Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of high intensity (HI) versus low-to-moderate intensity (LMI) exercise on physical fitness, fatigue, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in cancer survivors.

Methods

Two hundred seventy-seven cancer survivors participated in the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study and were randomized to 12 weeks of HI (n = 139) or LMI exercise (n = 138) that had similar exercise types, durations, and frequencies, but different intensities. Measurements were performed at baseline (4–6 weeks after primary treatment), and 12 (i.e., short term) and 64 (i.e., longer term) weeks later. Outcomes included cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength, self-reported fatigue, HRQoL, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and societal costs. Linear mixed models were conducted to study (a) differences in effects between HI and LMI exercise at longer term, (b) within-group changes from short term to longer term, and (c) the cost-effectiveness from a societal perspective.

Results

At longer term, intervention effects on role (β = 5.9, 95% CI = 0.5; 11.3) and social functioning (β = 5.7, 95%CI = 1.7; 9.6) were larger for HI compared to those for LMI exercise. No significant between-group differences were found for physical fitness and fatigue. Intervention-induced improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and HRQoL were maintained between weeks 12 and 64, but not for fatigue. From a societal perspective, the probability that HI was cost-effective compared to LMI exercise was 0.91 at 20,000€/QALY and 0.95 at 52,000€/QALY gained, mostly due to significant lower healthcare costs in HI exrcise.

Conclusions

At longer term, we found larger intervention effects on role and social functioning for HI than for LMI exercise. Furthermore, HI exercise was cost-effective with regard to QALYs compared to LMI exercise.

Trial registration

This study is registered at the Netherlands Trial Register [NTR2153 [http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctview.asp?TC=2153]] on the 5th of January 2010.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Exercise is recommended to be part of standard cancer care, and HI may be preferred over LMI exercise.

Keywords: Exercise intensity, Neoplasms, Physical fitness, Fatigue, Quality of life, Cost-effectiveness

Introduction

Supervised exercise can contribute to counteracting the negative side effects of cancer and its treatments [1]. Systematic reviews demonstrated safety and beneficial effects of exercise on physical fitness [2], fatigue [3], and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [4], during and after cancer treatment. However, previous studies predominantly reported short-term effects [4, 5]. The few studies that included a longer-term follow-up (≥ 6 months) showed that the benefits of exercise were maintained for HRQoL [4], but not for fatigue [5]. For other outcomes (e.g., physical fitness), longer-term effects are unclear. Therefore, more research on the longer-term effectiveness of exercise in cancer survivors is warranted.

As resources are scarce, decisions on the implementation of healthcare programs are guided not only by their health effects but also by their additional costs in relation to these effects (i.e., cost-effectiveness). Therefore, it is important that state-of-the-art cost-effectiveness analyses of healthcare programs are performed [6]. Cost-effectiveness analyses of exercise interventions in cancer survivors are scarce [7, 8]. A systematic review compared exercise interventions to usual care in patients with various diseases, including cancer, found acceptable incremental cost-effectiveness ratios or cost savings [7]. Similar results were found by a systematic review evaluating the cost-effectiveness of multidimensional cancer rehabilitation programs [8]. However, despite the fair methodological quality of the reviewed studies, the heterogeneity across interventions hampered solid conclusions about their cost-effectiveness.

The present study reports the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the randomized controlled Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study at longer term (i.e., 64 weeks) [9]. At short term (i.e., 12 weeks), high intensity (HI) and low-to-moderate intensity (LMI) exercise interventions significantly improved cardiovascular fitness and HRQoL and reduced fatigue compared to a wait list control (WLC) group, with some indication for a dose-response relationship for exercise intensity on cardiorespiratory fitness [9]. Also, HI and LMI exercise were equally beneficial in counteracting fatigue [9]. This study aimed to evaluate the longer-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HI versus LMI exercise for physical fitness, fatigue, and HRQoL.

Methods

Setting and participants

Detailed methods, including sample size calculations, of the REACT study have been reported previously [9, 10]. Briefly, REACT is a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) in cancer patients recruited from nine Dutch hospitals between 2011 and 2013. The Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Centre approved the study. Patients aged ≥ 18 years with histologically confirmed breast, colon, ovarian, cervix or testis cancer, or lymphomas with no indication of recurrent or progressive disease who had completed (neo-)adjuvant chemotherapy with curative intent were eligible and invited to participate. Exclusion criteria were the following: being unable to perform daily activities; presence of cognitive disorders, severe emotional instability, and diseases that hamper patients’ capacity of carrying out HI exercise; and being unable to read and write Dutch. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Randomization

Following baseline assessments, participants were stratified by cancer type and hospital and randomly assigned to HI exercise, LMI exercise, or WLC using random numbers tables [9]. Shortly after randomization, HI and LMI participants commenced their 12-week exercise program. WLC participants were also randomly allocated to HI or LMI exercise, but started exercising after the 12-week follow-up assessment. Allocation sequence was concealed from the clinical and research staff. Due to the interventions’ nature, participants and physiotherapists were not blinded.

Exercise interventions

HI and LMI exercise interventions had similar exercise types, durations, and frequencies, but differed in intensity (Table 1). Exercise sessions were given twice per week during 12 weeks and supervised by a trained physiotherapist. Both exercise programs included six resistance exercises targeting large muscle groups (i.e., vertical row, leg press, bench press, pull over, abdominal crunch, and lunge), with a training volume of two sets of ten repetitions [10]. Workload per exercise was defined by an indirect one-repetition maximum (1-RM) measurement. Following a warm-up, the physiotherapist estimated a workload at which the patient was expected to perform four to eight repetitions, taking into consideration age, gender, and height [10]. Furthermore, both programs included two types of endurance interval exercises. During weeks 1–4, patients cycled 2 × 8 min with alternating workloads (defined by the maximum short exercise capacity (MSEC) estimated by the steep ramp test [11]). Patients in the HI exercise group alternated 30 s at 65% of MSEC with 60 s at 30% of MSEC. From the fifth week onwards, the 30 s at 65% of MSEC was alternated with 30 s at 30% of MSEC. The workload for the LMI exercise group alternated between 45 and 30% of MSEC in a similar way. During weeks 5–12, one additional endurance interval session was added substituting one 8-min interval of cycling. This interval session consisted of 3 × 5 min of aerobic exercise at constant workload (defined by the heart rate reserve using the Karvonen formula) [12]. The use of the Karvonen formula allowed patients to perform these aerobic exercises using different ergometers (e.g., cycle ergometer, treadmill). Physiotherapists applied behavioral motivational counseling techniques to overcome possible exercise barriers and to encourage participants to obtain and maintain a physically active lifestyle. At 4, 10, and 18 weeks after intervention completion, three booster sessions (i.e., supervised workout sessions) were provided to motivate participants to maintain their exercise engagements.

Table 1.

Exercise intensities of the HI and LMI resistance and endurance exercise programs

| Resistance exercises (1-RM)a (6 exercises targeting the large muscle groupsb, 2 sets of 10 repetitions each) |

Endurance interval exercises Part A (MSEC)a (8 min alternating workload) |

Endurance interval exercises Part B (HRR)a (3 × 5 min constant workload) |

Counseling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High intensity (HI) exercise c | 70–85% | 65/30%d | ≥ 80% | Participants were encouraged to start or maintain a physically active lifestyle in addition to the supervised exercise sessions. |

| Low-to-moderate intensity (LMI) exercise c | 40–55% | 45/30%d | 40–50% |

1-RM, one-repetition maximum; MSEC, maximum short exercise capacity; HRR, heart rate reserve;

aEvery 4 weeks (week 1, 5 and 9), the physiotherapist evaluated training progress and adjusted the workload accordingly

bExercises included vertical row, leg press, bench press, pull over, abdominal crunch, and lunge)

cExercises were accompanied with BORG scores and heart rate monitors to guide the physiotherapists. In the occasion that the training intensity seemed too high or too low, the 1-RM, MSEC, or HRR was reassessed

dIn the first four weeks, 30 s at 65% of MSEC was alternated with 60 s at 30% for HI, and from the fifth week onwards, intensity was alternated every 30 s. The workload for the LMI exercise group was alternated between 45 and 30% of MSEC in a similar way

Measurements

Socio-demographic data were collected by self-report. Clinical information was obtained from medical records. Physiotherapists documented session attendance in exercise logs. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, and after 12 and 64 weeks, except for dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which was only performed at baseline and 64 weeks. Detailed descriptions of the assessments and their measurement properties are provided elsewhere [10, 13]. Physical tests were performed by an independent assessor.

Primary outcomes

Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured during a maximal cyclometer exercise test aiming to achieve peak oxygen uptake (peakVO2, in mL/kg/min) within 8–12 min [14] following a ramp protocol, in which breath-by-breath gas exchange was measured continuously. After each test, peakVO2 (i.e., highest oxygen consumption values averaged over a 15-s interval within the last 60 s), peak power output (peakW, in watt), and the ventilatory threshold (determined by the oxygen equivalent method [14]) were recorded. Hand-grip strength was assessed using a JAMAR hand-grip dynamometer [15] and the mean score (in kg) of three attempts with the participants’ dominant hand was used for further analyses. Lower body function was assessed using the 30-s chair-stand test [16]. The total number of times participants raised to a full stand in 30 s was reported. Fatigue was assessed using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) [17], including five subscales: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced physical activity, reduced motivation, and mental fatigue.

Secondary outcomes

HRQoL was measured using the European Organisation Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) [18] and anxiety and depression by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [19]. Physical activity (PA) was objectively assessed by accelerometers (Actigraph) using vertical accelerations converted into counts/minute. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured body height and weight. Body composition was determined using percentage of total body fat mass (%FM), lean mass (%LM), and lumbar spine (L1–L4) bone mineral density (BMD), measured by DXA with a Hologic Discovery DXA scanner. Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were estimated using the EQ-5D-3L [20]. EQ-5D-3L health states were converted into utilities using the Dutch tariff [21]. QALYs were calculated using linear interpolation between measurement points.

Cost measures

Intervention costs were micro-costed [22, 23]. Attendance of exercise and booster sessions were registered, intervention providers’ time investments were valued using their gross hourly salaries (including overhead), and material costs were estimated using invoices. All other cost categories were assessed using 3-monthly questionnaires, with 3-month recall periods. Healthcare costs included costs due to primary and secondary healthcare use, and medication. Dutch standard costs were used to value healthcare use [23]. Medication use was valued using unit prices of the Royal Dutch Society of Pharmacy [24]. Informal care (i.e., care by family/friends) was valued using a shadow price [23]. Absenteeism was assessed using participants’ reports of their number of absence days and, in case of partial absence, their percentage of normal working hours worked. Using the friction cost approach (FCA), absenteeism costs were valued with age- and gender-specific price weights [23, 25]. The FCA assumes that costs are limited to the friction period (i.e., period needed to replace a sick-listed worker = 23 weeks) [23, 25]. Unpaid productivity (e.g., volunteer work) losses were valued using the aforementioned shadow price [23]. Sports costs included expenses on memberships and equipment. All costs were converted to 2012 euros (€) [26].

Statistical analyses

Differences in outcomes between HI and LMI exercise interventions at longer-term follow-up were assessed using linear mixed model analyses with a two-level structure (i.e., participants were clustered within hospitals). Both interventions were simultaneously regressed on the longer-term value of the outcome, adjusted for the baseline value, age, gender, and timing of intervention (i.e., direct start or WLC). To check whether missing data affected the results, sensitivity analyses were conducted on an imputed dataset for peakVO2, hand-grip strength, and fatigue (SA1). Missing data were multiple imputed using predictive mean matching, stratified by group allocation [27]. The imputation model was specified according to White et al. [27]. Twenty different datasets were created. Pooled estimates were calculated using Rubin’s rules [27].

To evaluate within-group changes in HI and LMI exercise interventions from short-term to longer-term follow-up, we conducted linear mixed models for repeated measurements (i.e., repeated measurements were clustered within patients, which were clustered within hospitals). This model simultaneously regressed the intervention effect on short term and longer term and included time and the interaction between time and exercise group as determinants and age, gender, and the outcome’s baseline value as covariates.

Cost-effectiveness analyses were performed from the societal perspective using the multiple imputed datasets [27]. Between-group differences were estimated for total and disaggregated costs. Total cost and effect differences were estimated using linear mixed model analyses, adjusted for baseline, age, gender, and intervention timing. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated by dividing the adjusted total cost differences by those in effects [6]. Uncertainty around cost differences and ICERs was estimated using bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap intervals (5000 replications, stratified by hospital) [28]. Cost-effectiveness planes [29] and cost-effectiveness acceptability (CEA) curves were constructed [30]. A post hoc analysis was performed applying a healthcare perspective and a sensitivity analysis (SA2) was conducted assuming that all scheduled exercise sessions needed to be paid for, rather than only those attended.

As disease recurrence—which may influenced quality of life and healthcare costs—occurred more often during follow-up in LMI exercise, additional sensitivity analyses (SA3–4) were performed. We excluded patients with disease recurrence (n = 17) in order to check whether disease recurrence affected the results of the main effectiveness (i.e., between-group difference—SA3) and cost-effectiveness analyses (SA4).

All primary analyses were performed according to intention-to-treat. Costs and effects beyond 1 year were discounted at a rate of 4 and 1.5%, respectively [23]. Effectiveness analyses were performed in SPSS (v22.0) and multiple imputation and cost-effectiveness analyses in STATA (v12.0). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

At present, raw data of the REACT study forms part of a PhD project, including current data on long-term (cost-)effectiveness. As a consequence, currently, we are unable to publish this dataset. However, the REACT dataset is included in the internationally shared POLARIS database [31], and researchers who are interested to collaborate are invited to prepare a paper proposal.

Results

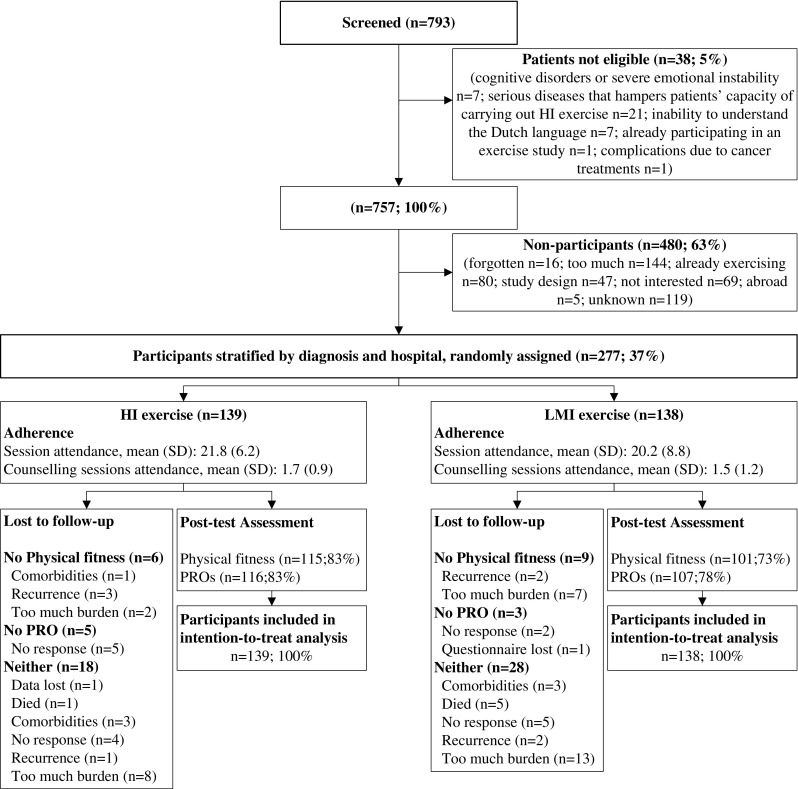

Of the 757 eligible patients, 277 (37%) participated (Fig. 1). Age, gender, and cancer type did not differ significantly between participants and non-participants [9]. The participants’ baseline characteristics were balanced across groups (Table 2). On average, participants in HI and LMI groups attended 20.2 (SD = 8.8) and 21.8 (SD = 6.2) of 24 exercise sessions and 1.5 (SD = 1.2) and 1.7 (SD = 0.9) of 3 booster sessions, respectively (Fig. 1). There were no adverse events directly related to the interventions. Complete physical fitness and patient-reported outcome data were obtained from 116 (80%) and 223 (81%) participants, respectively. Furthermore, 211 (76%), 185 (66%), 179 (65%), 173 (63%), and 176 (64%) participants had complete cost data at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Patients flowchart of the REACT study. HI, high intensity exercise; LMI, low-to-moderate intensity exercise; WLC, wait list control group; PRO, patient-reported outcomes

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

| Characteristics | LMI n = 138 |

HI n = 139 |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | ||

| Age, mean (SD) (years) | 53 (11.4) | 54 (10.7) |

| Gender, n (%) male | 26 (19) | 29 (21) |

| Partner, n (%) yes | 120 (87) | 112 (81) |

| Education, n (%)a | ||

| Low | 19 (14) | 28 (20) |

| Intermediate | 64 (47) | 58 (42) |

| High | 53 (39) | 52 (38) |

| Being employed, n (%) | ||

| Employed | 30 (22) | 36 (26) |

| Not employed | 82 (59) | 85 (61) |

| Retired | 26 (19) | 18 (13) |

| Smoking, n (%) yesb | 8 (6) | 9 (7) |

| Comorbidities ≥ 2, n (%) yes | 14 (10) | 16 (12) |

| Sport history, n (%) yesc | 83 (61) | 72 (52) |

| Exercise during chemotherapy, n (%) yesa | 25 (18) | 27 (20) |

| Clinical | ||

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||

| Breast | 89 (65) | 92 (66) |

| Colon | 24 (17) | 25 (18) |

| Ovarian | 4 (3) | 8 (6) |

| Lymphoma | 16 (12) | 10 (7) |

| Cervix | 4 (3) | 0 |

| Testis | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | ||

| Local | 84 (61) | 103 (74) |

| Advanced | 54 (39) | 36 (26) |

| Type of treatment, n (%) yes | ||

| Surgery | 123 (89) | 127 (91) |

| Radiation therapy | 61 (44) | 74 (53) |

| Surgery + radiation therapy | 58 (42) | 68 (49) |

| Immunotherapy | 36 (26) | 23 (17) |

| Hormonal therapy | 61 (44) | 67 (48) |

| Type of chemotherapy, n (%) | ||

| TAC | 47 (34) | 56 (40) |

| FEC | 9 (7) | 10 (7) |

| TAC/FEC combinations | 30 (22) | 23 (17) |

| Capecitabine and oxaliplatin | 14 (10) | 12 (9) |

| Oxaliplatin combinations | 10 (7) | 12 (9) |

| Carboplatin and paclitaxel | 8 (6) | 10 (7) |

| CHOP | 11 (8) | 7 (5) |

| ABVD | 4 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Cisplantin | 3 (2) | 0 |

| BEP | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

n number; FEC fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide; TAC taxotere, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide; CHOP cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; ABVD doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BEP bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin

an − 3

bn − 4

cn − 1

At longer term, intervention effects on role functioning (βbetween-group difference = 5.9, 95% CI = 0.5; 11.3) and social functioning (βbetween-group difference = 5.7, 95% CI = 1.7; 9.6) were larger for HI than for LMI exercise (Table 3). No other significant between-group differences were found at longer term. Results of the sensitivity analyses (SA3) were comparable (data not shown).

Table 3.

Mean (SD) values at baseline and follow-up and differences in effects on primary and secondary outcomes between groups (adjusted model, corrected for age and gender)

| LMI (n = 138) | 64 weeks follow-up | HI (n = 139) | 64 weeks follow-up | HI vs. LMI | HI vs. LMIa | ∆Time LMI | ∆Time HI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Baseline | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Cardiorespiratory fitnessb | ||||||||

| PeakVO2 (mL/kg/min) | 22.1 (5.8) | 25.6 (6.8) | 22.0 (6.5) | 26.3 (8.1) | 0.7 (− 0.3; 1.7) | 0.5 (− 0.9; 1.9) | 0.1 (− 0.8; 0.9) | − 0.5 (− 1.3; 0.3) |

| WMax (W) | 136 (43) | 155 (48) | 137 (45) | 162 (55) | 6.4 (0.6; 12.3)* | 2.2 (− 1.6; 5.9) | 1.8 (− 1.8; 5.4) | |

| Anaerobic threshold (mL/kg/min) | 16.1 (4.6) | 18.0 (5.2) | 15.9 (4.9) | 18.5 (5.7) | 0.6 (− 0.4; 1.6) | − 0.7 (− 1.6; 0.1) | − 1.1 (− 1.9; − 0.2)* | |

| Muscle strength | ||||||||

| Sit to stand (stands)c | 16 (3.7) | 20 (5.2) | 17 (4.2) | 20 (5.2) | − 0.4 (− 1.4; 0.5) | 1.2 (0.5; 1.9)* | 1.4 (0.7; 2.2)* | |

| Hand-grip strength (kg)d | 33.2 (9.5) | 35.9 (11.0) | 32.8 (10.0) | 35.6 (11.4) | − 0.4 (− 1.6; 0.8) | − 0.2 (− 2.1; 1.8) | 0.1 (− 0.7; 0.9) | 1.4 (0.6; 2.2)* |

| Fatigue (range 1–20)e | ||||||||

| General fatiguef | 12.9 (4.2) | 11.7 (1.3) | 12.7 (3.8) | 11.7 (1.6) | − 0.1 (− 0.4; 0.3) | − 0.2 (− 0.6; 0.3) | 1.5 (0.7; 2.3)* | 2.0 (1.2; 2.6)* |

| Physical fatiguef | 12.8 (4.0) | 13.0 (1.4) | 12.9 (3.9) | 12.8 (1.6) | − 0.2 (− 0.6; 0.1) | 3.8 (3.0; 4.6)* | 4.1 (3.3; 4.8)* | |

| Reduced activityg | 11.7 (3.5) | 12.5 (1.2) | 12.0 (3.5) | 12.4 (1.5) | − 0.1 (− 0.5; 0.3) | 3.5 (2.7; 4.2)* | 3.0 (2.3; 3.7)* | |

| Reduced motivationh | 8.7 (3.1) | 12.1 (1.7) | 9.0 (3.0) | 12.1 (1.8) | 0.02 (− 0.4; 0.5) | 3.7 (3.0; 4.4)* | 4.6 (3.9; 5.2)* | |

| Mental fatiguef | 10.8 (4.1) | 11.8 (1.1) | 11.0 (4.0) | 11.7 (1.4) | − 0.03 (− 0.3; 0.3) | 1.8 (1.0; 2.6)* | 2.1 (1.3; 2.9)* | |

| Health-related quality of life (range 0–100)i | ||||||||

| Global QoL | 73.2 (16.7) | 80.0 (16.5) | 71.3 (15.8) | 83.0 (15.6) | 3.7 (− 0.3; 7.7)† | 0.7 (− 2.7; 4.0) | 0.4 (− 2.9; 3.7) | |

| Physical functioning | 82.1 (12.9) | 87.6 (14.8) | 80.4 (15.3) | 89.7 (11.9) | 2.9 (− 0.1; 5.9)† | − 0.4 (− 2.8; 1.9) | 2.2 (− 0.1; 4.5)† | |

| Role functioning | 70.9 (25.1) | 83.5 (24.5) | 68.5 (26.7) | 88.8 (19.4) | 5.9 (0.5; 11.3)* | 1.1 (− 4.2; 6.3) | 5.5 (0.3; 10.6)* | |

| Emotional functioning | 83.5 (16.3) | 85.3 (18.1) | 85.4 (16.5) | 87.4 (17.4) | 0.9 (− 2.8; 4.6) | 1.0 (− 2.4; 4.3) | − 0.8 (− 4.1; 2.4) | |

| Cognitive functioning | 77.7 (23.0) | 83.8 (17.9) | 79.5 (21.6) | 83.9 (21.2) | − 0.7 (− 4.8; 3.4) | 5.7 (2.0; 9.4)* | 2.1 (− 1.6; 5.7) | |

| Social functioning | 78.8 (21.3) | 87.2 (19.0) | 76.7 (24.1) | 92.2 (15.5) | 5.7 (1.7; 9.6)* | 1.1 (− 2.6; 4.8) | − 0.5 (− 1.3; 0.3) | |

| Distress (range 0–21)j | ||||||||

| Anxietyh | 3.9 (2.8) | 3.9 (3.1) | 3.8 (3.0) | 3.9 (3.5) | 0.2 (− 0.4; 0.9) | − 0.1 (− 0.7; 0.6) | 0.7 (0.1; 1.3)* | |

| Depressionk | 3.1 (2.8) | 2.8 (3.3) | 3.2 (2.7) | 2.6 (3.0) | − 0.3 (− 0.9; 0.4) | 0.1 (− 0.5; 0.6) | 0.1 (− 0.4; 0.7) | |

| Body composition | ||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 (4.3) | 26.9 (4.5) | 26.9 (4.5) | 27.0 (4.6) | − 0.02 (− 0.4; 0.4) | 0.1 (− 0.2; 0.3) | 0.3 (0.03; 0.5)* | |

| Percentage fat massl | 31.7 (7.4) | 33.5 (7.4) | 32.1 (6.9) | 33.1 (8.3) | − 0.7 (− 1.7; 0.3) | |||

| Percentage lean mass | 64.6 (7.5) | 63.5 (7.0) | 64.9 (6.5) | 63.3 (9.2) | − 0.4 (− 1.7; 0.9) | |||

| BMD lumbar spine (g/cm2)m | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | − 0.01 (− 0.02; 0.01) | |||

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Accelerometer (CPM)n,o | 254.0 (96.1) | 243.4 (165.4) | 243.7 (100.4) | 217.9 (139.9) | − 22.4 (− 65.3; 20.5) | − 21.9 (− 61.8; 17.9) | − 26.3 (− 65.6; 13.0) | |

LMI, low-to-moderate-intensity exercise; HI, high-intensity exercise; SD, standard deviation; n, number; kg, kilogram; W, watt; BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density; CPM, counts per minute

*p < 0.05); †0.05 ≤ p < 0.10

aSensitivity analysis imputed dataset

bMissings due to technical problems (n = 2), or discomfort (n = 1)

cMissings due to musculoskeletal problems (n = 3)

dMissings due to musculoskeletal problems (n = 11)

eHigher score means a higher level of self-reported fatigue in all subscales

fMissing due to incomplete questionnaire (n = 2)

gMissing due to incomplete questionnaire (n = 1)

hMissing due to incomplete questionnaire (n = 3)

iHigher score means a higher level of self-reported HRQoL in all subscales

jHigher score means a higher level of anxiety and depression in both subscales

kMissing due to incomplete questionnaire (n = 8)

lMissings due to no show (n = 2)

mMissings due to no show (n = 2) or technical problems (n = 2)

nAverage counts for Y-axis

oMissings due to technical problems/insufficient wearing-time (n = 37)

No significant within-group changes were found for peakVO2 and HRQoL between short and longer terms for both HI and LMI exercise interventions, indicating that the intervention-induced improvements at short term were maintained at longer term (Table 3). For HI exercise, role functioning (βwithin-group change = 5.5, 95% CI = 0.3; 10.6), hand-grip strength (βwithin-group change = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.6; 2.2), and BMI (βwithin-group change = 0.3, 95% CI = 0.03; 0.5) increased from short to longer term, and lower body muscle function increased both in HI and LMI exercise interventions (HI—βwithin-group change = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.7; 2.2, LMI—βwithin-group change = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.5; 1.9). For both groups, significant within-group changes were found for fatigue and anxiety, such that they returned to baseline levels. No significant within-group changes from short to longer term were found for depression and objectively measured PA.

Total societal costs did not differ significantly between HI and LMI exercise interventions (β = − 2429€, 95% CI = − 5798; 933). In HI exercise, healthcare costs were significantly lower (β = − 2056€, 95% CI = − 3816; − 443) and intervention costs were significantly higher (β = 40€, 95% CI = 8; 75) than in LMI exercise (Table 4). For QALYs, an ICER of − 87,831 was found, indicating that HI exercise was associated with a cost saving of 87,831€/QALY gained, compared with LMI exercise (Table 5). When societal decision-makers are not willing to pay anything per unit of effect gained, the probability of HI exercise being cost-effective compared with LMI exercise was 0.87. This probability increased to 0.91 at a willingness-to-pay of 20,000€/QALY and reaching 0.95 at 52,000€/QALY. For hand-grip strength, the probability of cost-effectiveness increased as the willingness-to-pay increased, from 0.87 to 0.95 at 58.000€/kg, while it decreased for peakVO2 and general fatigue (data not shown). From a healthcare perspective, results were more favorable for HI exercise as shown by higher probabilities of cost-effectiveness, e.g., if healthcare decision-makers are not willing to pay anything per unit of effect gained, the probability of cost-effectiveness was 0.97 for all outcome measures. When we assumed that all scheduled exercise sessions needed to be paid for SA2, we found comparable results. When patients who had a disease recurrence during follow-up were excluded from the analyses (SA4), the mean difference in total societal costs between HI and LMI exercise interventions was smaller (i.e., − 1366€ versus − 2429€). Additionally, HI exercise had slightly lower probabilities of being cost-effective in comparison with LMI exercise (i.e., 0.89 versus 0.96 at 80,000€/QALY). However, the societal cost difference was in favor of HI exercise, in both the main analysis and SA4, and the differences in effect were comparable.

Table 4.

Mean costs per participant in the high intensity (HI) and low-to-moderate intensity (LMI) exercise groups and cost differences between both groups during follow-up

| Cost category | LMI n = 138; mean (SEM) |

HI n = 139; mean (SEM) |

Mean cost difference Model 1a (95% CI) |

Mean cost difference Model 2b (95% CI) |

Mean cost difference Model 3c (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention costs (€) | 815 (15) | 858 (11) | 43 (8; 77) | 40 (7; 76) | 42 (8; 75) |

| Healthcare costs (€) | 6232 (993) | 4148 (522) | − 2075 (− 3816; − 464) | − 2043 (− 3851; − 438) | − 2056 (− 3816; − 443) |

| Primary care | 2494 (385) | 2127 (384) | − 370 (− 1102; 471) | − 333 (− 1073; 491) | − 342 (− 1056; 493) |

| Secondary care | 2644 (657) | 1515 (226) | − 1121 (− 2237; − 204) | − 1131 (− 2295; − 201) | − 1134 (− 2274; − 200) |

| Medication | 1093 (227) | 505 (75) | − 584 (− 917; − 280) | − 578 (− 915; − 276) | − 584 (− 917; − 268) |

| Informal care costs (€) | 1964 (344) | 2095 (478) | 136 (− 590; 949) | 163 (− 566; 969) | 151 (− 552; 954) |

| Absenteeism costs (€) | 7527 (942) | 6759 (845) | − 696 (− 2630; 1241) | − 523 (− 2462; 1369) | − 523 (− 2450; 1394) |

| Unpaid productivity costs (€) | 264 (35) | 197 (29) | − 67 (− 140; 6) | − 63 (− 137; 8) | − 67 (− 138; 5) |

| Sports costs (€) | 552 (73) | 566 (90) | 18 (− 138; 192) | 25 (− 132; 197) | 26 (− 128; 197) |

| Total costs (€) | 17,355 (1720) | 14,623 (1327) | − 2641 (− 5983; 767) | − 2400 (− 5850; 942) | − 2429 (− 5798; 933) |

€, euro; n, number; CI, confidence interval; SEM, standard error of the mean

aSolely corrected for follow-up duration

bCorrected for follow-up duration, age, and gender

cRandom intercept for hospital and corrected for follow-up duration, age, and gender

Table 5.

Differences in pooled mean costs and effects (95% confidence intervals), incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, and the distribution of incremental cost-effect pairs around the quadrants of the cost-effectiveness planes

| Analysis | Sample size | Outcome | ∆C (95% CI) | ∆E (95% CI) | ICER | Distribution CE-plane (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMI | HI | € | Points | €/point | NE1 | SE2 | SW3 | NW4 | ||

| Main analysis—imputed dataset | 138 | 139 | QALYs (range 0–1) | − 2429 (− 5798; 933) | 0.028 (− 0.006; 0.061) | − 87,831 | 13.2 | 55.3 | 17.7 | 13.8 |

| 138 | 139 | General fatigue (0–20) | − 2429 (− 5798; 933) | − 0.16 (− 0.61; 0.29) | 15,116 | 10.3 | 65.6 | 22.2 | 1.7 | |

| 138 | 139 | Grip strength (kg) | − 2429 (− 5798; 933) | 0.14 (− 1.72; 2.01) | 1411 | 7.6 | 50.3 | 37.6 | 4.5 | |

| 138 | 139 | PeakVO2 (mL/kg/min) | − 2429 (− 5798; 933) | − 0.02 (− 1.40; 1.37) | 159,236 | 5.1 | 42.7 | 45.3 | 7.0 | |

| Post hoc analysis—healthcare perspective | 138 | 139 | QALYs (range 0–1) | − 2015 (− 3786; − 412) | 0.028 (− 0.006; 0.061) | − 72,859 | 1.2 | 93.1 | 5.5 | 0.2 |

| 138 | 139 | General fatigue (0–20) | − 2015 (− 3786; − 412) | − 0.16 (− 0.61; 0.29) | 12,540 | 1.1 | 74.8 | 23.9 | 0.2 | |

| 138 | 139 | Grip strength (kg) | − 2015 (− 3786; − 412) | 0.14 (− 1.72; 2.01) | − 14,096 | 0.7 | 57.1 | 41.5 | 0.6 | |

| 138 | 139 | PeakVO2 (mL/kg/min) | − 2015 (− 3786; − 412) | − 0.02 (− 1.40; 1.37) | 132,093 | 0.6 | 47.1 | 51.5 | 0.7 | |

| Sensitivity analysis—fixed intervention costs | 138 | 139 | QALYs (range 0–1) | − 2471 (− 5849; 907) | 0.028 (− 0.006; 0.061) | − 89,341 | 10.6 | 83.7 | 4.6 | 1.1 |

| 138 | 139 | General fatigue (0–20) | − 2471 (− 5849; 907) | − 0.16 (− 0.61; 0.29) | 15,376 | 10.0 | 65.9 | 22.3 | 1.7 | |

| 138 | 139 | Grip strength (kg) | − 2471 (− 5849; 907) | 0.14 (− 1.72; 2.01) | − 17,285 | 7.4 | 50.5 | 37.8 | 4.4 | |

| 138 | 139 | PeakVO2 (mL/kg/min) | − 2471 (− 5849; 907) | − 0.02 (− 1.40; 1.37) | 161,974 | 5.0 | 42.8 | 45.5 | 6.8 | |

| Sensitivity analysis—patients with disease recurrence excluded (SA4) | 126 | 134 | QALYs (range 0–1) | − 1366 (− 4692; 2063) | 0.025 (− 0.009; 0.059) | − 54,228 | 21.5 | 70.6 | 4.5 | 3.4 |

| 126 | 134 | General fatigue (0–20) | − 1366 (− 4692; 2063) | − 0.18 (− 0.63; 0.26) | 7389 | 21.2 | 58.7 | 16.4 | 3.7 | |

| 126 | 134 | Grip strength (kg) | − 1366 (− 4692; 2063) | 0.16 (− 1.58; 1.90) | − 8517 | 14.2 | 43.0 | 32.1 | 10.7 | |

| 126 | 134 | PeakVO2 (mL/kg/min) | − 1366 (− 4692; 2063) | − 0.03 (− 1.31; 1.25) | 48,349 | 11.8 | 37.1 | 38.0 | 13.2 | |

C, costs; E, effects; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; CE-plane, cost-effectiveness-plane; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years

1Refers to the northeast quadrant of the CE-plane, indicating that high-intensity training is more effective and more costly than low-to-moderate-intensity training

2Refers to the southeast quadrant of the CE-plane, indicating that high-intensity training is more effective and less costly than low-to-moderate-intensity training

3Refers to the southwest quadrant of the CE-plane, indicating that high-intensity training is less effective and less costly than low-to-moderate-intensity training

4Refers to the northwest quadrant of the CE-plane, indicating that high-intensity training is less effective and more costly than low-to-moderate-intensity training

Discussion

At longer term (i.e., 64 weeks), effects on role and social functioning were significantly larger for HI than for LMI exercise. Within-group changes showed that intervention-induced improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and HRQoL found at short term were successfully maintained at longer term for HI and LMI exercise interventions, whereas fatigue returned to baseline levels. Also, HI exercise was cost-effective for QALYs, compared to LMI exercise.

The mean improvements in peakVO2 after exercise (HI 4.3 mL/kg/min, LMI 3.5 mL/kg/min) at longer term were in line with the mean improvement of 3.3 mL/kg/min found in cancer survivors after supervised exercise, as reported in a previous meta-analysis [2]. In contrast with the tendency of a dose-response relationship of exercise intensity at short term [9], no significant differences in peakVO2 were found at longer term between HI and LMI exercise. Nevertheless, the exercise-induced benefits on peakVO2 at short term were successfully maintained over time in both exercise groups. Although this is hopeful, we should acknowledge that, compared to healthy adults, the patients’ level of peakVO2 at longer term was still “poor” [14]. Apparently, a 12-week exercise program is too short for patients to fully recover to normative values. On the other hand, there may be a possibility that patients do not fully recover after having received multiple cancer treatments.

At longer term, hand-grip strength and lower body muscle function were not significantly different between HI and LMI exercise interventions. A previous meta-regression analysis revealed that the effects of resistance training on muscle strength may be more dependent on volume than on intensity [32]. Additional head-to-head comparisons of exercise programs with different exercise parameters (i.e., frequency, intensity, type, time) are therefore warranted to define the optimal exercise dose on muscle strength for cancer survivors. Furthermore, increases in both strength outcomes between short and longer terms for both groups suggest that these improvements result from increased uptake of daily activities during follow-up.

At longer term, self-reported fatigue did not differ significantly between HI and LMI exercise interventions, and in both groups, it returned to baseline values between short and longer terms. This lack of sustainable improvements in fatigue is in line with previous studies [3] and may be related to the patients’ low self-efficacy in managing fatigue, particularly while resuming daily activities without supervision and support from a physiotherapist [33]. On the other hand, self-reported fatigue in a longitudinal study is also susceptible to “response-shift bias,” resulting from a change in the internal standard of fatigue perception throughout the cancer continuum [34].

We found a significant better social and role functioning for HI exercise compared to LMI exercise at longer term. In addition, longer-term effects on global QoL and physical functioning tended to be larger for HI than for LMI exercise, but this was not significant. Overall, current findings reveal a possible dose-response relationship of exercise intensity for some HRQoL domains among cancer survivors. Hence, a previous meta-analysis reported significant exercise effects on global QoL and social functioning, but not on role functioning [4]. Based on our significant effects on role functioning, it may be hypothesized that participants gain confidence from completing a HI exercise program [35], resulting in improvements in a person’s role in society. Furthermore, the exercise-induced benefits on HRQoL were successfully maintained over time in both interventions, despite the return to baseline levels of fatigue. This indicates that besides fatigue, which is found to mediate the exercise effect on HRQoL [36], other factors also contribute to HRQoL.

The lack of a significant difference between HI and LMI exercise interventions in psychological distress at longer term is in contrast with a previous meta-analysis reporting small but significant reductions in depression and anxiety after exercise at short and longer terms, compared to usual care [4, 37]. Yet, our study lacked a non-exercise group and the mean values for both outcomes were already low at baseline, leaving little room for improvement. Furthermore, from short to longer term, anxiety returned to baseline in both groups, despite the beneficial short-term intervention effects on anxiety after HI exercise [9]. So, HI exercise might be more effective in reducing anxiety compared to LMI exercise; however, sustainability is lacking which may reflect the vulnerability of psychosocial recovery [38].

Comparable with our short-term findings [9], there were no significant differences between HI and LMI exercise interventions in body composition and objectively measured PA at the longer term. This may be related to the design of our exercise interventions. To successfully reduce fat mass, complementary dietary changes may be required [39] and improving and maintaining PA may require specific behavioral change techniques (e.g., motivational interviewing [40], goal setting [41]). Our finding that BMI significantly increased from short to longer term in HI exercise is unexpected, and its clinical meaningfulness may be questioned, as it was not supported by changes in %FM and %LM.

At the lower bounds of the Dutch and UK willingness-to-pay threshold (i.e., 20,000 and 24,400€/QALY gained, respectively), the probability of HI exercise being cost-effective compared to that of LMI exercise was ≥ 0.91 and increased even more with increasing willingness-to-pay values. Thus, at longer term, HI exercise can be considered cost-effective compared with LMI exercise for QALYs, if decision-makers are willing to accept a probability of cost-effectiveness of 0.91 and to pay 20,000€/QALY. The relatively high probabilities of cost-effectiveness seemed to be related to lower healthcare costs in HI exercise. Although smaller, the healthcare costs were still lower after excluding patients with disease recurrence, and HI exercise remained cost-effective. Current results support previous results of a systematic review showing acceptable cost-effectiveness ratios for cancer rehabilitation programs that produced significant health gains [8] compared to usual care. As willingness-to-pay thresholds are lacking for peakVO2, hand-grip strength, and general fatigue, strong conclusions about HI’s cost-effectiveness as compared to LMI exercise for these outcomes cannot be made.

Strengths of this study include the direct comparison between HI and LMI exercise interventions, longer-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses, multicentre RCT design, large sample size, the use of valid and reliable outcome measures, and the use of state-of-the-art statistical methods. However, some limitations are noteworthy. First, to limit non-participation and minimize contamination, a WLC was included instead of a non-exercising control group. Therefore, at longer term, we were only able to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HI compared to LMI exercise, because all participants had received an exercise intervention at 64 weeks. Second, cost data were collected using self-report, which may have caused “social desirability” and/or “recall bias.” Third, a relatively large number of participants had missing cost data. To deal with this limitation, missing data were multiple imputed [42]. Finally, it should be acknowledged the CEA results might not be generalized to other countries with different healthcare systems and/or payment structures [43].

Conclusions

In conclusion, at longer-term follow-up, we found a larger intervention effect on role and social functioning for HI than for LMI exercise. Exercise-induced benefits in peakVO2 and HRQoL were successfully maintained between short and longer terms, but not for fatigue. Furthermore, HI exercise was cost-effective for QALYs compared to LMI exercise, mostly due to significant lower healthcare costs in HI exercise. Hence, the current findings advocate the implementation of supervised exercise as part of standard cancer care, and if possible HI exercise.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the A-CaRe Program, http://www.a-care.org. The authors acknowledge the A-CaRe Clinical Research Group and thank all patients who participated in the trial. In addition, we thank the oncologists, nurses, sports physicians and their laboratory staff, rehabilitation specialists, and physical therapists for their support in conducting the trial. Furthermore, the authors would like to acknowledge Astrid Broersen, Eric Buytels, and Lars van Knippenberg for their contribution to the development of the exercise programs. We wish to thank Karen van der Weiden, Charlotte de Kruif, Joep van Kesteren, Michiel Greidanus, and Julie Heeren for their support in patient recruitment and collection and assembly of data.

Abbreviations

- 1-RM

one-repetition maximum

- %FM

percentage of total body fat mass

- %LM

percentage of total lean mass

- BC

bias-corrected

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BMI

body mass index

- CEA

cost-effectiveness acceptability

- DXA

dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

- EORTC-QLQ-C30

European Organisation Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life questionnaire-Core 30

- FCA

friction cost approach

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HI

high intensity

- HRQoL

health-related quality of life

- HRR

heart rate reserve

- ICERs

incremental cost-effectiveness ratios

- LMI

low-to-moderate intensity

- MFI

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

- MSEC

maximum short exercise capacity

- PA

physical activity

- PeakVO2

peak oxygen uptake

- PeakW

peak power output

- QALYs

quality-adjusted life years

- QoL

quality of life

- REACT

Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SA

sensitivity analyses

- WLC

wait list control

Authors’ contributions

CK, WM, GS, JB, MC, and LB designed the study. GS and GV supported patient recruitment and CK, JD, and LB provided study materials. CK, JD, JT, JEB, and LB performed statistical analysis. CK, JD, and LB drafted the manuscript. WM, GS, GV, JT, JEB, JB, and MC critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. WM, MC, and LB gave administrative, technical, and material supports.

Funding

This work was supported by the Alpe d’HuZes/KWF Fund. The research grant is provided by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant Number ALPE2009-4619).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

This study is approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Centre (Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Conflict of interest

WM disclosures: shareholder-director of VU University Medical Center Amsterdam spin-off company Evalua Nederland B.V. and non-executive board-member of Arbo Unie B.V. Both companies operate in the Dutch occupational healthcare market. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

C. S. Kampshoff and J. M. van Dongen shared first authorship.

Contributor Information

C. S. Kampshoff, Email: c.kampshoff@vumc.nl

J. M. van Dongen, Email: j.m.van.dongen@vu.nl

W. van Mechelen, Email: w.vanmechelen@vumc.nl

G. Schep, Email: g.schep@mmc.nl

A. Vreugdenhil, Email: g.vreugdenhil@mmc.nl

J. W. R. Twisk, Email: jwr.twisk@vumc.nl

J. E. Bosmans, Email: j.e.bosmans@vu.nl

J. Brug, Email: j.brug@uva.nl

M. J. M. Chinapaw, Email: m.chinapaw@vumc.nl

Laurien M. Buffart, Phone: +31 (0)20-4449931, Email: l.buffart@vumc.nl

References

- 1.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones LW, Liang Y, Pituskin EN, Battaglini CL, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, Haykowsky M. Effect of exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2011;16(1):112–120. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra SI, Schrerer RW, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O, Gotay CC, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(2):87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roine E, Roine RP, Rasanen P, Vuori I, Sintonen H, Saarto T. Cost-effectiveness of interventions based on physical exercise in the treatment of various diseases: a systematic literature review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(4):427–454. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309990353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mewes JC, Steuten LM, Ijzerman MJ, van Harten WH. Effectiveness of multidimensional cancer survivor rehabilitation and cost-effectiveness of cancer rehabilitation in general: a systematic review. Oncologist. 2012;17(12):1581–1593. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kampshoff CS, Chinapaw MJ, Brug J, Twisk JW, Schep G, Nijziel MR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: results of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study. BMC Med. 2015;13:275. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0513-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kampshoff CS, Buffart LM, Schep G, van Mechelen W, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ. Design of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of exercise interventions after chemotherapy on physical fitness and fatigue. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:658. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Backer I, Schep G, Hoogeveen A, Vreugdenhil G, Kester AD, van Breda E. Exercise testing and training in a cancer rehabilitation program: the advantage of the steep ramp test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(5):610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karvonen J, Vuorimaa T. Heart rate and exercise intensity during sports activities. Practical application. Sports Med. 1988;5(5):303–311. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198805050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinapaw MJ, Buffart LM, van MW, Schep G, Aaronson NK, van Harten WH, et al. Alpe d’HuZes Cancer Rehabilitation (A-CaRe) Research: four randomized controlled exercise trials and economic evaluations in cancer patients and survivors. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19(2):143–156. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balady GJ, Arena R, Sietsema K, Myers J, Coke L, Fletcher GF, Forman D, Franklin B, Guazzi M, Gulati M, Keteyian SJ, Lavie CJ, Macko R, Mancini D, Milani RV, on behalf of the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Clinician’s guide to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(2):191–225. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e52e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohannon RW. Hand-grip dynamometry provides a valid indication of upper extremity strength impairment in home care patients. J Hand Ther. 1998;11(4):258–260. doi: 10.1016/S0894-1130(98)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(2):113–119. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, de Haes JC. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Haes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kind P. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. The EuroQoL instrument: an index of health-related quality of life; pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamers LM, Stalmeier PF, McDonnell J, Krabbe PF, van Busschbach JJ. Measuring the quality of life in economic evaluations: the Dutch EQ-5D tariff. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149(28):1574–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frick KD. Microcosting quantity data collection methods. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S76–S81. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819bc064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakkaart-van RL, Tan S, Bouwmand C. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek. Methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. 2010.

- 24.G-Standaard. In: Z-index. 2014. http://www.z-index.nl/g-standaard/g-standaard. Accessed 3 March 2014.

- 25.Koopmanschap MA, Rutten FF, van Ineveld BM, van RL. The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J Health Econ. 1995;14(2):171–189. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.statline.cbs.nl 2016 [updated 7/7/2016. Available from: http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=83131ned&D1=0,2,4,6&D2=0-1,104,196,243&D3=181,194,207,220,233,246,250–264&HDR=T&STB=G1,G2&VW=T.

- 27.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Leeden R, Leeuw J, Meijer E. Resampling multilevel models. In: Handbook of multilevel analysis. New York: Springer; 2008.

- 29.Black WC. The CE plane: a graphic representation of cost-effectiveness. Med Decis Mak. 1990;10(3):212–214. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9001000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenwick E, O'Brien BJ, Briggs A. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves—facts, fallacies and frequently asked questions. Health Econ. 2004;13(5):405–415. doi: 10.1002/hec.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buffart LM, Kalter J, Chinapaw MJ, Heymans MW, Aaronson NK, Courneya KS, et al. Predicting OptimaL cAncer RehabIlitation and Supportive care (POLARIS): rationale and design for meta-analyses of individual patient data of randomized controlled trials that evaluate the effect of physical activity and psychosocial interventions on health-related quality of life in cancer survivors. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):75. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strasser B, Steindorf K, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM. Impact of resistance training in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(11):2080–2090. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829a3b63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster C, Breckons M, Cotterell P, Barbosa D, Calman L, Corner J, Fenlon D, Foster R, Grimmett C, Richardson A, Smith PW. Cancer survivors’ self-efficacy to self-manage in the year following primary treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(1):11–19. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0384-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrykowski MA, Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB. Magnitude and correlates of response shift in fatigue ratings in women undergoing adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;37(3):341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung ME, Bourne JE, Little JP. Where does HIT fit? An examination of the affective response to high-intensity intervals in comparison to continuous moderate- and continuous vigorous-intensity exercise in the exercise intensity-affect continuum. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalter J, Kampshoff CS, Chinapaw MJ, van MW, Galindo-Garre F, Schep G, et al. Mediators of exercise effects on HRQoL in cancer survivors after chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(10):1859–1865. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craft LL, Vaniterson EH, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW, Courneya KS. Exercise effects on depressive symptoms in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(1):3–19. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aaronson NK, Mattioli V, Minton O, Weis J, Johansen C, Dalton SO, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Stein KD, Alfano CM, Mehnert A, de Boer A, van de Poll-Franse LV. Beyond treatment—psychosocial and behavioural issues in cancer survivorship research and practice. EJC Suppl. 2014;12(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irwin ML, varez-Reeves M, Cadmus L, Mierzejewski E, Mayne ST, Yu H, et al. Exercise improves body fat, lean mass, and bone mass in breast cancer survivors. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(8):1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, Nail LM, Scherer J. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2007;56(1):18–27. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28(6):690–701. doi: 10.1037/a0016136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Squires DA. Explaining high health care spending in the United States: an international comparison of supply, utilization, prices, and quality. International Program in Health Policy and Innovation, The Commonwealth Fund, USA 2012(10):1558–6847. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

At present, raw data of the REACT study forms part of a PhD project, including current data on long-term (cost-)effectiveness. As a consequence, currently, we are unable to publish this dataset. However, the REACT dataset is included in the internationally shared POLARIS database [31], and researchers who are interested to collaborate are invited to prepare a paper proposal.