Abstract

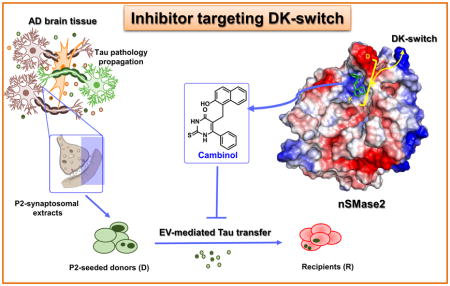

Targeting of molecular pathways involved in the cell-to-cell propagation of pathological tau species is a novel approach for development of disease-modifying therapies that could block tau pathology and attenuate cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. We discovered cambinol through a screening effort and show that it is an inhibitor of cell-to-cell tau propagation. Our in vitro data demonstrates that cambinol inhibits neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase2) enzyme activity in dose response fashion, and suppresses extracellular vesicle (EV) production while reducing tau seed propagation. Our in vivo testing with cambinol shows that it can reduce the nSMase2 activity in the brain after oral administration. Our molecular docking and simulation analysis reveals that cambinol can target the DK-switch in the nSMase2 active site.

Keywords: Tauopathy, nSMase2, extracellular vesicles, cambinol, tau biosensor, molecular modeling

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

A number of tauopathies, including the most prevalent form of dementia – Alzheimer’s disease (AD), have been described, but there are no approved therapies targeting tauopathies that are currently available [1]. The common feature of this group of neurodegenerative disorders is accumulation of tau protein aggregates in neurons and/or glial cells [2]. Notably, propagation of tau starts from a single disease-specific site resulting in the well-defined stereotypic pattern of progression in AD [3], and in other tauopathies, such as argyrophilic grain disease (AGD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), Pick’s disease also known as Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and a subtype of globular glial tauopathies [2, 4]. Onset and severity of clinical symptoms in AD, AGD, FTD and CTE have been shown to correlate with the degree/stage of tau pathology [5–7], making modulation of tau propagation pathways an approach for therapeutic development.

Recent reports suggest a “prion-like” mode of tau propagation [8], including distinct pathological phenotypes induced by disease-specific stable tau strains [9, 10]. Pathological tau oligomers released from affected neurons/glial cells or injected into the brains of mice, can be internalized by healthy cells wherein they act as proteopathic seeds by templating abnormal protein conformations - inducing further spread of pathology, both trans-synaptically [11–14] and through microglia-mediated propagation [15]. The proposed cell-to-cell transfer mechanisms for tau include release/uptake mechanisms [16–18], transfer through tunneling nanotubes [19] and transport in extracellular vesicles (EVs) such as plasma membrane-derived ectosomes and multivesicular body (MVB)-derived exosomes [20–24].

Our screening efforts for tau propagation inhibitors led us to the identification of a brain permeable small molecule – cambinol – that is a known inhibitor of the neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) [25]. In our in vitro model, using HEK293T Tau RD P301S biosensor (tau biosensor) cells [26], cambinol was shown to inhibit the spread of tau oligomers derived from synaptosomes from Alzheimer’s disease patients. Further evaluation of cambinol, as described herein, led to the discovery of a novel binding mode for this inhibitor at the active site of nSMase2, that is a known gatekeeping enzyme involved in ceramide-mediated exosome production [27]. There is significant evidence in the literature on the involvement of nSMase2 in brain exosome biogenesis and exosome-mediated transfer of proteopathic seeds [15, 28–30] through a non-canonical pathway independent of the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT). A noncompetitive inhibitor of this enzyme GW4869 [31, 32], has been previously reported to reduce exosome biogenesis and suppresses pathology propagation in tauopathy mouse models [15]. Mammalian nSMase2 is an integral membrane protein that is highly expressed in the brain, and it is a Mg2+ dependent enzyme with optimum activity at neutral pH [33].

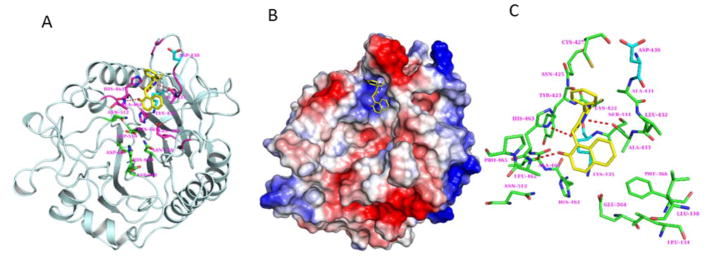

The recently published crystal structure of the active-site domain of the enzyme (pdb: 5UVG) [32] was used in our molecular docking and simulation studies with cambinol which reveals its interaction with the “DK-switch” of the nSMase2. In this enzyme the DK-switch involves the interaction between residues Asp430 (D430) and Lys435 (K435). The enzyme backbone around this region can adopt a loop conformation that directs the Asp residue away from the active site, or an α-helical conformation that directs the Asp residue into the active site to form a salt bridge with the Lys residue [32]. Switching between the loop and helical conformation would reposition the Asp and Lys residues at the active site center and modulate nSMase2 enzymatic activity.

Discovery of this novel molecular mechanism of interaction between cambinol and nSMase2 has implications in the rational design and synthesis of novel nSMase2 inhibitors with superior drug-like properties that could inhibit propagation of pathologic forms of tau.

2. Methods

2.1 nSMase2 enzyme assay

nSMase2 activity was measured in the homogenates of confluent tau biosensor cells or mouse cortex using Amplex red sphingomyelinase assay kit according to manufacturer protocol (ThermoFisher, A12220), using either cell lysate from confluent tau biosensor cells or mouse brain lysate as a source of nSMase2. Detailed protocol in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2 Preparation of human brain derived synaptosomes

Brain autopsy samples were obtained from the University of California Irvine and University of Southern California AD Research Centers. Detailed information about individual cases presented in Supplementary Table S1. Brain tissue was cryopreserved and synaptosomal fractions (P2-fractions, or P2) were prepared as previously described [34]. In order to prepare P2-extracts, aliquots were quickly defrosted at 37°C and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove P2 from sucrose. After aspirating the supernatant, cold PBS was added to each sample in a 1:5 weight/volume ratio. Samples were then sonicated in 10-second intervals three times, incubated on ice for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. P2 extracts were collected and stored at −80°C.

2.3 Functional assays for tau propagation inhibitors

Our functional assays are based on the previously published protocol for flow cytometry detection of tau seeds using HEK293T Tau RD P301S biosensor (tau biosensor) cells [35]. In contrast to the original protocol, two distinct cell populations of tau biosensor cells were employed: donor cells (D), which were seeded with P2-extracts; and recipient cells (R), which never were in direct contact with human brain derived material and could only receive tau seeds from donor cells. Cell viability was assessed with LDH assay (Promega, G1780). The experimental scheme is presented in the Fig. 1A. Detailed protocol is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

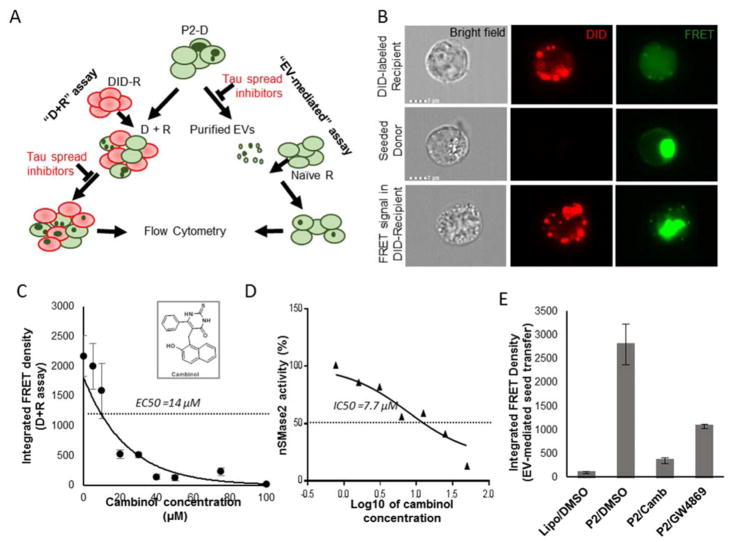

Fig.1. Cambinol inhibits nSMase2 activity in cell extracts and EV-mediated tau seed propagation.

(A) Schematic representation of the “D+R” and EV-mediated assays. P2 - synaptosomal fraction from human AD brain. (B) Imaging flow cytometry: top row - DID-labeled recipient cell, cultured separate from donor cells; middle row - seeded donor cells with FRET-positive tau inclusions; bottom row - DID-labeled recipient cells with FRET-positive tau inclusions after co-culturing with seeded donor cells. (C) Dose-dependent reduction in the tau transfer from donor to recipient cells after treatment with cambinol (D+R assay). (D) Dose-dependent inhibition of nSMase2 activity by cambinol. (E) Treatment of P2-seeded donor cells with cambinol (P2/Camb) or GW4869 (P2/GW4869) at 50μM shows decrease in EV-mediated transfer of tau to recipient cells. Lipo/DMSO group - EVs derived from vehicle treated donor cells treated with empty liposomes and DMSO), P2/DMSO –EVs derived from P2-seeded donor cells treated with DMSO. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.01.

2.4 EV purification and characterization

Donor cells were grown in medium with exosome-depleted FBS (ThermoFisher, A2720803) for 48 hours with or without compounds, cell culture medium was collected and EVs purified using ExoQuick-TC kit (SBI biosciences). For quality control, small amounts of purified EVs were fixed on a copper mesh in glutaraldehyde/paraformaldehyde solution, stained with 2% uranyl acetate solution and imaged on a JEOL 100CX electron microscope at 29,000 times magnification. The remaining samples were either sent for nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) at Alpha Nanotech or used for biochemical characterization. Immunoblot analysis was done by 10–20% Tris-Glycine gel in non-reduced conditions, transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with antibodies against CD63 (ThermoFisher, 10628D), CD9 (ThermoFisher, 10626D), and syntenin-1 (sc-48742), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescent signals were obtained with Super Signal West Femto substrate (Thermo Scientific Pierce 34095) and detected using a BioSpectrum 600 imaging system and quantified using VisionWorks Version 6.6A software (UVP; Upland, CA).

2.5 In vivo treatment with cambinol

Brain permeability and target engagement studies were conducted in C57BL/6J mice. Cambinol stock solution (60mg/ml) was prepared in DMSO. Four hours after oral gavage treatment with cambinol as a single 100 mg/kg dose, or vehicle (2 mice per group), mice were sacrificed and tissue samples (brain and plasma) collected. Drug level evaluation in brain and plasma samples was performed by LC-MS/MS analysis. Brain tissue was homogenized and nSMase2 activity measured as described above.

2.6 Modeling of cambinol binding to nSmase2

Molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation studies were conducted with cambinol using recently published crystal structure of nSmase2 catalytic domain (pdb: 5UVG) [32]. Detailed protocol provided in the Supplementary Materials.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All the data was expressed as the mean ± SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey multiple comparisons test using online web statistical calculator (http://astatsa.com/OneWay_Anova_with_TukeyHSD). Values of *<0.05 and **<0.01 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 Cell-free assay for nSMase2 activity

As previously reported, nSMase2 is upregulated during confluence induced growth arrest [36]. We similarly found that nSMase2 activity was elevated in confluent tau biosensor cells and in confluent SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (data not shown). Cambinol shows dose-dependent inhibition of nSMase2 activity in cell extracts from tau biosensor cells with an IC50 of ~ 7.7μM (Fig. 1D) similar to the previously reported value of 5 μM [25].

3.2 Cambinol inhibits EV-mediated cell-to-cell tau propagation

We show that cambinol inhibits tau seed spread from donor to recipient cells in the “D+R” functional assay. Pooled synaptosomal (P2) extracts from cryopreserved human AD brains (Table S1) were used to seed tau aggregation in donor cells. We found higher levels of seed-competent tau in the synaptosomal extracts, based on the donor cell seeding (Fig.S1). For negative controls, donor cells were transduced with either non-pathological (NL) brain extracts or empty liposomes (Supplementary Fig.S1 A–C). Co-culturing of 1,1’-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD)-labeled recipient cells with P2-seeded donor cells led to the transfer of tau seeds from donor to recipient cells and the appearance of FRET-positive tau inclusions in a small but detectable (~3–5%) population of DiD-labeled recipient cells (Fig.S1 D,E). Of note, donor cells were trypsinized and washed before co-culturing them with recipient cells to avoid their contact with human brain–derived material and liposomes, used for P2 delivery to the donor cells. Only the top 30% of DiD-positive cells, based on signal intensity, were considered recipients (Fig. S1D) to overcome potential DiD cell-to-cell transfer interference [37, 38]. Imaging flow cytometry data confirmed the presence of FRET-positive aggregates in the cells labeled with DiD (Fig.1B). Our data shows that 48-hour treatment with cambinol inhibited the formation of FRET-positive tau aggregates in the recipient cells in a dose-dependent manner with EC50 of 14μM (Fig.1C). Neither P2-seeding nor treatment with nSMase2 inhibitors caused a significant cell death based on the LDH assay (Fig. S2). Further, we purified EVs from donor cell media and evaluated their tau propagation potential. Our data confirmed previously reported EV-mediated transfer of tau seeds from tau biosensor cells to naïve recipient cells [23] and demonstrated that inhibition of nSMase2 in donor cells by either cambinol or GW4869, significantly reduces this selective EV-mediated transfer by 8 and 2.6 times respectively (Fig. 1E).

3.3 Characterization of cell-derived EVs

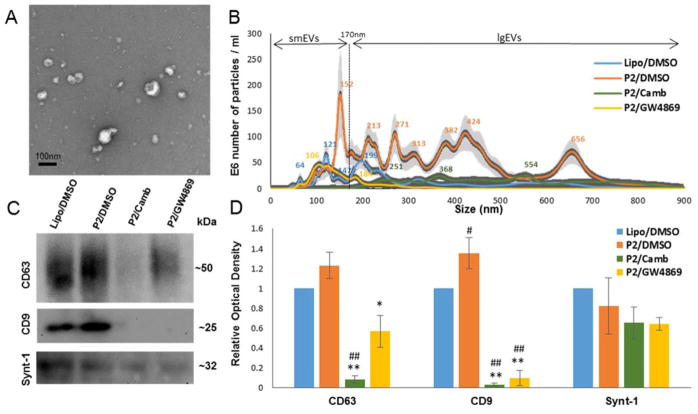

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) were employed to evaluate morphology, size, and number of the extracellular particles released by donor cells. The presence of classic “cup”-shaped vesicles of different sizes in the EV preparations was confirmed by TEM (Fig.2A). NTA revealed 3.5 times more particles released from P2-seeded donors (P2/DMSO sample) compared to non-seeded control cells (Lipo/DMSO sample) (Fig. 2B). Seeding with P2 extracts also led to the shift in the size distribution of smaller particles (<170nm), at size 153nm in P2/DMSO compared to 125 nm in the LIPO/DMSO sample, and the appearance of additional larger particle size range (>170nm). Donor cells which were treated with cambinol (P2/Camb) or GW4869 (P2/GW4869) released less EVs (Fig 2B), as expected. Interestingly, nSMase2 inhibitors not only reduced the number of small “exosome-like” particles but also inhibited the formation of larger particles. The nature of the larger particles is not clear; they could represent populations of ectosomes, or aggregates of smaller EVs [39]. These larger particles are unlikely to be cell fragments, apoptotic bodies, or passively release aggregates, given previously reported low toxicity of AD derived tau strain [9] and the lack of any significant cell toxicity of nSMase2 inhibitors based on the LDH assay. Biochemical characterization of EV fractions for known exosome-enriched markers - CD63, CD9, and syntenin-1, by immunoblot is shown in Fig.2. Levels of CD9, but not CD63 or syntenin-1, was significantly elevated in P2/DMSO samples as compared to the Lipo/DMSO control. Levels of tetraspanins, but not syntenin-1, were significantly decreased in EV samples from nSMase2 inhibitor treatment.

Fig.2. nSMase2 inhibitors suppress release of EVs from P2-seeded tau biosensor cells.

Four groups of samples were analyzed: Lipo/DMSO samples contained EVs released from non-seeded (empty liposome treated) cells after 48 hours of vehicle (DMSO) treatment, P2/DMSO, P2/Camb, and P2/GW4869 - EVs released from P2-seeded tau biosensor cells after 48 hours of treatment wth DMSO, cambinol (50μM) or GW4869 (50μM) treatment respectively. EV samples purified from the same number of donor cells were analyzed per each group. (A) Purified EVs were imaged by transmission electron microscopy. (B) Size distribution of particles in the samples were assessed by nanoparticle tracking analysis. (C) WB analysis for exosome markers, representative images. (D) Densitometry analysis from WB. Histograms represent average relative signal intensity (mean ± SEM) from three independent experiments. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

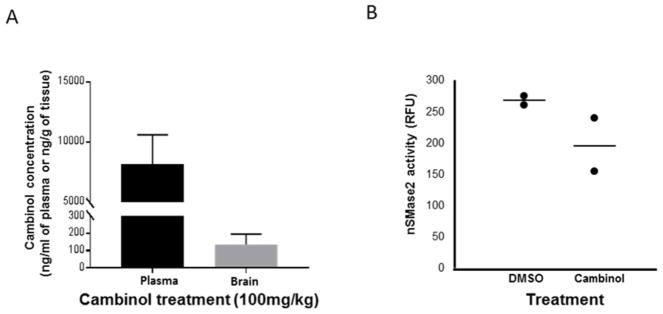

3.4 Brain permeability and target engagement study with cambinol

After oral administration of cambinol (100mg/kg dose) levels of 135.3±60.9 ng/g were detected in the brain at 4h, while levels in plasma was 8150±2450 ng/ml, showing that cambinol has a low brain/plasma ratio (Fig.3A). Furthermore, at 4 hours after cambinol treatment we observe a decrease in nSMase activity in brain homogenates (by ~26.8%) in treated mice compared to controls (Fig.3B), thus indicating potential in vivo target engagement.

Fig.3. Cambinol decreases nSMase2 activity in mouse brain extracts.

C57BL6 mice were treated with 100 mg/kg of cambinol or vehicle (DMSO) by oral gavage and sacrificed 4 hours after the treatment (2 mice per group). (A) Drug concentration in plasma (black column) and brain tissue (grey column) from cambinol treated animals (mean±SEM). (B) nSMase2 activity in the brain homogenates after cambinol- treatment compared to vehicle.

3.5 Modeling of cambinol binding to nSMase2 and interactions

The SwissDock web server [40] was used to predict the cambinol binding to nSMase2. Several potential binding sites were identified but after careful visual inspection, the active site region was selected as preferred binding site for cambinol. The difference in the predicted binding ΔG values between the top ranked site and the active site is marginal (−7.51 vs −7.47 kcal/mol). In the predicted model, cambinol bound to the active site of nSmase2 near the DK-switch (Fig.4) residues Asp430 and Lys435 that are essential for the nSMase2 activity [32]. To further understand the binding interactions between cambinol and nSmase2, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of nSMase2 with cambinol for 50 ns. Notably, cambinol stayed in the nSMase2 binding pocket near the DK-switch throughout the simulation. After 2.5 ns simulation, the sulfur atom from cambinol comes in contact with Lys435 maintaining its contact to this residue throughout the remainder of the simulation. The Asp430 pointed away from the active site during the 50 ns simulation and was not interacting with Lys435. Furthermore, the MMPBSA calculations (Table S2) show that the free energy for cambinol binding to nSMase2 is −14.31 (± 3.23). The free energy value indicates that cambinol binding to nSMase2 at the DK-switch is thermodynamically favorable. Cumulatively, the MD simulation data suggest that cambinol is inhibiting nSMase2 activity by preventing the conformational transition process at the DK-switch region and the interaction between Asp430 and Lys435 at the active site.

Fig.4. Modeling of cambinol binding to nSmase2 catalytic domain.

(A) Model of cambinol binding to DK-switch in the active site domain of nSmase2 catalytic domain. The cambinol (yellow) and the nSmase2 active site residues (green) are shown in stick representation. The DK-switch residues Asp430 and Lys435 are shown in cyan. (B) Molecular surface representation of the nSMAse2 catalytic domain shown with electrostatic potential. The color representations are blue for positive charge, red for negative charge and white for neutral charge. (C) The nSmase2 residues (green) within 5 Å radius surrounding cambinol (yellow). H-bonding between cambinol and nSmase2 are shown in dashed lines (red).

4. Discussion

Elucidation of molecular pathways that are involved in cell-to-cell propagation of pathological tau species could provide novel avenues for therapeutic development to suppress tau pathology propagation and attenuate cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Herein we report on the identification of a screening hit cambinol by employing tau biosensor cells [26, 35]. We show that cambinol a known nSMase2 inhibitor can reduce tau spread from donor cells, seeded with synaptosomal (P2) fractions from AD brain samples, to recipient cells; this inhibition is dose-dependent with an EC50~14μM (Fig.1C). Our studies show that cambinol is more effective than the nSMase2 inhibitor GW4869 in suppressing release of EVs from P2-seeded donor cells (Fig. 2B–D) and EV-mediated transfer of tau seeds from donor to recipient cells (Fig.1E).

Interestingly, P2-seeded tau biosensor cells released 3.5 times more particles compared to cells treated with empty liposomes (Fig. 2B). In our studies, human brain P2 extracts had higher potential to induce propagation compared to synthetic K18 tau seeds in D+R assay (data not shown). This effect could be due to the presence of biological mediators of nSMase2, in the AD brain-derived material, such as amyloid beta [41], tumor necrosis factor alpha [42] or specific tau conformers. Biochemical examination of known exosome markers CD63, CD9 and syntenin-1 [43–45] in the EV fractions by immunoblotting suggests that tau aggregation may interfere with some but not other exosome biogenesis pathways. Specifically, our data suggests that P2-induced tau aggregation may not have a significant effect on the syndecan-syntenin pathway (Fig. 2C, D). An initial in vivo study shows that cambinol can reduce the level of the nSMase2 activity in the brain after oral administration at a dose of 100mg/kg (Fig.3). These data suggest that cambinol can engage the target nSMase2 in the brain and is therefore a promising molecular probe for further evaluation of this mechanism in tauopathy models.

Furthermore, we show for the first time, through molecular docking and simulation studies that inhibition of nSMase2 by cambinol may involve a novel binding mechanism at the active site of nSMase2. Our modeling studies reveal that cambinol can target the DK-switch of nSMase2 (Fig.4 and Table S2), and thus modulate the interaction of catalytic residues D430 and K435 resulting in inhibition of the nSMase2 enzyme activity. In contrast, the cationic GW4869 was reported to bind outside the active site domain interacting with the anionic phosphatidylserine involved in activation of nSMase2 [32].

The physiological level of nSMase2 expression is important for normal brain function [46–48]. The activity of nSMase2 in the brain has been reported to increase with age, which could lead to dysregulation in sphingomyelin turnover [49]. Moreover, brain ceramide levels were found to be elevated in AD compared to age-matched control subjects [50], with a higher order of ceramide/sphingomyelin imbalance in ApoE4 carriers [51]. Thus, elevated nSMase2 activity leading to abnormal exosome release may be an important contributing factor in age-related tau pathology spread. New orally active, brain permeable and efficacious nSMase2 inhibitors are urgently required as preclinical candidates for testing in tauopathy models. The discovery of cambinol and its interactions to the DK-switch of nSMase2 may provide new avenues for targeted design of small molecule inhibitors of this enzyme with advanced drug-like properties.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cambinol inhibits spread of AD synaptosome derived tau seeds, from donor to recipient cells.

Cambinol inhibits nSMase2 through targeting the DK-switch in its active site.

Cambinol inhibits EV-mediated tau propagation.

Cambinol has low brain permeability and inhibition of nSMase activity in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Wayne W. Poon from UC Irvine and Dr. Carol A. Miller from University of Southern California for human autopsy brain samples, UCLA Janis V. Giorgi flow cytometry and Brain Research Institute electron microscopy core facilities, and Professor Gregory Cole for anti-syntenin-1 antibody. Dr. Asa Hatami for advice on the tau propagation assay. This research was made possible by a grant from the UCLA Department of Neurology [VJ] and NIH [R01, KHG].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Orr ME, Sullivan AC, Frost B. A Brief Overview of Tauopathy: Causes, Consequences, and Therapeutic Strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38(7):637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovacs GG. Molecular Pathological Classification of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Turning towards Precision Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms17020189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goedert M, Masuda-Suzukake M, Falcon B. Like prions: the propagation of aggregated tau and alpha-synuclein in neurodegeneration. Brain. 2017;140:266–278. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson PT, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer Disease Neuropathologic Changes With Cognitive Status: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2012;71(5):362–381. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez RD, Grinberg LT. Argyrophilic grain disease: An underestimated tauopathy. Dement Neuropsychol. 2015;9(1):2–8. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642015DN91000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mez J, et al. Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA. 2017;318(4):360–370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mudher A, et al. What is the evidence that tau pathology spreads through prion-like propagation? Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0488-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders DW, et al. Distinct tau prion strains propagate in cells and mice and define different tauopathies. Neuron. 2014;82(6):1271–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narasimhan S, et al. Pathological Tau Strains from Human Brains Recapitulate the Diversity of Tauopathies in Nontransgenic Mouse Brain. J Neurosci. 2017;37(47):11406–11423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1230-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed Z, et al. A novel in vivo model of tau propagation with rapid and progressive neurofibrillary tangle pathology: the pattern of spread is determined by connectivity, not proximity. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(5):667–83. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duyckaerts C, et al. Dissociation of Alzheimer type pathology in a disconnected piece of cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;93(5):501–7. doi: 10.1007/s004010050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu JW, et al. Neuronal activity enhances tau propagation and tau pathology in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(8):1085–92. doi: 10.1038/nn.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokolow S, et al. Pre-synaptic C-terminal truncated tau is released from cortical synapses in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2015;133(3):368–79. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asai H, et al. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18(11):1584–1593. doi: 10.1038/nn.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plouffe V, et al. Hyperphosphorylation and cleavage at D421 enhance tau secretion. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karch CM, Jeng AT, Goate AM. Extracellular Tau levels are influenced by variability in Tau that is associated with tauopathies. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(51):42751–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pooler AM, et al. Physiological release of endogenous tau is stimulated by neuronal activity. EMBO Rep. 2013;14(4):389–94. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tardivel M, et al. Tunneling nanotube (TNT)-mediated neuron-to neuron transfer of pathological Tau protein assemblies. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s40478-016-0386-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dujardin S, et al. Ectosomes: a new mechanism for non-exosomal secretion of tau protein. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon D, et al. Tau overexpression results in its secretion via membrane vesicles. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10(1–4):73–5. doi: 10.1159/000334915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saman S, et al. Exosome-associated tau is secreted in tauopathy models and is selectively phosphorylated in cerebrospinal fluid in early Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):3842–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polanco JC, et al. Extracellular vesicles isolated from brains of rTg4510 mice seed tau aggregation in a threshold-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.709485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, et al. The release and trans-synaptic transmission of Tau via exosomes. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figuera-Losada M, et al. Cambinol, a novel inhibitor of neutral sphingomyelinase 2 shows neuroprotective properties. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0124481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes BB, et al. Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(41):E4376–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411649111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trajkovic K, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319(5867):1244–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dinkins MB, et al. Exosome reduction in vivo is associated with lower amyloid plaque load in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(8):1792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dinkins MB, et al. Neutral Sphingomyelinase-2 Deficiency Ameliorates Alzheimer's Disease Pathology and Improves Cognition in the 5XFAD Mouse. J Neurosci. 2016;36(33):8653–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1429-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo BB, Bellingham SA, Hill AF. The neutral sphingomyelinase pathway regulates packaging of the prion protein into exosomes. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(6):3455–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luberto C, et al. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death in MCF7 by a novel inhibitor of neutral sphingomyelinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(43):41128–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Airola MV, et al. Structure of human nSMase2 reveals an interdomain allosteric activation mechanism for ceramide generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(28):E5549–E5558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705134114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann K, et al. Cloning and characterization of the mammalian brain-specific, Mg2+-dependent neutral sphingomyelinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(11):5895–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gylys KH, Bilousova T. Flow Cytometry Analysis and Quantitative Characterization of Tau in Synaptosomes from Alzheimer's Disease Brains. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1523:273–284. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6598-4_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furman JL, Holmes BB, Diamond MI. Sensitive Detection of Proteopathic Seeding Activity with FRET Flow Cytometry. J Vis Exp. 2015;(106):e53205. doi: 10.3791/53205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchesini N, et al. Role for mammalian neutral sphingomyelinase 2 in confluence-induced growth arrest of MCF7 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(24):25101–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cselenyak A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells rescue cardiomyoblasts from cell death in an in vitro ischemia model via direct cell-to-cell connections. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yumoto K, et al. A novel method for monitoring tumor proliferation in vivo using fluorescent dye DiD. Cytometry A. 2014;85(6):548–55. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu F, et al. The Exosome Total Isolation Chip. ACS Nano. 2017;11(11):10712–10723. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b04878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue):W270–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke CJ, Hannun YA. Neutral sphingomyelinases and nSMase2: bridging the gaps. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758(12):1893–901. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shamseddine AA, Airola MV, Hannun YA. Roles and regulation of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 in cellular and pathological processes. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kowal J, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(8):E968–77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baietti MF, et al. Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(7):677–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roucourt B, et al. Heparanase activates the syndecan-syntenin-ALIX exosome pathway. Cell Res. 2015;25(4):412–28. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wheeler D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced neutral sphingomyelinase-2 modulates synaptic plasticity by controlling the membrane insertion of NMDA receptors. J Neurochem. 2009;109(5):1237–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabatadze N, et al. Inhibition of Neutral Sphingomyelinase-2 Perturbs Brain Sphingolipid Balance and Spatial Memory in Mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2010;88(13):2940–2951. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan LH, et al. Enriched Expression of Neutral Sphingomyelinase 2 in the Striatum is Essential for Regulation of Lipid Raft Content and Motor Coordination. Mol Neurobiol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0784-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babenko NA, Shakhova EG. Long-term food restriction prevents aging-associated sphingolipid turnover dysregulation in the brain. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(3):420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filippov V, et al. Increased ceramide in brains with Alzheimer's and other neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(3):537–47. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandaru VV, et al. ApoE4 disrupts sterol and sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer's but not normal brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(4):591–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.