Abstract

Aims

When patients with type 2 diabetes initiate insulin, metformin should be continued while continuation of other antihyperglycemics has unclear benefit. We aimed to identify practice patterns in antihyperglycemic therapy during the insulin transition, and determine factors associated with metformin continuation.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) trial which randomized overweight/obese adults under ambulatory care for type 2 diabetes to an intensive lifestyle intervention or diabetes support and education. Among the 931 participants who initiated insulin over ten years, we described longitudinal changes in antihyperglycemic medications during the insulin transition, and performed multivariable logistic regression to estimate the association between patient characteristics and metformin continuation.

Results

Before insulin initiation, 81.0% of patients used multiple antihyperglycemics, the most common being metformin, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones. After insulin initiation, metformin was continued in 80.3% of patients; other antihyperglycemics were continued less often, yet 58.0% of patients were treated with multiple non-insulin antihyperglycemics. Metformin continuation was inversely associated with age (fully adjusted (a) OR 0.60 per 10 years [0.42–0.86]), serum creatinine above safety thresholds (aOR 0.09 [0.02–0.36]), lower income (P=0.025 for trend), taking more medications (aOR 0.92 per medication [0.86–0.98]), and initiating rapid, short, or premixed insulin (aOR 0.59 [0.39–0.89]).

Conclusions

The vast majority of patients with type 2 diabetes continue metformin after insulin initiation, consistent with guidelines. Other antihyperglycemics are frequently continued along with insulin, and further research is needed to determine which, if any, patients may benefit from this.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2, Insulin / therapeutic use, Pharmacoepidemiology, Metformin / therapeutic use

1. Introduction

Due to the progressive nature of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, many patients will be treated with multiple glucose lowering drugs and eventually with insulin [1]. Insulin use was reported in over one fourth of ambulatory visits for type 2 diabetes in the U.S. in 2012 [2]. The American Diabetes Association and European Association for the Study of Diabetes have published guidelines for escalating antihyperglycemic therapy and initiating insulin [1, 3]. However, there is little guidance suggesting how a patient's non-insulin medications should be adjusted when insulin is started [1]. Therefore, determining how an antihyperglycemic regimen should be modified during the insulin transition can be a clinical challenge [4].

There is a consensus that metformin therapy should be continued after insulin initiation [1]. Evidence from clinical trials demonstrates that metformin in combination with insulin has beneficial effects on glycemic control, weight, cholesterol, and insulin dose compared to insulin monotherapy [5-9]. However, cross-sectional data suggest that insulin is more often used alone than in combination with metformin [2], and the reasons for this are not clear. The major contraindication to metformin is impaired renal function [10, 11], though other factors such as treatment complexity or side effects may be barriers to metformin use [11].

Regarding antihyperglycemics other than metformin, guidelines state that after insulin initiation these medications “may be discontinued on an individual basis” [1]. We identified no prior studies examining the continuation of non-insulin antihyperglycemics after insulin initiation, so the scope of this clinical challenge is not known.

Therefore, there is a need to determine how antihyperglycemic therapy is being modified with the transition to insulin therapy, and what factors may be driving those changes. In this study, we performed a retrospective analysis of longitudinal data from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) trial of patients with type 2 diabetes to describe changes in antihyperglycemic regimen during the transition to insulin therapy. In addition, we examined the patient factors associated with continuation of metformin after insulin is started, including sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, serum creatinine level, and medication burden.

2. Subjects, Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

The Look AHEAD trial enrolled 5,145 participants from 16 study centers throughout the U.S. between 2001 and 2004. Key eligibility criteria were self-reported type 2 diabetes confirmed by review of records, medications, or glycemic testing; aged 45 to 76 years; HbA1c <11% (97 mmol/mol); body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2 if not taking insulin; able to complete a maximal exercise test; and having a primary healthcare provider [12]. Key exclusion criteria were creatinine >1.5 mg/dL in men or >1.4 mg/dL in women; 4+ proteinuria; dialysis therapy; recent or exercise-limiting cardiovascular disease; cancer requiring treatment within the past five years; or chronic corticosteroid treatment [12]. Complete descriptions of the study design, eligibility, and recruitment have been published [12, 13] and are available online at https://www.niddkrepository.org/static/studies/look-ahead/Protocol.pdf.

This study is a retrospective analysis using the Look AHEAD distributed dataset which excludes participants from the Southwest Native American study sites due to consent limitations, resulting in a cohort of 4,901 participants. This study uses data from baseline through ten years of follow-up. Participants were included if they were not using insulin at either their screening or baseline visits, and initiated insulin during follow-up. Look AHEAD ascertained medication data by instructing participants to bring their home medications with them to yearly study visits. The names of prescription medications being used by participants at the time of the visit were recorded by trained staff. To ensure complete medications data for this study, we included only the participants who brought their home medications for review at the study visit at which the first use of insulin was recorded, and to the study visit one year prior to the first use of insulin. 71 of 1,002 eligible participants (7.1%) were excluded for not bringing home medications for review.

2.2 Look AHEAD interventions and outcomes

The Look AHEAD trial randomized participants 1:1 to an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) or Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) which is the control arm. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. Participants in the ILI arm received interventions aimed at achieving a goal weight loss of 7% of initial body weight, including a combination of behavioral, nutritional, and pharmacologic therapies [14]. Participants in the DSE arm received educational materials on diet and exercise and several group support sessions each year [15]. Participants in the ILI arm received some monitoring and adjustment of diabetes medications to prevent hypoglycemia according to a pre-specified protocol during the intervention period; otherwise participants received all medical care from their personal physicians without direction from Look AHEAD [12, 14].

The primary outcome of the Look AHEAD trial was the incidence of a composite cardiovascular endpoint including cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal stroke [12]; this was expanded to include hospitalization for angina after study year two [16]. In September 2012, the Look AHEAD intervention was stopped due to futility for the primary outcome after a median follow-up of 9.6 years [13]. Participants continue to be followed for study measures and outcomes.

2.3 Study Measures

The ascertainment of medications data is described in section 2.1. For this study, insulin initiation was defined as occurring between the study visit in which the first use of any insulin medication was recorded and the study visit one year prior. Therefore, the visit at which the first use of insulin was recorded was described as the visit after insulin initiation, and the visit one year prior was described as the visit before insulin initiation. The type of insulin initiated was used to create two groups representing different treatment strategies [1]: 1) long acting insulin alone, and 2) rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, with or without long acting insulin. Non-insulin antihyperglycemic medications were categorized by pharmacologic class; SGLT-2 inhibitors were not included as they were not in use during the study period. A medication class was considered to be continued after insulin initiation if it was being used both before and after insulin initiation; a medication class was considered to be initiated if it was not used before insulin initiation and was used after insulin initiation.

Sociodemographic data was self-reported. Family income, employment status, insurance status, and source of medical care were ascertained by questionnaire in the clinic setting yearly through study year four. Anthropometry was performed yearly by standardized protocols. Hypertension was defined as systolic/diastolic blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medication(s). Dyslipidemia was defined as LDL cholesterol >130 mg/dL or use of lipid lowering medication(s). Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was self-reported at baseline, though all participants had to pass a maximal exercise stress test for inclusion; during follow-up CVD was ascertained by self-report and confirmed with adjudication of medical records [13]. Laboratory measurements for serum creatinine and HbA1c were performed as single measurements at study visits yearly through study year four, and on alternating years thereafter. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the CKD-Epi equation [17]. For analysis of predictors of metformin continuation, serum creatinine was dichotomized according to the pre-2016 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling stating that metformin was contraindicated with creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL in men or ≥1.4 mg/dL in women [3]. The FDA threshold for serum creatinine, as opposed to other measures of renal function such as eGFR, was used in this analysis as these were the relevant clinical guidelines in the U.S. concurrent to the study period [3]. Study measures are reported at the visit after insulin initiation; for measures not ascertained at that visit, the most recent previously recorded value was used.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Participant characteristics and patterns of medication use are described by means and proportions. Among participants taking metformin before insulin initiation, we performed logistic regression for the outcome of continuing metformin after insulin initiation using two multivariable models. Model 1 is adjusted for study arm and the study year at which insulin initiation occurred as a nominal categorical variable to account for potential confounding by study design and temporal trends. Model 2 is additionally adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that were considered potentially relevant to metformin use (Table 4). For analysis of yearly family income, significance was determined by the global Wald test combining all income categories, and also by a test for linear trend across categories. Two-sided P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using STATA 14 software (StataCorp LP, College Station TX). These analyses were not conducted at the Look AHEAD Coordinating Center, and this is not the work of the Look AHEAD study group.

2.5 Sensitivity Analyses

To determine if inclusion of participants in the ILI study arm affected the proportion of participants continuing metformin or the result of logistic regression for predictors of metformin continuation, we performed these analyses restricted to participants in the DSE arm only and compared these results to those obtained in the primary analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics after insulin initiation of the 931 participants who met inclusion criteria. The mean age was 63.6 years, 57.6% were female, 72.7%, 11.3%, 11.7%, and 4.3% were white, black, Hispanic, and other races, respectively. The mean HbA1c was 7.9% (63 mmol/mol), and participants were using a mean of 2.9 antihyperglycemic drugs. Participants reported a wide distribution of yearly family income levels; 26.9% of participants were unemployed; 5.2% had no medical insurance. The analysis of predictors of metformin continuation was performed in the 747 participants who were using metformin prior to insulin initiation; the characteristics of these participants were similar to those of the full cohort except fewer had creatinine values above the pre-2016 FDA threshold for metformin use (Supplemental Table S1). Temporal trends in antihyperglycemic medication use among study participants can be found in Supplemental Table S2.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at the study visit after insulin initiation.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of participants, n | 931 |

| Age, years | 63.6 (6.9) |

| Female gender | 536 (57.6) |

| Race / ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 677 (72.7) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 105 (11.3) |

| Hispanic | 109 (11.7) |

| Other | 40 (4.3) |

| Income | |

| >$80,000 | 308 (34.1) |

| $60,000-$80,000 | 160 (17.7) |

| $40,000-$60,000 | 157 (17.4) |

| $20,000-$40,000 | 179 (19.8) |

| <$20,000 | 99 (11.0) |

| Unemployed | 250 (26.9) |

| No medical insurance | 48 (5.2) |

| Source of medical care | |

| Private office | 749 (80.5) |

| Hospital outpatient department | 114 (12.2) |

| Community health center | 28 (3.0) |

| Other or no usual care | 40 (4.3) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.88 (0.31) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 83.0 (19.2) |

| Serum creatinine above thresholda | 30 (3.2) |

| HbA1c, % | 7.9 (1.6) |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 63 (17) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35.6 (6.2) |

| Hypertension | 844 (90.7) |

| Dyslipidemia | 796 (85.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 175 (18.8) |

| Number of antihyperglyemic drugs | 2.7 (0.9) |

| Total number of drugs | 7.8 (3.1) |

| Type of insulin initiated | |

| Long acting only | 530 (56.9) |

| Other insulin typesb | 401 (43.1) |

| Randomized to ILI arm | 408 (43.8) |

| Study year of insulin initiation | 5.4 (2.6) |

Values are mean (SD) or frequency (% of column). eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL (men) or ≥1.4 mg/dL (women).

Includes participants using rapid acting (187 participants, 20.1%), short acting (207 participants, 22.2%), or premixed insulin (21 participants, 2.3%), with or without long acting insulin.

3.2 Antihyperglycemic regimens before and after insulin initiation

The non-insulin antihyperglycemic regimens used by participants before and after insulin initiation are shown in Table 2. Before insulin initiation, most participants (81.0%) were using regimens consisting of multiple antihyperglycemic compounds, with metformin-based combinations being the most common. Metformin, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones were the most common antihyperglycemic classes, and some combination of these comprised 72.2% of antihyperglycemic medications used. After insulin initiation, participants were more likely to be using no non-insulin antihyperglycemics (2.9% before vs. 12.4% after) or a single compound (16.1% before vs. 29.6% after). The use of metformin as the only non-insulin antihyperglycemic increased from 8.4% before to 17.1% after insulin initiation. However, multi-drug regimens continued to be common after insulin initiation, with 58.0% of participants using two or more antihyperglycemic compounds in conjunction with insulin.

Table 2.

Non-insulin antihyperglycemic medication profile before and after insulin initiation.

| Antihyperglycemic treatment | Treatment before initiating insulin (n=931) | Treatment after initiating any insulin (n=931) | Treatment after initiating long acting insulin only (n=530) | Treatment after initiating other insulin typesb (n=401) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No antihyperglycemicsa | 27 (2.9) | 115 (12.4) | 30 (5.7) | 85 (21.2) |

| Single compounda | 150 (16.1) | 276 (29.6) | 130 (24.5) | 146 (36.4) |

| Metformin | 78 (8.4) | 159 (17.1) | 62 (11.7) | 97 (24.2) |

| Sulfonylurea | 58 (6.2) | 82 (8.8) | 47 (8.9) | 35 (8.7) |

| Thiazolidinedione | 7 (0.8) | 18 (1.9) | 11 (2.1) | 7 (1.7) |

| Meglitinide | 3 (0.3) | 7 (0.8) | 6 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) |

| GLP-1 receptor agonist | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.7) |

| α-glucosidase inhibitor | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Two compoundsa | 433 (46.5) | 378 (40.6) | 251 (47.4) | 127 (31.7) |

| Metformin + Sulfonylurea | 284 (30.5) | 228 (24.5) | 145 (27.4) | 83 (20.7) |

| Metformin + TZD | 38 (4.1) | 45 (4.8) | 29 (5.5) | 16 (4.0) |

| Metformin + DPP-4 inhibitor | 16 (1.7) | 23 (2.5) | 15 (2.8) | 8 (2.0) |

| Metformin + GLP-1 receptor agonist | 14 (1.5) | 19 (2.0) | 14 (2.6) | 5 (1.2) |

| Sulfonylurea + TZD | 42 (4.5) | 22 (2.4) | 15 (2.8) | 7 (1.7) |

| Other two-compound combinations | 39 (4.2) | 41 (4.4) | 33 (6.2) | 8 (2.0) |

| Three or more compoundsa | 321 (34.5) | 162 (17.4) | 119 (22.5) | 43 (10.7) |

| Metformin + Sulfonylurea + TZD | 165 (17.7) | 74 (7.9) | 54 (10.2) | 20 (5.0) |

| Metformin + Sulfonylurea + DPP-4 inhibitor | 35 (3.8) | 24 (2.6) | 21 (4.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| Metformin + Sulfonylurea + GLP-1 receptor agonist | 37 (4.0) | 22 (2.4) | 14 (2.6) | 8 (2.0) |

| Other combinations | 84 (9.0) | 42 (4.5) | 30 (5.7) | 12 (3.0) |

Values are frequency (% of column). TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Rows indicating the number of antihyperglycemic compounds are mutually exclusive.

Includes participants using rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, with or without long acting insulin.

Changes in antihyperglycemic therapy during the insulin transition were most pronounced in participants who initiated rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, as compared to those who initiated long acting insulin alone (Table 2). After initiating rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, 21.2% of participants were using no non-insulin antihyperglycemics and 36.4% were using a single medication. Still, 42.4% of these participants were treated with two or more non-insulin antihyperglycemics.

3.3 Changes to antihyperglycemic therapy after insulin initiation

Metformin was continued after insulin initiation by 80.3% of participants who were previously taking metformin (Table 3). Antihyperglycemics in other classes were continued less often, ranging from 21.4% of participants continuing α-glucosidase inhibitors to 65.0% continuing sulfonylureas. All antihyperglycemics were less likely to be continued among participants who initiated rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, compared to those who initiated long acting insulin only (Table 3).

Table 3.

Proportion of participants continuing non-insulin antihyperglycemic therapy from before to after insulin initiation.

| Antihyperglycemic class | Continued after initiating any insulin | Continued after initiating long acting insulin only | Continued after initiating other insulin typesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin | 600/747 (80.3) | 360/426 (84.5) | 240/321 (74.8) |

| Sulfonylureas | 454/699 (65.0) | 299/401 (74.6) | 155/298 (52.0) |

| Thiazolidinediones | 161/322 (50.0) | 111/202 (55.0) | 50/120 (41.7) |

| Meglitinides | 22/45 (48.9) | 19/33 (57.6) | 3/12 (25.0) |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 52/100 (52.0) | 40/65 (61.5) | 12/35 (34.3) |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | 39/92 (42.4) | 28/55 (50.9) | 11/37 (29.7) |

| α-glucosidase inhibitors | 3/14 (21.4) | 2/8 (25.0) | 1/6 (16.7) |

Values are the proportion (percent) of participants using the medication after insulin initiation among those using the medication before insulin initiation.

Includes participants using rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, with or without long acting insulin.

Among the 184 participants not taking metformin before insulin initiation, 23.9% initiated metformin after insulin initiation. Other antihyperglycemics were initiated infrequently (Supplemental Table S3).

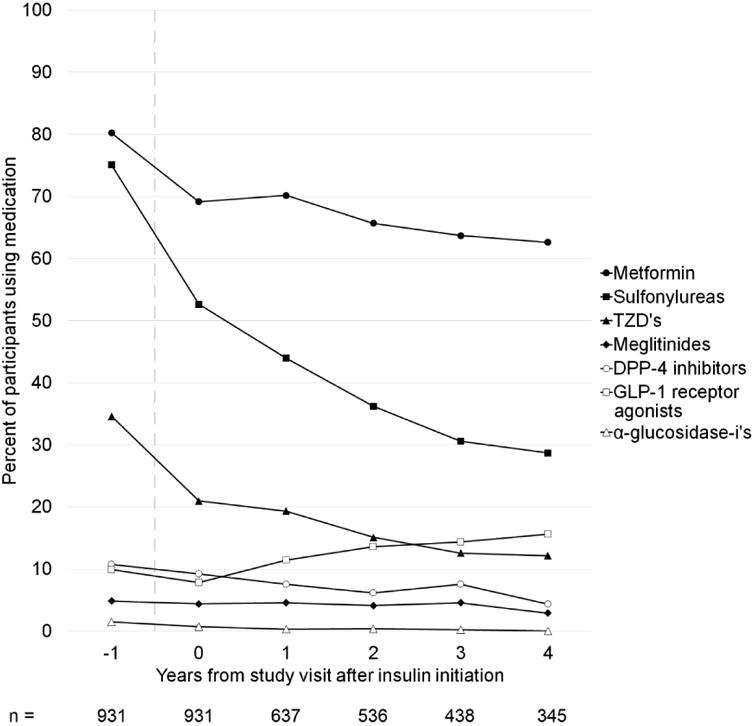

Among participants who continued to use insulin during the study period, the proportion taking metformin decreased with greater time from insulin initiation, falling from 69.2% of participants at the visit after insulin initiation to 62.6% of participants four years later (Figure 1). The proportion of participants using antihyperglycemics in other classes also decreased with time from insulin initiation, except for GLP-1 agonists which increased slightly.

Figure 1.

Use of non-insulin antihyperglycemics over time from insulin initiation.

Shown is the percent of participants using an antihyperglycemic drug in the designated class as a function of time from the study visit at which the first use of insulin is recorded (time = 0), truncated at 4 years after insulin initiation. The study visit before insulin initiation is shown (time = -1). The time period during which insulin is initiated is indicated by a vertical dashed line. Only participants who remained on insulin at the specified follow-up time are included. The number of participants included in the analysis at each time point is shown below the figure. TZD's, thiazolidinediones.

3.4 Predictors of metformin continuation

The results of logistic regression analysis for predictors of metformin continuation at the visit after insulin initiation are shown in Table 4. Both analytic models identified the same predictors of metformin continuation. Older age was inversely associated with metformin continuation with a fully adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.60 per 10 years (95% CI 0.42–0.86, P=0.006). Having a serum creatinine above the pre-2016 FDA threshold for metformin use (≥1.5 mg/dL in men or ≥1.4 mg/dL in women) was a strong negative predictor of metformin continuation (aOR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02–0.36, P=0.001). Also inversely associated with metformin continuation were having a lower family income (P=0.025 for trend), using a greater number of non-metformin medications (aOR 0.92 per additional medication, 95% CI 0.86–0.98, P=0.009), and initiating rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin (aOR 0.59, 95% CI 0.39–0.89, P=0.012). Neither Look AHEAD study arm nor study year at insulin initiation were associated with metformin continuation.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for continuation of metformin after insulin initiation.

| Characteristic | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.52 (0.39–0.70) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.42–0.86) | 0.006 |

| Female gender | 1.00 (0.61–1.29) | 0.990 | 1.04 (0.66–1.64) | 0.851 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.799 | 0.841 | ||

| White–non-Hispanic | reference | reference | ||

| Black–non-Hispanic | 0.80 (0.46–1.41) | 0.84 (0.44–1.60) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.93 (0.53–1.65) | 0.79 (0.41–1.51) | ||

| Other | 1.33 (0.50–3.57) | 1.18 (0.42–3.32) | ||

| Yearly family income | 0.001c | 0.042c | ||

| >$80,000 | reference | reference | ||

| $60,000-$80,000 | 0.87 (0.48–1.60) | 0.90 (0.47–1.71) | ||

| $40,000-$60,000 | 0.37 (0.21–0.63) | 0.41 (0.23–0.75) | ||

| $20,000-$40,000 | 0.49 (0.29–0.84) | 0.58 (0.32–1.08) | ||

| <$20,000 | 0.45 (0.24–0.86) | 0.52 (0.23–1.16) | ||

| Unemployed | 0.78 (0.52–1.16) | 0.223 | 0.93 (0.59–1.47) | 0.761 |

| No medical insurance | 1.04 (0.47–2.34) | 0.919 | 0.91 (0.37–2.27) | 0.840 |

| Source of medical care | 0.813 | 0.434 | ||

| Private office | reference | reference | ||

| Hospital OPD | 1.20 (0.67–2.16) | 1.69 (0.85–3.35) | ||

| Community health center | 0.78 (0.30–2.01) | 0.99 (0.33–2.96) | ||

| Other or no usual care | 0.82 (0.34–1.97) | 0.79 (0.31–2.06) | ||

| Serum creatinine above thresholdd | 0.08 (0.02–0.31) | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.02–0.36) | 0.001 |

| HbA1c (per 1%, 11 mmol/mol) | 1.05 (0.92–1.20) | 0.463 | 1.00 (0.87–1.16) | 0.947 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.960 | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) | 0.963 |

| Number of non-metformin drugs | 0.89 (0.84–0.94) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.009 |

| Using rapid, short, or premixed insuline | 0.56 (0.39–0.81) | 0.002 | 0.59 (0.39–0.89) | 0.012 |

Only the participants who were using metformin before insulin initiation are included in this analysis (n=747).

Model 1: Adjusted for treatment arm and study year (covariates not shown).

Model 2: Adjusted for all listed covariates, treatment arm and study year.

The displayed P-value is by the global Wald test including all income categories. The P-value for linear trend across income categories is <0.001 for Model 1 and 0.025 for Model 2.

Serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL (men) or ≥1.4 mg/dL (women).

Includes participants using rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin, with or without long acting insulin. The reference group is participants using long acting insulin only.

Among participants who continued metformin, the mean serum creatinine was 0.82 ± 0.20 mg/dL, the maximum was 1.62 mg/dL, and four participants (0.7%) had serum creatinine above the FDA threshold. Among those who discontinued metformin, the mean serum creatine was 0.97 ± 0.40 mg/dL, the maximum 4.0 mg/dL, and eight participants (5.5%) were above the FDA threshold. Box plots of serum creatinine values among participants who continued and discontinued metformin can be found in Supplemental Figure S1.

3.5 Sensitivity analyses for study arm

We performed sensitivity analyses to determine if the results of the analysis of metformin continuation were affected by inclusion of participants in the Look AHEAD intervention (ILI) arm. The proportion of participants continuing metformin after insulin initiation was similar in both study arms (81.1% in the DSE arm vs. 79.3% in the ILI arm, P=0.55). Restricting to participants in the DSE arm (n=428), logistic regression identified the same predictors of metformin continuation with the exception of age which had the same effect direction, but was no longer statistically significant (aOR 0.65 per 10 years, P=0.096).

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the changes in non-insulin antihyperglycemic therapy during the insulin transition, finding that metformin was continued in 80.3% of patients initiating insulin, while other antihyperglycemics were continued less frequently. Even so, over half of patients continued to use two or more non-insulin antihyperglycemics after initiating insulin. These data suggest that most providers deliver care consistent with guidelines to continue metformin after insulin initiation; the continuation of other antihyperglycemics is a common occurrence that requires further study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining longitudinal changes in antihyperglycemic therapy after insulin initiation. Previous cross-sectional studies have found that insulin is often used as monotherapy, and its use in combination with non-metformin antihyperglycemics is uncommon [2]. In this study of insulin initiators, the most frequently used antihyperglycemic medications were metformin, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones, and medications in these classes were continued in over half of participants after insulin initiation. However, among patients who continued taking insulin, the use of these antihyperglycemics decreased steadily over time. GLP-1 receptor agonists were the only antihyperglycemic class used more frequently with a longer duration of insulin therapy; this was likely due to temporal trends as medications in this class were introduced during the study period (Supplemental Table S2). These findings suggest that patients often continue non-insulin antihyperglycemics during the insulin transition, and then progress towards insulin monotherapy over time.

The results of this study highlight the need for more research examining the safety and efficacy of non-metformin antihyperglycemics after insulin initiation. Although there is a lack of consensus guidelines regarding the use of antihyperglycemics other than metformin in combination with insulin, important considerations have been identified. The continuation of insulin secretagogues has been associated with increased weight gain and hypoglycemia [4, 18], and for these reasons some authors recommend these medications be stopped after insulin initiation [19, 20]. Also, the use of non-metformin antihyperglycemics in combination with insulin may increase financial cost and treatment complexity unnecessarily, as there is a lack of evidence for benefit in this setting [18].

We explored whether changes in antihyperglycemic therapy during the insulin transition differed depending on the type of insulin initiated, as patients requiring only basal insulin may be managed differently from those requiring insulin administered in multiple daily doses [1]. We found that participants initiating long acting insulin alone were more likely to continue metformin and other antihyperglycemics after insulin initiation compared to those initiating rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin. However, the majority patients in the latter group continued metformin after insulin initiation, and a substantial minority (42.4%) were treated with multiple non-insulin antihyperglycemics after insulin initiation. Therefore, continuation of metformin and other antihyperglycemics was common regardless of the type of insulin initiated.

As metformin continuation has proven benefits after insulin initiation [5-9], we also explored the factors associated with metformin continuation. We found that high serum creatinine was inversely associated with metformin continuation, and very few patients continued metformin with creatinine above the threshold on pre-2016 FDA product labels. These findings suggest that renal safety is an important consideration for providers prescribing metformin during the insulin transition. In 2016, the FDA adopted less restrictive guidelines for metformin labeling based on eGFR [21] which were predicted to greatly expand the population who are metformin eligible [22]. This study suggests that interventions targeted at increasing the implementation of the new FDA guidelines may increase rates of metformin continuation after insulin initiation.

We also found that metformin continuation was inversely associated with older age, having a lower income, taking a greater number of medications, and using rapid acting, short acting, or premixed insulin. It is possible that providers are choosing to simplify antihyperglycemic regimens in patients who may be at a higher risk from polypharmacy [11]; further study is needed to explore this. Additionally, it is interesting that having a lower income is a negative predictor of metformin continuation in this largely medically insured population. It is possible that this finding reflects socioeconomic disparities in antihyperglycemic treatment, as prior studies have found that patients with lower income have less favorable glycemic control [23, 24]. The influence of socioeconomic factors on metformin use in patients initiating insulin requires further study.

The major strength of this study is that it uses rigorously collected longitudinal data of antihyperglycemic medications over a ten-year period. In addition, patients were closely followed in a clinical trial setting with standardized ascertainment of clinical and socioeconomic measures. This study also has several limitations. As data was collected at yearly study visits, medication changes at the exact time of insulin initiation are unknown and may be different than those observed in this study. Laboratory and socioeconomic measures were not ascertained at some visits during the study period, and measurements occurring further from the time of insulin initiation may less accurately reflect the patients' status or treatment at the time of insulin initiation. As this is a longitudinal study, there were temporal trends in antihyperglycemic medication options during the study period: notably DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists were introduced.

As the Look AHEAD trial enrolled patients from study centers throughout the U.S., this study represents a broad subset of ambulatory U.S. adults with type 2 diabetes. Only patients who were overweight or obese were enrolled, so the results of this study may not be representative of leaner patients. In addition, participants in this study were enrolled in a clinical trial, and may be different from the general population in adherence, access to medical care, and other characteristics. Nonetheless, in our sensitivity analyses examining only participants in the control arm of the study which was enhanced usual care, we found that the results were similar.

Overall, the continuation of metformin and other non-insulin antihyperglycemics is common after insulin initiation, and more work is needed to aid providers in making evidence-based treatment decisions during the insulin transition.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Metformin is continued in 80.3% of patients with type 2 diabetes initiating insulin.

Age, renal function, and other factors are associated with metformin continuation.

After insulin initiation, non-insulin antihyperglycemic use declines over time.

However, using multiple non-insulin antihyperglycemics with insulin remains common.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers 5T32HL007180-40, T32DK007751, and 2U01DK057149-17].

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Authors' contributions: S.J.P. and J.R.D. performed the analysis and prepared the manuscript. H.Y. and N.M.M. contributed to the study design and methods and reviewed/edited the manuscript. J.M.C. contributed to the study design, methods, and data collection, and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. 8. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:S64–S74. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner LW, Nartey D, Stafford RS, Singh S, Alexander GC. Ambulatory treatment of type 2 diabetes in the U.S., 1997-2012. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:985–92. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–9. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos RC, van Avendonk MJ, Jansen H, Goudswaard AN, van den Donk M, Gorter K, et al. Insulin monotherapy compared with the addition of oral glucose-lowering agents to insulin for people with type 2 diabetes already on insulin therapy and inadequate glycaemic control. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD006992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006992.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douek IF, Allen SE, Ewings P, Gale EA, Bingley PJ Metformin Trial Group. Continuing metformin when starting insulin in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2005;22:634–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aviles-Santa L, Sinding J, Raskin P. Effects of metformin in patients with poorly controlled, insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:182–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Relimpio F, Pumar A, Losada F, Mangas MA, Acosta D, Astorga R. Adding metformin versus insulin dose increase in insulin-treated but poorly controlled Type 2 diabetes mellitus: an open-label randomized trial. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 1998;15:997–1002. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(1998120)15:12<997::AID-DIA716>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz H, Gursoy A, Sahin M, Guvener Demirag N. Comparison of insulin monotherapy and combination therapy with insulin and metformin or insulin and rosiglitazone or insulin and acarbose in type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2007;44:187–92. doi: 10.1007/s00592-007-0004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemmingsen B, Christensen LL, Wetterslev J, Vaag A, Gluud C, Lund SS, et al. Comparison of metformin and insulin versus insulin alone for type 2 diabetes: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. BMJ. 2012;344:e1771. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasisht KP, Chen SC, Peng Y, Bakris GL. Limitations of metformin use in patients with kidney disease: are they warranted? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:1079–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross SA. Breaking down patient and physician barriers to optimize glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2013;126:S38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, Haffner SM, Hubbard VS, Johnson KC, et al. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled clinical trials. 2003;24:610–28. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, Jakicic J, Rejeski J, et al. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:737–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wesche-Thobaben JA. The development and description of the comparison group in the Look AHEAD trial. Clin Trials. 2011;8:320–9. doi: 10.1177/1740774511405858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brancati FL, Evans M, Furberg CD, Geller N, Haffner S, Kahn SE, et al. Midcourse correction to a clinical trial when the event rate is underestimated: the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Study. Clin Trials. 2012;9:113–24. doi: 10.1177/1740774511432726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarland MS, Knight TN, Brown A, Thomas J. The continuation of oral medications with the initiation of insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a review of the evidence. South Med J. 2010;103:58–65. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181c35776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raskin P. Why insulin sensitizers but not secretagogues should be retained when initiating insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24:3–13. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swinnen SG, Dain MP, Mauricio D, DeVries JH, Hoekstra JB, Holleman F. Continuation versus discontinuation of insulin secretagogues when initiating insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:923–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipska KJ, Flory JH, Hennessy S, Inzucchi SE. Citizen Petition to the US Food and Drug Administration to Change Prescribing Guidelines: The Metformin Experience. Circulation. 2016;134:1405–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuot DS, Lin F, Shlipak MG, Grubbs V, Hsu CY, Yee J, et al. Potential Impact of Prescribing Metformin According to eGFR Rather Than Serum Creatinine. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2059–67. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houle J, Lauzier-Jobin F, Beaulieu MD, Meunier S, Coulombe S, Cote J, et al. Socioeconomic status and glycemic control in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: a mediation analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4:e000184. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jotkowitz AB, Rabinowitz G, Raskin Segal A, Weitzman R, Epstein L, Porath A. Do patients with diabetes and low socioeconomic status receive less care and have worse outcomes? A national study. Am J Med. 2006;119:665–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.