Abstract

Background

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is among the leading causes of death worldwide. Inhaled pollutants are the prime risk factor, but the pathogenesis and progression of the diseased is poorly understood. Most studies on the disease onset and trajectory have focused on genetic and molecular biomarkers. Here we investigate the role of the airway anatomy and the consequent respiratory fluid mechanics on the development of COPD.

Methods

We segmented CT scans from a five-year longitudinal study in three groups of smokers (18 subjects each) having: (i) minimal/mild obstruction at baseline with declining lung function at year five; (ii) minimal/mild obstruction at baseline with stable function, and (iii) normal and stable lung function over the five year period. We reconstructed the bronchial trees up to the 7th generation, and for one subject in each group we performed MRI velocimetry in 3D printed models.

Findings

The subjects with airflow obstruction at baseline have smaller airway diameters, smaller child-to-parent diameter ratios, larger length-to-diameter ratios, and smaller fractal dimensions. The differences are more significant for subjects that develop severe decline in pulmonary function. The secondary flows that characterize lateral dispersion along the airways are found to be less intense in the subjects with airflow obstruction.

Interpretation

These results indicate that morphology of the conducting airways and inspiratory flow features are correlated with the status and progression of COPD already at an early stage of the disease. This suggests that imaging-based biomarkers may allow a pre-symptomatic diagnosis of disease progression.

Keywords: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, airway morphology, respiratory fluid dynamics

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the U.S. and the only leading cause of death that is increasing in prevalence (Minino et al. 2010). In addition to increased mortality, COPD decreases patients’ quality of life due to shortness of breath and chronic cough, which can progress over years to chronic hypoxemic and/or respiratory failure. Cigarette smoking is the major known risk factor; however, it remains unknown why only 15–20% of those that smoke develop COPD (Fletcher & Peto 1977). In addition, the factors that contribute to this variability in susceptibility remain undetermined. COPD is characterized by progressive airflow limitation that is not fully reversible (Celli et al. 2004). The forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) with respect to the forced vital capacity (FVC, the total amount of air exhaled) both defines and characterizes the severity of the disease (Rabe et al. 2007) and is a well-known predictor of mortality and morbidity. However, FEV1 alone does not correlate well with health status or symptoms (Antonelli-Incalzi et al. 2003). Moreover lung function per se does not accurately predict the short or long-term course of a patient’s condition, and is therefore of limited usefulness when attempting to identify those at risk of disease progression.

The early and preclinical phases of COPD remain fairly undescribed; therefore, biomarkers identifying those at risk of developing COPD would be highly valuable to identify sub-populations most suitable for primary prevention strategies and therapies. Most COPD biomarker studies to date have focused on identifying active disease, especially those prone to exacerbations (Rosenberg & Kalhan 2012). C-Reactive Protein (CRP) has been associated with increased risk of incident COPD (van Durme et al. 2009), but these studies have not translated into clinical practice. The discovery of new markers that correlate with COPD severity and foretell progression would enable clinicians to identify susceptible patients and allow researchers to identify new therapies.

It has long been recognized that a thorough understanding of the relationship between airway structure, airflow, and regional ventilation is important for improving the diagnosis and treatment of lung diseases (Tawhai & Lin 2011). Numerous studies have focused on the relationship between lung structural abnormalities and pulmonary function in COPD, both for phenotyping and to highlight mechanisms contributing to airflow limitations (Hogg 2004). Medical imaging in general, and computed tomography (CT) in particular, are commonly used for diagnosis and assessment of lung disease progression (Hoffman et al. 2006). The anatomical features of the lungs determine the airflow and hence the transport and deposition of the inhaled noxious particles (Darquenne et al. 2011), which in turn may lead to an inflammatory response. However, to our best knowledge, no study to date has considered the role of airway structure and associated flow features in the pathogenesis and progression of COPD.

Here we investigate the possibility that structural and functional airway characteristics may be used as biomarkers to detect subclinical cases and predict disease progression. We use lung CT data to compare structural properties of the bronchial tree in a cohort of subjects with minimal or mild obstruction who later develop rapid FEV1 decline, and compare against subjects with mild and stable obstruction as well as normal subjects. We also consider representative members of each group and investigate the three-dimensional inspiratory flow field. The latter is obtained by in vitro inhalation experiments using phase-contrast MRI in 3D printed replicas of the reconstructed bronchial trees.

Methods

Cohort of subjects

This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1410E54644). Subjects consist of three groups of 18 individuals each, extracted from the database of COPDGene (Regan et al. 2011), a large multicenter longitudinal study that carried out high-quality CT scans and pulmonary function tests of subjects at risk for COPD. COPDGene contains data obtained during a first visit (baseline) as well as a follow up after five years. We selected subjects belonging to three groups:

Group 1 (hereafter named “decliner COPD”): subjects who at baseline showed mild to minimal airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC < 0.7 and FEV1 larger than 80% of the value predicted for their demographic), and who demonstrated large FEV1 decline (0.5 liters or more) after five years.

Group 2 (hereafter named “stable COPD”): subjects with similarly mild airflow limitation at baseline, but minimal to no FEV1 decline after five years.

Group 3 (hereafter named “normal”): subjects with normal FEV1 and stable over the five-year period.

For better consistency, the subjects were matched across the groups in 18 triplets with similar age, gender, and smoking history. Each group includes 9 males and 9 females, and the mean subject age is 57 (ranging from 46 to 72 years old).

Morphometry from CT scans

We examined both inspiratory (maximal inflation) and expiratory (passive exhalation) CT scans. The three-dimensional images were acquired using MDCT (see Regan et al. 2011 for details on the imaging protocol). The image resolution was dependent on both the slice thickness, which ranged from 0.5 to 0.75 mm, and the in-plane pixel size, which was determined by the field of view. The image voxel size was nearly isotropic and had a mean value of 0.3 mm3 (Washko et al. 2014).

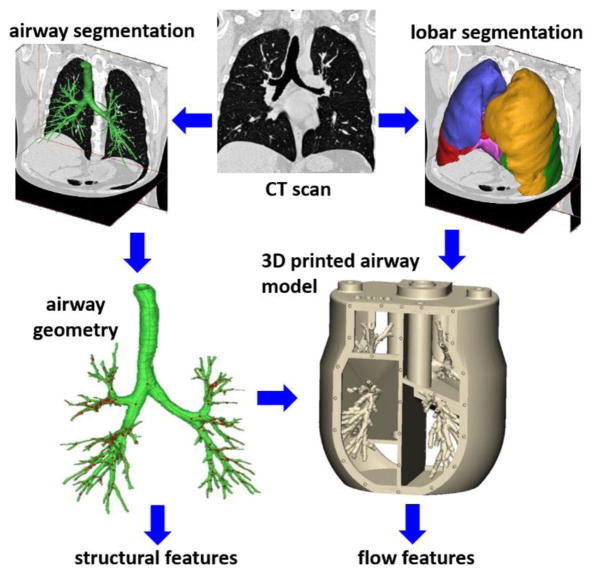

Figure 1 summarizes the process which leads to the extraction of both structural and air flow features (discussed in the present section and in the following one, respectively). The process of extraction and analysis of morphometric features is the same as in Van de Moortele et al. (2017) and is summarized only briefly here. The inspiratory CT scans are segmented and converted to stereolithography files using the software Magics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Airways of diameter larger than about 0.6 mm are identified, allowing to capture most branches down to the 7th generation of bronchial bifurcation. The segmentation process is semi-automatic, was thoroughly verified by visual inspection, and is corroborated by the fact that the number of reconstructed branch at the Nth generations is close to the theoretical value 2N (see Van de Moortele et al. 2017). For each reconstructed branch, we calculate the length L (defined as the distance between successive bifurcation points) and the diameter D (averaged over the central 50% of the branch length). Branching angles were also calculated, although not reported here. Inspiratory and expiratory scans were compared for each subject to assess the lobar ventilation needed to impose appropriate boundary conditions in the MRI flow measurements. For both sets of scans, the five lobes were segmented and separated by identifying fissure lines on the CT images, and the lobar ventilation was established by assessing lobar volume expansion, assuming the tissue volume is conserved (Yin et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the workflow to obtain structural and flow features of the airway tree starting from lung CT scans.

To explore the fractal nature of the bronchial tree (Nelson & Manchester 1988, Glenny & Robertson 2011), we calculated the box-counting dimension db (used in several biological settings including imaging of lung tissues, see Lennon et al. 2015). An isotropic 3D Cartesian grid is superimposed to the segmented bronchial structure and, for a given size Δ of the grid, the number of cubic boxes NB needed to cover the whole structure is counted. We defined the local exponent as the logarithmic slope:

| (1) |

and calculated the box-counting dimension as a fit over the range for which the slope is approximately constant. Such range is larger than two decades for all cases.

Inspiratory flow measurements

For each of the three groups, the airway tree of one representative subject (with morphometric features close to the middle of the group distribution) was used to build a physical model, which was then employed for the MRI flow measurements. We used phase-contrast MRI velocimetry (Pelc et al. 1994, Elkins et Alley 2007, Markl et al. 2012) and the procedure was again similar to that described in Van de Moortele et al. (2017). The internal surface of the airway walls (reconstructed at total lung capacity) is used to generate a solid airway model. The model lumen corresponds to the reconstructed anatomy, while the wall thickness is kept uniform and equal to 2.5 mm. The software 3-Matics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) is used for this process. A five-cavity enclosure was then built around it using the software SolidWorks (Mountain View, CA) creating a one-piece model which was 3D printed in Watershed XC 11122. Each cavity collected the flow from the terminal bronchi of the corresponding lobe, and had separate outlet valves to adjust the respective return flow rates. These were measured with a transonic flow meter and set to match the subject-specific lobar ventilation measured from the lobar segmentation of the inspiratory and expiratory CT scans. The working fluid was water with 0.06 mol/L of copper sulfate, driven by a centrifugal pump through a flow loop consisting of a reservoir, plastic tubing, and a digital flow controller. Since we considered steady inhalation in a rigid geometry, the flow is completely characterized by the Reynolds number, which at the trachea is defined as:

| (2) |

where U0 and D0 are the bulk velocity and the hydraulic diameter at the uppermost reconstructed end of the trachea, and ν is the fluid kinematic viscosity. The flow in a rigid airway model is completely characterized by the Reynolds and Womersley numbers (Jan et al. 1989); in the present case in which steady inhalation is considered, only the former needs to be matched. Therefore, dynamic similarity with air flow is achieved by adjusting the water flow velocity to compensate for its lower kinematic viscosity.

For all cases, we set Re0 = 1750, which is typical of normal breathing conditions (Pedley 1977, Grotberg 2001). A 3 T Siemens scanner was used, with the airway model inserted in a transmit-and-receive radio-frequency coil. Velocity data were obtained with the sequence from Markl. et al. (2012) on a uniform grid at a resolution of 0.6 mm in all directions, and averaged over four successive scans to increase accuracy. The expected uncertainty is calculated following Pelc et al. (1994) to be between 4% and 6% of U0 depending on the case and spatial location. At each point along the airway centerline we defined a normal cross-section and distinguished between axial and secondary velocity components, which are perpendicular and parallel to the cross-section, respectively. We calculated branch-averaged velocities by considering cross-sections spaced by one voxel size over the central 50% of the length of each branch.

Results

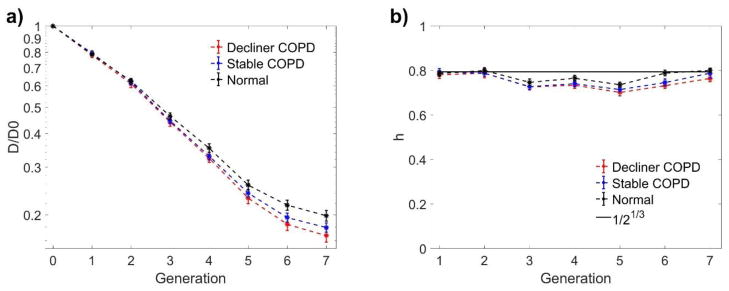

Figure 2a shows the airway diameter (normalized by the value at the trachea D0) as a function of the branching generation for the three groups of subjects. In this, as in the following plots, the error bars represent +/− standard error. Here we use a semi-log plot to highlight the expected exponential decay with branching generation (which would lead to a straight line), resulting from a constant value of the child-to-parent diameter ratio h (West et al. 1986). Indeed, plotting the ratio as a function of generation number (Fig. 2b), for the normal subjects (Group 3) we obtain good agreement with the theoretical value of h = 0.5(1/3) ≈ 0.79 (Weibel 1963), which theoretically minimizes air flow resistance and entropy production (Wilson 1969, West et al. 1997). In comparison, the normalized airway diameters of the stable COPD subjects (Group 2) are noticeably smaller, and so is h. The reduction in diameter (and diameter ratio) is even greater when considering the decliner COPD subjects (Group 1).

Figure 2.

Normalized branch diameter (a) and child-to-parent branch diameter ratio (b) as a function of generation of bifurcation. D/D0 is the normalized diameter normalized by the diameter at the trachea, h is the child-to-parent diameter ratio. Error bars indicate standard error.

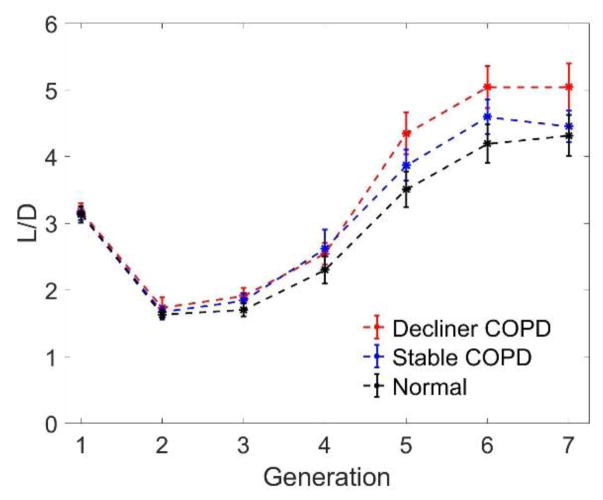

The reduction in diameter shown in Fig. 2 is not associated with a homothetic shrinking of the tree; indeed, the values of the airway lengths are similar in the three groups. It follows that the airway length-to-diameter ratio L/D is sizably higher for the stable COPD subjects, and even more for the decliner COPD subjects (Fig. 3). Compared to the diameter ratio h, the L/D ratio varies much more with the generation number, indicating that the assumption of a self-similar tree is not fully appropriate for the central airways (see Van de Moortele et al. 2017), in either normal or diseased subjects.

Figure 3.

Length-to-diameter ratio (L/D) as a function of generation of bifurcation. Error bars indicate standard error.

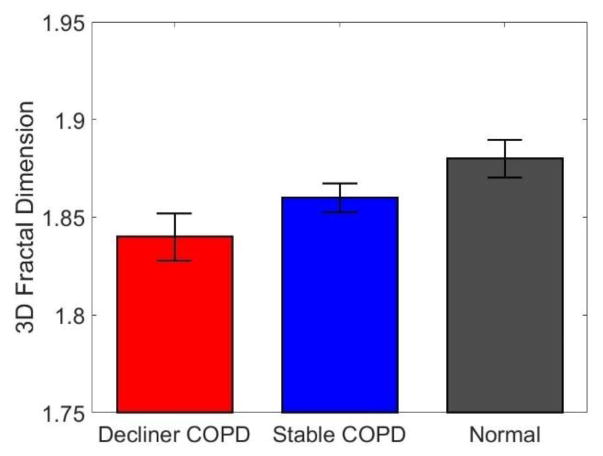

In addition to the airway diameter and length, we analyzed the branching angles but did not find significant differences between the three groups. On the other hand, the fractal dimension obtained via the box-counting method is found to decrease remarkably from normal to stable COPD to decliner COPD (Fig. 4). This indicates that the bronchial trees of the diseased subjects are less tortuous and space-filling compared to the normal subjects (Nelson & Manchester 1998). More details on the fractal nature of the airway tree and its implications are given in Van de Moortele et al. (2017).

Figure 4.

Fractal dimension of the bronchial trees, obtained via box-counting method applied to the reconstructed airway volume. Error bars indicate standard error.

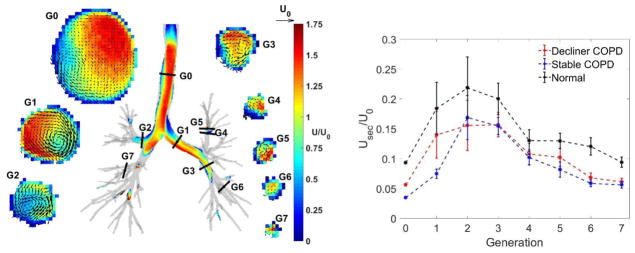

Figure 5 illustrates the inspiratory flow field measured by in vitro MRI velocimetry and demonstrates the secondary flow strength normalized by U0. For all subjects, the secondary flows build up in the first few bifurcations and then steadily decrease through the bronchial tree due to the general reduction of the flow velocity magnitude. The latter decreases with further generations due to the increase of global cross-sectional area. Remarkably, the secondary flows are weaker in the COPD subjects than in the normal subjects.

Figure 5.

Left: Secondary velocity vectors along cross-sections at generation G0 to G7, overlaid to contours of velocity magnitude. Vector indicating tracheal bulk velocity U0 shown for comparison. scale. Right: Secondary flow magnitude normalized by U0. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Discussion

Our results indicate that subjects with minimal or mild airflow obstruction exhibit measurable morphological differences in the conducting airways with respect to normal subjects, and in particular: smaller diameters, smaller child-to-parent diameter ratios, and larger length-to-diameter ratios. These differences are found analyzing the first seven generations of bronchial branching, as opposed to the “small airways” (less than 2 mm in internal diameter, i.e. the 4th to 14th bronchial generation) that are usually considered to be more directly affected by the development of COPD (Stewart & Criner 2013). A somewhat reduced diameter of the central airways is expected in subjects with mild airflow obstruction, as recently demonstrated by Washko et al. (2014) analyzing CT scans of a large cohort of our same subjects from COPDGene. Here we find that these morphological differences are more evident in subjects who later experience a severe decline in pulmonary function (for the same level of tobacco exposure). Besides the airway diameter, the fractal dimension of the reconstructed bronchial tree is also found to be smaller in subjects with airflow obstruction, and more so in those facing future decline in pulmonary function. Because the fractal dimension is a metric of tortuosity of biological trees (Nelson & Manchester 1988, Helmberger et al. 2014), this indicates that the airways of diseased subjects are less contorted and space-filling compared to normal subjects.

Several previous studies point to a relation between lung structural features and the onset/progression of COPD. An association has been demonstrated between low birth weight and death due to COPD (Barker et al. 1991). Women, who have smaller conducting airways than men even after correcting for height, appear to be more susceptible to smoke exposure (Sørheim et al. 2010). There is also compelling evidence that hereditary factors influence the development and severity of COPD (Lebowitz et al. 1984). However, most of the research aimed at identifying genetic factors has focused on genetic and molecular biomarkers (Cho et al. 2012). From the present study, it seems in fact plausible that the anatomic structure of the airways is a factor for the onset and development of COPD.

Concerning the mechanism relating airway morphology and disease progression, we find noteworthy that the child-to-parent branch diameter ratio h is consistently smaller in subjects with airflow limitation, and more so for those who will face further FEV1 decline. Mauroy et al. (2004) showed that the airflow resistance offered by a branching tree modeled on the human lung anatomy is extremely sensitive to the value of h: for ratios slightly smaller than the optimal value, the pressure drop across the tree diverges with the generation number, and the increased pressure can only be overcome by greater respiratory efforts. In this perspective, one can indeed expect that smaller h values correlate not only with present obstruction, but also with future decline of pulmonary function.

The effects of the morphological modifications (especially the airway lumen reduction) on the airflow patterns, and the consequent effects on the disease progression, are not trivial. As reviewed by Darquenne (2012), patients with obstructive lung disease usually experience increased bronchial aerosol deposition than healthy subjects (see e.g., Chung et al. 1988). In the conducting airways (where inertial impaction is the dominant deposition mechanism), this is likely due to the higher air velocity associated to the reduced airway diameter, which increases the likelihood that particles will deviate from the flow streamlines and deposit on the airway surface. Such a mechanism was demonstrated, e.g., by the detailed simulations of the particle-laden flow through the central airways of a cystic fibrosis pig model in Awadalla et al. (2014). Beyond the effect of increased streamwise (axial) velocity, the secondary (lateral) airflow velocities also play a major role in the transport and deposition of inhaled particles in the conducting airways (Fresconi & Prasad 2007, Bauer et al. 2012). In particular, these are expected to centrifuge inertial particles, enhancing deposition in the conducting airways (Zhang & Kleinstreuer 2002). We have recently shown that secondary velocities are significantly higher in realistic (e.g., CT-based) bronchial trees than in idealized (e.g., tubular and symmetric) airway models (Banko et al. 2015, Jalal et al. 2016). The present results indicate that secondary flows are smaller in the conducting airways of subjects with airflow obstruction. A possible reason is that the reduced airway diameter hinders the formation and development of the vortices in which these lateral motions are typically organized (Kleinstreuer & Zhang 2010). Moreover, the reduced tortuosity implied by the smaller fractal dimension, may imply weaker vortical motions since these are largely induced by the local branch curvature (Fresconi & Prasad 2007, Bauer et al. 2012). Regardless of the fluid dynamic cause, the consequences may be far-reaching: weaker lateral transport could reduce aerosol deposition, counteracting the effect of increased streamwise velocity due to lumen reduction. Lower deposition rates in the conducting tract could be unfavorable, allowing inhaled harmful particles to reach deeper generations. Further studies to investigate this possibility are warranted. In general, the changes in airflow features suggest that the morphological differences between COPD subjects and normal subjects should be interpreted within the framework of a structure-function relationship.

The present study has several limitations. The number of subjects on which the morphological analysis is carried out is limited, due to the lengthy nature of the segmentation process. Presently, automatic segmentation algorithms are not well established, but recent progresses may allow great speed up in the future (Reynisson et al. 2015, Nadeem et al. 2017), allowing efficient mining of the data from large clinical studies. The inspiratory flow study featured a rigid model. This is common in experimental (e.g., Grosse et al. 2007, Adler & Brucker 2007, de Rochefort et al. 2007, Soodt et al. 2012) and even in advanced numerical studies of respiratory flows in the central airways (Lambert et al. 2011, Feng & Kleinstreuer 2014). However, the effect of airway deformation may not be negligible, and requires solving the fluid-structure-interaction problem (Wall & Rabczuk 2008) and/or possessing time-resolved information on the airway motion and local ventilation (Yin et al. 2013). From the experimental standpoint, manufacturing a compliant model mimicking the behavior of the bronchial tree remains a challenge, although progresses are expected following the fast evolution of 3D printing methodologies. In our study the MRI-based flow measurements consisted of only one subject per group, which suggests caution in interpreting the results. For example, possible differences in secondary flow intensity between the stable COPD and the decliner COPD subjects might be hidden by the lack of statistical power. The MRI flow measurements provide great details on the full three-dimensional flow, but are involved and time-consuming. They provide, however, an excellent validation for numerical simulations which can be more efficient to extend the flow analysis to a larger number of subjects (e.g., Miyawaki et al. 2017). Finally, we have focused on morphology and airflow relative to the inspiratory phase, but it should be noted that the entire respiratory cycle is crucial for the transport processes, especially of aerosol particles (Oakes et al. 2016) and when the respiration frequency is elevated (Bauer & Brucker 2015).

In conclusion, the present analysis of CT-reconstructed bronchial trees indicates that smokers with even minimal/mild obstruction display morphological differences compared to smokers with normal lung function, and the difference is more evident for subjects that later experience a decline in pulmonary function. The secondary flows that characterize lateral dispersion along the airways are found to be less intense in the subjects with airflow obstruction, suggesting that particle transport and deposition processes might also differ. Overall these results confirm that structural and functional features of the bronchial tree are associated with the status and progression of the disease already at an early stage. This points towards the possibility of using novel imaging-based biomarkers to perform pre-symptomatic diagnosis, and to make more accurate predictions of the progression of obstructive lung diseases.

Highlights.

We investigate structure and function in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

We study airway morphology by segmenting and analyzing high-resolution CT scans.

We perform in vitro inhalation experiments in 3D printed models of subject airways.

We measure detailed inspiratory flow field by MRI velocimetry.

Airway morphology and inspiratory flow appear correlated with disease progression.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the access to the COPDGene database. We thank Sahar Jalal, Andras Nemes, and Omid Amili for help during the MRI measurements. Funding for this work was provided by the National Science Foundation (CBET-1453538), the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI-R21HL129906), and Boston Scientific Inc. COPDGene was supported by Award Number R01 HL089897 and Award Number R01 HL089856 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board comprised of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens and Sunovion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antonelli-Incalzi R, Imperiale C, Bellia V, et al. Do GOLD stages of COPD severity really correspond to differences in health status? Eur Respir J. 2003;22:444–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00101203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler K, Brücker C. Dynamic flow in a realistic model of the upper human lung airways. Experiments in Fluids. 2007;43(2):411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla M, Miyawaki S, Alaiwa MHA, Adam RJ, Bouzek DC, Michalski AS, … Stoltz DA. Early airway structural changes in cystic fibrosis pigs as a determinant of particle distribution and deposition. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2014;42(4):915. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Fall C, et al. Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ. 1991;303:671–675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6804.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer K, Rudert A, Brücker C. Three-Dimensional Flow Patterns in the Upper Human Airways. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2012;134(7):071006. doi: 10.1115/1.4006983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer K, Brücker C. The influence of airway tree geometry and ventilation frequency on airflow distribution. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2015;137(8):081001. doi: 10.1115/1.4030621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Castaldi PJ, Wan ES, Siedlinski M, Hersh CP, Demeo DL, … Silverman EK. A genome-wide association study of COPD identifies a susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q13. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21(4):947–957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KF, Jeyasingh K, Snashall PD. Influence of airway calibre on the intrapulmonary dose and distribution of inhaled aerosol in normal and asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 1988;1:890–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darquenne C. Aerosol deposition in health and disease. Journal of aerosol medicine and pulmonary drug delivery. 2012;25(3):140–147. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2011.0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darquenne C, van Ertbruggen C, Prisk GK. Convective flow dominates aerosol delivery to the lung segments. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011 Jul;111(1):48–54. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00796.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rochefort L, et al. In vitro validation of CFD simulation in human proximal airways reconstructed from medical images with hyperpolarized helium-3 MRI phase contrast velocimetry. J Appli Physiol. 2007;102(5):2012–2023. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01610.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins CJ, et al. Magnetic resonance velocimetry: applications of magnetic resonance imaging in the measurement of fluid motion. Experiments in Fluids. 2007;43(6):823–858. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Kleinstreuer C. Micron-particle transport, interactions and deposition in triple lung-airway bifurcations using a novel modeling approach. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2014;71:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. British medical journal. 1977;1(6077):1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresconi FE, Prasad AK. Secondary velocity fields in the conducting airways of the human lung. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2007;129(5):722–732. doi: 10.1115/1.2768374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenny RW, Robertson HT. Determinants of pulmonary blood flow distribution. Comprehensive physiology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cphy.c090002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotberg JB. Respiratory fluid mechanics and transport processes. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2001;3(1):421–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.3.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, et al. Time resolved analysis of steady and oscillating flow in the upper human airways. Experiments in fluids. 2007;42(6):955–970. [Google Scholar]

- Helmberger M, Pienn M, Urschler M, Kullnig P, Stollberger R, Kovacs G, … Bálint Z. Quantification of tortuosity and fractal dimension of the lung vessels in pulmonary hypertension patients. PloS one. 2014;9(1):e87515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EA, Simon BA, McLennan G. State of the Art. A structural and functional assessment of the lung via multidetector-row computed tomography: phenotyping chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2006;3(6):519–532. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-086MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lancet. 2004;364(9435):709–721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan DL, Shapiro AH, Kamm RD. Some features of oscillatory flow in a model bifurcation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1989;67(1):147–159. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstreuer C, Zhang Z. Airflow and particle transport in the human respiratory system. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 2010;42:301–334. [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz MD, Knudson RJ, Burrows B, Knudson RJ, Burrows B, et al. Family aggregation of pulmonary function measurements (1984) American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1984;129:8–11. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon FE, et al. Lung cancer - a fractal viewpoint. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2015;12(11):664–675. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markl M, et al. 4D flow MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2012;36(5):1015–1036. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minino AM, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: preliminary data for 2008. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2010;59(2):1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki S, Tawhai MH, Hoffman EA, Wenzel SE, Lin CL. Automatic construction of subject-specific human airway geometry including trifurcations based on a CT-segmented airway skeleton and surface. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology. 2017;16(2):583–596. doi: 10.1007/s10237-016-0838-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem SA, Jin D, Hoffman EA, Saha PK. Asian Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; Cham: 2016. Nov, A Novel Iterative Method for Airway Tree Segmentation from CT Imaging Using Multiscale Leakage Detection; pp. 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TR, Manchester DK. Modeling of lung morphogenesis using fractal geometries. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 1988;7(4):321–327. doi: 10.1109/42.14515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM, Shadden SC, Grandmont C, Vignon-Clementel IE. Aerosol Transport Throughout Inspiration and Expiration in the Pulmonary Airways. International journal for numerical methods in biomedical engineering. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cnm.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedley TJ. Pulmonary Fluid Dynamics. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1977;9(1):229–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pelc NJ, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance flow imaging. Magnetic resonance quarterly. 1994;10(3):125–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan EA, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2011;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynisson PJ, et al. Airway Segmentation and Centerline Extraction from Thoracic CT–Comparison of a New Method to State of the Art Commercialized Methods. PloS one. 2015;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SR, Kalhan R. Biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Translational research: the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2012;159(4):228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soodt T, Schröder F, Klaas M, van Overbrüggen T, Schröder W. Experimental investigation of the transitional bronchial velocity distribution using stereo scanning PIV. Experiments in fluids. 2012;52(3):709–718. [Google Scholar]

- Sørheim IC, Johannessen A, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS, Silverman EK, DeMeo DL. Gender differences in COPD: are women more susceptible to smoking effects than men? Thorax. 2010;65(6):480–485. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.122002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JI, Criner GJ. The small airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pathology and effects on disease progression and survival. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2013;19(2):109–115. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835ceefc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawhai MH, Lin CL. Airway gas flow. Comprehensive Physiology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Moortele T, Wendt C, Coletti F. Morphological and functional properties of the conducting airways in healthy subjects investigated by in vivo CT and in vitro MRI. J Appl Phys. 2017 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00490.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Durme YM, Verhamme KM, Aarnoudse AJ, et al. C-reactive protein levels, haplotypes, and the risk of incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;179(5):375–382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1540OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall WA, Rabczuk T. Fluid–structure interaction in lower airways of CT- based lung geometries. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids. 2008;57(5):653–675. [Google Scholar]

- Washko GR, et al. Computed tomographic measures of airway morphology in smokers and never-smoking normals. Journal of applied physiology. 2014 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00004.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Principles and methods for the morphometric study of the lung and other organs. Lab Investig J Tech Methods Pathol. 1963;12:131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West GB, et al. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science. 1997;276(5309):122–126. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West BJ, Bhargava V, Goldberger AL. Beyond the principle of similitude: renormalization in the bronchial tree. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1986;60(3):1089–1097. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.3.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TA. Design of the bronchial tree. Nature. 1969;18:668–669. doi: 10.1038/213668a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, et al. Simulation of pulmonary air flow with a subject-specific boundary condition. Journal of biomechanics. 2010;43(11):2159–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, et al. A multiscale MDCT image-based breathing lung model with time-varying regional ventilation. Journal of computational physics. 2013;244:168–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Kleinstreuer C. Transient airflow structures and particle transport in a sequentially branching lung airway model. Physics of Fluids. 2002;14(2):862–880. [Google Scholar]