Abstract

AIM

To investigate the effect of the overexpression of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) on homing of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in vitro and therapeutic effects of diabetic retinopathy (DR) in vivo.

METHODS

MSCs were infected by lentivirus constructed with CXCR4. The expression of CXCR4 was examined by immunofluorescence, Western blot, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction. CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs were cultured in vitro to evaluate their chemotaxis, migration, and apoptotic activities. CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs were intravitreally injected to observe and compare their effects in a mouse model of DR. The histological structure of DR in rats was inspected by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The expression of rhodopsin, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α was examined by Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses.

RESULTS

The transduction of MSCs by lentivirus was effective, and the transduced MSCs had high expression levels of CXCR4 gene and protein. Improved migration activities were observed in CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs. Further, reduced retinal damage, upregulation of rhodopsin and NSE protein, and downregulation of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α were observed in CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs in vivo.

CONCLUSION

The homing of MSCs can be enhanced by upregulating CXCR4 levels, possibly improving histological structures of DR. CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs can be a novel strategy for treating DR.

Keywords: chemokine receptor type 4, diabetic retinopathy, mesenchymal stem cells, transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is thought to be a microcirculatory disease in the retina caused by the deleterious metabolic effects of hyperglycemia[1]. The early pathogenesis of DR may be due to chronic degeneration of retinal nerve tissue, including reactive glial cell proliferation and neuronal apoptosis. These factors lead to increased microvascular permeability and progressive microvascular occlusion, causing tissue hypoxia/ischemia and eventually triggering retinal neovascularization[2]. Endothelial dysfunction is the earliest pathological change in the course of DR formation. Stem cell therapy has become one of the most promising therapeutic strategies for DR with the development of modern medical technology in the field of gene and stem cell therapy[3].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) originate from the embryonic mesoderm during embryonic development. MSCs are distributed in a variety of cellular and somatic tissues, but they are present only in bone marrow and connective tissue in adults[4]. A previous study reported that MSCs could promote the regeneration of neural pathways in endogenous endothelial progenitor cells[5]. Another study showed that MSC transplantation improved DR through direct peripheral nerve angiogenesis, neurotrophic effects, and restoration of surviving retinal ganglion cells (RGCs)[6]. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) was identified as a chemoattractant for MSCs. SDF-1 guides the migration of MSCs to the site of injury with the help of its C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4)[7]. Similar studies showed that the overexpression of MSCs with CXCR4 could improve the density of MSCs at the injury site, and CXCR4 acted as an important factor related to migration that improved the therapeutic effects of MSCs[8]. All these studies highlighted the importance of cell migration in stem cell therapy.

Taking into account the significance of SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in the homing of MSCs and the potential of MSCs in DR therapy, this study investigated the novel concept of overexpressing CXCR4 in MSCs and the effect of this approach on the migratory capacities of MSCs isolated from rats. Further, intravitreal transplantation of CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs in rats with DR was explored, resulting in a long-term preservation of retinal function and significantly delaying the progression of DR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation, Cultivation, and Characterization of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

The study was approved by the Tianjin Medical University Medical Ethics Committee and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, including current revisions, and the good clinical practice guidelines. The procedures followed were in accordance with institutional guidelines. MSCs from bone marrow of healthy rats were isolated as previously described[9]. Briefly, the rats were decapitated under anesthesia and then soaked in 75% ethanol for 15min. The bone marrow cavity was repeatedly washed with 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 4°C, pH 7.3) after clipping the femur and tibia. The samples were centrifuged using ficoll-hypaque to isolate mononuclear cells (MNCs) for MSC culture. Isolated MNCs were re-suspended and cultured in low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (LG-DMEM) containing 20% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 ng/mL epidermal growth factor at 37°C in the presence of 5% (v/v) CO2. After 5d, nonadherent cells were discarded and adherent cells were further cultured with two changes of medium per week. The cultured MSCs were examined by immunofluorescence.

Lentiviral Vectors and Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transduction

The open reading frame of rat CXCR4 was amplified from brain cDNA and ligated in-frame into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA). The variant of CXCR4 was transformed into competent Escherichia coli cells, and then the cells were inoculated on an Amp-resistant plate. Positive clones were connected with the pCDH-CMV-CXCR4-EF1-copGFP vector, which contained a lentiviral vector carrying the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene, to construct the CXCR4-GFP co-expression vector. The pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP vectors expressed only GFP as the control.

The MSCs were inoculated with pCDH-CMV-CXCR4-EF1-copGFP to yield CXCR4-secreting MSCs (CXCR4-MSCs) or with pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP to produce MSCs for control experiments (GFP-MSCs). Single cells with the highest expression levels of the reporter gene were plated into 96-well plates by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to establish clonally derived GFP-MSCs and CXCR4-MSCs. The expression of CXCR4 gene in CXCR4-MSCs was examined by immunofluorescence, Western blot, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Functional Assays of C-X-C Chemokine Receptor Type 4-secreting Mesenchymal Stem Cells

CXCR4-MSCs were digested with 0.25% trypsin and then cultured in serum-free medium in 96-well culture plates (200 µL/well). After culturing for 24h, endothelial progenitor cells were treated with 10 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (5 g/L; Fluka, USA) and incubated for another 4h. The supernatant was then discarded by aspiration, and the CXCR4-MSC samples were shaken with 200 µL of dimethylsulfoxide for 10min before the optical density value was measured at 490 nm.

A migration assay was performed using a modified Boyden chamber. After 7d in culture, 3×104 CXCR4-MSCs were placed in the upper well of the modified Boyden chamber (Corning Costar, USA) for 12h. The lower well of the chamber contained LG-DMEM and recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor (50 ng/mL; Sigma, USA). The nuclei of cells that migrated into the lower chamber were stained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and counted manually in five random microscopic fields (200×) from each well. Each experiment of functional assays was repeated eight times.

The apoptotic activities of CXCR4-MSCs were examined by flow cytometry. The cells were washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and then labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-rat Annexin V monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson, USA). The data were analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, USA).

Model Preparation

From the Tianjin Medical University of China, we purchased male Sprague-Dawley rats which aged 12wk. The rats were injected with a single dose of streptozotocin (STZ) into the tail vein (50 mg/kg body weight in 5 mmol/L, pH 4.5, citrate buffer) after anesthetized with ketamine/xylocaine for inducing diabetes mellitus type 1. Before initiating the feeding regimen, the rats were allowed to recover for 4d. To verify diabetes mellitus type 1, we used an Accu-check Sensor Analyzer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) to measure the levels of blood glucose. To ensure that hyperglycemia was maintained and to treat any extreme glycemic levels with insulin, we monitored the blood glucose during the study. The rats with blood glucose levels exceeding only 300 mg/dL were considered hyperglycemic and included in the study of the STZ-treated rats[6].

The rats were randomly divided into four groups: normal control (n=14, Group A), diabetic control (n=14, Group B), GFP-MSC-treated (n=14, Group C), and CXCR4-MSC-treated diabetic (n=14, Group D) groups. GFP-MSCs and CXCR4-MSCs were intravitreally transplanted into rats with diabetes induced for 4mo with STZ. The rats were subjected to xylazine (20 mg/kg) and ketamine (75 mg/kg) intraperitoneal anesthesia. We performed cell transplantation under a surgical microscope. After that, 0.2×106 cells in 2 µL were transplanted intravitreally using a disposable insulin syringe [0.1 mL volume, 0.30 mm (30G)×8 mm] (BD Micro-Fine Plus, Becton Dickinson)[6]. The syringe needle was introduced with its opening facing the vitreous and close to the retina. The morphological changes in the retina were observed 4wk after transplantation.

Histological Analysis

Four rats from each group were sacrificed at each time point 4wk after transplantation, and their eyes were immediately removed. After that the eyes were immersed in a cold fixative of 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer. The eyes were left in the fixative for 24h after the corneas were removed. We removed the lens after dehydration them with a graded series of increasing ethanol concentrations. After embeding the eyecups in paraffin, we used routine hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining to stain the paraffin-embedded sections, and used a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, USA) equipped with a digital camera to examine the staining.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Four rats from each group were sacrificed at each time point 4wk after transplantation. The eyes were removed and fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution. Serial 4-µm paraffin sections of the retina were used to stain for polyclonal rabbit anti-rat rhodopsin/neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and interleukin (IL)-6/tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibody (Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China). Controls were obtained by replacing the primary antibody with PBS. The staining was visualized by reaction with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co., USA). Immunostaining for rhodopsin/NSE and IL-6/TNF-α was quantified by calculating the proportion of the area occupied by brown staining in the retinal tissue using a computer imaging analysis system.

Western Blot Analysis

Six rats from each group were deeply anesthetized 4wk after transplantation. Western blot analysis was performed using standard methods. Briefly, retinas were dissected carefully from the rat eyes. The protein concentration in the tissue lysates was measured using a protein assay kit (Bradford Protein Assay; Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Proteins were transferred electrophoretically onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, MA, USA), and the membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk and incubated with rhodopsin/NSE and IL-6/TNF-α primary antibodies (Boster Biological Technology) at 4°C overnight. After that, we incubated the membranes with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at room temperature for 2h and using the ChemiDoc MP System (Bio-Rad) to visualize the rezults. For statistical analysis, the protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

The data were presented as mean±standard error of mean. They were compared by one-way analysis of variance. A P value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed with a statistical software package (SPSS 13.0, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Isolation, Cultivation, and Characterization of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

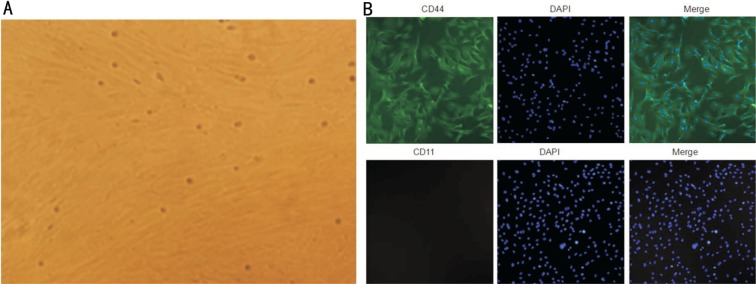

MSCs appeared as a monolayer of large, flat cells. The morphology of the cells was uniform with a spindle or spiral shape or racial arrangement (Figure 1A). Immunofluorescence studies indicated that MSCs exhibited a characteristic immunophenotype. CD44 was highly expressed, but CD11 were weakly expressed (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Morphologic and immunophenotypic characterization of MSCs.

A: Morphology at a 40× magnification; B: Immunofluorescence studies indicated that the MSCs exhibited a characteristic immunophenotype. CD44 was highly expressed, but CD11 were weakly expressed.

CXCR4-MSC transduction and functional assays of CXCR4-MSCs

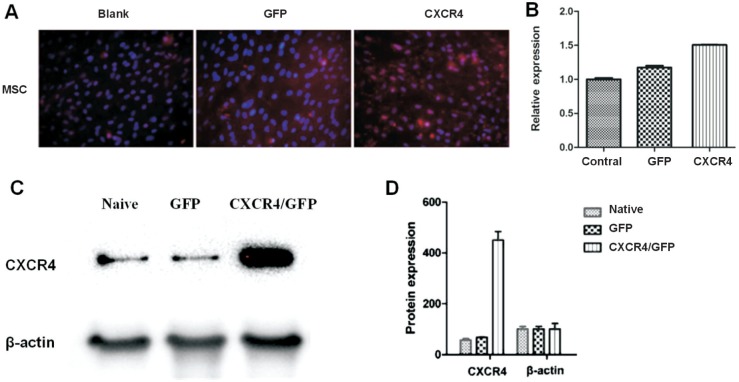

The transduction of MSCs by lentivirus was effective, and the immunohistochemical analysis showed the positive staining of CXCR4 in CXCR4-transfected MSCs compared with nontransfected MSCs (Figure 2A). The qPCR analysis showed that the mRNA level of CXCR4 increased in CXCR4-transfected MSCs compared with nontransfected MSCs (P<0.05; Figure 2B). Also, the protein level of CXCR4 significantly increased in CXCR4-transfected MSCs compared with nontransfected MSCs (P<0.05; Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2. Transduction of CXCR4-MSCs.

A: The immunohistochemical analysis showed the positive staining of CXCR4 in CXCR4-transfected MSCs; B: The qPCR analysis showed that the mRNA level of CXCR4 increased in CXCR4-transfected MSCs; C, D: The protein level of CXCR4 significantly increased in CXCR4-transfected MSCs.

The proliferative activity of CXCR4-transfected MSCs did not significantly improve compared with nontransfected MSCs (P>0.05). Interestingly, the migration activity of CXCR4-transfected MSCs significantly improved compared with nontransfected MSCs (P<0.05). The ratio of Annexin V-positive cells to the total number of cells from CXCR4-transfected MSCs and nontransfected MSCs was 8.23% and 8.63%, respectively, as identified using the flow cytometric analysis, suggesting that the apoptotic activity of CXCR4-transfected MSCs did not significantly decrease compared with nontransfected MSCs (P<0.05).

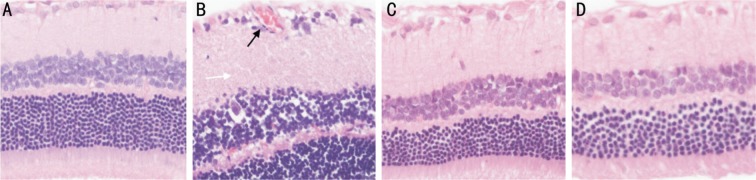

Light Microscopic Analysis

In Group A, the structure of the retina was continuous, and its capillary structure was normal (Figure 3A). The tissue layers of the retina developed telangiectatic vessels in the inner layer, and many ganglion cells developed vacuolar degeneration in the inner nuclear layer in Group B (Figure 3B). In Groups C and D, treatment with GFP-MSCs and CXCR4-MSCs attenuated the retinal vascular dysfunction, and the tissue layers of the retina were gradually arranged regularly (Figure 3C, 3D).

Figure 3. Retinal HE staining.

A: The structure of the retina was continuous and its capillary structure was normal in Group A; B: The tissue layers of the retina were edematous, and the retina developed telangiectatic vessels (black arrow) in Group B; C, D: Treatment with GFP-MSCs and CXCR4-MSCs attenuated the retinal vascular dysfunction, and the tissue layers of the retina were gradually arranged regularly in Groups C and D. HE×200.

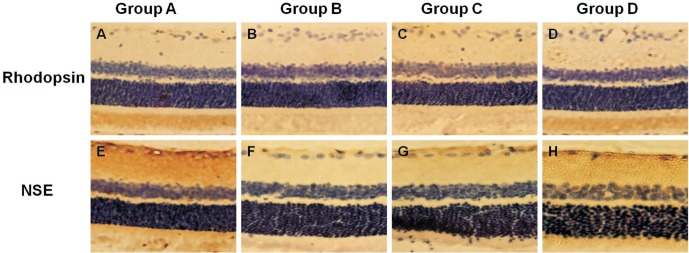

Rhodopsin/Neuron-specific Enolase and Interleukin-6/Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Assay

Rhodopsin/NSE is involved in the formation, plasticity, and survival of retinal photoreceptor cells in the retina. This can help evaluate the degree of visual function in DR. rhodopsin/NSE-positive cells were found in the ganglion cell and nerve fiber layers in the control group (1.81% and 1.65%; Figure 4A, 4E). Four weeks following cell transplantation, the number of rhodopsin/NSE-positive cells in the ganglion cell and external nuclear layers decreased in Group B (0.39% and 0.31%, P<0.05; Figure 4B, 4F). In contrast, the numbers of rhodopsin/NSE-positive cells in Group C (1.03% and 0.71%; Figure 4C, 4G) and Group D (1.33% and 1.25%; Figure 4D, 4H) increased compared with Group B (P<0.05).

Figure 4. Expression of rhodopsin/NSE in the retina.

A, E: Rhodopsin/NSE-positive cells were found in the ganglion cell and nerve fiber layers in Group A; B, F: The number of rhodopsin/NSE-positive cells in the ganglion cell and external nuclear layers decreased in Group B; C, G; D, H: A marked increase in rhodopsin/NSE-positive cells in Groups C and D; the number increased especially in Group D compared with Group C. Immunohistochemical staining ×200.

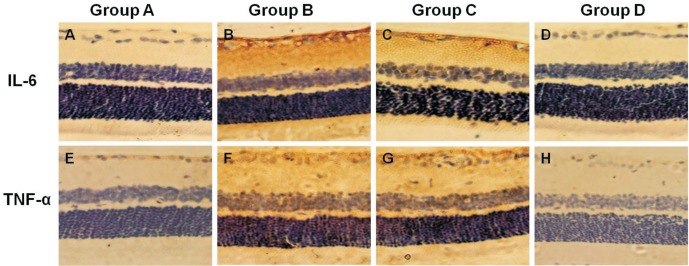

Immunohistochemical staining for the expression of IL-6/TNF-α in Group A was positive (0.32% and 0.37%; Figure 5A, 5E). The number of Thy-1-positive cells gradually increased mainly in the ganglion cell layer in Group B (1.10% and 1.63%, P<0.05; Figure 5B, 5F). However, the number of IL-6/TNF-α-positive cells decreased in Group C (0.95% and 1.24%; Figure 5C, 5G) and Group D (0.56% and 0.33%; Figure 5D, 5H) compared with Group B. The number of IL-6/TNF-α-positive cells decreased especially in Group D compared with Group C (P<0.05).

Figure 5. Expression of IL-6/TNF-α in the retina.

A, E: IL-6/TNF-α positive cells were found in the ganglion cell and nerve fiber layers in Group A; B, F: The number of IL-6/TNF-α-positive cells in the ganglion cell layer increased in Group B; C, G; D, H: A marked increase in IL-6/TNF-α-positive cells was observed in Groups C and D; the number decreased especially in Group D compared with Group C. Immunohistochemical staining ×200.

Western Blot Analysis

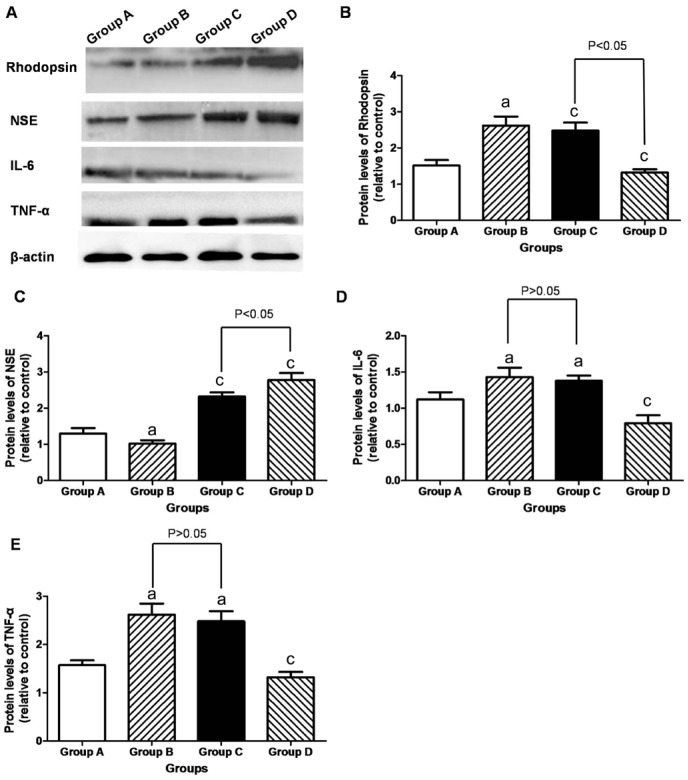

The retinal rhodopsin/NSE protein in Group B (1.23±0.09 and 1.02±0.11) was lower than that in Group A (1.52±0.15 and 1.30±0.12) (P<0.05). In contrast, the retinal rhodopsin/NSE protein increased in Group C (2.02±0.09 and 2.32±0.05) and Group D (2.29±0.11 and 2.78±0.19). Especially, the retinal rhodopsin/NSE protein was higher in Group D than in Group C (P<0.05; Figure 6).

Figure 6. Western blot analysis in the retina.

A: Representative Western blot was shown; B-E: The retinal rhodopsin/NSE protein in Group B was lower than that in Group A, but increased in Groups C and D. It was higher in Group D than in Group C (P<0.05). The retinal IL-6/TNF-α protein was higher in Group B than in Group A (P<0.05), but its decreased in Group D (P<0.05). aP<0.05 vs Group A; cP<0.05 vs Group B.

The retinal IL-6/TNF-α protein in Group B (1.43±0.13 and 2.62±0.25) was higher than that in Group A (1.12±0.10 and 1.57±0.19) (P<0.05). In contrast, the retinal IL-6/TNF-α protein decreased in Group D (0.79±0.15 and 1.32±0.09) than that in Group B (P<0.05). Especially, the retinal IL-6/TNF-α protein in Group C (1.32±0.23 and 2.48±0.31) did not differ from that in Group B (P>0.05; Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that the homing of MSCs could be enhanced by upregulating CXCR4 levels, possibly improving histological structures of DR. CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs could be a novel strategy for treating DR.

Recombinant lentivirus vectors have gradually gained the interest of researchers. However, lentivirus vector-mediated MSCs transfected with CXCR4 have not been reported. In this study, the cultured MSCs were transfected with GFP and lentiviral vectors, and the results were consistent with previous findings. Immunocytochemical analysis, qPCR, and Western blot analysis were performed to observe that the transduction of MSCs with CXCR4 by lentivirus was effective. The lentivirus-mediated CXCR4 gene was transfected into MSCs. It was found that cell proliferation was not inhibited, and the cells were capable of stably expressing CXCR4. The transfection efficiency significantly increased with prolonged infection time.

CXCR4 was therefore crucial in stem cell migration in Transwell assays. The retinal structure and function deteriorated due to hyperglycemia, resulting in DR. Also, MSCs derived from rats with DR had impaired migration toward chemoattractants[10]. SDF-1 was demonstrated to recruit more MSCs to a retinal injury site and encourage retinal vascular repair[11]. The functional assays of CXCR4-MSCs showed no change in chemotaxis and apoptotic activities of CXCR4-MSCs.

Nowadays, MSCs have become a promising source for stem cell-based regenerative therapy. A previous study reported that MSC transplantation improved DR through direct peripheral nerve angiogenesis, neurotrophic effects, and restoration of surviving RGCs[6]. In the present study, morphological observation, immunocytochemical analysis, and Western blot were performed to observe the potential functional changes in the retina after MSC therapy. CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs showed reduced retinal damage, upregulation of rhodopsin and NSE, and downregulation of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. The main recovery mechanisms of MSCs are mediated by secretory factors, and thought to be paracrine effects[12]. After the transplantation of MSCs into the vitreous, the cells could not be maintained for a long time but beneficial effects were observed. MSCs could display trophic influences, suggesting that CXCR4-MSCs might be used in cell-based therapy for vascular injuries of DR[13].

SDF-1α and CXCR4 axis is important to signaling pathways in neovascularization including embryonic vasculogenesis[14]. Recently, the beneficial effects of SDF-1α on angiogenesis in myocardial infarction[15] and spinal cord regeneration were reported[16], suggesting that increasing SDF-1 levels enhanced stem cell recruitment at the site of injury. Stem cell migration toward SDF-1 reduced after DR induction. The reduced migration of MSCs might be due to an increased extracellular matrix deposition, followed by greater surface adherence[17]. Consistent with previous observations, the present study demonstrated that CXCR4-MSCs had significantly increased expression of rhodopsin/NSE in rats with DR, suggesting that CXCR4-MSC could regulate retinal pericytes and endothelial cells and might improve the formation and plasticity of retinal photoreceptor cells.

Long-term hyperglycemia exposure has been demonstrated to induce oxidative stress and increase production of cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, which are believed to contribute to the destruction of endothelial integrity in patients with DR[18]. Increased levels of these inflammatory cytokines are also due to a reduction in vascular repair[19]. In the present study, Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis were performed to evaluate the expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in rats with DR after CXCR4-MSC treatment. CXCR4-overexpressing MSCs showed retinal damage and downregulation of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. Whether CXCR4-MSCs directly regulate this differential expression of inflammatory cytokines, which is critical for vascular remodeling, needs to be investigated. One potential mechanism is that CXCR4-MSCs secrete several trophic factors at the site of injury to correct this aberrant pattern of expression of vascular inflammatory cytokines[20]. Recent studies have found that several types of cell, including MSCs, can affect the adjacent cells by the release of exosomes[21]. Moreover, the MSCs-derived exosomes seem to reduce the leakage of the vessel in a model of DR, whereas RPE-derived exosomes do not prevent the leakage of new blood vessels[22]. Consecutively, another group showed that MSCs-derived exosomes could inhibit the neovascularization by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappa B signaling[23]. These results suggested that transplantation of MSC-derived exosomes might act as a putative therapeutic tool to protect the retina.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that CXCR4-MSCs exerted a therapeutic effect by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory cytokines and significantly reduced the progression of DR. These results suggested that the transplantation of CXCR4-MSCs could be a novel strategy for treating DR. Future studies should examine the safety of this procedure in large animal models that closely mimic the human eye.

Acknowledgments

Foundations: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81700846); Tianjin Science and Technology Project of China (No.13ZCZDSY01500).

Conflicts of Interest: Wang J, None; Zhang W, None; He GH, None; Wu B, None; Chen S, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hu W, Wang R, Li J, Zhang J, Wang W. Association of irisin concentrations with the presence of diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2016;53(Pt 1):67–74. doi: 10.1177/0004563215582072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foureaux G, Nogueira BS, Coutinho DC, Raizada MK, Nogueira JC, Ferreira AJ. Activation of endogenous angiotensin converting enzyme 2 prevents early injuries induced by hyperglycemia in rat retina. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015;48(12):1109–1114. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20154583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterniti I, Di Paola R, Campolo M, Siracusa R, Cordaro M, Bruschetta G, Tremolada G, Maestroni A, Bandello F, Esposito E, Zerbini G, Cuzzocrea S. Palmitoylethanolamide treatment reduces retinal inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;769:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang X, Ding Y, Zhang Y, Tse HF, Lian Q. Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: current status and perspectives. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(9):1045–1059. doi: 10.3727/096368913X667709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Zhang W, Wang JM, Duan HT, Kong JH, Wang YX, Dong M, Bi X, Song J. Differentiation of isolated human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells into neural stem cells. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(1):41–47. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2016.01.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W, Wang Y, Kong J, Dong M, Duan H, Chen S. Therapeutic efficacy of neural stem cells originating from umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):408. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asfour I, Afify H, Elkourashy S, Ayoub M, Kamal G, Gamal M, Elgohary G. CXCR4 (CD184) expression on stem cell harvest and CD34+ cells post-transplant. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2017;10(2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bang OY, Moon GJ, Kim DH, Lee JH, Kim S, Son JP, Cho YH, Chang WH, Kim YH, STARTING-2 trial investigators Stroke induces mesenchymal stem cell migration to infarcted brain areas via CXCR4 and C-Met signaling. Transl Stroke Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12975-017-0538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Yan H. Dysfunction of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in type 1 diabetic rats with diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(4):1123–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He J, Wang Y, Lu X, Zhu B, Pei X, Wu J, Zhao W. Micro-vesicles derived from bone marrow stem cells protect the kidney both in vivo and in vitro by microRNA-dependent repairing. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20(9):591–600. doi: 10.1111/nep.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas KW, Gilleece M, Hayden P, et al. UK consensus statement on the use of plerixafor to facilitate autologous peripheral blood stem cell collection to support high-dose chemoradiotherapy for patients with malignancy. J Clin Apher. 2018;33(1):46–59. doi: 10.1002/jca.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Emond ZM, Flynn ME, Swaminathan S, Kibbe MR. Microparticle levels after arterial injury and NO therapy in diabetes. J Surg Res. 2016;200(2):722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravina GL, Mancini A, Colapietro A, Vitale F, Vetuschi A, Pompili S, Rossi G, Marampon F, Richardson PJ, Patient L, Patient L, Burbidge S, Festuccia C. The novel CXCR4 antagonist, PRX177561, reduces tumor cell proliferation and accelerates cancer stem cell differentiation in glioblastoma preclinical models. Tumour Biol. 2017;39(6):1010428317695528. doi: 10.1177/1010428317695528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalimuthu S, Oh JM, Gangadaran P, Zhu L, Lee HW, Rajendran RL, Baek SH, Jeon YH, Jeong SY, Lee SW, Lee J, Ahn BC. In vivo tracking of chemokine receptor CXCR4-engineered mesenchymal stem cell migration by optical molecular imaging. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:8085637. doi: 10.1155/2017/8085637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsou LK, Huang YH, Song JS, Ke YY, Huang JK, Shia KS. Harnessing CXCR4 antagonists in stem cell mobilization, HIV infection, ischemic diseases, and oncology. Med Res Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1002/med.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Dykstra B, Spencer JA, Kenney LL, Greiner DL, Shultz LD, Brehm MA, Lin CP, Sackstein R, Rossi DJ. mRNA-mediated glycoengineering ameliorates deficient homing of human stem cell-derived hematopoietic progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(6):2433–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI92030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahin Ersoy G, Zolbin MM, Cosar E, Moridi I, Mamillapalli R, Taylor HS. CXCL12 promotes stem cell recruitment and uterine repair after injury in Asherman's syndrome. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2017;4:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madonna R, Giovannelli G, Confalone P, Renna FV, Geng YJ, De Caterina R. High glucose-induced hyperosmolarity contributes to COX-2 expression and angiogenesis: implications for diabetic retinopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:18. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0342-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung SH, Kim YS, Lee YR, Kim JS. High glucose-induced changes in hyaloid-retinal vessels during early ocular development of zebrafish: a short-term animal model of diabetic retinopathy. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(1):15–26. doi: 10.1111/bph.13279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Xia S, Fang H, Pan J, Jia Y, Deng G. VEGF treatment promotes bone marrow-derived CXCR4+ mesenchymal stromal stem cell differentiation into vessel endothelial cells. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13(2):449–454. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwan KM. Coming into focus: the role of extracellular matrix in vertebrate optic cup morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2014;243(10):1242–1248. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips MJ, Perez ET, Martin JM, Reshel ST, Wallace KA, Capowski EE, Singh R, Wright LS, Clark EM, Barney PM, Stewart R, Dickerson SJ, Miller MJ, Percin EF, Thomson JA, Gamm DM. Modeling human retinal development with patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells reveals multiple roles for visual system homeobox 2. Stem cells. 2014;32(6):1480–1492. doi: 10.1002/stem.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atienzar-Aroca S, Flores-Bellver M, Serrano-Heras G, Martinez-Gil N, Barcia JM, Aparicio S, Perez-Cremades D, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Diaz-Llopis M, Romero FJ, Sancho-Pelluz J. Oxidative stress in retinal pigment epithelium cells increases exosome secretion and promotes angiogenesis in endothelial cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20(8):1457–1466. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]