Abstract

Schneiderian papillomas (ISP) of the middle ear are uncommon conditions, with only 45 cases published within literature. They are locally aggressive tumours, with a high rate of recurrence and associated malignancy. We present a rare case of a 53-year-old man presenting with unilateral pulsatile tinnitus, otorrhoea, aural fullness, pruritis and hearing loss. Angiography was employed to exclude a glomus tumour and the patient underwent a modified radical mastoidectomy. Tissue samples confirmed a histological diagnosis of ISP of the middle ear. Follow-up magnetic resonanc imaging one year postoperatively showed no evidence of disease recurrence.

Keywords: Nasal mucosa, Papilloma, Inverted, Middle ear

Introduction

Schneiderian or inverted papillomas (ISP) arising from the middle ear are a rare entity with only 45 reported cases in the literature. Patients present most commonly with hearing loss, otalgia, otorrhoea, aural fullness and, to a lesser extent, facial nerve paralysis, tinnitus and headaches.1 These are locally aggressive tumours, which can erode through middle ear structures and invade the mastoid, temporal bone and skull base to cause significant morbidity to cranial nerves, large vessels and middle and posterior cranial fossae contents.1,2 Malignant transformation has been reported as occurring in 35.3–77% of cases.3,4 Recurrence rates are high at 32% and depend on the extent of surgical resection of disease.5

Case history

We present a rare case of a 53-year-old man who initially presented to our emergency ear, nose and throat clinic with a five-year history of right-sided hearing loss, pulsatile tinnitus, recurrent otorrhoea, aural fullness and pruritus. After a poor response to oral and topical antibiotics, he was referred for a consultant opinion to investigate the pulsatile tinnitus and hearing loss. On further assessment, he was found to have an atypical, pulsatile aural polyp emanating from the right middle ear, but not involving the tympanic membrane. Audiometric studies demonstrated a right sided conductive hearing loss of 40 dB. Owing to the suspicious nature of the lesion, further imaging was undertaken to elicit a diagnosis. While awaiting radiological investigations, the patient developed a right sided House-Brackmann grade 4 lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy.

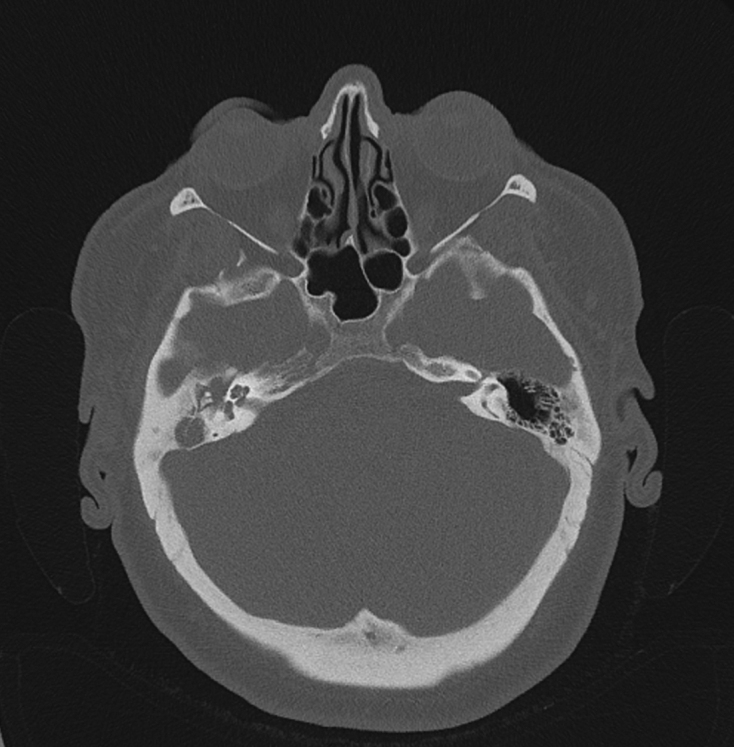

Comptued tomography (CT) of the temporal bones showed complete opacification of the aditus ad antrum, middle ear cavity and Eustachian tube (Fig 1). Ossicular continuity was maintained with minor erosions of malleus and incus. No erosion of the otic capsule or jugular notch was noted.

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomography of the temporal bones showing opacification of the right middle ear cavity by a soft tissue mass

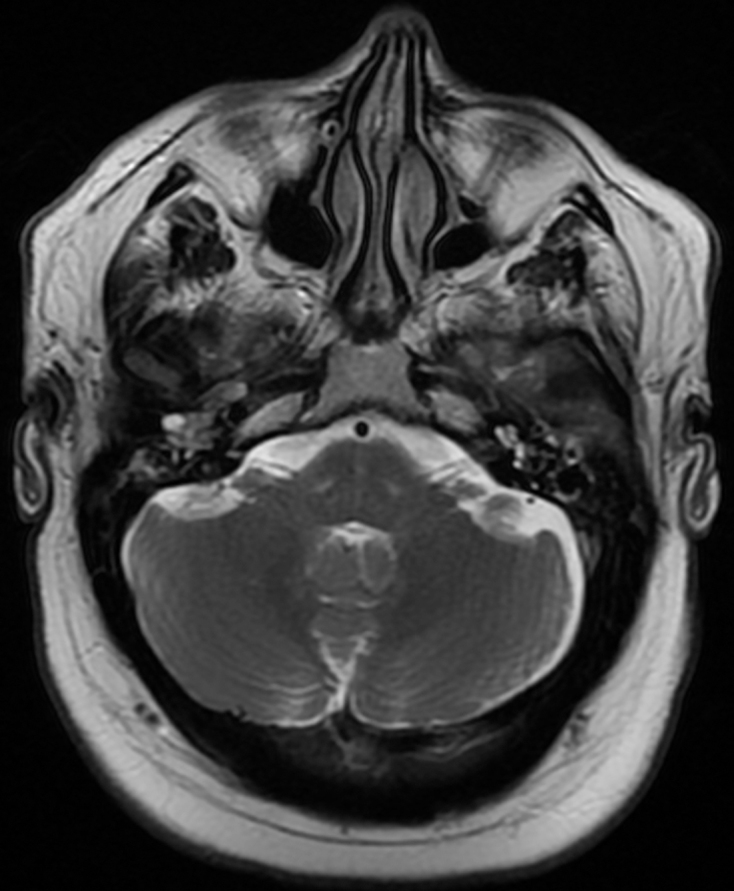

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the internal auditory meatus performed without contrast showed an enhancing soft tissue mass within the right middle ear cavity, extending through the proximal Eustachian tube towards the nasopharynx (Fig 2). It was in close proximity to the facial nerve canal and thin bony wall of the sigmoid sinus. Based on the radiological findings, a provisional diagnosis of a glomus tumour or extensive granulation tissue were hypothesised.

Figure 2.

Axial magnetic resonance image (T1 weighted, precontrast) of the internal auditory meatus, showing an enhancing soft tissue mass within the right middle ear cavity

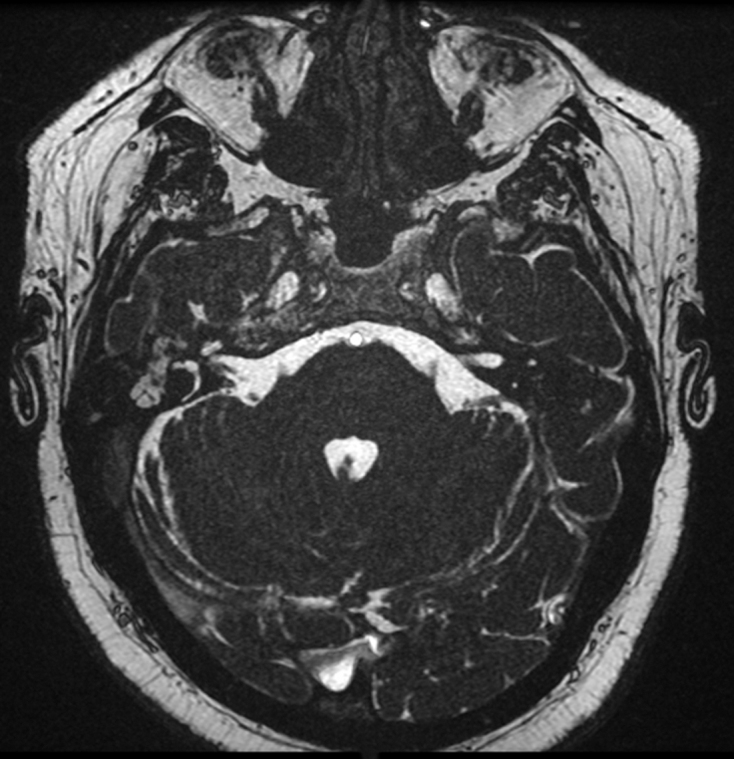

Diffusion-weighted MRI demonstrated intense enhancement of this lesion on the post-contrast scan, thus increasing the suspicion of a glomus tympanicum (Fig 3). CT angiogram, however, showed no enhancement within the middle ear, thus refuting the aforementioned diagnosis. There was also no evidence of a sigmoid sinus abnormality, such as thrombosis, arteriovenous malformation or diverticulum. The pulsatile nature of the tinnitus experienced by the patient is thought to arise as a result of increased awareness of blood flow through the sigmoid sinus. This was postulated to be influenced by several factors: the thin bony wall of the sigmoid sinus and the adjacent soft tissue mass serving as a conductive vector for vibrations from the sigmoid sinus to reach the cochlea.

Figure 3.

Axial magnetic resonance image (T2 3D acquisition, post-contrast) of the internal auditory meatus, showing post-contrast enhancement of right middle ear lesion

The patient underwent a modified radical mastoidectomy, with excision of the lesion from the middle ear and mastoid. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of Schneiderian papilloma of the middle ear. There was no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy. The specimen was not tested for human papillomavirus (HPV).

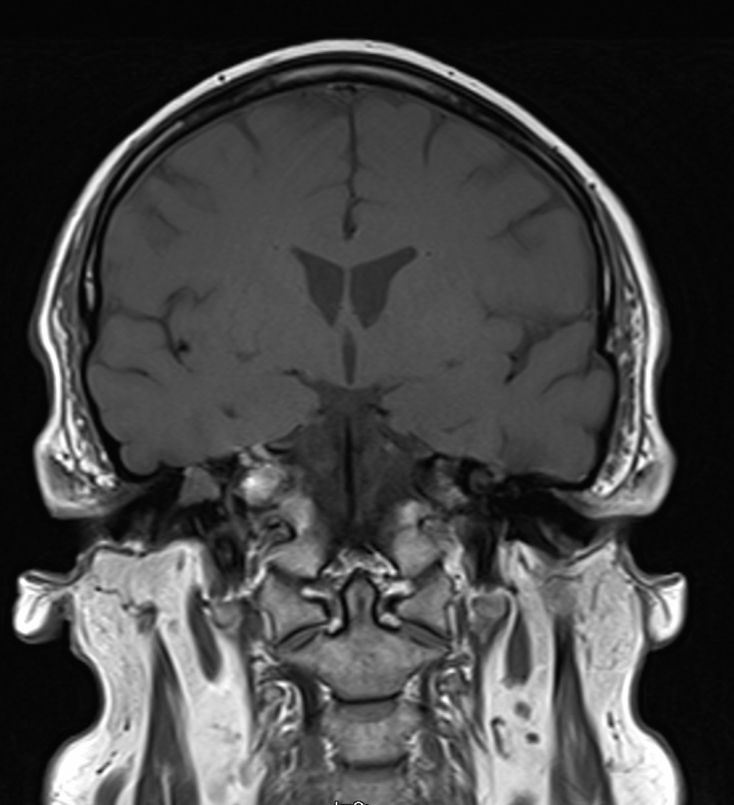

Two months postoperatively, the patient’s facial nerve palsy persisted at a House-Brackmann grade 3. He also had continuing pulsatile tinnitus, for which he was managed within the audiologist-led tinnitus clinic. A surveillance CT one-year postoperatively suggested a soft tissue mass within the right middle ear requiring further correlation with MRI. A subsequent MRI demonstrated a soft tissue density in keeping with postoperative changes, with no evidence of disease recurrence (Fig 4). The pulsatile tinnitus is being monitored for improvement as the postoperative inflammatory changes in the middle ear improve.

Figure 4.

Surveillance sagittal magnetic resonance image one year postoperatively, showing an inflammatory soft tissue density within the right middle ear cavity in keeping with postoperative changes

Discussion

Tinnitus as a presentation of ISP of the middle ear has only been described once in literature.6 There are no other published cases of this condition presenting with pulsatile tinnitus. This case highlights the importance of considering ISPs as a potential differential diagnosis in this type of presentation and emphasises the need for angiographic imaging to exclude a glomus tumour. The pulsatile nature of tinnitus may also highlight underlying sigmoid sinus abnormalities or anatomical variants which may affect later surgical intervention.

The aetiology of ISP of the middle ear remains unclear. Possible mechanisms include direct extension of sinonasal Schneiderian papillomas through the Eustachian tube.7 Another theory is of ectopic inclusion of ectodermal Schneiderian mucosa into the endodermally derived mucosa of the middle ear.8 Although histopathological features of ISP of the middle ear are identical to those for sinonasal disease,9 there is a high association with malignancy in middle ear ISP.

As in sinonasal disease, management of middle ear ISP is primarily surgical. The rate of recurrence is related to the extent of surgical resection.4 Mastoidectomy or temporal bone resection are sufficiently aggressive interventions to reduce recurrence rates by up to 61% when compared with simple excision.1 Radiotherapy is a valuable treatment option where risk of recurrence after surgery is high or, in the case of inoperable tumours, although there are limited data on which to assess treatment benefit. Resection of the middle ear ISP alone was not sufficient in improving the patient’s pulsatile tinnitus in this case; however, more published cases are required to comment on the potential efficacy of this intervention.

No classification systems currently exist specific to ISP to define the extent of disease and extent of resection. There is also no consensus on the role or timing of biopsies. Long-term follow up is a necessary arm of management. Average time to first recurrence was between two and six months with some patients having multiple lifetime recurrences requiring surgical re-exploration.10 MRI is recommended as follow-up imaging because of its higher sensitivity and specificity in differentiating recurrent tumour from adjacent inflammatory tissue when compared with CT.11,12

Middle ear Schneiderian papillomas are benign yet locally destructive lesions which pose a significant risk through erosion of middle ear structures, intracranial extension, involvement of cranial nerves and large vessels. Furthermore, ISP of the middle ear should be considered as a diagnosis in patients presenting with pulsatile tinnitus and a middle ear mass. These patients warrant aggressive disease resection to achieve clearance and long-term follow up with MRI is necessary to detect recurrence.

References

- 1.Schaefer N. Schneiderian-type papilloma of the middle ear: a review of the literature. 2015; (6): 989–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pou AM. Inverting papilloma of the temporal bone. 2002; (1): 140–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin F. Inverted papilloma of the middle ear. 2012; (4): 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Filippis C. Primary inverted papilloma of the middle ear and mastoid. 2002; : 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Putten L. Schneiderian papilloma of the temporal bone. 2013; : bcr2013201219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali RB, Amin M, Hone S. Tinnitus as an unusual presentation of Schneiderian papillomatosis. 2011; (2): 597–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone DM, Berktold RE, Ranganathan C, Wiet RJ. Inverted papilloma of the middle ear and mastoid. 1987; (4): 416–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenig BM. Schneiderian-type mucosal papillomas of the middle ear and mastoid. 1996; (3): 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D . Lyon: IARC press; 2005, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acevedo-Henao CM, Talagas M, Marianowski R, Pradier O. Recurrent inverted papilloma with intracranial and temporal fossa involvement: a case report and review of literature. 2010; (3): 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou H, Chen Z, Li H, Xing G. Primary temporal inverted papilloma with premalignant change. 2011; (2): 206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kainuma K, Kitoh R, Kenji S, Usami S. Inverted papilloma of the middle ear: a case report and review of the literature. 2011; (2): 216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]