Abstract

Purpose

To describe a case of disseminated cryptococcal meningitis with multifocal choroiditis and provide optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings correlated with described histopathology in a patient with advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Observations

The patient was a 54-year-old man with AIDS who presented with dyspnea and headache followed by acute vision loss. OCT demonstrated a lesion with a small area of fluid that was limited by a more prominent and irregular external limiting membrane with underlying nodular choroidal thickening, mild RPE disorganization, and hyperreflectivity of the overlying photoreceptor layer. Patient was found to have disseminated cryptococcal infection and passed away despite aggressive therapy. Autopsy was performed including bilateral enucleation and a Cryptococcus lesion was confirmed on histopathology.

Conclusion and importance

This case highlights the clinical, imaging, and histopathologic findings of cryptococcal choroiditis and provides a review of the updated treatment recommendations for disseminated infection in a patient with advanced AIDS. Although currently fundoscopy has proven most useful in directing the diagnostic algorithm in choroiditis in the setting of advanced immunosuppression, OCT may provide insight into the spread of Cryptococcus within the eye.

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcal choroiditis, Meningitis, HIV, AIDS, Clinicopathologic correlation

1. Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast found in dried pigeon excrement that is transmitted via aerosolization. Primary infection in immunocompromised hosts originates in the lungs with hematogenous dissemination to other organs including the skin, heart, joints, bones, eyes, brain, and meninges. Meningoencephalitis and meningitis are the most common manifestations of cryptococcosis, which portend a grim prognosis.1 Cryptococcal meningitis has a 90-day mortality rate of 9% in developed countries such as the US, East Asia, and Western Europe, but that rate jumps to 55% in Asia and South America and to 70% in Sub-Saharan Africa due to poor access to care and delayed treatment.2

Approximately 40% of patients with cryptococcal meningitis will develop ocular involvement. Kestelyn et al. described papilledema (32.5%), visual loss (9%), abducens nerve palsy (9%), and optic atrophy (2.5%) in 80 HIV patients with Cryptococcus neoformans infection.3 Although choroidal involvement is rare, Cryptococcus neoformans was reported as the most common cause of infectious choroiditis in patients with HIV, found in approximately 3% of patients at autopsy.4

We report a case of bilateral cryptococcal choroiditis in a patient with advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and provide optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings with histopathologic correlation.

2. Case report

A 54-year-old man with HIV diagnosed 21 years ago and a history of noncompliance with antiretroviral therapy was admitted to the hospital for dyspnea, weakness, and headache. His past medical history was also notable for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis requiring a six-drug treatment regimen, chronic hepatitis C, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), previously treated syphilis, oral thrush, anal condylomata, and peripheral neuropathy. On admission, his CD4 count was 7 cells/microliter, consistent with advanced AIDS. He was started on empiric treatment for community-acquired pneumonia and Pneumocystis pneumonia with ceftriaxone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and prednisone. In addition, he was started on MAC and fungal prophylaxis with azithromycin and fluconazole.

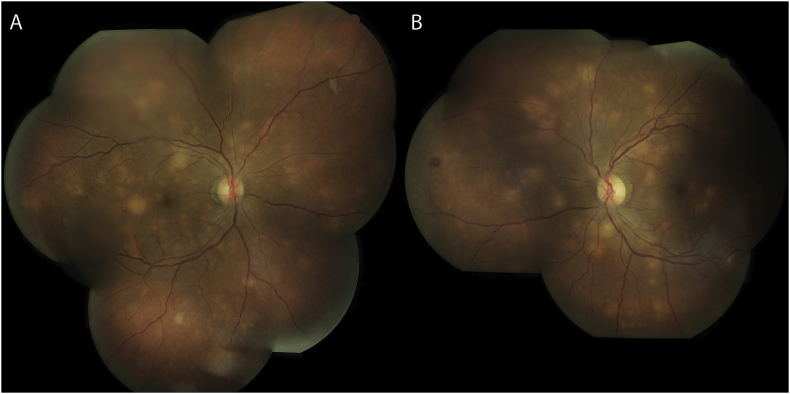

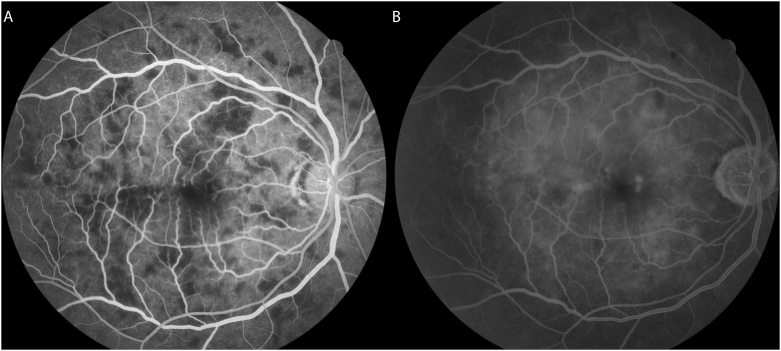

Several days after admission, he reported vision loss prompting an ophthalmology consult. Visual acuity was 20/50 with pinhole improvement in each eye. Pupils, extraocular motility, and intraocular pressure were unremarkable. Anterior slit lamp exam was also normal without anterior chamber or vitreous inflammation. Dilated fundus exam was notable for bilateral multifocal creamy yellow choroidal lesions of varying sizes distributed diffusely throughout the posterior pole, mild optic disc edema, and vascular tortuosity (Fig. 1). Fluorescein angiography revealed blocked choroidal filling of these lesions in early phases of the study (Fig. 2A) and showed either mild or no staining in late frames (Fig. 2B). The differential diagnosis remained broad at that time, but his presentation was highly suspicious for an infectious etiology.

Fig. 1.

Color fundus photographs of multifocal choroiditis. Color fundus photographs of the right eye (A) and the left eye (B) revealed bilateral multifocal creamy yellow choroidal lesions, mild optic disc edema, and vascular tortuosity. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Fluorescein angiogram of multifocal choroiditis. Fluorescein angiogram of the right eye showing early blockage of choroidal filling (A) mild late staining corresponding to these lesions (B).

Serologies for Histoplasma antigen, Toxoplasma IgG, and Coccidiodes Ab were negative and serum RPR titer of 1:2 was consistent with his previously treated Syphilis (prior titer 1:8). Serum Cryptococcus antigen was strongly positive (1:8192). Lumbar puncture revealed encapsulated yeast with positive Cryptococcus antigen (1:1024). Chest x-ray was notable for diffuse hazy opacities with bibasilar predominance. Bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial biopsy were positive for moderate round budding yeast, consistent with disseminated Cryptococcus neoformans infection.

The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin B (220 mg IV daily) and flucytosine (1500 mg orally four times daily) according to the guidelines for induction therapy for cryptococcal meningitis in HIV infected patients.2 Intravitreal amphotericin was also injected into both eyes (5 mcg/0.1 mL). Unfortunately, the patient continued to deteriorate despite broad antibiotic and anti-fungal therapy and succumbed to sepsis one week after presentation.

2.1. OCT and clinicopathologic correlation

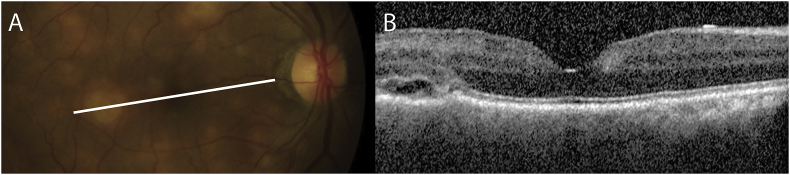

OCT over one of the lesions (Fig. 3), that was later confirmed to be cryptococcal choroiditis on histopathology, demonstrated a small area of fluid that was limited by a more prominent and irregular external limiting membrane with underlying nodular choroidal thickening, mild RPE disorganization and hyperreflectivity of the overlying photoreceptor layer. All the retinal layers above the lesions appeared mildly disrupted with an irregular contour although this may reflect the underlying disrupted contour of the outer retina.

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography findings of choroidal lesions. Optical coherence tomography of the right macula showing a section through one of the choroidal lesions seen on fundoscopy (A). Optical coherence tomography (B) showing a small area of fluid limited by a more prominent and irregular external limiting membrane. There is underlying nodular choroidal thickening, retinal pigment epithelium disorganization and hyperreflectivity of the overlying photoreceptor later.

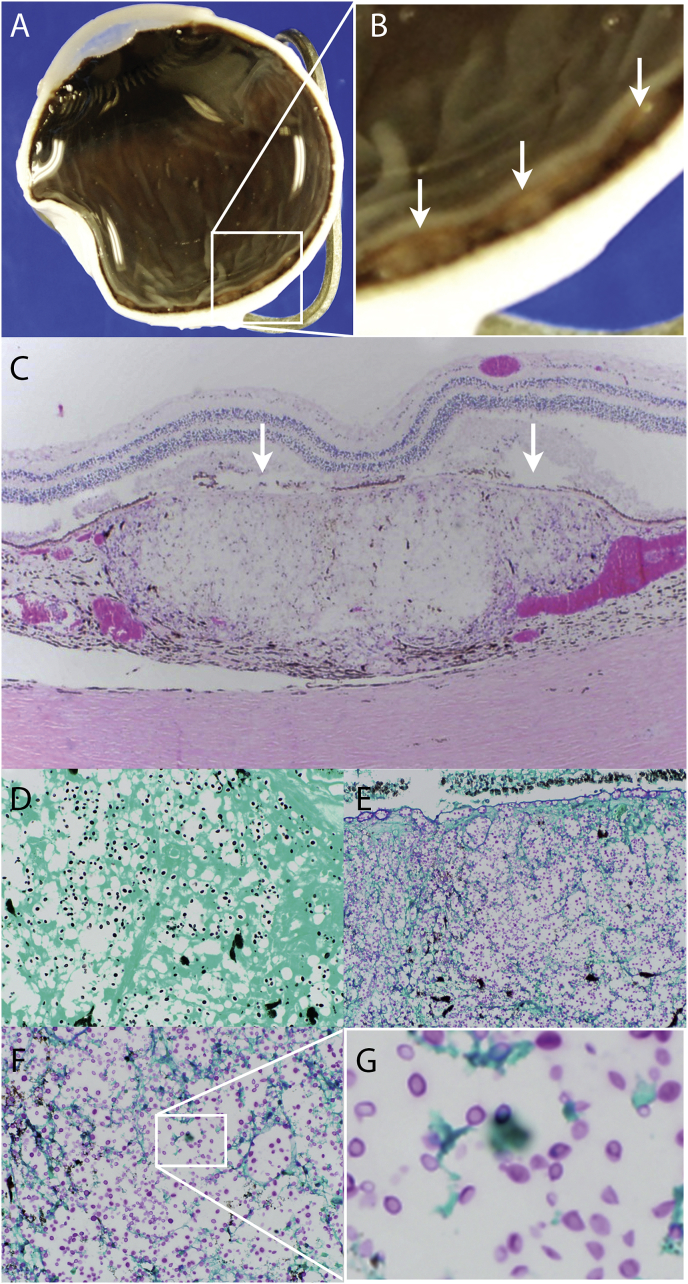

An autopsy was performed post-mortem included a bilateral enucleation. Grossly, both globes were notable for diffuse nodular choroidal infiltrates (Fig. 4A and B) that corresponded to the lesions noted on fundoscopy (Fig. 1). On hematoxalin and eosin stained sections, multiple lobular infiltrates were visible in the choroid which were devoid of normal choroidal vasculature (Fig. 4C). The retinal pigment epithelium overlying the lesions had was focally atrophic (Fig. 4C, arrows). At higher power, viable foamy histiocytes were seen infiltrating the choroid. Notably, there was no significant lymphoplasmacytic response in the choroid, retina, or vitreous, which is consistent with the patient's severe immunosuppression. Grocott's methanamine silver stain is positive for small round organisms within the histiocytic infiltrate (Fig. 4D). Periodic acid-Schiff stained sections revealed widespread small round organisms within the histiocytes. Of note, the blood vessels of the choriocapillaris are infiltrated with organisms (Fig. 4E), favoring hematogenous rather than leptomeningeal spread of the infection. Higher power (Fig. 4F) reveals small budding organisms with a prominent capsule (Fig. 4G), consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans infection.

Fig. 4.

Histopathology of choroidal lesion. Gross globe (A) with higher power (B) showing multifocal choroidal infiltrates (arrows). Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing artifactual separation of the retina from the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid and a full thickness nodular choroidal lesion devoid of normal choroidal vasculature (C). Grocott's methenamine silver stain of an adjacent section (D) reveals small round organisms within the histiocytes that stain positively for Periodic acid -Schiff (E). Higher power (F) reveals budding organisms with prominent capsules (G) consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans.

3. Discussion

Cryptococcal choroiditis has distinctive clinical features and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of multifocal choroiditis in immunocompromised patients. While Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common cause of infectious choroiditis in AIDS, review of 235 consecutive autopsies of AIDS patients (470 eyes) revealed cases of Pneumocystis carinii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, Histoplasma capsulatum, Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Toxoplasma gondii.4

The discrete choroidal lesions in cryptococcal choroiditis have a creamy yellow appearance and are distributed diffusely throughout the posterior pole, ranging in size from approximately 0.2 to 1.5 disc diameters.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 These lesions can also be accompanied by intraretinal, white-centered hemorrhages, as seen in our patient. Due to the profound immunosuppression associated with AIDS, there are often no other signs of intraocular inflammation in these infected eyes. Endophthalmitis, which can present with diffuse vitritis, haze, and expanding vitreous exudates, has been reported rarely and is thought to result from direct extension of a choroidal lesion into the retina and vitreous. These cases progress rapidly to vision loss and require aggressive treatment with intravitreal therapy and pars plana vitrectomy.6

On fluorescein angiography (FA), the cryptococcal lesions block choroidal filling in early arteriovenous phases and usually demonstrate mild staining in later phases. Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography has been shown to be more sensitive than FA in detecting choroidal lesions in cryptococcal infection,10,11 so this imaging modality may be useful when the fundus appearance is more subtle. OCT has also been used in cryptococcal choroiditis, which localized lesions to the inner choroid, consistent with histopathologic findings.11

The prevalence of cryptococcal choroiditis in the anti-retroviral era has declined and consequently there is little OCT description of Cryptococcus lesions. To the best of our knowledge, our case provides OCT images in the most advanced case of Cryptococcus choroiditis described along with histopathologic correlation. Previously described OCT findings include an increased hyperreflectivity of the photoreceptor layer with underlying discrete choroidal thickening with a normal RPE11 and a small area of subretinal fluid and underlying choroidal plaque but with normal overlying retina architecture.12

In our case, OCT revealed that the external limiting membrane was faint away from the lesion but becomes much more prominent and irregular overlying the lesion. Given this finding, one could imagine the ELM functioning as a barrier to prevent spread of infection into the inner retina and vitreous. This ELM is not a true membrane but is actually a series of intermediate junctions (zonulae adherentes) between photoreceptor inner segments and the apical processes of the Müller cells. These junctions constitute the inner border of the subretinal space and serve as a barrier to diffusion of large molecules into and out of this space.13 There is a lack of OCT descriptions of other types of infectious choroiditis in patients with advanced AIDS, as most reports of the condition were from prior to the OCT era. Since the OCT findings in Cryptococcus choroiditis are non-specific, they cannot be used to reliably distinguish between infectious entities based solely on OCT.

Cryptococcus neoformans usually infects the choroid by hematogenous spread to choroidal vasculature. Leptomeningial spread is also possible in cases of cryptococcal meningitis, though this is less commonly reported.3 Histological examination of our patient reveals organisms packed within the choriocapillaris, supporting hematogenous seeding as the likely route of infection. It is not surprising, therefore, that the underlying choroid appears thickened on OCT.

Prompt treatment for cryptococcal meningitis must be initiated given the high mortality rate. In HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis, an induction regimen of amphotericin B (0.7–1.0 mg/kg/day) and flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) should be given for 2 weeks, followed by 8 weeks of consolidation treatment with fluconazole 400 mg daily, and 200 mg daily thereafter until HIV is controlled by antiretroviral therapy. Systemic therapy alone has resulted in resolution of choroidal lesions in several case reports,7,14 but intravitreal injection of amphotericin B (5 μg) should be considered if lesions fail to improve. Henderly et al.6 reported a case of cryptococcal chorioretinitis and endophthalmitis in which pars plana vitrectomy and intravitreal injection stopped progression of vision loss, and the authors credit the intraocular therapy with saving ambulatory vision in that eye.

While immunosuppression is a risk factor for this opportunistic infection, antiretroviral therapy must be initiated judiciously for cryptococcal meningitis. Patients with advanced AIDS are at risk for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is an overwhelming inflammatory response to infection as the host immune system is restored. In a randomized study of HIV infected patients with cryptococcal meningitis, Boulware, et al.15 assigned patients to either prompt (1–2 weeks) or delayed (5 weeks) initiation of ARV, and found significantly decreased mortality in the deferred treatment group (30% versus 46%). IRIS can also damage the eye. Shulman et al. reported a case of subretinal abscess causing retinal detachment in the setting of initiation of antiretroviral therapy that required vitrectomy and retinectomy.16

Even with appropriate treatment, cryptococcal meningitis is a deadly disease with high mortality rate.2 Since cryptococcal choroiditis is not infrequently found in HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis, and since choroidal lesions may be the first manifestation of disseminated disease or meningitis, it is critical to initiate a prompt and thorough workup when choroidal lesions are seen.

4. Conclusion

This case highlights the clinical, imaging, and histopathologic findings, and provides a review of the updated treatment recommendations for disseminated cryptococcal infection in a patient with advanced AIDS. Because cryptococcal choroiditis was mostly characterized in the pre-antiretroviral era, few OCT findings with correlated histopathology have been previously noted. Thus, the presentation of such combined findings may shed light on the route of spread of this infection within the eye.

Patient consent

Patients sibling provided consent, orally, post the passing of the patient.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding

1) Heed Ophthalmic Foundation Fellowship and 2) J. Arch McNamara Memorial Fund (both CMA).

Conflict of interest

JMS is a consultant for FSV4.

CMA, IRG, DLC, MMB, AO have no financial disclosures.

Authorship

All authors attest to satisfying the ICMJE criteria for Authorship.

Acknowledgments

None.

Contributor Information

Christopher M. Aderman, Email: caderman@midatlanticretina.com.

Ian R. Gorovoy, Email: gorovoy.ian@gmail.com.

Daniel L. Chao, Email: dlchao@ucsd.edu.

Michele M. Bloomer, Email: michele.bloomer@ucsf.edu.

Anthony Obeid, Email: aobeid@midatlanticretina.com.

Jay M. Stewart, Email: jay.stewart@ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Ellis D.H., Pfeiffer T.J. Ecology, life cycle, and infectious propagule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Lancet. 1990;336(8720):923–925. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92283-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan D.J., Parris V. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology and therapeutic options. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:169–182. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S38850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kestelyn P., Taelman H., Bogaerts J. Ophthalmic manifestations of infections with Cryptococcus neoformans in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116(6):721–727. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morinelli E.N., Dugel P.U., Riffenburgh R., Rao N.A. Infectious multifocal choroiditis in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(7):1014–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31543-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney M.D., Combs J.L., Waschler W. Cryptococcal choroiditis. Retina. 1990;10(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderly D.E., Liggett P.E., Rao N.A. Cryptococcal chorioretinitis and endophthalmitis. Retina. Summer 1987;7(2):75–79. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198700720-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma S., Graham E.M. Cryptococcus presenting as cloudy choroiditis in an AIDS patient. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(6):618–619. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.6.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine H.F., Chang M.A., Dunn J.P., Jr. Bilateral cryptococcal choroiditis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(11):1726–1727. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.11.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreola C., Ribeiro M.P., de Carli C.R., Gouvea A.L., Curi A.L. Multifocal choroiditis in disseminated Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(2):346–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arevalo J.F., Fuenmayor-Rivera D., Giral A.E., Murcia E. Indocyanine green videoangiography of multifocal Cryptococcus neoformans choroiditis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Retina. 2001;21(5):537–541. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200110000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baillif S., Delas J., Asrargis A., Gastaud P. Multimodal imaging of bilateral cryptococcal choroiditis. Retina. 2013;33(1):249–251. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318271f290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady C., Regillo C. A case of cryptococcal choroiditis. Retin Physician. 2012;9:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milam A.H., Smith J.E., John S.K. Anatomy and cell biology of the human retina. In: Duane T.D., Tasman W., Jaeger E.A., editors. Duane's Ophthalmology on CD-ROM. vol. 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2006. 2006 ed. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muccioli C., Belfort Junior R., Neves R., Rao N. Limbal and choroidal Cryptococcus infection in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120(4):539–540. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72677-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulware D.R., Meya D.B., Muzoora C. Timing of antiretroviral therapy after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shulman J., de la Cruz E.L., Latkany P., Milman T., Iacob C., Sanjana V. Cryptococcal chorioretinitis with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17(5):314–315. doi: 10.3109/09273940903003505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]