhang P, Wang YT, Li X, et al. Imbalance between TNFalpha and progranulin contributes to memory impairment and anxiety in sleep-deprived mice. Sci Reports. 2017;7:43594. doi: 10.1038/srep43594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zalevsky J, Secher T, Ezhevsky SA, Janot L, Steed PM, O’Brien C, et al. Dominant-negative inhibitors of soluble TNF attenuate experimental arthritis without suppressing innate immunity to infection. J Immunology. 2007;179:1872–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Crunkhorn S. Autoimmune diseases: New route to targeting TNF. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2011;10:337. doi: 10.1038/nrd3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, VanderStoep A, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:385–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Detert J, Dziurla R, Hoff P, Gaber T, Klaus P, Bastian H, et al. Effects of treatment with etanercept versus methotrexate on sleep quality, fatigue and selected immune parameters in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatology. 2016;34:848–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T. Sleep disturbance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation by medical outcomes study and visual analog sleep scales. J Rheumatology. 2006;33:1942–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pavelka K, Szekanecz Z, Damjanov N, Majdan M, Nasonov E, Mazurov V, et al. Induction of response with etanercept-methotrexate therapy in patients with moderately active rheumatoid arthritis in Central and Eastern Europe in the PRESERVE study. Clin Rheumatology. 2013;32:1275–81. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thaci D, Galimberti R, Amaya-Guerra M, Rosenbach T, Robertson D, Pedersen R, et al. Improvement in aspects of sleep with etanercept and optional adjunctive topical therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from the PRISTINE trial. J European Acad Dermatology and Venereology. 2014;28:900–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Karadag O, Nakas D, Kalyoncu U, Akdogan A, Kiraz S, Ertenli I. Effect of anti-TNF treatment on sleep problems in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology International. 2012;32:1909–13. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1907-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110*.Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Lin HM, Bixler EO, Trakada G, Chrousos GP. Marked decrease in sleepiness in patients with sleep apnea by etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist. J Clin Endo and Meta. 2004;89:4409–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111*.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Valladares EM, Breen EC, Ehlers CL. Tumor necrosis factor antagonism normalizes rapid eye movement sleep in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Burness CB, McKeage K. Adalimumab: A Review in Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Drugs. 2015;75:2119–30. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pecoraro V, De Santis E, Melegari A, Trenti T. The impact of immunogenicity of TNFalpha inhibitors in autoimmune inflammatory disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmunity Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Emara MK, Saadah A, Hassan M, Moussa M, Hourani H. Pattern of obesity and insulin, glucagon, sex hormone binding globulin and lipids in obese Arab women. Diabetes Res. 1989;10:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Strober BE, Sobell JM, Duffin KC, Bao Y, Guerin A, Yang H, et al. Sleep quality and other patient-reported outcomes improve after patients with psoriasis with suboptimal response to other systemic therapies are switched to adalimumab: results from PROGRESS, an open-label Phase IIIB trial. British J Derm. 2012;167:1374–81. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ward MM. Health-related quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis: a survey of 175 patients. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12:247–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rudwaleit M, Gooch K, Michel B, Herold M, Thorner A, Wong R, et al. Adalimumab improves sleep and sleep quality in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatology. 2011;38:79–86. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Acosta-Felquer ML, Rosa J, Soriano ER. An evidence-based review of certolizumab pegol in the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: place in therapy. Open Access Rheumatology: Res Rev. 2016;8:37–44. doi: 10.2147/OARRR.S56837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cauli A, Piga M, Lubrano E, Marchesoni A, Floris A, Mathieu A. New approaches in tumor necrosis factor antagonism for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: Certolizumab Pegol. J Rheumatology Supp. 2015;93:70–2. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sieper J, Kivitz A, van Tubergen A, Deodhar A, Coteur G, Woltering F, et al. Impact of Certolizumab Pegol on patient-reported outcomes in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:1475–80. doi: 10.1002/acr.22594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Harzallah I, Rigaill J, Williet N, Paul S, Roblin X. Golimumab pharmacokinetics in ulcerative colitis: a literature review. Therapeutic Advan Gastroenterology. 2017;10:89–100. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16676194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bao C, Huang F, Khan MA, Fei K, Wu Z, Han C, et al. Safety and efficacy of golimumab in Chinese patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: 1-year results of a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Rheumatology. 2014;53:1654–63. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Inman RD, Davis JC, Jr, Heijde D, Diekman L, Sieper J, Kim SI, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58:3402–12. doi: 10.1002/art.23969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Huerva V, Ascaso FJ, Grzybowski A. Infliximab for peripheral ulcerative keratitis treatment. Medicine. 2014;93:e176. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vaz JL, Fernandes V, Nogueira F, Arnobio A, Levy RA. Infliximab-induced autoantibodies: a multicenter study. Clin Rheumatology. 2016;35:325–32. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zamarron C, Maceiras F, Mera A, Gomez-Reino JJ. Effect of the first infliximab infusion on sleep and alertness in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Annals Rheumatic Diseases. 2004;63:88–90. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Majumder S, Sreedhara SR, Banerjee S, Chatterjee S. TNF alpha signaling beholds thalidomide saga: a review of mechanistic role of TNF-alpha signaling under thalidomide. Current Topics in Med Chem. 2012;12:1456–67. doi: 10.2174/156802612801784443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bramuzzo M, Ventura A, Martelossi S, Lazzerini M. Thalidomide for inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review. Medicine. 2016;95:e4239. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang D, Chen H, Wang S, Zou Y, Li J, Pan J, et al. Thalidomide treatment in cutaneous lesions of systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter study in China. Clin Rheumatology. 2016;35:1521–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lateef A, Petri M. Biologics in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Opinion Rheumatology. 2010;22:504–9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833b475e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hassler MR, Sax C, Flechl B, Ackerl M, Preusser M, Hainfellner JA, et al. Thalidomide as palliative treatment in patients with advanced secondary glioblastoma. Oncology. 2015;88:173–9. doi: 10.1159/000368903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Albulescu R, Codrici E, Popescu ID, Mihai S, Necula LG, Petrescu D, et al. Cytokine patterns in brain tumour progression. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:979748. doi: 10.1155/2013/979748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fox MR, Harris A. Intractable insomnia after cessation of treatment with thalidomide. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1567–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mujagic H, Chabner BA, Mujagic Z. Mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic uses of thalidomide. Croatian Med J. 2002;43:274–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Dimopoulos MA, Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou V. Adverse effects of thalidomide administration in patients with neoplastic diseases. Am J Med. 2004;117:508–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kanbayashi T, Shimizu T, Takahashi Y, Kitajima T, Takahashi K, Saito Y, et al. Thalidomide increases both REM and stage 3–4 sleep in human adults: a preliminary study. Sleep. 1999;22:113–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Brietzke E, Kapczinski F. TNF-alpha as a molecular target in bipolar disorder. Prog Neuro-psychopharm Biol Psychi. 2008;32:1355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Barbosa IG, Rocha NP, Huguet RB, Ferreira RA, Salgado JV, Carvalho LA, et al. Executive dysfunction in euthymic bipolar disorder patients and its association with plasma biomarkers. J Affective Disorders. 2012;137:151–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ribeiro-Santos A, Lucio Teixeira A, Salgado JV. Evidence for an immune role on cognition in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Current Neuropharma. 2014;12:273–80. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1203140511160832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bortolato B, Carvalho AF, Soczynska JK, Perini GI, McIntyre RS. The Involvement of TNF-alpha in cognitive dysfunction associated with major depressive disorder: An opportunity for domain specific treatments. Current Neuropharma. 2015;13:558–76. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150630171433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Shoham S, Blatteis CM, Krueger JM. Effects of preoptic area lesions on muramyl dipeptide-induced sleep and fever. Brain Res. 1989;476:396–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Edgar DM, Dement WC, Fuller CA. Effect of SCN lesions on sleep in squirrel monkeys: evidence for opponent processes in sleep-wake regulation. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1065–79. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01065.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Mendelson WB, Bergmann BM, Tung A. Baseline and post-deprivation recovery sleep in SCN-lesioned rats. Brain Res. 2003;980:185–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mukhametov LM. Unihemispheric slow-wave sleep in the Amazonian dolphin, Inia geoffrensis. Neurosci Lett. 1987;79:128–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Rattenborg NC, Lima SL, Lesku JA. Sleep locally, act globally. The Neuroscientist. 2012;18:533–46. doi: 10.1177/1073858412441086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mascetti GG. Unihemispheric sleep and asymmetrical sleep: behavioral, neurophysiological, and functional perspectives. Nat Sci Sleep. 2016;8:221–38. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S71970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Mahowald MW, Cramer Bornemann MA, Schenck CH. State dissociation, human behavior, and consciousness. Current Topics in Med Chem. 2011;11:2392–402. doi: 10.2174/156802611797470277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Krueger JM, Obal F. A neuronal group theory of sleep function. J Sleep Res. 1993;2:63–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1993.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Rector DM, Topchiy IA, Carter KM, Rojas MJ. Local functional state differences between rat cortical columns. Brain Res. 2005;1047:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Corner MA. Reciprocal homeostatic responses to excitatory synaptic receptor inactivation in developing organotypic cortical networks in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2008;438:300–2. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hinard V, Mikhail C, Pradervand S, Curie T, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J, et al. Key electrophysiological, molecular, and metabolic signatures of sleep and wakefulness revealed in primary cortical cultures. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12506–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2306-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Frank MG. Sleep and plasticity in the visual cortex: more than meets the eye. Current Opinion in Neurobiol. 2017;44:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Some considerations on sleep and neural plasticity. Arch Italiennes de Biologie. 2001;139:221–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155*.Krueger JM, Frank MG, Wisor JP, Roy S. Sleep function: toward elucidating an enigma. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;28:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Crick F, Mitchison G. REM sleep and neural nets. Behavioural Brain Research. 1995;69:147–55. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00006-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kavanau JL. Sleep and dynamic stabilization of neural circuitry: a review and synthesis. Behav Brain Res. 1994;63:111–26. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Krueger JM, Roy S. Sleep’s Kernel: Surprisingly small sections of brain, and even neuronal and glial networks in a dish, display many electrical indicators of sleep. Scientist. 2016;30:36–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]