Abstract

In this combined experimental (deep ultraviolet resonance Raman (DUVRR) spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM)) and theoretical (molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and stress–strain (SS)) study, the structural and mechanical properties of amyloid beta (Aβ40) fibrils have been investigated. The DUVRR spectroscopy and AFM experiments confirmed the formation of linear, unbranched and β-sheet rich fibrils. The fibrils (Aβ40)n, formed using n monomers, were equilibrated using all-atom MD simulations. The structural properties such as β-sheet character, twist, interstrand distance, and periodicity of these fibrils were found to be in agreement with experimental measurements. Furthermore, Young’s modulus (Y) = 4.2 GPa computed using SS calculations was supported by measured values of 1.79 ± 0.41 and 3.2 ± 0.8 GPa provided by two separate AFM experiments. These results revealed size dependence of structural and material properties of amyloid fibrils and show the utility of such combined experimental and theoretical studies in the design of precisely engineered biomaterials.

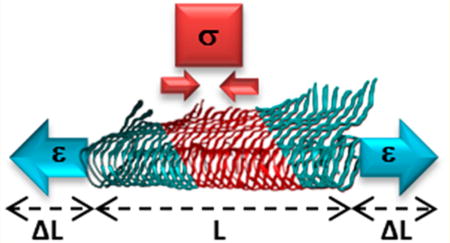

Graphical abstract

Biomaterials encompass various facets of medicine,1 biology,2 chemistry,3,4 and materials science.5 Their applications include scaffolds for cell culture6–10 and catalytic reactions,11–15 devices,16–23 and bioimplants.6,24,25 However, the majority of materials used in these applications consist of classical nonbiological polymeric molecules.26 Biological materials possess lower immunogenic and inflammatory potential than nonbiological polymers27 and, thus, would be better suited for fabrication of artificial body parts and tissue scaffolds in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.28 Additionally, these materials can be used as building blocks for electronic devices and nanowires.29,30

Amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides are promising biomolecules that are capable of forming a variety of materials under diverse conditions.3,4,31–34 Their stability, accurate self-assembly,35 and easy functionalization6 provide an excellent set of material properties that can be exploited for the aforementioned applications.28,36 Driven by intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, and π−π stacking, they can self-assemble molecule by molecule to produce supramolecular architectures (fibrils). This process proceeds through the formation of a natively unfolded intermediate to produce energetically stable, highly ordered, and β-sheet-rich fibrils.37 The fibrils possess characteristic morphologies (hollow cylinders, twisted, and flat ribbons) ~ 100 Å in diameter and have variable lengths up to several micrometers.3,38–42

The fibrils formed by small fragments of Aβ peptides possess high mechanical strength, elasticity, thermochemical stability, and self-healing.4,27,43–45 These properties compare very favorably to most proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous materials.46 They are most likely related to their macromolecular nature and in particular, to the physical and chemical constraints imposed by the individual amino acid residues. However, due to their heterogeneity, high-resolution molecular structures of low molecular weight Aβ amyloid oligomers cannot be easily determined because they are noncrystalline solid materials which are not amenable to X-ray crystallography and liquid state NMR.47–53 Additionally, due to the fast rate of aggregation, structural determination of the early aggregates by using these experimental techniques is extremely difficult. Despite the availability of a sizable amount of data, there are no systematic studies to elucidate the roles of amino acid sequence and structure pertaining to the fundamental material properties such as great strength, sturdiness, and elasticity.

Here we have combined deep ultraviolet resonance Raman (DUVRR) spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) techniques with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and stress–strain (SS) calculations to derive a fundamental understanding of the sequence-structure-material properties relationship of these materials. In particular, structural and mechanical properties such as secondary structure and Young’s modulus (Y) of the Aβ40 fibrils provided by the DUVRR spectroscopy and AFM experiments are compared with the corresponding properties of (Aβ40)n fibrils, for n = 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 120, where n is the number of monomers, derived from MD simulations and SS calculations. These results will elucidate size dependence of structural and mechanical properties of the Aβ40 fibrils and help the development of design rules for the accurate modeling of biomaterials.

Structural Properties of Aβ40 Fibrils

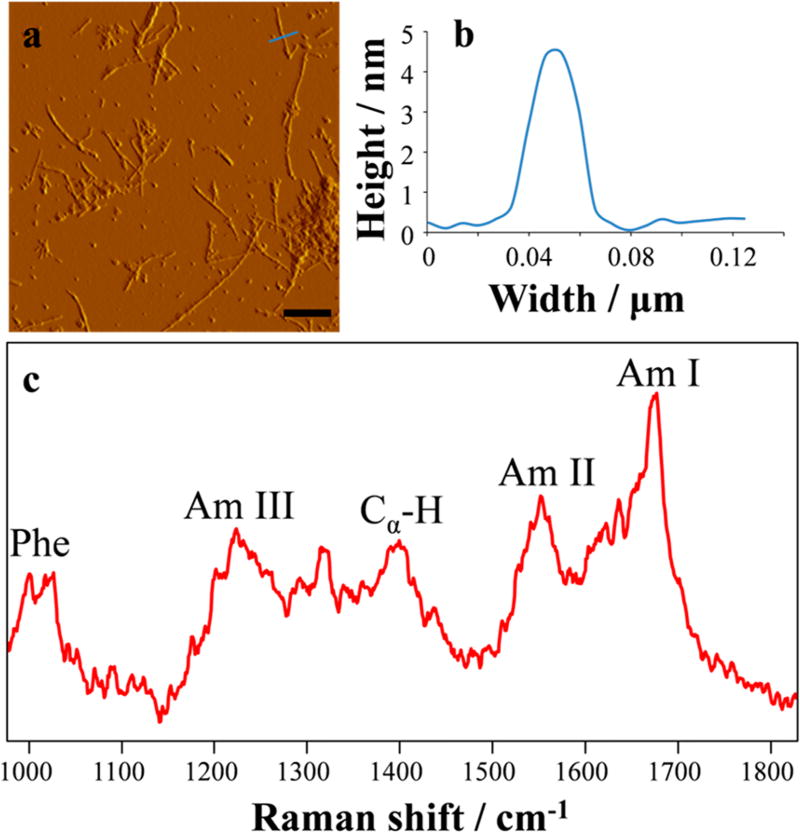

The AFM imaging of Aβ40 fibrils revealed linear, unbranched structures, which are typical for fibrillary aggregates (Figure 1a). The fibril lengths varied from a few hundred nanometers to a few microns, with thickness ranging between 3–5 nm (Figure 1b). The DUVRR spectrum of the Aβ40 fibrils (Figure 1c) was also characteristic of predominant β-sheet peptide conformation.54,55

Figure 1.

AFM image of Aβ40 fibrils (a) and a representative height profile of a fibril (b) corresponding to blue marker. Scale bar: 500 nm. The DUVRR spectrum of Aβ40 fibrils (c) recorded with 199.7 nm excitation.

Specifically, a narrow and intense Amide I peak centered at 1675 cm−1 is indicative of a well-organized cross-β core structure of amyloid fibrils.56 The Amide I vibration consisting mainly of C=O stretching and a small contribution from out-of-phase C–N stretching is known to be sensitive to the peptide’s secondary structure.57 The details of AFM and DUVRR experiments are provided in the Supporting Information (SI).

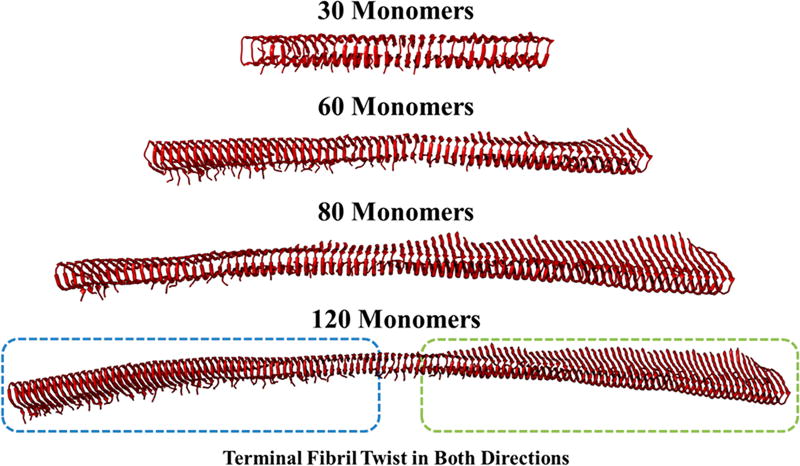

The structures of a wide range of (Aβ40)n fibrils, for n = 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 120 where n is the number of monomers, were equilibrated using all-atom 50–100 ns MD simulations. They were performed using the GROMACS 4.5.6 software58,59 utilizing the GROMOS96 53A6 force field59 in explicit aqueous solution. The details of simulations are provided in the SI. Amyloid fibrils were essentially grown in-silico, starting with a Aβ40 fibril structure that was generously provided by Robert Tycko using a solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) method (PDB ID: 2LMN).37 The root-mean-square-deviations (rmsd) confirmed that the structures were equilibrated during the simulations. The accuracy of the simulated structures was further validated by comparing them with experimental DUVVR and NMR data such as secondary structure analysis, periodicity, and interstrand twist and angle.60 In Aβ40 fibrils, side-chains emanating from the two separate monomer sheets were found to be tightly interdigitated like the teeth of a zipper by intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding, π−π interactions, and CH–π interactions.61 Additionally, there was an absence of water between the β-sheets, therefore this motif has been termed the “dry steric zipper.”61 Steric zippers were formed from self-complementary amino acid sequences, in which their side-chains could mutually interdigitate.61 The fibrils were found to be mostly β-sheet (88.0%) in character with small unordered sections (12.0%) at the beginning of each monomer sequence (Table 1). The formation of the β-sheet rich structures was supported by the measured DUVRR data. The larger fibril (n > 30) structures began to twist in order to gain structural stability and minimize repulsion (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Secondary Structure Analysis of Aβ40 Fibrils Where n = 20 to 120a

| Monomers | β-sheet (%) | Unordered (%) | Fibril Twist (°) | d (nm) | θ (nm) | Periodicity v (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 87.8 | 12.2 | 3.57 ± 1.94 | |||

| 30 | 89.2 | 10.8 | 4.17 ± 2.34 | |||

| 40 | 89.5 | 10.5 | 10.49 ± 5.11 | 0.477 | 1.50 | 114.5 |

| 50 | 90.6 | 9.4 | 8.91 ± 3.63 | 0.479 | 1.47 | 117.3 |

| 60 | 90.4 | 9.6 | 9.19 ± 3.69 | 0.479 | 1.29 | 133.7 |

| 80 | 90.7 | 9.3 | 17.36 ± 4.38 | 0.481 | 1.34 | 129.2 |

| 120 | 90.4 | 9.6 | 25.02 ± 6.05 | 0.481 | 1.32 | 131.2 |

Fibril twist calculated from MD simulations.

This value represents the twist angle from one end of the fibril to the other. d, θ denote the inter-strand distance and twist angles between adjacent monomers, respectively. Length of the fibril, L = n × d, where n is the number of monomer units in an amyloid fibril.

Figure 2.

MD equilibrated structures of (Aβ40)n fibrils with n = 30, 60, 80, and 120.

Smaller fibrils (<20 monomers) produced overall twists less than 1° (Table 1), and therefore have been left out. The larger fibrils possess twists greater than 8°, which further helps to stabilize their secondary structure and allows for reordering to occur before the fibril ruptures beyond repair.

The interstrand distance (d) is defined as the average distance between two adjacent monomer units within the whole fibril. The d value was calculated as a function of length (L = n × d) and all larger fibrils (40–120) produced an average value of 0.480 ± 0.0015 nm. This value is in excellent agreement with previous experimental studies on Aβ40 fibrils (0.47 nm beta-sheet spacing).37 In addition, the interstrand angle (θ) between two adjacent monomer units within the fibril can provide the periodicity of these aggregates through the equation (v = 360 × d/θ). In this equation, periodicity (v) is defined as the minimum length of a fibril to make a complete turn, i.e., the length needed to cover a twist angle of 360°. This minimal length is driven by a balance between mechanical forces dominated by the elasticity (elastic energy penalty) and the electrostatic forces due to the distribution of hydrophobic regions and charges along the backbone.41,62–64 However, amyloid fibril periodicity is tunable as shown by Adamcik et al. by adjusting the salinity or ionic environment such that at high and low salinity, fibrils form relaxed tapes and twist structures, respectively.63 The average computed value of v was 125.2 ± 7.8 nm. This value is also in line with an experimental determined periodicity for amyloidgenic protofibrils such as 3-fold Aβ40 fibrils of 120 ± 20 nm and α-synuclein fibrils of 100–150 nm.41,65 All these results suggested that equilibrated structures of large aggregates (n ~ 100) are realistic models for Aβ40 fibrils that are hundreds of nanometers to micrometers long.66

Mechanical Properties of Aβ40 Fibrils

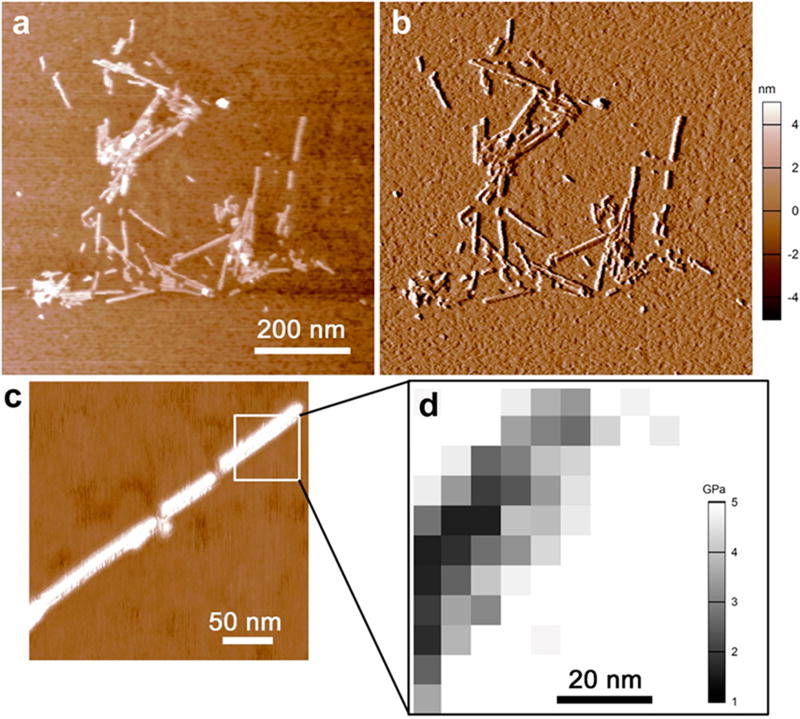

The AFM imaging of the Aβ40 fibrils in air showed the aggregation of fibrils on mica (Figure 3a–c). However, the single fibrils were still evident. The height and width of the single strands were ~4 nm and ~30 nm, respectively (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

AFM imaging of ensemble of Aβ40 fibrils (a) height image and (b) amplitude image. (c) High-resolution image of a single fibril, and (d) inset showing the map of elasticity distribution of a section of a single fibril. The white space in panel (d) represents the stiffer underlying mica surface.

It may be noted that the widths were typically higher than actual width owing to the radius of curvature of the AFM tip. The values of compressive Young’s modulus (Y) were obtained by nanoindentation of the fibrils in both air (dry) and hydrated (buffer) conditions. The indent curves were fitted to the Hertz model that assumes that the strain is elastic and the contact surfaces are frictionless.

The value of Y was 1.79 ± 0.41 GPa, measured for 20 fibrils. This value agrees well with the Y (2–4 GPa) determined for fibrils formed from other peptides such as α-synuclein, lysozyme, and insulin measured using different AFM methods (nanoindentation, peak force quantitative nanomechanical property mapping, and HarmoniX).67,4,46,68,69 AFM imaging of fibrils in PBS buffer showed a similar morphology to the Aβ40 fibril in air. The height of a single fibril in PBS was ~4 nm. This height value is close to the reported 4.6 nm height of the Aβ42 fibril in PBS.70 The value of Y of single fibrils in PBS is 19.68 ± 8.56 MPa (sample size = 20 fibrils). Expectedly, fibrils in a hydrated state are much softer than the fibrils measured in air.71

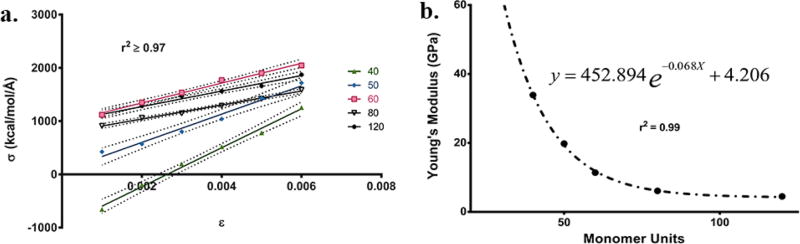

Single strain, SS, force calculations (Figure 4a) allow us to compare the experimental values for Young’s modulus with that from the simulations. We determined the size dependence of Y for all fibrils (Aβ40)n where n = 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 120, by using SS calculations on the structures of fibrils equilibrated through all-atom MD simulations. These calculations were performed using the COMPASSII force field and a protocol implemented in the Materials Studio 7.0 program.72 The details of the SS calculations are provided in SI.

Figure 4.

(a) Stress–Strain (SS) graphs of (Aβ40)40–(Aβ40)120

Single domain structures (one-fold geometry) were chosen for these calculations due to differences in interaction energy contributions to the overall strength of the material and were validated by comparison to experimentally determined geometric parameters. The largest energy contributions come from the hydrogen bonding between monomer units, while the smallest comes from the hydrophobic interactions connecting the two different domains. Furthermore, as Y values are a function of total molecular area, doubling the interaction energy by having two domains, is canceled by doubling the area (Force/Area). Therefore, a one-fold structure will produce the same Y as a 2-fold structure. The small (Aβ40)5–(Aβ40)20 fibrils provided an average modulus value of 45.0 ± 7.5 GPa which is slightly higher, but comparable to the value (13–42 GPa) of small fragments of Aβ peptides reported previously.4 The similarity in computed Y was due to common features of the equilibrated structures of these fibrils. The Aβ fibrils modeled computationally (Aβ405–Aβ40120) were all shorter than the periodicity of their helical pitch and featured significant differences in the pure tensile properties computed.43,73 The (Aβ40)5–(Aβ40)30 structures contained no appreciable fibril twist, which could account for the increase in tensile stiffness observed as no rearrangement or relaxation of structure was possible during SS. Typically for such fibrils, local instabilities can emerge at the ends of the fibrils (on the order of tens of nanometers) that reduce their stability and contribute to their rigidity and disassociation under extreme chemical conditions.43,73 Additionally, for fibrils shorter than their periodicity, bending modes can occur against the cross section with the lowest moment of inertia allowing for increased flexibility as shown by our larger aggregates.62,68 The mechanical properties of the wt-Aβ40 fibrils in implicit solvent using theoretical methods had been computed previously and were found to vary with the length of the fibril and that the long fibrils (20, 40, and 60 monomers in length) were more stable.43,74 The value of Y calculated for (Aβ40)30 (15 nm in length) was half the value of (Aβ40)20 and heralds the next trend seen within the larger fibril structures. It is noteworthy that the computed values for (Aβ40)5–(Aβ40)30 values are significantly higher than the AFM measured value of ~1.8 GPa.

For the larger structures (Aβ40)40–(Aβ40)120, a monoexponential decay between Y and n was observed (Figure 4b) producing a high correlation value of 0.99.

This indicates that a scaling law might exist that could accurately calculate the lowest modulus value for much higher order aggregates. The monoexponential decay fit produced an appreciable plateau value associated with the lowest moduli that can be found for this decay. The value obtained for the plateau was 4.2 GPa (Figure 4b), which pertains to any structure greater than 200 units long. The computed value (4.5 GPa) of Y for the largest fibril (Aβ40)120 should be considered in an excellent agreement with the experimentally measured values of 1.79 ± 0.41 and 3.2 ± 0.8 GPa using two distinct AFM methods (Table 2). It is noteworthy that the experimentally determined Y is compressive or transversal, whereas the calculated Y is purely longitudinal. This could also contribute to the difference in computed and measured values of Y (see SI).75 These results also suggest that the models of fibrils (>100 monomers) approach a more realistic value when compared with traditional AFM stress experiments.

Table 2.

Computed Values of Young’s Modulus (Y) as a Function of Aβ40 Monomers

| monomer units | Young’s modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 38.0 |

| 6 | 36.2 |

| 7 | 37.3 |

| 8 | 54.1 |

| 9 | 44.5 |

| 10 | 51.2 |

| 20 | 54.3 |

| 30 | 26.0 |

| 40 | 33.9 |

| 50 | 19.8 |

| 60 | 11.4 |

| 80 | 6.1 |

| 120 | 4.5 |

In this study, we have combined complementary experimental (DUVRR and AFM) and theoretical (MD simulations and SS calculations) techniques to investigate the structural and mechanical properties of Aβ40 fibrils. The AFM experiments showed the formation of linear and unbranched Aβ40 fibrils with varying length (a few hundred nanometers to a few microns) and thickness (3–5 nm). The DUVRR spectrum provided a high relative intensity of the Amide I peak at 1675 cm−1 that was characteristic of β-sheet rich fibrils. The MD equilibrated fibrils formed using 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 120 monomers were also dominated by β-sheets (88.0%) and formed through a zipper created by self-complementary amino acid residues. The other structural properties (twist, interstrand distance and periodicity) of these fibrils were also in agreement with experimental measurements. The AFM experiments provided the values of compressive Y of 1.79 ± 0.41 GPa (sample size = 20 fibrils) in air (dry) condition. The SS calculations on the small equilibrated (Aβ40)5–(Aβ40)20 fibrils provided an average Y value of 45.0 ± 7.5 GPa that was significantly higher than the measured value. However, the larger structures (Aβ40)40–(Aβ40)120, exhibited a monoexponential decay and produced a high correlation value of 0.99, which suggested the existence of a scaling law. The monoexponential decay using this law provided Y = 4.206 GPa that can be associated with any structure greater than 200 units long. This value is in excellent agreement with AFM nanoindention experimental value of 1.8 ± 0.41 GPa. The results reported in this study will advance our efforts to understand sequence-structure-material properties relationship of biomaterials and to develop “design rules” for their computational modeling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. CHE-1152752 (I.K.L.). Financial support from the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program of the Florida State Health Department (DOH grant number 08KN-11) to R.P. is gratefully acknowledged. Computational resources from the Center for Computational Science at the University of Miami are greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

- Complete references for refs 6, 25, 50, and 53 from the main text as well as further details on experimental and computational procedures pertaining to preparation of Aβ40 fibrils samples, deep ultraviolet resonance Raman (DUVRR) spectroscopy, AFM imaging, nanoindentation approach, computational modeling, molecular dynamics simulations, geometrical parameters, and stress–strain calculations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Ratner BD, Hoffman AS, Schoen FJ, Lemons JE. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. 2. Elsevier Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2004. p. 824. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badylak SF, Dziki JL, Sicari BM, Ambrosio F, Boninger ML. Mechanisms by Which Acellular Biologic Scaffolds Promote Functional Skeletal Muscle Restoration. Biomaterials. 2016;103:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JF, Knowles TPJ, Dobson CM, Macphee CE, Welland ME. Characterization of the Nanoscale Properties of Individual Amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:15806–15811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604035103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowles TP, Fitzpatrick AW, Meehan S, Mott HR, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Welland ME. Role of Intermolecular Forces in Defining Material Properties of Protein Nanofibrils. Science. 2007;318:1900–1903. doi: 10.1126/science.1150057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z, Tang Y, Fang H, Su Z, Xu B, Lin Y, Zhang P, Wei X. Decellularized Scaffolds Containing Hyaluronic Acid and EGF for Promoting the Recovery of Skin Wounds. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 2015;26:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob RS, et al. Self Healing Hydrogels Composed of Amyloid Nano Fibrils for Cell Culture and Stem Cell Differentiation. Biomaterials. 2015;54:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mankar S, Anoop A, Sen S, Maji SK. Nanomaterials: Amyloids Reflect Their Brighter Side. Nano Rev. 2011;2:6032. doi: 10.3402/nano.v2i0.6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steins A, Dik P, Müller WH, Vervoort SJ, Reimers K, Kuhbier JW, Vogt PM, van Apeldoorn AA, Coffer PJ, Schepers K. In Vitro Evaluation of Spider Silk Meshes as a Potential Biomaterial for Bladder Reconstruction. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussein KH, Park K-M, Kang K-S, Woo H-M. Biocompatibility Evaluation of Tissue-engineered Decellularized Scaffolds for Biomedical Application. Mater. Sci. Eng., C. 2016;67:766–778. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su WW, Han Z. Self-Assembled Synthetic Protein Scaffolds: Biosynthesis and Applications. ECS Trans. 2013;50:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seal M, Ghosh C, Basu O, Dey SG. Cytochrome c Peroxidase Activity of Heme Bound Amyloid β Peptides. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirats A, Alí-Torres J, Rodríguez-Santiago L, Sodupe M. Stability of Transient Cu+Aβ (1–16) Species and Influence of Coordination and Peptide Configuration on Superoxide Formation. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2016;135:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedmann MP, Torbeev V, Zelenay V, Sobol A, Greenwald J, Riek R. Towards Prebiotic Catalytic Amyloids Using High Throughput Screening. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolisetty S, Arcari M, Adamcik J, Mezzenga R. Hybrid Amyloid Membranes for Continuous Flow Catalysis. Langmuir. 2015;31:13867–13873. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rufo CM, Moroz YS, Moroz OV, Stöhr J, Smith TA, Hu X, DeGrado WF, Korendovych IV. Short Peptides Self-assemble to Produce Catalytic Amyloids. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:303–309. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teo AJT, Mishra A, Park I, Kim Y-J, Park W-T, Yoon Y-J. Polymeric Biomaterials for Medical Implants and Devices. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016;2:454–472. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Huang Y, Yu Y, Li G, Karamanos Y. Self-Catalyzed Assembly of Peptide Scaffolded Nanozyme as a Dynamic Biosensing System. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:2833–2839. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b11567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Li Y, Zhong C. Amyloid-directed Assembly of Nanostructures and Functional Devices for Bionanoelectronics. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:4953–4958. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00374a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, Bolisetty S, Mezzenga R. Hybrid Nanocomposites of Gold Single-Crystal Platelets and Amyloid Fibrils with Tunable Fluorescence, Conductivity, and Sensing Properties. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:3694–3700. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasso L, Suei S, Domigan L, Healy J, Nock V, Williams MAK, Gerrard JA. Versatile Multi-functionalization of Protein Nanofibrils for Biosensor Applications. Nanoscale. 2014;6:1629–1634. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05752f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Adamcik J, Mezzenga R. Biodegradable Nanocomposites of Amyloid Fibrils and Graphene with Shape-memory and Enzyme-sensing Properties. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Zhao X, Li J, Kuang X, Fan Y, Wei G, Su Z. Electrostatic Assembly of Peptide Nanofiber–Biomimetic Silver Nanowires onto Graphene for Electrochemical Sensors. ACS Macro Lett. 2014;3:529–533. doi: 10.1021/mz500213w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser CAE, Maurer-Stroh S, Martins IC. Amyloid-based Nanosensors and Nanodevices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:5326–5345. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00082j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trimaille T, Pertici V, Gigmes D. Recent Advances in Synthetic Polymer Based Hydrogels for Spinal Cord Repair. C. R. Chim. 2016;19:157–166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peralta MDR, et al. Engineering Amyloid Fibrils from β-Solenoid Proteins for Biomaterials Applications. ACS Nano. 2015;9:449–463. doi: 10.1021/nn5056089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irimia-Vladu M. ″Green″ Electronics: Biodegradable and Biocompatible Materials and Devices for Sustainable Future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:588–610. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60235d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cherny I, Gazit E. Amyloids: Not Only Pathological Agents but also Ordered Nanomaterials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4062–4069. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheibel T, Parthasarathy R, Sawicki G, Lin XM, Jaeger H, Lindquist SL. Conducting Nanowires Built by Controlled Self-assembly of Amyloid Fibers and Selective Metal Deposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:4527–4532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0431081100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu K, Jacob J, Thiyagarajan P, Conticello VP, Lynn DG. Exploiting Amyloid Fibril Lamination for Nanotube Self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6391–6393. doi: 10.1021/ja0341642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reches M, Gazit E. Casting Metal Nanowires Within Discrete Self-assembled Peptide Nanotubes. Science. 2003;300:625–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1082387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S. Fabrication of Novel Biomaterials Through Molecular Self-assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1171–1178. doi: 10.1038/nbt874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meersman F, Dobson CM. Probing the Pressure–Temperature Stability of Amyloid Fibrils Provides New Insights into Their Molecular Properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2006;1764:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamada D, Yanagihara I, Tsumoto K. Engineering Amyloidogenicity Towards the Development of Nanofibrillar Materials. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez de la Paz M, Goldie K, Zurdo J, Lacroix E, Dobson CM, Hoenger A, Serrano L. De Novo Designed Peptide-based Amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16052–16057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252340199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang SG, Holmes T, Lockshin C, Rich A. Spontaneous Assembly of a Self-Complementary Oligopeptide to Form a Stable Macroscopic Membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:3334–3338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gelain F, Bottai D, Vescovi A, Zhang S. Designer Self-assembling Peptide Nanofiber Scaffolds for Adult Mouse Neural Stem Cell 3-dimensional Cultures. PLoS One. 2006;1:e119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin NO, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. A Structural Model for Alzheimer’s b-amyloid Fibrils Based on Experimental Constrains from Solid State NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiraham T, Cohen AS. Reconstitution of Amyloid Fibrils from Alkaline Extracts. J. Cell Biol. 1967;35:459–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.35.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielsen L, Frokjaer S, Carpenter JF, Brange J. Studies of the Structure of Insulin Fibrils by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy and Electron Microscopy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001;90:29–37. doi: 10.1002/1520-6017(200101)90:1<29::aid-jps4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jimenez JL, Nettleton EJ, Bouchard M, Robinson CV, Dobson CM, Saibil HR. The Protofilament Structure of Insulin Amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142459399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khurana R, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Pope M, Li J, Nielson L, Ramirez-Alvarado M, Regan L, Fink AL, Carter SA. A General Model for Amyloid Fibril Assembly Based on Morphological Studies Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2003;85:1135–44. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serpell LC, Sunde M, Benson MD, Tennent GA, Pepys MB, Fraser PE. The Protofilament Substructure of Amyloid Fibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:1033–1039. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Z, Paparcone R, Buehler MJ. Alzheimer’s Aβ(1–40) Amyloid Fibrils Feature Size-Dependent Mechanical Properties. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2053–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paparcone R, Pires MA, Buehler MJ. Mutations Alter the Geometry and Mechanical Properties of Alzheimer’s A beta(1–40) Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8967–8977. doi: 10.1021/bi100953t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lv S, Dudek DM, Cao Y, Balamurali MM, Gosline J, Li H. Designed Biomaterials to Mimic the Mechanical Properties of Muscles. Nature. 2010;465:69–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knowles TPJ, Buehler MJ. Nanomechanics of Functional and Pathological Amyloid Materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:469–479. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petkova AT, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Experimental Constraints on Quaternary Structure in Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riek R, Guntert P, Dobeli H, Wipf B, Wuthrich K. NMR Studies in Aqueous Solution Fail to Identify Significant Conformational Differences Between the Monomeric Forms of Two Alzheimer Peptides with Widely Different Plaque-competence, Ab(1–40)ox and Ab(1–42)ox. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:5930–5936. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sipe JD, Cohen A. S Review: History of the Amyloid Fibril. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:88–98. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernstein SL, et al. Amyloid-β protein Oligomerization and the Importance of Tetramers and Dodecamers in the Aetiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nchem.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Baumketner A, Shea J-E, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT. Amyloid β-Protein: Monomer Structure and Early Aggregation States of Aβ42 and Its Pro19 Alloform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2075–2084. doi: 10.1021/ja044531p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamley IW. The Amyloid Beta Peptide: A Chemist’s Perspective. Role in Alzheimer’s and Fibrillization. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:5147–5192. doi: 10.1021/cr3000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nasica-Labouze J, et al. Amyloid β Protein and Alzheimer’s Disease: When Computer Simulations Complement Experimental Studies. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:3518–3563. doi: 10.1021/cr500638n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oladepo SA, Xiong K, Hong Z, Asher SA, Handen J, Lednev IK. UV Resonance Raman Investigations of Peptide and Protein Structure and Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2604–2628. doi: 10.1021/cr200198a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Popova LA, Kodali R, Wetzel R, Lednev IK. Structural Variations in the Cross-beta Core of Amyloid Beta Fibrils Revealed by Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6324–6328. doi: 10.1021/ja909074j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shashilov VA, Sikirzhytski V, Popova LA, Lednev IK. Quantitative Methods for Structural Characterization of Proteins Based on Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Methods. 2010;52:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lednev IK. Vibrational Spectroscopy: Biological Applications of Ultraviolet Raman Spectroscopy. In: Uversky VN, Permyakov EA, editors. Protein Structures, Methods in Protein Structures and Stability Analysis. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindahl E, Hess B, van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: A Package for Molecular Simulation and Trajectory Analysis. J. Mol. Model. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE, Van Gunsteren WF. A Biomolecular Force Field Based on the Free Enthalpy of Hydration and Solvation: The GROMOS Force-field Parameter Sets 53A5 and 53A6. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1656–1676. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bertini I, Gonnelli L, Luchinat C, Mao J, Nesi A. A New Structural Model of Aβ40 Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16013–16022. doi: 10.1021/ja2035859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eisenberg D, Jucker M. The Amyloid State of Proteins in Human Diseases. Cell. 2012;148:1188–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adamcik J, Jung J-M, Flakowski J, De Los Rios P, Dietler G, Mezzenga R. Understanding Amyloid Aggregation by Statistical Analysis of Atomic Force Microscopy Images. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:423–428. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adamcik J, Mezzenga R. Adjustable Twisting Periodic Pitch of Amyloid Fibrils. Soft Matter. 2011;7:5437–5443. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Assenza S, Adamcik J, Mezzenga R, De Los Rios P. Universal Behavior in the Mesoscale Properties of Amyloid Fibrils. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113:268103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.268103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Molecular Structural Basis for Polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:18349–18354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paparcone R, Sanchez J, Buehler MJ. Comparative Study of Polymorphous Alzheimer’s A beta(1–40) Amyloid Nanofibrils and Microfibers. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2010;7:1279–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sweers K, van der Werf K, Bennink M, Subramaniam V. Nanomechanical Properties of Alpha-synuclein Amyloid Fibrils: A Comparative Study by Nanoindentation, Harmonic Force Microscopy, and Peakforce QNM. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011;6:270. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adamcik J, Lara C, Usov I, Jeong JS, Ruggeri FS, Dietler G, Lashuel HA, Hamley IW, Mezzenga R. Measurement of Intrinsic Properties of Amyloid Fibrils by the Peak Force QNM Method. Nanoscale. 2012;4:4426–4429. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30768e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sweers KKM, Bennink ML, Subramaniam V. Nanomechanical Properties of Single Amyloid Fibrils. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2012;24:243101. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/24/24/243101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lv ZJ, Condron MM, Teplow DB, Lyubchenko YL. Nanoprobing of the Effect of Cu2+ Cations on Misfolding, Interaction and Aggregation of Amyloid beta Peptide. J. Neuroimmune Pharm. 2013;8:262–273. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9416-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grant CA, Brockwell DJ, Radford SE, Thomson NH. Effects of Hydration on the Mechanical Response of Individual Collagen Fibrils. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;92:233902–233904. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Accelrys. Materials Studio Accelrys 7.0. :2001–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi B, Yoon G, Lee SW, Eom K. Mechanical Deformation Mechanisms and Properties of Amyloid Fibrils. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:1379–1389. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03804e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paparcone R, Buehler MJ. Failure of Abeta(1–40) Amyloid Fibrils Under Tensile Loading. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3367–3374. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adamcik J, Berquand A, Mezzenga R. Single-step Direct Measurement of Amyloid Fibrils Stiffness by Peak Force Quantitative Nanomechanical Atomic Force Microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;98:193701-1–193701-3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.