Abstract

The prevention of intimate partner violence is a desirable individual and public health goal for society. The purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive assessment of adolescent risk factors for partner violence in order to inform the development of evidence-based prevention strategies. We utilize data from the Rochester Youth Development Study, a two decade long prospective study of a representative community sample of 1,000 participants that has extensive measures of adolescent characteristics, contexts, and behaviors that are potential precursors of partner violence. Using a developmental psychopathology framework, we assess self-reported partner violence perpetration in emerging adulthood (ages 20-22) and in adulthood (ages 29-30) utilizing the Conflict Tactics Scale. Our results indicate that risk factors for intimate partner violence span several developmental domains and are substantially similar for both genders. Internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors as well as early intimate relationships are especially salient for both genders. Additionally, cumulative risk across a number of developmental domains places adolescents at particularly high risk of perpetrating partner violence. Implications for prevention include extending existing prevention programs that focus on high risk groups with multiple risks for developmental disruption, as well as focusing on preventing or mitigating identified risk factors across both genders.

Keywords: Intimate Partner Violence, Risk Factors, Cumulative Risk

Introduction

The prevention of intimate partner violence (IPV) is a desirable individual and public health goal for society. Indeed, since 2008 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have identified the prevention of IPV as an important, but underachieved public health priority (CDC, 2008; O’Leary & Slep, 2012). The benefits of preventing IPV are evident when the scope and consequences of IPV are considered. A national surveillance system finds that almost one quarter of all American women and about 14% of men have been victims of severe physical IPV at some point in their lifetime (CDC, 2014). Reports from national surveys summarized by Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt & Kim (2012) suggest even higher rates with between 17% and 39% of adults experiencing partner violence in the past year. Both male and female victims suffer injury, although at somewhat different rates and levels of severity (Catalano, Smith, Snyder, & Rand, 2009; Dutton, Nicholls & Spidel, 2006). Moreover, both men and women victims suffer a range of health consequences, as well as emotional and behavioral problems (Coker et al., 2002). The impact of IPV exposure on children is also extensive and enduring (Ireland & Smith, 2009; McDonald, Jouriles, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano & Green, 2006). The purpose of this study, therefore, is to provide a comprehensive assessment of adolescent risk factors for IPV perpetration with the hope that our findings can contribute to the development of evidence-based strategies to reduce partner violence and its consequences through the prevention or mitigation of the identified risk factors.

Prevention science is “based on the premise that empirically verifiable precursors… predict the likelihood of undesired health outcomes” (Hawkins, Catalano, & Arthur, 2002, p. 951). Risk factor frameworks are central to the development of knowledge for prevention and are based on two core premises. First, there is no single pathway to negative outcomes and risk factors occur across multiple developmental domains or levels of a person’s social ecology (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; 1988). Second, it is typically the accumulation of risk that is most strongly related to adversity (Masten & Wright, 1998).

A prospective design is key to estimating risk effects within populations and such risk factors become the “best available targets for prevention programs presently” (Vagi et al., 2013 p. 634). Accordingly, we utilize data from the Rochester Youth Development Study, a two decade long prospective study of a representative community sample that has extensive measures of adolescent characteristics and behaviors that are potential risk factors for later IPV.

Conceptual Model

In order to select risk factors and domains that are believed to influence later IPV, we lean on the developmental psychopathology framework (Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000) which integrates developmental knowledge about adaptation and maladaptation across the life course (Coatsworth, 2010). In adolescence, a time of rapid transition and reorganization of a person’s contexts and interactions, successful development can be stalled by risks that emerge from multiple domains that may then powerfully impact the adult life course (Monahan et al., 2014) resulting in diverse behavioral and health problems (Coie et al., 1993; Masten and Cicchetti, 2010) including IPV.

A key idea influencing the current investigation includes the notion from developmental psychopathology, and from prevention and developmental science more generally, that development results from interactions between persons and their contexts at multiple levels (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1988; Kia-Keating et al., 2011). This leads to the importance of concepts of equifinality and multifinality. Equifinality refers to the notion that there not is a single dominant pathway to an outcome, for example, IPV, but multiple causes of and thus developmental pathways leading to that behavior that vary across individuals (Cicchetti and Rogosch, 1996). Multifinality, on the other hand, indicates that there are multiple outcomes from particular risk patterns (Coatsworth, 2010). Human development, viewed in this light, leads to a research approach that focuses on identifying the multiple precursors that, individually and in combination, lead to outcomes.

This perspective fits well with the investigation of IPV as several different theoretical perspectives have been offered to account for it. Social learning theory hypothesizes that children exposed to violence, both in the family and more broadly (e.g., at school and with peers), are at increased risk of later involvement in IPV. The developmental perspective (Capaldi, Kim, & Pears, 2009; Ehrensaft, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2004) suggests that earlier involvement in adolescent problem behaviors such as externalizing and internalizing problems, deviant peer relationships, school disengagement, and early dating has cascading effects from one developmental stage to another that lead to continued involvement in antisocial behaviors during adulthood, including IPV (O’Leary et al., 2014). Similarly, the interactionist model of human development (Conger & Donellan, 2007) emphasizes that children from families with low SES (including neighborhood and individual effects), highly stressed parents, and poor quality parent-child relationships fail to acquire the human and social capital necessary to form stable satisfying intimate relationships (Amato, Booth, Johnson, & Rogers, 2007; p. 3056) and are at an increased risk of involvement in IPV in adulthood.

In combination, these theoretical perspectives suggest that precursors for IPV come from a broad swath of earlier developmental risks – ranging from neighborhood characteristics and the SES of family of origin to individual characteristics like depression and hostile interactional styles. Unfortunately, there have been relatively few longitudinal studies of early risk factors for later IPV that have focused on equifinality and attempted to identify which of the broad array of potential risk factors are, in fact, significantly related to the outcome. The purpose of this study is to leverage the Rochester Youth Development Study’s longitudinal design and utilize the multiplicity of variables available to address this issue, focusing on both males and females. While no study is able to simultaneously examine all the developmental domains that have been hypothesized to be related to later IPV, the present study is able to examine many of them.

Domains of Risk for IPV Perpetration

We grouped the risk factors available in the Rochester study into 10 conceptual domains that reflect the learning, developmental, and interactionist models of development in order to provide a comprehensive assessment of which risk factors are significantly related to IPV during adulthood. To be consistent with our approach, we focus our review of previous studies primarily on adolescent risk factors, longitudinal studies, and those that measure IPV perpetration in adulthood, from 18 onward. Others (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2012; Renner & Whitney, 2012) have recently provided comprehensive reviews of the research on IPV risk factors that also include cross-sectional studies and investigations of teen dating violence.

Family-of-origin disadvantage

IPV is associated, albeit inconsistently, with disadvantaged socio-economic standing in the family of origin including both neighborhood/area characteristics and family background. Some have found that low income in the family-of-origin predicts later IPV (Giordano, Millhollin, Cernkovich, Pugh & Rudolph, 1999; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998) but others have not found significant relationships (e.g., Ehrensaft et al., 2004; Temcheff et al., 2008). An index of various family disadvantages including lower levels of maternal and paternal education, average family living standards ages 0-10, and socio-economic status at birth and at age 14 predicted later IPV (Fergusson, Boden & Horwood, 2008) and being raised in areas with high residential mobility and low responsiveness to neighborhood crime also predicted adult IPV (Herrenkohl, Kosterman, Mason & Hawkins, 2007). Overall, the pattern of results indicates that early family socioeconomic stressors and neighborhood disadvantage may contribute to later IPV, and there is no clear indication that risk in this domain is gender specific.

Parent stressors

Parent stressors, including problem behaviors, have been relatively unexplored. Maternal depression has been linked to violence perpetration in young adulthood for women, but not men (Keenan-Miller, Hammen, & Brennan, 2007). Retrospective measures of parental problem drinking, problem drug use (Roberts, McLaughlin, Conron, & Koenen, 2011) and parent antisocial behavior (e.g., Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Theobald & Farrington, 2012) predict adulthood IPV with no evidence of differential impact by child gender.

Parenting techniques

Poor parent-child relationships (Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Lussier, Farrington & Moffitt, 2009) as well as family conflict and corporal punishment (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Simons, Lin & Gordon, 1998; Woodward, Fergusson & Horwood, 2002) have been linked both to dating violence and adult IPV. However, other longitudinal studies that follow participants into adulthood find inconsistent associations, possibly because parenting is mediated by more proximal factors such as youth behavior (Capaldi et al., 2012). There is little clear evidence of gender differences, although Magdol and colleagues (1998) found that poor early parent-child relationships and family instability predict male, but not female IPV perpetration. In general, some aspects of parenting do predict IPV, although results are inconsistent about which aspect and whether or not the identified relationships are gender invariant.

Family violence

One of the most heavily studied risk factors for IPV is exposure to family violence as a child or adolescent, whether as a direct (child maltreatment) or indirect (exposure to parent IPV) victim. The prospective, intergenerational studies available report less consistent findings and weaker relationships than retrospective and cross-sectional studies (see Capaldi et al., 2012; Smith, Ireland, Park, Thornberry & Elwyn 2011). Witnessing violence between parents was predictive of IPV in several studies (e.g., Ireland & Smith, 2009; Linder & Collins, 2005). However, in studies that include IPV and maltreatment, maltreatment but not witnessing partner violence predicted young adult IPV (Linder & Collins, 2005). In all, evidence supports a modest but consistent connection between some aspects of family violence and IPV perpetration for both genders.

Adolescent stressors

Prospective studies do not consistently find that depression or anxiety during adolescence predict later IPV perpetration (e.g., Ehrensaft et al., 2004; Jaffee, Belsky, Harrington, Caspi & Moffitt., 2006; Keenan-Miller, Hammen & Brennan, 2007), but there is retrospective evidence that both women and men arrested for domestic violence offenses have histories of mental health conditions that include PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders (Stuart et al., 2006). Depressive symptoms do appear to predict IPV more consistently for women, compared to men (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; Renner & Whitney, 2012). Personalities characterized by negative emotionality also predicted IPV for men and women (Capaldi et al., 2012) as did suicidal ideation (Renner & Whitney, 2012).

Antisocial behaviors

A large literature links adolescent antisocial or externalizing behavior to subsequent IPV for both males and females. Several studies have found that adolescent antisocial behavior increases the risk of IPV in emerging adulthood (Andrews, Foster, Capaldi & Hops, 2000; Capaldi, Dishion, Stoolmiller & Yoerger, 2001; Magdol et al., 1998; Temcheff et al., 2008). Although there are some non-significant findings concerning antisocial behavior for females (Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, Fagan & Silva, 1997) and males (Kim, Laurent, Capaldi & Feingold, 2008; Renner & Whitney, 2012), longitudinal research is fairly consistent in finding that earlier antisocial behavior increases the risk for IPV perpetration for both genders. The role of other problem behaviors as predictors of IPV is less clear. Chen and White (2004) and Fergusson and colleagues (2008) found that adolescent problem drinking predicted perpetration of IPV in young adulthood for both genders and late adolescent drug use (but not alcohol use) did predict adult IPV perpetration for the males in the Cambridge study (Theobald & Farrington, 2012).

Delinquent peers

The role of adolescent peer groups is under-examined even though it “… is emerging as an important risk factor … for IPV” (Capaldi et al., 2012, p.29). Accordingly, Capaldi et al. (2001) found that deviant peer associations and hostile talk about women were related to subsequent male aggression toward a partner in emerging adulthood. Similarly, Lussier et al. (2009) found that having delinquent peers predicted male IPV in adulthood. However, we know virtually nothing about prediction for female perpetrators in terms of deviant peer group influences.

Early intimate relationships

Another important, but relatively underexplored, arena of risk that we can examine is early intimate relationships. Theoretically, the life-course perspective (Elder, 1998) emphasizes the importance of timing as people move along behavioral trajectories. Early or precocious transitions refer to a person taking on adult roles and behaviors prematurely making it difficult to develop normative competencies. This then creates turbulence and disorder in the life course that may increase the likelihood of adult behavior problems such as IPV (Carbon-Lopez & Miller, 2012; Krohn, Ward, Thornberry, Lizotte & Chu, 2011). Surprisingly though, there is very little literature that explores the early intimate relationships domain as a potential risk factor for IPV perpetration. An exception to this is early dating. Early first time dating has been associated with IPV perpetration (e.g, OLeary, Tintle, Bromet, 2014). Sexual risk behavior has been linked with IPV victimization among women in cross-sectional studies (e.g., Halpern, Spriggs, Martin & Kupper (2009). We could find no studies that considered precocious intimate relationships as risk factors for IPV perpetration in emerging adulthood or adulthood.

Educational experiences

Few longitudinal studies have examined the role of adolescent school achievement and other education-related variables in relation to adult, as opposed to adolescent, IPV. Low verbal IQ has been found to predict IPV among males (Lussier et al, 2009), although Woodward and colleagues (2002) did not find a significant relationship. Similarly, low educational attainment has been linked with IPV (Temcheff et al., 2008), although not consistently (Magdol et al., 1997). School dropout is independently related to various problem outcomes in young adulthood (Henry et al., 2012) but we could find no studies linking it prospectively to IPV.

Overview of the current study

The present study adds to the research literature and contributes to our understanding of the precursors of IPV in three important ways. First, consistent with the literature we investigated whether a broad range of risk factors, drawn from several interrelated developmental domains, were predictive of the likelihood of IPV perpetration. Few studies have simultaneously investigated risk in multiple domains, even though the probability of IPV may increase exponentially when risk is accumulated across several domains. Second, we examined IPV outcomes in two phases of adulthood to see whether adolescent risk factors continued to influence IPV beyond the turbulent period of early adulthood and endured into later periods when the life course is more settled. Third, we sought to shed further light on whether risk factors were common to males and females, or are gender-specific.

Methods

Sampling

The Rochester Youth Development Study (RYDS) is a multi-wave panel study that focuses on the origins and consequences of problem behaviors. Starting in 1988, it tracked an initial sample of 1,000 youth who were representative of all seventh and eighth graders from the Rochester, NY public schools, not just those who were already involved in problem behaviors or who had been arrested. A total of 14 waves of data, from ages 14 to 31, have been collected over three phases of data collection. Phase 1 covered the adolescent years from ages 14 to 18, when we interviewed the participants 9 times and their parents 8 times at 6-month intervals. In Phase 2, we interviewed the participants and their parents at 3 annual intervals, ages 21 to 23. In Phase 3, we interviewed the participants at ages 29 and 31. We also collected official data from the police, schools and social services. The original sample was composed of 68% African American, 17% Hispanic, and 15% white youth, consistent with the urban public school population from which it was drawn. To obtain a sufficient number of youth at high risk for various problem behaviors we oversampled males and also youth who lived in census tracts with high arrest rates. We included gender and neighborhood arrest rate in all analyses to account for this sampling technique. Attrition has been acceptable for a longitudinal study of this duration. At age 18, 88% of the adolescents and 79% of their parents were retained, as were 85% of the adolescents and 83% of their parents at age 23. Finally, at age 31, 80% of the initial adolescents were retained. Comparing the characteristics of respondents who were retained at age 31 to those who left the study demonstrate that attrition did not bias the sample (Bushway, Krohn, Lizotte, Phillips, & Schmidt, 2013). A more detailed description of the sample is found in the online supplemental information.

Measurement

IPV in emerging adulthood and in adulthood

IPV was measured with the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS, Straus, 1979). During emerging adulthood, at each of three annual interviews (ages 21 to 23), participants in married, cohabiting or long-term dating relationships (dating at least 6 months) were asked about the prevalence and frequency of each of 19 tactics employed during partner conflict within the last year. During adulthood, ages 29 and 30, they were asked the same questions at two annual interviews. Questions ranged from discussing issues calmly to using a weapon. We utilized the nine CTS physical aggression items that are typically combined to create a measure of the perpetration of physical violence. These include: 1) threw something at partner, 2) pushed, grabbed or shoved partner, 3) slapped partner, 4) kicked, bit or hit partner, 5) hit partner with something, 6) beat up partner, 7) choked partner, 8) threatened to use a weapon against partner, and 9) used a weapon on partner. We used binary measures of the prevalence of perpetration of IPV during both periods, coding 0 for no physical violence and 1 for any physical violence. We excluded from all analyses 47 participants who were not asked the CTS questions in either outcome phase since they were not married, cohabiting or in long-term dating relationships (dating at least 6 months). These excluded participants were not significantly different in regards to race, age, gender, or neighborhood arrest rate from the participants included.

Given the breadth of the measures used in this analysis, we present only a brief overview of risk factor measurement here. We provide detailed information on each of the 36 risk factors (e.g. standard deviation, range, alphas, and sources) in supplemental information available online.

Adolescent risk factors

Risk factors for IPV perpetration were split into ten domains that reflect important proximal and developmental contexts based on perspectives discussed earlier that include: area characteristics, family background/structure, parent stressors, exposure to family violence, parent-child relationships, education, peer relations, early intimate relationships, adolescent stressors, and adolescent antisocial/externalizing behaviors. The risk factors are all binary with 1 referring to the high risk end of the continuum. Those that were not originally binary were dichotomized at naturally occurring breakpoints (e.g., high school dropout, teen parent) or at the riskiest quartile of the distribution versus the lower three quartiles. Including all binary risk factors allowed us to compare the size and strength of the odds ratios across risk factors and binary variables were necessary for the cumulative risk calculation used in the analysis.

All risk factors were constructed so that they preceded the outcome. The early adulthood outcome was measured between ages 21 and 23 and the risk factor closest in time to the outcome is precocious parenting which was defined as becoming a parent prior to one’s 20th birthday. Cohabitation was defined as cohabiting prior to one’s 19th birthday. All other risk factors occurred earlier. The majority came from data collected at interview wave 7 or 8, when the respondents were on average 17 and 17.5 years of age. Many of the risk factors that refer to the family of origin – family poverty, parent’s depression and substance use, etc. – came from the earliest waves of the study when the respondent was on average 14 years of age.

Two indicators of area characteristics were used: percent in poverty in the participant’s census tract of residence and parent perception of neighborhood disorganization. Four indicators of family background and structure were included based on the parent report: low parent education, poverty-level income, teenage mother, and multiple family transitions. Four indicators of parent stressors included parent depressive symptoms, stress, marijuana use and alcohol use. Three indicators of exposure to family violence included a measure of substantiated maltreatment, parental partner conflict, and home hostility indicators. Parent-child relationship characteristics were measured with four scales utilizing parent and youth reporters, including low attachment to parent, low attachment to child, inconsistent discipline, and poor supervision.

The domain of education included four risk factors: low commitment to school, low college expectations, low parent college expectations for the adolescent and school dropout. The peer relationships domain had two self-reports by the adolescent – associating with delinquent peers and unsupervised time with friends. Measures of early intimate relationships included self-reported items denoting early sexual activity (before age 15), teen parenthood, and early cohabitation (living with a partner before age 19). Measures of adolescent stressors included four indicators: negative life events and two youth-reported standardized scales including depressive symptoms and low self-esteem, as well as internalizing problems from the parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The domain of antisocial behaviors included measures of delinquency, marijuana use, and alcohol use as reported by the adolescent, as well as the hostility and aggression subscales of the CBCL.

Analysis

We considered gender as a moderator variable and employed interaction terms, as recommended by Jaccard (2001), to test for significant moderator effects. Because significant differences between males and females were identified for only two of the 36 risk factors examined (see below), we present results for the full sample with gender as a control. In order to appropriately handle missing data we employed the Markov chain Monte Carlo method of multiple imputation in SAS, Version 9.2. Twenty imputed datasets were created, with imputations done separately for male and female subsamples prior to merging imputed datasets together to create one dataset for analysis (Allison, 2001). There is complete data for some of the variables (e.g. race and gender). For the variables with missing data, the range of missing values varies from 0.8% to 60.4% (median =18.6% and about 53% of the variables have less than 15% missing data). We only imputed data for those people who answered the CTS questions during either emerging adulthood or adulthood. Due to the binary nature of the dependent variable, logistic regression was employed in all analyses. A separate logistic regression model was run for each risk factor predicting IPV at emerging adulthood or adulthood.

To conduct the cumulative risk factor analysis, we determined the average number of risk factors within each domain for the full sample. Next, we calculated the number of risk factors each person had within each domain. Finally, we created a count of the number of domains each person had with above average risk. Using this cumulative count of domains with above average risk, we predicted IPV perpetration in both periods with logistic regression.

Results

In emerging adulthood, 56% of the participants reported that they perpetrated acts of intimate partner violence. At this developmental stage, females (74.6%) had higher rates than males (46.7%). The prevalence of IPV declined somewhat between emerging adulthood and adulthood; in adulthood, 31.6% of the participants reported involvement in IPV perpetration. Again, females (44.3%) had a higher rate than males (26.2%). This is consistent with other research using general community surveys that do not focus on clinically abusive relationships (Archer, 2000; Capaldi et al., 2012).

Risk Factors for IPV Perpetration in Emerging Adulthood

First, we examined adolescent risk factors for perpetrating IPV in emerging adulthood, about age 21-23 (Table 1, left column). All significant risk factors were in the hypothesized direction: participants in the high risk category had higher odds of violence. Of the ten domains, nine (all except area characteristics) had at least one significant risk factor suggesting that IPV risk factors span different areas of development. Exposure to family violence only had one significant risk factor, parental severe physical partner violence. This suggests some degree of intergenerational continuity in IPV; individuals exposed to parental violence are more apt to engage in IPV. The family background/structure, parent-child relationship, education, and adolescent stressor domains all had two significant risk factors. In the family background/structure domain, having a teenage mother and multiple family transitions significantly predicted IPV. In the parent-child relationship domain inconsistent discipline and poor supervision were significant predictors and negative life events and depressive symptoms were significant for the adolescent stressors domain. In the education domain, low college expectations and high school drop-out significantly predicted IPV. In the peer relationship domain, both associating with delinquent peers and spending unsupervised time with friends were significant predictors of IPV.

Table 1.

Relationship between risk and IPV in emerging adulthood and adulthood (N=953)

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio-Emerging Adulthood | Odds Ratio-Adulthood |

|---|---|---|

| Area characteristics | ||

| Percent in poverty | 1.08 | 1.04 |

| Neighborhood disorganization | 1.14 | 1.37 |

| Family background/structure | ||

| Low parent education | 1.47 | 1.32 |

| Poverty-level income | 1.21 | 1.73** |

| Teenage mother | 1.55* | 1.46 |

| Family transitions | 1.68** | 1.46 |

| Parent stressors | ||

| Parent depressive symptoms | 1.34 | 1.53 |

| Parental stress | 1.48 | 1.44 |

| Parent marijuana use | 2.61* | 0.80 |

| Parent alcohol use | 1.94** | 1.20 |

| Exposure to family violence | ||

| Parental partner conflict | 1.85** | 1.79 |

| Maltreatment victimization | 1.15 | 1.19 |

| Family hostility | 1.29 | 1.26 |

| Parent-child relationships | ||

| Low attachment to parent | 1.09 | .93 |

| Low attachment to child | 1.40 | 1.71* |

| Inconsistent discipline | 1.55* | 1.52 |

| Poor supervision | 1.75* | 1.13 |

| Education | ||

| Low commitment to school | 1.10 | 0.87 |

| Low college expectations | 1.62* | 1.17 |

| Low parent college expectations for adolescent | 1.49 | 1.21 |

| School drop-out | 1.66** | 1.47 |

| Peer relationships | ||

| Delinquent peers | 1.77** | 2.09*** |

| Unsupervised time with friends | 1.75** | 1.14 |

| Early Intimate Relationships | ||

| Precocious sexual activity | 1.93*** | 1.64* |

| Precocious parenthood | 1.42* | 1.13 |

| Precocious cohabitation | 1.74* | 1.59 |

| Adolescent stressors | ||

| Negative life events | 1.90** | 1.37 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.51* | 1.39* |

| Low self-esteem | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| Internalizing problems | 1.20 | 1.32 |

| Antisocial behaviors | ||

| General delinquency | 2.10*** | 1.85** |

| Problem marijuana use | 1.46 | 1.20 |

| Problem alcohol use | 1.63* | 1.32 |

| Hostility | 1.44 | 1.64 |

| Aggression | 1.67* | 1.89** |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

The domains with the largest number of significant risk factors were antisocial behaviors (with three significant risk factors) and early intimate behavior (all three risk factors were significant). For antisocial behaviors, general delinquency, problem alcohol use, and aggression were all significantly related to emerging adulthood IPV. The two risk factors with the greatest odds ratio were general delinquency (OR = 2.10; 95% CI 0.3, 1.1) and parent marijuana use (OR = 2.61; 95% CI 0.2, 1.7); for both of these, when the risk factor was present the odds of committing IPV during emerging adulthood increases substantially, more than doubling the odds.

Risk Factors for IPV Perpetration in Adulthood

For IPV perpetration during adulthood there were fewer significant relationships (Table 1, right column). This is not surprising given the longer temporal lag between the risk factors and the outcome. Nevertheless, in adulthood, six out of ten domains had at least one significant risk factor in the expected direction (compared to nine at emerging adulthood). In four domains there were no significant risk factors: area characteristics, parent stressors, exposure to family violence, and education. In the latter three, however, we identified significant risk factors for early adult IPV suggesting that there may be a cascade model at play from adolescent risk factors to early adult IPV and then to later adult IPV. This possibility is consistent with the findings of Smith et al. (2011). Five risk factors were significant predictors of IPV in both emerging adulthood and adulthood: delinquent peers, depression, general delinquency, aggression, and early sexual activity.

Although the pattern of significant differences for risk factors in emerging adulthood and in adulthood varied somewhat that did not mean that the odds ratios themselves are significantly different from one another. In fact, in all cases the pairs of odds ratios presented in Table 1 had confidence intervals that overlap, suggesting that they were not significantly different from one another, indicating that these adolescent risk factors were quite similar in their impact on the perpetration of IPV during emerging adulthood and adulthood.

Gender Differences in Risk Factors

Along with many in the field, we are interested in whether there are gender differences in the risk factors that significantly predict perpetration of partner violence and tested each risk factor for significant differences by gender using interaction terms. We did not tabulate these results since only two risk factors out of 36 significantly differed for males and females, and both were in emerging adulthood (results are available on request). The two risk factors in which we found gender differences were low attachment to child (OR = 1.75, 95% CI 0.05, 1.06 for males, OR= 0.66, 95% CI −1.2, 0.4 for females) and low college expectations (OR = 1.94, 95% CI 0.2, 1.1 for males; OR = 0.78, 95% CI −1, 0.5 for females). Given the number of interactions calculated it is quite possible that the two significant differences observed were generated by chance.

Cumulative Risk

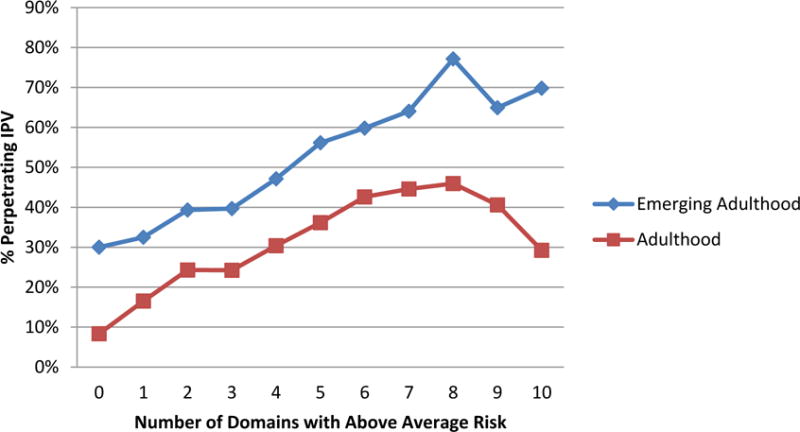

We turn now to the analysis exploring cumulative risk, or the effect of having above average risk across multiple developmental domains. We used a logistic regression model (including gender and arrest rate) to predict the impact of cumulative risk on IPV in emerging adulthood and in adulthood. With each additional risk domain that a person had, he/she was 1.25 times more likely to commit IPV in emerging adulthood and 1.18 times more likely to commit IPV in adulthood. Both results were significant at the p <.001 level.

Figure 1 illustrates this relationship: as the number of domains with above average risk increased the proportion of people who committed IPV generally increased in both periods. Although the curves tended to tail off at the highest levels of risk, probably because of somewhat small cell sizes, there was clearly a very strong positive relationship between cumulative risk and IPV perpetration. Specifically, in emerging adulthood, while only 27% of the group who had no domains with above average risk committed IPV, 72% of the people who had eight domains with above average risk committed IPV. This general trend was mirrored in adulthood, but the overall prevalence of IPV was much lower. In adulthood, the curve started with only 7% for those with no domains of above average risk exhibiting IPV and peaked at 45% of the sample, about 42 people, with above average risk in 7 or 8 domains committing IPV.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Risk for IPV Perpetration

Discussion

Intimate partner violence is a public health priority because of its negative and costly impact on adults, children, and society at large. In view of the equivocal effectiveness of intervening after violence has occurred, the current priority has shifted to prevention, utilizing science-based research (Dutton, 2012; O’Leary et al., 2014). We focus our discussion on the implications of our longitudinal findings for etiological research as well as the development of prevention programs, highlighting six areas: the multidomain nature of partner violence predictors, understudied risk factors and primary prevention, gender neutral programming and focus on women’s violence, cross-domain and cross-cutting secondary prevention programs, focus on high risk populations, and research on protective factors and pathways.

First, our findings support an etiology of partner violence that spans multiple domains of the developmental ecology. Looking across both outcome periods, several domains seem consistently important, including disadvantaged background, parent-child relationship problems, peer relationships, early intimate relationships, adolescent stressors, and antisocial behaviors. The first general implication for prevention science is thus affirming the multidomain nature of risk for partner violence and the complexity of overall risk for IPV. The role of equifinality and theoretical complexity derived from developmental psychopathology perspectives is supported. For example, social learning theory’s highlighting of family risk and violence is relevant to IPV outcomes, as are developmental frameworks that highlight early relationship risk and antisocial behaviors. IPV also may result from interactional perspectives that draw attention to early family disadvantage (Conger & Donnellan, 2007).

A second implication for prevention from these results is for primary prevention focusing on particular risk factors that may be markers for different pathways to IPV, such as early intimate relationships and delinquent peer relationships (Capaldi et al., 2012; Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012). In particular, early intimate relationships deserve further scrutiny: perhaps, as some research has suggested, these relationships are already marked by exploitation (Silverman et al., 2011). In any case, it would be fruitful to focus on sexually active and pregnant teens for IPV prevention (Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012). Teen depressed affect is under examined as an intervention target in relationship to a range of behaviors (Monahan et al, 2014) including IPV perpetration (Capaldi et al., 2012). It is notable that some risk factors come into play as age increases. For example, two risk factors have suppressed or ‘sleeper’ effects on later IPV only: low parent attachment and family of origin poverty. More research is needed to confirm or understand this finding and to track the role of risk markers and predictors over time and relationships in IPV research. Since there is commonality of risk factors across a number of outcomes other than IPV, as suggested by the concept of multifinality (e.g., Foshee et al., 2014; Monahan, Oesterle, Rhew, & Hawkins, 2014) it would be important to understand more about how and whether effects of risk as well as interventions can spread across domains and systems (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010).

The third implication for prevention derives from the finding that predictors of partner violence, at least among urban youth examined here, are overwhelmingly similar for male and female participants, as noted by others (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2008). Owing to the gendered nature of much prior research, less is known about women’s relationship violence, and thus this study adds important data to precursors for female IPV that may inform and broaden the scope of prevention research as well as programs. Prevention programs that are consistent with this multifaceted and gender-neutral understanding of the origins of IPV are thus important to emphasize (e.g., see reviews by Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi (2012) and O’Leary & Slep (2012)). On the other hand, we need to know more about young women who are violent and aggressive, and potentially show the poorest overall adjustment in violent dating relationships (Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012).

We also considered cumulative risk. Implications for prevention have a different emphasis here since “… the central point of the cumulative risk approach is that it is less important which individual risk factors are present or measured and more important to a population approach to attend to the overall load of risk …” (MacKenzie, Kotch, & Lee, 2011, p. 1640). Consistent with much that has been mentioned above, cumulative risk across a number of developmental domains places adolescents at higher risk than individual risks suggest (Appleyard, Egeland, Dulmen & Sroufe, 2006). Secondary prevention utilizing evidence-based programs that show efficacy among antisocial and multiple problem youth including Functional Family Therapy (Alexander & Robbins, 2011), Multisystemic Therapy (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland & Cunningham, 2009), and Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (Chamberlain, 2003) may also prevent IPV. Research on potential cross-cutting prevention strategies that currently focus on single risk behaviors can be extended to others such as IPV (Foshee et al., 2014). Targeting violence in intimate relationships as a component of such programs and tracking longer term partner violence outcomes would be a useful endeavor. Additionally, a profile of multiple risks including some of those suggested here may characterize youth caught up in service systems such as the juvenile justice, child welfare or mental health systems where there are missed opportunities for extending interventions to incorporate violence prevention in intimate relationships.

We did not focus in this study on protective factors, although this is an important emphasis of prevention science. However, our findings have implications for such research. For example, during emerging adulthood, 35% of the people with at least 9 domains of above average risk did not engage in partner violence; during adulthood, 59% of the people with at least 9 domains of above average risk did not commit IPV. A complementary research focus on developmental competencies and protective factors as well as reducing risk is emerging in the field of prevention in general (e.g., see Coatsworth, 2014; Kia-Keating et al., 2010) and that should extend to the investigation of partner violence.

The present study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. The most serious limitation in our data is lack of measurement of teen dating violence, a potentially important correlate of several behavior domains examined here, as well as a known predictor of adult IPV (Dutton, 2012; Vagi et al 2013; Cui, Gordon, Ueno, & Fincham, 2013; Renner & Whitney, 2012). Research has generally separated teen dating and adult IPV in view of the peak of violence amid more settled relationships that emerge in young adulthood (e.g., Capaldi, 2012). The relevance of this distinction can be examined by further research on early IPV pathways. Other limitations are reliance on a standard self-assessment of partner violence perpetration, the Conflict Tactics Scale. Although this is the most commonly used research measure of partner violence, critiques of it include potential overestimation of female violence and underestimation of male violence (Archer, 2000; Fergusson et al., 2008). We are also hindered by the use of a single informant for the measurement of some variables, notably partner violence itself. It should be noted that our results are specific to a particular cohort drawn from a single city and school district. Replicating these findings in other settings would certainly strengthen their generalizability.

Nevertheless the design and breadth of the current study does contribute to our understanding of the antecedents of partner violence and the potential for prevention. The results identified several important adolescent risk factors and potentially distinctive domains that are related to the later likelihood of partner violence. Future research should continue to focus on potentially distinctive developmental pathways that mediate the relationship between these risk factors and IPV. However, common risks among both males and females underscore the importance of more focused secondary prevention in high risk groups and among both genders. Cumulative risks and high risk loads go beyond individual risks to issues in families and environments that pile up to facilitate a trajectory of risk that overwhelms individual coping capacities and blunts appropriate system and community responses. Programs to address constellations of risk that put young people on the road to violent relationships can potentially increase their focus on this particular aspect of behavior in an effort to reduce the occurrence of IPV before it occurs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for the Rochester Youth Development Study has been provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R01CE001572), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2006-JW-BX-0074, 86-JN-CX-0007, 96-MU-FX-0014, 2004-MU-FX-0062), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA020195, R01DA005512), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH56486, R01MH63386). Work on this project was also aided by grants to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany from NICHD (P30HD32041) and NSF (SBR-9512290). We would like to thank the New York State Office of Children and Family Services for their assistance in collecting the Child Protective Services data. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander JF, Robbins MS. Functional family therapy. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing Data. Series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Vol. 139. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Booth A, Johnson DR, Rogers SJ. Alone together: How marriage in America is changing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi DM, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, Dulmen MH, Alan Sroufe L. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2005;46(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin. 2000;126(5):651. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Interacting systems in human development. Research paradigms: present and future. In: Bolger N, Caspi A, Downey G, Moorehouse M, editors. Persons in context: Developmental processes. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bushway SD, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Phillips MD, Schmidt NM. Are risky youth less protectable as they age? The dynamics of protection during adolescence and young adulthood. Justice Quarterly. 2013;30(1):84–116. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2011.592507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6(2):184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M, Yoerger K. Physical aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Pears KC. The association between partner violence and child maltreatment: A common conceptual framework. In: Whitaker DJ, Lutzker JR, editors. Preventing partner violence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez K, Miller J. Precocious role entry as a mediating factor in women’s methamphetamine use: Implications for life-course and pathways research. Criminology. 2012;50:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M. Bureau of Justice Statistics selected findings: Female victims of violence. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategic Direction for Intimate Partner Violence Prevention: Promoting Respectful, Nonviolent Intimate Partner Relationships through Individual, Community and Societal Change. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/IPV_Strategic_Direction_Full-Doc-a.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization - National Intimate Violence and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6308a1.htm?s_cid=ss6308a1_e. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain P. Treating chronic juvenile offenders: Advances made through the Oregon multidimensional treatment foster care model. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen PH, White HR. Gender Differences in Adolescent and Young Adult Predictors of Later Intimate Partner Violence A Prospective Study. Violence Against Women. 2004;10(11):1283–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8(4):597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Sroufe L. The past as prologue to the future: The times, they’ve been a-changin’. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(03):255–264. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth DJ. A Developmental Psychopathology and Resilience Perspective on 21st Century Competencies. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.hewlett.org/uploads/Developmental_Psychopathology_21st_Century_Competencies.pdf.

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, Long B. The science of prevention: a conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. American Psychologist. 1993;48(10):1013. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2002;24:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Ueno K, Gordon M, Fincham FD. The continuation of intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(2):300–313. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG. The prevention of intimate partner violence. Prevention Science. 2012:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG, Nicholls TL, Spidel A. Female perpetrators of intimate abuse. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2006;41(4):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A twenty year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–751. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspsi A. Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: Men’s and women’s participation and developmental antecedents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:258–270. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child development. 1998;69(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Developmental antecedents of interpartner violence in a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23(8):737–753. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes LM, Tharp AT, Chang LY, Ennett ST, Simon TR, Suchindran C. Shared longitudinal predictors of physical peer and dating violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Millhollin TJ, Cernkovich SA, Pugh MD, Rudolph JL. Delinquency, identity, and women’s involvement in relationship violence. Criminology. 1999;37:17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Spriggs AL, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Patterns of intimate partner violence victimization from adolescence to young adulthood in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW. Promoting science-based prevention in communities. Addictive behaviors. 2002;27(6):951–976. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CK, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic Therapy for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Knight KE, Thornberry TP. School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2012;41(2):156–166. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9665-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Mason WA, Hawkins JD. Youth trajectories and proximal characteristics of intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:259–274. doi: 10.1891/088667007780842793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland TO, Smith CA. Living in partner-violent families: Developmental links to antisocial behavior and relationship violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(3):323–339. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard JJ. Interaction Effects in Logistic Regression. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. (Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07-135). [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Belsky J, Harrington HL, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When parents have a history of conduct disorder: How is the caregiving environment affected? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(2):309–319. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan-Miller D, Hammen C, Brennan P. Adolescent psychosocial risk factors for severe intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2007;75(3):456. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kia-Keating M, Dowdy E, Morgan ML, Noam GG. Protecting and promoting: An integrative conceptual model for healthy development of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(3):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Laurent HK, Capaldi DM, Feingold A. Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-Year panel study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(5):1169–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Ward JT, Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ, Chu R. The cascading effects of adolescent gang involvement across the life course. Criminology. 2011;49(4):991–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Capaldi DM. Clearly we’ve only just begun: Developing effective prevention programs for intimate partner violence. Prevention Science. 2012:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JR, Collins WA. Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:252–262. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier P, Farrington DP, Moffitt TE. Is the antisocial child father of the abusive man? A 40 year prospective longitudinal study on the developmental antecedents of intimate partner violence. Criminology. 2009;47:741–780. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie M, Kotch J, Lee L. Toward a cumulative ecological risk model for the etiology of child maltreatment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1638–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(1):68. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and psychopathology. 2010;22(03):491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Wright MO. Cumulative risk and protection models of child maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma. 1998;2:7–30. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green CE. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(1):137. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan KC, Oesterle S, Rhew I, Hawkins JD. The relation between risk and protective factors for problem behaviors and depressive symptoms, antisocial behavior, and alcohol use in adolescence. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;42(5):621–638. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AMS. Prevention of partner violence by focusing on behaviors of both young males and females. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):329–339. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Tintle N, Bromet E. Risk factors for physical violence against partners in the US. Psychology of violence. 2014;4(1):65. doi: 10.1037/a0034537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner LM, Whitney SD. Risk factors for unidirectional and bidirectional intimate partner violence among young adults. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2012;36:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC. Adulthood stressors, history of childhood adversity, and risk of perpetration of intimate partner violence. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;40(2):128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, McCauley HL, Decker MR, Miller E, Reed E, Raj A. Coercive forms of sexual risk and associated violence perpetrated by male partners of female adolescents. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2011;43(1):60–65. doi: 10.1363/4306011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lin K, Gordon LC. Socialization in the family or origin and male dating violence: A prospective study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Ireland TOI, Park A, Thornberry T, Elwyn L. Intergenerational continuities and discontinuities in intimate partner violence: A two generational prospective study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:3720–3752. doi: 10.1177/0886260511403751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67(1):102. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temcheff CE, Serbin LA, Martin-Storey A, Stack DM, Hodgins S, Ledingham J, Schwartzman AE. Continuity and pathways from aggression in childhood to family violence in adulthood: A 30-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Theobald D, Farrington DP. Child and adolescent predictors of male intimate partner violence. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2012;53(12):1242–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagi KJ, Rothman EF, Latzman NE, Tharp AT, Hall DM, Breiding MJ. Beyond correlates: a review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2013;42(4):633–649. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(3):231–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1015150728887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.