Abstract

Obesity and diabetes are major challenges to global health, and there is an urgent need for interventions that promote weight loss. Dietary restriction of methionine promotes leanness and improves metabolic health in mice and humans. However, poor long-term adherence to this diet limits its translational potential. In this study, we develop a short-term methionine deprivation (MD) regimen that preferentially reduces fat mass, restoring normal body weight and glycemic control to diet-induced obese mice of both sexes. The benefits of MD do not accrue from calorie restriction, but instead result from increased energy expenditure. MD promotes increased energy expenditure in a sex-specific manner, inducing the fibroblast growth factor (Fgf)-21–uncoupling protein (Ucp)-1 axis only in males. Methionine is an agonist of the protein kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin complex (mTORC)-1, which has been proposed to play a key role in the metabolic response to amino acid–restricted diets. In our study, we used a mouse model of constitutive hepatic mTORC1 activity and demonstrate that suppression of hepatic mTORC1 signaling is not required for the metabolic effects of MD. Our study sheds new light on the mechanisms by which dietary methionine regulates metabolic health and demonstrates the translational potential of MD for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes.—Yu, D., Yang, S. E., Miller, B. R., Wisinski, J. A., Sherman, D. S., Brinkman, J. A., Tomasiewicz, J. L., Cummings, N. E., Kimple, M. E., Cryns, V. L., Lamming, D. W. Short-term methionine deprivation improves metabolic health via sexually dimorphic, mTORC1-independent mechanisms.

Keywords: Fgf21, amino acids, diabetes, obesity, dietary protein

Approximately two-thirds of adults are now overweight or obese in the United States (1), and it is estimated that globally, nearly 2 billion people were overweight in 2014 (2). The increase in obesity has driven a significant increase in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, which now affects over 29 million Americans (12.3% of adults over the age of 20) (1). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity is projected to exceed 70% by 2020. There is therefore great urgency in identifying interventions that promote metabolic health.

Although many individuals who are overweight or obese desire to lose weight, reduced calorie diets have proven notoriously difficult to sustain, in part because of a compensatory slowing of metabolism (2). New and effective strategies to promote a healthy weight are therefore urgently needed. Diet plans based instead on the idea that “a calorie is not just a calorie”—that the macronutrient composition of the diet has calorie-independent effects on metabolic health—have received significant attention because of the possibility of sustainable weight loss while not restricting calories. Vegan diets have received significant attention as a potentially sustainable method to improve metabolic health, and several clinical trials have found that vegan diets promote weight loss, reduce plasmid lipid levels, and improve glycemic control in humans (3–5). However, long-term adherence to a vegan diet is low and similar to a conventional diabetes diet, with only 50% of individuals remaining adherent after 18 mo (6).

A possible mechanism underlying the beneficial metabolic effects of a vegan diet is that plant-based diets have a reduced level of methionine compared to animal sources. Vegans have reduced plasma levels of methionine compared to humans who eat animal proteins (7, 8). Chronic dietary restriction of methionine, typically achieved by placing rodents on diets with an ∼75–80% reduction in methionine and removal of dietary cysteine, extends the lifespan of both mice and rats, and in mice has been shown to promote leanness, insulin sensitivity, and improved lipid metabolism (9–13). Methionine restriction (MR) also prevents the progression of hepatic steatosis in leptin-deficient hyperphagic mice (14), and mice fed low-methionine, high-fat diets gain less weight and are resistant to metabolic dysfunction (15). Although only limited work has been done to examine the effect of restricting other dietary amino acids on metabolic health, recent work has shown that leucine restriction has similar but less pronounced effects than MR on body composition and glucose metabolism, and that MR, but not leucine restriction, reduces hepatic lipid levels and suppresses hepatic lipogenic gene expression (16, 17).

The mechanisms by which MR promotes metabolic health and longevity have been investigated at length but remain poorly understood (18). Many of the metabolic benefits of MR have been attributed to increased levels of the hormone fibroblast growth factor (Fgf)-21, which promotes hepatic insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure. The effects of Fgf21 on hepatic insulin sensitivity are proposed to be mediated by inhibition of the protein kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin complex (mTORC)-1 (19), which may also be inhibited by MR (16). The effects of Fgf21 on energy expenditure are proposed to be mediated by the browning/beiging of white adipose tissue (WAT) (9, 20–23). However, the functional role of mTORC1 inhibition in mediating the effects of MR has not been specifically evaluated.

Clearly, given the continuing increase in metabolically unhealthy individuals, there is a need to identify new approaches to treat or prevent diabetes and obesity. Although short-term methionine-restricted diets have proved feasible in the context of cancer therapy (24, 25), it seems unlikely that long-term adherence to a methionine-restricted diet would be high. In this study, we investigated a short-term intervention, complete methionine deprivation (0% methionine, MD) as a novel way to rapidly and effectively improve metabolic health without reducing calories.

We found that MD rapidly promotes preferential loss of adipose tissue, even when mice continue to consume an unhealthy Western diet (WD), and corrects other metabolic abnormalities including hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance in mice of both sexes. Whereas MD increases energy expenditure in mice of both sexes and robustly induces the Fgf21–uncoupling protein (Ucp)-1 axis in males, energy expenditure in females is increased independently from changes in plasma Fgf21 and WAT Ucp1 expression. Similarly, although Fgf21 has been shown to promote hepatic insulin sensitivity via suppression of mTORC1 signaling, we found that MD promotes hepatic insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance independent of hepatic mTORC1 activity. Our results have revealed previously unrecognized sexually dimorphic effects of dietary methionine on metabolism. In addition, our findings suggest that short-term MD, which may be readily translatable to the clinic through the use of methionine-free medical food already approved for other indications, may be an effective method to rapidly restore metabolic health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and diets

All experiments involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital (Madison, WI, USA). To test the effects of MD in the context of a normal-calorie diet, 9-wk-old female and male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and placed on their respective diets at 14 wk of age. Liver-specific tuberous sclerosis complex-1 (Tsc1) knockout (KO) mice were generated by crossing Albumin-Cre mice from The Jackson Laboratory (003574) with mice expressing a conditional allele of Tsc1 from The Jackson Laboratory (005680); genotyping was performed as described elsewhere (26, 27). For the high-calorie study, mice at 6 wk of age were preconditioned with a 42% high-fat, high-sucrose WD (TD.88137; Envigo, Madison, WI, USA) for 12 wk; control mice were fed Lab Chow Diet 5001 (Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA). Mice were switched to amino acid–defined intervention or control diets at 18 wk of age, as described in Fig. 2A. Amino acid–defined diets were obtained from Envigo. Amino acid–defined diet compositions are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

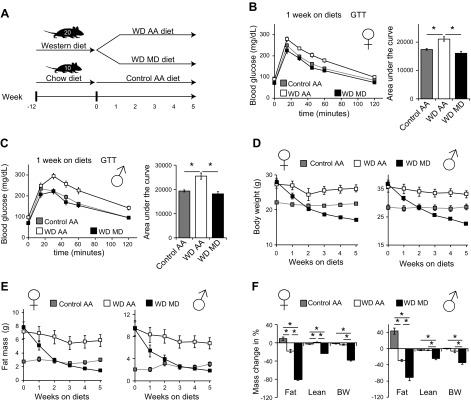

Figure 2.

Dietary MD improves the metabolic health of mice with diet-induced obesity. A) Experimental design of MD as an intervention for diet-induced obesity. B, C) Glucose tolerance tests in female (B) and male (C) mice were conducted after 1 wk on the indicated diets (n = 10 mice/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test, for the area under the curve. D, E) Body weight (D) and fat mass (E) of mice consuming the indicated diets were determined weekly. F) Change in body composition of mice of both sexes after 5 wk on the indicated diets (n = 10 mice/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. Data are means ± sem.

In vivo tests

For glucose, pyruvate, and alanine tolerance tests, food was withheld overnight for 16 h and mice were then injected with glucose (1 g/kg), pyruvate (2 g/kg), or alanine (2 g/kg) intraperitoneally (28, 29). Insulin tolerance tests were performed by withholding food from mice for 4 h, starting at lights on, and then insulin (0.75 U/kg) was injected intraperitoneally. Glucose measurements were taken with a Contour blood glucose meter and test strips (Bayer, Leverkeusen, Germany). We determined mouse body composition with a 3-in-1 Body Composition Analyzer (EchoMRI, Houston, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s procedures. To assay metabolic physiology (O2, CO2, and food consumption) and activity tracking, we acclimated mice to an Oxymax/CLAMS metabolic chamber system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) for ∼24 h before data collection, and data from a continuous 24 h period were then selected for analysis (30). Plasma Fgf21 levels were assayed by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) using plasma collected from mice euthanized after food was withheld overnight for ∼16 h. Triglycerides were measured with a Triglyceride Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) in liver that was harvested and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after food was withheld overnight for ∼16 h. Other tissues for molecular analysis were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed and prepared as described below.

Islet isolation and ex vivo studies

Islets were isolated and an ex vivo glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assay was performed (29, 31). Isolated islets were transferred to a 96-well V-bottom plate and incubated with RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin-streptomycin, and 11.1 mM glucose for 48 h (32). In brief, after a 48 h incubation period, islets were treated with a low-glucose (1.7 mM) Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer preincubation solution for 45 min, followed by a stimulatory high-glucose (16.7 mM) Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer solution for 45 min, as well as by a stimulatory high-glucose (16.7 mM), in combination with 10 nM of exendin-4, a peptide agonist of the glucagon-like peptide receptor, for 45 min. Secretory medium was then saved, and islets were lysed with a lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Insulin secretion and content were analyzed by ELISA (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL, USA).

Histology

Liver was harvested from mice on the various diets. Sections of liver were embedded in OCT, and then cryosectioned and Oil-Red-O stained by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Experimental Pathology Laboratory. For quantification of lipid droplet size in liver, 6 independent fields were obtained for tissue from each mouse by investigators blinded to the treatment group and then quantified using National Institutes of Health (NIH) ImageJ (Bethesda, MD, USA).

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted from liver or adipose tissue with Tri-Reagent (MilliporeSigma, Billerica, MA, USA). The concentration and purity of RNA were determined by absorbance at 260/280 nm, and 1 µg of RNA was used to generate cDNA with Invitrogen Superscript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Oligo dT primers and primers for real-time PCR were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA); primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Reactions were run on Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Invitrogen SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Actin was used to normalize the results from gene-specific reactions.

Immunoblot analysis

Tissue samples from liver and muscle were lysed in cold RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (33), with a FastPrep 24 (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) with bead-beating tubes (13119-500) and ceramic beads (13113-325) from Qiagen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then centrifuged. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Twenty micrograms protein was separated by SDS-PAGE on 8, 10, or 16% resolving gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to PVDF membrane (MilliporeSigma). Antibodies to TSC1, phospho-p70 S6 kinase, p70 S6 kinase, phospho-S6 ribosomal protein, S6 ribosomal protein, phospho-T37/46 4E-BP1, and total 4E-BP1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Imaging was performed on a GE ImageQuant LAS 4000 imaging station (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Quantification was performed by densitometry with ImageJ software.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted with Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Glucose and insulin tolerance tests, as well as other tests involving repeated measurements, were analyzed with 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by the Tukey-Kramer test.

RESULTS

MD promotes glycemic control and reduces adiposity

In light of our goal of identifying an acute, short-term intervention that promotes metabolic health, we elected to study a complete MD (0% methionine) paradigm, rather than the more widely studied regimen of restricting methionine by ∼75–80% (10, 12). Mice raised on laboratory chow were placed on either amino acid–defined control (8.2 g/kg l-methionine) or MD (0 g/kg l-methionine) diets for 5 wk. The full dietary composition of these diets is provided in Supplemental Table 1. In brief, the 2 diets are isocaloric, and both diets contain 3.5 g/kg l-cysteine.

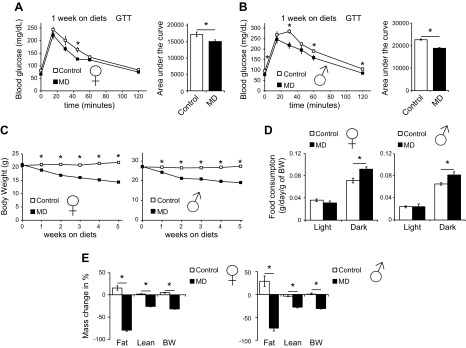

After 1 wk on these diets, we performed a glucose tolerance test. Both female (Fig. 1A) and male (Fig. 1B) mice consuming the MD diet showed a significant improvement in glucose tolerance, and male mice had lower fasting blood glucose. As MR promotes insulin sensitivity in the liver and skeletal muscle (9, 15), we performed insulin and pyruvate tolerance tests over the following 3 wk. We observed a significant improvement in both insulin sensitivity (Supplemental Fig. S1A) and pyruvate tolerance (Supplemental Fig. S1B) in male mice, indicating that MD enhanced both insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Furthermore, the improvement of glucose tolerance is unlikely to be related to increased insulin secretion, as both islet insulin content and ex vivo glucose-stimulated insulin secretion were decreased in mice consuming the MD diet (Supplemental Fig. S1C, D).

Figure 1.

MD improves glucose tolerance and reduces adiposity of both male and female mice. A, B) Glucose tolerance tests in female (A) and male (B) mice fed either control or MD diets for 1 wk. C) Body weight of mice placed on control or MD diets starting at 14 wk of age was tracked weekly for 5 wk. D) Food consumption of mice of both sexes was measured using metabolic chambers after 2 wk on the indicated diets. E) Body composition of mice of both sexes was determined immediately before the diet began and after 5 wk on the indicated diets. Data are represented as means ± sem. Significance for individual time points (A–C) was determined by repeated-measures ANOVA followed by the Tukey test; significance between mice fed control and MD diets was otherwise determined by a Student’s t test (n = 12/group). *P < 0.05.

Male and female mice both exhibited rapid, progressive weight loss in response to MD (Fig. 1C). Because weight loss could result from decreased food intake, we assessed food consumption throughout the course of the experiment and unexpectedly found that MD resulted in increased, not decreased food consumption (Fig. 1D). To determine the source of the weight loss, we compared body composition at baseline to final body composition after 5 wk. Although mice lost both lean and fat mass (Supplemental Fig. S1E), we observed a preferential and profound decrease in adiposity in mice of both sexes (Fig. 1E).

MD normalizes weight and glucose metabolism of mice with diet-induced obesity

To assess whether MD is effective in correcting the metabolic sequelae of obesity, we conducted a 5-wk study of MD in mice that were preconditioned with a commonly used high-fat, high-sugar WD (TD.88137; Envigo) for 12 wk. We then switched the mice to amino acid–defined WDs matching the macronutrient profile of the commercial WD TD.88137 as closely as possible, and with the same fat and carbohydrate sources as TD.88137; these diets contained either 8.2 g/kg methionine (WD AA) or 0 g/kg methionine (WD MD) (Fig. 2A). The full dietary composition of these diets is provided in Supplemental Table 1; but, in brief, the 2 diets are isocaloric and high in fat (from milkfat) and sucrose, and both diets contain 3.5 g/kg l-cysteine. In parallel, chow-fed mice never exposed to a WD were switched to a control amino acid–defined diet.

MD rapidly normalized glucose tolerance in both female and male mice (Fig. 2B, C), despite continued consumption of a high-fat, high-sucrose diet. Although mice on the WD MD diet rapidly lost weight, the improvement in glucose tolerance occurred in advance of weight normalization (Fig. 2D). Mice on a WD MD diet had improved insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and alanine tolerance (Supplemental Fig. S2A–D), suggesting that suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis was enhanced by MD. As with mice on a normal-calorie diet, mice on the MD diet lost weight progressively (Fig. 2D). Mice consuming the WD MD diet lost both lean and fat mass (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Fig. S2E), but we again observed a preferential decrease in adiposity (Fig. 2F). This weight loss was not related to decreased caloric intake in mice of either sex, with female mice consuming the WD MD diet showing a clear increase in caloric consumption compared to mice consuming a WD diet (Fig. 3A).

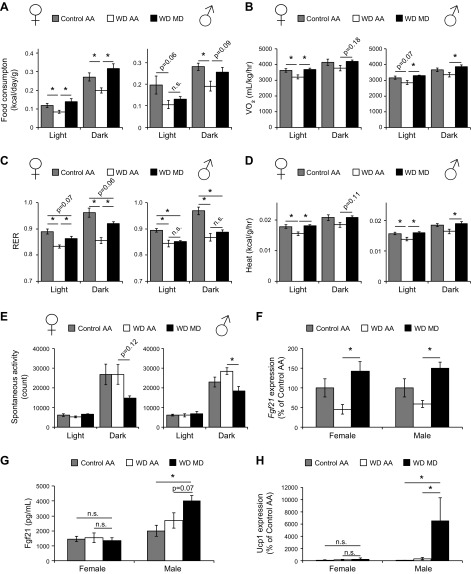

Figure 3.

MD increases energy expenditure and induces the Fgf21-Ucp1 axis in male but not in female mice. A–E) Food consumption (A), oxygen consumption (B), RER (C), heat production (D), and spontaneous activity (E) over a 24 h period were assessed by metabolic chamber after mice were fed the specified diets for 2–3 wk (n = 7–10/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. F) Gene expression of Fgf21 was measured in the livers of mice after food was withheld overnight after 5 wk of feeding specified diets. G) Plasma level of Fgf21 was measured after mice were unfed overnight after 5 wk of consuming the specified diets (n = 6–7/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. H) Gene expression of Ucp1 was measured in the gonadal WAT of mice of both sexes after 5 wk of consuming the specified diets (n = 10/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. When a significant difference was observed in only 1 sex, P ≤ 0.20 or not significant (n.s.) is indicated for the opposite sex. Data are means ± sem.

MD promotes energy expenditure and engages the Fgf21–Ucp1 axis in males

To understand the physiologic basis of weight loss during MD, we examined the impact of MD on energy balance and activity using metabolic chambers. We observed that MD in the context of a WD increased the Vo2 and Vco2 in both female and male mice (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. S3A), but increased the respiratory exchange ratio only in female mice (Fig. 3C). In contrast, MD in the context of a normal-calorie diet increased Vo2 and Vco2 significantly only in male mice, but increased the RER during the dark phase in both male and female mice (Supplemental Fig. S3B–D).

MD also normalized energy expenditure as determined by indirect calorimetry in both female and male mice, with WD MD–fed mice having increased energy expenditure compared to mice on a WD AA diet (Fig. 3D). In the context of a normal-calorie diet, the results differed slightly, with MD increasing energy expenditure only in male mice (Supplemental Fig. S3E). We also observed that MD decreased spontaneous activity in a sex-specific manner, depending on diet, decreasing activity in mice of both sexes (corrected P = 0.12 in females) in the context of a WD, but only in females in the context of a normal-calorie diet (Fig. 3E and Supplemental Fig. S3F).

The metabolic chamber data suggest that the weight loss following MD is most likely due to increased energy expenditure. We determined that Fgf21, a liver-derived hormone that regulates energy balance and is induced by MR (9), is induced at the transcriptional level in mice of both sexes fed a WD MD diet, as compared to mice on a WD AA diet (Fig. 3F). However, whereas the plasma level of Fgf21 was higher in male mice, we observed no increase in Fgf21 in the plasma of female mice consuming the WD MD diet (Fig. 3G).

As Fgf21 promotes energy expenditure and induces uncoupled thermogenesis via upregulating the expression of Ucp1 in WAT (23), we examined the expression of Ucp1 in gonadal WAT of both female and male mice. Consistent with plasma levels of Fgf21, the WD MD diet induced a ∼60-fold increase in Ucp1 expression in male WAT, whereas Ucp1 expression did not increase in female WAT (Fig. 3H). Taken together, these findings suggest that while MD in the context of a WD causes similar metabolic benefits in both sexes, MD may induce increased energy expenditure via different mechanisms in males and females.

MD alters lipid metabolism in liver and adipose tissue

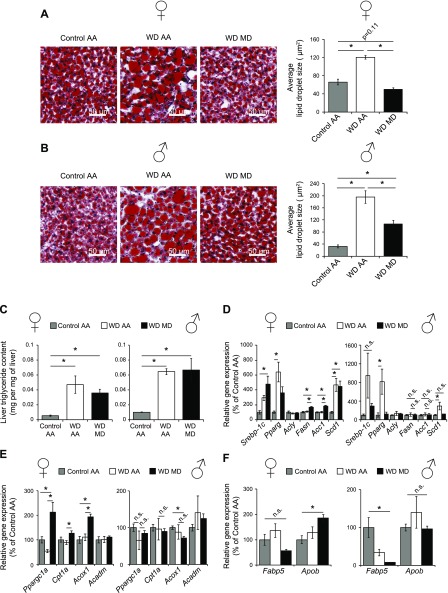

Hepatic lipid accumulation drives many of the negative metabolic effects of diet-induced obesity, including hepatic insulin resistance. There is conflicting information on how dietary protein and methionine affect the accumulation of hepatic lipids, with some studies showing that MR protects against fatty liver disease (14, 15), and other studies showing that a diet deficient in both methionine and choline induces hepatic steatosis (34, 35). We therefore examined hepatic steatosis in MD mice fed a WD. While hepatic steatosis and lipid droplet size increased dramatically in mice fed the WD AA diet, hepatic lipid droplet size decreased dramatically in mice of both sexes (but more strongly in females) after 5 wk of WD MD feeding (Fig. 4A, B). However, while WD-fed mice had dramatically higher levels of triglycerides than mice not exposed to WD, total levels of triglycerides were not significantly reduced in mice fed a WD MD diet (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

MD reduces lipid droplet size, but not triglyceride burden, of mice with diet-induced obesity. A, B) The livers of female (A) and male (B) mice on the indicated diets were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, cryosectioned, and stained with Oil-Red-O. Lipid droplet size was then quantified (n = 4/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. C) Hepatic triglyceride content was quantified (n = 4/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. D–F) The expression of hepatic genes involved in lipid synthesis (D), fatty acid oxidation (E), and lipid transport (F) were determined in the livers of female and male mice after food was withheld overnight. Significance was calculated by ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test (n = 4–6/group). *P < 0.05; when a significant difference was observed in only 1 sex, P ≤ 0.20 or not significant (n.s.) is indicated for the opposite sex. Data are means ± sem.

Long-term MR alters lipid homeostasis in both WAT and the liver (36, 37). Gene expression analysis of key genes regulating hepatic lipid metabolism indicated significant transcriptional remodeling in response to WD MD feeding, particularly in female mice. In particular, the lipogenic genes acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase 1 (Acc1) and fatty acid synthase (Fasn) were upregulated in female mice on the WD MD diet, but we observed no increase in the expression of these genes in male mice (Fig. 4D). Similarly, we observed significant upregulation of genes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation, including peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (Ppargc1a), carnitine palmitoyltransferase (Cpt1a), and acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (Acox1), in female mice fed the WD MD diet, but we observed no change in the expression of these genes in male mice (Fig. 4E). Expression of the genes for apolipoprotein B (Apob), the primary apolipoprotein that exports lipids, and fatty acid binding protein 5 (Fabp5), which is involved in hepatic uptake of free fatty acids, were not significantly altered in mice of either sex fed the WD MD diet vs. WD AA-fed mice. However, expression of Apob was numerically increased in females on the WD MD diet, and mice of both sexes fed the WD MD diet had numerically lower expression of Fabp5 (Fig. 4F). The data suggest that MD alters hepatic lipid metabolism induced by high-fat diet feeding in mice of both sexes, with stronger effects at both the histologic and molecular level in females.

Our observation that white adipose mass is selectively reduced by MD led us to examine lipid metabolism in this tissue as well. Consistent with the sex-specific effects of MR on lipid metabolism in the liver, we observed greater changes in lipogenic gene expression in the WAT of female mice than in male mice, with expression of Fasn trending higher (corrected P = 0.07) in females but not males, and acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase 2 gene (Acc2) expression increased strongly and significantly in females while trending higher in males (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Expression of the lipolytic gene adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl) also increased significantly in females while trending higher in males (corrected P = 0.14) (Supplemental Fig. S4B).

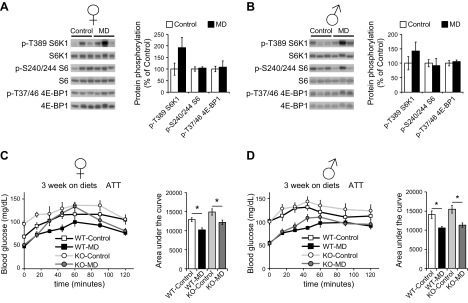

Hepatic mTORC1 is not necessary for the effects of MD

One of the key regulators of the response to amino acids is mTORC1, a protein kinase that is acutely sensitive to amino acids, including methionine (16, 38–40). This sensitivity suggested to us that mTORC1 activity may be decreased in MD mice; further, Fgf21, which was increased in male but not female mice, has been shown to promote hepatic insulin sensitivity by downregulating mTORC1 signaling (19). We therefore examined the effects of MD in the context of both a normal-calorie diet (Fig. 5A, B) or a WD (Supplemental Fig. S5A, B). We observed no significant effect of MD on hepatic mTORC1 signaling in either male or female mice, as determined by phosphorylation of its targets S6K1 and 4E-BP1 or the S6K1 substrate S6 (Fig. 5A, B and Supplemental Fig. S5A, B). However, mTORC1 signaling was decreased by MD in the skeletal muscle of both male and female mice (Supplemental Fig. S5C, D).

Figure 5.

The metabolic effects of MD are independent of hepatic mTORC1 activity. A, B) mTORC1 signaling in the liver of female (A) and male (B) mice fed either control or MD diets for 5 wk was determined by Western blot analysis; quantification was performed with ImageJ (n = 6 mice/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. C, D) Alanine tolerance tests in female (C) and male (D) WT and KO mice fed the indicated diets for 3 wks (n = 5–9/group). *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Sidak’s test comparing control vs. MD of each genotype. Data are means ± sem.

In light of this unexpected finding, we decided to directly test the role of hepatic mTORC1 in the metabolic effects of MD using a mouse model of constitutive hepatic mTORC1 activity. We crossed mice expressing a conditional allele of Tsc1, which encodes an essential negative regulator of mTORC1 activity, with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the albumin promoter (26, 41). Liver-specific Tsc1-KO mice have increased phosphorylation of mTORC1 substrates, compared with wild-type littermates, and MD did not inhibit hepatic mTORC1 signaling in either wild-type or liver-specific Tsc1-KO mice (Supplemental Fig. S6A, B). We conducted glucose and alanine tolerance tests to determine whether MD would improve glycemic control, despite the constitutive activity of hepatic mTORC1. We found that MD improved glucose tolerance in Tsc1-KO mice (Supplemental Fig. S6C) and enhanced suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis equally well in Tsc1-KO mice and their wild-type littermates of both sexes (Fig. 5C, D). Similarly, we observed no effect of hepatic Tsc1 deletion on weight or body composition in response to MD (Supplemental Fig. S6D–G).

Last, as it has previously been shown that hepatic Fgf21 mRNA is induced in liver-specific Tsc1-KO mice (42), we measured the expression of Fgf21 in the livers of both WT and KO mice on either control or MD diets. As expected, we determined that MD increases Fgf21 expression in male wild-type mice, and we observed a similar effect in male Tsc1-KO mice, but MD had no effect on Fgf21 expression in female mice of either genotype (Supplemental Fig. S6H). However, while Tsc1 deletion strongly induced Fgf21 expression in female mice, we observed no effect of Tsc1 deletion on Fgf21 expression in male mice. Thus, the effects of MD on hepatic Fgf21 expression are independent of mTORC1 in both sexes, but Tsc1 deletion upregulates Fgf21 expression independent of diet in females.

DISCUSSION

Dietary MR produces many beneficial effects on metabolic health in both rodents and humans, preventing weight gain and fat accretion, and improving control of blood glucose (10, 18, 43, 44). However, humans have significant difficulties in remaining compliant with severe dietary alterations. In this study, we examined the metabolic impact of complete removal of dietary methionine, which we hypothesized would produce similar but more rapid effects on metabolic health than MR. MD promoted glucose tolerance in both male and female mice consuming a normal-calorie diet and resulted in a profound reduction in adiposity. Further, MD rapidly restored metabolic health in both male and female mice with pre-existing diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance, suggesting that MD may be a useful, short-term intervention for the treatment of pre-existing metabolic syndrome.

MD induced significant weight loss in mice of both sexes. Although mice lost both fat mass and lean mass during MD, there was a striking and preferential decrease in adiposity, as reflected by a loss of nearly 60% of fat mass in 2 wk and 80% of fat mass over the course of the 5 wk experiment. Contrary to the report of Leib and Knight (45) that mice reject diet lacking a single essential amino acid, we observed that the progressive weight loss of MD-fed mice occurred despite increased food consumption. Instead, MD mice lose weight because of increased energy expenditure, likely because of increased metabolic rate, but not because of increased physical activity, as MD mice tend to move less, not more.

Several studies have demonstrated that MR promotes energy expenditure via the beiging or browning of WAT (13, 46). This effect has been linked to increased expression of the energy balance regulating hormone Fgf21, which stimulates the expression of Ucp1 and promotes uncoupled thermogenesis by WAT (9, 23, 47). While MD increased Fgf21 mRNA expression in the livers of both male and female mice, blood levels of Fgf21 were increased only in males. Accordingly, we observed increased expression of Ucp1 in male gonadal WAT, but not in female WAT. This observation suggests that although mice of both sexes fed MD diets have increased energy expenditure, the mechanism linking MR to increased energy expenditure may be independent of Fgf21 and Ucp1, at least in females. Recent work has demonstrated that cold-induced thermogenesis is also mediated by a Fgf21-Ucp1 independent mechanism (48, 49). Further research is needed to specifically identify the biologic basis for the increased energy expenditure induced by MD in both males and females.

Similar to the chronic effects of less severe MR, short-term MD improves glycemic control. Remarkably, only 1 wk of MD is sufficient to fully rescue the glucose tolerance of mice with pre-existing metabolic syndrome. While a reduction in body weight and changes in body composition may contribute to this effect, improved glucose tolerance is observed before weight normalization, suggesting a direct effect of MD on glucose homeostasis. Increased Fgf21 may contribute to this effect—Fgf21 promotes hepatic insulin sensitivity in addition to promoting energy expenditure—but only in males, as females have improved glucose tolerance despite unchanged plasma levels of Fgf21.

As hepatic lipid accumulation plays a causative role in the development of hepatic insulin resistance (50), and MR significantly decreases lipogenic gene expression and increases the expression of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation in the liver (9), we investigated the effect of MD on the expression of these genes and on hepatic lipid deposition. In contrast to MR, MD had minimal effects on the hepatic expression of lipogenic and fatty acid oxidation genes. Despite this, whereas mice consuming WD AA diets showed significantly larger lipid droplet size compared to mice on the control AA diet, the hepatic lipid droplet size was dramatically reduced in mice of both sexes fed the WD MD diet. The reduction in hepatic lipid droplet size is not correlated with a reduction in hepatic triglycerides, as the total triglyceride level was comparable in WD MD– and WD AA–fed mice, suggesting that MD either reduced other types of neutral lipids or that the change in lipid droplet size reflects other alterations in lipid metabolism.

The mTORC1 protein kinase is a key sensor of amino acids including methionine (40). Although mTORC1 signaling is acutely sensitive to amino acid sufficiency in vitro, we found no diminishment in mTORC1 signaling in the livers of mice fed MD diets in vivo. This was surprising not only because methionine is an essential amino acid that stimulates mTORC1 in vitro, but also in light of recent work showing that exogenous Fgf21 promotes hepatic insulin sensitivity via suppression of mTORC1 (19). We therefore tested the role of hepatic mTORC1 in the response to MD using mice with constitutive hepatic mTORC1 activity (Tsc1 liver KO mice). Deleting hepatic Tsc1 had no impact on the metabolic response to MD, suggesting that other signaling pathways likely mediate the effects of MD.

It has been proposed that the metabolic impact of an MR diet is mediated by signaling pathways downstream of increased oxidative stress, as addition of cysteine to an MR diet normalizes hepatic levels of glutathione and reverses the metabolic effects of MR (51). However, this mechanism is unlikely to be the one engaged by the MD diet used in our study, as it is replete with cysteine. Further, recent studies from other laboratories have demonstrated that leucine restriction, which is not involved in glutathione metabolism, has many overlapping metabolic effects with MR (16, 17). These overlapping effects, many of which we have also observed in mice subject to MD, imply that dietary deficiencies in these specific essential amino acids may engage a common molecular mechanism.

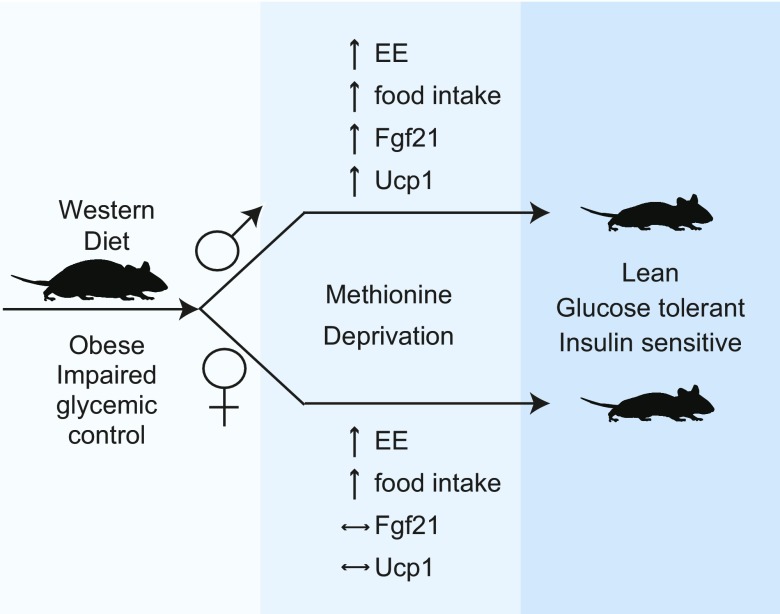

Although we are not the first to examine the metabolic effects of dietary methionine in both male and female mice (52), to our knowledge, our study is the first to show that sex-dependent mechanisms may be involved in mediating the effects of dietary methionine on metabolic health. As outlined in Fig. 6, our results suggest that the Fgf21-Ucp1 axis is engaged by MD only in male mice, and may be dispensable for the metabolic benefits of MD in females as female mice derive these benefits despite unchanged plasma Fgf21 levels and Ucp1 gene expression. Alternatively, MD may promote metabolic health in both sexes through Fgf21-Ucp1–independent mechanisms, as was recently found to be true in the case of cold-induced thermogenesis (48, 49). Our results have also revealed sexually dimorphic effects of MD on hepatic gene expression, particularly with respect to the regulation of lipid metabolism. These molecular differences may highlight the existence of novel, possibly sex-specific drug targets for the treatment of metabolic syndrome.

Figure 6.

Deprivation of dietary methionine improves the metabolic health of both male and female mice, with sexually dimorphic effects on Fgf21 and Ucp1. Specific removal of methionine from the diet improves body composition and glycemic control of diet-induced obese mice of both sexes, but engages the Fgf21-Ucp1 axis only in males.

A cautionary note is that, in the present study, we exclusively analyzed the effects of a short-term MD regimen on the metabolic health of young mice. It remains to be determined whether short-term MD provides similar metabolic benefits to aged animals. This question is important from a translational perspective, as middle-aged and elderly humans are much more likely to be obese or overweight than young ones. It will also be interesting to determine whether the sex-specific effects of MD persist in aged animals, as the levels of sex hormones, which drive many sexually dimorphic phenotypes, diminish with age.

Taken together, our data demonstrates that short-term MD promotes rapid weight loss with a selective reduction in adiposity, restores glucose homeostasis, and corrects other metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity in mice of both sexes. As MR requires relatively long-term adherence to a reduced-methionine diet, short-term MD may be better suited for obesity management. The availability of foods naturally low in methionine as well as methionine-free medical foods (e.g., HCY-2; Mead Johnson Nutrition, Glenview, IL, USA; or Hominex-2; Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH, USA) suggests that interventions based on selectively reducing dietary methionine could move rapidly into the clinic.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Ildiko Kasza and Dr. Caroline Alexander (both from the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, Madison, WI, USA) for assistance in establishing the lipid droplet quantification protocol and advice regarding the collection and analysis of adipose tissue; all members of the D.W.L., M.E.K., and V.L.C. laboratories, and Dr. Dawn Davis, Dr. Matthew Merrins and their laboratories for their assistance and insight [University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison)]; and Dr. Tina Herfel (Envigo, Madison, WI, USA) for assistance with the formulation of the amino acid–defined diets. This research was supported, in part, by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging (NIA) Grants AG041765, AG050135, AG051974, and AG056771 (to D.W.L.); NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant DK102598 (to M.E.K.); a New Investigator Program Award from the Wisconsin Partnership Program (to D.W.L.); a Collaborative Health Sciences Program Award from the Wisconsin Partnership Program (to V.L.C.), the V Foundation for Cancer Research (to V.L.C.); a Glenn Foundation Award for Research in the Biological Mechanisms of Aging (to D.W.L.); and startup funds from the UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health and the UW-Madison Department of Medicine (to V.L.C. and D.W.L.). This research was conducted while D.W.L. was an American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) grant recipient. D.Y. was supported in part by a fellowship from the American Heart Association (17PRE33410983); J.A.W. was supported by a training grant from the NIH/NIDDK (DK007665); N.E.C. was supported by a training grant from the UW Institute on Aging (NIA T32 AG000213). The UW Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) Experimental Pathology Laboratory is supported by UWCCC Support Grant P30 CA014520 from the NIH National Cancer Institute. This work was supported using facilities and resources from the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital. This work does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Apob

apolipoprotein B

- Fabp5

fatty acid binding protein 5

- Fasn

fatty acid synthase

- Fgf

fibroblast growth factor

- KO

knockout

- MD

methionine deprivation

- MR

methionine restriction

- mTORC

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex

- RER

respiratory exchange ratio

- Tsc

tuberous sclerosis complex

- Ucp

uncoupling protein

- WAT

white adipose tissue

- WD

Western diet

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D. Yu, M. E. Kimple, V. L. Cryns, and D. W. Lamming conceived the experiments and secured funding; D. Yu, S. E. Yang, B. R. Miller, J. A. Wisinski, D. S. Sherman, J. A. Brinkman, J. L. Tomasiewicz, and N. E. Cummings performed the experiments; D. Yu, S. E. Yang, B. R. Miller, J. A. Wisinski, J. A. Brinkman, J. L. Tomasiewicz, M. E. Kimple, V. L. Cryns, and D. W. Lamming analyzed the data; and D. Yu, V. L. Cryns, and D. W. Lamming wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2014) National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA, USA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fothergill E., Guo J., Howard L., Kerns J. C., Knuth N. D., Brychta R., Chen K. Y., Skarulis M. C., Walter M., Walter P. J., Hall K. D. (2016) Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring) 24, 1612–1619 10.1002/oby.21538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard N. D., Cohen J., Jenkins D. J., Turner-McGrievy G., Gloede L., Green A., Ferdowsian H. (2009) A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 1588S–1596S 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y. M., Kim S. A., Lee I. K., Kim J. G., Park K. G., Jeong J. Y., Jeon J. H., Shin J. Y., Lee D. H. (2016) Effect of a brown rice based vegan diet and conventional diabetic diet on glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12-week randomized clinical trial. PLoS One 11, e0155918 10.1371/journal.pone.0155918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnard N. D., Cohen J., Jenkins D. J., Turner-McGrievy G., Gloede L., Jaster B., Seidl K., Green A. A., Talpers S. (2006) A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29, 1777–1783 10.2337/dc06-0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnard N. D., Gloede L., Cohen J., Jenkins D. J., Turner-McGrievy G., Green A. A., Ferdowsian H. (2009) A low-fat vegan diet elicits greater macronutrient changes, but is comparable in adherence and acceptability, compared with a more conventional diabetes diet among individuals with type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 109, 263–272 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt J. A., Rinaldi S., Scalbert A., Ferrari P., Achaintre D., Gunter M. J., Appleby P. N., Key T. J., Travis R. C. (2016) Plasma concentrations and intakes of amino acids in male meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans: a cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-Oxford cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 70, 306–312 10.1038/ejcn.2015.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarty M. F., Barroso-Aranda J., Contreras F. (2009) The low-methionine content of vegan diets may make methionine restriction feasible as a life extension strategy. Med. Hypotheses 72, 125–128 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanders D., Forney L. A., Stone K. P., Burk D. H., Pierse A., Gettys T. W. (2017) FGF21 mediates the thermogenic and insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary methionine restriction but not its effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. Diabetes 66, 858–867 10.2337/db16-1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller R. A., Buehner G., Chang Y., Harper J. M., Sigler R., Smith-Wheelock M. (2005) Methionine-deficient diet extends mouse lifespan, slows immune and lens aging, alters glucose, T4, IGF-I and insulin levels, and increases hepatocyte MIF levels and stress resistance. Aging Cell 4, 119–125 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00152.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orentreich N., Matias J. R., DeFelice A., Zimmerman J. A. (1993) Low methionine ingestion by rats extends life span. J. Nutr. 123, 269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lees E. K., Król E., Grant L., Shearer K., Wyse C., Moncur E., Bykowska A. S., Mody N., Gettys T. W., Delibegovic M. (2014) Methionine restriction restores a younger metabolic phenotype in adult mice with alterations in fibroblast growth factor 21. Aging Cell 13, 817–827 10.1111/acel.12238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orgeron M. L., Stone K. P., Wanders D., Cortez C. C., Van N. T., Gettys T. W. (2014) The impact of dietary methionine restriction on biomarkers of metabolic health. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 121, 351–376 10.1016/B978-0-12-800101-1.00011-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malloy V. L., Perrone C. E., Mattocks D. A., Ables G. P., Caliendo N. S., Orentreich D. S., Orentreich N. (2013) Methionine restriction prevents the progression of hepatic steatosis in leptin-deficient obese mice. Metabolism 62, 1651–1661 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ables G. P., Perrone C. E., Orentreich D., Orentreich N. (2012) Methionine-restricted C57BL/6J mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance but have low bone density (published correction in PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104050. PLoS One 7, e51357 10.1371/journal.pone.0051357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lees E. K., Banks R., Cook C., Hill S., Morrice N., Grant L., Mody N., Delibegovic M. (2017) Direct comparison of methionine restriction with leucine restriction on the metabolic health of C57BL/6J mice. Sci. Rep. 7, 9977 10.1038/s41598-017-10381-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanders D., Stone K. P., Dille K., Simon J., Pierse A., Gettys T. W. (2015) Metabolic responses to dietary leucine restriction involve remodeling of adipose tissue and enhanced hepatic insulin signaling. Biofactors 41, 391–402 10.1002/biof.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown-Borg H. M., Buffenstein R. (2017) Cutting back on the essentials: can manipulating intake of specific amino acids modulate health and lifespan? Ageing Res. Rev. 39, 87–95 10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong Q., Hu Z., Zhang F., Cui A., Chen X., Jiang H., Gao J., Chen X., Han Y., Liang Q., Ye D., Shi L., Chin Y. E., Wang Y., Xiao H., Guo F., Liu Y., Zang M., Xu A., Li Y. (2016) Fibroblast growth factor 21 improves hepatic insulin sensitivity by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 in mice. Hepatology 64, 425–438 10.1002/hep.28523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone K. P., Wanders D., Orgeron M., Cortez C. C., Gettys T. W. (2014) Mechanisms of increased in vivo insulin sensitivity by dietary methionine restriction in mice. Diabetes 63, 3721–3733 10.2337/db14-0464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrone C. E., Mattocks D. A., Plummer J. D., Chittur S. V., Mohney R., Vignola K., Orentreich D. S., Orentreich N. (2012) Genomic and metabolic responses to methionine-restricted and methionine-restricted, cysteine-supplemented diets in Fischer 344 rat inguinal adipose tissue, liver and quadriceps muscle. J. Nutrigenet. Nutrigenomics 5, 132–157 10.1159/000339347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douris N., Stevanovic D. M., Fisher F. M., Cisu T. I., Chee M. J., Nguyen N. L., Zarebidaki E., Adams A. C., Kharitonenkov A., Flier J. S., Bartness T. J., Maratos-Flier E. (2015) Central fibroblast growth factor 21 browns white fat via sympathetic action in male mice. Endocrinology 156, 2470–2481 10.1210/en.2014-2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher F. M., Kleiner S., Douris N., Fox E. C., Mepani R. J., Verdeguer F., Wu J., Kharitonenkov A., Flier J. S., Maratos-Flier E., Spiegelman B. M. (2012) FGF21 regulates PGC-1α and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 26, 271–281 10.1101/gad.177857.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durando X., Thivat E., Farges M. C., Cellarier E., D’Incan M., Demidem A., Vasson M. P., Barthomeuf C., Chollet P. (2008) Optimal methionine-free diet duration for nitrourea treatment: a Phase I clinical trial. Nutr. Cancer 60, 23–30 10.1080/01635580701525877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thivat E., Farges M. C., Bacin F., D’Incan M., Mouret-Reynier M. A., Cellarier E., Madelmont J. C., Vasson M. P., Chollet P., Durando X. (2009) Phase II trial of the association of a methionine-free diet with cystemustine therapy in melanoma and glioma. Anticancer Res. 29, 5235–5240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengupta S., Peterson T. R., Laplante M., Oh S., Sabatini D. M. (2010) mTORC1 controls fasting-induced ketogenesis and its modulation by ageing. Nature 468, 1100–1104 10.1038/nature09584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamming D. W., Mihaylova M. M., Katajisto P., Baar E. L., Yilmaz O. H., Hutchins A., Gultekin Y., Gaither R., Sabatini D. M. (2014) Depletion of Rictor, an essential protein component of mTORC2, decreases male lifespan. Aging Cell 13, 911–917 10.1111/acel.12256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arriola Apelo S. I., Neuman J. C., Baar E. L., Syed F. A., Cummings N. E., Brar H. K., Pumper C. P., Kimple M. E., Lamming D. W. (2016) Alternative rapamycin treatment regimens mitigate the impact of rapamycin on glucose homeostasis and the immune system. Aging Cell 15, 28–38 10.1111/acel.12405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontana L., Cummings N. E., Arriola Apelo S. I., Neuman J. C., Kasza I., Schmidt B. A., Cava E., Spelta F., Tosti V., Syed F. A., Baar E. L., Veronese N., Cottrell S. E., Fenske R. J., Bertozzi B., Brar H. K., Pietka T., Bullock A. D., Figenshau R. S., Andriole G. L., Merrins M. J., Alexander C. M., Kimple M. E., Lamming D. W. (2016) Decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids improves metabolic health. Cell Rep. 16, 520–530 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings N. E., Williams E. M., Kasza I., Konon E. N., Schaid M. D., Schmidt B. A., Poudel C., Sherman D. S., Yu D., Arriola Apelo S. I., Cottrell S. E., Geiger G., Barnes M. E., Wisinski J. A., Fenske R. J., Matkowskyj K. A., Kimple M. E., Alexander C. M., Merrins M. J., Lamming D. W. (2017) Restoration of metabolic health by decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids. [E-pub ahead of print] J. Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuman J. C., Truchan N. A., Joseph J. W., Kimple M. E. (2014) A method for mouse pancreatic islet isolation and intracellular cAMP determination. J. Vis. Exp. 88, e50374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truchan N. A., Brar H. K., Gallagher S. J., Neuman J. C., Kimple M. E. (2015) A single-islet microplate assay to measure mouse and human islet insulin secretion. Islets 7, e1076607 10.1080/19382014.2015.1076607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baar E. L., Carbajal K. A., Ong I. M., Lamming D. W. (2016) Sex- and tissue-specific changes in mTOR signaling with age in C57BL/6J mice. Aging Cell 15, 155–166 10.1111/acel.12425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caballero F., Fernández A., Matías N., Martínez L., Fucho R., Elena M., Caballeria J., Morales A., Fernández-Checa J. C., García-Ruiz C. (2010) Specific contribution of methionine and choline in nutritional nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: impact on mitochondrial S-adenosyl-l-methionine and glutathione. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18528–18536 10.1074/jbc.M109.099333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwon D. H., Kang W., Nam Y. S., Lee M. S., Lee I. Y., Kim H. J., Rajasekar P., Lee J. H., Baik M. (2012) Dietary protein restriction induces steatohepatitis and alters leptin/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 signaling in lactating rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 23, 791–799 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasek B. E., Boudreau A., Shin J., Feng D., Hulver M., Van N. T., Laque A., Stewart L. K., Stone K. P., Wanders D., Ghosh S., Pessin J. E., Gettys T. W. (2013) Remodeling the integration of lipid metabolism between liver and adipose tissue by dietary methionine restriction in rats. Diabetes 62, 3362–3372 10.2337/db13-0501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stone K. P., Wanders D., Calderon L. F., Spurgin S. B., Scherer P. E., Gettys T. W. (2015) Compromised responses to dietary methionine restriction in adipose tissue but not liver of ob/ob mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23, 1836–1844 10.1002/oby.21177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goberdhan D. C., Wilson C., Harris A. L. (2016) Amino acid sensing by mTORC1: intracellular transporters mark the spot. Cell Metab. 23, 580–589 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfson R. L., Sabatini D. M. (2017) The dawn of the age of amino acid sensors for the mTORC1 pathway. Cell Metab. 26, 301–309 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu X., Orozco J. M., Saxton R. A., Condon K. J., Liu G. Y., Krawczyk P. A., Scaria S. M., Harper J. W., Gygi S. P., Sabatini D. M. (2017) SAMTOR is an S-adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science 358, 813–818 10.1126/science.aao3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harputlugil E., Hine C., Vargas D., Robertson L., Manning B. D., Mitchell J. R. (2014) The TSC complex is required for the benefits of dietary protein restriction on stress resistance in vivo. Cell Rep. 8, 1160–1170 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornu M., Oppliger W., Albert V., Robitaille A. M., Trapani F., Quagliata L., Fuhrer T., Sauer U., Terracciano L., Hall M. N. (2014) Hepatic mTORC1 controls locomotor activity, body temperature, and lipid metabolism through FGF21. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11592–11599 10.1073/pnas.1412047111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plaisance E. P., Greenway F. L., Boudreau A., Hill K. L., Johnson W. D., Krajcik R. A., Perrone C. E., Orentreich N., Cefalu W. T., Gettys T. W. (2011) Dietary methionine restriction increases fat oxidation in obese adults with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, E836–E840 10.1210/jc.2010-2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cummings N. E., Lamming D. W. (2017) Regulation of metabolic health and aging by nutrient-sensitive signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 455, 13–22 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leib D. E., Knight Z. A. (2015) Re-examination of dietary amino acid sensing reveals a GCN2-independent mechanism. Cell Rep. 13, 1081–1089 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plaisance E. P., Henagan T. M., Echlin H., Boudreau A., Hill K. L., Lenard N. R., Hasek B. E., Orentreich N., Gettys T. W. (2010) Role of beta-adrenergic receptors in the hyperphagic and hypermetabolic responses to dietary methionine restriction. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 299, R740–R750 10.1152/ajpregu.00838.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owen B. M., Ding X., Morgan D. A., Coate K. C., Bookout A. L., Rahmouni K., Kliewer S. A., Mangelsdorf D. J. (2014) FGF21 acts centrally to induce sympathetic nerve activity, energy expenditure, and weight loss. Cell Metab. 20, 670–677 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keipert S., Kutschke M., Ost M., Schwarzmayr T., van Schothorst E. M., Lamp D., Brachthauser L., Hamp I., Mazibuko S. E., Hartwig S., Lehr S., Graf E., Plettenburg O., Neff F., Tschop M. H., Jastroch M. (2017) Long-term cold adaptation does not require FGF21 or UCP1. Cell Metab. 26, 437–446.e435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill C. M., Laeger T., Albarado D. C., McDougal D. H., Berthoud H. R., Münzberg H., Morrison C. D. (2017) Low protein-induced increases in FGF21 drive UCP1-dependent metabolic but not thermoregulatory endpoints. Sci. Rep. 7, 8209 10.1038/s41598-017-07498-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perry R. J., Samuel V. T., Petersen K. F., Shulman G. I. (2014) The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 510, 84–91 10.1038/nature13478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wanders D., Stone K. P., Forney L. A., Cortez C. C., Dille K. N., Simon J., Xu M., Hotard E. C., Nikonorova I. A., Pettit A. P., Anthony T. G., Gettys T. W. (2016) Role of GCN2-independent signaling through a noncanonical PERK/NRF2 pathway in the physiological responses to dietary methionine restriction. Diabetes 65, 1499–1510 10.2337/db15-1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pettit A. P., Jonsson W. O., Bargoud A. R., Mirek E. T., Peelor F. F., III, Wang Y., Gettys T. W., Kimball S. R., Miller B. F., Hamilton K. L., Wek R. C., Anthony T. G. (2017) Dietary methionine restriction regulates liver protein synthesis and gene expression independently of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 phosphorylation in mice. J. Nutr. 147, 1031–1040 10.3945/jn.116.246710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.