Abstract

Angiosarcoma (AS) is an uncommon malignant neoplasm characterized by rapidly proliferating, extensively infiltrating anaplastic cells derived from blood vessels. These are aggressive tumors and tend to recur locally, spread widely with high rate of lymph node and systemic metastases. They are more frequent in skin and soft tissue, head and neck being the most common sites. Here we report a case of metastatic AS affecting lower extremity in an elderly patient on a background of chronic lymphedema due to filariasis (Stewart–Treves syndrome).

Keywords: Cutaneous angiosarcoma, lower extremity, Stewart–Treves syndrome

Introduction

Angiosarcoma (AS) is an aggressive malignant tumor of vascular endothelial origin that comprises approximately 2% of soft tissue sarcomas. The disease is most commonly seen in elderly with male predisposition. Predisposing factors for AS include trauma, chronic lymphedema, irradiation, and age (more common in the elderly population) and obesity. Head and neck are the most commonly affected sites. Typical manifestations of AS have been described as raised purplish-red papules, rosacea-like lesions,[1] and bruise-like lesions. Due to the variability in the appearance of AS, the correct diagnosis can often be delayed.

Case History

A 64-year-old male presented for evaluation of multiple red nodules on left leg associated with bleeding since 4 months. Patient had history of progressively increasing chronic lymphedema for the past 10 years. Lesions started on lymphedematous left leg as multiple nodular lesions that used to bleed on trivial trauma, which within 4 months increased in size and number. There was history of profuse bleeding from the lesion with foul smelling discharge. Patient had undergone multiple skin biopsies in the past and was diagnosed to have infected capillary hemangioma. Ultrasonography of local part revealed multiple heterogeneous ill-defined hypoechoic areas with vascularity. Patient had received treatment with systemic antibiotics in view of repeated infections without significant improvement.

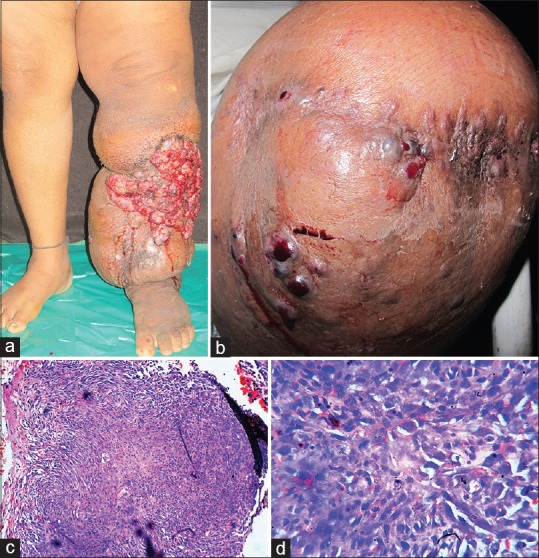

Cutaneous examination revealed elephantiasis of left lower extremity with multiple hemorrhagic nodules present on the anterio-lateral aspects of left leg [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) Elephantiasis of left lower extremity with multiple hemorrhagic nodules on the antero-lateral aspects. (b) Recurrence of multiple hemorrhagic nodulo-ulcerative lesions on the amputation stump. (c) Skin biopsy from the lesion revealed a mass in the deep dermis, consisting of anastomosing blood vessels with endothelial lining showing multiple atypical cells and pleomorphism (×100, H and E). (d) Blood vessels with endothelial lining showing multiple atypical cells and pleomorphism (×400, H and E)

In view of anemia due to bleeding from lesions and recurrent infections, above knee amputation was carried out that led to significant relief to the patient. After 2 months, patient presented with recurrence of lesions at the site of amputation stump.

Cutaneous examination revealed multiple hemorrhagic nodulo-ulcerative lesions on the amputation stump [Figure 1b]. Skin biopsy from the lesion revealed a mass in the deep dermis, consisting of anastomosing blood vessels with endothelial lining showing multiple atypical cells and pleomorphism. Immunohistochemistry was not done due to financial constraints [Figure 1c and d]. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed metabolically active soft tissue mass with cortical destruction of lower end of left femur and metabolically active external iliac lymph nodes on both the sides. ELISA for HIV 1 and 2 was nonreactive. Hence final diagnosis of metastatic AS developing in chronic lymphedema, that is, Stewart–Treves syndrome (STS) was made. Patient was started on palliative chemotherapy with paclitaxel injections. Even after seven cycles of chemotherapy there was no significant improvement. Patient stopped therapy and ceased to follow up.

Discussion

AS is a rare and aggressive malignant tumor of vascular endothelial origin comprising approximately 2% of soft tissue sarcomas. Among all cases of AS, one third occurs in the skin, one fourth in soft tissue, and the remainder in other sites.[2]

Due to variable clinical scenarios that may be associated with this tumor, different presentations are seen, for example, lymphedema-associated AS, radiation-induced AS, primary breast AS, AS of the soft tissue, and cutaneous angiosarcoma (CA).[3] Factors that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this tumor include radiation, lymphedema, vascular insufficiency, ulceration, and chemicals such as vinyl chloride, arsenic, and thorium dioxide.[4] However, approximately 78–95% of CA arise with no predisposing factors. CA usually affects the head and the neck (with scalp involvement in 50% of cases), they are infrequent in the lower extremity. CA occurs most often in patients over the age of 60, with a M/F sex ratio of 2.5 to 3:1.[5]

Clinically, CAs usually present as nodules or angiomatous, erythematous, and purplish plaques, which may be confused with hematoma, hemangioma, localized inflammatory edema, rhinophyma, purpuric patches, keratotic lesions, verrucous lesions, Kaposi sarcoma (multiple hemorrhagic sarcoma), Kaposi-like hemangioendothelioma, angiolymphoid hyperplasia, Kimura's disease, amelanotic melanoma or pyogenic granuloma. AS arising in an area of chronic lymphedema is referred to as STS. Stewart and Treves first described lymphangiosarcoma occurring in post-mastectomy lymphedema of the arm in 1948. AS arising in a chronically lymphedematous leg is rare.

In the majority of patients, the AS is relatively large (at least 10 cm in diameter) at the time of presentation because of a significant delay in diagnosis.[6] The incidence of STS is low. The prevalence has been estimated at between 0.45% and 0.07% of patients treated for early carcinoma of the breast.[7] STS in the lower extremity is reported only occasionally. STS typically develops after 10–15 years latency and accounts for approximately 5% of ASs.

The accumulation of protein rich interstitial fluid alters the local immune response within the affected limb and stimulates lymphangiogenesis for the development of collateral vessels. Because immune surveillance is compromised, lymphedema creates an immunologically vulnerable milieu for the development of malignancy, specifically vascular tumors.[8]

The histologic findings of AS in STS show a proliferation of irregular anastomosing vascular channels that dissect dermal collagen. The malignant endothelial cells lining these channels are hyperchromatic and pleomorphic with large nucleoli and frequent mitosis. The tumor cells are round to ovoid with a predominantly epithelioid and spindle-shaped morphology. Overlying epidermis may be acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, or atrophic, with or without proliferation of reticular fibers in the dermis. A large percentage of ASs stain positive for CD31 and CD34, of which, CD31 is the more sensitive and specific of the two. Cytokeratin stains may be positive in some epithelioid ASs.[9,10]

Histopathologically, early lesions of CAS should be differentiated from benign vascular proliferation and Kaposi's sarcoma.

Differentiation from benign vascular proliferations depends on recognition of cellular atypia, presence of crowding of lining cells and of solid papillary clusters of cells, and irregular interconnecting pattern of vessels. There is strong expression of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) in benign endothelial tumors and greatly decreased expression in AS.

Kaposi's sarcoma is characterized by spindle cell proliferation with mild nuclear atypia, low mitotic activity, vascular slits, and extravasated RBCs. The tumor tends to grow around large vessels and follow lymphangitic distribution. The tumor cells show moderate to diffuse positivity for CD31, CD34, and Human Herpes Virus (HHV)-8.

AS on the other hand is characterized by a proliferation of atypical cells lining anastomosing vessels that strongly react with vascular endothelial markers such as factor VIII-related antigen, CD31, and CD 34.

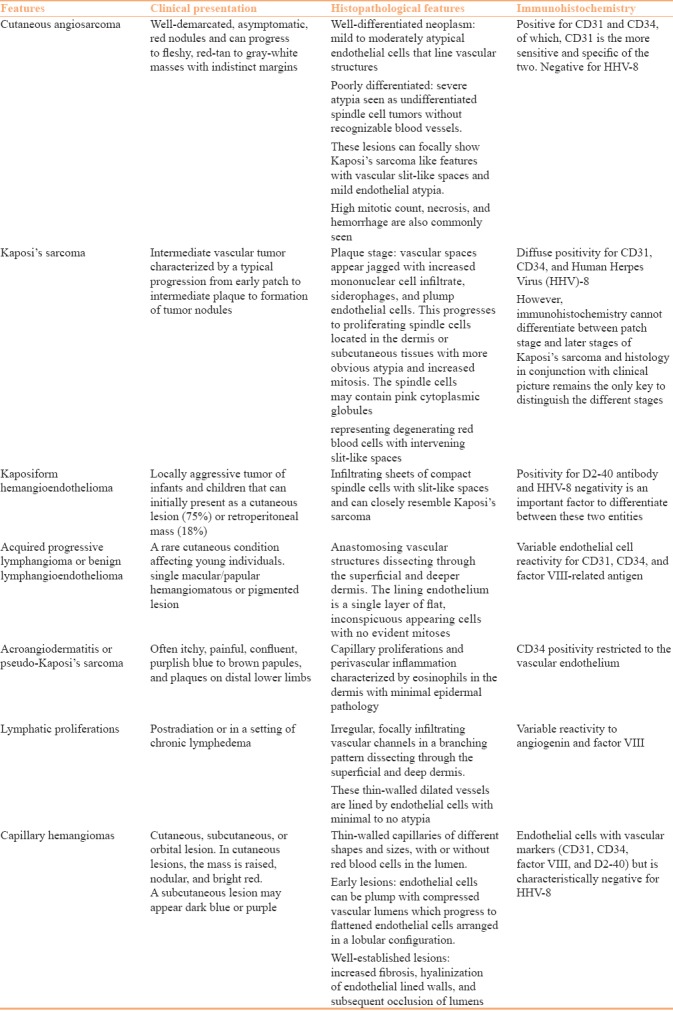

Differentiation of CA from other benign and malignant vascular and lymphatic proliferation is discussed in Table 1.[11]

Table 1.

Differentiating features benign and malignant vascular and lympho-proliferative neoplasm

Treatment depends upon the general health of the patient, tumor location, histologic subtype, and extent of involvement. Localized and advanced cutaneous disease is frequently treated similarly with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by wide local excision or amputation and radiation therapy.[9] Additional therapeutic options for locally advanced disease include the use of loco-regional modalities such as isolated limb perfusion, limb infusion, and electrochemotherapy.[12]

Prognosis of CA is poor regardless of subtype and treatment offered. Depending on the modality of treatment, local recurrences have been observed in 35–86% of cases.[13] The proclivity for distant pulmonary metastases has been well-documented.[14] Survival rates range from 51% at 5 years to 43% at 10 years. Patients with localized disease have a better overall outcome with 5- and 10-year survival rates of 62% and 54%, respectively. Those with distant metastasis have a 6.2% chance of survival at both 5 and 10 years.

We present this case to highlight the rare location and presentation of AS on the lower extremity with metastatic AS, multiple recurrences, and poor response to chemotherapy.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mentzel T, Kutzner H, Wollina U. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face: Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of a case resembling rosacea clinically. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:837–40. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagao K, Suzuki K, Yasuda T, Hori T, Hachinoda J, Kanamori M, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the buttock complicated by severe thrombocytopenia: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:903–7. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathes EF, Frieden IJ. Vascular tumors. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, Folpe AL, editors. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. St. Louis Mo USA: Mosby; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanus DM, Kelsen D, Clark DG. Radiation induced angiosarcoma. Cancer. 1987;60:777–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870815)60:4<777::aid-cncr2820600412>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbs CP, Peabody TD, Mundt AJ, Montag AG, Simon MA. Oncological outcomes of operative treatment of subcutaneous soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79:888–96. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinclair SA, Sviland L, Natarajan S. Angiosarcoma arising in a chronically lymphedematous leg. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:692–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzpatrick PJ. Lymphangiosarcoma in breast cancer. Can J Surg. 1969;12:172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruocco V, Schwartz RA, Ruocco E. Lymphedema: An immunologically vulnerable site for development of neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:124–7. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan MB, Swann M, Somach S, Eng W, Smoller B. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: A case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.10.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohsawa M, Naka N, Tomita Y, Kawamori D, Kanno H, Aozasa K. Use of immunohistochemical procedures in diagnosing angiosarcoma. Evaluation of 98 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:2867–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2867::aid-cncr2820751212>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kak I, Salama S, Gohla G, Naqvi A, Alowami S. A case of patch stage of Kaposi's sarcoma and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Rare Tumors. 2016;8:6123. doi: 10.4081/rt.2016.6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campana LG, Valpione S, Tosi A, Rastrelli M, Rossi CR, Aliberti C. Angiosarcoma on lymphedema (Stewart–Treves syndrome): A 12-year follow-up after isolated limb perfusion, limb infusion and electrochemotherapy. Case Rep Oncol. 2016;9:205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa K, Takahashi K, Asato Y, Yamamoto Y, Taira K, Matori S, et al. Treatment and prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: A retrospective analysis of 48 patients. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e1127–33. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31655219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa M, Tanaka I, Takemura T, Matsubara O, Kasuga T. Angiosarcoma of the scalp: Report of two cases with fatal pulmonary complications and a review of Japanese autopsy registry data. Virchows Archive. 1987;412:83–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00750735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]