Abstract

The molecular pathways driving mesenchymal glioblastoma (GBM) are still not well understood. We report here that truncated glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (tGLI1) is a tumor-specific transcription factor that facilitates GBM growth, is enriched in the mesenchymal subtype of GBM and glioma stem cells (GSC), and promotes mesenchymal GSC by upregulating transcription of CD44. In an orthotopic GBM xenograft mouse model, tGLI1-overexpressing tumors grew more aggressively with increased proliferation and angiogenesis compared to control and GLI1-overexpressing xenografts. tGLI1 was highly expressed in GBM clinical specimens but undetectable in normal brains, whereas GLI1 was expressed in both tissues. A tGLI1 activation signature (tGAS) correlated with glioma grade, tumor angiogenesis, and poor overall survival, and GBM with high tGAS were enriched with mesenchymal GBM/GSC gene signatures. Neurospheres contained increased levels of tGLI1, but not GLI1, compared to the monolayer culture; mesenchymal GSC expressed more tGLI1 than proneural GSC. Ectopic tGLI1 expression enhanced the ability of mesenchymal GSC to yield neurospheres in vitro and form tumors in mouse brains. Selective tGLI1 knockdown reduced neurosphere formation of GBM cells. tGLI1 bound to and transactivated the promoter of the CD44 gene, a marker and mediator for mesenchymal GSC, leading to its expression. Collectively, these findings advance our understanding of GBM biology by establishing tGLI1 as a novel transcriptional activator of CD44 and a novel mediator of mesenchymal GBM and GSC.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, Glioma Stem Cells, tGLI1, CD44, Mesenchymal

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and most lethal brain tumor in adults accounting for 15% of all brain tumors. GBM Prognosis remains poor, with a median survival of 14 months and less than 5% of patients surviving five years post diagnosis (1,2). Extensive genomic analyses have divided GBMs into 3–4 distinct subtypes with slight variations (3,4). The proneural and mesenchymal subtypes of GBM are commonly delineated across two classification systems. Mesenchymal GBMs tend to respond poorly to chemotherapy and radiation, associated with a worse prognosis (3–5).

Recent studies of GBM identified subpopulations of tumor cells exhibiting stem cell-like properties, including the ability to self-renew, persistently proliferate, and differentiate into multiple cell lineages (6). The subpopulation of stem-like cells, or glioma stem cells (GSCs), is a key driver of tumor initiation, recurrence, and chemoresistance (7). Recently, patient-derived GSCs were identified to contain two distinct and mutually exclusive subtypes termed proneural and mesenchymal (8,9). CD44 was identified as a key marker of mesenchymal GSCs (8). High CD44 expression in GBM is predictive of poorer overall survival and is associated with increased GBM invasion, proliferation, and chemoresistance (10). Mesenchymal GSCs were found to be more aggressive and radioresistant; therefore, understanding the signaling pathways controlling the mesenchymal GSC phenotype is the key to developing targeted treatments for mesenchymal GSCs in GBM.

Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway plays an essential role in GSC function (11). The glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (GLI1) family of zinc-finger transcription factors function as the terminal effectors of the SHH signaling pathway (12). Our laboratory discovered truncated GLI1 (tGLI1) as a novel alternatively spliced, gain-of-function variant of GLI1 with a 41 amino acid deletion spanning the entire exon 3 and part of exon 4, but retains all of the known functional domains of GLI1 (13). We reported that tGLI1 regulates known GLI1 target genes to a similar degree as wild-type GLI1 (13), but gained the ability to transcriptionally activate genes not regulated by GLI1, including CD24, HPA1, TEM7, VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and VEGFR2, thus promoting cancer cell growth, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis (13–17). We also showed that tGLI1 is detectable only in cell lines, patient-derived xenografts, and primary specimens of GBM, but is undetectable in normal brain tissue or other normal human tissues (18). The tumor-specific expression pattern of tGLI1 in invasive breast cancer was reported in our previous study (19). Other groups have confirmed our findings that tGLI1 is detectable in triple-negative breast cancer (20) and malignant gliomas (21). Metastatic hepatoma cells also express tGLI1 (22).

GLI1 has been shown to drive transcription of pluripotency markers in cancer stem cells; however, the role that gain-of-function tGLI1 plays in cancer stem cells function remains unknown (11,23). It is also unknown whether tGLI1 promotes GBM progression using orthotopic xenograft mouse models. To address these gaps of knowledge, we initiated the current study including two different animal models, and found that tGLI1 drives the formation of larger, more proliferative, and more highly vascularized tumors than GLI1 in orthotopic GBM and GSC xenograft mouse models. Mechanistic studies provided evidence linking tGLI1 to mesenchymal GBM and GSCs. Our results also established tGLI1 as a novel transcriptional activator of the CD44 gene, a known marker and regulator of mesenchymal GSCs and also other cancer types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and patient specimens

U373MG cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured according to their recommendations. Luciferase-expressing G48LL2 cells were developed by Dr. Waldemar Debinski (24). BTCOE 4810/4795 cell lines were developed and validated from patient tumors at Brain Tumor Center of Excellence (25). Patient-derived Glioma Stem Cells (proneural GSC-11 and GSC-23; mesenchymal GSC-20 and GSC-28) were kind gifts from Drs. Erik Sulman and Krishna Bhat at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (8). GSCs were passaged under neurosphere-forming conditions in serum-free DMEM/F12 growth medium supplemented with B27, FGF, and EGF, in order to preserve stem-like properties. All cells used were tested every six months for mycoplasma; only cells free of mycoplasma were used in the studies. Normal brain tissue microarray (BNC17011) and glioma tissue microarray (GL2083) were purchased from US Biomax. Additional GBM samples were from Wake Forest Brain Tumor Center of Excellence (25). We have obtained written informed consent from the patients; the studies were approved by Wake Forest institutional review board and were conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines.

Generation of lentiviral GLI1- and tGLI1-expressing vectors and isogenic stable cell lines

The open reading frame for tGLI1 and GLI1 were cloned into the lentiviral expressing vector pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-RFP-Puro (CD516B-2) by System Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA). Plasmids were sequenced to confirm insertion of tGLI1 and GLI1 open reading frames. Lentiviral packaging was performed using a 3rd generation lentiviral pPACK packaging system from System Biosciences. The pPACK packaging plasmids along with the tGLI1 or GLI1 lentiviral expressing plasmid were co-transfected into 293TN cells for 48–96 hrs and the cell culture medium was subsequently collected. Viral particles were concentrated, titers measured, and used to infect G48LL2 and GSC-28 cells. Infected cells were treated with puromycin and FACS sorted for RFP-positive cells.

Animal studies

Female nude mice 6–8 weeks of age were used. Actively growing G48LL2 or GSC-28 cells were injected at a concentration of 1–5 × 105 cells in 5 μL PBS into the right frontal lobe. For the GSC-28 in vivo study, immediately prior to inoculation into mouse brain, GSC-28 neurospheres were harvested and disassociated to single cell suspension. Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine mixture to the coronal suture through a scalp incision according to an approved IACUC protocol. For bioluminescent imaging, xenograft-bearing mice were injected with d-luciferin intraperitoneally at 100 mg/kg body weight and then imaged weekly using PerkinElmer IVIS100 imager.

tGLI1 activated signature (tGAS) and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

tGAS was generate by averaging the median-centered expression of the six tGLI1 target genes (CD24, VEGFA, VEGFC, HPA1, TEM7, VEGFR2) (13–17). GSEA was performed by generating the Gene MatriX file (.gmx) by using published signatures for Angiogmatrix (26), the TCGA GBM subtypes (4), the Phillips GBM subtypes (3), and the GSC subtypes (8). The Gene Cluster Text file (.gct) was generated from the TCGA GBM dataset. The Categorical Class file (.cls) was generated based on the tGAS score or the GLI1 expression of patients in the TCGA GBM dataset. The number of permutations for GSEA was set to 1,000 and we used the TCGA gene list as the chip platform. For generation of heat maps, patients were divided into high or low tGAS score and the genes included in the map were genes within the published signatures for the indicated GBM subtypes (3,4). Heat maps were generated using Morpheus software developed by the Broad Institute.

tGLI1 knockdown using a tGLI1-targeting Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Oligonucleotide

A tGLI1-targeting Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) oligonucleotide and a non-targeting control oligonucleotide were custom made by Exiqon. Sequence for the control LNA oligonucleotide is C+T+G+T+C*T*T*C*A*G*T*T*C+A+A+C. BLAST analysis did not reveal binding of the control oligonucleotide to any genes. Sequence for the tGLI1-targeting LNA oligonucleotide is C+A+A+C+T*T*G*A*C*T*T*C*T+G+T+C. Phosphorothioated basea are indicated by * while LNA bases are labelled by +. Both modifications make the oligonucleotides resistant to nuclease-mediated degradation. U373MG GBM cells with high endogenous tGLI1 expression were transfected for 48 hours using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and then seeded for the neurosphere formation assay. tGLI1 and GLI1 mRNA expression was determined by RT-qPCR.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean±SE. The student’s t-test, Pearson Correlation, univariate/multivariate COX proportional hazards tests, and One-way ANOVA were performed using Sigma Plot version 11.0.

RESULTS

tGLI1 promotes growth of GBM in an orthotopic mouse model

Whether tGLI1 plays a role in promoting GBM intracranial growth has not been investigated. Herein, we generated isogenic cell lines from a low-passage G48LL2 human GBM cell line stably expressing empty vector, GLI1, or tGLI1 (Fig. 1A). Expression levels for GLI1 and tGLI1 in these cell lines are similar to those found in GBM specimens (Fig. 1A-bottom). The isogenic lines were implanted intracranially into female nude mice and tumor growth was tracked by weekly bioluminescence imaging. Results showed that GBM cells expression tGLI1 formed larger tumors (Fig. 1B). Representative images are shown in Figs. 1C–D. Analysis of brain sections using IHC indicated increased proliferation index (Ki-67 IHC) and increased microvessel density (CD31 IHC) in tGLI1-expressing tumors (Figs. 1E–H). Representative IHC images are shown in Fig. 1I. Using custom GLI1- and tGLI1-specific antibodies that we developed and validated (17), we further examined GBM specimens and normal brain tissues for GLI1 and tGLI1 expression, and found tGLI1 to be highly expressed in GBM samples, but undetectable in normal brain whereas GLI1 is expressed in both samples (Figs. 1J–K). Results in Figure 1 demonstrate that tGLI1 promotes GBM tumor growth in the brain microenvironment and that tGLI1 is expressed in GBM but not in normal brain.

Figure 1. tGLI1 is expressed in a tumor-specific fashion and promotes intracranial GBM growth.

A) Isogenic G48LL2 GBM cell lines carrying lentiviral mock, GLI1, or tGLI1 vector were subjected to immunoblotting for GLI1 and tGLI1 expression (top panel). Expression levels for GLI1 and tGLI1 in these cell lines are similar to those found in GBM specimens as shown by IHC (bottom panel). B) tGLI1 rendered GBM more aggressive in growth. Isogenic luciferase-expressing G48LL2 cell lines were injected into the right frontal lobe of female nude mice (N=5 per group) and tumor growth was assessed weekly via bioluminescent imaging. C) Representative bioluminescent images of actively growing tumors at Day 56. D) Representative bioluminescent images of ex vivo mouse brains. E–I) tGLI1-overexpressing GBM xenografts were more proliferative and more vascularized Mouse brains were subjected to H&E staining and IHC with indicated antibodies. Immunostained sections were scored by a pathologist and H-scores were calculated. Panel I shows representative IHC images. J–K) tGLI1 is highly expressed in GBM specimens but not in normal brain tissues. A cohort of normal healthy brain tissues (N=80) and GBM patient samples (N=63) were subjected to IHC using GLI1- and tGLI1-specific antibodies. Immunostained sections were scored by a pathologist to derive H-scores. Panel K shows representative IHC images. Student’s t-test was used to compute p-values.

High tGLI1 activity is associated with poor overall survival of GBM patients and increased angiogenesis of GBM

We asked whether tGLI1 activity can be used as a prognostic indicator for GBM. To indicate tGLI1 activation status, we created a tGLI1 activation signature (tGAS) using expression levels of its six target genes (13–17). We then analyzed a GEO dataset (GSE4290) consisting of mRNA expression profiles of 23 normal brains, 45 grade II gliomas, 31 grade III gliomas, and 81 grade IV gliomas (GBMs) for tGAS, and found GBMs to have the highest tGAS scores (Fig. 2A). In contrast, GLI1 levels were not significantly different among 4 groups (Fig. 2B). Next, we examined whether tGAS was associated with clinical outcome for GBM patients using a TCGA GBM database and univariate/multivariate analyses, and observed that high tGAS resulted in high Hazard Ratios (HRs) (Fig. 2C), suggesting that tGLI1 activation is independently associated with poor overall survival of GBM patients. Kaplan-Meier analysis further showed that GBM patients with high tGAS were associated with worse overall survival compared to patients with low tGAS (Fig. 2D). In contrast, GLI1 mRNA was not associated with overall survival (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. High tGAS is associated with poor overall survival of GBM patients and increased angiogenesis of GBM samples.

A–B) tGLI1 is most activated in GBM across four grades of gliomas. tGAS scores (A) and GLI1 mRNA expression (B) were determined for patient tumors in GSE4290 dataset across normal healthy brain and glioma samples. Student’s t-test was used to compute p-values. NS, non-significant. C) Increased tGLI1 activity is independently associated with poor overall survival of GBM patients. Univariate and multivariate COX proportional hazards were calculated using tGAS score, GLI1 expression, patient age, patient sex, Karnofsky Performance Score (KPS), and tumor size as variables. HR, hazard ratio. The TCGA GBM dataset was used with the outcome variable being overall survival. D–E) Patients with high tGAS in their GBMs had worse overall survival compared to those to low tGAS. Kaplan-Meier survival graphs were drawn using high or low tGAS score (D) or GLI1 expression (E) and data from the TCGA GBM dataset. Log-rank method was used to compute p-values. F–I) tGAS positively correlated with GBM angiogenesis. tGAS score (F–G) or GLI1 expression (H–I) was correlated with markers of tumor vascularity using CD31 (F,H) and VE-cadherin (G,I) using regression analysis. J–K) GBMs with high tGAS were enriched with angiogenesis gene signature. GSEA was performed using the AngioMatrix signature that is representative of GBM angiogenesis. Patients were separated by high or low tGAS score (J) or GLI1 expression (K) using the TCGA GBM dataset. L–M) A positive correlation between tGAS and angiogenesis in GBM specimens. AngioMatrix signature score was correlated with tGAS score (L) or GLI1 expression (M) using the TCGA GBM dataset.

Results in Fig. 1H indicated that tGLI1 promoted GBM vascularity. To confirm this observation, we correlated tGAS with vascularity markers, and found tGAS but not GLI1 to significantly associate with CD31 and VE-Cadherin (Figs. 2F–I). GSEA with the AngioMatrix signature that has been shown to be associated with tumor vascularity in GBM (26) further indicated that GBMs with high tGAS, but not high GLI1, had significant enrichment with the AngioMatrix signature (Figs. 2J–M). Results in Figure 2 demonstrate that tGLI1, but not GLI1, is associated with poor overall survival and enhanced tumor angiogenesis in GBM patients.

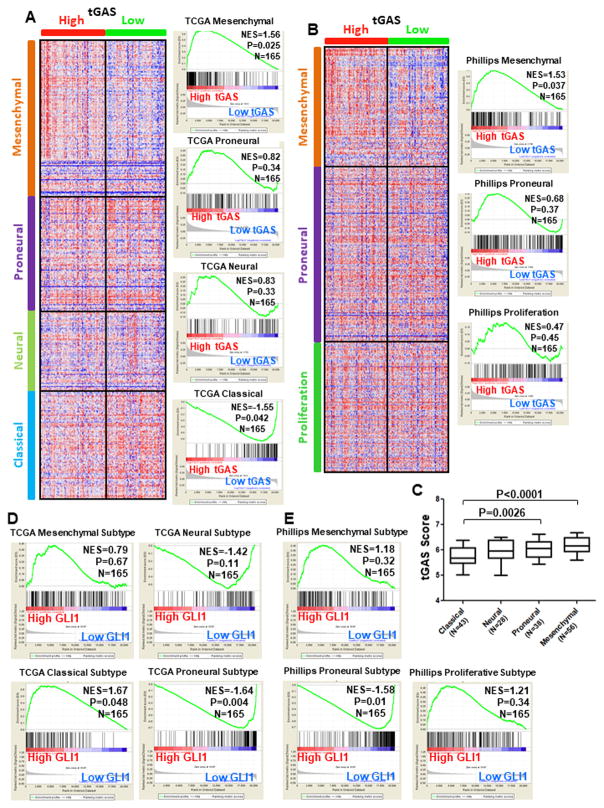

tGLI1 activation is enriched in the mesenchymal subtype of GBM

We examined whether the extent of tGLI1 activation differs among GBM subtypes. First, we divided the GBM cohort (TCGA) into two groups with high tGAS or low tGAS. We then used GSEA to determine the degrees of enrichment with established gene signatures for the four TCGA GBM subtypes, namely, mesenchymal, proneural, neural, and classical subtypes (4). As shown in Fig. 3A, GBM tumors with high tGAS were enriched for the TCGA mesenchymal gene signature, but not for the signatures for the other three subtypes. Interestingly, GBM tumors with low tGAS were significantly enriched for the TCGA classical signature, which is less aggressive than the mesenchymal subtype. Furthermore, we analyzed the same GBM cohort for the enrichment for another set of GBM subtype-specific gene signatures, namely, Phillips mesenchymal, proneural, and proliferation signatures (3). Consistent with the results of Fig. 3A, GBMs with high tGAS were enriched for the Phillips mesenchymal gene signature, but not the Phillips proneural or proliferation signatures (Fig. 3B). Mesenchymal GBMs had the highest tGAS scores among the four TCGA subtypes (Fig. 3C). In contrast, high GLI1 expression was not associated with either TCGA or Phillips mesenchymal subtype, but associated with the TCGA classical subtype (Fig. 3D). GBMs with low GLI1 were enriched with both TCGA proneural and Philiips proneural gene signatures (Fig. 3E). These findings indicate that tGLI1 activation is a hallmark of the mesenchymal GBM.

Figure 3. GBMs with high tGAS are enriched with the mesenchymal GBM gene signatures.

The TCGA dataset with the gene expression profile of 165 GBMs was used. A–B) GBM tumors with high tGAS were enriched for the TCGA and Phillips mesenchymal gene signatures, but not for those for the other subtypes. Heat maps were drawn using Morpheus software with patients separated by high or low tGAS score using genes in the signatures for each of the four TCGA GBM subtypes (A) or the three Phillips GBM subtypes (B). Right: GSEA. C) The mesenchymal subtype of GBMs had the highest tGAS scores among the four TCGA subtypes. tGAS score was determined for the four TCGA GBM subtypes. D–E) High GLI1 mRNA expression was not associated with either the TCGA or the Phillips mesenchymal subtype, but associated with the TCGA classical subtype. GSEA was performed using the signatures for the TCGA GBM subtypes (D) or the Phillips GBM subtypes and patients were separated by high or low GLI1 mRNA expression.

tGLI1 promotes neurosphere formation and transcriptionally activates CD44 expression

Mesenchymal GBM is associated with poor patient survival and multi-drug resistance, key clinical aspects of GBM thought to be driven by the cancer stem cell subpopulation (3,5,27). The role of GLI1 in GSC function has been studied; however, the role that tGLI1 plays in GSCs is unknown. We first compare monolayer culture with GSC-containing neurospheres for tGLI1 and GLI1 expression, and found tGLI1 but not GLI1 to be enriched in neurospheres (Fig. 4A). We further found that tGLI1-overexpressing cells formed significantly more neurospheres (Figs. 4B–C). Furthermore, we specifically knocked down tGLI1 expression in U373MG GBM cells with high endogenous tGLI1 expression to further determine the importance of tGLI1 in GBM. As shown in Fig. 4D, we designed and used a tGLI1-targeting Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) phosphorothioated oligonucleotide (oligo) that has been chemically modified to resist nuclease-mediated degradation. As shown in Fig. 4D-left, the tGLI1-targeting LNA oligo specifically knocked down tGLI1 expression but had no effect on GLI1. Importantly, GBM cells with tGLI1 knockdown showed a reduced ability to form neurospheres compared to cells with the non-targeting control LNA oligo (Fig. 4D-right). Blast analysis did not reveal binding of the control oligonucleotides to any genes. These results further support our conclusion that endogenous tGLI1 is essential for the neurosphere-forming ability of GBM cells.

Figure 4. tGLI1 promotes neurosphere formation and transcriptionally activates CD44 expression.

A) tGLI1 was significantly enriched in the neurospheres compared to the monolayer GBM cells. G48LL2 and BTCOE 4810 cell lines were collected under monolayer and neurosphere-forming conditions. Total RNA from cells were subjected to qPCR for tGLI1 and GLI1 levels. B–C) tGLI1-overexpressing cells formed significantly more neurospheres, suggesting an increase in the stem-like cell population. G48LL2 (B) and U373MG (C) cells with stable expression of vector, GLI1, or tGLI1 were subjected to the neurosphere assay. D) tGLI1 knockdown significantly inhibited neurosphere formation. U373MG cells transfected with the tGLI1-targeting or non-targeting control LNA oligos were subjected to the neurosphere assay. E) tGLI1 enhanced CD44 expression. Total RNA from G48a cells with stable expression of either vector or tGLI1 were subjected to qPCR for the indicated genes. F) tGLI1-expressing GBM cells had increased CD44(+) cells. Isogenic G48LL2 cell lines with stable expression of control or tGLI1 vector were subjected to flow cytometry with CD44 or CD133 antibodies. G) Preferential binding of tGLI1, but not GLI1, to the CD44 promoter. U373MG cells with transient expression of control vector or tGLI1 were subjected to the ChIP assay followed by PCR using primers for three regions of the CD44 gene promoter. H) tGLI1 transactivated the CD44 promoter in two GBM cell lines and HEK293 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with control or tGLI1 vector along with the CD44 promoter luciferase reporter, stimulated with SHH (100ng/mL) for 4 hrs, and subjected to the luciferase assay. I) SHH stimulation enhanced tGLI1-mediated activation of the CD44 gene promoter. BTCOE 4795 and U373MG cell lines were transiently transfected with control or tGLI1 vector together with the CD44 promoter luciferase reporter. Cells were then treated with or without SHH (100 ng/mL) for 4 hrs, harvested, and subjected to the luciferase assay. Student’s t-test was performed to calculate p-values. NS, not significant. All experiments were done at least three times to derive means and standard deviations.

To identify the mechanism by which tGLI1 promotes a GBM stem-cell phenotype, we determined the effects of tGLI1 on known stem cell-related genes and found that tGLI1-overexpressing GBM cells showed increased expression of CD44, along with a decrease in Sox2, Nanog, OCT4, and CD133 expression (Fig. 4E; Supplemental Table I). Flow cytometry confirmed increased CD44(+) cells in tGLI1-expressing GBM cells but no significant change in the CD133(+) population (Fig. 4F). CD44 is regarded as the marker for the mesenchymal GSCs while CD133 is the marker for the proneural GSCs (8). Using the ChIP assay, we detected preferential binding of tGLI1, but not GLI1, to three regions of the CD44 gene promoter (Fig. 4G; Supplemental Fig. 1), which show no homology to consensus GLI1-binding sequences. Using the luciferase assay, we showed that tGLI1 transactivated the CD44 promoter in two SHH-stimulated GBM cell lines and HEK293 cells (Fig. 4H) and that SHH enhanced tGLI1-mediated activation of the CD44 gene promoter (Fig. 4I; Supplemental Table II). Results in Figure 4 indicate a novel important role that tGLI1 plays in GBM stem-like cells and in the transcriptional activation of CD44.

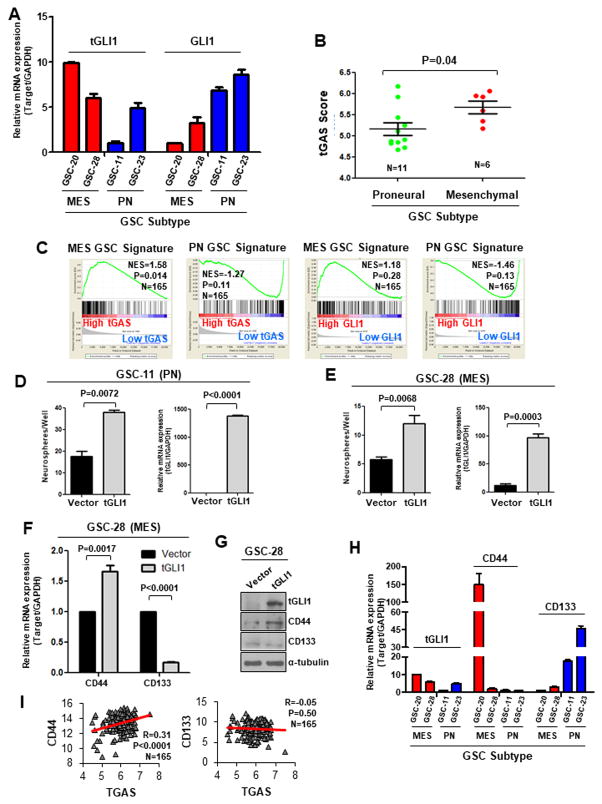

tGLI1 is preferentially expressed and activated in the mesenchymal subtype of GSC

Recent studies classified GSCs isolated from GBM specimens into the proneural (PN) or mesenchymal (MES) subtypes based on gene expression profiles (8,9). CD44 was defined as the marker for the MES GSCs whereas CD133 was for the PN GSCs. Since tGLI1 binds to and transactivates the CD44 promoter and tGLI1 is preferentially activated in MES GBM, we determined whether tGLI1 expression is associated with the MES subtype of GSC. Here, we examined patient-derived GSCs, two MES and two PN GSC neurospheres, and found the MES GSC neurospheres to express higher levels of tGLI1 and lower levels of GLI1 compared to PN GSC neurospheres (Fig. 5A). We also observed that MES GSC neurospheres had higher tGAS than the PN GSC neurospheres (Fig. 5B). We further analyzed a TCGA GBM dataset for the relationship between tGAS and GSC signatures, and observed that GBMs with high tGAS are enriched for the MES GSC signature, but not the PN GSC signature (Fig. 5C-left). In contrast, GLI1 was not enriched for either GSC signature (Fig. 5C-right).

Figure 5. tGLI1 is preferentially expressed and activated in the mesenchymal subtype of GSCs.

A) MES GSC neurospheres expressed higher levels of tGLI1 and lower levels of GLI1 compared to PN GSC neurospheres. Four different GSCs previously characterized as MES or PN subtype were subjected to total RNA extraction followed by RT-qPCR for tGLI1 and GLI1 expression levels. B) tGAS was significantly higher in MES GSC neurospheres (GSC-20 and GSC-28) compared to the PN GSC neurospheres (GSC-11 and GSC-23). tGAS scores were calculated for PN GSC (N=11) and MES GSC (N=6) lines that were isolated and profiled for expression by Bhat et al. (8). C) GBMs with high tGAS are enriched for the MES GSC signature, but not the PN GSC signature. The TCGA GBM dataset was analyzed by GSEA for the extent of enrichment with the MES and PN GSC signatures (8). Patients were divided into two groups according to tGAS (left) or GLI1 expression (right). D–E) tGLI1 overexpression increased neurosphere-forming capability of both PN (D) and MES (E) GSCs. GSC-11 (PN) and GSC-28 (MES) neurospheres transiently transfected with control vector or tGLI1 vector were subjected to the neurosphere assay (left) and RT-qPCR for tGLI1 expression levels (right). F–G) tGLI1 increased CD44 and decreased CD133 expression at the mRNA (F) and protein levels (G). H) High tGLI1-expressing MES GSC neurospheres expressed higher levels of CD44 and lower levels of CD133, compared to low tGLI1-expressing PN GSC neurospheres. Extracted total RNA was subjected to RT-qPCR for expression of tGLI1, CD44, and CD133. I) A positive correlation between tGAS and CD44, but not CD133 in GBM cohort (N=165). tGAS score was correlated with expression levels of CD44 or CD133 in the TCGA GBM dataset using Pearson correlation. Student’s t-test was used to calculate p-values.

We found that tGLI1 ectopic expression enhanced the neurosphere-forming capability of both PN and MES GSCs (Figs. 5D–E), and led to an increase in CD44 expression and a decrease in CD133 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figs. 5F–G). Further analysis of the four different GSCs indicated a pattern where high tGLI1-expressing MES GSC neurospheres expressed higher levels of CD44 and lower levels of CD133, compared to low tGLI1-expressing PN GSC neurospheres (Fig. 5H). Consistent with these observations, analysis of the TCGA GBM dataset revealed a positive correlation between tGAS and CD44, but not tGAS and CD133 (Fig. 5I). Collectively, results in Figure 5 demonstrate that tGLI1 is preferentially expressed and activated in the MES GSC neurospheres over PN GSC neurospheres, enhances expression of CD44, a MES GSC marker, and positively correlates with CD44 expression in a GBM cohort.

Increased tGLI1 expression enhanced the propensity of MES GSC to form xenografts

We have shown that tGLI1 ectopic expression promoted GBM growth in an orthotopic mouse model and that tGLI1 made GSCs formed greater numbers of neurospheres. In light of these observations, we aimed to validate our GSC findings in vivo. We first generated three isogenic MES GSC-28 isogenic lines with stable expression of control, GLI1 or tGLI1 lentiviral vectors (Fig. 6A). Of note, GSC-28 neurospheres express high endogenous tGLI1 (see Fig. 5A). Expression levels for GLI1 and tGLI1 in these stable GSC lines are similar to those found in GBM specimens as shown by IHC (Fig. 6A-bottom). GSC neurospheres were harvested and disassociated into single cell suspension, and were then implanted into the mouse brains; mice were imaged weekly. As shown in the growth curves and representative tumor images in Figs. 6B–D, increased tGLI1 expression rendered GSC-28 cells more aggressive in growths. Mice bearing tGLI1-expressing GSC-28 xenografts had a shortened survival time (Fig. 6E). IHC analyses further demonstrated that tGLI1-expressing GSC-28 tumors had the highest proliferative index (Ki-67 IHC) and microvessel density (CD31 IHC) (Figs. 6F–J). In summary, these results indicate that tGLI1 renders GSCs more aggressive in growth and angiogenesis in the brain microenvironment.

Figure 6. Increased tGLI1 expression enhanced the propensity of GSC to form xenografts.

A) Generation of isogenic GSC-28 cells with stable expression of control, GLI1, or tGLI1 vector. GSC neurospheres were analyzed by immunoblotting for GLI1 and tGLI1 levels (top panel). Expression levels for GLI1 and tGLI1 in these GSC lines are similar to those found in GBM specimens as shown by IHC (bottom panel). All GSC lines were maintained as neurospheres. B) GSC-28 cells expressing tGLI1 formed larger tumors compared to GLI1- or vector-expressing cells. Isogenic lines were implanted into the right frontal lobe of nude mice (N=6 per group) and tumor growth was assessed weekly via bioluminescent imaging. C) Representative images of actively growing tumors from animals. D) Representative images of ex vivo mouse brains. E) Mice bearing ectopic tGLI1-expressing GSC-28 xenografts had a shortened survival time. Kaplan-Meier survival graph is shown. Log rank test was used to determine p-values. F) Mouse brains were subjected to H&E staining and IHC with indicated antibodies. Representative images are shown. G–J) tGLI1-expressing GSC-28 tumors had the highest proliferative index and microvessel density. Immunostained mouse brains were scored to determine H-scores. Student’s t-test was used to compute p-values.

DISCUSSION

We made the following important novel observations in this study: a) tGLI1 promotes neurosphere-forming ability of GBM and GSCs in vitro, and their intracranial growth and angiogenesis in vivo; b) tGLI1 is highly expressed in GBM but undetectable in normal brain whereas GLI1 is equally expressed in both tissues ; c) tGLI1 is predominantly activated in the mesenchymal subtype of GBM and GSCs that are more aggressive among different subtypes (4).; d) GBM patients with high tGLI1 activity in their tumors had shortened overall survival of GBM patients and increased tumor angiogenesis, compared to those with low tGLI1 activity; and e) tGLI1 functions as a transcriptional activator of CD44. By reporting these findings, our study advances the biological understanding of GBM and GSCs and transcriptional regulation of an important stem cell marker/mediator CD44.

Our bioinformatics analyses revealed tGLI1 activation as a hallmark of the mesenchymal GBM and GSCs, which is an important finding. We used two independent mesenchymal gene signatures and found both signatures to be highly enriched in GBMs and GSCs with high tGAS, an indicator for tGLI1 transcriptional activity. Of note, the classification of GBM into distinct subtypes was first reported by Phillips et al. in 2006 with three distinct subtypes (3), while a more recently study in 2010 by Verhaak et al. classified GBM into four distinct subtypes (4). Both studies identified a common subtype named the mesenchymal subtype according to the expression of genes associated with a mesenchymal cell phenotype. Notably, several earlier studies identified mediators and markers for the mesenchymal subtype of GBM and GSCs. For example, RTVP-1 was found to express at a higher level in mesenchymal GBM associated with tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome (28). RTVP-1 overexpression induced mesenchymal differentiation of human neural stem cells, whereas silencing RTVP-1 inhibited the mesenchymal transformation and stemness of GSCs. An important future task is to explore the potential crosstalk between RTVP-1 and tGLI1 in regulating mesenchymal GSCs.

It is also important future task to investigate the potential interactions between tGLI1 and TNF-α/NF-κB in light of the observations that both are enriched in the CD44(+) mesenchymal GSCs and that the proneural GSCs can undergo differentiation to a mesenchymal state in a TNF-α/NF-κB-dependent manner (8,29). Most recently, S100A4 was reported as a novel biomarker of GSCs that is enriched in cells with tumor-initiating and sphere-forming abilities; selective ablation of S100A4-expressing cells blocked tumor growth in vitro and in vivo (30). Whether tGLI1 crosstalks with S100A4, thereby promoting mesenchymal GSCs is unknown but this line of future research is warranted.

Mesenchymal GBM and GSCs are not only more tumorigenic but also more resistant to radiation therapy (8). Given the ability of tGLI1 to promote mesenchymal GBM and GSCs, it is possible that tGLI1-expressing cells are more resistant to radiation therapy. Although the direct role of tGLI1 in radiation resistance has not been reported, it has been shown that tumor cells with hyperactive SHH-GLI1 signaling are more resistant to radiation therapy (31–33). Since tGLI1 functions as a gain-of-function GLI1 and tGLI1 has a higher propensity than GLI1 to promote GSCs in vitro and in vivo, we speculate that tGLI1(+) GSCs are more resistant to radiation therapy compared to GLI1(+) GSCs, which could be tested in future studies.

CD44 is regarded as a marker for cancer stem cells for a number of cancers, including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and GBM (8,34,35) that is associated with tumor initiation and progression (34,36–38). However, emerging evidence suggests that CD44 contributes to the stem cell phenotype via various mechanisms, such as osteopontin signaling and promotion of HIF-2α activity (39). However, transcriptional regulation of CD44 gene is still not well understood. It has been reported that EGR1 transcription factor can induce CD44 expression antigen-stimulated B cells (40). NF-κB has been shown to upregulate CD44 expression in GBM (8) and breast cancer (41). NF-κB cooperates with AP-1 to bind to a cis-element of the CD44 promoter, leading to CD44 expression in breast cancer in a cell type-specific manner (42). Y-box binding protein-1 transcription factor induces CD44 expression in breast cancers (43). Surprisingly, FOXO3 tumor suppressor has been shown to induce CD44 expression in pancreatic cancer (44). Our discovery that tGLI1 directly activates CD44 gene expression sheds important new light into the molecular mechanisms contributing to high CD44 expression in GSCs and possibly cancer stem cells in other tumor types.

Our present and previous studies uncovered that tGLI1 is expressed in a tumor-specific fashion in GBM and breast cancer (13,15–17,19). Expression of tGLI1 in malignant gliomas (21) and breast cancer (20) has been confirmed by other groups. Interestingly, a recent study detected tGLI1 in metastatic hepatoma cells (22). The mechanisms for the tumor-specific expression of tGLI1 are, however, still not elucidated. Since the splicing machinery is highly dysregulated in cancers (45), it is likely that the splicing factors that synthesize tGLI1 are aberrantly overexpressed in GBM, breast cancer, and metastatic hepatomas. Identification of these splicing factors constitutes an important task that could lead to strategies that inhibit tumor progression through inhibiting tGLI1 production.

Evidence from our laboratory and those of other groups suggests that tGLI1 may be regarded as novel therapeutic target for multiple cancer types (13,15–17,19,20,22,46). This notion is supported by the observations that tGLI1 is expressed tumor specifically and that tGLI1 plays an important role in tumor growth, angiogenesis and cancer stem cell renewal. We further speculate that targeting tGLI1, rather than GLI1, could minimize normal tissue toxicity because tGLI1 is only detected in cancer tissues whereas GLI1 is expressed in both cancerous and normal tissues. Smoothened inhibitors can inhibit both tGLI1 and GLI1; however, their efficacy is only modest in GBM and breast cancer due to their inability to suppress non-canonical smoothened-independent activation of tGLI1 and GLI1 (47). Our study provides novel insights into the biology of GBM and GSCs, particularly those belonging to the mesenchymal subtype, defines tGLI1 as a novel mediator of GBM growth and GSC self-renewal, and establishes tGLI1 as a novel transcriptional activator of CD44.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: NIH R01-NS087169 (H.-W. Lo); NIH P30-CA012197(B.C. Pasche), NIH R01NS087169-3S1 (H.-W. Lo and S.R. Sirkisoon), T32CA079448 (R.L. Carpenter), and DoD W81XWH-17-1-0044 (H.-W. Lo).

We thank Drs. Erik Sulman and Krishna Bhat at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for gifting us the GSC cells. We also acknowledge the financial support from the NIH; R01NS087169 (H.-W. Lo), T32CA079448 (R.L. Carpenter), R01NS087169-3S1 (H.-W. Lo and S.R. Sirkisoon), P30CA012197 (B.C. Pasche), and from the DoD, W81XWH-17-1-0044 (H.-W. Lo).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kumthekar PU, Macrie BD, Singh SK, Kaur G, Chandler JP, Sejpal SV. A review of management strategies of malignant gliomas in the elderly population. American Journal of Cancer Research. 2014;4:436–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro-Oncology. 2013;15:ii1–ii56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, Forrest WF, Soriano RH, Wu TD, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:157–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhaak RGW, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. An integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR and NF1. Cancer cell. 2010;17:98. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colman H, Zhang L, Sulman EP, McDonald JM, Shooshtari NL, Rivera A, et al. A multigene predictor of outcome in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12:49–57. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lathia JD, Mack SC, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, Valentim CLL, Rich JN. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes & Development. 2015;29:1203–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.261982.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stopschinski BE, Beier CP, Beier D. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells--from concept to clinical application. Cancer Lett. 2013;338:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhat KP, Balasubramaniyan V, Vaillant B, Ezhilarasan R, Hummelink K, Hollingsworth F, et al. Mesenchymal differentiation mediated by NF-kappaB promotes radiation resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:331–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao P, Joshi K, Li J, Kim SH, Li P, Santana-Santos L, et al. Mesenchymal glioma stem cells are maintained by activated glycolytic metabolism involving aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8644–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221478110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mooney KL, Choy W, Sidhu S, Pelargos P, Bui TT, Voth B, et al. The role of CD44 in glioblastoma multiforme. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2016;34:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement V, Sanchez P, de Tribolet N, Radovanovic I, Ruiz i Altaba A. HEDGEHOG-GLI1 Signaling Regulates Human Glioma Growth, Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal, and Tumorigenicity. Current Biology. 2007;17:165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stecca B, Ruiz IAA. Context-dependent regulation of the GLI code in cancer by HEDGEHOG and non-HEDGEHOG signals. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2:84–95. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo HW, Zhu H, Cao X, Aldrich A, Ali-Osman F. A novel splice variant of GLI1 that promotes glioblastoma cell migration and invasion. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6790–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao X, Geradts J, Dewhirst M, Lo H-W. Upregulation of VEGF-A and CD24 Gene Expression by the tGLI1 Transcription Factor Contributes to the Aggressive Behavior of Breast Cancer Cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:104–15. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter RL, Paw I, Zhu H, Sirkisoon S, Xing F, Watabe K, et al. The gain-of-function GLI1 transcription factor TGLI1 enhances expression of VEGF-C and TEM7 to promote glioblastoma angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:22653–65. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han W, Carpenter RL, Lo H-W. TGLI1 Upregulates Expression of VEGFR2 and VEGF-A, Leading to a Robust VEGF-VEGFR2 Autocrine Loop and Cancer Cell Growth. Cancer Hallmarks. 2013;1:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu H, Carpenter RL, Han W, Lo H-W. The GLI1 Splice Variant TGLI1 Promotes Glioblastoma Angiogenesis and Growth. Cancer letters. 2014:343. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter RL, Lo HW. Hedgehog pathway and GLI1 isoforms in human cancer. Discov Med. 2012;13:105–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao X, Geradts J, Dewhirst MW, Lo HW. Upregulation of VEGF-A and CD24 gene expression by the tGLI1 transcription factor contributes to the aggressive behavior of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:104–15. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Mauro C, Rosa R, D’Amato V, Ciciola P, Servetto A, Marciano R, et al. Hedgehog signalling pathway orchestrates angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancers. British journal of cancer. 2017;116:1425–35. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gricius Dovydas, Kazlauskas A. Analysis of oncogene GLI1 protein expression levels between differing grades of astrocytoma. BIOLOGIJA. 2014;60:142–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan YH, Ding J, Nguyen S, Liu XJ, Xu G, Zhou HY, et al. Aberrant hedgehog signaling is responsible for the highly invasive behavior of a subpopulation of hepatoma cells. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz i Altaba A. Hedgehog signaling and the Gli code in stem cells, cancer, and metastases. Science signaling. 2011;4:pt9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debinski W, Gibo DM. Fos-Related Antigen 1 Modulates Malignant Features of Glioma Cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2005;3:237–49. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferluga S, Tomé CML, Herpai DM, D’Agostino R, Debinski W. Simultaneous targeting of Eph receptors in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:59860–76. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langlois B, Saupe F, Rupp T, Arnold C, van der Heyden M, Orend G, et al. AngioMatrix, a signature of the tumor angiogenic switch-specific matrisome, correlates with poor prognosis for glioma and colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2014;5:10529–45. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelloski CE, Mahajan A, Maor M, Chang EL, Woo S, Gilbert M, et al. YKL-40 expression is associated with poorer response to radiation and shorter overall survival in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3326–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giladi ND, Ziv-Av A, Lee HK, Finniss S, Cazacu S, Xiang C, et al. RTVP-1 promotes mesenchymal transformation of glioma via a STAT-3/IL-6-dependent positive feedback loop. Oncotarget. 2015;6:22680–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SH, Ezhilarasan R, Phillips E, Gallego-Perez D, Sparks A, Taylor D, et al. Serine/Threonine Kinase MLK4 Determines Mesenchymal Identity in Glioma Stem Cells in an NF-kappaB-dependent Manner. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow KH, Park HJ, George J, Yamamoto K, Gallup AD, Graber JH, et al. S100A4 is a biomarker and regulator of glioma stem cells that is critical for mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2017 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Wu K, Gao D, Zhu G, Wu D, Wang X, et al. Reciprocal regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha and GLI1 expression associated with the radioresistance of renal cell carcinoma. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014;90:942–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gan GN, Eagles J, Keysar SB, Wang G, Glogowska MJ, Altunbas C, et al. Hedgehog signaling drives radioresistance and stroma-driven tumor repopulation in head and neck squamous cancers. Cancer Res. 2014;74:7024–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen YJ, Lin CP, Hsu ML, Shieh HR, Chao NK, Chao KS. Sonic hedgehog signaling protects human hepatocellular carcinoma cells against ionizing radiation in an autocrine manner. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2011;80:851–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jijiwa M, Demir H, Gupta S, Leung C, Joshi K, Orozco N, et al. CD44v6 Regulates Growth of Brain Tumor Stem Cells Partially through the AKT-Mediated Pathway. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e24217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF, Zhang L, Adsay V, et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:1030–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourguignon LYW, Peyrollier K, Xia W, Gilad E. Hyaluronan-CD44 Interaction Activates Stem Cell Marker Nanog, Stat-3-mediated MDR1 Gene Expression, and Ankyrin-regulated Multidrug Efflux in Breast and Ovarian Tumor Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:17635–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800109200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breyer R, Hussein S, Radu DL, Putz KM, Gunia S, Hecker H, et al. Disruption of intracerebral progression of C6 rat glioblastoma by in vivo treatment with anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:140–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.1.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prince ME, Sivanandan R, Kaczorowski A, Wolf GT, Kaplan MJ, Dalerba P, et al. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:973–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pietras A, Katz AM, Ekstrom EJ, Wee B, Halliday JJ, Pitter KL, et al. Osteopontin-CD44 signaling in the glioma perivascular niche enhances cancer stem cell phenotypes and promotes aggressive tumor growth. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:357–69. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maltzman JS, Carman JA, Monroe JG. Role of EGR1 in regulation of stimulus-dependent CD44 transcription in B lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2283–94. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith SM, Lyu YL, Cai L. NF-kappaB affects proliferation and invasiveness of breast cancer cells by regulating CD44 expression. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith SM, Cai L. Cell specific CD44 expression in breast cancer requires the interaction of AP-1 and NFkappaB with a novel cis-element. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.To K, Fotovati A, Reipas KM, Law JH, Hu K, Wang J, et al. Y-box binding protein-1 induces the expression of CD44 and CD49f leading to enhanced self-renewal, mammosphere growth, and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2840–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumazoe M, Takai M, Bae J, Hiroi S, Huang Y, Takamatsu K, et al. FOXO3 is essential for CD44 expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:2643–54. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biamonti G, Catillo M, Pignataro D, Montecucco A, Ghigna C. The alternative splicing side of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;32:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gricius D, Kazlauskas A. Analysis of oncogene GLI1 protein expression levels between differing grades of astrocytoma. BIOLOGIJA. 2014;60:142–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimkus TK, Carpenter RL, Qasem S, Chan M, Lo HW. Targeting the Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: Review of Smoothened and GLI Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2016:8. doi: 10.3390/cancers8020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.