Abstract

This study investigates the role of age of acquisition (AoA), socioeducational status (SES), and second language (L2) proficiency on the neural processing of L2 speech sounds. In a task of pre-attentive listening and passive viewing, Spanish-English bilinguals and a control group of English monolinguals listened to English syllables while watching a film of natural scenery. Eight regions of interest were selected from brain areas involved in speech perception and executive processes. The regions of interest were examined in 2 separate two-way ANOVA (AoA × SES; AoA × L2 proficiency). The results showed that AoA was the main variable affecting the neural response in L2 speech processing. Direct comparisons between AoA groups of equivalent SES and proficiency level enhanced the intensity and magnitude of the results. These results suggest that AoA, more than SES and proficiency level, determines which brain regions are recruited for the processing of second language speech sounds.

Keywords: language, speech, perception, bilingualism, neuroscience, development

The goal of this fMRI study was to investigate the effect of L2 age of acquisition (AoA), socioeducational background (SES), and L2 proficiency on the patterns of brain activity elicited by second language speech syllables in a group of Spanish-English bilinguals and a control group of English monolinguals. More precisely, this study investigates how learning the phonology of a second language early or late in life, growing up in a family with a high or low socioeducational status, and having a high or low proficiency level in the second language impact the neural processing of second language speech sounds. Eight brain regions were selected for analysis based on their involvement in speech perception and executive processes in bilinguals.

Age of acquisition and proficiency in the second language are two factors widely known to determine the ultimate attainment of a second language (Cummins, 1979; Hernandez & Li, 2007). In phonological learning specifically, early learners of a second language usually display more native-like patterns of L2 perception than late learners but a high proficiency level in late learners is also known to improve perception of second language sounds (Archila-Suerte, Zevin, Bunta, & Hernandez, 2011). Socieconomic status, which tends to correlate with socioeducational background, has recently emerged as a potential confounding variable in studies conducted with bilingual populations because many bilingual communities in the United States belong to minority groups of lower social standing. Here we examine how these three factors potentially influence neural processing of second language speech sounds in the regions of interest selected.

Investigating the neural processes underlying speech perception in bilinguals is a preliminary step towards understanding how bilingual perception impacts cognition. Much research has been dedicated to understanding the effects of bilingualism on cognition and neural processing, especially in the realm of attention and inhibition (Bialystok, 2011; Bialystok, Craik, & Luk, 2008) but no studies have investigated the effect of bilingual perceptual knowledge on neural processing. That is, no studies have investigated how the perceptual mechanisms reshaped by the knowledge of two phonologies – where such L2 perceptual knowledge varies depending on the individual's AoA and proficiency – impacts neural processing of L2 sounds. Many studies have examined the effects of stimuli (e.g., distance between L1 and L2 sounds, perceptual weighting of acoustic cues) on perception (Best, McRoberts, & Goodell, 2001; Best, McRoberts, & Sithole, 1988; Nittrouer, 1996), examined the decline in perception for non-native speech sounds throughout early childhood (Kuhl et al., 2008; Werker & Tees, 1984), and the retention of perceptual sensitivity for non-native contrasts in bilinguals (Albareda-Castellot, Pons, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2011; Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2005; Sundara, Polka, & Genesee, 2006); but to our knowledge, there have been no studies that take into account participants' characteristics (AoA, SES, and proficiency) to investigate how these factors impinge on the neural processing of L2 sounds. One fMRI study conducted by Perani and colleagues (1998) took into consideration AoA and proficiency to examine overall representation of the first and second language, but the study was not specific to the domain of speech perception. A recent study by Kilman and colleagues (2014) examines the effect of language proficiency on speech perception in noise but it does not take AoA or SES into consideration. It is important to understand the neural processes underlying speech perception in bilinguals because future applied research can investigate how bilingual perception impacts other linguistic skills and language development.

1.1. Early Acquisition in L2 Speech Perception

Behaviorally, it is known that infants' ability to accurately perceive non-native speech declines rapidly in the first year of life (Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens, & Lindblom, 1992; Werker & Tees, 1983). However, even though these first few months are crucial to the development of native speech perception, infants continue to refine their perceptual abilities throughout childhood, adolescence, and even young adulthood (Hazan & Barrett, 2000; Sundara et al., 2006; Sundara, Polka, & Molnar, 2008; Walley & Flege, 1999). For instance, bilingual infants who are continually exposed to two languages can maintain the ability to differentiate between L1 and L2 contrasts (Byers-Heinlein, Burns, & Werker, 2010; Sebastián-Gallés & Bosch, 2009). This ability to differentiate between L1 and L2 contrasts may be explained by children's acute perception of within-category and between-category phonemes. It has been found that early bilingual adults are able to ignore the irrelevant acoustic differences that exist between exemplars of the same phonemic L2 sound (e.g., hat – hat) and able to distinguish the phonetically meaningful differences that exist between exemplars of different L2 sounds (e.g., hat-hot) (Archila-Suerte et al., 2011). Even though the development of non-native speech perception in early bilinguals may not be linear (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2005), monolinguals and early bilinguals share a similar perceptual ability in the discrimination of speech sounds (Mayo, Florentine, & Buus, 1997). In this study, monolinguals and early bilinguals are not expected to differ in the perception of English phonemes through the production of words outside the scanner that match the syllables presented in the scanner because early bilinguals were exposed to the second language early in life and have been exposed to a considerable amount of English throughout life.

In this study, we selected the bilateral superior temporal gyrus (STG) as a region of interest because of its involvement in auditory perception. Comprehensive studies have mainly identified the posterior STG (p-STG) as the primary region involved in the processing of basic spectrotemporally complex sounds (i.e., speech) in comparison to complex nonspeech sounds, tones, noise, and silence (Benson et al., 2001; Binder et al., 2000; Celsis et al., 1999; Golestani & Zatorre, 2004; Vouloumanos, Kiehl, Werker, & Liddle, 2001; Zevin & McCandliss, 2005). Additionally, studies of skill acquisition and expertise have shown that certain regions of the brain are engaged according to the sensory phenomena associated with the task. For example, if the task has a visual component such as in reading, occipital lobe regions that process this type of sensory input are recruited (Poldrack, Desmond, Glover, & Gabrieli, 1998). On the other hand, if the task has a motor component, such as in dancing, premotor regions are recruited (Calvo-Merino, Glaser, Grèzes, Passingham, & Haggard, 2005). It has also been found that brain activations tend to be more intense in experts relative to novices; as in the case of face experts or athletes who respectively show increased activity in the fusiform gyrus or motor areas of the brain relative to novices (Gauthier, Tarr, Anderson, Skudlarski, & Gore, 1999; Wright, Bishop, Jackson, & Abernethy, 2010). Taking together the neuroimaging fidings in speech perception and sensory processing in skilled individuals, we expect monolinguals and early bilinguals – as speech perception experts of English sounds – to show increased activity in the bilateral superior temporal gyrus relative to late bilinguals of equivalent SES and L2 proficiency level.

1.2. Late Acquisition in L2 Speech Perception

The speech learning process is thought to be different for individuals who learn the second language in adulthood. If the second language is learned late in life when L1 categories are established, L2 sounds that are highly similar to L1 sounds become assimilated by pre-exisiting L1 categories whereas L2 sounds that are different from any L1 phonemic category create new categories (Best & McRoberts, 2003). Even though late acquisition of a second language has been traditionally associated with poor perception and production of L2 speech (Scovel, 1988), late acquisition does not necessarily impede the ability to perceive non-native speech properly. Despite the difficulties that listeners may have acquiring the phonology of a second language in adulthood, accurate learning of non-native speech can occur if there is abundant L2 input and the listener's attentional resources are directed to L2 speech (Flege, 2003; Flege, Bohn, & Jang, 1997). There tends to be ample variability in the perception of L2 sounds in late bilinguals (Marinova-Todd, Marshall, & Snow, 2000). Improving the perception of L2 speech not only requires heightened attention to the new speech sounds but also practice with articulatory movements so the late learner has the opportunity to try out tongue placement and precise motor timing (Klein, Zatorre, Milner, Meyer, & Evans, 1994), just as articulatory interventions are done with bilingual children displaying phonological errors (Holm, Dodd, & Ozanne, 1997). In the present study, late bilinguals are expected to have more production errors than early bilinguals and monolinguals in the behavioral task outside the scanner thus indirectly indicating that late bilinguals tend to have more inaccuracies in the perception of L2 sounds.

The motor theory of speech perception proposes that perception depends on the procedural recoding of the sounds as articulatory movements (Liberman & Mattingly, 1985). Recent fMRI studies have now demonstrated that the motor system is recruited in tasks of speech perception (Wilson, Saygin, Sereno, & Iacoboni, 2004). More specifically, the rolandic operculum has surfaced as an area heavily involved in articulation of speech sounds because it contains part of the ventral portion of the somatotopic tongue representation (S. Brown et al., 2009; S. Brown, Ngan, & Liotti, 2008). The constant monitoring of what is being produced seems never to be sufficiently fine-tuned in most late bilinguals (Simmonds, Wise, & Leech, 2011). In order to see improvements in the long-term motor representations of articulation, late bilinguals must remain aware of their tongue movements and vocalizations. This internal awareness of L2 sounds and articulations may be an alternative way to learn the new speech sounds as there is no explicit babbling stage in L2 for late learners. Based on the involvement of the bilateral rolandic operculum in speech perception and production, we selected it as a region of interest to investigate brain activity elicited by L2 speech sounds in monolinguals, early, and late bilinguals. In particular, late bilinguals are expected to show greater activity in the rolandic operculum bilaterally relative to early bilinguals and monolinguals when listening to L2 speech syllables because of internal replay the L2 sounds.

2.1. High Language Proficiency in L2 Speech Perception

As mentioned above, late bilinguals experience more difficulties perceiving and producing the speech sounds of a second language. However, it has been demonstrated that a high L2 proficiency level predicts improved perception of between-category speech sounds (Archila-Suerte et al., 2011). That is, highly proficient bilinguals can learn to distinguish between two phonemes of different L2 categories (e.g., hat-hot), especially if the L2 sound is markedly different from any L1 sound (Best et al., 2001; Fox, Flege, & Munro, 1995; Iverson et al., 2003). This phenomenon observed in highly proficient bilinguals appears to result from increased attention to speech (Archila-Suerte et al., 2011; Flege et al., 1997). Some types of training paradigms, where attention is directed to the relevant speech cues, can in fact facilitate non-native speech learning in adults (Aliaga-Garcia & Mora, 2009; McCandliss, Fiez, Protopapas, Conway, & McClelland, 2002; McClelland, Fiez, & McCandliss, 2002). Due to the inadvertent increased attention directed to speech sounds, highly proficient bilinguals are expected to have more accurate production of specific L2 speech sounds than low proficient bilinguals.

An individual's ability to correctly perceive L2 sounds may be predicted by neuroanatomical differences of the left insula/prefrontal cortex, left temporal lobe, and bilateral regions of the parietal lobe (Golestani et al., 2006; Golestani, Molko, Dehaene, LeBihan, & Pallier, 2007). Several imaging studies of selective attention to speech have shown activity in the inferior parietal lobule in response to listening to syllables or continuous speech (Hugdahl et al., 2000; Pugh et al., 1996; Sabri et al., 2008; Von Kriegstein, Eger, Kleinschmidt, & Giraud, 2003), althouth this region has also been observed in older bilingual children (8-10 yrs) passively listening to L2 syllables (Archila-Suerte, Zevin, Ramos, & Hernandez, 2013). The inferior parietal lobule appears to be involved in other domains of language, besides speech perception, that require attention. For example, studies with bilinguals report activity in the inferior parietal lobule in grammatical and semantic tasks (Ding et al., 2003; Perani & Abutalebi, 2005; Perani et al., 1998; Wartenburger et al., 2003). Taking together the results from these studies, it appears that the involvement of the inferior parietal lobule is essential in the neural processing of speech sounds in bilinguals. Based on this literature, we have selected the region of the inferior parietal lobule bilaterally to examine brain activity evoked by L2 syllables. We expect highly proficient bilinguals to show increased activity in this region relative to low proficient bilinguals because of heightened pre-attentive perceptual mechanisms involved in L2 speech processing.

Another region of interest selected for analysis was the bilateral middle frontal gyrus. This region of the prefrontal cortex has been associated with processes of executive function, including manipulation and short-term storage of information (Cohen et al., 1997). Because of its involvement in working memory and its role in fronto-lateral networks of attention (Vincent, Kahn, Snyder, Raichle, & Buckner, 2008), studies with bilinguals report this to be one of the regions involved in language switching (Luk, Green, Abutalebi, & Grady, 2011; Wang, Xue, Chen, Xue, & Dong, 2007) and inhibitory control (Bialystok et al., 2005). It has been reported that activity in the middle frontal gyrus is stronger and more sustained in individuals with more efficient working memory processes relative to individuals with less efficient processes (Pessoa, Gutierrez, Bandettini, & Ungerleider, 2002). However, the literature regarding neural processing efficiency in cognitive tasks is unclear. Several studies have also reported increased activity in frontal and parietal areas in individuals who perform less proficiently in tasks of orthography, lexico-semantic decisions, and sentence production (Golestani et al., 2006; Hernandez, Hofmann, & Kotz, 2007; Hernandez & Meschyan, 2006; Xue, Dong, Jin, & Chen, 2004). These studies suggest that increased activity represents increased mental effort. Therefore, the literature in attention suggest that highly proficient bilinguals will show increased activity in the bilateral inferior parietal lobule and middle frontal gyrus relative to low proficient bilinguals due to heightened and superior attentive processes. On the other hand, the literature in L2 proficiency suggest that low proficient bilinguals will show increased activity in these regions relative to highly proficient bilinguals but this time due to mental exertion and controlled processing.

2.2. Low Language Proficiency in L2 Speech Perception

Low proficient bilinguals tend to intermix and overlap phoneme exemplars from different categories by not correctly identifying where the phonemic boundary lies (Archila-Suerte et al., 2011). The literature points to phonological working memory as a key element in L2 learning success (Doughty et al., 2010) and it appears that poor phonological working memory affects how L1 and L2 speech sounds are processed because difficulties with native speech perception predict worse performance of non-native speech (Diaz, Baus, Escera, Costa, & Sebastian-Galles, 2008). Behaviorally, low proficient bilinguals are expected to have more inaccurate production of specific English phonemes outside the scanner, thereby indicating problems of L2 perception, than highly proficient bilinguals. Furthermore, given the studies in neural efficiency aforementioned, low proficient bilinguals may show increased activity in fronto-parietal regions due to labored and conscious processing of speech sounds. If, on the other hand, high proficient bilinguals show increased activity in fronto-parietal regions due to heightened pre-attentive processes, then low proficient bilinguals are not expected to show surviving areas of activation relative to high proficient bilinguals in the bilateral inferior parietal lobule and bilateral middle frontal gyrus.

3.1 Socioeducational differences

Although socioeconomic status has been found to impact the development of the prefrontal cortex (Noble & Farah, 2013), with monolingual children from higher SES typically showing increased activity in frontal regions of the brain, we do not expect to see a main effect of SES that supersedes the effect of AoA or proficiency. This hypothesis is derived from the long-standing literature on AoA and proficiency in second language acquisition which have repeatedly indicated the importance of these two factors for second language learning, including L2 speech sound learning (Flege, 1995; Flege & Liu, 2001; Flege, Munro, & Mackay, 1995; Piske, MacKay, & Flege, 2001). It has been reported that bilingualism can counteract the negative effects of poverty (Engel de Abreu, Cruz-Santos, Tourinho, Martin, & Bialystok, 2012). If the data presented here supports these recent fidings of bilingualism serving as a protective factor to combat the negative effects of economic and educational disadvantage, then we should observe increased activity in the bilateral middle frontal gyrus of low SES bilinguals relative to low SES monolinguals.

In this article we show the patterns of brain activity in monolinguals, early, and late bilinguals with equivalent levels of SES and English language proficiency in response to listening to English speech syllables. Bilinguals' ability to correctly perceive L2 phonemes is essential to learning speech which is in turn fundamental to developing other higher-level linguistic skills. This is of great importance in academic environments where language learning difficulties related to listening and reading comprehension observed in bilinguals may originate from their inability to perceive L2 speech properly.

Method

Participants

There were 82 participants in this study. Sixty-six (66) participants were Spanish-English bilinguals and 16 participants were English monolinguals. Bilinguals were divided into two groups: early bilinguals (AoA < 9 yrs) and late bilinguals (AoA > 10 yrs). The early bilingual group was composed of 34 participants (9 males, 25 females) and the late bilingual group was composed to 32 participants (15 males, 17 females). In the early bilingual group, there were 23 participants born in the US and 11 participants born outside the US. In the late bilingual group, there were 5 participants born in the US and 27 participants born outside the US. For those born outside the country, the mean length of residency in the US was 9 years (SD = 5.5). Sixty-nine (69) percent of bilinguals were of Mexican descent. Several other Spanish-speaking countries from South America were represented in the minority. There was no systematic cultural difference within the group of bilinguals that exerted a confounding effect on the perception of second language speech sounds.

The average age of second language acquisition in early bilinguals was 5.6 years of age. None of the early bilinguals were exposed to English from birth. The earliest exposure to English in the group of early bilinguals was 3 years of age. All late bilinguals had been exposed to English an average of 9.32 years at the time of testing. The mean age of early bilinguals was 22.9 years (SD = 5.04) and the mean age of late bilinguals was 26.5 years (SD = 5.75). The cutoff of 9 years of age was chosen to classify bilinguals as early or late based on the literature of second language acquisition which deems a second language to be more successfully acquired before puberty (Newport, 1990).

All monolinguals (6 males, 10 females) were of Caucasian descent. All but two participants were born in the United States. The two participants born outside the country moved to the US during early childhood. The mean age of the monolingual group was 24.4 yrs (SD = 4.5). See Table 1 for a summary of these demographics. All participants were right-handed according to the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971), did not report a history of language or speech-related disorders, and consented to the criteria stipulated in the protocol approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Houston.

Table 1.

| Spanish-English bilingual (n= 66) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| English monolinguals (n= 16) | Early bilinguals - AoA < 9 years (n =34) | Late bilinguals - AoA > 10 years (n =32) | |

| Mean age | 24.4 (4.5) | 22.9 (5.04) | 26.5 (5.75) |

| Mean years of education | 16.37 (4.61) | 16.58 (3.04) | 17.93 (3.26) |

| Mean grade point average (GPA) | - | 2.83 (1.01) | 2.41 (1.35) |

| Mean English Proficiency | 75.76 (11.4)* | 69.92 (8.79)* | 64.85 (10.62)* |

| Mean Spanish Proficiency | - | 67.31 (10.83)** | 74.99 (7.11)** |

| Mean parental socioeducational s | 3.65 (1.06) | 2.22 (1.20) | 2.85 (1.36) |

| Bilingual subjects born in the US (Bilingual subjects born outside the US(n =38) | |||

| Mean years of education | 16.67 (3.24) | 17.65 (3.14) | |

| Mean grade point average (GPA) | 2.77 (1.10) | 2.52 (1.27) | |

| Mean English Proficiency | 69.59 (8.21) | 65.89 (10.94) | |

significant at p < 0.05

significant at p < 0.001

Stimuli

Recordings of natural speech of the English syllables saf (/sæf/ as in hat), sof (/sɒf/ as in hot), and suf (/s∧f/ as in hut) were obtained from an adult male monolingual English speaker in a sound-attenuated room. One hundred and twenty tokens (40 tokens for each syllable type) were digitized at 44,100 Hz using a Sony MZ-NH800 mini-disc recorder and a Sony ECM-CS10 stereo microphone. Once recorded, Praat software (Boersma, 2001) was used to normalize peak amplitude to ensure audibility of all stimuli. Each syllable was paired with another syllable to create a trial for the fMRI task (e.g., saf-saf; saf-sof; saf-suf; sof-sof; sof-suf; suf-suf). The six combinations of paired syllables times the number of tokens recorded per syllable resulted in participants listening to a variety of stimuli throughout the task. The English voiceless fricatives /s/ and /f/, with the random acoustic noise that characterizes them, were used to aid the recognition of the vowel within the syllable. The English vowels /æ/, /ɒ/, and /∧/ were chosen as the stimuli for this study because Spanish-English bilinguals tend to overlap and assimilate these phonemic categories onto the Spanish phoneme /a/ (e.g., casa) thereby making these sounds difficult for Spanish-English bilinguals to discriminate (Flege et al., 1995). See (Bradlow, 1995) for a detailed list of vowel formants across the two languages or (Archila-Suerte et al., 2013) for the list of durations and frequencies of the syllables used in the present study.

Procedure

Behavioral assessment

In order to assess participants' global language proficiency in English and Spanish, the tests of picture vocabulary, listening comprehension, and verbal analogies from the standardized Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery – Revised (WLPB-R) were selected. (Woodcock, 1991). Participants named pictures of objects for the test of picture vocabulary, filled-in-the-blank incomplete sentences for listening comprehension, and provided the word that properly established a relationship between items for the test of verbal analogies (e.g., you cut with scissors and you write with______). All tests gradually increased their level of difficulty. The test of picture vocabulary measured participants' ability to produce language and the test of listening comprehension along with verbal analogies measured participants' ability to understand language. The combined tests evaluated participants' overall linguistic competence. These same tests were selected from the Spanish version of the Woodcock-Munoz Language Proficiency Battery (Woodcock & Muñoz-Sandoval, 1995) to assess bilingual participants' proficiency in Spanish. The items in each of the tests of the English and Spanish versions were equated for length, frequency, and difficulty. None of the items were identical across languages.

Speech recordings

Participants read 144 English words that targeted the production of the same vowel sounds heard during the fMRI task (/æ/, /ɒ/, /∧/); for example: gas, sad, lot, job, lunch, and cup. These words were read outside the scanner. All recordings were obtained in Praat with an external tabletop microphone (Omnidirectional Condenser, MX391/0). The purpose of these recordings was to inspect the perception of English syllables through the production of the target phonemes. Even though the recordings indirectly measured perception, the literature has demonstrated close mappings between perception and production of speech (Wilson & Iacoboni, 2006; Wilson et al., 2004). After the recordings, four English monolingual judges assessed the intelligibility of the speech samples by transcribing what they heard and rating the level of foreign accent of each speaker using a 9-point scale (1 = No Foreign Accent, 9 = Very Strong Foreign Accent)

Experimental task and fMRI Design

The task implemented in this study included pre-attentive listening of English speech syllables along with passive viewing of a muted non-captioned film that displayed natural scenery (i.e., Planet Earth). Participants listened to blocks of syllable pairs of saf, sof, and suf through MRI-compatible headphones while the film played throughout the entire duration of the scan. Planet Earth was selected because it did not include verbal material, which prevented potential interference with the language task of pre-attentive listening. All participants reported not having seen the film before the study. Participants were instructed to focus their attention on the film while the sounds played in the background.

A pre-attentive listening paradigm enabled us to examine basic perceptual processes while directing attentional engagement to an unrelated visual stimulus. Minimizing the use of executive processes like attention and working memory was important to prevent the use of higher-order cognitive strategies that could lead to attending to extra-phonetic cues that may overestimate the performance of bilinguals (Best et al., 1988; Zevin & McCandliss, 2005). At the end of the scan, participants were asked to describe some of the scenes observed in the film to verify alertness during the task (e.g., what animals did you see? what were the animals doing?). All participants were able to describe the images viewed, thus confirming that they were awake and attending to the film during the brain scan. No particular scenes from the film were selected; instead, all participants watched the first half of the film.

The fMRI task had a block design that presented 5 trials of the same condition in a row. Each trial consecutively presented two English syllables (e.g., saf – saf) during a scanner silent interval between brain volume acquisitions. During the silent interval the scanner noise was reduced by delaying the initiation of the pulse sequence with a Repetition Time (TR) delay. This prevented the scanner noise from tainting the speech signal. To further ensure the quality of data acquisition, participants were asked whether they could hear the syllables clearly before starting the task. The duration of each experimental trial was 1.42 seconds. This included 510 ms of syllable duration, 150 ms of padded silence at the beginning and at the end of each trial, and an inter-stimulus (ISI) duration of 100 ms. Appended to the experimental trial was the brain image acquisition time (TA) of 1.58 s, for a total trial duration of 3 seconds. Since each experimental block contained 5 trials, each block lasted 15 seconds. An additional 12-second block of scanner silence where no auditory stimuli were presented served as baseline condition. The baseline condition only contained the visual stimulus of the muted film. Therefore, baseline and experimental blocks alternated in the following way: film (baseline), speech syllables + film, film (baseline). The speech sounds were presented in a single fMRI run that lasted 27 minutes. Participants listened to multiple exemplars of the syllable pairs in a sequence of blocks that followed the same order (See Archila-Suerte, et al., 2012 for a graphic depiction of the fMRI design)

fMRI Data Acquisition

Brain imaging data was acquired with a 3T Siemens Trio scanner and a 12-channel radiofrequency head coil at the Human Neuroimaging Laboratory of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. A Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequence was used to acquire 3D anatomical images with a T1-weighted contrast. We used a TR of 1200 ms, an in-plane resolution of 1 mm × 1 mm, and a slice thickness of 1 mm with a field of view (FoV) of 87.5% (matrix of 256 × 256). Anatomical images were acquired in ascending sequential order in the axial plane. An Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) sequence was used to acquire functional data. We used a TR of 3000 ms, a TR delay of 1420 ms for the scanner silent interval, a 90 degree flip angle, and a voxel size of 3.4 × 3.4 × 5 mm. Twenty-six slices per volume were acquired in an interleaved descending order in the axial plane. To optimize the timing synchronization between the task and the scanner, we used in-house NEMO software (Network Experiment Management Objects)

fMRI data analyses

Data were analyzed with Statistical Parametric Mapping, SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London), using a block design specification for our statistical model. The preprocessing of the functional data included slice-timing and motion correction, corregistration of anatomical to functional images, tissue segmentation, normalization of data into MNI stereotaxic space, and smoothing of data to enhance signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR). For slice-timing correction, the median slice of the interleaved descending acquisition was used as the reference slice. A rigid body transformation minimized the errors introduced by head motion in realignment. The motion parameters were then modeled as confounds at the first-level of analysis. Spatial smoothing used an 8 mm full-width half maximum Gaussian Kernel. The stimulus presentation onsets for each condition were modeled with a canonical hemodynamic response function and a high-pass filter of 128 seconds. Simple linear contrasts of all the conditions (speech syllable pairs and baseline) were conducted at the first level of analysis in order to enable complex between-group comparisons at the second level of analysis. Since the results of the present study did not show any differences in brain activity between paired syllables that were the same (e.g., saf-saf) and paired syllables that were different (e.g., saf-sof) or vice versa, a global condition labeled all English syllables that combined all speech syllable conditions was created. This global condition was contrasted with baseline at the first level and then contrasted across groups of AoA, SES, and proficiency at the second level. Including the variables of AoA, SES, and proficiency in 2-way fMRI ANOVA analyses enabled the examination of main effects and interactions. Moreover, it enabled detailed direct comparisons between AoA groups of equivalent SES or equivalent proficiency which other studies may not be able to examine due to the small sample of participants recruited.

At the second level of analysis, two separate 2-way ANOVA's were conducted on eight independent regions of interest (ROI) which derived from four homologous areas in each hemisphere. The ROI's were extracted using the SPM toolbox WFU_PickAtlas (Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft, & Burdette, 2003). Because of the reduced brain area being examined in each ROI, type I error is reduced and this allows more liberal intensity and cluster magnitude thresholds to be used (intensity peak α < 0.05, cluster size k > 20). Unlike whole-brain analysis that require family-wise-error (FWE) correction due to the voxel-by-voxel testing of the null hypothesis, ROI analysis conducts an average of the timeseries of all the voxels in the ROI thereby allowing contrasts with a probability of p < 0.05 to be considered statistically significant. The eight ROI's extracted were the bilateral superior temporal gyrus, bilateral rolandic operculum, bilateral middle frontal gyrus, and bilateral inferior parietal lobule. These brain areas have been reported in the literature to be important for speech perception and executive function in bilinguals.

The first ANOVA examined the main effect of age of acquisition and socioeconomic status (i.e., AoA × SES) and their interaction in a whole-brain analysis (FWE-corrected p < 0.05). This grand analysis was followed up by in-depth analyses of each region aforementioned (unc. p < 0.05) to compare AoA groups (monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals) across levels of SES (low SES, high SES). Similarly to the first ANOVA, the second ANOVA examined the effect of age of acquisition and L2 proficiency (i.e., AoA × L2 proficiency) and their interaction in a whole-brain analysis (also FWE-corrected, p < 0.05). This analysis was also followed up by ROI analyses to compare AoA groups (early and late bilinguals) across levels of proficiency. Monolinguals were excluded from this second ANOVA examining AoA × L2 proficiency because the monolingual group was highly proficient in English and could not be reliably split into two separate proficiency groups. Moreover, comparing L1 proficiency in monolinguals vs. L2 proficiency in bilinguals raises some theoretical concerns regarding the time allotted to become proficient in English. More specifically, monolinguals have built proficiency on the same language over the years whereas bilinguals have split their time over the years to build proficiency on two languages. This makes the comparison between L1 proficiency in monolinguals and L2 proficiency in bilinguals imbalanced and inadequate.

Results

Behavioral Results

Monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals had a comparable number of years of education completed F(2, 79) = 1.64, p = 0.20 and similar scholastic ability given their grade point average F(2,79) = 2.01, p = 0. 14. The groups significantly differed in socioeducational status (SES) F(2,79) = 7.42, p < 0.001. In order to account for these differences in the neuroimaging data, the first ANOVA model examined the main effects of AoA and SES. More importantly, in-depth comparisons between AoA groups equated on SES were examined to reveal any potential confounding effects of the latter. Participants were considered to be of low SES if the maximum level of parental education attained was less or equal than a high school degree and of high SES if the maximum level of parental education was college or an advanced degree.

For second language proficiency (i.e., English), the three measures of picture vocabulary, listening comprehension, and verbal analogies were strongly correlated (picture vocabulary and listening comprehension r = 0.536, p < 0.001; picture vocabulary and analogies r = 0.547, p < 0.001; listening comprehension and analogies r = 0.532, p < 0.001, two-tailed); therefore, a composite score was calculated to use one score as a global measure of English proficiency. The combination of strongly correlated measures into one factor is statistically appropriate and a common approach employed in factor analysis and structural equation modeling (Bollen, 2005). Monolinguals obtained significantly higher scores than early bilinguals and late bilinguals in English proficiency (monolinguals vs. early bilinguals F(1, 48) = 3.95, p < 0.05; monolinguals vs. late bilinguals F(1, 46) = 10.69, p = 0.002). Yet, early bilinguals were significantly better than late bilinguals in English proficiency F(1, 64) = 4.46, p < 0.03. See Figure 1, panel A. These differences in English proficiency between monolinguals and bilinguals were expected given that monolinguals were tested in their native language and bilinguals were tested in their second language. In Spanish proficiency, late bilinguals were significantly more proficient than early bilinguals F(1, 64) = 11.43, p < 0.001. This result was also expected because late bilinguals were exclusively raised in Spanish-speaking environments until late childhood. See Figure 1, panel B. Early and late bilinguals were classified as low proficient in English if their individual composite score fell below the mean of their corresponding group and as high proficient if their score fell above the mean of their corresponding group. Proficiency classification took into consideration the group to which the individual belonged (early or late) to adjust for timing in L2 age of acquisition. For example, highly proficient late bilinguals may not be as proficient as early bilinguals but their scores are high relative to other members of the same late bilingual group.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs of average performance in English and Spanish language assessments across groups of English monolinguals, and Spanish-English early and late bilinguals. Error bars represents standard error.

There were no significant differences between bilingual participants born in the US vs. bilingual participants born outside the US, F(1, 64) = 2.25, p = 0.13. Any potential difference between bilinguals born in the US and bilinguals born outside the US is explained by the variable of AoA because AoA and birthplace are significantly correlated r = 0.52, p < 0.001.The variable of birthplace is tightly linked to AoA because age of acquisition represents the age at which the participant became immersed in the second language, which coincides with the age US-born bilinguals began elementary school (early bilinguals) or the age of arrival to the country (late bilinguals). Since the differences between bilinguals who were born in the US and bilinguals who were born outside the US closely align with the groupings of early and late, the results do not change if the groupings are re-arranged as born-in-the-US vs. born-outside-the-US.

Speech recordings

Five participants who completed the fMRI task had a corrupted speech recording or did not have a speech recording at all. Monolinguals, early, and late bilinguals did not differ in the production of words containing the phonemes of /æ/, /ɒ/, and /∧/ F(2,74) = 2.06, p < 0.13. That is, judges rated monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals to produce L2 words similarly. See Figure 2. Therefore, all bilingual participants had typical auditory and articulatory processes that allowed them to perceive and produce sounds in the L2 sufficiently accurately according to native listeners. All three groups significantly differ in overall foreign accent F(2,74) = 23.37, p < 0.001. In foreign accented English, early bilinguals were marginally different from monolinguals F(1,45) = 4.74, p < 0.035 and late bilinguals were significantly different from early bilinguals F(1, 61) = 27.00, p < 0.001 and from monolinguals F(1, 61) = 25.78, p < 0.001. English proficiency in bilinguals was inversely correlated with overall foreing accent r = -0.628, p < 0.001 indicating that higher L2 proficiency is associated with better perception and production of non-native speech sounds. Subgrouping early and late bilinguals as high proficient and low proficient also did not show significant differences in the production of any of the target phonemes (/æ/: F(1, 61) = 1.0, p = 0.31; for /ɒ/: F(1,61) = 0.17, p = 0.67; for /∧/: F(1,61) = 0.06, p = 0.80).

Figure 2.

Bar graphs of average performance in the production of English words between groups of English monolinguals, and Spanish-English early and late bilinguals. Error bars represents standard error.

Although mean parental socioeducational background differed between monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals F(2, 79) = 7.42, p < 0.001, socioeducational background did not have an effect on how accurately English words were produced outside the scanner as groups of low SES and high SES performed similarly (/æ/: F(8, 68) = 1.21, p = 0.302, /ɒ/: F(8,68) = .598, p = .776, /∧/: F(8,68) = 1.01, p = .432)

fMRI Results

1.1 Whole-brain analysis in AoA × SES ANOVA

A whole-brain analysis, family-wise error (FWE) corrected p < 0.05 with a magnitude threshold k = 20, showed no main effect of AoA, or SES, or an interaction.

1.2 Region of interest analyses in AoA × SES ANOVA (unc. p < 0.05, k = 20)

1.2.1 Bilateral superior temporal gyrus (right hemisphere ROI from 60 -38 20 to 58 -6 -10; left hemisphere ROI from -58 -38 20 to -50 -2 10)

There was an interaction between AoA and SES in the right and left superior temporal gyrus. The interactions were examined through discrete comparisons between AoA groups of equivalent SES. Monolinguals showed increased activity in the left and right superior temporal gyrus relative to early bilinguals of equivalently low or high SES. Similarly, late bilinguals showed increased activity in the bilateral superior temporal gyrus relative to early bilinguals of equivalent SES. On the contrary, early bilinguals did not show any increased activity in either hemisphere of the superior temporal gyrus relative to monolinguals or late bilinguals of the same SES. See Table 2 for a detailed list of cluster sizes and peaks of activation by group comparison in each ROI examined in the AoA × SES ANOVA.

Table 2. Region of interest analyses ANOVA AoA × SES.

| Superior temporal gyrus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Interaction AoA × SES | left | 26 | F = 4.56 | -46 4 -14 |

| 45 | F = 4.06 | -46 -30 6 | ||

| 31 | F = 3.66 | -58 -16 2 | ||

| Interaction AoA × SES | right | 168 | F = 5.12 | 56 -20 2 |

| Monolinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | left | 44 | 2.42 | -42 -42 18 |

| Monolinguals of high SES > Early bilinguals of high SES | left | 234 | 2.78 | -60 -26 16 |

| 52 | 2.77 | -48 4 -14 | ||

| Monolinguals of high SES > Early bilinguals of high SES | right | 533 | 3.4 | 64 -38 10 |

| 69 | 2.87 | 58 -2 -8 | ||

| 25 | 2.04 | 64 -18 8 | ||

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | left | 266 | 2.88 | -52 -8 -2 |

| 73 | 2.16 | -60 -28 4 | ||

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | right | 95 | 2.49 | 64 -28 18 |

| Late bilinguals of high SES > Early bilinguals of high SES | left | 1185 | 3.94 | -44 -26 12 |

| Late bilinguals of high SES > Early bilinguals of high SES | right | 1186 | 3.55 | 56 -20 6 |

| Rolandic operculum | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | left | 175 | 2.72 | -62 -8 10 |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | right | 173 | 2.88 | 62 -12 14 |

| Late bilinguals of high SES > Monolinguals of high SES | left | 238 | 2.4 | -48 -18 12 |

| Late bilinguals of high SES > Monolinguals of high SES | right | 282 | 2.51 | 52 -20 10 |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | left | 151 | 2.54 | -42 -28 16 |

| 72 | 2.25 | -52 -2 14 | ||

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | right | 37 | 2.73 | 62 -12 14 |

| 35 | 1.94 | 46 -22 18 | ||

| Late bilinguals of high SES > Early bilinguals of high SES | left | 191 | 3.75 | -42 -26 12 |

| 119 | 2.63 | -56 -6 8 | ||

| Late bilinguals of high SES > Early bilinguals of high SES | right | 219 | 3.41 | 48 -18 14 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Interaction AoA × SES | left | 2275 | F = 15.78 | -24 16 50 |

| Interaction AoA × SES | right | 1567 | F = 14.27 | 28 18 50 |

| Early bilinguals of low SES > Late bilinguals of low SES | right | 36 | 2.06 | 36 36 22 |

| Early bilinguals of high SES > Late bilinguals of high SES | right | 162 | 2.77 | 22 14 46 |

| 178 | 2.56 | 30 46 16 | ||

| 40 | 2.55 | 30 50 -2 | ||

| Early bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | left | 1938 | 4.32 | -26 14 50 |

| Early bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | right | 1865 | 4.09 | 34 40 36 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | left | 1455 | 5.96 | -50 -52 42 |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | right | 1015 | 5.32 | 48 -56 42 |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | left | 391 | 3.46 | -36 -64 50 |

| Late bilinguals of low SES > Early bilinguals of low SES | right | 37 | 2.21 | 26 -48 50 |

| 25 | 2.19 | 58 -48 38 | ||

| Early bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | left | 875 | 4.53 | -52 -50 42 |

| Early bilinguals of low SES > Monolinguals of low SES | right | 880 | 4.61 | 48 -56 42 |

1.2.2 Bilateral rolandic operculum (right hemisphere ROI from 44 -18 20 to 54 8 0; left hemisphere ROI from -42 -18 20 to -54 -2 10)

There were no interactions between AoA and SES in the bilateral rolandic operculum. Late bilinguals showed increased activity in the right and left rolandic operculum relative to monolinguals and early bilinguals of parallel SES. On the other hand, neither monolinguals nor early bilinguals showed increased activity in the right or left rolandic operculum relative to late bilinguals.

1.2.3 Bilateral middle frontal gyrus (right hemisphere ROI from 36 10 60 to 36 56 0; left hemisphere ROI from -30 14 60 to -40 52 0)

There was an interaction between AoA and SES in the right and left middle frontal gyrus. As with the superior temporal gyrus, the interactions were closely studied through specific comparisons between AoA groups. Early bilinguals showed increased activity in the right middle frontal gyrus relative to late bilinguals of equivalent high or low SES. Additonally, early bilinguals showed increased activity in the right and left middle frontal gyrus relative to monolinguals but only when the groups were of parallel low SES.

1.2.4 Bilateral inferior parietal lobule (right hemisphere ROI from 42 -48 50 to 46 -48 40; left hemisphere ROI from -44 -48 60 to -48 -44 40)

Between group comparisons revealed increased activity in the bilateral inferior parietal lobule of late bilinguals relative to monolinguals and early bilinguals of equivalent low SES. Early bilinguals also showed increased activity in the region bilaterally relative to monolinguals of low SES. Figure 3A and 3B contain the fMRI images of the group comparisons in AoA × SES ANOVA.

Figure 3A.

Region of interest analyses in the bilateral superior temporal gyrus and bilateral rolandic operculum in AoA × SES ANOVA. Group comparisons in each ROI at the second level of analysis (e.g., early bilinguals vs. late bilinguals) contrast the conditions of English syllables vs. baseline. Comparisons show brain activity between groups of equivalent socioeducational background (SES). Yellow: high SES; Blue: low SES. Brain areas colored in green in panel A of the bilateral superior temporal gyrus ROI display the specific coordinates that increased in activation in the bilateral STG depending on AoA and SES. ROI p-value < 0.05, cluster size k < 20.

Figure 3B.

Region of interest analyses in the bilateral middle frontal gyrus and bilateral inferior parietal lobule in AoA × SES ANOVA. Group comparisons in each ROI at the second level of analysis contrast the conditions of English syllables vs. baseline. The same color conventions as Figure 3A are employed here. ROI p-value < 0.05, cluster size k < 20.

2.1 Whole brain analysis in AoA × L2 proficiency ANOVA

A whole-brain analysis, family-wise error (FWE) corrected p < 0.05 with a magnitude threshold k = 20, showed no main effect of AoA, or L2 proficiency, or an interaction.

2.2 Region of interest analyses in AoA × L2 proficiency ANOVA (unc. p < 0.05, k = 20)

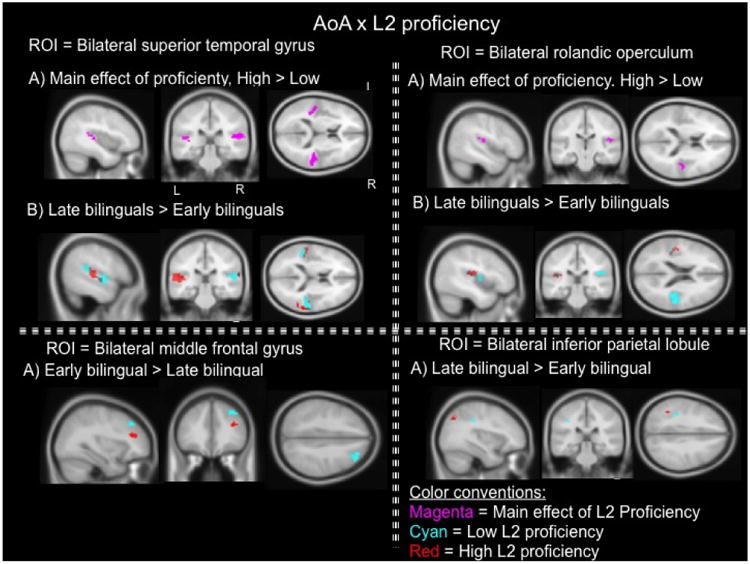

2.2.1 Bilateral superior temporal gyrus

There was a main effect of proficiency in the right and left superior temporal gyrus where high proficient bilinguals showed increased activity in the regions compared to low proficient bilinguals. The reverse contrast of low proficiency relative to high proficiency did not display voxels of suprathreshold activity. Effects of AoA in this second ANOVA resembled the pattern of findings reported in the first ANOVA (AoA x SES) examining the ROI of the bilateral superior temporal gyrus; that is, late bilinguals showed increased activity in the superior temporal gyrus relative to early bilinguals of equivalent high or low proficiency level. See Table 3 for a detailed list of group comparisons in each ROI examined in the AoA × L2 proficiency ANOVA.

Table 3. Region of interest analyses ANOVA AoA × L2 proficiency.

| Superior temporal gyrus | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Main effect of L2 proficiency | left | 54 | F = 5.2 | -50 -26 10 |

| High proficiency > Low proficiency | left | 148 | 2.28 | -50 -26 10 |

| Main effect of L2 proficiency | right | 199 | F = 10.41 | 46 -26 14 |

| High proficiency > Low proficiency | right | 290 | 3.23 | 46 -26 14 |

| Late bilingual low proficient > Early bilingual low proficien | left | 470 | 3.9 | -52 -8 -2 |

| 331 | 2.56 | -54 -36 18 | ||

| Late bilingual low proficient > Early bilingual low proficien | right | 115 | 3.06 | 48 -6 -2 |

| 377 | 2.91 | 56 -24 16 | ||

| Late bilingual high proficient > Early bilingual high proficie | left | 620 | 3.3 | -46 -26 12 |

| Late bilingual high proficient > Early bilingual high proficie | right | 209 | 2.36 | 48 -56 22 |

| Rolandic operculum | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Main effect of L2 proficiency | right | 45 | 6.26 | 52 -24 22 |

| High proficiency > Low proficiency | right | 87 | 2.83 | 48 -22 14 |

| Late bilingual low proficient > Early bilingual low proficien | left | 356 | 3.62 | -52 -4 2 |

| Late bilingual low proficient > Early bilingual low proficien | right | 364 | 2.8 | 54 -22 16 |

| Late bilingual high proficient > Early bilingual high proficie | left | 260 | 3.49 | -46 -26 14 |

| Late bilingual high proficient > Early bilingual high proficie | right | 115 | 2.79 | 46 -20 14 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Early bilingual low proficient > Late bilingual low proficien | right | 143 | 2.48 | 28 40 44 |

| Early bilingual high proficient > Late bilingual high proficie | right | 114 | 2.34 | 40 36 24 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | ||||

| Group comparison | Hemisphere | cluster size (k) | Peak intensity (t) | MNI coordinates |

| Late bilingual low proficient > Early bilingual low proficien | left | 57 | 2.71 | -34 -30 38 |

| Late bilingual high proficient > Early bilingual high proficie | left | 36 | 2.85 | -36 -72 40 |

| 21 | 2.06 | -38 -50 36 |

2.2.2 Bilateral rolandic operculum

There was a main effect of proficiency in the right rolandic operculum where high proficient bilinguals showed increased activity compared to low proficient bilinguals. The reverse comparison of low proficiency relative to high proficiency did not show increased activity. Effects of AoA in this second ANOVA also resembled the pattern of findings reported in the first ANOVA examining the current ROI; namely, late bilinguals showed increased activity in the right and left rolandic operculum relative to early bilinguals of equivalent high or low proficiency level.

2.2.3 Bilateral middle frontal gyrus

There were no main effects of proficiency in either right or left middle frontal gyrus. Similar to the observations noted in the AoA x SES ANOVA, early bilinguals showed increased activity in the right middle frontal gyrus relative to late bilinguals of comparable high or low proficiency level.

2.2.4 Bilateral inferior parietal lobule

There were no main effects of proficiency in either right or left inferior frontal gyrus. Late bilinguals showed increased activity in the left inferior parietal gyrus relative to early bilinguals of comparable high or low proficiency level. Figure 4 contain the fMRI images of the group comparisons in AoA × L2 proficiency ANOVA.

Figure 4.

Region of interest analyses in the bilateral superior temporal gyrus, the bilateral rolandic operculum, the bilateral middle frontal gyrus, and the bilateral inferior parietal lobule in AoA × L2 proficiency ANOVA. Group comparisons in each ROI at the second level of analysis contrast the conditions of English syllables vs. baseline. Comparisons show brain activity between groups of equivalent L2 proficiency level. Red: high L2 proficiency; Cyan: low L2 proficiency. Purple represents the main effect of proficiency collapsed with the contrast of high proficiency vs. low proficiency which showed increased activity in virtually the same coordinates. ROI p-value < 0.05, cluster size k < 20.

Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of age of acquisition, socioeducational status, and L2 proficiency on the neural processing of second language speech sounds. Results from the behavioral data acquired outside the scanner revealed that even though monolinguals were significantly more proficient in English than early and late bilinguals, the groups did not differ in their ability to produce English words that contained the same speech sounds employed in the fMRI task. Bilinguals classified as high or low proficient in English did not differ in the production of L2 words either. These results indicate that even though early and late bilinguals did not have more extensive vocabularies or better comprehension skills in English than monolinguals, both bilingual groups were able to correctly articulate words in the second language. Differences in oral and receptive L2 proficiency may be attritubed to differences in socioeducational backgrounds.

The behavioral findings of speech production outside the scanner partly support our hypotheses as monolinguals and early bilinguals in fact resembled each other in the production of English sounds. Late bilinguals were unexpectedly similar to monolinguals and early bilinguals in the production of L2 words, not showing significant difficulties producing L2 speech. The hypothesis that low proficient bilinguals would have more difficulties producing L2 words than highly proficient bilinguals was not supported by the results. While it is possible that the words employed in the production task did not sufficiently tax the cognitive system thereby impeding the detection of potential perceptual differences between monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals; linking the results of the production task outside the scanner and the perception task in the scanner by employing the same speech sounds was important to interpret the results. Given that perception and production are tightly interrelated (Flege et al., 1997), the behavioral results indicate that all bilingual participants were able to accurately produce L2 words because the speech sounds (/æ/, /ɒ/, /∧/) were properly perceived. That is, all bilinguals had a sufficiently accurate perception of English sounds. Despite comparable perceptual abilities across monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals observed in behavior outside the scanner, the neural mechanisms underlying L2 speech processing differed depending on participants' AoA – especially when equated for SES and L2 proficiency. Also in the behavioral analysis, parental socioeducational differences between the groups did not affect how accurately English words were produced outside the scanner but taking SES into consideration in the fMRI analyses helped increase the robustness of the results by exposing areas of activation with larger clusters and more intensity in the regions investigated.

Region of interest analyses in the left and right superior temporal gyrus, two regions respectively associated with speech perception processes (Binder et al., 2000; Liebenthal, Binder, Spitzer, Possing, & Medler, 2005) and auditory processing of rhythm, stress, and intonation (Geiser, Zaehle, Jancke, & Meyer, 2007), showed that speech sounds elicited activity in different regions within the STG given participants' AoA group and SES. Specific group comparisons showed that monolinguals and late bilinguals more intensely and extensively engaged the bilateral STG relative to early bilinguals of equivalent SES, whereas early bilinguals did not engage the left or right STG relative to monolinguals or late bilinguals of equivalent SES. That is, monolinguals and late bilinguals who were of high or low SES showed more activity in the STG bilaterally relative to early bilinguals of equally high or low SES. This pattern of results was also obtained when early and late bilingual groups of similar proficiency levels were compared. Late bilinguals with a high or low English proficiency level showed increased activity in the STG bilaterally relative to early bilinguals with equivalent proficiency levels. Therefore, the data consistently show that monolinguals and late bilinguals more strongly engage the bilateral STG than early bilinguals when listening to speech sounds. This results suggest that learning one language early in life as a monolingual (either one who continues to be monolingual in adulthood or one who later becomes bilingual) strongly recruits a brain region known to process perceptual auditory information, whereas learning two languages in childhood does not recruit the bilateral STG as intensely.

Contrary to our hypothesis which predicted that monolinguals and early bilinguals would more strongly recruit the bilateral STG relative to late bilinguals, the results indicate that when individuals become experts of one speech sound system in childhood, the STG is recruited to process future new speech sounds. In a parasitic fashion, studies have found that the learning of grammatic and lexico-semantic representations in a second language is supported by the same networks that enable these processes in the first language (Abutalebi, 2008). This also appears to be the case for speech sound learning that occurs after puberty as, in the present study, late bilinguals recruit the same cortical regions for processing L1 and L2 speech sounds.

Late bilinguals, irrespective of SES and proficiency, also showed increased activity in the ROI of the bilateral rolandic operculum relative to monolinguals and early bilinguals. In line with our hypothesis, the recruitment of this region was exclusive to late bilinguals. Early bilinguals and monolinguals did not show activity in the right or left rolandic operculum relative to late bilinguals. Activity in the bilateral rolandic operculum, an area of the ventral premotor cortex, has been reported in neuroimaging studies employing speech perception and speech production tasks (Szenkovits, Peelle, Norris, & Davis, 2012; Wilson et al., 2004). For example, it has been found that listening to speech sounds recruit the left and right rolandic operculum in typically-developing controls and stutterers (Biermann-Ruben, Salmelin, & Schnitzler, 2005). Neuropsychological studies have additionally shown that a lesion to the rolandic operculum impairs patients' ability to internally repeat and maintain verbal information, thus demonstrating the involvement of the rolandic operculum - particularly in the left hemisphere – in subvocal rehearsal (Henson, Burgess, & Frith, 2000; Vallar, Di Betta, & Silveri, 1997). Behavioral studies have noted that subvocal rehearsal mechanisms within the phonological loop of working memory are important for first and L2 acquisition (Baddeley, 2003; G. Brown, 1992). Since continuous subvocal rehearsal is more important for the maintenance of unrelated items (Hashimoto & Sakai, 2002), late bilinguals may be exceedingly recruiting this area to internally rehearse the speech sounds of the L2 which likely remain less interconnected than the sounds of the first language. The results observed in the bilateral rolandic operculum therefore suggest that late bilinguals, regardless of their SES and proficiency level, recruit this pre-motor area to support subvocal rehearsal of L2 sounds learned late in development.

Region of interest analysis in the middle frontal gyrus, an area of the pre-frontal cortex involved in working memory functions including the manipulation and storage of short-term information (Cohen et al., 1997), showed that speech sounds elicited activity in different regions of the bilateral middle frontal gyrus depending on participants' AoA group and SES. The in-depth examination of this interaction showed that early bilinguals increased activity in the right middle frontal gyrus relative to late bilinguals irrespective of SES in response to listening to L2 speech sounds. That is, high or low SES early bilinguals showed more activity relative to late bilinguals of comparable high or low SES. Early bilinguals also showed increased activity in the right middle frontal gyrus when compared to late bilinguals of similar L2 proficiency levels. Therefore, early bilinguals – despite socioeducational or L2 proficiency level – showed increased activity in the right middle frontal gyrus relative to late bilinguals. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, in the middle frontal gyrus, shows peaks of activation in early bilinguals relative to late bilinguals. This region has been reported in the literature of executive functions of task switching in bilinguals (Hernandez, Dapretto, Mazziotta, & Bookheimer, 2001; Wang, Kuhl, Chen, & Dong, 2009) who appear to have superior cognitive control compared to monolinguals due to the environmental demands imposed by managing two languages (Bialystok et al., 2008). Linking previous findings to the results of the present study, it appears that early bilinguals of high or low SES and high or low L2 proficiency level who have extensive experience cognitively maneuvering two languages from an early age strongly recruit prefrontal regions to manipulate speech sound information that is typically processed by regions of the brain involved in auditory perception i.e., STG. In other words, in contrast to the activity evoked by speech sounds in the superior temporal gyrus which monolinguals and late bilinguals more strongly recruit, early bilinguals recruit an area of higher-order executive function and cognitive control to process speech sound information that is fundamentally sensorial. Early bilinguals have a unique linguistic environment that requires the manipulation of speech sounds in early childhood and this appears to trigger the engagement of prefrontal areas to process sound information that is usually processed by temporal brain regions dedicated to auditory perception.

Additionally, early bilinguals showed increased activity in the bilateral middle frontal gyrus relative to monolinguals; however, this activity was only observed when early bilinguals of low SES were compared to monolinguals of equivalent low SES. It has been documented in the literature of socioeconomic status and executive function that individuals from higher SES backgrounds have better attention control, working memory, and fluid processing than individuals from lower SES backgrounds (Lipina et al., 2013). It is thought that the prefrontal cortex, which has a prolonged period of development, is more susceptible to the environmental factors to which children are exposed early in life (Noble & Farah, 2013; Noble, McCandliss, & Farah, 2007). It has also been reported that bilingualism in impoverished environments has a positive effect on overall cognitive function, despite persistent low verbal scores in low SES bilingual children (Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008; Engel de Abreu et al., 2012). In the present study, low SES early bilinguals showed increased activity in the middle frontal gyrus relative to low SES monolinguals. These results indicate that early bilinguals, despite a general socioeducational disadvantage, more strongly recruit areas of executive function which suggests that early bilingualism in the midst of socioeducational difficulties may improve individuals' abilities in higher-order cognition; thus corroborating our hypothesis and the findings of Carlson (2008) and Engel de Abreu, et al (2012). Early bilinguals thus recruit executive regions of the brain to process L2 speech sounds relative to monolinguals and late bilinguals and the extended practice switching between two sound systems may serve to counteract the negative effects of low SES on cognition.

The inferior parietal lobule, an area widely reported in studies with bilinguals (Garbin et al., 2011; Golestani et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009), is known to be part of the fronto-parietal attention control network along with the lateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex (Liu, Slotnick, Serences, & Yantis, 2003; Vincent et al., 2008). The results show that late bilinguals more strongly engage this area relative to early bilinguals and monolinguals of equivalent low SES. Early bilinguals also recruited the inferior parietal lobule bilaterally relative to monolinguals of comparable low SES. Therefore, low SES bilinguals, whether early or late, show stronger activations of the inferior parietal lobule relative to low SES monolinguals. However, only late bilinguals who were either high or low proficient in the second language showed increased activity in the left inferior parietal lobule relative to early bilinguals of equivalent proficiency levels. These results suggest that, like in the middle frontal gyrus, bilingualism may exert a positive effect in the attentional processes of bilinguals of low SES relative to monolinguals of low SES. Even though regions of the prefrontal and parietal cortex compose the fronto-parietal network, the middle frontal gyrus has been primarily associated with working memory processes that include on-line handling of information (Cohen et al., 1997) and the inferior parietal lobule has been mainly associated with selective attention (Behrmann, Geng, & Shomstein, 2004; Posner, Walker, Friedrich, & Rafal, 1984). Since activity in posterior areas of the brain (i.e., inferior parietal lobule) is observed in late bilinguals of either high or low proficiency levels and activity in anterior regions of the brain (i.e., prefrontal cortex/MFG) is observed in early bilinguals of either SES and proficiency levels, it appears that there is a difference in how early and late bilinguals use the attentional network for processing L2 speech sounds. Early bilinguals appear to be engaging working memory prcesses, whereas late bilinguals appear to be relying more on selective attention. Theoretically, selective attention is thought to be a filter that minimizes environmental stimuli for the proper focus of attention on the item(s) of interest (Pugh et al., 1996) while working memory is thought to retain relevant information from the environment for further processing (Koelsch et al., 2009). While selective attention and working memory are not completely independent phenomena, it is possible that late bilinguals reduce the demands of the linguistic environment by selectively attending to the sounds of the second language, whereas early bilinguals absorb all linguistic input from both languages to then mangage, monitor, and choose which language to continue processing. Selective attention may be a more efficient approach for late bilinguals to lessen the phonological intrusions of the first language, whereas manipulating phonological information in working memory may be more efficient approach for early bilinguals to juggle two languages.

Effects of proficiency, contrary to what was hypothesized, were not observed in the ROI's of the inferior partietal lobule and middle frontal gyrus. While working memory and attention processes were respectively observed in early and late bilinguals, activity in these regions was independent of proficiency level. That is, the results presented here do not support the view that successful processing of speech sounds in highly proficient bilignuals increases activity in fronto-parietal regions or that low proficient bilinguals increase activity in these regions due to mental effort. Instead, the results of this study are in line with Wartenburger and colleagues (2003) who showed that the effect of AoA may play a stronger role than proficiency in other aspects of second language learning. An effect of high proficiency relative to low proficiency was observed in the bilateral STG and right rolandic operculum, indicating that highly proficient bilinguals more strongly recruit regions involved in L2 speech perception and subvocal rehearsal. Behavioral studies have found that high proficient bilinguals have improved perception of phonemes that belong to different categories (Archila-Suerte et al., 2011) and the present fMRI results suggest that this improved perception is the result of focused and intense activity in perceptual and articulatory areas. As observed in the results and in support of the hypothesis, there were no main effects of SES in any of the ROI's investigated. However, controlling for SES through direct comparisons between AoA groups made the fMRI results more robust which suggests that SES should be taken into consideration in future bilingual studies.

Taking the behavioral and fMRI findings together, the data suggests that even though early and late bilinguals are similar in their behavioral perception and production of L2 speech sounds, the neural underpinnings of second language speech perception primarily differ depending on the bilingual's AoA, especially when the groups compared are of equivalent SES and L2 proficiency level.

Limitation

Future studies should use more complex stimuli for bilinguals to perceive given that simple stimuli may result in a floor effect that does not allow potential differences between AoA groups to be detected. Future studies could also include independent blocks of visual stimuli, auditory stimuli, a baseline block of silence without visual stimuli, and a mixed block of visual and auditory stimuli. The dissociation of the visual and auditory tasks in some of the blocks could help answer questions of involuntary perceptual control in bilinguals.

Conclusion

Despite similarities in the ability to produce English words between monolinguals, early, and late bilinguals outside the scanner; age of acquisition showed the strongest effect on the neural processing of L2 speech sounds in all the regions of interest examined, especially when the groups were of equivalent socieducational status and L2 proficiency. High proficiency showed some effects in the bilateral superior temporal gyrus and rolandic operculum. In summary, monolinguals and late bilinguals of comparable SES and proficiency levels showed increased activity in the superior temporal gyrus bilaterally relative to early bilinguals, whereas early bilinguals showed increased activity in the right middle frontal gyrus relative to late bilinguals of equivalent SES and L2 proficiency level. Early bilinguals also showed increased activity in the middle frontal gyrus bilaterally relative to monolinguals of equivalent low SES. Additionally, late bilinguals – irrespective of SES or proficiency – showed increased activity in the bilateral rolandic operculum, while low SES bilinguals (both early or late) showed activity in the inferior parietal lobule. Late bilinguals of both proficiency levels (low and high) also showed increased activity in the left inferior parietal lobule. The results suggest that early acquisition of one language recruits expected temporal regions involved in perceptual processing, whereas early acquisition of two languages increases the engagement of prefrontal regions involved in working memory to process L2 speech sounds. Furthermore, the results suggest that bilingualism can serve to counteract the negative effects of low socioeducational environments on cognition and that late bilinguals may be using more selective attention (posterior areas) than early bilinguals to process L2 speech sounds. Therefore, AoA appears to play an important role in L2 speech processing that is tied to SES and proficiency level in the second language.

Statement of significance.

No studies have investigated the role of multiple within-subject variables on the neural processing of L2 speech sounds. Investigating the neural processes underlying L2 speech perception is a preliminary step that will help generate future research to understand how bilingual perception affects other linguistic skills.

Highlights.

AoA showed the strongest effect on the neural processing of L2 speech sounds

Monolinguals and late bilinguals activated the STG relative to early bilinguals

Early bilinguals activated the MFG relative to monolinguals and late bilinguals

Late bilinguals activated the Rolandic operculum relative to the other two groups

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Institute for Biomedical Imaging Science (IBIS) and grant 1R21HD059103-01 from the National Institute of Health. We thank Dr. Tom Zeffiro for his guidance with data analysis and all the research assistants for their help with data collection. We would also like to thank graduate students Kaylin Bradley, Kelly Vaughn, and Madeleine Warner for proofreading previous versions and the current manuscript to ensure legibility and correctness in English usage.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Pilar Archila-Suerte, University of Houston.

Jason Zevin, Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 1300 York Ave. Box 140, NY, NY 10065.

Arturo E. Hernandez, University of Houston

References

- Abutalebi J. Neural aspects of second language representation and language control. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2008;128(3):466–478. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albareda-Castellot B, Pons F, Sebastián-Gallés N. The acquisition of phonetic categories in bilingual infants: new data from an anticipatory eye movement paradigm. Developmental Science. 2011;14(2):395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga-Garcia C, Mora JC. Assessing the effects of phonetic training on L2 sound perception and production. In: Watkins AMA, Rauber AS, Baptista BO, editors. Recent Research in Second Language Phonetics/Phonology: Perception and Production. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2009. pp. 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Archila-Suerte P, Zevin J, Bunta F, Hernandez AE. Age of Acquisition and Proficiency in a Second Language Independently Influence the Perception of Non-native Speech. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2011;15(1):190–201. doi: 10.1017/S1366728911000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archila-Suerte P, Zevin J, Ramos A, Hernandez A. The Neural Basis of Non-Native Speech Perception in Bilingual Children. NeuroImage. 2013;67:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. Working memory and language: an overview. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2003;36(3):189–208. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(03)00019-4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann M, Geng J, Shomstein S. Parietal cortex and attention. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2004;14:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson RR, Whalen DH, Richardson M, Swainson B, Clark VP, Lai S, Liberman AM. Parametrically dissociating speech and nonspeech perception in the brain using fMRI. Brain Lang. 2001;78(3):364–396. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best C, McRoberts GW. Infant perception of non-native consonant contrasts that adults assimilate in different ways. Lang Speech. 2003;46(Pt 2-3):183–216. doi: 10.1177/00238309030460020701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]