Abstract

Background

The preservation of the economic livelihood of tobacco farmers is a common argument used to oppose tobacco control measures. However, little empirical evidence exists about these livelihoods. We seek to evaluate the economic livelihoods of individual tobacco farmers in Malawi, including how much money they earn from selling tobacco, and the costs they incur to produce the crop, including labour inputs. We also evaluate farmers’ decisions to contract directly with firms that buy their crops.

Methods

We designed and implemented an economic survey of 685 tobacco farmers, including both independent and contract farmers, across the six main tobacco-growing districts. We augmented the survey with focus group discussions with sub-sets of respondents from each region to refine our inquiries.

Results

Contract farmers cultivating tobacco in Malawi as their main economic livelihoods are typically operating at margins that place their households well below national poverty thresholds, while independent farmers are typically operating at a loss. Even when labour is excluded from the calculation of income less costs, farmers’ gross margins place most households in the bottom income decile of the overall population. Tobacco farmers appear to contract principally as a means to obtain credit, which is consistently reported to be difficult to obtain.

Conclusions

The tobacco industry narrative that tobacco farming is a lucrative economic endeavour for smallholder farmers is demonstrably inaccurate in the context of Malawi. From the perspective of these farmers, tobacco farming is an economically challenging livelihood for most.

Keywords: Tobacco, Economics, Tobacco Farmers, Tobacco Industry

Introduction

The arguments against tobacco control are often deeply rooted in the purported economic benefits (1–4). Tobacco farmers are often caught in the middle of efforts to control tobacco products and thus reduce consumption, and tobacco industry interests that work vigorously to maintain their economic profitability (3). These interests – which include cigarette manufacturers, leaf buyers, agricultural lobby organizations, and industry-funded non-governmental organizations, among others – often claim that tobacco control will result in economic hardship for farmers who rely on this crop (1,3). It is common for governments of tobacco-producing countries to use farmers’ livelihoods to resist tobacco control, exemplified in recent informal challenges to novel tobacco control measures at the World Trade Organization (5–9). However, the empirical evidence to support such opposition remains scarce.

Our research involves a systematic examination of the profits of smallholder farmers in Malawi using a nationally representative survey. This study builds on earlier research (10–13) that examines the profitability of tobacco farming, finding that it was typically among the more profitable – though not lucrative – crops in Malawi owing largely to the industry’s well developed value chains. Our study, however, also draws from a couple of country case studies that consider the systematic incorporation of labour costs into these analyses (14,15). We also examine the closely related economic dynamics around contract farming. This study contributes to the empirical evidence in two ways. Our first analysis identifies tobacco farmer profits after accounting for the different costs of production, including labour. The second analysis examines the factors that differentiate independent and contract farmers, in part to explain any differences in economic livelihoods between these groups.

The Context of Tobacco Farming in Malawi

Malawi is the top global producer of burley tobacco and one of the top ten global producers of tobacco leaf. Tobacco is the country’s main cash crop, reported to contribute to between sixty and seventy percent of export earnings (12,16). Tobacco leaf cultivation is reported to employ an estimated 780,000 people, approximately 468,000 of them being smallholder farmers (17). Malawi has also been a prominent opponent of tobacco control globally, including challenges to novel tobacco control in international economic fora (18), and resistance to the development of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) (19). Incidentally, Malawi is one of a small number of countries that is not a Party to the WHO FCTC.

Tobacco farmers in Malawi are categorized into two main groups: smallholder farmers and estate farmers. Before political and economic reforms in the early 1990s, the government restricted smallholder tobacco growing. But market liberalization allowed the private sector to be involved in marketing and purchasing. In 2005, the Tobacco Association of Malawi (TAMA), a non-profit private association of tobacco growers, introduced burley tobacco contract marketing (13). Contract farming involves legal arrangements between farmers and tobacco leaf-buying companies whereby farmers sell exclusively to the company. In return, the tobacco leaf companies provide the farmers with agricultural inputs (e.g. fertilizers, seeds) on credit, extension services (which are no longer provided by government) and sometimes, cash loans. Under significant pressure from leaf-buying firms and transnational tobacco corporations, the burley tobacco contract marketing was approved by the government and fully adopted in 2012 as the Integrated Production System (IPS). The majority of tobacco leaf produced in Malawi is now sold through contract farming (20). Many farmers have agreed to contractual arrangements because it is difficult to access other bank and government credit facilities (20). Finally, tobacco farmers are assured a market (contracting leaf company) for their tobacco leaf at the end of the growing season, though the pricing is not specified in the contract. Despite the fact that IPS was implemented in part as a response to leaf buyers operating as a cartel and depressing the price of leaf (13), the system continues to perpetuate monopsonistic market conditions, giving tobacco leaf companies extensive control over tobacco leaf grading and pricing (21). Evidence from some focus group participants (discussed below) suggests that independent farmers may be disadvantaged by the IPS system wherein their tobacco may receive a lower grade, a lower price and may be purchased only after buyers have given preference to contract farmers.

Methods

A survey of smallholder tobacco farmers was conducted in November and December 2014 in six major tobacco-growing districts of Malawi. The six districts were purposively sampled as the leading tobacco producing districts, based on nationally representative production data from the 2010 Integrated Household Survey. Production data from the Ministry of Agriculture also confirmed the selection of the six districts. The second stratum was a purposive sample of two traditional authorities (TAs), the key sub-district distinction in Malawi, within each district where tobacco is the major crop. The third stratum was a random sample of three group villages (communities) from a list of all of the villages growing tobacco as a major crop in each TA. Within each selected group village, a random sample of 20 farmers was drawn from a complete list of tobacco farmers for 2013–14 provided with the assistance of the group village head (the traditional leader) and the local government agricultural extension worker. The data collection team was comprised of eight interviewers, one research supervisor and one principal investigator. The survey questionnaire was divided into 9 sections: household characteristics; livelihood, income and assets; land ownership and crop production; tobacco production generally; tobacco production under the IPS; tobacco marketing; farmer debt and credit; household food security; and the future of tobacco production. The questionnaire was administered to 685 tobacco farmers. The data were entered in SPSS (Version 20.0) and analyzed using SPSS and STATA (Version 12.1) statistical packages. All activities for this research were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Morehouse School of Medicine, the IRB of record for the American Cancer Society and its Malawian partner, the Centre of Agricultural Research and Development.

To estimate the farmers’ gross margins, which are tobacco-related revenues less total tobacco-related costs, the survey explored the money earned by selling tobacco and the details of all costs associated with growing tobacco, including all inputs, fees, penalties and importantly, labour. The survey asked respondents to identify all of the various activities that occur in leaf production. For each activity, respondents indicated how many people from the household were involved, the total number of days that each household member worked on the activity, and how many hours per day on average each member of the household worked on the activity. The total number of hours for all household members for each activity was calculated based on responses. All monetary values are presented in both Malawian kwacha (MWK) and US dollars (USD). The conversion rate at the time of the survey was USD1=MWK394. The national rural minimum wage rate for the 2013/14 season was MWK 69/Hour (US$0.18/Hour) and was used to calculate the cost of the household labour. The finding that hired labour consisted of a wide variety of individuals suggests that household members could find employment on other farms (i.e. this suggests broader employability). In addition to family labour, respondents were also asked if they used any hired labour, though this cost was included in the calculation of total input costs for each activity, not in the household labor calculation.

To determine the sample size of the survey, we first defined the population size N of tobacco farmers in Malawi to be approximately 600,000. For the simple random sampling process, we adopted the conservative standard deviation p̂ to be 0.5, confidence level as 95% (Z=1.96), and we allowed the margin of error e to be 4%.

| (1) |

The equation (1) indicated that the unadjusted sample size needed to be 625. To adjust for population size, equation (2) should be considered (n2 is sample size adjusted for population).

| (2) |

As the population size is large, the adjusted sample size remains at 625. Based on previous agricultural surveys in the country, we expected the response rate to be between 85% and 90% and sought to reach out to 720 tobacco farmers with a final sample size of 685 (~95.1% response rate). While we had no a priori reason to suspect that there were large regional differences, we nonetheless chose to implement the survey relatively evenly across the six highest tobacco-producing districts.

We drew from our focus group discussions (FGDs) to contextualize the survey results and to inform our multivariate analyses of the dynamics around the economics of tobacco farming. Overall, we conducted FGDs in four of the six districts (Rumphi, Kasungu, Dowa and Lilongwe). We randomly selected from one of the two TAs in which we had implemented the survey. The FGDs took place at the local Ministry of Agriculture office (called Extension Planning Area (EPA) office) in the selected TA. Participants were randomly drawn from the villages surrounding the EPA from lists of tobacco farmers provided by the EPA staff (n=10–15 farmers per FGD).

The initial choice of variables to include was influenced by earlier studies on determinants of agricultural technology adoption among smallholder farmers of groundnuts and/or maize in Malawi (22,23); and research on growing pigeonpea in Tanzania (24). The FGDs affirmed the relevance of many of these findings and identified other key explanatory variables of interest. Broadly, these variables include age, educational level, gender, marital status of the household head, land size, legal entitlement of the land, access to credit and the sources of livelihood.

A logistic regression was used to examine farmers’ decisions to sign contracts with tobacco leaf-buying companies, with the dichotomous “Contract farmer” as the dependent variable. We used the main variables above as the independent variables, while controlling for geographical district (with Rumphi as the baseline).

To complement the theoretically- and field-driven model, we also employed a machine-learning method, Random Forest (RF), which helps with variable selection and model improvement (see Supplemental File). After RF identified variables, we revisited our theoretical framework informed by the FGDs to consider which variables might have been overlooked. RF belongs to the decision tree family (25) which consists of many decision trees and outputs the class that is the mode of the classes output by individual trees (26). RF is helpful as a complementary analysis tool for logistic regression model, because it handles a considerable number of input variables without variable deletion, ranks the importance of explanatory variables and its recursive partitioning process brings in new perspectives in terms of exploring the feature space (27–29). The analysis was conducted in R version 3.2.2. Seventy percent of data were randomly selected and two hundred trees were constructed for fitting the forest model. The random seed 123 was adopted for the process; 65 potentially meaningful variables were included in the analysis and RF results ranked the top 30. The most influential variables are those with the highest %Inc MSE scores.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The sample of 685 farmers comprises a relatively equal distribution of contract (n=307) and independent (n=378) farmers from the six major tobacco-growing districts. Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of contract farmers and independent farmers, including means for the continuous variables and percentages for the categorical variables. We conducted independent sample T-tests to determine whether there are differences in the means of relevant variables between the two groups. The significance level of the independent samples T-test of equal means is reported in the last column.

Table 1.

Household Characteristics of Tobacco Farmers

| Household Characteristics | Independent Farmer N= 378 |

Contract Farmer N= 307 |

Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender of Farmer: | |||

| Male | 87.6% | 93% | |

| Female | 12.4% | 7% | |

|

| |||

| Age of Household Head | 40 | 41 | 0.148 |

|

| |||

| Years of Education of Household Head | 7 | 8.1 | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Household Size | 6.3 | 7.2 | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Legal Entitlement of Land: | |||

| Freehold/Inherited | 97% | 97% | |

| Leasehold | 1% | 2% | |

| Other | 2% | 1% | |

|

| |||

| Land Size (Acres) | 6.2 | 9.5 | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Cultivated Land Size (Acres) | 4.7 | 6.6 | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Land Allocated to Tobacco (Acres) | 1.6 | 2.8 | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Years of Growing Tobacco | 11.9 | 12.4 | 0.452 |

Table 1 demonstrates some similarities between independent and contract farmers. However, Independent farmers have a smaller average total land size – 6.3 acres of which an average of 4.7 acres is cultivated land – in comparison to contract farmers who have an average land size of 9.5 acres of which 6.6 acres is cultivated land. Similarly, independent farmers allocated on average a smaller amount of land – 1.6 acres – to tobacco growing, compared to contract farmers at 2.8 acres. The difference between the variables was statistically significant.

Gross Margin Analysis

To illustrate the first key feature of the respondents’ gross margins, Table 2 presents the total cost of the major physical inputs for cultivating tobacco leaf.

Table 2.

Non-Labour Input Costs for Leaf Production/Per Acre in 2013/14 Season by Type of Farmer and Labour Hours and Labour Cost

| Input | INDEPENDENT | CONTRACT |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cost (USD)/Acre | Total Cost (USD)/Acre | |

| Seed | 8.7 | 9.2 |

| Watering cans | 11.2 | 7.8 |

| Herbicides | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Pesticides | 5.7 | 15.4 |

| Hoes | 15.5 | 12.7 |

| Fertilizer | 149.8 | 211.5 |

| Other costs | 63.9 | 67.7 |

| TOTAL INPUT COST | 256.2 | 326.4 |

| Cost of Household Labour (USD)/Acre | Cost of Household Labour (USD)/Acre | |

| Nursery preparation | 7.0 | 4.9 |

| Nursery Sowing | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Nursery fertilizer application | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Watering of nursery | 63.5 | 44.5 |

| Nursery chemical application | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Land preparation | 36.9 | 31.6 |

| Planting | 7.6 | 5.9 |

| Chemical application 1 | 1.4 | 2.9 |

| Fertilizer application 1 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Weeding | 19.2 | 15.6 |

| Drying shed preparation | 5.3 | 4.6 |

| Fertilizer application 2 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Banding | 18.5 | 15.8 |

| Chemical application 2 | 1.1 | 3.9 |

| Harvesting | 102.4 | 93.3 |

| Drying | 94.5 | 78.8 |

| Grading | 35.0 | 41.9 |

| Baling/Packaging | 4.8 | 5.8 |

| TOTAL LABOUR COST | 407.5 | 359.5 |

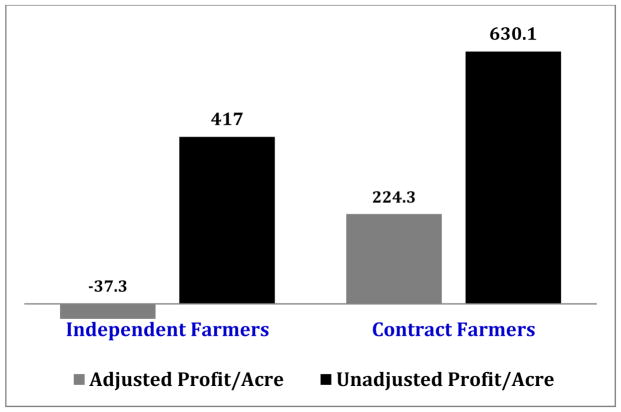

The differences between the two groups were statistically significant for fertilizer, pesticides and hessian sacks. Fertilizer costs make up about 58 percent of total non-labour production costs for independent farmers, and around 65 percent for contract farmers. In total, non-labour input costs per acre for contract farmers more than 27 percent greater than the total input cost per acre than independent farmers. The average cost of hired labour for the two types of farmers was similar: USD 46.8 for independent and USD 46.3 for contract farmers. The average profits per acre of the survey respondents (the total tobacco-related revenue less the total tobacco-related non-labour costs illustrated above) were USD 630.1 (contract farmers) and USD 417 (independent farmers).

To calculate the adjusted profits per acre for tobacco farming, the unpaid household labour costs were added to the input costs. Table 2 presents the costs of household labour for each activity in tobacco leaf production, based on the labour rates introduced above. The total labour cost per acre was 13.4 percent higher for independent farmers, USD 407.5 versus USD 359.5 (p<0.05). One quarter of labour is dedicated to leaf harvesting for both independent and contract farmers. Independent farmers have higher household labour costs per acre compared to contract farmers for most (14) farming activities except nursery chemical application, grading, and building and packaging.

Figure 1 presents farmers’ profitability, juxtaposing profitability without including labour with profitability that incorporates the basic costs of labour. With the labour inclusion, independent farmers’ profitability on average becomes negative, while contract farmers’ average profitability drops by nearly two-thirds to USD 224/acre.

Figure 1.

Profitability per Acre – Including Labour

Independent Farmers vs. Contract Farmers – Decision to Become A Contract Farmer

Table 3 presents the results of a logistic regression of the variables associated with a farmer’s decision to become a contract farmer. One of the most pronounced findings was the importance of improved access to credit. The coefficient is positive (1.79) and statistically significant. The educational level and age of the household head also have positive and statistically significant coefficients. Educational level has a positive coefficient of 0.070, which corresponds to an odds ratio of 1.072. The age of the household head has a coefficient of 0.021 corresponding to an odds ratio of 1.021. The dummy variable, Lilongwe district, has a negative and statistically significant coefficient of −1.121. Gender, household size, legal entitlement of land and tobacco revenue, and three of the district dummies, all have negative coefficients, but are not statistically significant. Similarly, land size and Mchinji district have positive coefficients but are also not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression of Decision to Contract Farm Tobacco Leaf

| Variable | Coefficient (S.E.) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 0.070** (0.032) | 1.072 | .0068293 .1332859 |

| Age | 0.021** (0.010) | 1.021 | .0014479 .0407494 |

| Gender | −0.369 (0.339) | 0.691 | −1.034214 .295791 |

| Marital Status | −0.293 (0189) | 0.746 | −.6641334 .0776689 |

| Household Size | −0.002 (0.039) | 0.998 | −.077806 .0747506 |

| Land size | 0.017 (0.013) | 1.018 | −.0089615 .0437512 |

| Legal Entitlement | −0.05 (0.538) | 0.952 | −1.103369 1.003958 |

| Kasungu District | −0.338 (0.325) | 0.713 | −.9741365 .2982531 |

| Mchinji District | 0.614 (0.354) | 1.848 | −.0788636 1.306963 |

| Ntichisi District | −0.293 (0.344) | 0.746 | −.9682023 .3815926 |

| Dowa District | −0.653 (0.352) | 0.520 | −1.34264 .036243 |

| Lilongwe District | −1.121*** (0.360) | 0.326 | −1.827255 −.4152208 |

| Need for Credit | 1.789*** (0.193) | 5.983 | 1.410803 2.166925 |

| Tobacco Harvested | 0.001*** (0.0001) | 1 | .0002846 .0008995 |

| Tobacco Revenue | −2.06e-07 (1.95e-07) | 1 | −5.89e-07 1.77e-07 |

| Years of Growing Tobacco | −0.019 (0.015) | 0.982 | −.0470926 .0100618 |

| Constant | −1.772** (0.850) | 0.170 | −3.438279 −.1055974 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Discussion

The survey results provide important insights into the economic livelihoods of tobacco farmers in Malawi, as well as similarities and differences between independent and contract farmers. In general, the demographic characteristics of the two groups of farmers are similar. Both are predominantly men, though contract farmers on average have larger land sizes and allocate slightly more land (~ 8%) to tobacco growing. The FGD participants suggested that leaf-buying companies sought out farmers with larger plots, perhaps for the sake of efficiency (i.e., contracting with fewer farmers). On average, 71 percent of contract farmers’ annual income comes from tobacco farming, which is 9 percent higher than independent farmers.

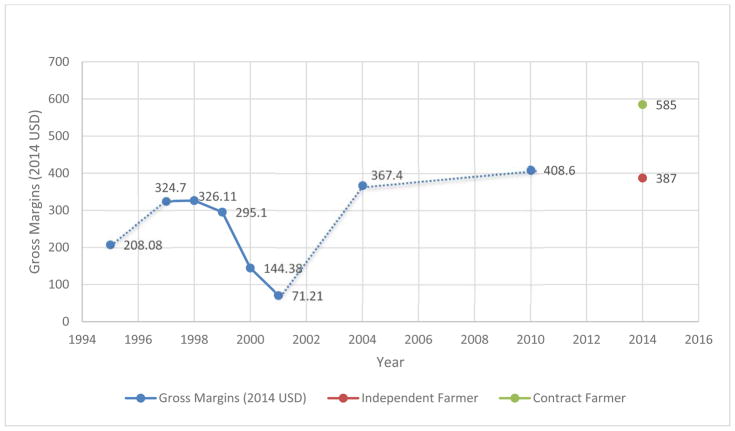

Figure 2 compares tobacco farmers’ gross margins in 2014 to previous seasons for which reliable data are available. The available data suggest historical volatility in earnings from tobacco growing, with 2014 appearing to be a relatively stronger year for contract farmers’ profits. The volatility is a function of both price fluctuations, largely due to changing global demand for specific types of leaf, and price volatility in the inputs market. For example, in the early 2000s, a worldwide spike in fertilizer prices negatively affected farmers’ margins (12), while in 2013–14, lower fertilizer prices – by far, tobacco cultivation’s largest input – benefitted farmers (30). Note that all of the studies we draw from in Figure 3 examine only gross margins, which is gross revenues less only the costs of the largest physical inputs (e.g. Fertilizer, seed and pesticide). Such an approach does not capture other expenses such as farming tools, levies and surcharges, and does not attempt to address issues around the value of labour. As well, the timing of large currency fluctuations has frequently affected tobacco farmers – negatively or positively – through price changes for selling tobacco and/or buying inputs, though these complexities are beyond this discussion’s purview (31).

Figure 2. Historical Gross Margins in Tobacco Cultivation – Malawi.

Sources: 1995 – Keyser and Lungu (1997); 1997–2002 – Jaffee (2003); 2004 & 2010 – Prowse & Moyer-Lee

The results from this study also identify several key differences between contract farmers and independent farmers. Results from the logistic regression demonstrate that farmers who had a need for credit have higher odds of becoming contract farmers than farmers who did not. This finding matches the results of the FGDs, in which farmers consistently raised the issue of credit, or lack thereof, and how contract farming can help to mitigate this persistent challenge. The high cost of fertilizer, an input without which leaf production in Malawi’s generally poor soils is hardly possible, is one of the key factors that attract farmers to enter into contracts with leaf-buying companies. The results also suggest that older farmers and farmers with higher education have higher odds of becoming a contract farmer. Notably, farmers living in Lilongwe district have lower odds of becoming contract farmers. Results of the FGDs suggest that these findings might be driven by better access to markets to sell other agricultural crops (e.g., beans and tomatoes) and/or other economic opportunities that permit these individuals to not need to rely on the ready credit of the leaf-buying companies.

Three intersecting factors help to explain the difference in the adjusted profit margins between the two categories of farmers: 1) non-labour inputs, 2) household labour costs, and 3) tobacco price at auction. The adjusted profit for contract farmers is roughly USD 300 per acre higher than independent farmers. However, the non-labour input costs were USD 70 higher than for independent farmers, notably for fertilizers and pesticides, which are supplied by the leaf-buying companies. The household labour costs were USD 48 higher for independent farmers. According to agricultural extension workers and some farmers in the FGDs, the additional household labour costs for independent farmers is likely a result of the additional labour required for weeding, the resultant banding (the physical weeding process can disturb the planting ridges, which must be addressed through banding), and all tasks associated with the nursery, harvesting and drying. The additional pesticides and herbicides provided to contract farmers likely result in less labour related to weeding and banding. In addition, the leaf-buying firms provide contract farmers with extension services that require a stricter schedule to tend to the nursery as well as the process of harvesting, which according to focus group participants may result in less labour costs for nursery tasks. This finding supports one of the rationale supporting the implementation of IPS, namely to increase efficiency and compliance in tobacco production (20). The cost analysis contributes to the literature by disaggregating contract and independent farmers as others have found that together small-holder farmers continue to face high production costs (32).

In the end, however, the main discrepancy between the adjusted profits for the two groups appears to result from different leaf prices. Put simply, it appears that contract farmers are being paid more for their leaf. There are many reasons why this practice may be occurring. It may be that contract farmers produce a higher quality tobacco leaf given the structured inputs and extension services. It may also be that contract farmers are given a higher price to incentivize the contractual relationship with leaf buying companies, a possibility that was raised repeatedly in the FGDs. It is possible that leaf prices are still being manipulated in Malawi similar to practices observed in the 2000s (13,21).

In any case, these findings suggest that when household labour costs are included, whether they are independent or contract, tobacco farmers are not earning enough to support a sustainable livelihood that is capable of meeting long-term personal or family economic needs. The average profit among all farmers is USD 79 per acre, which according to the Annual Economic Survey Report (2010–2011), is much less than the average income earned by those working in the agricultural sector (USD 351 in 2014 dollars). As another point of comparison, a 2013 study found that the average gross margins for a soybean farmer in 2013 was USD 644.19 per acre (33).

Moreover, if the labour costs of household members using the minimum rural wage level were factored into the prices paid by the tobacco-leaf companies and ultimately the tobacco transnational companies, it would equal USD 4/day (PPP1 ) for an 8-hour working day, substantially reducing the poverty levels of these households2 . By implication, the high profit margins of the tobacco transnationals (in 2011, 34 percent and 39 percent respectively for the two leading European firms, BAT and Imperial Tobacco) (34) whose enterprises are based entirely on the processing and sale of products made principally of tobacco leaf, are in part a function of the impoverishing unpaid labour of tobacco farmers’ households.

Limitations

One of the potential limitations of this study is in the calculation of household labour. We calculated household labour using the national rural minimum wage. The actual market-based labour wage may be higher in many circumstances than the national minimum wage. Additionally, the wage is highly variable between and within districts. Notably, these limitations suggest that the calculations in this research are likely an underestimate (i.e. smallholder tobacco farmers in Malawi are likely to be poorer than reported here).

A second limitation is that we do not capture the important dynamic around the thousands of tenant farmers on the large tobacco estates, for whom the research demonstrates gross exploitation by estate owners (35,36). Estate farming is a distinct and complex context that requires different methods than utilized in this research. A third limitation is that this research is only a snapshot in time. Farmers indicated that there have been better and worse seasons – often due to weather – and it is important that future research captures change over time.

Conclusion

This study finds that the pervading argument that tobacco farmers receive substantial economic benefits from tobacco production is overstated. We find that most smallholder tobacco farmers in Malawi make less than the average income in the country’s agriculture sector. This finding is the more striking when the unpaid household labour costs are calculated, which indirectly contribute to the high profit margins of tobacco transnational corporations. In sum, these findings strongly suggest that tobacco farmers in Malawi are not earning enough to escape extreme poverty, nor enough for their economic livelihoods to be used as a logical reason to oppose tobacco control. Even though Malawi is not a Party to the WHO FCTC, these findings should help inform ongoing discussions about livelihoods particularly in the context of Article 17 that compels governments to help find viable alternative livelihoods.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Tobacco interests often invoke tobacco farmer livelihoods to argue against tobacco control.

Quantitative analysis of the economic livelihoods of tobacco farmers is lacking.

This study provides one of the first cross-sectional studies of the economic livelihoods of a representative sample of smallholder tobacco farmers in Malawi, one of the major tobacco producing countries.

The results indicate that generally the economic costs of tobacco farming leave farmers with minimal profits or even with economic losses.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Fogarty International Center, and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA035158.

Footnotes

PPP (purchasing power parity) is an adjustment made by the World Bank converting a country’s national currency to make it equivalent to what that amount would purchase for a basket of goods in the US. For Malawi, the most recent conversion is 131.9 MKW = USD 1 (PPP). Source: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP

Although not eliminating poverty, since a recent assessment based on a 2006 study establish an ‘ethical poverty line’ of food, shelter, clothing and other forms of consumption required to achieve an average life expectancy of 70 years would, today, be USD 7.40 PPP. See: Edward P. The Ethical Poverty Line: a moral quantification of absolute poverty. Third World Quarterly 2006, 27(2), 377-393; and http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/nov/01/global-poverty-is-worse-than-you-think-could-you-live-on-190-a-day

Competing Interests: None declared.

Contributors DM, JD, FG, RZ, PM, RLen, RLab contributed to the study design. DM drafted the survey tool. JD, FG, RZ, PM, RLen, RLab contributed to subsequent refinement of the survey tool. DM collected the survey data. DM, RLen and PM contributed to the focus group design and data collection. DM, JD, AP and QL completed the statistical analysis. DM, JD, AP and RLen wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All team members contributed to the writing of the manuscript. JD led the revision. RLen submitted the manuscript on behalf of the team.

Contributor Information

Raphael Lencucha, Email: raphael.lencucha@mcgill.ca, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, 3630 Promenade Sir William Osler, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3G 1Y5.

Donald Makoka, Centre for Agricultural Research and Development, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Jeffrey Drope, Economic and Health Policy Research, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, United States.

Adriana Appau, School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

Ronald Labonte, Institute of Population Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

Qing Li, Economic and Health Policy Research, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, United States.

Fastone Goma, Faculty of Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

Richard Zulu, Faculty of Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

Peter Magati, Department of Economics, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

References

- 1.Warner KE, Fulton GA. Importance of tobacco to a country’s economy: an appraisal of the tobacco industry’s economic argument. Tob Control. 1995 Jun;4(2):180–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2012 Feb 28;23(1):117–29. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otanez MG, Mamudu HM, Glantz SA. Tobacco Companies’ Use of Developing Countries’ Economic Reliance on Tobacco to Lobby Against Global Tobacco Control: The Case of Malawi. Am J Public Health. 2009 Oct;99(10):1759–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, Bialous SA, Jackson RR. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2015 Mar 20;385(9972):1029–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckhardt J, Holden C, Callard CD. Tobacco control and the World Trade Organization: mapping member states’ positions after the framework convention on tobacco control. Tob Control. 2015 Nov 19; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052486. tobaccocontrol – 2015–052486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lencucha R, Drope J, Labonte R. Rhetoric and the law, or the law of rhetoric: How countries oppose novel tobacco control measures at the World Trade Organization. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Sep;164:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bialous S, da Costa e Silva V, Drope J, Lencucha R, McGrady B, Richter AP. The Political Economy of Tobacco Control in Brazil: Protecting Public Health in a Complex Policy Environment. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Centro de Estudos sobre Tabaco e Saúde, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública/FIOCRU; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chavez JJ, Drope J, Lencucha R, McGrady B. The Political Economy of Tobacco Control in the Philippines: Trade, Foreign Direct Investment and Taxation. Quezon City: Action for Economic Reform, American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drope J, Lencucha R. Evolving Norms at the Intersection of Health and Trade. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2014;39(3) doi: 10.1215/03616878-2682621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyser J, Lungu V. Malawi agriculture comparative advantage. Washington DC: World Bank; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Place F, Otsuka K. Tenure, agricultural investment, and productivity in the customary tenure sector in Malawi. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2001;50(1):77–99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaffee SM. Malawi’s Tobacco Sector: Standing on One Strong Leg is Better than on None. Afr Reg Work Pap Ser. 2003 Jun;(55) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prowse M. A comparative value chain analysis of burley tobacco in Malawi - 2003/4 and 2009/10. Institute of Development Policy and Management; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naher F, Efroymson D. Tobacco cultivation and poverty in Bangladesh: Issues and potential future directions. Dhaka: World Health Organization; 2007. (Ad Hoc Study Group on Alternative Crops) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kweyuh P. The economics of tobacco control: Towards an optimal policy mix. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town; 1998. Does tobacco growing pay? The case of Kenya; pp. 245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malawi tobacco earnings double to $361 mln. Reuters [Internet] 2013 Sep 10; [cited 2016 Feb 24]; Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/malawi-tobacco-idUSL5N0H62QQ20130910.

- 17.Leppan W, Lecours N, Buckles D. Tobacco control and tobacco farming: Separating myth from reality. Ottawa, ON: Anthem Press (IDRC); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.G/TBT/W/360. EUROPEAN UNION – TOBACCO PRODUCTS DIRECTIVE STATEMENT BY MALAWI TO THE COMMITTEE ON TECHNICAL BARRIERS TO TRADE AT ITS MEETING OF 6–7 MARCH 2013. WTO-TBT; 2013.

- 19.Makoka D, Munthali K, Drope J. Tobacco Control in Africa: People, Politics and Policies. London, UK: Anthem Press and IDRC; 2011. Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyer-Lee J, Prowse M. How Traceability is Restructuring Malawi’s Tobacco Industry. Dev Policy Rev. 2015 Mar 1;33(2):159–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otañez MG, Mamudu H, Glantz SA. Global leaf companies control the tobacco market in Malawi. Tob Control. 2007 Aug 1;16(4):261–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giné X, Yang D. Insurance, credit, and technology adoption: Field experimental evidencefrom Malawi. J Dev Econ. 2009 May;89(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simtowe F, Asfaw S, Diagne A, Shiferaw BA. Determinants of Agricultural Technology adoption: the case of improved groundnut varieties in Malawi. Cape Town, South Africa: 2010. p. 31. [cited 2016 Feb 28] Available from: http://oar.icrisat.org/5060/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiferaw BA, Kebede TA, You L. Technology adoption under seed access constraints and the economic impacts of improved pigeonpea varieties in Tanzania. Agric Econ. 2008 Nov 1;39(3):309–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach Learn. 2001 Oct;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2(3):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biau G. Analysis of a Random Forests Model. J Mach Learn Res. 2012 Apr;13(1):1063–95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biau G, Devroye L, Lugosi G. Consistency of Random Forests and Other Averaging Classifiers. J Mach Learn Res. 2008 Jun;9:2015–33. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strobl C, Malley J, Tutz G. An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychol Methods. 2009;14(4):323–48. doi: 10.1037/a0016973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Current world fertilizer trends and outlooks. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kandil M. The asymmetric effects of exchange rate fluctuations on output and prices: Evidence from developing countries. J Int Trade Econ Dev. 2008;17(2):257–96. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mkwara B, Marsh D. The Impact of Tobacco Policy Reforms on Smallholder Prices in Malawi. Dev Policy Rev. 2014 Jan 1;32(1):53–70. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makoka D, Kalengamaliro S. Mapping Exercise for soybeans in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: International Fund for Agricultural Development; 2013. (Rural Livelihoods and Economic Enhancement Programme) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilmore AB, Branston JR, Sweanor D. The case for OFSMOKE: how tobacco price regulation is needed to promote the health of markets, government revenue and the public. Tob Control. 2010 Oct 1;19(5):423–30. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CFSC. Tobacco Production and Tenancy Labor in Malawi: Treating Individuals and Families as Mere Instruments of Production. Lilongwe, Malawi: Center for Social Concern; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kafudu H. Review of the Working and Living Conditions of Tobacco Tenants and Other Workers on Tobacco Estates. Lilongwe, Malawi: Center for Social Concern; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.